Table of Contents

Introduction: Literary Past, Digital Present

Dr. Gideon Burton

Our present day feels like a storm of constant novelty, but we are actually repeating a parallel period of rapid societal change. Sure, our computers and media seem a quantum leap beyond whatever happened before, but this is not humanity’s first experience being reconfigured by a new medium, nor the first time western society has experienced widespread innovation and a flourishing of culture.

That prior period of amazing change and cultural development known as the European Renaissance is a lens on our own day. That is the pretext for this book. Collected here are 14 essays on contemporary issues in digital culture, each viewed through the historical lens of the Renaissance period and its literature.

As seen in the table of contents, we have grouped our essays under four heads: Digital Passports to Material Worlds; Building a More Creative Commons; the (De)Humanizing Web; and The Powers That Be Not. Threading through all of these are six themes from the historical Renaissance that we believe inform our present one. These have been our historical lenses upon our digital present:

Back to the Sources

One of the regenerative forces of the European Renaissance was the rediscovery of ancient Greek and Roman texts by humanist scholars like Petrarch. The old became new. History’s backlist was front loaded, fueled by the printing press’s hunger for new content.

The internet has exhumed the past en masse, giving billions access to the accumulated ideas and artifacts of the centuries. And as in the Renaissance, this delightful and daunting deluge of content has done more than produced more things to read and discuss; it is spurring us to return with new eyes and an experimental spirit to the material world. It turns out that the increased content and connectivity of the internet doesn’t trap people within electronic experience; it inspires them to go back to the physical sources of human activity with new perspectives and motivations.

Brave New worlds

Renaissance voyages of discovery traversed the world. Explorers found new continents, new resources, new dangers and new promises of riches and renewal. In similar fashion we cybernavigate our way to new kinds of works, ideas, and platforms that are as full of promise and threat as any wild island uncovered by a Columbus or Cortez.

Today we are awash in a wilderness of new things – new devices and access to media; new fields of action and domains of thought; new modes of human cooperation; even new modes of criminal activity. We are on par with those Renaissance-era explorers who sailed oceans and breached the brave new worlds that brought Europe both potatoes and syphilis; spices and slaves; colonies and calamities.

Figuring centrally among our brave new worlds are those social environments that appear to be an extension of the familiar, but which confound our morality and upset customary ways.

What a Piece of Work is Man

Our new media require us to rethink who we are – partly because (willingly or not) we have front row seats on other humans and their activities as never before. It isn’t the mass media or the intelligentsia that tell us who we are; we represent ourselves through text, image, and video in a neverending stream of profiles, selfies, and self-reflection. And we are increasingly convinced that our tools give us personal agency on a level unimagined before. The Renaissance was a period of similar self-revelation and also self-fashioning, full of posturing and progress in a more full display of human character(s) and what we are capable of. We are dazzled by our new views of who we are, alternately inspired and aghast at what we see and do online.

Plough Boys and Bibles

A major force animating change in the European Renaissance was the Protestant Reformation. We see in it a model for radical reform. As Luther stood up to the monolithic institution of Catholic Christianity, so today we see disruptive innovation, a ratification of the radical, similarly fueled by a democratic ideology. Anyone is an everyman, and everyone is their audience.

Our digital age is not experiencing a religious reformation, but the Protestant Reformation offers to today a potent pattern: the idea of access. Just as Bible translator John Tyndale sought to get God’s word into the hands of commoners like ploughboys, so the modern media reach out toward the masses. There is an egalitarian impulse that underlies the world wide web, a sense of entitlement regarding rights to participate, to seek and to say as one will. This right of engagement invites us toward collaboration, but it also warrants constant questioning of the powers that be.

The Printing Press

All of today’s changes are being fueled by the new medium. Just as print upset the Renaissance, forever reconfiguring the way the Western world thought, bought, and acted in society, so the internet and world wide web have begun a comparable radical reformatting of culture. It is an accelerant for change – especially on the social plane.

Sprezzatura and the Renaissance Man

A Renaissance courtly ideal confirmed the idea of a social self projected to others. People have always performed for one another in society, but today’s social media have created special conditions for culture today, as our virtual networks are present to us in ways that compete with flesh and blood physical presence. With social media come profiles and self-presentation, much in the way of posing. Ideals of behavior and performance circulate widely, and we are made aware of the accomplishments and experiences of others. The idea of a Renaissance man, a courtier well prepared and experienced, is being revived, in fact, if not in name, as we perform for others constantly in a fashion show of presenting our diverse, interesting selves.

Across the chapters of this ebook you will find these themes informing our understanding of today’s digital realities. Much is at risk as we redefine who we are while traveling together to brave new worlds. The European Renaissance took centuries to sort itself out and to leave to us its legacy. Perhaps the eRenaissance can be more smoothly navigated with the benefit of hindsight.

After all, one good renaissance deserves another.

About the Editor

Dr. Gideon Burton is Asst. Professor of English at Brigham Young Unviversity where he researches and teaches issues in digital culture and the rhetoric of online communication. He is the author of Silva Rhetoricae: The Forest of Rhetoric

Digital Passports to Material Worlds

In the age of the Internet, digital realities are now translatable to physical realities. A recent surge of how-to videos and DIY communities are enabling people to access resources and knowledge made available online, allowing their digital aspirations to become physical realities. Knowledge and skills that might have been lost in obscurity years ago are revivied and shared with a mouse click; virtual realities take physical, tangible shape; online chat rooms lead to lifelong friendships.

Commonly considered socially disengaging or detrimental to skill development, the internet is instead being used to physically experience what people have only ever seen online, and to allow for engagement in social and creative pursuits which were previously inaccessible. For those who lack the resources to physically do things themselves, they now find they are able to experience the authentic through proxy. In the following section we discuss the recent revival of traditions of the metallurgical arts, the spread of human survivalism, and the discovery of new worlds via digital tools.

Contemporary Crafts in a Digital Culture

Kurt Anderson

Modern Day Blacksmith

I watched a blacksmith pound red-hot, glowing iron in a rainy drizzle in England, and I was transfixed. I was studying abroad for two months in the spring of 2015, and we had come to the farm of Mary Arden, Shakespeare’s mother. Among the various Renaissance recreations of the farm was a forge, and at the forge was a man. His name is Thomas Beynon Timbrell, and he is a modern blacksmith.

After I watched him for a while, I struck up a conversation and learned much more than I had ever considered about the art of blacksmithing. And that is what it has become; an art. Previously, it was a pragmatic necessity, for soldiers needed armor and farmers needed plows, but today we use machines to create these items. The time and effort that it takes for a man to forge an axe versus the time and effort that it takes for a machine to forge an axe are practically not even comparable; what would take the smith weeks can be achieved in hours.

But there is something about the creation of beauty out of raw materials that is entrancing. And because of this, there has been a marked resurgence in modern crafting techniques. Take, for example, the Artist-Blacksmith’s Association of North America, or ABANA. They began in 1973 with twenty seven members, and have now grown to over four thousand members. In their mission statement, they state

“We understand that a blacksmith is one who shapes and forges iron with hammer and anvil. The artist-blacksmith does this so as to unite the functional with the aesthetic, realizing that the two are inseparable…We will preserve a meaningful bond with the past. We will serve the needs of the present, and we will forge a bridge to the future. Function and creativity is our purpose.”

The bonds of the past and the present are there, and the bridge between them may be found through the possibilities of a digital age.

Immaterial Vs. Material Satisfactions

Blacksmithing is just one of the various physically creative arts that are enjoying a boost in this digital age. Others include clothing and jewelry crafting, woodworking, and instrument building. However, in a world where you can simply go buy any of these object for a fraction of the cost and time, why would you want to create it yourself? An article by Suzanne Brown interviews Mark Montano, a sort of Do-It-Yourself guru who has broken away from the conventional fashion industry. He supports creating your own material things because he believes that “people need to feel a sense of accomplishment and not just press a button on the Internet.” In a sense, it is not the object that counts, it’s the making of the object that really makes us feel good.

In a modern world, how often can we actually enjoy seeing or touching a physical representation of our efforts? So many of our occupations are concerned with the immaterial, the transient information on the internet or through digitized data on computers, that it can be difficult to feel that satisfaction. If you are a banker, you no longer handle bags of golden coins. If you are a store owner, most of your merchandise will never pass through your own hands. In contrast, the creative arts such as textiles, forging, woodwork and stonework are hands-on and physically solid.

The concept of material creation bringing great satisfaction has featured in Utopian literature from the Renaissance. In Thomas More’s Utopia, he imagines a perfect society that lives on a large crescent island, undiscovered or tainted by man. He describes what their life is like, including their trades. He says, “Aside from agriculture (which, as I have said, is common to all), each person according to choice takes up a particular art, the manufacture of wool or flax, masonry, blacksmithing, or carpentry. And there are no other trades that are in great repute among them.” (More, 95) The only trades that these people engage in are those that directly create a physical product, not those that only create immaterial wealth. There are no bankers, traders, lawyers, or tax collectors. Also, it is because of choice and desire that these people engage in these creative activities, not to make money. There is no capitalistic economic system in Utopia; everyone works in the fields for food and then they simply provide each other with the things that they create. Because physical creation is satisfying, there is no need to charge for the final product. This viewpoint of physical creation for the sake of physical creation may be experiencing a great revival in our digital atmosphere, because we can use the immaterial connections that we have with others to get there.

Using the Immaterial to Achieve the Material

Ironically, it is generally only through the connections that we experience immaterially that these material arts have resurged. Since the ABANA has been established and was able to connect as a national group over electronical means, that is was has allowed them to flourish. Similarly, if I wanted to learn how to craft my own weapons or sew my own shirts, I would not have to necessarily seek out a blacksmith or a tailor myself, but rather I could learn how to do so from the Internet. The resources that allow us to return to the physical are not physical themselves.

Another issue is that of having the physical resources to create material products. I don’t happen to have a lot of iron lying around to forge with, nor do I have a forge, anvil, or hammers. However, it would be easier to do so now rather than before, since I could contact a seller of iron and forging tools via the Internet. Still, if I lack the time or possibility to do so, I can still experience some of the satisfaction of material creations by proxy. I haven’t actually crafted any swords, but I found that watching someone do so is almost as good.

Proxy Production

A video series of a man forging fictional weapons in real life, Man-at-Arms is a part of Awe Me on Youtube. It is a series which has garnered over twenty million views of the complete series. Taken separately, each of their videos has generally around one million views, with some at five to ten million. Three and a half million subscribe the channel, so the question is why is the idea of watching someone else hammer metal so attractive? I think that it is because it is a visible example of the previously only imagined becoming a physical reality.

The subjects of the videos can come from many different sources, such as television shows, anime, video games, computer games, and movies. As the popularity of a certain series or game grows, the blacksmiths will decide to forge one of the weapons a character uses or a piece of armor that a character wears. Popular examples include weapons from books, like Lord of the Rings, and games like Skyrim or Assassin’s Creed.

The enjoyment of these videos is the feeling of participation in the creation of something tangible. Although I am using the immaterial internet to view it, because I see the whole forging process from the point of view of the smith himself, I can feel like I am crafting something as well. Also, because the pieces that he creates are made from fictional sources, it adds a real sense of creations, something that had never before existed physically being pounded out on the anvil. As much as this may also be a certain form of escapism for those who are fans of these franchises, it is also a connection between real life people and fictional characters forged by the beat of a blacksmith’s hammer.

Time-honored Techniques

This rebirth of interest in the forging of weapons and armor may have appeared odd to someone from the Renaissance. After all, for them the blacksmith was a common part of everyday life. If you needed something made out of metal, you went to a blacksmith. Period. For hundreds of years prior to the Renaissance, there was no other option to get the work done. This elevated the blacksmith to a fairly high position in the Medieval village dynamic. As two contemporary metallurgists put it, “Blacksmiths and astronomers were among the elite occupations of ancient times because their work led to an understanding of the nature of earthly and extraterrestrial aspects of life.” (Wadsworth and Sherby) If you had no tools, how could you do your work? If you had no blacksmith, how could you have tools? The importance of the blacksmith did not dwindle significantly until the Industrial era, so the blacksmith was as essential to the Renaissance village as the internet is to a college dorm.

Even more interestingly, there were different levels of quality forging that blacksmiths aspired to. An example of this is Damascus steel, a hot topic among blacksmiths and metallurgists of today. Damascus steel, so named by Europeans because they first encountered it in the markets of Damascus, is a steel that is incredibly durable, sharp, and flexible. In fact, its quality is equal to that of the finest steels we can produce today. And the kicker? It was produced as anciently as 500 BC. Although at times we may believe that we have achieved technological heights never before seen through modern technologies like electricity and the Internet, in all reality there are many things we can still learn from techniques of the past, physical inheritances that we can discuss and share through digital means.

Continuing Discoveries

The rediscovery of these ancient techniques allows modern artists, scientists, and creators to synthesize new and innovative materials and techniques today. Recently, modern science has discovered that the secret to this steel lies in the nano-level carbon configurations in the steel atomic lattice. Scientists and metallurgist across the world are now trying to replicate the properties of Damascus steel to create ultra-strong wires. There is utility in the techniques of the past as well as the beauty of seeing the physical product of our physical efforts.

Tom Timbrell, the blacksmith who I met at the farm that day, explained to me what it is like to work as a blacksmith in a modern world. In regards to how modern technologies have affected his work, he said “I use the internet but rarely to connect with other blacksmiths,” explaining that to truly learn the craft one must meet with a Master Blacksmith. However, he also told me “When forging, if there is a technique I am struggling with, or can’t quite remember, I can find information that will refresh my memory via the internet. What is most useful today however, is the ability to look up an equation or heat treatment chart or even a data sheet for a particular metal in a matter of seconds due to mobile phone technology.”

When asked about the future of blacksmithing in the modern worlds, he was very optimistic.

I can very confidently say that blacksmithing is growing very healthily…many start it off as a hobby and teach themselves, eventually developing it into something more. The internet, with sites like Facebook, is connecting blacksmiths and in its way, does help many come into the craft via these interactions. It is, of course, only one side of the coin but it cannot be denied how useful for many the internet has been in getting involved with blacksmithing.”

Whether through blacksmithing, farming, or some other material creation, people of the digital age are finding new ways to work with the physical objects in their lives. As we pool our resources through the communities created through the Internet, we will be able to learn old techniques, create new ones, and feel the thrill of creating something physical again. Working through the immaterial, we will find a solid satisfaction in our different spheres.

Works Cited

ABANA, Mission Statement https://www.abana.org/ Web. Oct 26, 2015

Brown, Suzanne S. “DIY Guru : Creativity Results in Satisfaction.” Denver Post, sec. FEATURES: 1C. June 16 2012. Print http://www.lexisnexis. com/hottopics/lnacademic/?verb=sr&csi= 144565&sr=HEADLINE(DIY +guru%3A+Creativity+ results+in+satisfaction) %2BAND%2BDAT E%2BIS%2B2012

Man-at-Arms. Awe Me Media. https://www.youtube.com /user/AweMeChannel Web, 26 Oct 2015.

More, Thomas. Utopia, Library of Congress, Web. Oct 30, 2015 http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/thomas-jeffersons-library/interactives/sir-thomas-mores-utopia/

Sherby, Oleg D., and Jeffrey Wadsworth. “Ancient Blacksmiths, the Iron Age, Damascus Steels, and Modern Metallurgy.” Journal of Materials Processing Technology 117.3 (2001): 347-53. Print. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0924013601007944 Timbrell, Tom. Personal Interview. November 21, 2015.

Image Credits

- Tom Timbrell Portrait, © Rob Tranter Used by Permission https://www.facebook.com/bbblacksmithing/photos

- Kurt Anderson portrait @2015 Kurt Anderson

About the Author

Kurt Anderson is a Senior who feels like a Sophomore at Brigham Young University. He is an English major who is probably going to end up as an English professor. He lives in Provo, Utah for the foreseeable future.

From the InterWeb to the Bunker

Ahnasariah Larsen

A year and a half ago, Elaine Brickly got married - started a new life - and, almost at the same time, her father discovered the apocalypse. He read a book called Visions of Glory, by John Pontius. The book recounts a man’s apocalyptic vision at the time of a near death experience, and correlates closely with Biblical accounts of the End Times. EMP wipeouts, tent cities populated by the chosen elect, food storage, the destruction of specific cities, encounters with authorities beyond the grave: the book says it all. And for Elaine’s father, it convinced of all.

Almost overnight, Elaine’s father was a prepper.

Preppers, or Survivalists, believe that mankind has been effectually crippled by modern technology. Our lives have gone soft, they say. We don’t know how to survive anymore. When everything collapses – and they insist it will – our biggest killers will be starvation. Dehydration. The weather. And in extreme desperation, our neighbors (who might be zombies).

Said one YouTube prepper, “Many ‘survivalists’ are preparing [for] a global or regional chaos, and a lack of resources, while today’s world is totally dependent on a constant supply of various resources” (Cachet).

So they’re getting ready. The Preppers are stocking food, building bunkers, and arming themselves with everything from semi-automatic rifles to stone-age dart throwers. In extensive communities, they’re “brainstorming grid-down scenarios and strategizing to overcome obstacles therein” (Canadian Prepper). Elaine’s father bought two years’ worth of food storage, a small moving truck, and a ten-thousand dollar tent. He equipped each household member with three guns apiece: one long-range hunting rifle, one pistol, one shotgun. And he joined a paid-membership website, just for preppers.

But not all preppers are extremists. From Chicago, O’Connor declared, “the prepper movement has climbed out of the bunker and established itself, quietly, along affluent streets in Chicago, its suburbs, and beyond.” Once upon a time, the image of a prepper was that of a man far removed from civilization, unshaven and unwashed, a gunman, out to prove his self-reliance. That was last generation. The new generation of preppers encompass a wide spectrum of individuals, ranging from the urban to the rural, from the family who shelves a few extra pounds of rice against hard times to the father who buries a bunker and four years’ worth of food in his backyard. They’re our neighbors, teachers, cousins and - in Elaine’s case - our parents.

The Prepper Apocalypse

For the most part, Americans are not under immediate threat. Foreign terrorists haven’t caused anything close to a crisis since 2001. The last military attack on our shores, organized under a legal government, was December of 1941 - some 74 years ago. The economy is relatively stable; immunizations protect us from most epidemics; we rank 127th in poverty levels (meaning 126 countries have higher poverty than we do; and our percentage is hanging out at a fairly low 15%); we enjoy first world technology. We live in comparative comfort and security. For most of us - particularly those with the means to invest in a prepper’s lifestyle - there isn’t much cause for concern.

It begs an obvious question: why are we prepping?

A few, like Cat, began prepping after a personal experience. “A loss of income,” she says, “kicked our interests in preparedness, homesteading, and modern survivalism into high gear.” She’s one of the more moderate preppers, focusing on more realistic situations - like natural disasters, such as earthquakes or severe storms.

Some, like Jessica Bennett, point to an increased awareness of global peril as the cause. “A decade later, “preppers” are what you might call survivalism’s Third Wave: regular people with jobs and homes who are increasingly fearful about the future—their paranoia compounded by 24-hour cable news,” she writes. Her theory aligns with the prepper rhetoric: a big disaster is coming, civilization is going to collapse, and only the prepared will survive. Big disasters are what we see in the news now - earthquakes, civil wars, hurricanes and terrorists. It’s a bombardment of fear.

But there’s more to it than that.

The Magic of Digital Friendship

In the past decade, social communication has become almost synonymous with the internet. “In recent years,” wrote Richard Sherman in 2001, when the Internet was still wobbling on its first baby legs, “the Internet has greatly expanded the ways in which we communicate and interact with others. Email, instant messaging, chat rooms, newsgroups, listservs, world wide web home pages, and online interactive games are becoming important venues for developing and maintaining social relationships, and our perceptions in these contexts have increasing importance to our daily lives” (54).

That was fourteen years ago; when Sherman wrote of an emergent revolution in communication, I was seven and still eating my neighbor’s lilacs. Now, at twenty-one, I eat recipes from Pinterest.

Everyone I know communicates online. And that’s no exaggeration. I remember when MySpace was big (and then Facebook appeared, and overran everything). Heck, I inherited my sister’s old iPhone July of 2015 - my third smartphone in just as many months - and found half a dozen apps for social media sites, several of which I hadn’t even heard of. There’s Tumblr, Flicker, Snapchat - I can communicate with friends around the globe because online social media makes it happen.

All this communication means the formation of new, extensive communities. Just as I can chat, in real time, with friends in another hemisphere, there is the potential for meeting and befriending strangers from anywhere. I have, actually. Mostly with people I would never recognize in real life, because they used aliases and usernames and strange mashes of letters and numbers to identify themselves. I’ve participated in big communities like Facebook and Tumblr, and I’ve participated in smaller online communities for fandoms, artists, fantasy writing, photography, and more. There’s a community for every interest - including prepping.

So while news channels and terrifying apocalyptic books and brief encounters with hard times spark an interest in preparedness, massive digital networks feed the flame, encouraging and enabling us to take it a step further.

The Siren’s Song through a Megaphone

Let’s say I get an idea, something like: poetry should be about plants, not people. So I start writing poetry about plants, and I start telling friends about it. I say, “hey, guess what? The best poetry is about plants. You should write about plants instead.”

If that’s all I do - write poetry and talk to people - my poetry-plant movement isn’t going to get very far. My parents, my siblings, my friends, maybe a few cousins will know about it; of those people, maybe two are poets like I am; of those two poets, maybe one will try it out. So now there’s me and one other person writing poetry about plants. Big whoop-de-doo.

But if I can contact more people about it, find more poets and convince them to write about plants with me - why, then I’ve created an entire literary movement. And how? By networking. The power of networking is increased communication; the more people you can contact, the more individuals you can bring to your cause.

Martin Luther used that fact to take on a world power - and win.

By the time Luther was born in 1483, the Catholic church had been in power for roughly a thousand years. There was no such thing as not being Catholic. Every now and then dissenters rose from the ranks, solitary weeds in a rose garden, like John Wycliffe and William Sawtrey. Wycliffe translated the New Testament into English; Sawtrey, his follower, rejected the worship of Catholic saints.

He was burned.

Luther probably would have met a similar fate if it weren’t for a propitious invention. Late in the fifteenth century, a man named Gutenberg invented one of the most revolutionizing technologies in all of human history: the printing press. Said one scholar, the printing press “affected events as well as ideas and actually presided over the initial act of revolt.” (Eisenstein 306).

Luther recognized in the press its ability to communicate ideas to a wide audience. He began printing pamphlets and distributing them throughout the countryside, spreading his dogma of religious reform to the layfolk. Those who could read took the pamphlets to the marketplace and the dinner table, where they would read it aloud to an attentive audience (Waugh, Part Two). More and more people dissented, until even the German princes were on Luther’s side; and for the first time, a protestant movement was actually successful.

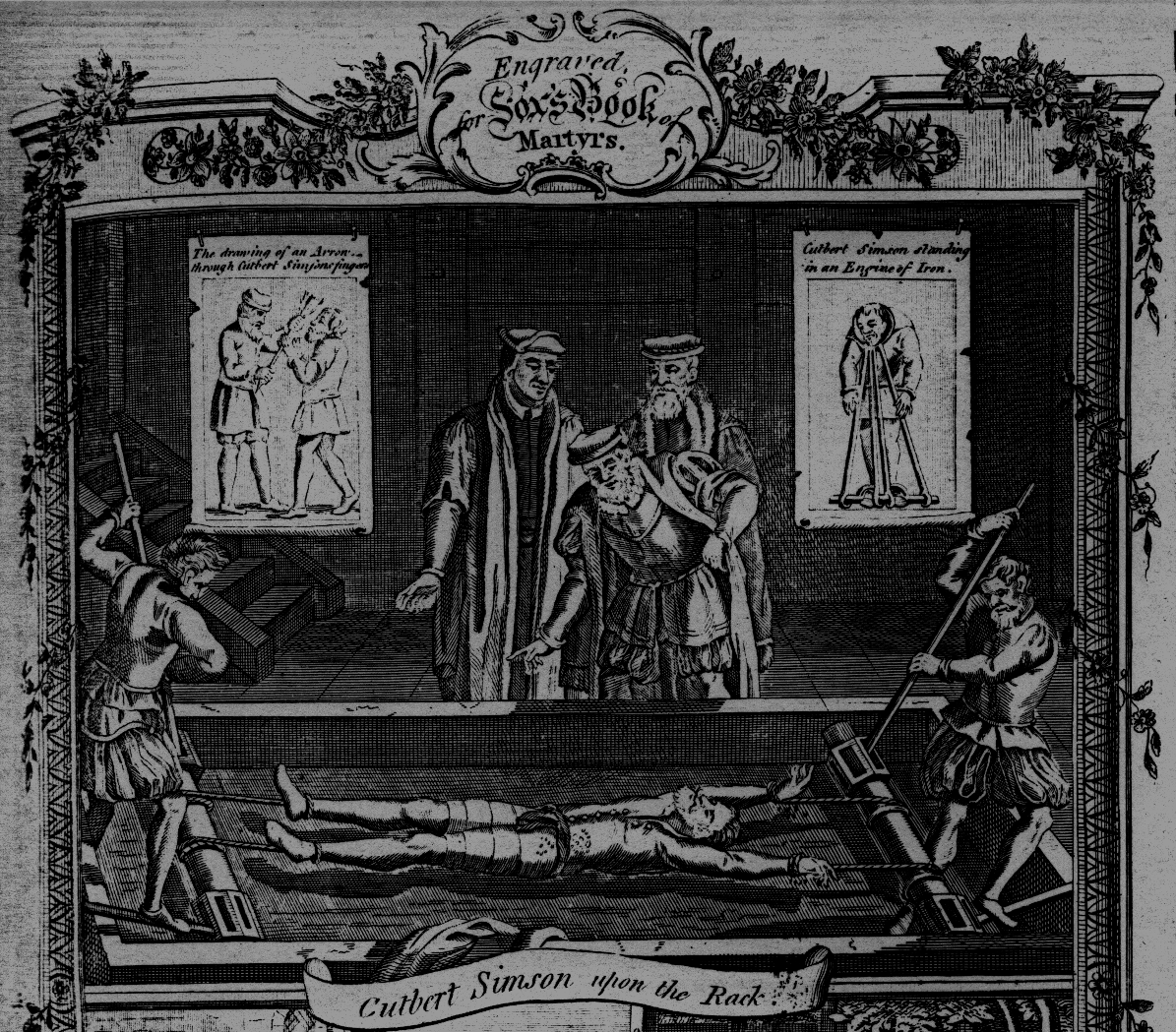

Luther wasn’t the only one who caught on to the power of the press. Around the same time, a book was published called The Acts and Monuments, by John Foxe. Today it’s known as Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. Foxe collected the histories of several religious martyrs, gathered them into a single book, and let it loose on the public.

Foxe’s book was hugely successful, but not because of what he wrote. “It can be generally stated that there were two types of printed materials,” notes Barry Waugh, “each of which targeted different segments of the culture. The first type of printed material was illustrated simple publications designed to reach those who could not read; the second type of publication was the text dense books and pamphlets for the literate.” (Waugh, Part One)

The Acts and Monuments included several woodcuts - you carve a picture in a block of wood, then use it like a stamp - of the martyrs and their deaths. The images were gruesome, violent, and blunt. Men burning at the stake. Men being tortured. Men being hung. “The Acts and Monuments was… illustrated on a scale and with a technical finesse unmatched in previous English printed books” (Evenden 1).

A lot of the martyrs Foxe depicted were his contemporaries, men the public knew. Seeing their deaths brought home a difficult and terrible truth to the people, pushing them further away from Catholicism and closer to Protestantism. The book had a huge influence in how people in England and other parts of Europe viewed the Catholic church - opinions that, nearly five hundred years later, still linger.

Four-Eyed Society: The Glasses We Wear

Sometimes, in today’s overly individualistic world, we underestimate the power of communities. Talk to anyone, any random stranger on the street, and you will probably hear the sentiment of, “I am not a sheep. I’m not dumb. I’m not someone who follows the crowd; I’m different.” And we often think that those who do adhere to culturally dictated practices have been somehow brainwashed.

Case in point: the Preppers. It’s far too easy for us to point and laugh at the extremes they’ll go to, like installing underground bunkers in the backyard, or growing poisonous plants in the garden, or buying a million and one guns to shoot those zombie neighbors with. I mean, really. What sort of psychedelic trip are they on?

Except, they’re not.

It’s not a case of living in a hallucination; Preppers aren’t insane. They, like the rest of us, are responding to the social groups they belong to. Digital communities attract and create certain kinds of people and certain kinds of behaviors. In other words: I become like the people I hang out with.

Said Sherman, “If we interpret a situation as calling for a certain kind of behavior, our actions will set the norms for others to behave in a similar way. Note that the other people are responding to what they perceive to be the norm governing the situation, not in their mind to our behavior.” (59).

In simple terms: we follow the example of our peers, often without even realizing it. We use their behavior to interpret and understand a situation or an unspoken expectation, like the need to whisper in a library; and then we change our behavior to match. We fit in; we relate; we merge ourselves with a social group and satisfy our human desire to belong.

Dancing to a Tune

But communities and social groups don’t just set standards for behavior within the group; they have a serious say in how we perceive the rest of the world, too. We learn to interpret the world in part from personal experience, but mostly from our community.

In childhood, adolescence, and early adulthood, we lay the foundation for our outlook on the world; that outlook is either reinforced or challenged by the social groups we associate with. A diversity of friends and associates keeps us moderate, and relatively well grounded. With the advent of digital communities, though, we become entrenched in niche communities that feed our interests and perspectives until they evolve into absolutes and obsessions.

Logic would say that the thousands of differing voices online would keep us more moderate, but it’s just the opposite; we’ve become more selective in what communities we participate in, and those carefully selected communities preach an equally selected and limited point of view.

Consider. In a forum for preppers, there are lots of arguments and baseline assumptions in favor of an impending apocalypse. Not one consideration for the contrary exists. A newcomer enters - out of curiosity, or because s/he is truly concerned about the possibility of a disaster or collapse. S/he gets involved in the community. And instead of the members considering the validity of their apocalyptic claim, they simply assume it - no one offers a counterpoint, because that’s how the social behavior has been defined - so it must be true - their enthusiasm sweeps you down the rabbit hole - and BAM, you’re a prepper.

Before the Reformation, in another example, everyone was Catholic. Every now and then dissenters popped up, but without the printing press and its mass-media, their dissensions fizzled out. Their voices went unheard by the main community; Catholicism went uncontested, and existed as an absolute. It wasn’t until Luther, Foxe, and other reformers used the press to build a strong public following that dissention was really feasible.

But the creation of opposing communities - Protestant versus Catholic - opened the way for a new problem: splinter groups.

The Problem of Many Siblings

So long as Catholicism was the world power, Europe enjoyed religious unity, a reality where everyone was on the same page. Life was ordered, organized, and stable. You went to mass, you said your prayers, your hero was the Pope. Simple.

Then the Reformation happened.

Protestantism opened the door not for the simple binary distinction between Catholic and not-Catholic, but for a multitude of churches, an entire rainbow of definition. Elizabeth Eisenstein put it this way:

”Sixteenth-century heresy and schism shattered Christendom so completely that even after religious warfare had ended, ecumenical movements led by men of good will could not put all the pieces together again. Not only were there too many splinter groups, separatists, and independent sects who regarded a central Church government as incompatible with true faith; but the main lines of cleavage had been extended across continents and carried overseas along with Bibles and breviaries.” (Eisenstein 312)

Lutherans. Calvinists. Anglican. Puritan. Jesuit. Each church professed a different doctrine, and it wasn’t long before they set to brawling. Their disagreements led to wars, severe persecution, emigration, and exile. The Puritans, for instance, fled the Anglican church twice: once to Holland, where they worried the Dutch would corrupt their youth; then to America, where hundreds died from starvation and disease (Delbanco).

Religious violence between Christians abated slowly, and martyrs date from as recently as the nineteenth century. Even now, we bicker and quarrel over countless points of doctrine; at times it’s hard to tell we lay claim to the same God. “Long after theology had ceased to provoke wars,” said Eisenstein, “Christians on both continents were separated from each other by invisible barriers that are still with us today.” (Eisenstein 312-313).

Lucidly Insane

Our ability to communicate widely, and find people around the world who share the same interests, is wonderful. It’s amazing. It’s opened the door for the revival of old skills, like blacksmithing and cooking; it creates awareness of global issues; it allows us to experience culture and humanity in an infinite number of ways. To some extent, we are more aware of each other than ever before.

But then we pick up social cues from the people we associate with; and we use those cues to guide our behavior. This is a subconscious process, and happens naturally - but it has a huge impact on our approach to life. The phenomenon extends to the digital communities we participate in online; this fosters cultures and social movements on a global scale. More often than not we find ourselves immersed in niche communities, with very specific and sometimes limited worldviews; when those worldviews are translated and materialized into the real world through our behavior, through our lifestyle and life choices, things happen. Good things, like learning new skills. Strange things, like prepper extremists and their backyard bunkers. Sometimes bad things, like prejudice.

Our physical world is evolving. Every day it becomes a more accurate reflection of our digital existence, making the line from the intangible to the real ever more direct. That line has the potential to either strengthen society, by extending and interconnecting communities, or splinter us into a thousand thousand factions. It’ll probably do both.

Works Cited

“About The Backwoods Resistance.” BackwoodsResistance. N.d. Web. 8 November 2015. http://backwoodsresistance.com/about-the-backwoods-resistance/

Canadian Prepper. “Description.” YouTube. 7 May 2014. Web. 8 November 2015. https://www.youtube.com/user/CanadianPrepper33/about

Cachet, Marie. A myth in survivalism: hunger. YouTube. 19 January 2015. Web. 8 November 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n16xfyPTfCM

Cat. “About Cat.” HerbalPrepper. Herbal Prepper. n.d. Web. 8 November 2015. http://www.herbalprepper.com/about/about-cat/

Brickly, Elaine, anonymized. Telephone Interview. 3 November 2015.

O’Connor, Rod. “These Suburban Preppers Are Ready for Anything.” Chicago. Chicago Magazine. 27 April 2015. Web. 14 October 2015. http://www.chicagomag.com/Chicago-Magazine/May-2015/Suburban-Survivalists/

Bennett, Jessica. “Rise of the Preppers: America’s New Survivalists.” Newsweek. Newsweek. 27 December 2009. Web. 14 October 2015. http://www.newsweek.com/rise-preppers-americas-new-survivalists-75537.

Delbanco, Andrew. “Puritanism.” The Reader’s Companion to American History. Eric Foner and John A. Garraty, Editors. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 1991. History.com. Web. 3 December 2015. http://www.history.com/topics/puritanism

Eisenstein, Elizabeth L. The Printing Press as an Agent of Change. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1980. Print.

Evenden, Elizabeth, and Freeman, Thomas S. Religion and the Book in Early Modern England: The Making of John Foxe’s ‘Book of Martyrs.’ Cambridge University Press, 2011. eBook. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=-73NjzqeVv4C&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&dq=Book+of+Martyrs&ots=aa8ZIYmnZU&sig=h72TgLOFCFqD_2Y5J1r2Cqj-IB8#v=onepage&q=Book%20of%20Martyrs&f=false

Jussim, Lee. “Social perception and social reality: A reflection-construction model.” Psychological Review 98:1 (1991): 54-73. Web. http://web.b. ebscohost.com/ehost /detail/detail?sid=a52d9468-b1f2-4bb6-8153-30e3c2242f0f %40sessionmgr113&vid=0&hid=124&bdata =JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3 QtbGl2ZSZzY29wZT1 zaXRl#db=pdh &AN=1991-12530-001

“Population below Poverty Line.” indexmundi. 1 January 2014. Web. 9 November 2015. http://www.indexmundi.com/g/r.aspx?v=69

Sherman, Richard C. “The Mind’s Eye in Cyberspace: Online Perceptions of Self and Others.” Towards Cyberpsychology: Mind, Cognition, and Society in the Internet Age. Ed. G. Rive and C. Galimberti. IOS Press, 2001. 53-70. Web. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=c9UnQ0OKL_wC&oi=fnd&pg=PA53&dq=forum+self-confirmation&ots=MIcTDOqjnp&sig=n8WJMNdO4-i7GpyNytWNfnCmZSY#v=onepage&q&f=false

Waugh, Barry. “The Importance of the Printing Press for the Protestant Reformation, Part Two.” Reformation 21. Alliance of Confessing Evangelicals. October 2013. Web. 8 November 2015. http://www.reformation21.org/articles/the-importance-of-the-printing-press-for-the-protestant-reformation-part-two.php

—. “The Importance of the Printing Press for the Protestant Reformation, Part One.” Reformation 21. Alliance of Confessing Evangelicals. October 2013. Web. 8 November 2015. http://www.reformation21.org/articles/the-importance-of-the-printing.php

Image Credits

- Graphic by Chris Potter, stockmonkey’s.com. / CC BY

- Martyr by John Foxe, Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. 1563.

About the Author

Addicted to reading and storytelling alike from a young age, Ahnasariah Larsen enjoys a thriving love affair with all things literature. She spent her adolescence in Minnesota and considers herself a native, lives for a good thunderstorm, and is absolutely convinced that true happiness lies in a hot shower.

Responsible Wanderlust

Nikkita Walker

Knapsack Skills

I travelled by myself for the first time when I was twenty years old. I remember standing in the Suvarnabhumi Airport with my absurdly overweight backpack, looking outside at the pouring rain with newly exchanged baht in my hand and wondering how I was possibly going to handle Thailand. I didn’t speak any Thai, didn’t know that a cab would cost 400 THB when I could easily take the metro downstairs for 30 THB, didn’t know that even though it was late I could still find stalls open selling steaming, heaping plates of pad see ew or bowls of khao soi. I had bought the backpacker’s bible, Lonely Planet, and from everything I’d read on blogs I decided that the best place to start my trip would be Khao San Road, the tourist mecca folded into the older part of Bangkok, tucked between temples and palaces. Over time I abandoned the travel guide almost completely and started to rely on ex-pat blogs, recommendations from Thai friends, or responses on the ThornTree Forum. I stopped paying American rates for hotels and instead found myself getting tips from the girls in my hostel dorm, and then eventually started staying with Thai families that friends introduced me to. I learned how to use rome2rio.com to get between cities and that renting rooms on airbnb.com was cheaper than hostelworld.com but safer than couchsurfing.com. I never did get to relax on a resort beach, but by the end of my trip I knew how to order food and the fastest way to get around a city at rush hour. I shared breakfast on Mother’s day with a group of kathoeys (lady-men) and was adopted by the Hmong family I stayed with through a hug plix. That same summer my stepdad stayed in a Hilton down south in Phuket. For two glorious weeks he ate shrimp cocktails and lounged on a beach where elephants charged the surf. Now, more than two years later, he can’t tell me anything more about it than the bad shrimp, the white hotel room, and the elephants on the beach.

Today, there is a massive community of travellers communicating online in order to share tips and advice to enable others to experience a country as authentically as possible. Internet resources empower people to navigate foreign, physical worlds for themselves rather than blindly and faithfully relying on tour services to mediate foreign environments for them. The idea is not to take a vacation, not to take a break from the world, but rather to experience it as immersively and authentically as possible. The travel mantra of the modern digital age goes as follows: the journey is the adventure.

Renaissance Backpackers

Travel narratives serve as an inspiration, like a call to adventure, a beckoning to experience life beyond the patterns of the familiar. During the Renaissance, travel literature became popular after the surge of colonization and the advent of the printing press, which increased the literate population and the availability of reading material. The accounts of recent excursions from adventurers like Montaigne and Columbus acted like a red herring, drawing the European gaze outward, across the Atlantic or beyond the Mediterranean.

It was travel literature written in the style of artists-philosophers like Petrarch, which glorified the change and internal growth of self learned from travel, that motivated readers to consume the travel accounts of John Smith, Cabeza de Vaca, and Vespucci. Any hardships read about in these accounts were a part of the adventure, an uncomfortable difficulty but endurable and a part of the novelty of travelling. In a letter Petrarch wrote describing his ascent of Mont Ventoux he spends most of his account of the hike detailing the hardships he and his brother faced. Despite his frustration and exhaustion, and of course because Petrarch could not stop being a philosopher even when grumbling about all the prickly bushes, he reflects on how his journey is representative of his inner self. Despite the locals that advised him against the trip, Petrarch felt even more determined to accomplish the journey, and he remarks that “while he [a local shepherd] was shouting these words at us, our desire increased just because of his warnings; for young people’s minds do not give credence to advisers”(Petrarch 38).”

Petrarch relishes in the struggle, and his determination is proof to him of the strength of his iron will; he believes that traveling is something that only those with a fervent passion can truly and authentically experience. You cannot “merely want; you have a longing unless you are decieving yourself in this respect as in so many others. What is it, then, that keeps you back?”(Petrarch 40). Removed from society he feels free enough to breathe and fully understand himself without the buzzing interference of external interruptions. And of course, the view when he finally reaches the peak of Mont Venoux makes the struggle all worthwile: “I stood there almost benumbed, overwhelmed by a gale such as I had never felt before and by the unusually open and wide view”(Petrarch 41). Literary scholar Nathalie Hester argues that Petrarch is the original “noble traveler,” a “wandering poet” who “writes while navigating the river Po, who despises sea travel, longs for otium, but continues to wander”(Hester 129), and that Petrarch’s influential writing during the Renaissance created a style imitated by other writers in pursuit of “truth” and “authenticity” as Petrarch had been.

Petrarch’s narrative focuses on the spiritual change evoked by travel, John Smith’s narrative of his “adventures” around New England include more detailed accounts of the landscape and the mechanics of survival. Smith writes that “this coast is all mountainous and Iles of huge Rocks but ouergrowen with all sortsd of excellent good woodes for building houses, boats, barks or shippes; with an incredible abundance of most sorts of fish much fowle, and sundry sorts of good fruites for mans vse”(Smith 23), enticing other travelers to journey to the Americas. Smith’s hardships are similar to Petrarch’s: glorious. Only by negotiating with “terrifying” Natives or navigating the rocky landscape are people truly experiencing the Americas, these struggles are as much a part of the journey as is enjoying the beauty of the land. Where Petrarch was seen as the “noble wanderer” Captain John Smith reigned in the social consciousness as “stalwart adventurer.” Petrarch travelled in pursuit of self-awareness, Smith travelled in pursuit of a new experience, both boasted of their discovery of the authentic. During today’s digital renaissance, the reading population has access to a much larger body of travel literature and information than those during the earlier Renaissance, and yet the pursuit of the authentic remains the same.

“Admirable” Adventures and Endeavors

Anthropologist Daniel Carey hypothesizes that the entire field of anthropological study derived from the observation that travel has been considered a factor of changing identity for years. That, in interacting with different cultures in foreign environments, in many ways travel has been undertaken mainly with “the return” in mind, when the world-weary traveler comes back from their adventures a changed person(Carey 108). The greater the adventure, the more magnificent the return, and what was possible for a fearless few in proto-internet days is now available for anyone with a will and a familiarity with the right websites.

Because of the accessibility of adventure, there exists a subtle requirement that travel must be undertaken, and undertaken the right way, to prove individual authenticity. In a recent article published in The Atlantic travel writer Amanda Machado writes that there’s a rapidly growing percentage of “young travelers [who] are not as interested in “the traditional sun, sea and sand holidays” as previous generations are. They are spending less time in “major gateway cities” and instead exploring more remote destinations”(Machado). This desire to travel, and moreover to discover the road least travelled, is representative of what literary scholar Tom van Nuenen dubs “existential authenticity,” that this rising community of “authentic” travelers “are arguing that their journeys accommodate a state in which one can be true to oneself, contrary to the frustrating limitations of their former lives in Western society”(Nuenen 2). Like Petrarch wrote five hundred years earlier, this new community of travelers journey with the belief that the harder the trip the more authentic, and the more authentic the closer they come to understanding and declaring themselves. Nuenen writes that the very word “authentic” is the greatest appeal to travel today, that “its allure remains, an anchor point in the language of tourism, used in advertisements and travel writing alike”(Nuenen 2).

Authentic travel, like a right of passage, is something that needs to be undertaken on the power of the individual. At eighteen, just out of high school, my parents made me an offer. Pick a place, they said, anywhere you want. Where would you like to go? After literally being offered the world, I started researching through the Lonely Planet website - just a superficial Google search quickly revealed that Lonely Planet was the travel authority - and found a two-week tour that promised an adventure through Peru, complete with a village homestay and a four-day hike to Machu Picchu. I arrived and spent the trip in the company of a group of rowdy Australians who had been traveling months longer than I had. Do your research, they told me, don’t let other people decide your trip for you.

Millions of travel blogs across the internet ring with this same “call to adventure,” emphasizing that travel, and that enduring struggle while traveling, is the only way to develop your authentic self.

The digital age has enabled two things: the first, a community of people able to share their experiences and relate to readers helpful advice as well as an affirmation that they can travel too. The second, websites that enable travellers to network with other people outside of the tourism business. For example, The New York Times “Frugal Traveler” section includes, in addition to descriptions of delicious street food or adventures taken on the cheap, links to helpful websites that enable travelers to network directly among themselves. One criticism of the digital age is that it reduces humanity’s interaction with the world beyond the computer screen, but the recent rise in “authentic travelers” over the last decade suggests otherwise.

Works Cited

Petrarch, Francis. “The Ascent of Mont Ventoux.”The Renaissance Philosophy of Man.Ed. Ernst Cassirer, Paul Oskar Kristeller, John Herman Randall Jr. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1948.

Hester, Nathalie. “Mapping Petrarch in seventeenth-century Italian Travel Writing.” Humanist Studies and the Digital Age 1.1(2011).

Smith, John. A Description of New England.Ed. Paul Royster. DigitalCommons at University of Nebraska - Lincoln, 1616. eBook.

Carey, Daniel. “Anthropology’s Inheritance: Renaissance Travel, Romanticism and the Discourse of Identity.” _History and Anthropology_14.2(2003):107-123

Machado, Amanda. “How Millennials Are Changing Travel.” The Atlantic 18 June 2014. Web.

van Nuenen, Tom. “Here I Am: Authenticity and Self-Branding on Travel Blogs.” Tourist Studies(July 2015).

Image Credits

Meme by Frontierofficial / CC BY

About the Author

Nikkita Walker is a California native who uprooted herself to study literature in Utah, which should be a testament to how much she loves storytelling. She is currently a senior at Brigham Young University finishing a degree in English and upon graduation plans to never be cold again.

Building a More Creative Commons

Everyone wants to build something bigger than themselves. The Internet, for better or for worse, provides that opportunity. It’s a sort of commons: a public space where like-minded people can organize, where anyone can showcase their abilities, where diversity and cross-pollination are frankly inevitable.

The opportunities for community-building and group interaction here are unprecedented. Copyright laws and earthly credentials don’t hinder creativity when everyone is a string of ones and zeroes. Ideas and intellectual property fly free, gathering thousands of distinct yet untraceable fingerprints. Incredible new things are invented every day.

Ahead, we explore the phenomenon of fanfiction, the plagiaristic (yet unpunishable) impulse of daydreaming superfans. We examine the way that members of online communities earn their reputations, forming a group identity that is as welcoming as it is impenetrable. Finally, we take a look at the open source movement, wherein millions of programmers share and borrow each other’s code freely. In every case, we discover a public realm of uncommon creativity and expertise.

Crowd Sourcing Fiction

Nikkita Walker

I like to imagine how the Author Gods of the past might react to fan stories like Pride, Prejudice, and Zombies - a reimagining of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice - being made into novels. “Outrageous!” Mark Twain might say with an angry twitch of his mustache. “Make it new,” Ezra Pound would say with a haughty sniff. “Well,” Shakespeare would say, “people like it.” The Author Gods would turn to him in disbelief. “What?” He would say defensively, “They like it. Who cares if it’s been done before?”

This is one of the biggest criticisms directed toward the massive world that is contemporary fan fiction; artistic theft. Numerous websites like fanfiction.net offer thousands of reimagined stories from every genre, using preexisting television shows, books, and movies as a basis for their own retellings. There are even whole websites dedicated to specific stories, like harrypotterfanfiction.net and browncoats.com which cater exclusively to Harry Potter and Firefly writers and readers. Beyond the writing, there are visual art websites like DeviantArt which allow visual artists to collaborate with fan fiction writers to illustrate their writing. The argument for fanfiction today is the same as it was in the Renaissance of the past, that imitation leads to preservation and more importantly new creation. The depth of this artistic development poses a vital question: How much does the story truly belong to the original writer?

Petrarchan Snark and Renaissance Fan Fiction

The tradition of fan fiction has existed since the Renaissance. The imitation of exhumed artistic styles and writing from early Grecian and Roman times was called “ad fontes”- a return to the sources. Literary scholar Brian Vickers writes that “Where we tend to think that every literary work worthy of the name is unique, a testimony to its author’s creative originality, Renaissance theorists expected that not just beginning writers but all authors would achieve originality through the process of imitation”(Vickers 1). Francis Petrarch, the creator of the Petrarchan sonnet which has ironically been imitated to the point that it has become its own literary style, developed his talent by copying down the works of older writers like Cicero. He describes the importance of imitation and the difference between artistic interpretation of an original work and copying in a letter to a friend: “An imitator must take care to write something similar yet not identical to the original, and that similarity must not be like the image to its original in painting where the greater the similarity the greater the praise for the artist, but rather like that of a son to his father”(Bolland 481). Critic Andrea Bolland further explains that “what is sought in an artistic or poetic imitation is not the exact appearance of the model but rather the artistic “ethos” that governs the appearance”(482), pointing out that imitation during the Renaissance was less about artistic theft and plagiarism, instead focusing on the emulation of style and aesthetic beauty. Imitation was undertaken as a method of education.

Renaissance writers weren’t just borrowing from the dusty works of long-dead artists, either. For example, the name Shakespeare is still spoken in reverent tones. Yet the great playwright himself often borrowed from the works of his contemporaries. Arguably Shakespeare’s most well-known play, Romeo and Juliet, is based on the poem “The Tragicall Historye of Romeus and Juliet” which had only been written a few years earlier by Arthur Brooke. Literary critic Robert Adger Law analyzes how although the originality of Shakespeare’s play is questionable, his authorial voice and scripting is all his own, and to create the play within a pre-existing and popular poem requires a certain level of genius. Law writes that “The borrowing [of Brooke’s work] is apparent in every scene and in almost every long speech of the play”(Law 86). Arguably it was a more difficult task for Shakespeare to write his story following the plot elements of Brooke’s work than it would have been for him to write an original romance.

Any reader or aspiring writer who has encountered plagiarism issues today might be asking, How? How could this possibly be allowed to happen? What about copyright infringement? What’s important to remember is that the “ad fontes” environment was so pervasive at the time that imitation wasn’t the heinous trespass that it might be considered today, and it could perhaps be argued that because of the ungoverned creative commons shared by artists in the 1500’s, they were able to enter a fertile period of art that we call a “Renaissance” today. New modes of communication, enabled by a dramatic increase in literacy and the innovations of the printing press created a new era of communication at the time much like the digital one experienced in the present. It’s apparent from the material generated now, as it was in the past, that the source of widespread creativity comes from free communication.

Expanding the Commons

For myself, the thousands of free fan fiction stories available online saved my little fan girl life when Fox Network made the greatest mistake in the history of television and cancelled Joss Whedon’s series Firefly. But fan fiction enables readers and fans to expound on stories that they love, even after their completion. The world of the story is fleshed out to universal proportions because of the communal creativity enabled by fan fiction websites. The story becomes a kind of commons that enables storytellers to take part and shape it as they will, or answer plot holes left by the previous writer. Since Firefly’s premature cancellation it has gained a cult following that has left fans howling about unanswered questions and thankfully there are thousands of fan fiction stories about the continued adventures of the characters, proving that while the original author might have intended for an end, the matter is entirely out of his hands.

Some people consider fan fiction to be a less reputable form of storytelling, perhaps considered more childish because it is a retelling of someone else’s stories according to the whims of the fan fic writer. Writer maliciouspixie5 states that, “I would love to see someone bring fan fiction away from the ‘joke’ that some people consider it. I’ve told family friends that I just write ‘kids stories’ because to tell them the truth would be embarrassing…we aren’t all chubby little teens doing this when our parents aren’t watching. Most of the people I know writing this stuff are highly intelligent, articulate, and outrageously funny folk.” But if websites like fanfiction.net and DeviantArt allow a free space for writers and artists to make their own creations inspired by another’s stories, there is a degree of management held by the community itself. Some users dub fan fiction websites “guerilla publishing,” because it is the community of fan fiction readers and writers that determine what works are good enough to be preserved. It’s because of this community-editing ability that many people prefer more user-empowered websites like fanfiction.net to the flashier Wattpad because, as user MasterFeign points out, “Wattpad also has more lax rules, but that also means the quality of fics will be a little… terrible over there, I think.”

Fan fiction has created a whole slew of new literary devices and developed its own vocabulary; headcannons, shipping, and genderbending being among them. But just as there are rules and styles associated with writing traditional literary fiction - Slash those adverbs! Develop backstory! - so are there rules associated with writing quality fan fiction, including how a writer can interact with the original material. Headcannons and genderbending can be acceptable and even fun storytelling devices, but the most stressed aspect of fan fiction - the quality that separates it from traditional fiction - is believability. Many fan fiction readers come to the table with a great love for the original work and are driven to fan fiction because they want more of it. Fan fiction is then a self-sustaining community, writers and readers freely giving and taking stories, but with absolute respect for the original work.

DeviantArt user zoni writes that, “Personally, I have absolutely no regard for authors who sell their fan fiction to a company to be reworked as original fiction…You can’t take a piece of fan fiction and turn it into an original novel if it’s well written, for a very simple reason: fan fiction is created because people want more of something. More of that television show, that band, that manga, whatever it is. Good fan fiction is that more. It’s more Harry Potter. More Star Wars. More SHINee. And if any publisher feels A-OK with taking Star Wars, name replacing it and then publishing it, you have a problem on your hands.” Like the “ad fontes” fan fiction of the Renaissance past, the fan fiction of the digital Renaissance present represents another artistic medium, something that scholar Maria Leavenworth describes as representing “an intermediary stage between print literature and complex, often multimodal, contemporary hypertexts which to a greater extent utilize the affordances of the online environment”(Leavenworth 40).

Shipping and Genderbending

Fan fiction allows for writers to reinterpret the original work based on their own preferences. One example of this is “shipping,” creating a relationship between two characters that might not exist in the original, and “genderbending,” changing the genders of the original characters. These two techniques occur frequently in many different fan fiction interpretations, but one well-known example would be Sir Conan Doyle’s Sherlock series. In the original work, the relationship between Sherlock and his partner Watson is already very close. Contemporary adaptations of the story reflect recent feminist changes or social acceptance of openly gay behavior. In the fan fiction short story “His Pilgrim Soul Day” by user maliciouspixie5, Watson and Sherlock are partners in addition to being committed romantic partners:

“John stops him with “And WE have three years invested in US!” He is angry, so very angry now. “We were supposed to have a night for us, sans the surgery and the lab. Just us!” He takes a deep breath and tries to calm himself. His heart feels like it has a leak, one that Sherlock’s sorry just can’t fix this time. “Three years ago we said on our third year we would start looking for a surrogate. We would start our family. You were hesitant about it but said by now you would be ready” (maliciouspixie5).

Literary critic Ann McClellan writes that the BBC adaptation of Sherlock is popular in fan fiction interpretations because of the already dependent relationship, although heteronormative, between the characters. She writes that “as single men in the 20th century, the BBC Sherlock’s John and Sherlock would have to take on the reproductive labor role in their household; living together as roommates also facilitates the approximation of a heteronormative relationship whereby one person–John Watson–becomes culturally feminized by assuming these responsibilities”(McClellan). Different fan fictions take the same preexisting power dynamic from the original storyline and reinterpret it “genderbending” the characters. Often even when Sherlock is rewritten as a woman, he/she still possesses the assertiveness traditionally ascribed to male characters,whereas John possesses “homemaker” characteristics ascribed to maternal characters.

“His Pilgrim Soul Day” is an example of what most fan fiction does, which is to take the characters or situation of the original story and put them in a new context. Fan fiction writer Icarus says there is a clearly distinguished line between plagiarism and fan fiction, and that fan fiction enables “more “subversive” or “transformative” stories [to] make up the bulk of fanfiction and while they begin with the main characters and world, by the end, so much has changed they no longer “click” into the main source”(Icarus).

Rewriting the Known World

Becky Barnicoat, writer for The Guardian, says that she believes that fan fiction represents a new, democratized future of publishing which puts power in the hands of the readers rather than the publishers. She writes that the “wonderful thing about fanfic is that people just go for it - firing off chapters at school, at work, on the loo, often written on an iPhone and published for a potential audience of millions, spelling mistakes and all. This is the democratic modern publishing industry where readers decide what they like, and snooty editors with their red pens are the stuff of a really boring fanfic set in the olden days”(Barnicoat).

Fan fiction enables storytellers to take recognized stories, those that perhaps have the most impact on the social majority, and reinvent them according to the storyteller’s own conceived perception of reality. As Petrarch, Shakespeare, and Mirandola would’ve happily applauded, fan fiction is an example of using another’s work to express a new kind of “ethos.” The original story material used in fanfiction is no longer just the property of the original creator, it is the building block of a whole new social environment.

Works Cited

McClellan, Ann. “Redefining Genderswap in fan fiction:A sherlock Case study.” Transformative Works & Cultures. 17(2014)

Barnicoat, Becky. “Do Something: Creative: Seven things you need to know to write fan fiction It’s a brave new world online, says Becky Barnicoat.”The Guardian. (2014).

Bolland, Andrea.“Art and Humanism in Early Renaissance Padua: Cenini, Vergerio, and Petrarch on Imitation.” Renaissance Quarterly, 49.3(1996):469.

Vickers, Brian. English Renaissance Literary Criticism. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. Print.

Law, Robert Adger. “On Shakespeare’s Changes of His Source Material in ‘Romeo and Juliet.’”Studies in English 9.(1929):86-102.

Leavenworth, Maria Lindgren.“The Paratext of Fan Fiction.” Narrative, 23.1(2015).

Image Credits

Photo by Yarl / CC BY

About the Author

Nikkita Walker is a California native who uprooted herself to study literature in Utah, which should be a testament to how much she loves storytelling. She is currently a senior at Brigham Young University finishing a degree in English and upon graduation plans to never be cold again.

The Unspoken Caste System in Social Media

Doridé Uvaldo-Nelson

Person 1: Are you sure about this decision? There’s a lot of adjustments that come with a switch like this.

Person 2: Yes, I’ve done my research and I think I’m ready.

Person 1: But we’ve always been a united family on this matter. You’re willing to disrupt that completely?

Person 2: You realize we’re talking about a phone, right?

Person 1: Right, but…

On the surface the above conversation seems like an excerpt from an overtly dramatic comedy when you consider that Person 1’s life altering decision is simply a phone change. Yet, it’s also very realistic. Recently I had a professor tell me that after years of being an iPhone user he had decided to switch over to an Android device. I immediately gasped, my jaw dropped, my eyes widened, and I replied, “But why?”

In retrospect, what I really should’ve asked was, why is this a shocking statement anyway? It’s not like he was confessing to me that he was planning on failing the whole class or that he’d eaten a can of worms for lunch, because in all reality my reaction was better suited for scenarios such as these.

The fact that a person switching from an iPhone to an Android device—or vice versa—can trigger an excess of opinions and emotions means that at some point in the history of technology users began to identify and bond according to their device or platform of choice. There’s a sense of camaraderie that comes from knowing you are #TeamApple or #TeamDroid. And while these preferences are sometimes just indicators of interface preferences, it’s worth considering why, even in technology, humans seem to form communities and identities that define them as similar or different from others.

Techtopia, a Modern Tale

Had Thomas More been alive to see a smart phone and all of its apps today, the title of his renowned work Utopia might have been named something like Techtopia, Utopia literally means “no place” when translated from the Greek ou “not” + topos “place,” but for a long time it was believed to mean “good place” deriving from the Greek eu or good. This is an important distinction to make when you consider that for hundreds of years, scholars have debated the purpose of More’s Utopia. If Utopia does not mean a good place, but rather a “no place” then maybe More is not describing an ideal and perfect society.

Because of the way More structures the narrative of his narrator it’s unclear whether he sees this as an ideal society or total nonsense, and perhaps that was his point. It’s often the case that as humans we feel uncomfortable with ambiguity and uncertainty, and yet we must figure out how to live and thrive in it.

With the technological advances of our time there is a lot of debate on how social media outlets create communities that bring out the best or the worst in people. And depending on who it is that you speak with, they will tell you that social media is great or of the devil, and sometimes even both. But what is it that makes both of these observations valid? Perhaps by examining the types of communities that social media fosters we can better understand the great ambiguity of social media platforms.

The community of Utopia is described by More as harmonious and peaceful society, that is ruled by a representative government. There are many customs that are particular to the Utopian community at the time, one being the lack of a national religion and a belief that pleasure was the key to prosperity and joy. Everyone works together and there is no such thing as private property or currency, and even crazier is the fact that people were happy and willing participants of this type of communal living. More tells us, “Nobody owns anything but everyone is rich—for what greater wealth can there be than cheerfulness, peace of mind, and freedom from anxiety?” In other words, a sense of richness does not come from physical, tangible things, but rather from the knowledge that you have a cheerful, stress-free life.

We can take this statement at face value, or remind ourselves that More didn’t intend to create a “good place” but rather a “no place” when he wrote Utopia. So while the idea that because people don’t own their space or their property inherently leads to a happier life may sound great, it does not mean that it is good, maybe it just means that the belief is only possible in a nowhere made up land. All you have to do is take a good look at the wild and lawless plains of current social media.

Sharing is Caring?

The Internet does not physically exist in the way we think of countries and cities existing, it is like the air: we can access it most everywhere but we cannot touch it, see it, or taste it. In fact, we could say that it exists nowhere, like Utopia. So if there was any place where we could truly test the communal living patterns of the Utopian people it would through online communities. Since people of all economic, social, and political backgrounds with access to the Internet can take to social media, blogs, and other platforms to share their opinions/thoughts/stances it has been said that the Internet is the great equalizer of the masses. But a study conducted by the University of Georgia found that a communal sharing of platforms does not necessarily translate as an egalitarian. Himelboim looked at the discussions of over 200,000 participants on 35 different newsgroups over the span of six years. He found that 2% of those who started the discussions received about 50% of the responses. Despite the Internet’s user diversity, a social hierarchy emerged in a digital space that does not physically exist and that defies all ownership.

Digital Hierarchy

They say that birds of a feather flock together, and never has it been more true than when we look at online communities. According to Himelboim people create something called preferential attachment which is a fancy way to say that the more popular you are, the more popular you get. People prefer responding and interacting with a person who has an established network and credibility. And the larger a group/community gets, the more “skewed the network of interaction becomes.” For example, Twitter. A Pew Research study found that although an immense number of tweets are tweeted on a day to day basis, about 70% of tweets get ignored, which means they receive no likes, retweets, or replies.

Identity Through Community

There’s a saying in Spanish that says: tell me who your friends are and I will tell you who you are. My mother used to say this to encourage me to hang out with good people, but let’s think about it in terms of social media platforms. If someone told you that their preferred platform was Pinterest, would you immediately make assumptions about who they are and what they care for? It’s highly likely, and you wouldn’t be alone in that. Stereotypes about platforms have emerged because in the Techtopia of our day, self expression and identity are inevitably connected to our digital communal sharing.

Of course, most people use more than just one type of social media platform, but the classifications of the individual platforms beg another interesting question: What came first, the community or the mold? Was Instagram initially designed for the selfie, or did it become Instagram because of the selfie? Was Pinterest intended mainly for women who care for DIY projects or did women who care for DIY projects make Pinterest what it is today?

While marketing and tech-savvy CEOs may argue that the their platforms were all along intended to work in the way they work right now, therefore proving their success, the massive amount of updates these apps go through to meet their consumer’s needs may indicate otherwise. Because although a platform may have started out as, say, a college student networking site (in the case of Facebook), as the social media community’s identity developed the platform adjusted to better fit the mold of its users. This ultimately proves that users have the final say when it comes to community building.

Works Cited

Bennet, Shea. “Social Media Stereotypes, Statistics, Facts And Figures 2012 [INFOGRAPHIC].” SocialTimes. AdWeek, 14 Nov. 2012. Web. 14 Nov. 2015.

Caudle, Mildred Witt. “Sir Thomas More’s “Utopia:” Origins and Purposes.” Social Science 45.3 (1970): 163-69. JSTOR. Web. 1 Dec. 2015.

Himelboim, I. “Civil Society and Online Political Discourse: The Network Structure of Unrestricted Discussions.” Communication Research 38.5 (2010): 634-59. SAGE. Web. 4 Dec. 2015.

Himelboim, I. “Civil Society and Online Political Discourse: The Network Structure of Unrestricted Discussions.” Communication Research 38.5 (2010): 634-59. SAGE. Web. 4 Dec. 2015.

“Mobile Messaging and Social Media 2015.” Pew Research Center Internet Science Tech RSS. The Pew Charitable Trusts, 19 Aug. 2015. Web. 15 Nov. 2015. More, Thomas. “Utopia.” Project Gutenberg. IBiblio, 22 Apr. 2005. Web. Nov. 2015.

Image Credits

- Pixaby Public Domain Photo

- ⓒ 2015 Doridé Uvaldo-Nelson

About the Author

Doridé is a student at Brigham Young University. She is majoring in English and minoring in Women’s Studies and plans on graduating December 2015. Her work has previously appeared in Salt Lake Magazine and Insight, the BYU Honors magazine.

Free Code and Renaissance Plagiarism

Isaac Lyman