Table of Contents

Sampler edition of ‘Disciplines of Dowsing’

by Tom Graves and Liz Poraj-Wilczynska

This sampler-edition ebook of Disciplines of Dowsing is based on the first edition of the book, as published by Tetradian Books in 2008. Chapters highlighted in bold are included in this sampler-edition.

- Introduction

- Dowsing in ten minutes

- A question of quality

- The disciplined dowser

- The dowser as artist

- The dowser as mystic

- The dowser as scientist

- The dowser as magician

- The integrated dowser

- Seven sins of dubious discipline

- Practice – enhancing the senses

- Practice – setup and fieldwork

- Practice – worked examples

- Appendix: Resources

The Disciplines of Dowsing

The Disciplines of Dowsing

Tom Graves

Liz Poraj-Wilczynska

Published by

Tetradian Books

Unit 215, 9 St Johns Street,

Colchester, Essex CO2 7NN, England

http://www.tetradianbooks.com

First published: September 2008

ISBN 978-1-906681-08-1 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-906681-09-8 (e-book)

© Tom Graves & Liz Poraj-Wilczynska 2008

The right of Tom Graves and Liz Poraj-Wilczynska to be identified as authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Contents

Introduction

- A bit of background

- An emphasis on quality

- Dowsing and beyond

- A question of discipline

- Killing quality

Dowsing in ten minutes

- What is dowsing?

- Know your instrument

- It’s all coincidence

- What’s the need?

- Round the bend

A question of quality

- Predictable quality

- Subjective quality

- Quality in practice

The disciplined dowser

The dowser as artist

- Principles…

- …and practice

The dowser as mystic

- Principles…

- …and practice

The dowser as scientist

- Principles…

- …and practice

The dowser as magician

- Principles…

- …and practice

The integrated dowser

- Principles…

- …and practice

Seven sins of dubious discipline

- The hype hubris

- The Golden-Age game

- The newage nuisance

- The meaning mistake

- The possession problem

- The reality risk

- Lost in the learning labyrinth

- Cleansing the sins

Practice – enhancing the senses

Practice – setup and fieldwork

- Preparation

- Arriving on site

- Fieldwork and records

- Closing the session

Practice – worked examples

- Techniques summary

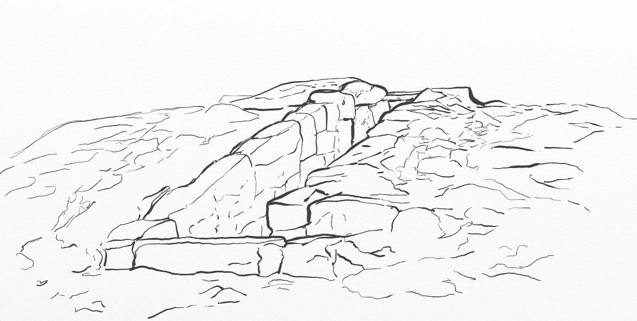

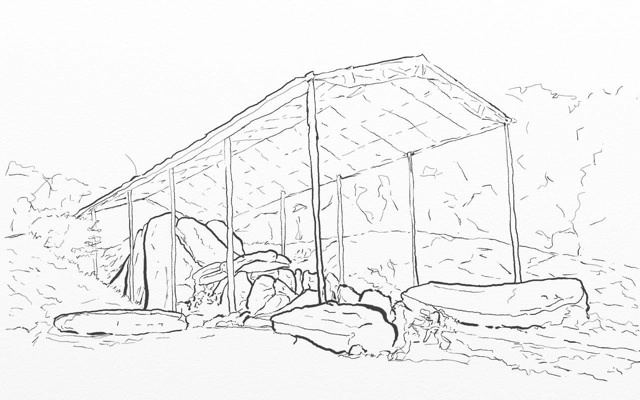

- Belas Knap, Winchcombe, near Cheltenham

- Wiggold, near Cirencester

Appendix: Resources

- Books and text resources

- Societies

Acknowledgements

Amongst others, the following people kindly provided comments and feedback on the themes and early drafts of this book: Gerry Beskin (London, GB), Colin Clark (Cheltenham, GB), Paul Devereux and Charla Devereux (Cotswolds, GB), Norman Fahy (Castle Rising, GB), Valerie Graves (Colchester, GB), Gordon Ingram (Writtle, GB), Helen Lamb (Malvern, GB), Kevin Masman (Castlemaine, Aus), John Moss (Malvern, GB).

Please note that, to preserve confidentiality, stories and examples have been adapted, combined and in part fictionalised from experiences in a variety of contexts, and (unless otherwise stated) do not and are not intended to represent any specific person or organisation.

Introduction

A bit of background

A book on dowsing, yes; but why the disciplines of dowsing? What’s the difference? What’s this all about?

Two reasons, really.. The first is that whilst there are plenty of good beginner-level books on dowsing, there are very few that go beyond that beginner stage. And almost all of those are on the general lines of “I did it my way” – which is interesting, of course, but not much help for identifying general principles from which we can improve the quality of dowsing work. This book aims to fill that gap.

In case you don’t know dowsing at all, we’ve included a brief introduction here – see the Dowsing in ten minutes chapter. But after that we’ll go straight into principles – the four core disciplines of dowsing, and the bridges between them – and show you how to adapt them in your own working practice.

The second reason for this book is around the need for quality in dowsing. Between us we’ve been involved in various aspects of the field for a fair few decades now: and it’s painfully clear that far too much of the dowsing work being done at present – especially in the study of earth-energies and the ‘earth-mysteries’ field in general – is of dubious quality at best. To be rather less polite about it, much of it is meaningless junk. Kind of pointless, really…

No matter how good the showmanship may be, we cannot escape the fact that quality depends on adherence to some basic rules and guidelines: and if the guidelines are ignored, the results cannot be anything other than rubbish. Which is a problem: a big problem. So here we’ll not only describe the guidelines – those Four Disciplines of Dowsing, and the links between them – but show you how to verify the quality of your work, and avoid the Seven Sins of Dubious Discipline. It’s only then that dowsing becomes useful.

In a sense, though, none of this is specific to dowsing. These concerns about principles, adaptation and quality are generic to all skills – especially those with a large subjective component. As one frustrated friend put it the other day, “I’ve had all these experiences and done all these trainings – shamanic journeys, earth magic, healing groups, meditation, ritual, spirit guides, animal energies, all that stuff – but what do I do with it? What’s the use?” One answer is just to celebrate it – enjoy it, accept it for what it is, and leave it at that. In other words, leave it in what we describe later as the modes of ‘artist’ or ‘mystic’. But to use it, to do something with it, in what we’d call the ‘magician’ mode, requires a purpose, a direction, a reason – and better quality.

In essence, if we’re going to get anywhere useful, we need to get beyond the dilettante ‘taster’, and commit to the skill. As we’ll see shortly, we also need to accept that we’re going to have to go round the bend a bit in order to go deeper, which in places is not comfortable at all. But that’s the only way we’re going to lift the quality of the work – and whatever we do, and however we do it, quality really does matter.

An emphasis on quality

Quality sounds serious. Don’t worry, this isn’t that kind of book – it’s perfectly okay to have fun and play around! In fact it’s not only a good idea, but really important to do so, for a lot of reasons – not least because it’s one of the few ways we can get round the fear of failure that would otherwise cripple all of our work. But – and it’s a big ‘but’ – what we find there in play is ideas, not facts. We need to choose that mode, deliberately, consciously, and know that we’re in that mode: but don’t treat the results of that ‘playtime’ as anything other than the output of the artistic idea-creating space.

There’s a place for seriousness, and a place for play. But we need to be very clear as to which is which. If not we’ll find ourselves on the dreaded New Age ‘pub-crawl’, full of glamour and grandiosity, full of excitement and exuberance, but somehow never quite managing to reach a useful outcome – “an empty thunder, signifying nothing”.

Where there’s reasonable quality, the work has a lot more meaning, and it’s a lot more fun, too. It’s not that hard to create quality, either: much of it comes down to a simple acronym, LEARN – eLegant, Efficient, Appropriate, Reliable, iNtegrated. There are some useful tips and tricks, too, that we can draw from the quality-standards used in business: they’re from a different context, of course, but as we’ll see later, the exact same principles would apply in dowsing and much else besides – and it doesn’t take much to adapt them to our purpose here. More on that in the chapter on quality – see A question of quality.

Dowsing and beyond

So what is “our purpose here”? These quality-concerns are not just about dowsing: they apply to any kind of subjective exploration. Yet we’ll keep the focus here on dowsing and the ‘earth mysteries’ field, to give us something specific to work with yet not drown in too many examples or side-excursions. Even if your core interest, though, is in a somewhat different field – healing, perhaps, or the so-called ‘psychic’ skills – you should still find plenty here that’ll be relevant to you, and we’ll trust that you’ll be able to adapt it to your work as you need.

Let’s play with an example here. When we put earth-mysteries studies to practical use, it’s called geomancy: feng-shui is perhaps the best-known form of this, though there are many others. It’s a broad field, with a very broad scope, but we could summarise how quality impacts on geomancy in generic form as follows:

Quality is a matter of skill. It requires experience – which we don’t get just from sitting in an armchair. It requires judgement, awareness, dexterity, discernment, even that rarity called ‘common sense’. It calls for a good understanding of the mechanics of the problem at hand, the choice of approaches to that problem, and the trade-offs that lead to appropriate methods in any given context. It requires an ability to balance between the content and the context of the problem. And yes, it kind of demands that we go round the bend a bit, in the labyrinthine process of learning each new skill…

Quality is a matter of luck. In feng-shui, for example, they talk about three kinds of luck:

- heaven-luck – what happens as a result of our nature, of who we are, the milieu in which we live, and so on

- earth-luck – what happens because of where we are, our surroundings and the like

- man-luck – about our choices in finding a balance between heaven-luck and earth-luck, and how we use those choices.

So whilst we never have control, we always have choice – though there’s always a weird twist somewhere in those choices! Murphy’s Law is the only real law that there is, but it’s so much of a law that it has to apply to itself too – which is where ‘man-luck’ comes to play. Hence what we might call ‘inverse-Murphy’: things can go right if we let them – but if we only let them go right in expected ways, we’re limiting our chances! Hence too much of geomancy is not only the art of being at the right place at the right time, but not being in the wrong place at the wrong time…

Quality is a matter of belief. Let’s face it, much of what we do in dowsing, geomancy and the like is pretty crazy, by any ordinary standards. Yet as scientist Stan Gooch put it, there’s an important paradox at play here: things not only have to be seen to be believed, but also have to be believed to be seen. In subjective skills, beliefs are tools: they play a key role in how well we’ll be able to achieve the intended result. But there’s a catch, of course. Sometimes things can work – for a while, anyway – because we want them to, or because we’ve paid the issue some attention: yet if we’re not careful about it, when the belief fades, so do the results. And we also need to be very careful to learn the boundaries between reality and wishful thinking…

Quality is a matter of context. Rules and guidelines are useful, but only useful: we forget that fact at our peril.. Every theory or model expects ‘sameness’, or at least close similarity; yet every place, everything we deal with, is itself, different and distinct. So a key part of geomancy, and the practice of dowsing and similar skills, is about knowing to stick to the rule-book, and when to try something else. The rule-books define the likely content; yet in practice it’s context that determines what will work, and what won’t…

Dowsing is a really good test-case for all of this, because there’s almost nothing to it other than those subjective skills. (As we’ll see in the next chapter, the physical skills we need for dowsing are trivial: you can pick the basics up in a couple of minutes. It’s the rest of the skill that’s not so trivial…) So even if dowsing isn’t your usual forte, do have a play with it here: there’s much you’ll learn that you can apply to every skill or discipline.

Which brings us back to this matter of discipline: what’s all that about, you might ask?

A question of discipline

A slight risk of confusion here, perhaps, because we’re dealing with two meanings of ‘discipline’ here – and both of them are valid.

One is the fact of discipline itself, doing things consistently – resolving the mechanics and approaches to that skill, in a manner that’s elegant, efficient, appropriate, reliable, integrated. That’s the only way we can achieve and maintain quality in our work. More to the point, if we don’t do that, what we get is rubbish – even if at times we can perhaps try to pretend otherwise… If we want our work to mean something, there’s no way to get round this: discipline matters.

The catch is that subjective skills such as dowsing depend on a personal balance between the mechanics and approaches: there’s no predefined “the right way to do it” that works for everyone, and certainly no fixed method that covers everything. There are some generic principles that work well – see A question of quality – but otherwise that’s about as close as we get to “the method”. Beyond that, we need to move up one step to a kind of meta-level, to get to what we might call ‘the methods to derive methods’.

This is the other meaning of ‘discipline’: disciplines – the plural – are what we use to guide the discipline of our work. At the practical level, each kind of work has its own disciplines – the disciplines of water-divining, healing, archaeological survey, earth-energies and so on. What we’re interested in here are the disciplines at the next level up, that guide quality and choices within each of the practical disciplines. We could describe the different modes of these ‘meta-disciplines’ – see the chapter The disciplined dowser – as the Four Disciplines of Dowsing:

- a discipline of sensing – see The dowser as artist

- a discipline of belief – see The dowser as mystic

- a discipline of fact – see The dowser as scientist

- a discipline of action – see The dowser as magician

The ‘artist’ mode is about ideas, experiences, whilst the ‘mystic’ mode is more about meaning, belonging, deep belief and so on. We also need to link all these different modes together into a unified whole, such that each mode consistently supports the next – see The integrated dowser. We’ll show later how all of this comes together, with some detailed worked examples in dowsing and archaeography – see the ‘practice’ sections, starting at Practice – enhancing the senses.

But if we don’t do this in a disciplined way – for example, if we play a random New-Age mix-and-match between the modes – we won’t get useful knowledge, we’ll get a useless mess. In short, we need to be clear which mode we’re in at every moment, and act accordingly – don’t mix ‘em up!

Killing quality

Mixing the modes is just one of many ways to kill the quality in our work. Some of the (many) others include:

- getting caught up in the hubris and hysteria of hype

- losing sense in the quest for some imagined ‘Golden Age’

- indulging in the casual New Age carelessness that we could unkindly call ‘newage’

- making mistakes about the meaning of meaning

- trying to cling to certainty and ‘truth’ by possession

- failing to allow for the risks of a reality in which ‘real’ and ‘imaginary’ can collide in unexpected ways

- skipping over skills-development steps in the labyrinthine process of learning

More on all of those later – see Seven sins of dubious discipline. But again, this isn’t just about dowsing – it applies in general to anywhere that involves any kind of subjective exploration. For instance, at times we’ve seen archaeologists come up with some absolute howlers, in terms of ill-thought-through explanations of ancient sites; and most of the attempts by self-styled ‘skeptics’ to explain dowsing – or, more often, to dismiss it – have been almost text-book examples on how not to do science. Discipline matters in every discipline.

In our ‘practice’ sections’ starting at Practice – enhancing the senses, we’ll cover a broad range of areas, showing how to identify and avoid those mistakes, and maintain discipline whilst moving between the modes. As we’ll see, there are a fair few challenges there, and sustaining that discipline does take practice.

But then so does dowsing itself: and in case you’re not familiar with that as yet, that’s what we need to turn to next.

Dowsing in ten minutes

Okay, we’ll admit it, this might take a bit more than ten minutes – but it’ll be quick and easy, anyway.

What is dowsing?

Dowsing can be found in such a wide variety of forms and with so many different uses – from water-divining to healing, from geomancy to radiesthesia, and a swathe of subtler variants such as ‘deviceless dowsing’ – that if we look only at the surface appearances it can seem a little difficult to say exactly what it is. But if we jump upward a step or two, what they all have in common is this:

- we’re sensing something (though at the moment don’t worry too much about just how or what we’re sensing…);

- we have some means to identify the location of that sensing (though ‘location’ can be a pretty broad term here…);

- we have some way – some question in mind – to derive meaning from that coincidence (‘coincide-ence’) of sensing and location;

- the whole point of all this is to put it to some use.

Take the example of the stereotype water-diviner – a gnarled old man with a gnarled old stick. The bent twig seems to be part of the process, but its real role is to make it easier both to sense the water below, and to know when he’s sensed it. When the rod goes up or down or whatever, that’s the right location. X marks the spot. it means there’s water there, he says. Which, if you dig down to the right depth, will lead you to water you can use. This isn’t a game he’s playing: there may well be livelihoods at stake, or lives, even. And if he’s running a full-scale drilling-rig on ‘no water, no pay’ – as many of the professional water-diviners do – he has another darn good reason to make sure his dowsing is good, too. Quality matters.

And let’s take another stereotyped example, the distant-healer at her desk, holding a lock of her client’s hair in one hand and waggling a pendulum with the other hand over a list of ailments and cures. A twirl of the pendulum one way means ‘Yes’, she says; the other means ‘No’; all the sensing is simplified down to just those two choices. The location here is virtual, or metaphoric: is there a match to this place in the body, this item on the list? The lock of hair helps her to maintain her focus on this specific client – the person to whom this dowsing would be of use – which is also, in its way, a kind of location in social space. Put this all together, to derive meaningful coincidence – in this case identifying the needs and concerns of the client. Or should be, anyway: the results would be meaningless, even downright dangerous, if the quality of dowsing is poor. Once again, quality matters.

Let’s jump sideways even further, to an example that at first you might not think of as dowsing: a massage therapist, pressing fingers gently but firmly along the client’s arm. The fingers themselves are the ‘dowsing instrument’ here, deriving different feelings or sensing at specific locations on the arm, or elsewhere in the client’s body. What those sensings mean to the therapist depends on the conceptual frame in use: it may be physical anatomy, acupressure points, auras, whatever – at this metaphoric level they’re all much the same. But the aim, the use here is to help the client get well, or stay well – there’s a practical purpose for all this activity. And the point, once again, is that if the quality isn’t there, there’s no point in doing the work.

These examples may seem worlds apart, but the underlying principles are exactly the same: some form of recognisable sensing; an identified location; meaningful coincidence of sensing and location; and a use or purpose for all of this.

See let’s look at how all of this works in practice.

Know your instrument

Whenever we go out dowsing on site, there’ll always be some spectator who asks “does it work, then?” But the question misses the point: it doesn’t ‘work’ as such – you do. A dowsing instrument – the rod or pendulum or picture-postcard or whatever – can make it easier to see what’s going on, but it’s not essential: the real instrument is you.

What the visible instruments do is make your own sensing more visible to you. A divining-rod springs up because your hands move slightly. The same with the sideways movements of the angle-rods – as we’ll see in a moment. And much the same with the pendulum – the old builders’ plumb-bob, or a ring on a string – swinging sideways or in circles because your hand moves slightly fore-and-aft or side to side. So there’s nothing special at all: in every case, the instrument moves because your hands move – nothing more than that.

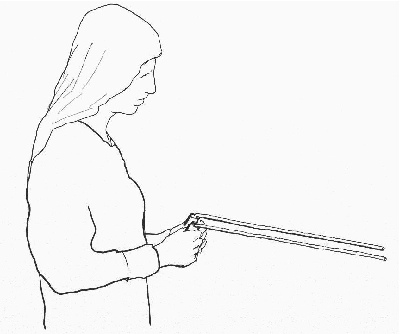

Let’s look at angle-rods first. These act as mechanical amplifiers or indicators for small rotational movements of the wrist: move your hand a little, and the rod moves a lot, in much the same way as the handlebars do for steering a bicycle.

Holding angle-rods

They’re typically made out of fencing wire or an unravelled coat-hanger, bent into an L-shape. Pretty much anything goes – we’ve seen people use folding radio-aerials, or metal ‘blades’ custom-made by a blacksmith – but the mechanical criteria for angle-rods are that:

- the vertical shaft turns freely in your hand – so it can move smoothly ‘by itself’

- the horizontal arm is long enough to break ‘starting friction’ without being so long as to be a nuisance

- the horizontal arm is reasonably straight – so you can see where it’s pointing

- there’s a tight right-angle between vertical shaft and horizontal pointer – so, again, it can turn freely

- the material is light enough to hold and to turn freely, but heavy enough to not get caught in the wind

Medium-gauge fencing-wire with a horizontal arm of around twelve to eighteen inches (30-50cm) and a vertical shaft of around three to six inches (8-15cm) will satisfy those criteria well. It can also be helpful to use handles or sleeves for the vertical shaft, perhaps made from wood or cotton-reels or a discarded ball-point pen, but they’re not essential.

Some people use only a single rod: it works well as a pointer to follow a direction. But paired rods give more choice of expression – cross-over, pointer, parallel and so on – so we’ll use that in what follows.

In practical use of the rods, we’ll see wide variations in personal style; but remember that the role of the rods is to act as amplifiers for small movements of the wrists. So the mechanical criteria here are that:

- the horizontal arm needs to be able to swing freely from side to side – hence handles are useful, but not required

- the horizontal arm needs to be just below a horizontal level – if it’s too low there won’t much amplification, if it’s too high it’ll be too unstable

- the wrist needs to be able to rotate freely – the best posture for this is with your arms about body-width apart at waist-height, with the forearms roughly level with the horizontal

So, for example, we’ll often see people holding the rods with hands close together, clamped tight against the chest; but in practice it’s perhaps not a good idea. It might feel safer, perhaps, or more controlled, but for purely mechanical reasons, holding the rods in that way will make it harder to get good results. Keep things simple, keep it free and easy, to give quality a chance to come through.

The classic angle-rods response is the cross-over – also known as ‘X marks the spot’. But we really need to develop a full vocabulary of responses, to give us a broader ranger of pointers to interpretations. Some common examples include:

- cross-over – the point where the rods cross is the location

- squint (rods leaning slightly towards each other) – often used as active-neutral, such as when tracking along a line

- double-point (both rods pointing to one side) – in tracking, line bends in the direction shown by the rods

- single-point (one rod continues to point forward, the other points outward or across) – in tracking, typically implies a junction, or another line crossing at a different level

- splay (both rods pointing in opposite directions) – T-junction on a line, or dead-end

- spin (one or both rods spinning) – variously interpreted as a ‘blind spring’ (water moving up or down), or some kind of ‘energy node’

- null (both rods exactly parallel, accompanied by a ‘nothing’ feel) – passive-neutral, often implies ‘lost it’, lost the connection

As for what this means? Well, more on that in a moment. First, though, the other most common instrument, the pendulum.

Holding a pendulum

This is a small weight suspended below the fingers, so that, again, a small side-to-side movement of your hand is made more visible. The mechanical criteria are as follows:

- the closer the weight is to symmetrical in shape, the more stable and predictable in response

- a point at the base of the weight makes it easier to see what’s going on

- the string-length should be constant – hence holding the string between finger and thumb is more reliable than draping it over a finger

- the string-length determines period of swing, and should ideally match the natural resonance of the hand- and arm-muscles – hence a typical length of around one to three inches (3-8cm)

- the weight needs to be light enough to respond quickly, but heavy enough to not be blown around by the wind

From the above, the ‘best’ pendulum is a spherical shape with a point, such as smallish version of a traditional brass builder’s plumb-bob; use a lighter one for indoor work, a heavier one on site. In principle, though, you can use whatever you like – we’ve seen people use anything from a tiny crystal to a wooden toy-soldier, from a four-pound pottery gnome to a used teabag – but note that it does tend to get harder to use the further you go from those mechanical criteria.

There’s also one mechanical criterion about usage, to do with starting-inertia. Some people use a ‘static neutral’ – in other words the pendulum indicates neutral when it’s completely still. The problem with that is that it takes time for the pendulum to ‘wake up’, in a mechanical sense – which means that you may have already moved past a point by the time there’s any visible response on the pendulum. So we usually recommend a ‘dynamic neutral’, where a small forward-and-back movement indicates neutral, because the pendulum can ‘wake up’ much more quickly.

Many people use opposite rotations to distinguish between positive and negative responses to questions – for example, clockwise means ‘Yes’, counter-clockwise means ‘No’. As with the angle-rods, though, it’s useful to build a broader vocabulary of responses, including:

- positive and negative – clockwise and counter-clockwise, as above, are typically used for this

- pointer – typically, the angle of swing indicates direction

- ‘idiot’ response, as ‘unask the question’, because the context is such that neither ‘Yes’ nor ‘No’ would make sense – a side-to-side swing is often used for this

- null, the ‘lost it’ response – a dead stop is often used to indicate this, confirmed by a ‘nothing’ feel

Whatever the instrument we use, the trick is that it should feel as if it’s moving all by itself. Just remember that it isn’t: it’s the hands that are actually doing it.

As for why the hands are moving, and what it all means – well, it’s just coincidence, really… And to make sense of that, we need to look a little more closely at ‘coincidence’.

It’s all coincidence

Dowsing is all about finding a coincidence between what you’re looking for, and where you are. The complication is that the ways we define what we’re looking for, and sometimes even where we are, may well be imaginary, in the sense we create some kind of image of them to work with. So when someone dismisses dowsing as “entirely coincidence and mostly imaginary”, we might have to sort-of agree with them, because it is indeed entirely coincide-ence and mostly image-inary.

Let’s put that in more practical terms:

- you need some way to define what you’re looking for

- you need some way to identify where you are

- you need some way to recognise the coincide-ence between them

To define what you’re looking for, the classic method is to carry a sample or ‘witness’ – a small bottle of water, perhaps, or a chunk of copper wire or drain-pipe or Roman tile or whatever the target might be. It’s easy, it’s obvious, it’s tangible, and it makes sense; it’s certainly the best approach to use when you first start dowsing. Yet oddly it’s clear that this physical sample isn’t actually required, in the way that it would be for a machine-based sensor. In fact there’s one well-known commercial set of dowsing-rods, used by maintenance crews on councils across the country, whose manual insists that whatever sample is held will be what is not found – so you find a clay drainage-pipe, for example, by not getting a response with a clay sample. Other people will use a photograph or a word or symbol as the ‘ sample’ – it’s often done that way in healing-related dowsing, for example. And for so-called ‘energy dowsing’, there’s no physical sample that we can carry: instead, we have to use some kind of imagined pattern or symbol, or look for an identifiable ‘signature’-pattern of responses.

The same applies to identifying the location. The simple way is to walk around, so that the location called ‘where I am’ is literally wherever I am – the leading edge of the leading foot is a useful marker for this. But again, this isn’t an absolute restriction: we can instead imagine ‘where I am’, on a map, a drawing, an abstract diagram or the like – hence map-dowsing and so on. It gets harder, and potentially less reliable, the further we move away from the physical realm: but there’s nothing to stop us doing so.

A classic example of this is what’s known as the Bishop’s Rule, a depth-finding technique that’s been used by water-diviners for well over a century. We start off by finding water in our usual way, with a water-sample, or a colour-coded disc, or whatever. Typically, the best spot is going to be where two water-lines cross, or spiral upward in what’s known as a ‘blind spring’. We mark that point. We then walk away from that spot, this time dowsing for the depth of the water there. At some point there should be another response. We then apply the Bishop’s Rule, which asserts that distance out is distance down: the distance away from the water-line is the depth.

We identify a ‘meaningful coincidence’ from the instrument’s responses: the rods cross, the pendulum swings in a circle, and so on. The point is that we decide beforehand what will be meaningful, and what will not – much like tuning a radio to separate out ‘signal’ (the information we want) from ‘noise’ (which is everything else).

No-one knows how any of this ‘really works’: it just does. (Or at least, with practice it does!) What we do know is that belief seems to play an important part. So here we run up against Gooch’s Paradox: things not only have to be seen to be believed, but often also have to believed to be seen. If we don’t believe that dowsing can work, we’re right – it doesn’t work. It won’t work well if we don’t pay attention to what we’re thinking; and it also often won’t work if we try too hard. Getting the balance right around that paradox is one of the trickiest parts of the skill of dowsing…

One of the other points that’s known about dowsing is that it’s similar to our other kinds of physiological perception. This differs from pure physical sensing – such as with metal-detector, for example – in that what we perceive is always an interpretation, not the thing itself; and whilst it’s good at identifying edges or other kinds of sharp change, it’s not so good with continuities or with subtle change. To give an everyday example, our eyes are very good at noticing when something flicks past in a second or so, but are not so good at spotting changes that take place over minutes or more; and when given something that is completely continuous – such as in the ‘white-out’ of a blizzard – most people will start to hallucinate quite quickly, as the eyes try to create edges where none exist at all. The same is true in dowsing. What we perceive seems to be made up of edges, but that isn’t necessarily what’s ‘really there’ – it’s just the way we perceive it.

So whilst may we talk about ‘water lines’ or ‘underground streams’, for example, what’s actually down there below is unlikely to be the subterranean equivalent of a pretty babbling brook. If we dig down, what we’re more likely to find is a band of seepage through small cracks and fissures, perhaps without even a clearly-defined cut-off between ‘stream’ and dry rock. But we’ll perceive this as a distinct line, centred on the mid-point of the seepage, perhaps with an apparent width indicating the amount of flow. In other words, what we perceive is always going to be in part ‘imaginary’, because of the way that perception creates these pre-interpretive overlays. The same especially applies to ‘energy lines’ and the like: there’s probably no direct equivalence to anything physical, but we perceive them as if they’re physical lines. We do need to remember, though, that they’re technically ‘image-inary’ – with everything that that implies in terms of conceptual quality. More on this later.

What’s the need?

There’s also what we might call ‘aspirational quality’, or ‘ethical quality’, in that need seems to be a factor in determining what works and what doesn’t. Again, we don’t know why, but it’s a common experience that results tend to be more reliable if there’s a genuine need – and especially a need on behalf of others rather than for ourselves.

Many dowsers use a checklist for need, which they use before starting any work on-site:

- Can I? – am I capable of doing the work? do I have the required skill and experience?

- May I? – do I have both the need and the permission of the place or context to do the work?

- Am I ready? – am I in the right physical and mental state to do the work?

If any of the answers is ‘No’, we should stop work straight away – otherwise the results are all but guaranteed to be unreliable.

This ‘equation of need’ also seems to be one reason why scientific-style ‘tests’ of dowsing tend to fail, or at least give ambiguous results. Members of the Skeptics Society and the like will point to such problems as ‘proof’ that dowsing ‘cannot work’, but in fact it’s an inherent fault in science, not in the dowsing. To make sense in scientific terms, we need to be able to repeat conditions exactly, and only vary one parameter at a time. But if need is part of the overall equation, we have no repeatable controls for the ‘need’ factor, and hence no way to conduct a meaningful test. Which is a problem.

Yet it’s only a problem if we depend on science for our belief. Instead, we can take a technology view, concerning ourselves not with ‘how it works’, but ‘how it can be worked’. The laws of science, it seems can never be broken, so statistically we should end up with its predicted nothing-much-ness. But whilst the ‘laws of science’ can’t be broken as such, inverse-Murphy shows us that, under the right conditions, they can be bent, locally, and sometimes a lot – which gives us the gap in which we can do our work. We just need to remember that whenever we do so, it’s Murphy that’s in charge here – with everything that that implies, too!

A more subtle concern around ‘need’ in dowsing relates to its nature as a skill. The process of developing a new skill – any skill, that is, not just dowsing – will always bring up some personal challenges around commitment to the skill itself. To get through those challenges, we have to find some way to access our own passion for the skill – a drive to improve, no matter what it takes. If we can’t find that burning ‘inner need’, our skills – and the quality of our results – may well fade away to nothing.

This applies at every stage of the process, but particularly so at that bleak point known as ‘the dark night of the soul’. To understand this better, and what to do about it, we need to go round the bend a bit – by taking a brief detour through the labyrinthine process of learning.

Round the bend

The usual view of skills-development is that it’s a linear process: we gain a steady increase in ability, each layer of training building upon those before. That seems obvious enough, yet in practice it doesn’t describe the difficulties, the uncertainties, the common feeling of ‘one step forward, two steps back’, that are so often experienced in skills-development, and which make the development of any new skill so challenging. It’s also far more than mere training: it’s the education of experience, literally ‘out-leading’ that experience from within the inner depths of each person.

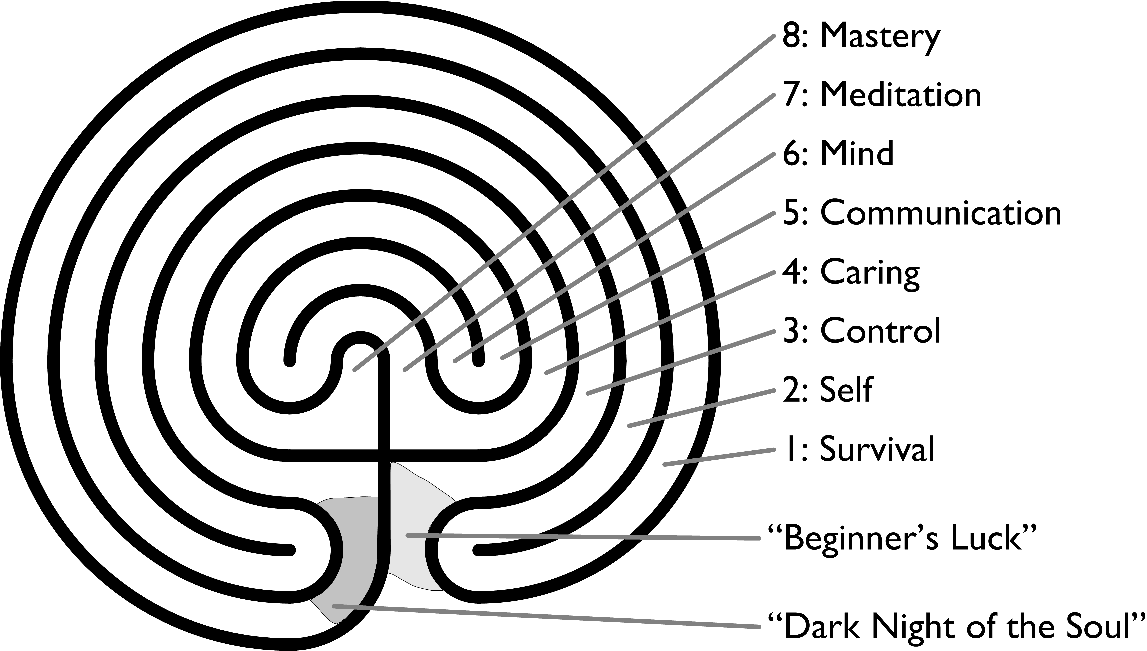

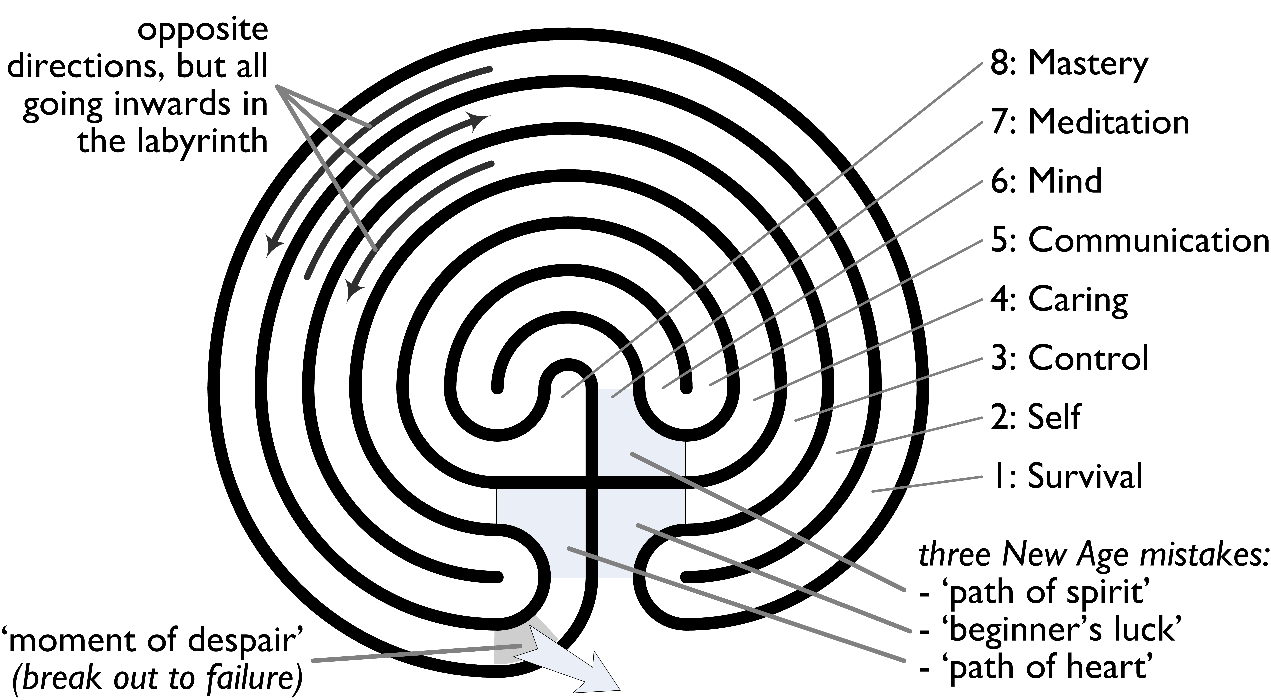

The ‘skills-labyrinth’ provides a precise metaphor that deals with these issues, in a way that’s common to every skill – so it makes the learning of any skill an easier, less stressful experience. It uses the classic single-path maze – found in many cultures around the world – to model the various stages in the personal process of learning new skills.

The skills-labyrinth

The classic labyrinth pattern is a kind of maze, but with only a single twisted path. There are no choices, no branches, no junctions – so as long as we can keep going, we will eventually get to the centre. Yet with all skills, reaching that central goal – the personal mastery of some aspect of the skill – can take a lot longer than we’d expect: and there are plenty of opportunities to get lost along the way…

The most useful version for this has seven distinct sections, in what would seem to be a linear order: survival, self, control, caring, communication, mind, meditation, mastery. But that’s not the sequence in which we experience them…

We start with ‘beginner’s luck’, the classic one-weekend-workshop ‘success’ where we succeed because we don’t know what we’re doing. There’s then a choice: either run away from the challenge – an all too common characteristic of the dilettante New Age mindset – or dive into the depths of the skill itself. If we do keep going, we move straight into ‘control’ – the limited sort-of-mastery that we can attain through training. But to go deeper, we have to go outward, to look at ‘self’, our own involvement in the skill; and then outward again, to the long, slow, painful and often barely-productive ‘survival’ stage – practice, practice, practice, often without much apparent point.

At the end of that ‘survival’ section is the worst point of all, where many people give up and abandon the skill forever. Traditionally known as ‘the dark night of the soul’ – and the exact opposite of the exuberance of ‘beginner’s luck’ – it’s often experienced the day before the exam, or the first live demonstration on-site, or some other crucial challenge. There is a way through that bleak stage: caring – a commitment to the self and to the skill itself, as much as caring in general – is the essential attribute that helps this happen. From that moment on, the skills learned so far are never lost – although as the model shows, there are a few more twists and turns to go before true mastery can be achieved!

The labyrinth model is fractal, or ‘self-similar’, in that it applies as much within each stage of skills-development as to the overall skill. As we’ll see later, in the section on Lost in the learning labyrinth, it illustrates several common mistakes, such as the tendency to cling on to the brief success of ‘beginner’s luck’. (Playing New Age dilettante is fun, of course, but nothing actually improves…) It shows how interactions between people at different stages of a skill will contribute to confusions and mistakes; it also helps explain why reliability and proficiency necessarily go down during some stages of development. And by showing that the ‘dark night of the soul’ is an inherent part of the process, it helps to reduce the risk that people will abandon their development of skill at the moment before success – at what would be great cost to themselves and their self-esteem.

Developing our skill in dowsing is the only way we’ll improve the quality of our dowsing. In turn, though, we also need to be able to identify what quality actually is – and in particular, the key distinctions between objective and subjective quality that underpin quality as a whole. That question of quality is what we need to look at next.

A question of quality

What is quality

What is quality? In the practical worlds of manufacturing and production-management, they have a definite answer to that question: quality is a kind of truth. Quality is at its best when the end-product matches exactly to some predefined standard – a reference-pattern, a rule-book, a design-specification or the like.

So there’s a whole industry built up around ‘quality’ in the business context. For straightforward commercial reasons, there’s a great deal of sense in amongst those impenetrable acronyms such as ISO-9000, Six Sigma, TQM and the rest – so if you’re interested in improving quality in general, you’ll find it worth exploring the reference-sites such as Wikipedia.

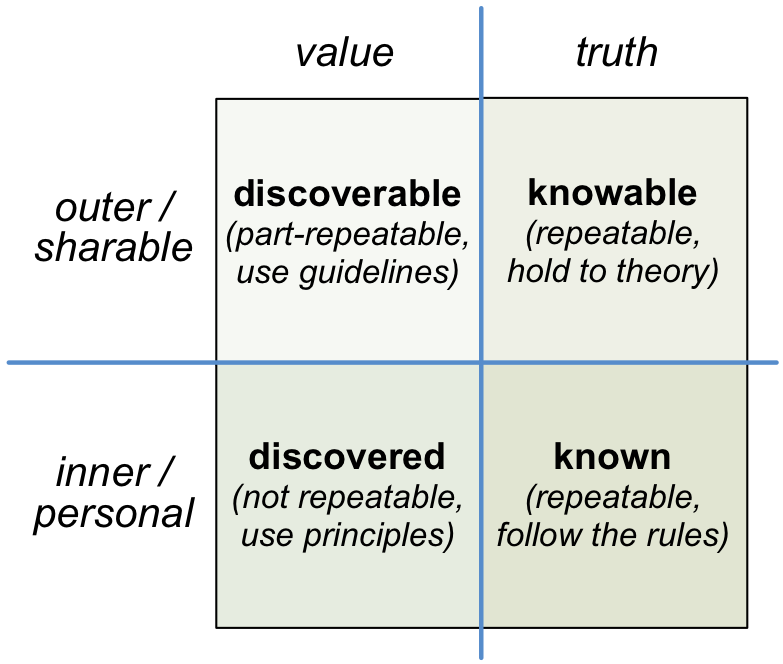

Yet in practice, quality isn’t quite as simple and straightforward as that. To illustrate this, there’s a useful model in which we partition sensemaking about quality into four domains or modes or ‘ways of working’: known, knowable, discoverable, and discovered.

Sensemaking modes

Over the next few chapters we’ll see how this kind of model applies to the disciplines of dowsing. For now, though, let’s continue exploring that notion of ‘quality’: what is it, exactly?

Predictable quality

In principle at least, that kind of quality that we see in business (sometimes described as ‘objective’ quality, though it’s actually a bit of a misnomer) should be the exact same for everyone. It expects its world to be certain, known – based on clear rules, clear patterns of cause and effect. There are procedures, work-instructions, the fast-food franchise handbook that describes ‘the one right way’ to mop the floor. Deviation from the standard is anathema: there’s no time or tolerance for anything more than training, no place for skill or personal difference. Following the rules assures a quality result; and the rules alone will suffice.

When the world becomes too complicated for that, we move on to analysis, the domain of the knowable. But there’s still always an assumption of certainty and control, that there will always be some true standard against which quality can be confirmed. So it’s here that we’ll find a focus on facts, on statistical analysis of results.

Here too we’ll see a detailed exploration of ‘best practice’ in every possible work-context - leading to outcomes that we might describe more as discoverable than ‘knowable’. Unlike the procedure-manuals, the idea of best-practice and the like does at least acknowledge that the world could perhaps be different in different places and for different people. It doesn’t assume there’s only one ‘right way to do it’: instead, it describes what’s been known to work well elsewhere, and provide some guidance as to how to adapt it to the local conditions. Which is a lot more helpful, really.

But it still doesn’t make much allowance for uncertainty, or the kind of ‘one-off’ contexts which we find ourselves dealing with so often in dowsing - those moments that are more discovered than ‘known’. For those, we need to consider more than just ‘objective’ quality: we also need to understand and maintain an appropriate balance with the subjective side of quality.

Subjective quality

As soon as we introduce skill – in fact as soon as we introduce a real person – there has to be a subjective or personal side to quality. What’s true for me – my understanding of what is quality, and what is not - may well not be true for you, and vice versa. Quality exists, quality is real, but we can’t define what it is: there’s no fixed standard against which to measure.

Instead of ‘truth’, the measure of quality here is value – what it means, how it feels, in a personal sense. There is still a kind of truth, though, that comes from respect for the material, the context itself, as typified in Michelangelo’s comment about ‘to free the sculpture from within the stone’.

There’s also a need for commitment to the skill ‘for its own sake’. Good workmanship shows good quality, clear evidence of what Robert Pirsig, in his classic Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, described as ‘gumption’. We may not be able to define beforehand what the end-result will be, yet we have a clear idea of what it would look like – and even more of what it won’t. The end-result may be finely-polished, perhaps, the work of months or years, or it may be rough-hewn, simple, assembled in a matter of moments; yet the quality – or lack of it – will usually be evident for all to see, or feel. In that sense, qualitative value both has and is its own truth.

So called ‘objective’ quality expects its world to be certain, to be repeatable, and repeatable by anyone. Subjective quality doesn’t: instead, it accepts that its world is acausal, complex, chaotic – in a word, messy. There may well be some kind of ‘self-similarity’, but nothing is ever quite the same. Yet even if there are no certainties, no fixed rules to follow, quality still exists: we don’t simply throw our hands up in the air and say “anything goes”. In the discoverable sensemaking-domain, where things still have a semblance of repeatability, we can hold to proven guidelines and ‘rules of thumb’; and in the discovered domain, the domain of ‘the unknown’, where things aren’t repeatable at all, we turn to principles that have stood the test of time – such as an awareness of the different layers in the skills-labyrinth. It works.

What also works is a different kind of sharing. Where the complicated, ‘knowable’ end of objective quality relies on supposed certainties, those who deal with worlds that are inherently uncertain – maintenance engineers, for example – will turn to ‘worst-practice’, stories about what didn’t work, and the experiments they went through to fix it. There’s also more emphasis on ‘communities of practice’, to help that sharing of stories, and assist newcomers in making sense of what’s going on in their personal quest for quality.

Quality in practice

So what does all of this mean for the disciplines of dowsing, and for other subjective skills?

The first answer is that all of the above applies: we’re always dealing with all those kinds of quality, objective and subjective, personal and sharable. Because dowsing is a personal skill, subjective quality will tend to come to the fore; but the moment we want to do anything with our results, we’d better be sure that the objective facts are there too.

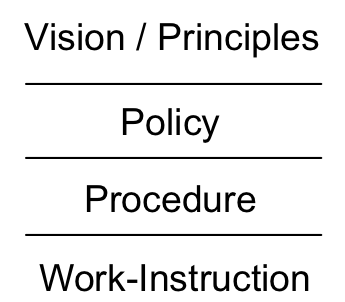

So how do we do that? One tactic is to use the same layered approach as in business quality-management:

- principles – the overall ‘guiding star’ for all of the work

- policies – ‘approaches’, decisions about how we approach changes to the work

- procedures – ‘mechanics’, decisions about how we think about the work, how we change what we do and how we do it

- work-instructions – ‘methods’, decisions about how we do the work.

Our starting point is the ‘product’ of the work – which in the case of dowsing is an opinion, about a desired or identified coincidence of what is looked for and where we are. We then use those opinions as appropriate, according to the context, but those opinions or judgements are at the core of what we do.

Layers of quality-management

In practice, we run the quality-management sequence backwards. We start from the work-instructions – for which the dowsing equivalents are things like ‘hold the rods this way’, ‘mark your location this way’, ‘use this kind of sample for this purpose’, and so on. That gives us something repeatable, a known reference-point, which will be drawn from some kind of best-practice – either from someone else, or our own.

When that work-instruction doesn’t fit any more, or doesn’t seem to work well, we move upward to the procedure, to create a new work-instruction. This is where we need that information about mechanical criteria for the instrument; likewise the more subtle ‘mechanics’ about thinking-processes and the like. We use these to assess the context, and guide a design for another way of working.

When the context changes so much that this doesn’t work either, the standard says that we need to move upward again to policy. In a dowsing sense, this is where we shift from ‘objective’ to subjective: not so much about what we do, as the way in which we approach what we do, how we make our decisions, and so on.

When appropriate care in all of this still doesn’t give us the results we need, we move all the way up to vision and principle – the final ‘guiding stars’ for everything we do. This is where that ‘equation of need’ comes in, for example: hence one useful principle in dowsing is a cultivated selflessness – “take of the fruit for others, or forebear”.

Yet this also takes us back full circle, because the ultimate root of dowsing is in precision of feeling. What exactly do we feel, at each place, at each moment, at each potential co-incidence? The instrument’s responses may be the only visible part of what we do; yet the instrument itself is just a way to externalise feelings – angle-rods as crutches for a limping intuition, if you like.

So the ‘guiding stars’ for quality in dowsing are those four principles we saw earlier:

- precision in sensing

- precision in identifying locations and facts

- precision in deriving meaning from coincide-ence of sensing and location

- precision in use of meaning – which also includes ethics.

Ultimately, what use is it? How do we identify quality in that use? For each of these, the answer lies in discipline – the four disciplines of the disciplined dowser.

The disciplined dowser

If an emphasis on quality is bad enough, talking about discipline may well sound worse. Memories of primary-school, of standing in the corner, “not enough discipline” and all that…

Don’t worry – it’s not like that! (Well, maybe a little bit, we could say with a grin… But at least here we do explain what discipline is, why it’s a useful habit to develop – for your benefit, that is – and how to develop it. Which is more than they gave you at school, we’d guess?)

In itself, there’s nothing difficult in discipline. It’s very simple: it’s about developing a habit to plan and prepare for the work we intend to do; to notice what we do, and what we’re thinking whilst we’re doing it; to check whether these are in accord with what we’ve chosen to do; and take action as appropriate to change any of these if there are any concerns with quality.

What complicates it a little in dowsing is that there are four distinct strands or modes or ‘disciplines’ that we need to keep track of within the overall discipline. We need to understand what these modes are, what we can and can’t do within each, and how and when and why to switch between them.

Remember our earlier summary of dowsing, that it’s about sensing at an identifiable location to derive information that’s meaningful and useful. The information comes from our sensing of a co-incide-ence between what we’re looking for and where we are, and it may be a quality (a direction, a ‘feel’) or a quantity (a number, a count, or a simple yes-or-no). So the four disciplines are these:

- sensing – the dowser as artist

- define what we’re looking for, identify where we are – the dowser as scientist

- derive meaning – the dowser as mystic

- derive usefulness – the dowser as magician

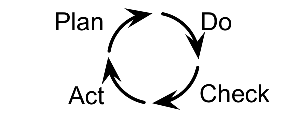

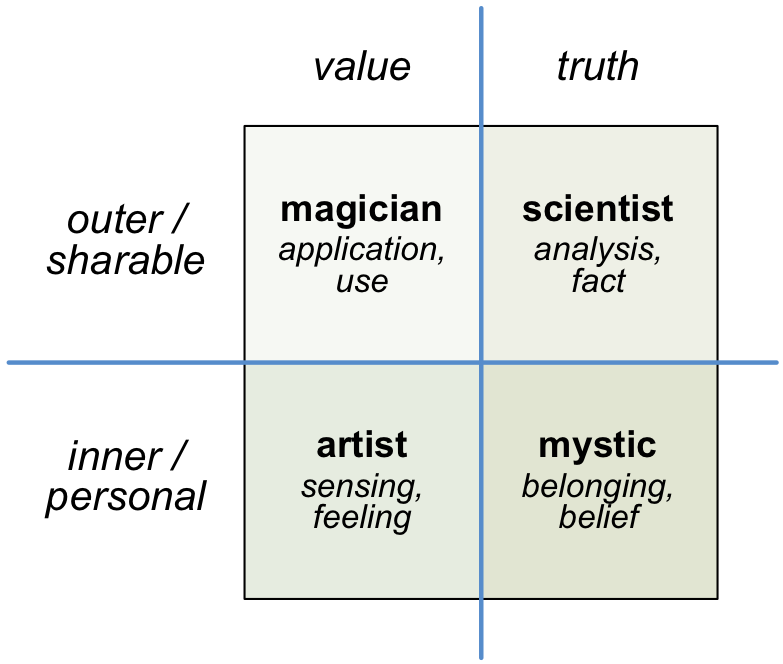

As for why we emphasise just these four modes, it’s probably simplest to explain with a diagram:

The four disciplines

In effect, this is a not-quite-arbitrary split of the world of dowsing-work across two dimensions:

- subjective <-> objective, or personal <-> shared / common

- value <-> truth, or qualitative <-> quantitative

This gives us four distinct modes: subjective value, subjective truth, objective truth, objective value. Each mode or discipline provides its own distinctive view into the whole, and also has distinct tactics that we would use within that mode – though only within that mode.

So for example, the discipline that we’re calling ‘dowser as artist’ is all about subjective value, those aspects of dowsing that are strictly personal, that belong to self alone – about the ways we sense and experience our various impressions of the site and its context. When we place our focus on that ‘artist’ mode, we pay careful attention to what we feel at each place, how we feel, what we sense, how we could portray what we sense, and so on, as well as the responses of any dowsing-instrument we might be using at the time.

What we don’t allow when we’re in that Artist mode is any intrusion from beliefs and expectations (from the Mystic, subjective truth), from matters of measurement and the like (the Scientist, objective truth), or from concerns about the end-purpose (the Magician, objective value). Each of those other modes is certainly relevant, and we need to pay our full attention to them all within the dowsing practice – but not at the same time.

At each moment, we’re in just one mode, using just one type of discipline; and to make sense of the whole, we move between the modes, cleanly, consciously, explicitly, moment by moment. There are paths between modes that are mutually supportive, such as Artist -> Magician -> Scientist -> Mystic, the dowser’s equivalent of the classic sequence ‘idea -> hypothesis -> theory -> law’ that’s so important in the sciences. Each mode is distinct, and some can be mutually antagonistic, particularly Artist <-> Scientist, or Mystic <-> Magician. And we also need to take care not to get stuck in one or two preferred modes, but maintain a balance between them all. So there’s also an implied fifth discipline about the process of switching disciplines – an integration that unites all these different views into the single overall discipline of dowsing.

It’s likely, then, that the single most important factor for quality in dowsing is understanding which mode we’re in at any given time, and working appropriately to match the constraints of that mode. And if our work is to be meaningful and useful to others, we also need to know how to present our results in ways that are appropriate to the respective mode: we don’t present ideas as facts, or vice versa.

So let’s look at each of these disciplines in more detail.

Seven sins of dubious discipline

Before we can put all this into practice, there are a bunch of problems that really must be faced. We’re aware that we might be a bit unpopular with some folks for saying this, because a few deeply-cherished delusions may get trodden on in the process. But fact is that if we dowsers don’t face those delusions… well, to be blunt, there won’t be any point in anything that’s done in dowsing. Yes, it really is that bad. Seriously.

The problems range across the full range of quality-issues we’ve seen earlier, but for convenience, we’ve clustered them here into what might be called the Seven Sins of Dubious Discipline.

The hype hubris

Sin #1 arises from what we might, in our more polite moments, describe as a triumph of marketing over technical expertise. (There are some other epithets for this that are rather ruder, if often rather more accurate.) Dowsing, earth-mysteries, in fact pretty much every field of study with a strong subjective element, are all plagued by a relentless pursuit of hyped-up glamour – Egypt! Atlantis! the Golden Age! – in which style takes priority over substance. “Never mind the quality, feel the width!”, to quote the tag-line from an old TV comedy…

Glamour sells, but it isn’t real. Like junk-food advertising, it promises sustenance, but never really delivers, leaving us unsatisfied and wanting more. Yet because the hype seems to be all that’s on offer – or at least all that’s easily available – we can get sucked back into it, again and again. More to the point, we trick ourselves into falling for it, time after time after time. And it’s our responsibility to learn to not do so – to recognise the hype for what it is, and move on.

Fair enough, the hype and the glamour are often the ‘hooks’ that grab our attention in the first place, gaining our interest enough to get us started. But at some point – and preferably sooner rather than later – we need to wean ourselves off the pre-digested junk-food, and get down to the real meat of the matter.

It’s not just the quality of our own work that’s at risk here, because there’s also a darker side to this. It’s not only that those who do the ‘boring’ detail-work, often for decades, have no way to publish their results: we’ve seen all too many cases where they’ve been misused, plagiarised, derided, then ignored, in a subtle yet singularly nasty form of ‘life-theft’. When rip-off artists are rewarded handsomely for taking us all for a ride, whilst ‘the little people’ who’ve been stolen from are actively penalised, there’s no incentive to do real work. When hype is allowed to masquerade as reality, quality suffers, for everyone.

In short, to use the old advertising metaphor, the sizzle ain’t the sausage: the hype can sometimes have a useful role to play, but in itself it isn’t real. So when someone tries to sell you the sizzle, look for the sausage: if the substance isn’t there, it’s time to walk away.

Arises from:

- blurring between Artist exuberance and Mystic belief / belonging

Resolve by:

- go to Scientist mode to check facts and sources

- cross-check in Magician mode by questing and testing usefulness of the ideas and assertions

The Golden-Age game

Sin #2 has its source in what we might call ‘a bizarre blend of super-science and super-religion’. The idea is that somewhere in the distant past – you pick when and where, there’s plenty to choose from – there was just one culture, one civilisation, one faith or whatever, with a special elite class of priest-scientists, separate from mere ordinary mortals, who somehow ‘knew it all’. They’d created the perfect utopia, which is ready and waiting for us now, if only we can find the way…

It’s a lovely dream, perhaps. Yet that’s all it is: a lovely dream. And in most cases its hidden purpose is to distract attention from our real responsibilities in the here-and-now. Which is why, if we’re not careful, chasing that dream can become a serious sin…

There’s no doubt that there is value in the quest for the ‘Golden Age’. The hope that there can even be such a place – either in the outer world, or within ourselves – is a crucial, essential driver for personal and social change. Yet we need to balance that quest with realism, and with a great deal more honesty and self-honesty than the hype-ridden hagiography of this field will usually allow.

What’s going on here is indeed about ‘super-science and super-religion’ – or more accurately a muddled blurring between the modes of the Scientist and the Mystic. The latter needs, above all, to believe in something, deeply, passionately: that’s its role. The Scientist needs concrete facts: that’s its role, too. But in the Golden Age Game, beliefs are treated as fact, and facts are filtered to fit in with the assumptions of the belief. Neither mode is used correctly; and whenever any kind of challenge occurs in one mode, the game jumps across to the other mode whilst still purporting to use the first mode’s rules. It is fact because I believe it to be true; since it is fact, it is therefore true, hence must be believed by all. Round and round the garden we go: no checks, no balances, no questions – and no question of usefulness, either. And behind it, all too often, a subtle unacknowledged arrogance: we followers of the Golden Age are also, by definition, members of that special elite, the ‘Chosen Ones’, whilst all other ‘unbelievers’ are not…

When we do check those claims against real-world analogues, such as Australian aboriginals, or the Amazonian peoples, it’s true we do often find a deep knowledge that can be far outside of what’s known in mainstream ‘techno-scientific’ culture – which is why drug-companies and others fund expeditions to raid and, bluntly, steal as much of that knowledge as they can. Yet that knowledge is also highly contextual – in other words, it lives as much in the Magician mode as the Scientist or Mystic – and always derives in part from the personal experience of the Artist mode. And though the respective lore may well have been passed down through an unbroken line of elders or grandmothers – who may well guard that knowledge with care, for reasons of health and safety if nothing else - there’s no real evidence for anything resembling the Golden Age’s beloved priesthood-elites. Just ordinary people, living their lives in their own particular way, with their own particular, peculiar responsibilities. Just like us, in fact.

The ‘truths’ of the Scientist and Mystic have no meaning on their own – and especially not when they’re mangled in Golden Age myths. To reach anything that anyone can use, they need to be balanced with the Magician’s awareness of appropriateness. And as dowsers we can also use the Artist mode to find more from the landscape than could be learned from a half-imaginary translation of some half-invented ‘ancient scroll’.

So whilst no dowser would doubt that there are real mysteries yet to be explored, the Golden-Age Game distracts from that deeper exploration. Its purported marvels consist of little more than a handful of mysteries taken far out of their real context, contorted by clueless ‘cultural imperialism’, narcissistic nostalgia and self-centred delusions of grandeur, and blown up out of all proportion by wishful thinking, hype and hope.

More than hope, perhaps. There’s a Welsh word ‘hiraedd’ that describes this well: woefully mistranslated as ‘homesickness’, it’s more “a longing and grieving for that which is not, has never been and can never be”. We do need to respect that grief: when we look deeply into it, it hurts more than most can bear. Yet building Golden-Age myths to hide from the hurt just does not help. Take that alone-ness, that crushing sadness, and work with it to build something real instead.

There is nowhere else, no-when else to which we can run away from the perils and problems of the present. If it can be said to exist at all, the only possible Golden Age we can experience exists in what we create, here, and now

Arises from:

- blurring between Mystic mode (belief, and desire for sense of belonging to something ‘special and different’) and Scientist mode (beliefs mistaken for facts)

Resolve by:

- maintain clear distinction between Mystic and Scientist

- balance with Magician and Artist modes to establish context, meaning and use

The newage nuisance

Sin #3 is perhaps more subtle, yet certainly no less of a problem in practice, because where the Golden Age Game is careless in its use of the Scientist and Mystic modes, the Newage Nuisance plays fast and loose with them all…

Although it can take almost any form, in essence it’s a dilettante ‘disneyfication’ of discipline itself – a shallow over-simplification of everything, combined with a wilful, sometimes deliberate and often near-obsessive avoidance of any kind of discipline. The term ‘newage’ rhymes with ‘sewage’, ‘the discarded remnant of what was once nutritious’ – and its stench pervades pretty much every area that purports to be ‘New Age’.

Though there are some strong links with Sin #7, inadequate management of the skills-learning process (see Lost in the learning labyrinth), newage is typified by arbitrary jumps between the distinct forms of ‘truth’ in art, spirituality, science and magic. At its simplest and most forgivable level, it’ll often occur when an overdose of enthusiasm overrides sense and self-honesty – such as in the feeling of ‘instant mastery’ after the classic New Age-style one-weekend-workshop.

The excessive exuberance of ‘beginner’s luck’ is understandable, but the real problems start whenever there’s an unwillingness, or refusal, or fear, to let go of that feeling of ‘instant mastery’. So the next stage is the ‘workshop junkie’ – a ceaseless collection of just the ‘instant mastery’ level of every possible new skill, but with no depth, no commitment, and nothing to tie the skills together into anything that can be put to practical use.

Part of the problem - especially in New Age contexts with an overt emphasis on ‘spirituality’ – is that the Mystic mode is all about being, about inner-truth: it’s diametrically opposed to the Magician mode, which happens to be the only place where “what do we do with all this stuff?” comes into the picture. But the real core is that commitment to the discipline of a skill is what finally kills off beginner’s luck, and with it that initial delusion of ‘mastery’. From there on, for quite a long while, it feels like downhill all the way – and hard work too, with personal challenges that are often far harder still. An uncomfortable time, to say the least.

So there’s a natural tendency to try to avoid that discomfort by avoiding commitment, whilst still pretending – if only to self – that mastery has already been achieved. There’s then an inevitable desire to conceal – if only from self – the fact that mastery has not been reached… And the mechanism to do this is by playing mix-and-match between the modes: the rules of one mode are used to validate the ‘truths’ from another.

The simplest and perhaps most common example of this is actually nowhere near the New Age at all, but in the phrase ‘applied science’. Doing anything, using anything, places us in the Magician mode of outer-value, and must always be tested in those terms – such as ethics, appropriateness and so on. But the phrase ‘applied science’ implies that if we can call something ‘scientific’, the only test we need apply is outer-truth – which means it’s ‘value-free’. If something’s supposedly value-free, that absolves us from having to face any difficult doubts about ethics or effectiveness: so we then claim an unquestioned right to go right ahead and do whatever-it-is because it’s ‘true’. Therein lie all manner of interesting problems in the wider world…

Looking at the paths between the modes, you’ll see there’s at least a dozen different ways this game can go. For example, for dowsers and others whose work is anchored more in the subjective space, one such mistake is typified by a common misuse of the old slogan ‘the personal is political’: “this is true for me, therefore it must also apply to everyone else”, muddling the subjective space (‘personal’) with the objective space (‘political’). The only way we can resolve the Newage Nuisance is to be clear about which mode we’re in at all times, using the correct rules for that mode, and that mode alone – and also face the fears that drive us to be dishonest about what our skills really are.

The Newage Nuisance is the Golden Age Game writ large, covering the entire context of the space in which we work. Challenging it is never easy, given the emotions that such challenges will so often engender. Yet unless we do each face it firmly – not just in others, but even more in ourselves, in everything we do – that avoidance of discipline will inevitably render meaningless every scrap of work in that space.

Not exactly a trivial sin, then. One we definitely need to address…

Arises from:

- combination of incompetence and self-dishonesty in relation to any or all of the modes, and fear of responsibilities from commitment to a skill

Resolve by:

- be clear which mode we’re in at each moment, and use only the rules and tests for that specific mode

- be clear how and why we transition from mode to mode

- challenge and face the fears that would otherwise lead to evasion of the necessary discipline in each mode

The meaning mistake

Sin #4 occurs mainly in and around the Scientist mode, where we aim to establish outer-truth, otherwise known as ‘fact’. There are clear rules in this mode for deriving fact; the Meaning Mistake occurs whenever we’ve been careless with those rules, leading us to think we’ve established that ‘truth’ when we haven’t.

The simplest way to describe this is with a cooking metaphor: the end-results of our tests for meaning should be properly cooked, but if we’re not careful, they’ll end up half-baked, overcooked, or just plain inedible.

Interpretations go half-baked when we take ideas or information out of one context, and apply them to another without considering the implications of doing so. One form of this is what scientists describe as ‘induction’, or reasoning from the particular to the general – as in that misuse of the feminist slogan “the personal is political”, where we assume that whatever happens to us must also apply to everyone else. We then leap to conclusions without establishing the foundations for doing so – which can cause serious problems when we try to apply them in practice in the Magician mode.

Perhaps a better dowsing example would be the use of terms such as ‘frequency’, ‘vibration’, ‘radiation’ or ‘energy’ – each of which has a precise meaning in science, but in dowsing is often no more than a fairly loose metaphor. The catch is that as a metaphor, it has no definitions on which to anchor either itself or any cross-references. So if we then take the metaphor too literally – the ‘frequency’ of an imagined ‘vibration’, perhaps – we soon end up with something that’s meaningless to anyone else, and probably to ourselves as well. The moves towards standardised definitions in dowsing do help – such as the Earth Energies Group’s Encyclopaedia of Terms – but there’s no means to define meaningful values for frequencies and the like when the only possible standards reside in people’s heads. There doesn’t seem to be any way round this problem, either. Tricky…

Interpretations risk going overcooked whenever we skip a step in the tests, or ignore warnings from the context that we’re looking in the wrong way or at the wrong place. It’s the right overall approach – deduction, or reasoning from the general to the particular, rather than induction – but even a single missed step can soon take the reasoning so far sideways as to invalidate the lot.

Deduction works by narrowing scope, narrowing the range of choices. In formal scientific experimentation, we’re supposed to change only one parameter at a time, to ensure that we don’t accidentally skip a step and narrow the scope inappropriately. But if we don’t know what all the parameters are, it’s all too easy to change more than one as we change the conditions of the experiment. A lot more than one parameter, sometimes… And as soon as we do so, we go overcooked.

For dowsers, one essential defence against overcooking is to include an ‘Idiot’ response in the instrument’s vocabulary. By that, as we described back in Know your instrument, we mean some kind of dowsing-response that is different to those for neutral, Yes, No, or any of the directional responses, and which indicates that the dowsing-question – whatever it is – can’t be answered in any meaningful way by Yes or No or suchlike. “Un-ask the question” is what the ‘Idiot’ response really means.

To give a really simple example, how would your pendulum respond to a double-question such as “Should I go left or right?”, or a double-negative such as “Is this not the right way to go?” The pendulum’s usual yes-or-no answers can’t make any sense here – so you’ll need another kind of response to warn you of that. That type of response is also helpful in providing feedback to improve the skill in developing questions that can be answered meaningfully just by Yes or No – and as any scientist knows, the hardest part of the discipline is designing the right questions for an experiment to answer.

So if we’re not careful, we can find ourselves in the half-bakery, or with our questing overcooked. Worse, we can easily do both at once – which gives results that really are inedible. Courtesy of the Newage Nuisance, the New Age fields are riddled with it – and it doesn’t exactly help that the incompetence is then glossed over with hype (Sin #1) or some kind of golden-age myth (Sin #2). Sadly, the dowsing disciplines can be far from immune from this problem, too.

One useful hint comes from what Edward de Bono describes as his ‘First Law of Thinking’: “proof is often no more than a lack of imagination”. (There’s also a rather more forceful version which asserts that “certainty comes only from a feeble imagination”…) The problem here is that, in itself, the Scientist mode doesn’t have any imagination: it just follows the rules. So we need to be able to dive into one of the ‘value’ modes – usually the Artist, but also the Magician – to collect new ideas to play with, and bring them back for the Scientist to test. We do have to remember to distinguish between the new ideas – the imagination – and facts – the results of tests – but with care it does work well. This is just as true in the sciences, too: Beveridge’s classic The Art of Scientific Investigation talks about the use of chance, of intuition, of dreams, and the hazards and limitations of reason – “the origin of discoveries is beyond the reach of reason”, he says.

What won’t help here is the Mystic mode: in fact it can cause the Meaning Mistake, because it treats its beliefs as facts – taking them as true ‘on faith’, so to speak. Muddled ideas about ‘spirituality’ can easily lead to the Newage Nuisance; but when self-styled ‘scientists’ start treating their beliefs as fact, they end up with a bizarre, aggressive pseudo-religion called ‘scientism’ that can be a real nuisance for anyone working in the subjective space.

As with the ‘must-be mistake’, another warning-sign of potential inedibility is any use of a phrase such as “it’s obvious” or “of course it’s the same as…” – because they usually mean that a key step or test has been skipped (‘obvious’), or a simile has been mistaken for fact.

But the only true protection against the Meaning Mistake is to recognise that the Scientist mode has strict rules for meaning, to derive what it calls ‘fact’ – and we cannot be careless with those rules if we want our work to be meaningful in that mode. We can go off briefly to other modes to gather new ideas to test: but in the Scientist mode itself, there’s no middle ground – either something is fact, or it isn’t.

Arises from:

- carelessness with the rules for the Scientist mode

- blurring with the Mystic mode by treating ‘scientific’ beliefs as fact

Resolve by:

- watch carefully for keyphrases such as “of course” or “it’s obvious” or “must be”, all of which indicate a high probability of meaning-mistakes

- in dowsing, include an ‘Idiot’ or ‘un-ask the question’ response in the vocabulary to reduce the risk of overcook

The possession problem

Sin #5 is somewhat different from the others, because it doesn’t arise from mistakes with the modes as such, but from another source entirely: ego. And behind that, all too often, are unacknowledged fears that can be surprisingly hard to face…

In essence, the problem is a fear of uncertainty. When the world becomes too complex for comfort, there’s a natural tendency to cling on to what we know, what we have, what we believe, and claim exclusive ownership of all such things. In short, the problem is one of possession – but in both senses of the word, both possessing and possessed. In our context here, we see this most often in two different forms:

- possession as separation – for example, the concept of a ‘sacred site’ as something separate from the rest of the landscape

- possession as possessing ‘the truth’ – evidenced in ‘religious wars’ such as the Skeptics’ tirades against dowsers and others, or ‘mainstream’ versus ‘alternative’ approaches to healing

The first trap is that neither places nor ideas are commodities to be possessed: they simply are. And whilst a notion of stewardship does work as a model for ownership of such things, possession doesn’t: it gets in the way, all the time.

The problem stems in part from a misuse of the Mystic mode. Like the Scientist, the Mystic needs certainty in the form of what it calls ‘truth’. But whilst the Scientist gets there by testing and cross-linking everything to everything else, the Mystic simply declares something to be ‘the truth’ – hence ‘to take it on faith’. To get round the problem that some things will inevitably not fit with that ‘truth’, the Mystic mode again simply declares that anything that doesn’t fit is ‘not-true’, to be ignored. It then places an explicit yet arbitrary boundary between them: hence, for example, the arbitrary separation between the ‘sacred’ and the ‘profane’ – literally ‘pro-fanum’, ‘that which is outside the temple’.

Nothing wrong with that in itself – it’s a useful tactic, as we’ve seen. The problem comes when people think that the boundary is real, that the boundary itself is ‘the truth’ – and try to possess everything inside it. The amount of emotion unleashed against ‘heresy’ – which literally translates as nothing more serious than ‘to think different’ – gives us a rather strong clue that it’s not just about ‘truth’ here… Trying to possess the belief, people end up being possessed by it – which is not a good idea.