Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Historical Note

- The Echoes of Earlier Events

- Our Family Nest - Czernin

- The Games in Those Years

- Family in the Home Country

- Marusza Our Haven in Poland

- Homeschooling

- At the Foot of the Carpathian Mountains

- The Returns to the Nest

- In the Capital of the Nazi Reich

- Warsaw School of Economics (SGH)

- The Last Glimmers of Freedom

- After the Defeat

- Waiting for the Word

- Throwing Life’s Fate on the Pyre

- Through Burning Meadows of Blood

- Hopes and fears

- Survive in Spite of Everything

- Epilogue

- Timeline

- Additional Resources

- Acknowledgements

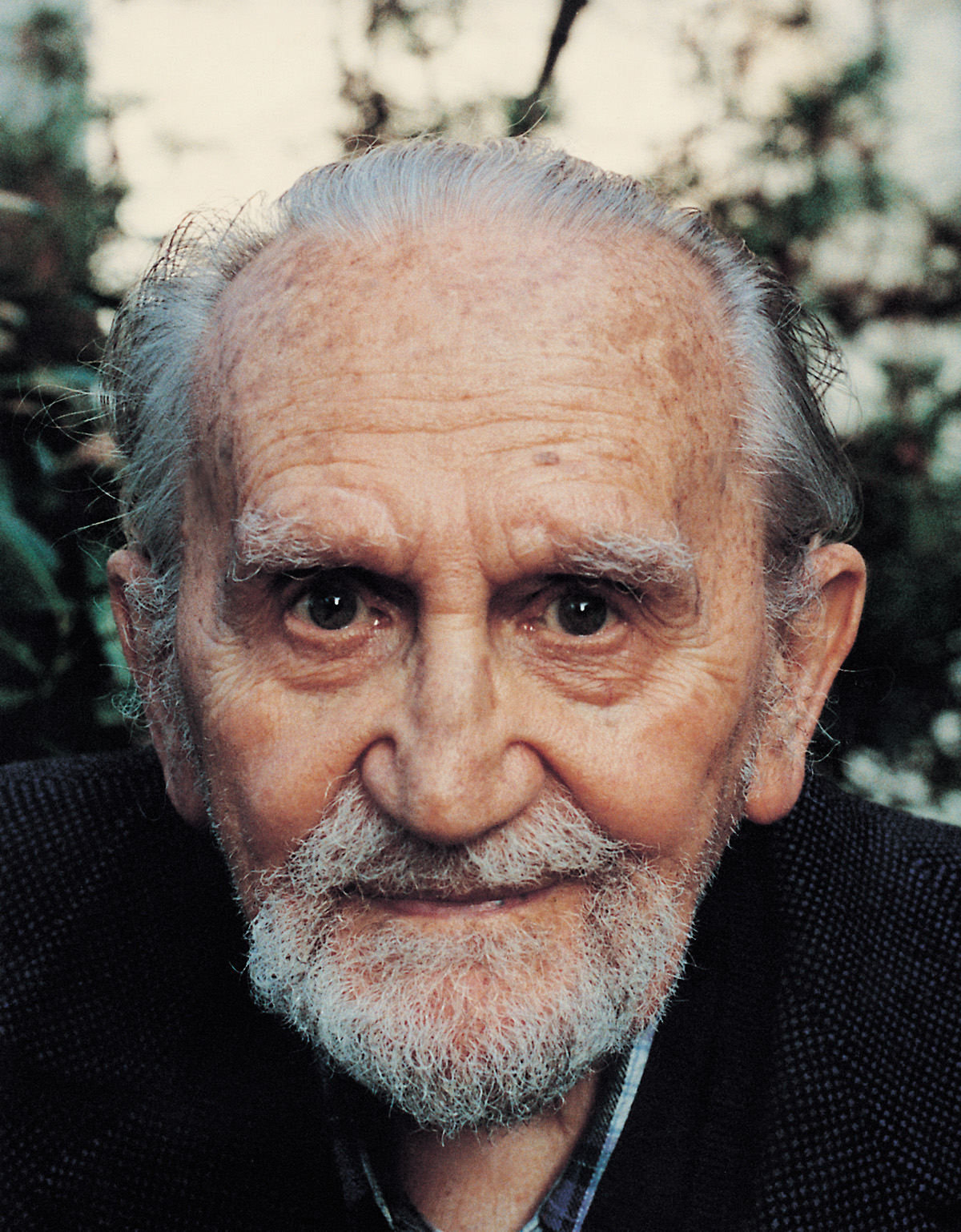

- About the Author

- Afterword

The World That Once Was…

My Twentieth Century

Halina Donimirska Szyrmer

Launch Tomorrow Publishing

Warsaw 2025

Copyright

Copyright © 2003 by Halina Donimirska-Szyrmer

Original Title (Polish): Był Taki Świat… Mój wiek dwudziesty.

Copyright © for the Polish editions 2003, 2004 and 2007, by Halina Donimirska-Szyrmerowa

Copyright © for the new Polish edition 2023, by Jacek Henryk Schirmer

Copyright © for the first English edition 2025, Lukasz Szyrmer

Translated from Polish by: Janusz M Szyrmer, Łukasz Henryk Szyrmer

All rights reserved.

The World That Once Was…My Twentieth Century

Published by LAUNCH TOMORROW

Warsaw, Poland

Copyright 2025 by LUKASZ SZYRMER. All rights reserved by LUKASZ SZYRMER and LAUNCH TOMORROW.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher/author, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. All images, logos, quotes, and trademarks included in this book are subject to use according to trademark and copyright laws of the Poland.

DONIMIRSKA SZYRMER, HALINA, Author

THE WORLD THAT ONCE WAS

HALINA DONIMIRSKA SZYRMER

ISBN:

BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Historical

HISTORY / Modern / 20th Century / Holocaust

HISTORY / Europe / Eastern

QUANTITY PURCHASES: Schools, companies, and groups may qualify for special terms in bulk. For information, email contact@launchtomorrow.com.

Introduction

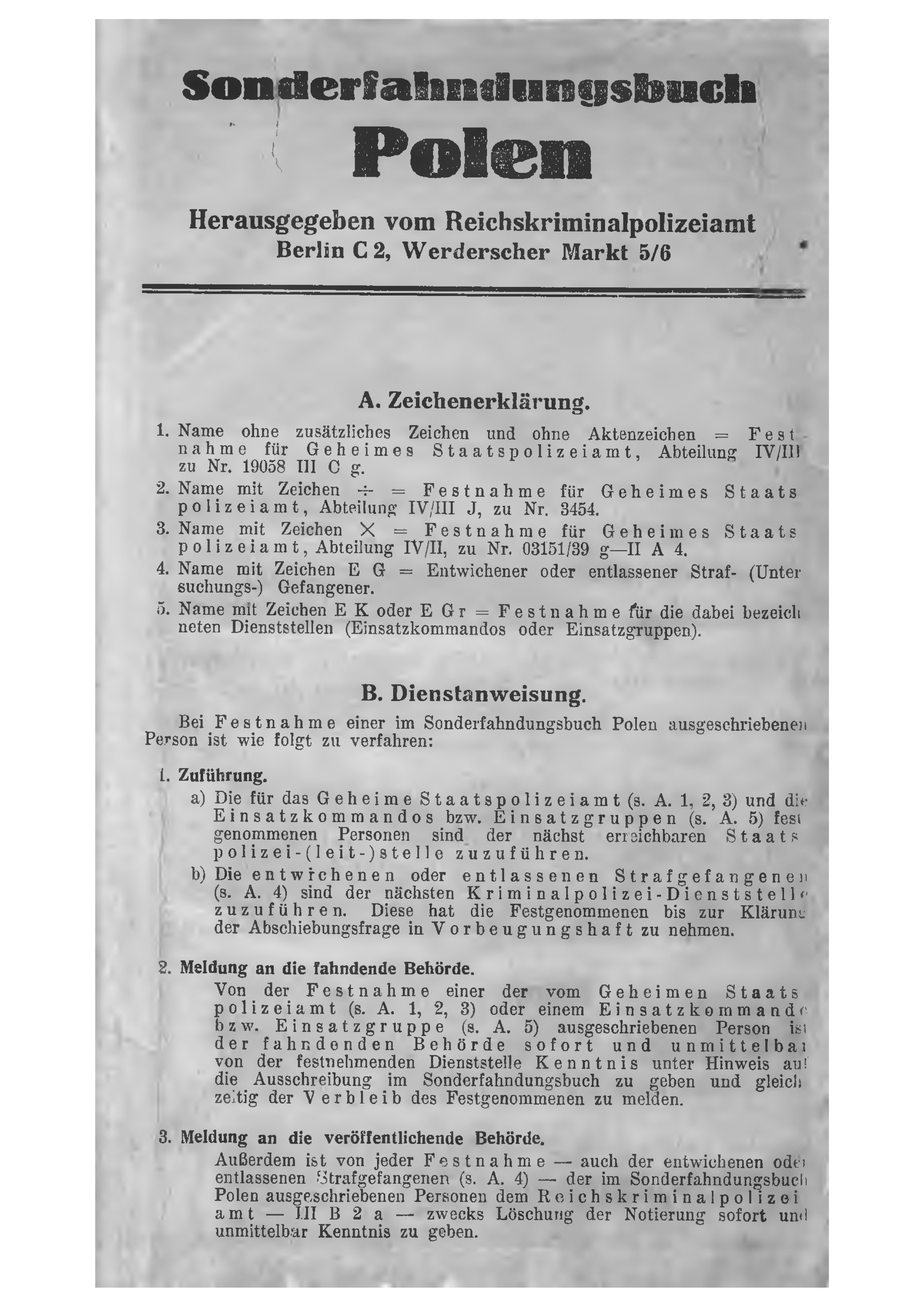

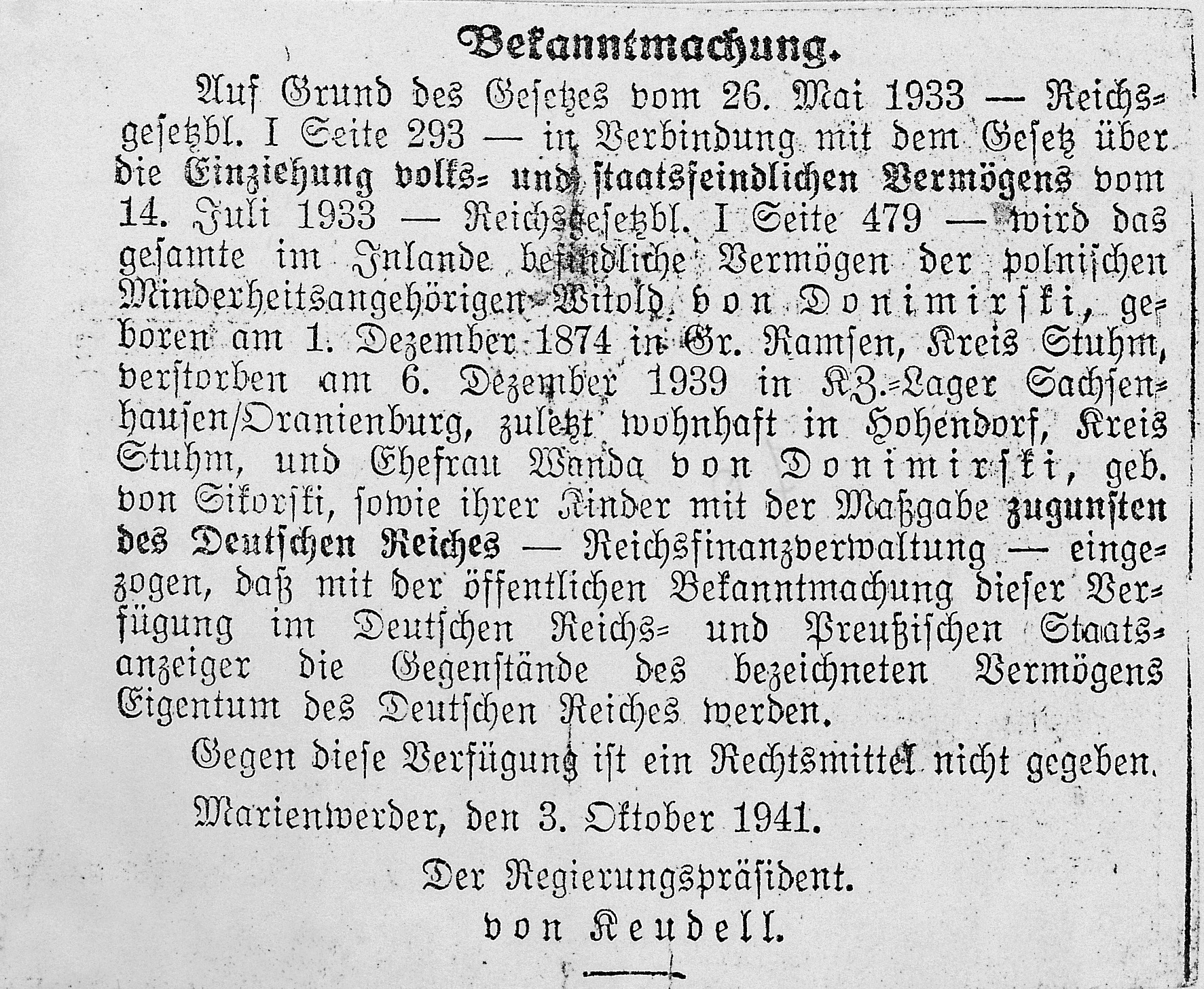

In the halls of the WWII museum in Gdansk hangs a chilling document - a pamphlet published by the Gestapo, Hitler’s secret police, just four weeks before the outbreak of World War II. Few copies of this document survived, and its existence tells a story of calculated persecution that began with a book.

In the 1930s, Polish journalist Melchior Wańkowicz published Na Tropach Smętka [On the Trail of Sorrow], a vivid chronicle of his travels through East Prussia. The book, which became a bestseller in Poland, painted an intimate portrait of Polish community life in the region, a part of Germany. Wańkowicz’s detailed accounts, including stories of his own family, unknowingly provided the Nazi regime with what they would later use as a roadmap.

As Hitler’s forces secretly prepared for their invasion of Poland, they began identifying potential resistance before their surprise attack. The SS carefully studied Wańkowicz’s work, extracting names of community organizers and influential figures from its pages. These individuals, though German citizens, were mostly of Polish descent and, despite their representation in the German parliament, had become “politically uncomfortable” to the regime.

The result was this pamphlet - essentially a blacklist - distributed quietly among senior SS officials. Those named within its pages would need to be “managed.” Later, an analogous pamphlet was released targeting politically active Poles in Poland - with the same intention.

This memoir, written by Halina Donimirska-Szyrmer, tells the backstory of the people behind those names, as they include her parents and other family members.

Meticulously fact-checked, with the intent of conveying both the facts behind what happened as well as the spirit of that time, this memoir brings the tumultuous history of Central Europe in the early 20th century to life. As the daughter of Polish landed gentry in East Prussia, Halina Donimirska-Szyrmer witnessed firsthand the rise of aggressive nationalism in Germany under the Nazis. At first glance, her account gives an intimate perspective on how Hitler’s policies impacted Poles living under German occupation, and the dangerous struggle to preserve her culture and resist Germanization. At second glance, this book delves into the after-effects of German realpolitik’s territorial ambitions.

Although East Prussia disappeared after WWII, in the early 1900s it was a German province on the Baltic Sea. Its Polish population faced intense pressure to assimilate. Prussian authorities banned the Polish language in schools and public life. Halina Donimirska-Szyrmer’s parents and the wider Donimirski clan volunteered as political activists, serving as part of the “organic work” movement. This was a form of resistance that peacefully protested Germanization. They helped establish Polish language schools, banks, cooperatives and reading rooms to strengthen and uphold the Polish community.

This activism brought the Donimirski family increased scrutiny. Hitler rose to power in the 1930s and enforced Gleichschaltung, forcing all of German society to adhere to Nazi ideology. Halina studied German in Berlin as the Nazis prepared for the 1936 Olympics, noticing how state propaganda glorified Hitler, who promoted revisionist claims that Germany was robbed of territory after World War I.

Back home, Halina’s father and wider family endured baseless character assasinations via the press. They had land seized by the Nazis and given to Polish workers who renounced their heritage and joined the party. Violence against Poles surged, seen in the destruction of a Polish school and assaults on the teacher. Halina Donimirska-Szyrmer’s account of these events provides a valuable record of the human impact of Nazification policies.

As war loomed, Halina’s parents met with the Polish ambassador in Berlin to plead for more vigorous defense of persecuted Poles in East Prussia. They warned “we personally know what we are deciding to do, and we are prepared for the worst, but our conscience does not allow us to involve in our activities so many poor people, people to whom we cannot provide assistance.” This sense of moral obligation reflects their ethos of “organic work” and non-violent cultural resistance.

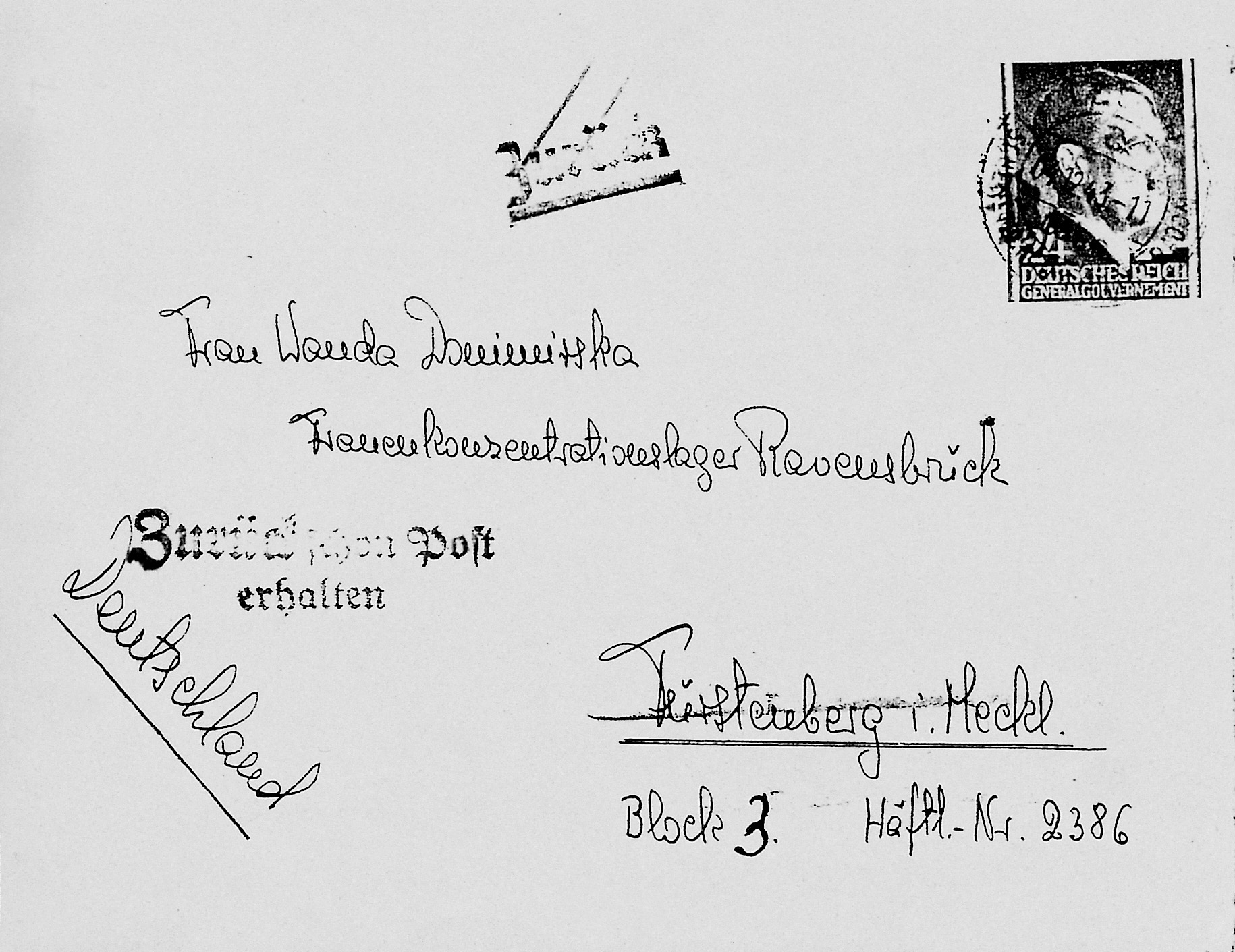

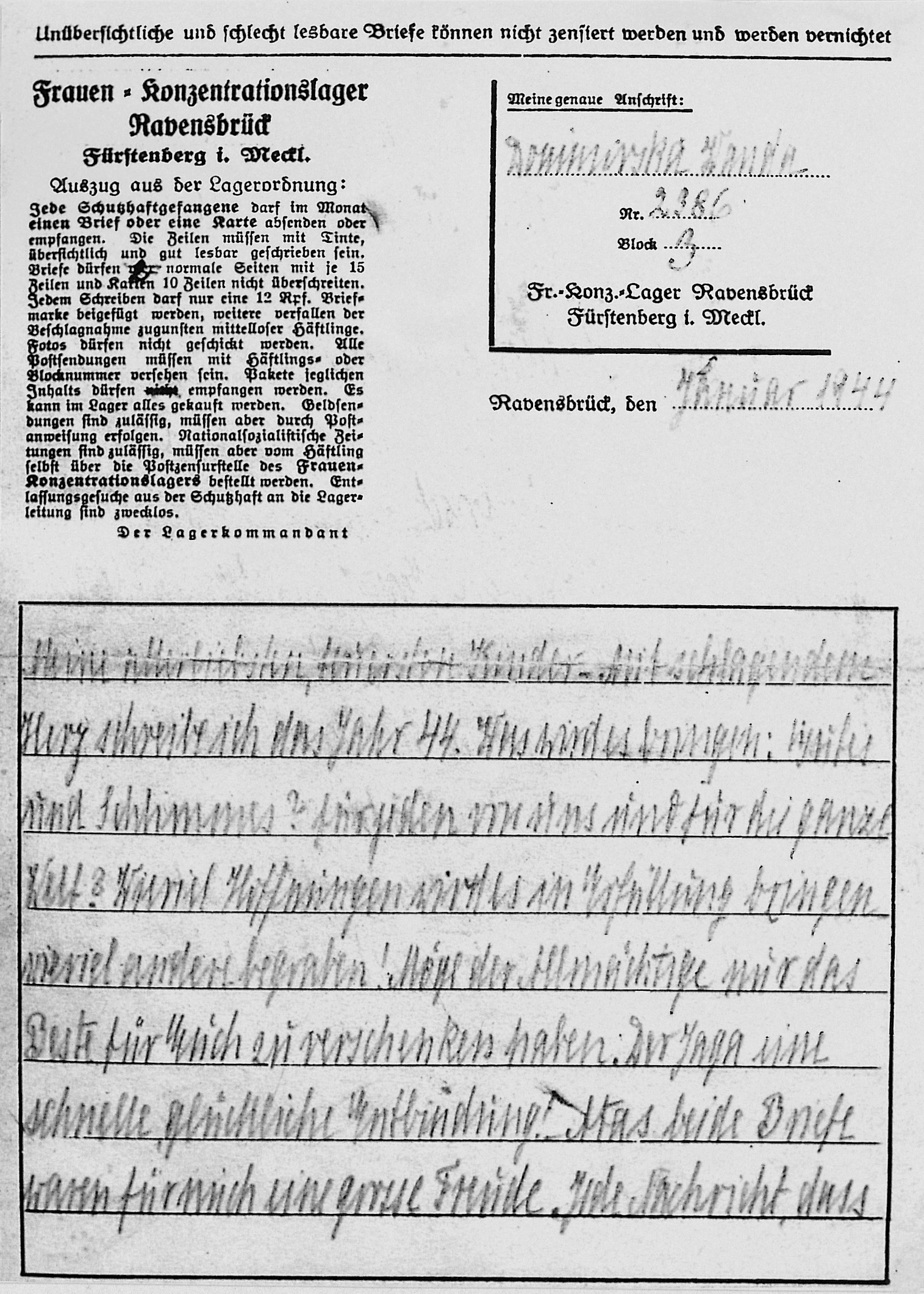

Indeed, Halina’s parents were arrested in 1939 and her father murdered in the Sachsenhausen-Orianienburg concentration camp. Her mother was one of Ravensbruck’s earliest prisoners, and survived the entire war there—leaving a deep mark on her.

During the Warsaw Uprising, Halina tended to everyone as a Red Cross nurse, including wounded German soldiers. Her criticism of anti-Semitism within Polish society leads to confrontations as university student. Many times, she demonstrates how a love for one’s country and culture can coexist with respect for other cultures.

After the war, the family lost their estate and continued serving the Polish community in East Prussia, by then incorporated into Poland.

Halina Donimirska-Szyrmer’s memoir puts a human face on the rise of nationalism and struggle for cultural survival in Central Europe in the 20th century. Seen through her eyes, the diplomatic machinations that redrew borders after World Wars I and II had profound personal consequences for Polish families like hers. Her account helps readers understand the painful experiences behind the ideological battles and geopolitical forces that shaped this tumultuous period.

Łukasz Szyrmer

Warsaw 2025

Historical Note

The following serves as a quick refresher of the relevant context, particularly for those readers who aren’t that familiar with European history.

Realpolitik, an approach to politics that emerged in late 19th century Europe, prioritized pragmatic balances of power over other concerns, including cultural identity, in a multi-ethnic Europe. It is a political philosophy focused on making the most of a given situation and operating within the context. It prioritizes cold pragmatism over any other ideology or ethical concerns, aiming to be as realistic as possible.

Otto von Bismarck was the most famous German advocate of realpolitik. He applied this philosophy to achieve Prussian dominance in Germany. Bismarck was willing to do anything to achieve his goals, including antagonizing other countries and causing wars if necessary. This philosophy allowed him to achieve his objectives, including unifying Germany, but ultimately led to conflicts with other countries, culminating in World War I.

The Treaty of Versailles, which ended WWI, was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. It ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace of Versailles exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand (the inciting incident that sparked WWI). Germany was not allowed to participate in the negotiations before signing the treaty.

The treaty required Germany to:

- disarm

- make territorial concessions

- extradite alleged war criminals

- agree to Kaiser Wilhelm being put on trial

- recognize the independence of states whose territory had previously been part of the German Empire

- and pay reparations to the Entente powers.

The most controversial provision in the treaty was: “The Allied and Associated Governments affirm and Germany accepts the responsibility of Germany and her allies for causing all the loss and damage to which the Allied and Associated Governments and their nationals have been subjected as a consequence of the war imposed upon them by the aggression of Germany and her allies.” Competing and sometimes conflicting goals among the victors led to a compromise that left no one satisfied. In particular, Germany was neither pacified nor conciliated, nor was it permanently weakened. Bitter resentment of the treaty among Germans later powered the rise of the Nazi Party.

The treaty included clauses that rearranged land and redrew borders. It parcelled out Germany’s land, given its role as the biggest player among those who lost the war. For many ethnicities including the Polish, ones that were fighting for autonomy, the treaty reversed course.

At the time, Poland hadn’t existed as a country for the previous 127 years. In practice, each region within former Germany was given the possibility of holding a plebiscite, a type of referendum, to decide their fate. This allowed a popular vote to determine whether a given area should continue being Germany or not. In particular, it gave the local population a voice in whether or not they wanted to continue living under German rule as part of the German state, or to seperate into a different country. Such a plebiscite was meant to democratically decide exactly where Germany’s borders should be redrawn. It was fair in principle. Ideally, this solution was also meant to be sustainable over a longer period. However, this approach disproportionately affected the fate of minorities.

The 1920 plebiscite in East Prussia, a pivotal event in the region’s history, was idealistically designed to determine the fate of regions with substantial Polish populations. It profoundly shaped Halina Donimirska-Szyrmer’s understanding of Polish identity and the challenges faced by her community. The sources describe the fervent activism during the plebiscite campaign, the bitter disappointment following its manipulation by the German authorities, and the lasting impact of this event on the lives of Polish families. It led to the detachment of Polish communities from the newly independent Poland. These geopolitical maneuverings had a profound impact on the lives of ordinary people, often leading to displacement, disenfranchisement, and even the suppression of minority rights. The plebiscite experience served as a stark reminder of the precariousness of minority life in German-controlled territories. It reinforced the importance of preserving Polish culture and national consciousness. This book portrays the Polish community’s unwavering determination to maintain their identity, despite facing mounting pressure to conform and assimilate.

While the book focuses on a specific historical context, its themes resonate today with concerns like identity politics, extremism, and the treatment of minority groups. As identity politics becomes increasingly prominent in various societies, it’s crucial to understand the historical context of extremist movements and the potential dangers they pose. The book’s exploration of Polish-German relations potentially serves as a cautionary tale. It underscores the importance of fostering inclusive societies that value diversity and respect the rights of all individuals, regardless of their cultural background.

The key question is: What happens when extremism flares up? And what does it mean? And what can be done, to prevent this from happening again?

The Echoes of Earlier Events

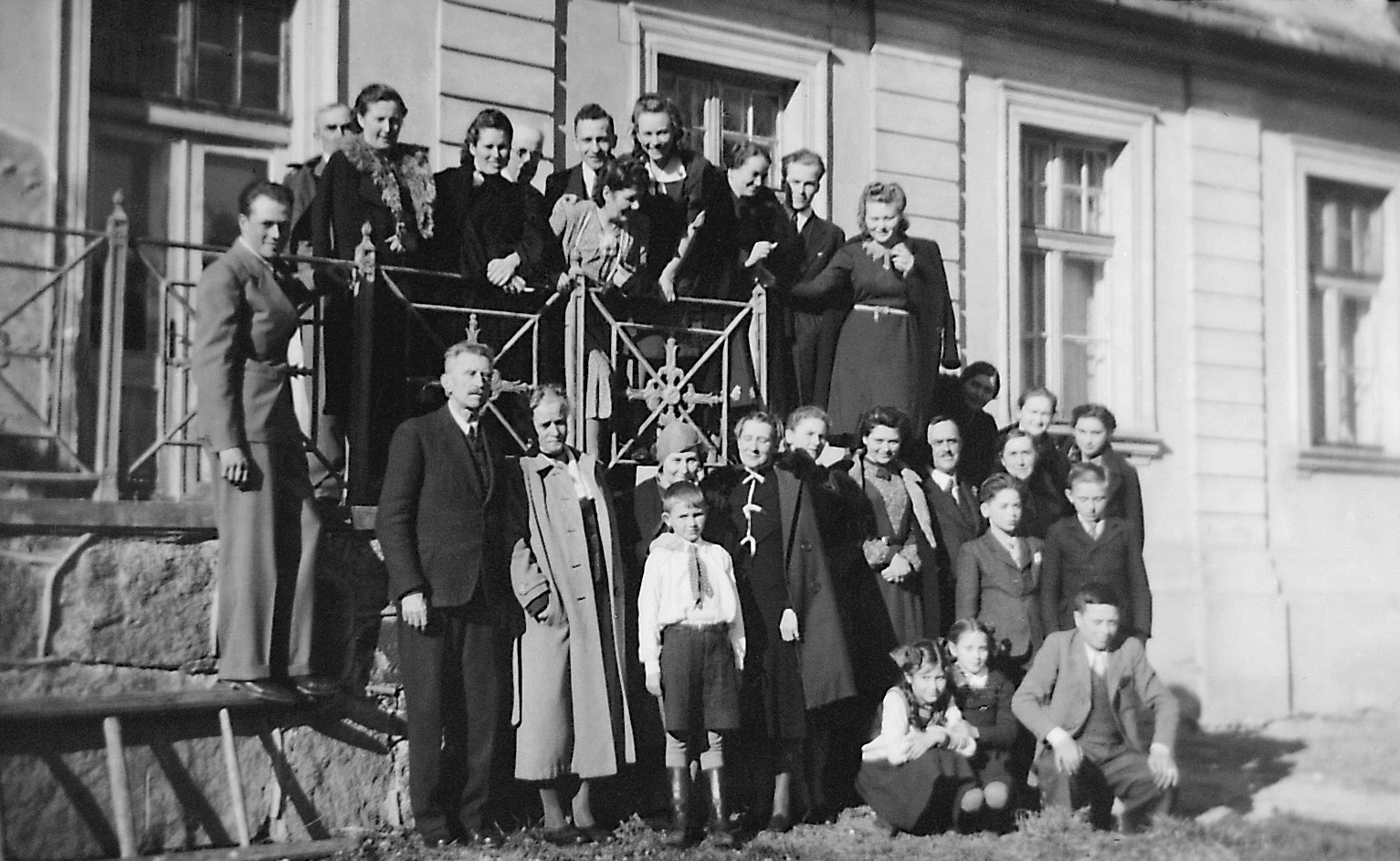

My mother, Wanda Sikorska of the Sikorski family, and my father Witold Donimirski of the Donimirski family, belonged to the Pomeranian landed gentry, descended from old Kaszubian nobility.

The Donimirski family used the Brochwicz coat of arms. Its original nest was Donimierz, located between Wejherowo and Kartuzy in the Kaszuby area of Northern Poland. In the middle of the 18th century, one of my family members, Wojciech, moved from Kaszuby to Powiśle (then the province of Malbork), where he received a lease on the Straszewo estate and took the post of a Malbork land magistrate. There he acquired the Górki estate (1768) and then the Cygusy estate (1774), effectively becoming the progenitor of the rapidly growing Donimirski family in Powiśle. In time, the family tree divided into four lines (Cygusy, Buchwald, Czernin, and Zajezierze), which survived until World War II.

As far as I know, Czernin (Hohendorf) was bought in the 1820s by my Great-Great-Grandfather Antoni. After the heirless death of his son Francis (1857), Czernin, along with the neighboring estate of Wielkie Ramzy, was taken over by the second of Antoni’s sons and my Great-Grandfather Piotr Alkantary. I was born in Czernin and spent my childhood there.

My mother’s family, the Sikorski of the Cietrzew coat of arms, hailing from Sikorzyn (North of Kościerzyna), settled in the estates of Wielkie Chełmy and Leśno in the mid-19th century. It was inherited from the Lewald-Jezierski family, located in the southern borderlands of Kaszuby, north of Chojnice. From 1887, Wielkie Chełmy belonged to my grandfather, Stanisław Sikorski, who married Anna, daughter of Ignacy Łyskowski, heir to Mileszew and a prominent defender of the Polish cause in Germany.

My parents’ wedding took place in 1910 in Brusy, as my grandfather’s estate belonged to this parish. The wedding was held in Wielkie Chełmy. As one of the participants, Roman Janta-Połczyński, recalled to me, it was very lavish and sumptuous. The party lasted for three evenings. He and the bride’s brothers constantly went to a room adjacent to the kitchen, called the “sideboard,” to fetch bottles of champagne, whole batteries of which were submerged under bales of ice. He admitted that he was among my mother’s admirers at the time.

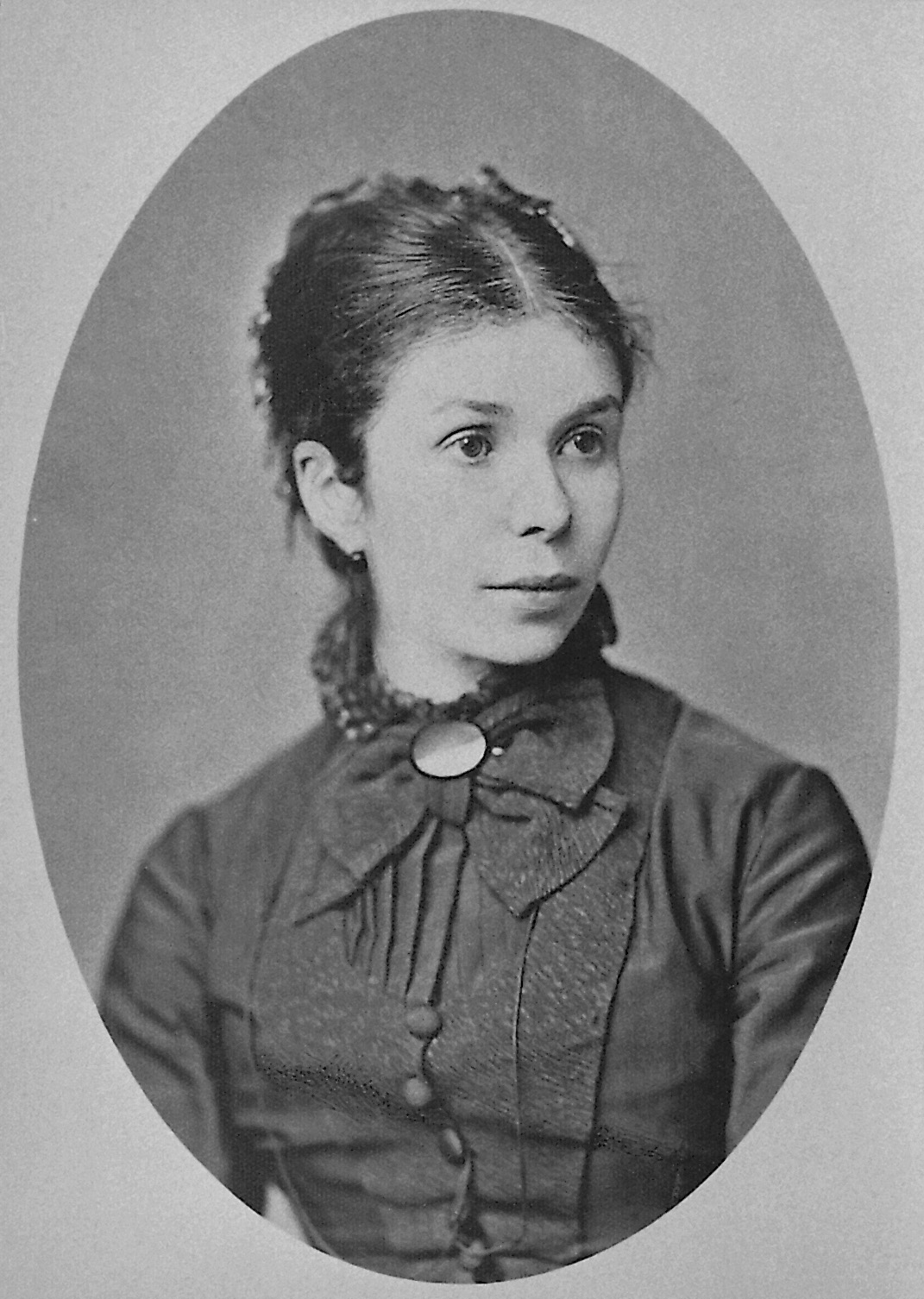

At the time of her marriage, my mother was in her twenties. She perceived the world through the eyes of an inexperienced idealist. She was a slim, tall blonde with lush light hair pinned up in a big bun. She had a lot of charm and romantic appeal. She received a careful upbringing. She graduated with honors from the Sisters of the Sacred Heart (Sacré-Coeur) boarding school in faraway Lviv (. Her grandparents placed her there, as East Prussia had no Polish schools. In Lviv, not only was Polish the language of instruction, but also Polish history and literature were taught. When she graduated from boarding school, she was sent to complete her education in Paris, where she took piano, singing and painting lessons, and learned French. Two oil still-lifes, painted by her during this period, adorned the dining room wall in Czernin.

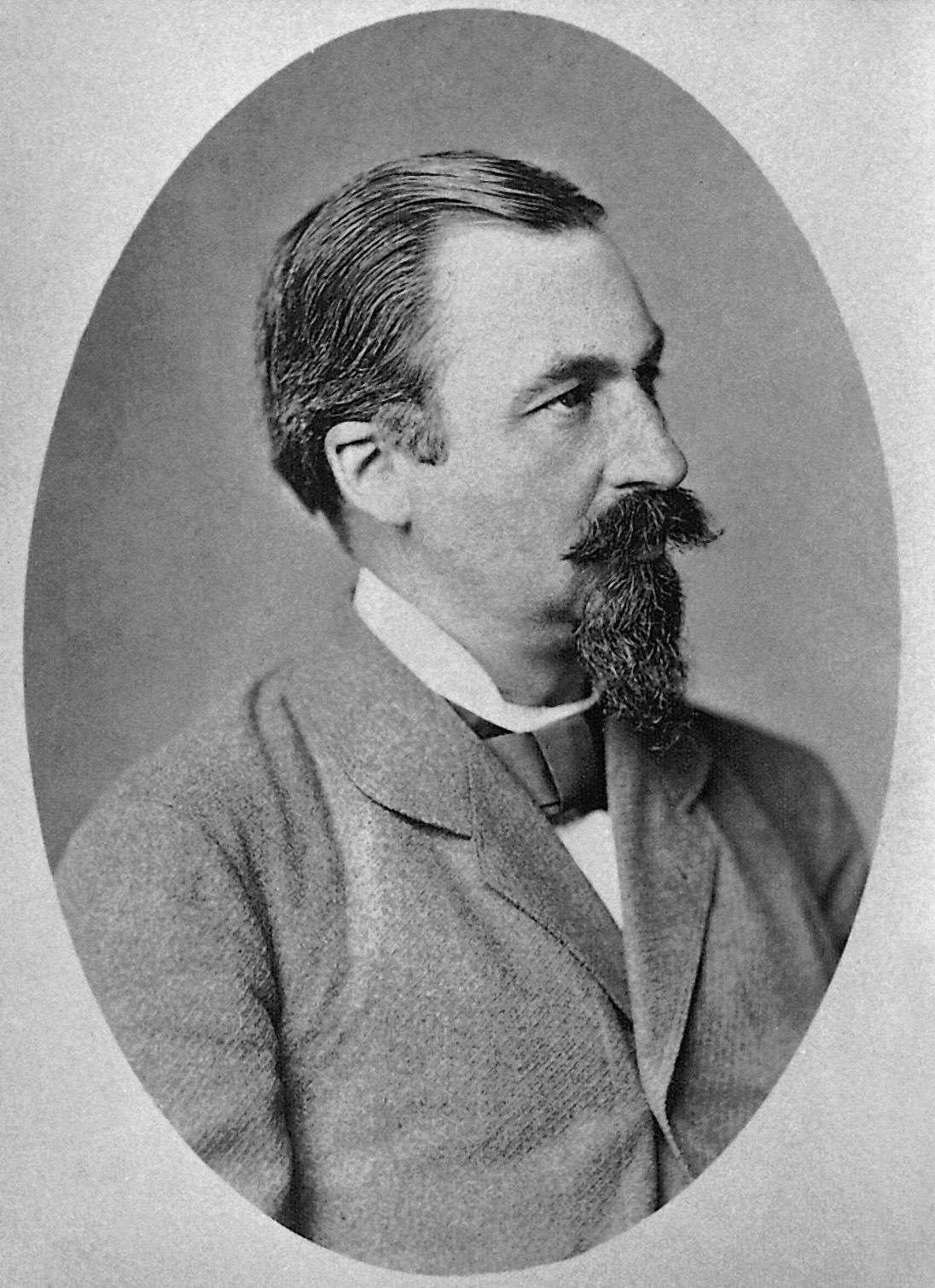

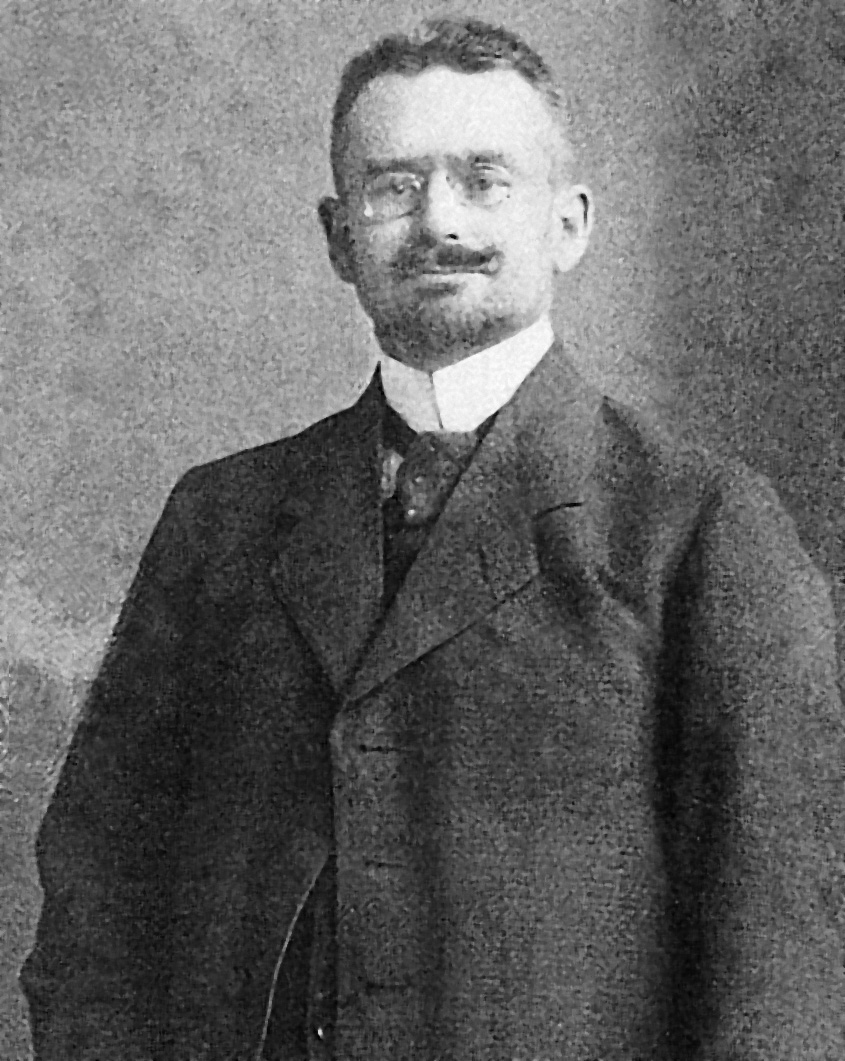

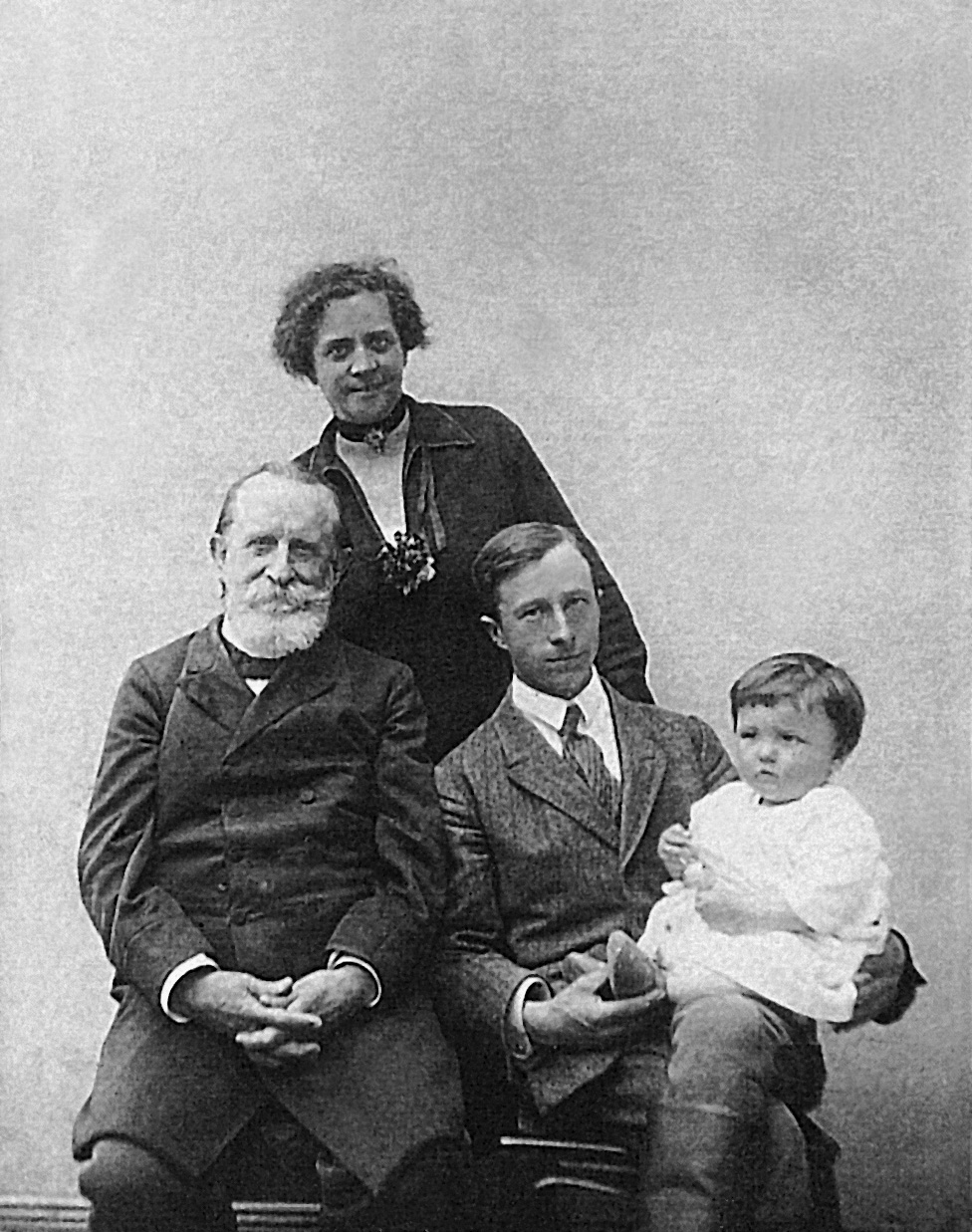

My grandparents decided to entrust the fate of their eldest daughter to a serious, upright man with a reputation as a good farmer. My father was 35 years old at the time, and was considered an old bachelor. He was born in December 1874 in Wielkie Ramzy. His parents, and my grandparents, Zygmunt and Waleria Donimirski, née Pruska, lived there in a modest manor house. Czernin, on the other hand, was the residence of my great-grandparents, Piotr Alkantary Donimirski and Bogumiła née Wolska. After my great-grandfather’s death (1887), my great-grandmother took over management of the estate, causing Czernin to fall into significant disrepair over the next following years.

Meanwhile, my grandfather, Zygmunt Donimirski, moved with his family to the Congress Kingdom, where he bought the Kożuszki estate near Sochaczew. He probably did so due to the influence of his wife, Waleria née Pruska. She wanted to live in Mazovia, closer to her relatives. Her father, and later her brother, owned the family nest there - Prusy. While still in his prime, my grandfather lost his eyesight. He died in 1903. His wife passed away soon after, in 1906, many years before I was born.

At the turn of the century, the Wielkie Ramzy estate was parceled out. Its remnants were incorporated into a manor estate in Czernin. The manor house was demolished, and only some farm buildings (including a stable) were left.

As a child, when I learned that my father was born there, I imagined that, like Jesus, he was born in a stable on hay. Some time passed before I understood what had actually happened.

My father spent his childhood bouncing between Wielkie Ramzy and Czernin. He attended junior high school in Chojnice, as did my Grandfather Stanisław Sikorski years earlier. Many boys from Polish families from Pomerania attended school there. As a group, they had a strong national consciousness, attached to their native language and culture. They secretly read Polish books and met outside the school. Most of the students were Germans. The gymnasium management severely suppressed any manifestation of being Polish. However, successive generations of young people avidly defended their national identity.

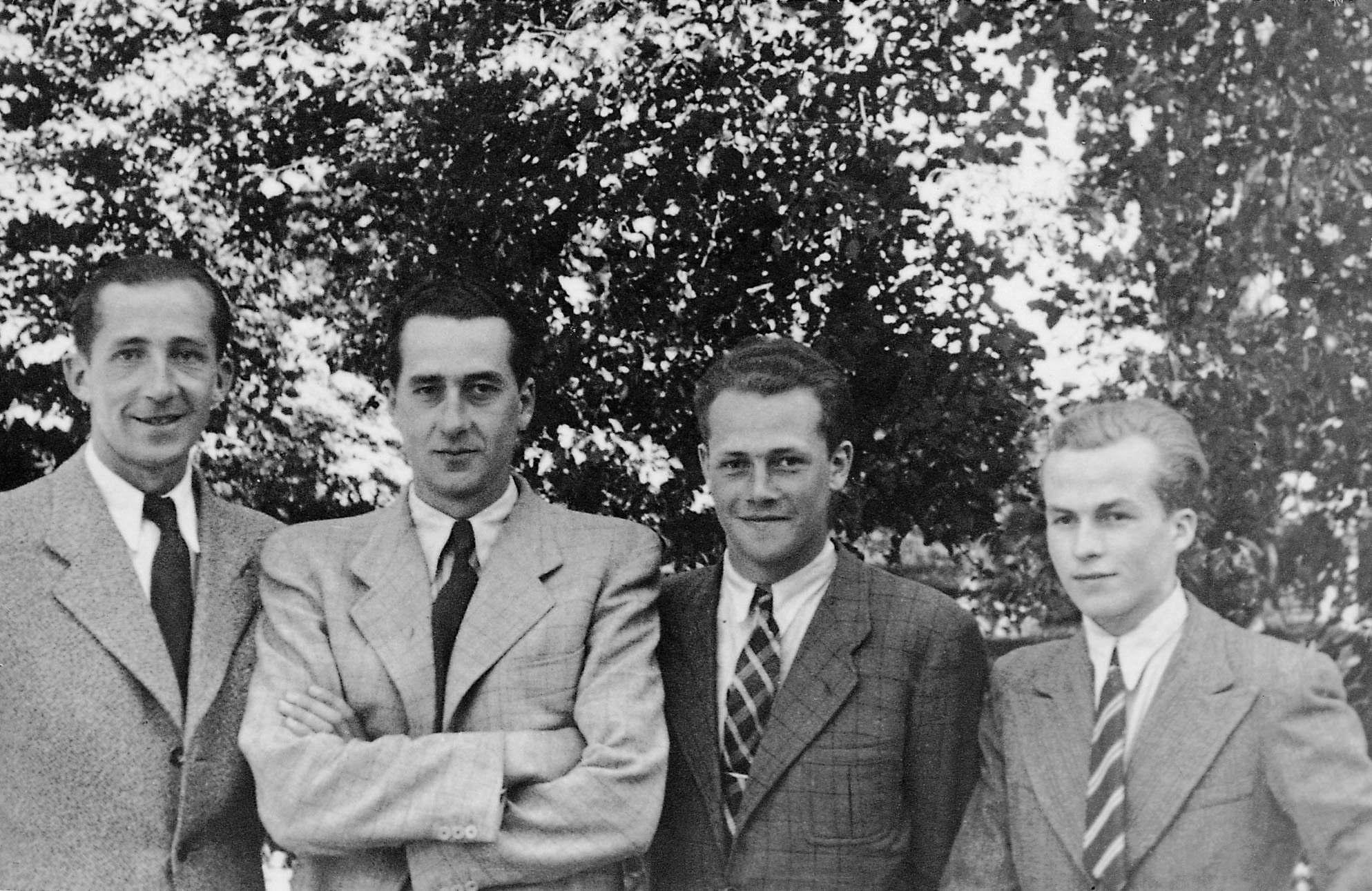

In an atmosphere of quiet stubbornness, my father graduated from gymnasium. He began college, first studying law in Berlin and then agriculture at the University of Halle. Many young fellow Poles from the Prussian partition were also studying there, with whom he became fast friends.

From my father’s stories from that era, it was clear that there was camaraderie between Polish and German students. Outside the former Polish territories, there was no hostility to Poles, compared to what the Prussian authorities had stirred up in Pomerania and Wielkopolska. Thus, there was a positive atmosphere at the University of Halle. My father retained many fond memories of this period.

After graduating, he served an agricultural apprenticeship with his Uncle Jan Donimirski in Buchwałd, and also with another uncle, Edward, in Łysomice near Toruń. In 1900, my great-grandmother, who was 84 years old at the time, entrusted him with the management of the family estate. She moved to Sztum. Despite her advanced age, she rented a spacious apartment, and maintained a lively social life. My parents often visited her. She ultimately lived to be almost a hundred years old (born in 1816 and died in 1914).

After taking over Czernin, my father set to work with great energy and enthusiasm. He rapidly produced results. Thanks to his effective management and organization skills, the estate began to generate income. It became possible to repair farm buildings, laborers’ houses, and also make some investments.

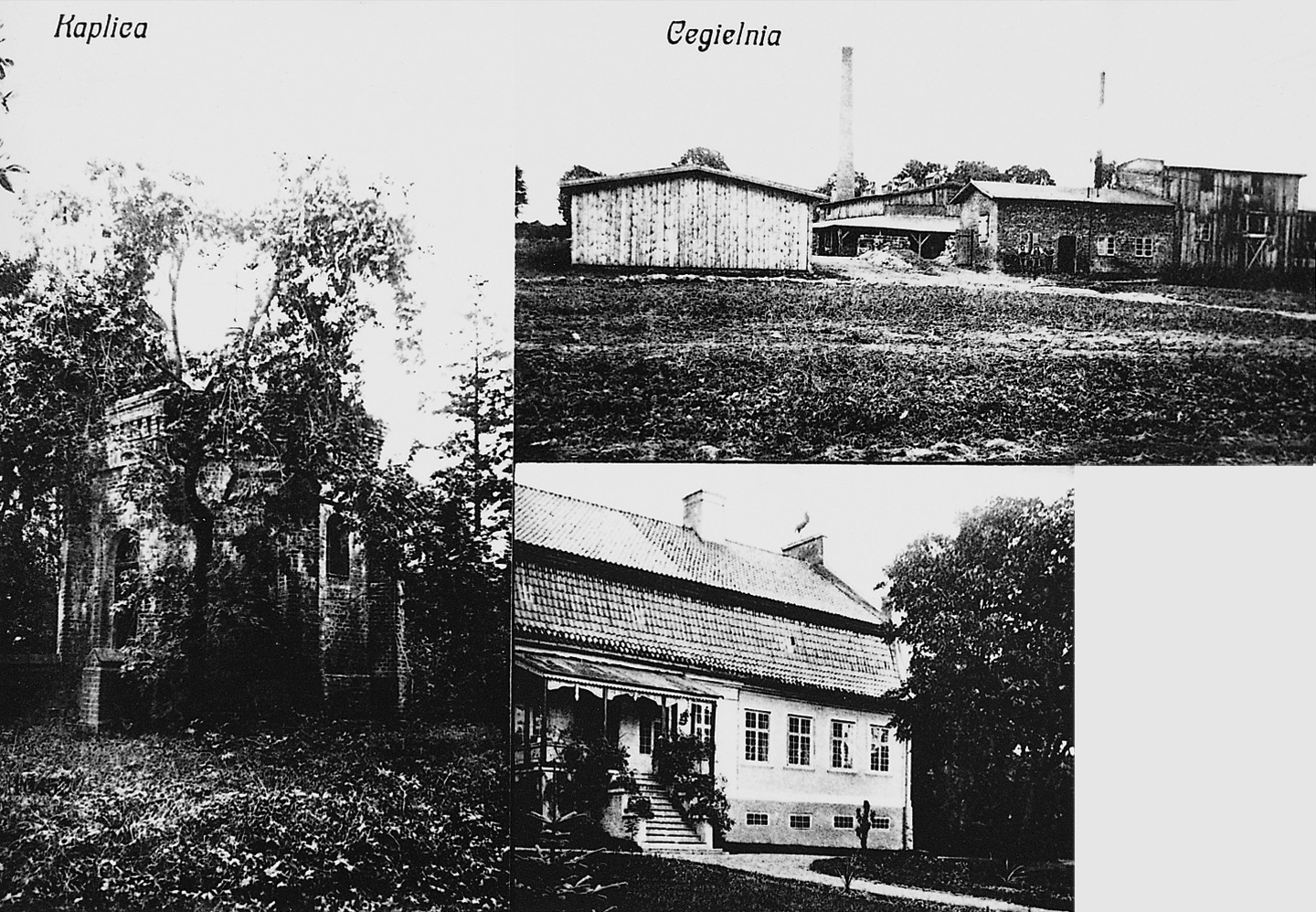

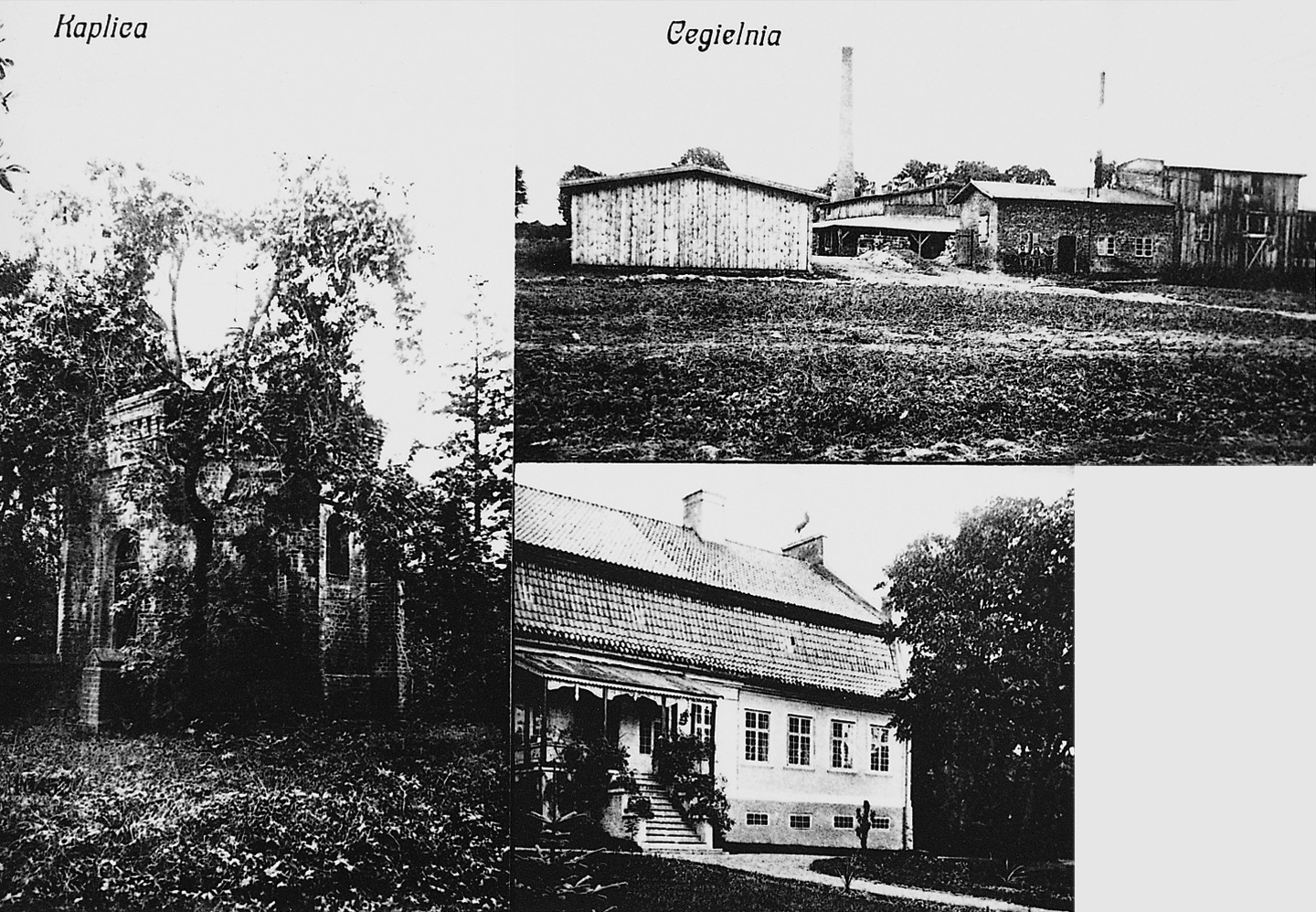

The most important of these turned out to be the establishment of a brickyard. The soil in Czernin is clay, fertile in wet years, but hard to cultivate. In times of drought, it turns into rock. This property of the soil made it appropriate as a raw material for durable and high quality bricks and tiles. Thus, the brickyard became a vital part of Czernin’s financial health. During the Great Depression in the late 1920s and early 1930s, the brickyard saved us when agricultural production became unprofitable.

After the farm recovered, my father renovated the neglected manor house in Czernin. Central heating was established, the interiors were remodeled, and hot water was brought into the bathroom from a boiler located in the kitchen above the hearth, where a fire burned all day. Comparing photos from the late 19th century and 1910, it’s hard to recognize that it’s the same mansion.

After their marriage, my parents settled in Czernin. The servants and my father’s employees gave the young couple a festive welcome. The house was decorated with wreaths, flowers, and inscriptions.

However, not everyone among the household servants was genuine, in their rush to express their joy and congratulations. Up to that point, some had taken advantage of the absence of a mistress of the house, which, of course, my father was not aware of. At first, they made it difficult for his new bride to take over the household duties. During this time, she secretly shed more than one tear. However, she managed to carry out the necessary personnel changes gently. These changes astonished my father, who had trusted and was attached to his long-serving employees. But he had even more confidence in his young wife, and remained confident throughout his life.

They were indeed a good couple. I don’t remember any disputes between them. They aligned between themselves on all important decisions. Father generally relied on mother’s opinion in such matters as our education and upbringing. In financial matters, mother relied on father. They worked on various projects together.

Both of my parents grew up in a progressive atmosphere of “organic work” 1. This was the only effective method of resisting the Germanization efforts of the Prussian government. It was practiced most in Wielkopolska, but many prominent activists also came from Pomerania. In addition to such distinguished figures as my Great-Grandfather Ignacy Łyskowski and my Grandfather Stanisław Sikorski, they included members of the Donimirski family.

My parents considered it obvious, that they should uphold this tradition. In the years of their youth, echoes of the tragic January Uprising (1864) were still strong, from which lessons were tried to be learned. The following motto guided them: “Today, our only relationship with the world - a difficult but important word: duty!”

An important part of my father’s organic work was his co-founding the People’s Bank, a savings and loan institution that supported the economic activities of Poles. My father was one of the founders of the People’s Bank in Sztum (1910) and remained one of its authorities until 1939. I remember that the bank’s affairs were a constant subject of his concern. When I was older, snippets of conversations about the bank reached my ears. The People’s Bank faced great difficulties for a long time, primarily due to a lack of liabilities. The organizers sought to strengthen them, by cooperating closely with all its branches. However, they managed to survive only by obtaining external funds, that is, from Polish banks.

Before the First World War, my father became actively involved in Towarzystwo Czytelni Ludowych (the Society of People’s Reading Rooms). He believed that the dissemination of Polish culture was an appropriate response to German propaganda about the superiority of German culture. At that time, he also served as chairman or vice-chairman of the Polish election committees for Sztum. The county put forward candidates for representatives to the Prussian parliament. He ran for such an office in the election of 1909, but the Polish list received too few votes to be elected. Upon arriving in Czernin, my mother quickly became active in social work, even though she struggled to combine it with difficult domestic and maternal duties: She gave birth to seven children in the first twelve years of her marriage.

The First World War awakened real hope for the restoration of Poland’s independence within its former borders. In 1918, a secret organization called Centralny Komitet Obywatelski (Central Civic Committee) was formed in Poznań, formed of representatives from the various provinces under the Prussian occupation. It established the Naczelna Rada Ludowa (Supreme People’s Council) soon afterwards, which officially represented the Polish minority residing in the German state. Under its leadership, regional District People’s Councils were elected by the residents. It then announced elections to the Polish Provincial Sejm (Parliament), with its seat in Poznań.

My father immediately joined these activities. He was a co-organizer of the Sztum District People’s Council. Elected chairman of the District Election Committee for the Sejm, he constantly contacted Poznań. Together with his Uncle August Donimirski of Zajezierze, he organized pre-election rallies in Sztum and nearby towns. Count Stanisław Sierakowski did so in villages in the Waplewo area. My father’s cousin Kazimierz Donimirski did the same, in the vicinity of Ramzy and Prabuty. As a result, in the deliberations of the Sejm in Poznań, which took place for three days starting December 3rd in 1918, the delegation of former Royal Prussia (Prusy Królewskie) included seven delegates from the district of Sztum. Other delegates represented the province of Poznań, the former Prusy Książęce (Ducal Prussia), Sląsk (Silesia), and the “foreign countries”, i.e. Poles from Berlin, Westphalia, and other German provinces and cities.

Meanwhile, the Sztum District People’s Council undertook numerous activities, especially cultural and educational, financed mainly by the landed gentry who belonged to it. It organized Polish schools and Polish language courses for adults. Polish kindergartens, so-called “ochronki”, were established.

A plan for armed action was developed in consultation with an underground military organization existing in Pomerania and Wielkopolska. Preparations for an uprising began. The Supreme People’s Council appointed district commissars. The hope was that Gen. Haller’s army, which was to arrive in Gdańsk from France, would support the uprising and help liberate Gdańsk, Pomerania, Warmia, and Powiśle. However, when this army was diverted immediately upon its arrival to the eastern front, the uprising plan collapsed. The People’s Council refocused on preparing for the plebiscite, a referendum vote on whether the area should be under German or Polish rule.

German censuses estimated that East Prussia had a Polish population of about half a million, concentrated in three regions: Warmia, Mazury (Mazuria), and Powiśle. These were the regions that The Treaty of Versailles (1919) decided to include in the plebiscite.

The announcement of the plebiscite, set for July 11, 1920, shifted all previous local activity to a new track. The plebiscite was a great event, experience, and caesura in the region’s history. In my childhood, I often heard this word. Before I understood its meaning, it seemed to be a magic word, a mysterious symbol. For many years, my memories of this period were vivid, with vibrant stories about the people and events during just a few months of preparation. The hope of being reunited with the country suddenly awoke a desire for freedom and the right to express one’s feelings openly, with joy and enthusiasm.

Father traveled to rallies and meetings. Mother, although pregnant, took part in organizing various social events. Packets of colorful paper napkins with Polish inscriptions remained at home from these times. I remembered one of the designs: colorful cockerels along the edges, roosters on the corners, and poetic inscriptions all around: “One rooster is crowing loudly that better things will come, while another rooster sounds a despairing note in its crowing”. The napkins were attached to the propaganda that mother and the other ladies distributed during pre-plebiscite meetings.

At the time, father became the representative of the Polish population of the district to the landrat (starostwo) of Sztum. I remember a business card with his name and surname and the inscription: “Adjoint polonais au Landrat de Sztum“, found by my older brother among some old papers. Unfortunately, after my parents were deported in 1939, the Germans destroyed all our documents, letters, books, and memorabilia.

During the preparations for the plebiscite, my uncle colonel August Donimirski of Zajezierze won a lot of popular sympathy. Earlier, some of the family had taken his serving in the German army badly. After graduating from a military college, he became an officer. He maintained social relations with his colleagues and the German aristocracy. There were rumors of a great romantic love between him and a German princess. However, he chose not to marry for patriotic reasons. He realized that raising the children of such a union as Poles would be difficult. His feelings for her, however, proved lasting. My uncle remained faithful to her until his death, remaining an old bachelor.

In the beginning of 1919, he joined the nascent Polish Army in Wielkopolska. His military experience helped him form the 18th Lancer Regiment in Grudziądz. In May 1920, he was sent back to his hometown for the plebiscite campaign. He organized a Polish Plebiscite Guard in Powiśle and took command of it. After the plebiscite, as a colonel in the Polish Army, he took part in the work of the Border Commission.

Other family members also served in various public positions during this period. For example, Kazimierz Donimirski of Małe Ramzy was, for some time, a member of the Warmia Plebiscite Committee based in Kwidzyn. The Sztum branch of this Committee was located in the home of Franciszek Belau, who paid for it with his life in 1939, even though he was already living in Poland at the time.

Enthusiasts from various parts of Poland visited us on the news of the plebiscite. Some came on their own initiative, others were led by Polish organizations or authorities. Czernin hosted many such people. The most famous - Stefan Żeromski and Jan Kasprowicz - were hosted in Zajezierze by my Uncle August Donimirski during his visit to Sztum. My uncle’s small but very well-kept mansion was located on a lake that separated it from Sztum. Stefan Żeromski, Jan Kasprowicz, and Władysław Kozicki (a writer, art historian and literary critic, later - like Kasprowicz - a professor at the University of Lviv) toured the plebiscite area in May 1920, attending meetings and speaking at rallies. Polish activists and representatives of the Allied Commission received them.

In addition to August Donimirski, they also visited Jan Donimirski in Buchwald, and the Sierakowski estate in Waplewo. They stayed longer with the Kowalski family in Górka near Kwidzyn, as evidenced by entries in the guest book kept there, which was made available to my brother Stanisław, by the daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Kowalski. Many warm memories remain of this stay of famous guests, mainly of Kasprowicz. Żeromski was said to have been somewhat reticent. For this, he touchingly described his impressions in a reportage about his visit of Iława-Kwidzyn-Malbork in the pages of Rzeczpospolita [The Republic, a national newspaper]. He also drafted a joint manifesto of the three participants of this trip, calling for the defense of Polishness in East Prussia. It was handed to the Speaker of the Sejm and announced in the press.

The Plebiscite Theater of Warmia, led by Tomasz Działosz, also arrived from Poland. In Biskupiec, a German militia attacked the group and beat its members, preventing the performance. There were many such assaults.

In the memory of the residents of Sztum and the surrounding area, the most memorable was the manifestation on the Third of May national holiday, which celebrates the original signing of the Constitution. A large parade passed through the streets of the town. On horseback and in historical costumes, The Plebiscite Guard, headed by Uncle August, formed a colorful band. The crowd carried Polish flags and sang “Hello May Daybreak” and other patriotic songs.

A few days later, on May 9, the Feliks Nowowiejski concert in Sztum turned out to be an important event. It occurred in the hall of the so-called shooting range. The program of the concert included works by Nowowiejski: The oratorio Quo Vadis, the Kaszubian Anthem (to words by Derdowski), the Anthem to the Baltic Sea, and the Rota to words by Maria Konopnicka. (The Rota was sung for the first time in Cracow during the celebration of the 500th anniversary of the Battle of Grunwald.) The choir of the Sztum Singing Circle also took part in the concert.

At the end of May, a convention of agricultural circles was held in Sztum under the patronage of my maternal grandfather, Jan Donimirski of Buchwald. Again, the townspeople admired a horse-drawn procession of young people under a banner with the national colors and a flag of agricultural casters. Behind them trailed a long string of vehicles. Their appearance testified to the wealth of organized Polish farmers.

The crowded participation in these events worried and activated the German authorities. Since everyone born in the plebiscite area had the right to vote, even when they no longer lived there, trains with real and fake emigrants arrived from the depths of Germany, mainly from Westphalia. Many East Prussian residents came there, seeking work in factories and mines. It later turned out that thousands of unauthorized participated in the vote, but the Polish side could not control this. This was to be done by members of the Inter-Alliance Commission, composed of representatives of France, England, Italy, and Japan. Only the French were involved in defending the Poles from German militias, and only where there were French outposts. Kwidzyn was the headquarters of the Italians, whose chief, General Angelo Pavia, had no grasp of the situation and acted passively in the face of unlawful actions and terror on the part of the Germans. An Englishman who clearly supported the Germans was in office in Olsztyn. Anyway, nothing was surprising in this; representatives of the German authorities acted as hosts, together with the local aristocracy organized lavish parties in honor of foreign delegations. They were an opportunity for biased exposure of the region’s problems.

In the 1970s, I met Prince Alexander zu Dohna in Olsztyn, whose family owned estates in East Prussia until 1945, mainly in the Mohrungen (now Morąg) district. As a 20-year-old, he was secretary to some dignitaries involved in the plebiscite campaign. In the prince’s opinion, the plebiscite was conducted fairly. He was a man of integrity, high culture, convinced of his impartiality. Like him, many Germans, influenced by prepared information, did not realize the true state of affairs. They were later surprised by the facts and data revealed by Polish historians after the war on the basis of German documents.

In line with expectations, the German side was perfectly organized. It used the entire old administrative apparatus. According to international agreements, both the police and the army were to leave the plebiscite areas. Theoretically, this was done. However, the German authorities organized the civic guard set up for security. Its ranks included the most fanatical nationalists and many existing police officers. This guard not only tolerated the terror of nationalist militias, it even favored them. The spontaneously organized few Polish plebiscite guard units could not oppose them.

The German government allocated large sums of money to the propaganda campaign. The population was inundated with appeals and information speaking in favor of the German side. The regional patriotism of Mazurians and Warmians was very skillfully aroused. Some sort of autonomy for East Prussia was suggested vaguely. In the end, voters had a choice of two cards: Polska (Poland) - Polen and Ostpreussen - Prusy Wschodnie (East Prussia)–not “Germany”!.

However, the greatest threat to the results of the plebiscite was the Polish-Soviet war, which was currently underway. Due to the proximity of the front, German propaganda proclaimed that Poland would once again disappear from the map of Europe, and whoever voted for Poland would choose the Soviet Union. Indeed, the Polish state was in mortal danger. The Polish government was unable to assist in the plebiscite campaign. The entire burden fell on the shoulders of local activists, supported by volunteers from Poland.

Sztum County was among the most Polish in the plebiscite area. Thus, in many of its municipalities, the majority voted in favor of Poland. In the administrative district of Czernin, all but one vote was cast in favor of Poland. It was suspected that this was the vote of a teacher from the local school, a cultural enforcer specifically installed by the authorities to promote German assimilation. Unfortunately, districts with a preponderance of German votes often separated Polish municipalities from the Land. Therefore, in the end, only a few Vistula River municipalities ended up in Poland.

Poles questioned the results of the plebiscite. Many people did not dare to vote according to their convictions. They were intimidated by the German authorities and the terror-sowing militias. It was said in our country, that the Polish Sejm passed a resolution demanding the invalidation of the plebiscite results. However, Poland’s position in the international arena was too weak for its voice to be heard.

Residents of the areas incorporated into Germany after the plebiscite could “opt” for Poland, that is, demand transfer to Poland. In an atmosphere of general despondency, many of the more informed Poles declared such an intention, often out of fear of reprisals. After a while, some wanted to withdraw their application, but the German authorities consistently enforced their departure.

Of my family, Uncle August had to remain in Poland because he was accused of desertion and treason as a former German army officer. Zajezierze was still his property, but he could not return there. However, he did not sell the estate, as this would have resulted in transferring the land into German hands. This was because a law granted the right of first refusal to the Colonization Commission, whose task was to strengthen the German element in East Prussia. It was not until 1938 that my uncle carried out an exchange of Zajezierze for the estate of Nowe (near the Pomeranian town of Nowe-on-Vistula, on the German border), which a German owned. The Polish authorities supported and facilitated this transaction; in this case, they were keen to weaken German land ownership within Poland’s border. My uncle was happy, thinking that he had finally found a peaceful haven for his old age there.

Soon, however, the war drove him out to wander under the constant threat of arrest by the occupation authorities. In 1939, almost all Polish plebiscite activists were captured by the Gestapo, regardless of whether they continued to live in East Prussia or moved to Poland. The Gestapo had detailed lists of Poles connected with the plebiscite campaign and their addresses. Most were murdered in concentration camps, as my father was, or shortly after being arrested. As I learned from Andrzej Bukowski’s book Waplewo, Stanisław Sierakowski was bestially tortured in an “execution house” in Rypin, where his wife was also shot, and his pregnant daughter was killed with a shot to the back of the head. Uncle August, fortunately, was not found by the occupiers, and thus was among the few who escaped vengeance.

People involved in the Polish cause during the plebiscite deserved a worthy place in the national memory. The better-known names figure in the works of historians. A great effort was made by Professor Tadeusz Oracki, who recorded in Słownik Biograficzny Warmii, Mazur i Powiśla [the Biographical Dictionary of Warmia, Mazury, and Powiśle] the characters of many dedicated, uncelebrated, humble people, based on the few remaining documents, materials and memories.

From an early age, my parents grew up in an atmosphere of faith in the rebirth of an independent Poland, within whose borders both Pomerania and Powiśle would be included. Thus, it was very difficult for them to come to terms with the loss. They began to think about moving to Poland. At that time, many Germans, owners of estates in the areas returning to Poland, mainly in the Poznań province, were willing to swap for estates in Germany. Fearing that they would find themselves in a position similar to the earlier situation of the Poles, they were willing to give up double the acreage of land they had received. Thus, there was the possibility of even a favorable transaction. On the other hand, however, it was not easy to leave the family home and simultaneously abandon the outpost of the struggle for Polishness that had been waged here for generations.

An exodus of more conscious Poles from our region was looming. There was a danger that only less educated and less well-off people, susceptible to rapid Germanization, would remain. The Polish authorities did not want to allow this to happen. They believed the landowners should remain to provide moral and material support for the local population. “You are at the post, persevere!” - the Ministry of Foreign Affairs representatives repeated. So, my parents agreed to stay and continue their activities from the time of partition. It seemed that in the changed conditions, thanks to the existence of the Polish state, it would be easier and more effective.

As it turned out, the German authorities pursued a similar policy concerning the territories that fell to Poland. They urged Germans to stay, hoping to reoccupy these lands. Throughout the twentieth century, a stream of financial aid flowed from the Reich to German schools and organizations. Agents were arriving and instructions were coming. There were few opportunities for the Polish side to act in Germany, which turned totalitarian in the 1930s. The Poles who engaged in these activities paid a high price. Meanwhile, nationality criteria did not play a significant role in establishing borders after World War II. However, no one could have foreseen this.

After deciding to stay put, my parents wanted to secure some point of support in Poland. Therefore, they bought the Marusza estate in the Grudziądz district, i.e., on the Polish side of the border. This did not affect the status of my family. We were citizens of the German Reich, with permanent residence in Czernin. If we wanted to go to Poland, we had to have a German passport and a Polish visa. Fortunately, the regulations did not pose major obstacles to obtaining a passport. It was generally issued for five years. It was not until the Nazi authorities began to restrict the right to a passport or even deny it. The Polish visa was, of course, issued to us without difficulty by the consulate in Kwidzyń.

For centuries, the Malbork region has been closely connected with Gdańsk Pomerania. At one time, together with Warmia and Pomerania, it constituted Royal Prussia. During the partitions, it was the Prussian province of West Prussia (Westpreussen). This was in contrast to the former Ducal Prussia - the province of East Prussia (Ostpreussen), to which Warmia was incorporated. The border established after the plebiscite often divided families and split organizations operating on either sides of it.

Initially, despondency prevailed. However, it did not last long. Just four months after the plebiscite, the leaders of the Polish community of Powiśle and Warmia, along with one representative of Mazury, met in Olsztyn and formed the Union of Poles in East Prussia, to which Powiśle was annexed after the plebiscite. A year later, the Polish Catholic School Society of Warmia was established in Olsztyn, followed by the Polish Catholic School Society of Powiśle in Sztum shortly after. Economic, cultural, and youth organizations were revived. The Olsztyn-based Gazeta Olsztyńska [Olsztyn Gazette], which had been published since the end of the 19th century, continued to come out in Olsztyn.

My family’s local initiatives and experiences contributed significantly to the forming of the Union of Poles in Germany in 1922.

It covered the Polish population in the entire German Reich, divided into five districts:

- Śląsk (Silesia)

- Berlin

- Westfalia and Nadrenia (Westphalia and the Rhineland)

- Prusy Wschodnie (East Prussia)

- Pogranicze (Borderlands) consisting of Ziemia Złotowska, Babimojszczyzna and a slice of Kaszuby.

From then on, the union took on a leadership role, developed political messaging, and represented Poles officially before the German authorities. The individual organizations generally developed independently, depending on local conditions and the personalities of the organizers, but united under the Union of Poles to increase their strength and capacity for action.

Organic work: “The slogan of the Polish positivists after the January Uprising, calling for the defense of the national survival not through armed struggle, but through the development of the economy and education”. <source: https://sjp.pwn.pl/sjp/praca-organiczna-praca-u-podstaw;2507734.html>. Read https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Organic_work for more information.↩︎

Our Family Nest - Czernin

(1920-1930)

When my Great-Great-Grandfather Antoni Donimirski purchased Czernin in the first half of the 19th century, the estate bore the official name: Hohendorf. As customary then, the family generally used the Polonized version: Hondorf. In old documents, my father once came across the name: Cerninen. It is not known whether it was derived from a Polish name that existed years ago, which presumably sounded “Czernin,” or whether the Polish name was created by interpreting an Old Prussian name. Regardless of these inquiries, we liked “Czernin” better than “Hohendorf” and began to call our hometown by this name, of course, only in our circle. This custom proved especially useful when, during the war, in view of the threat of the Gestapo, we could use this name in letters and conversations to avoid betraying our place of origin. After the war, we were pleased to hear that this name was officially approved.

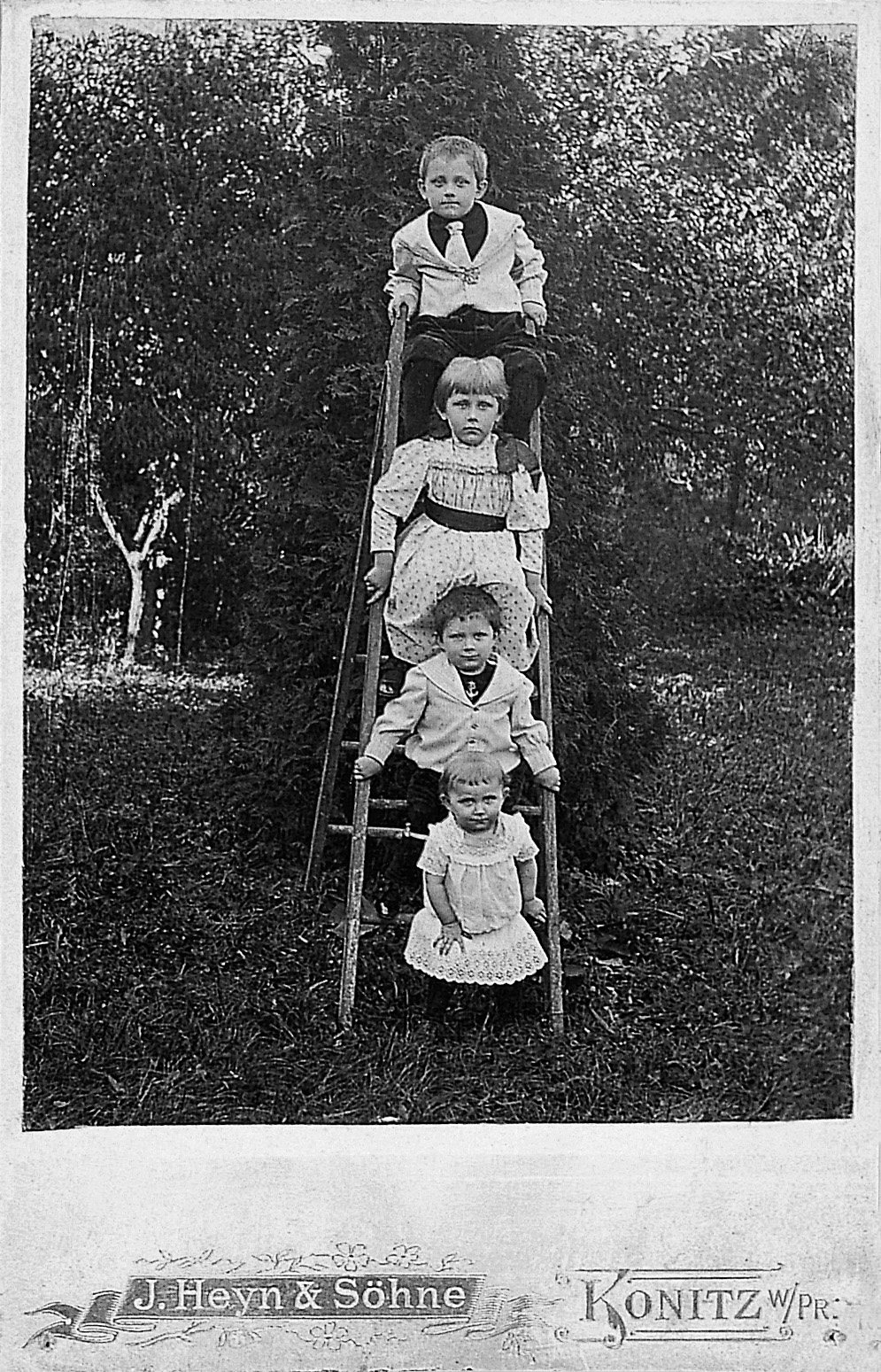

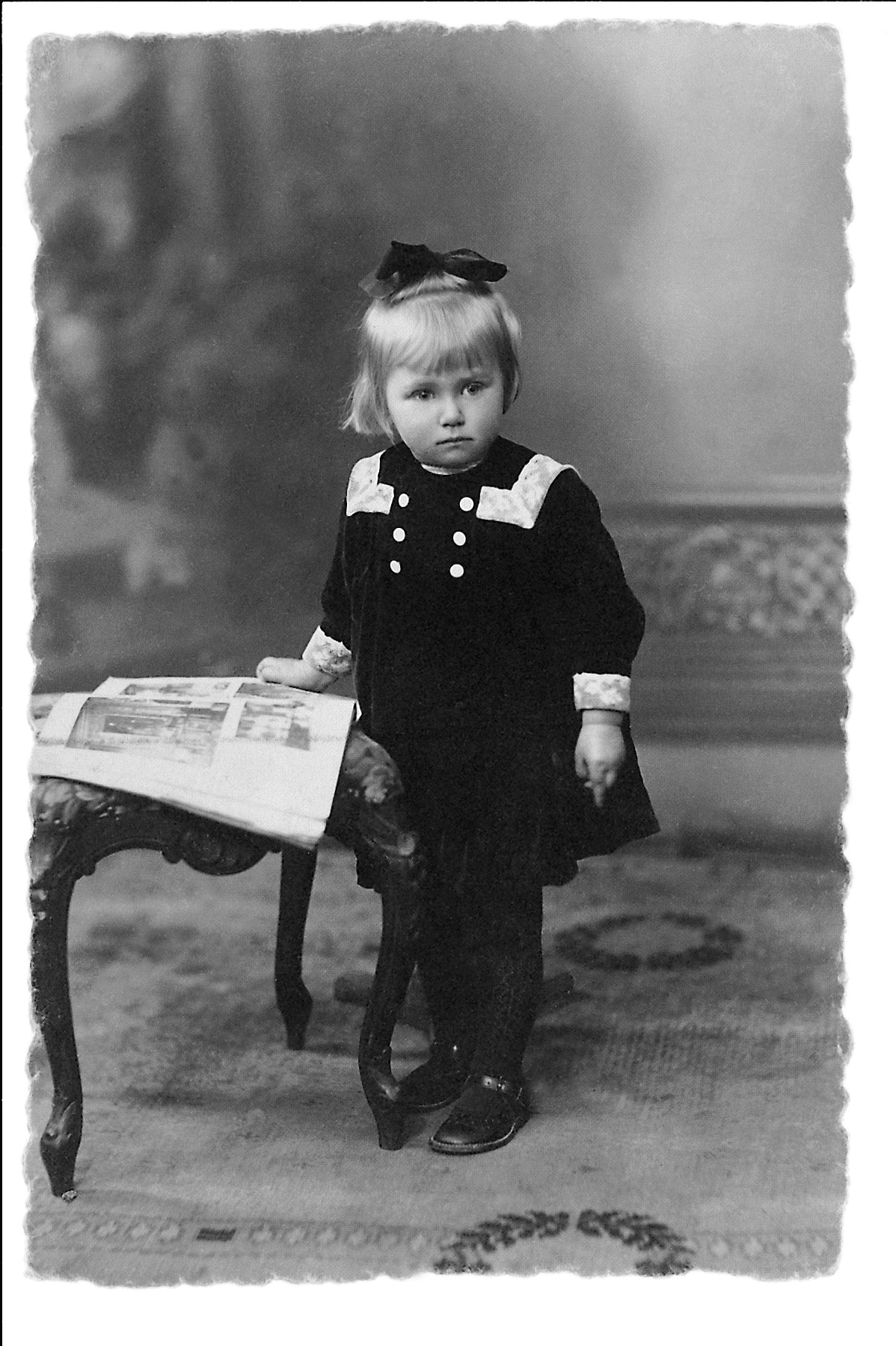

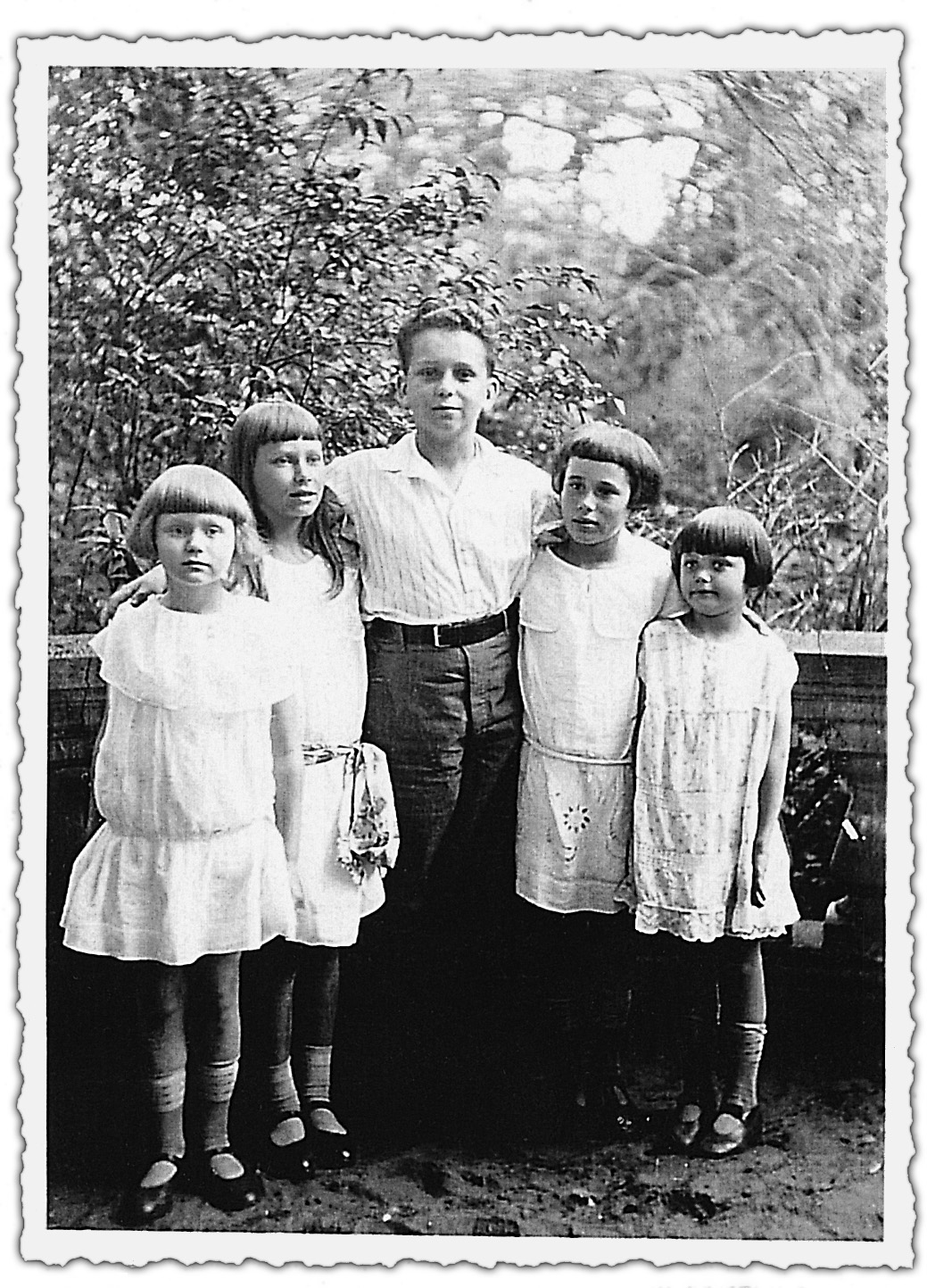

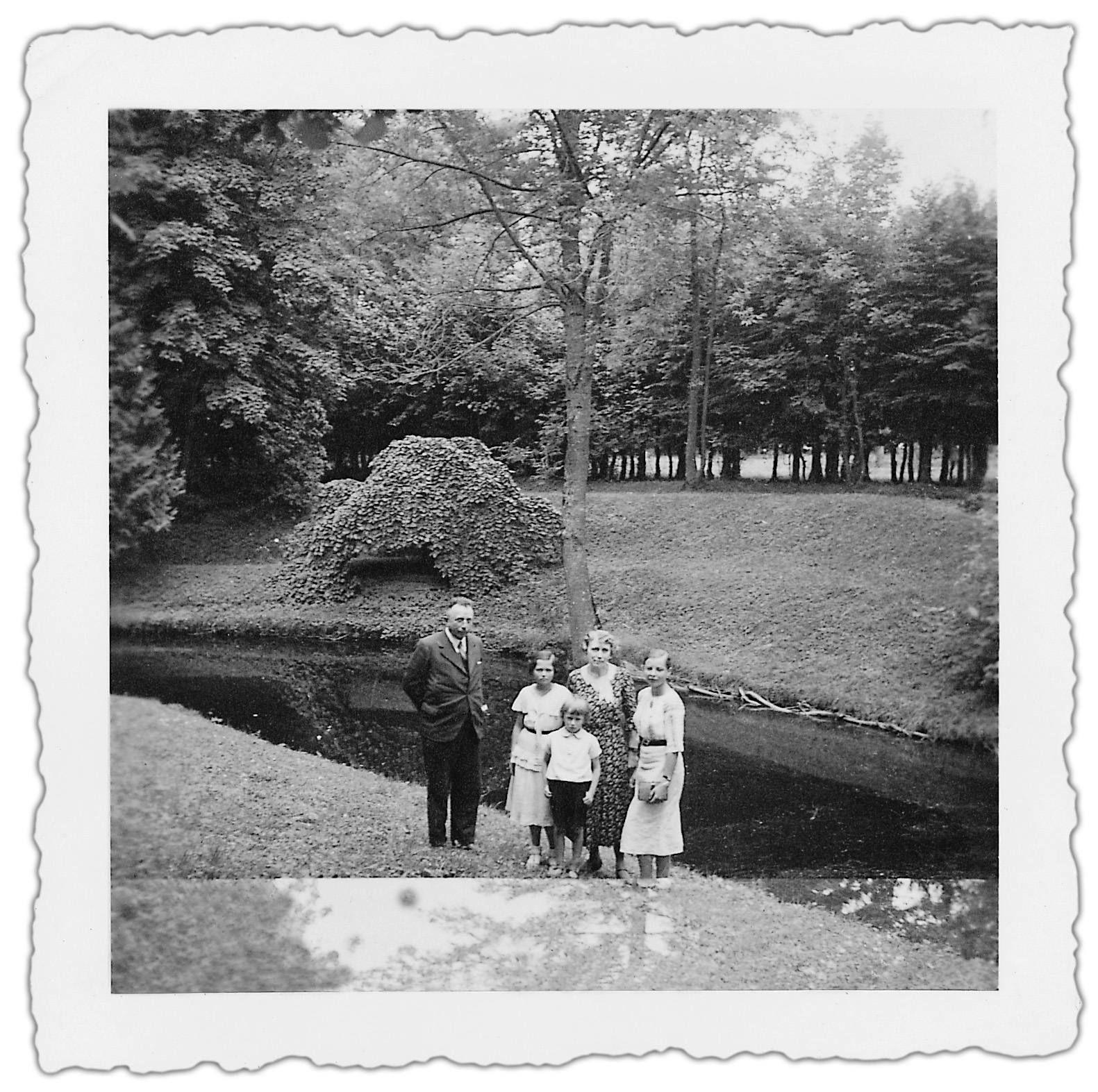

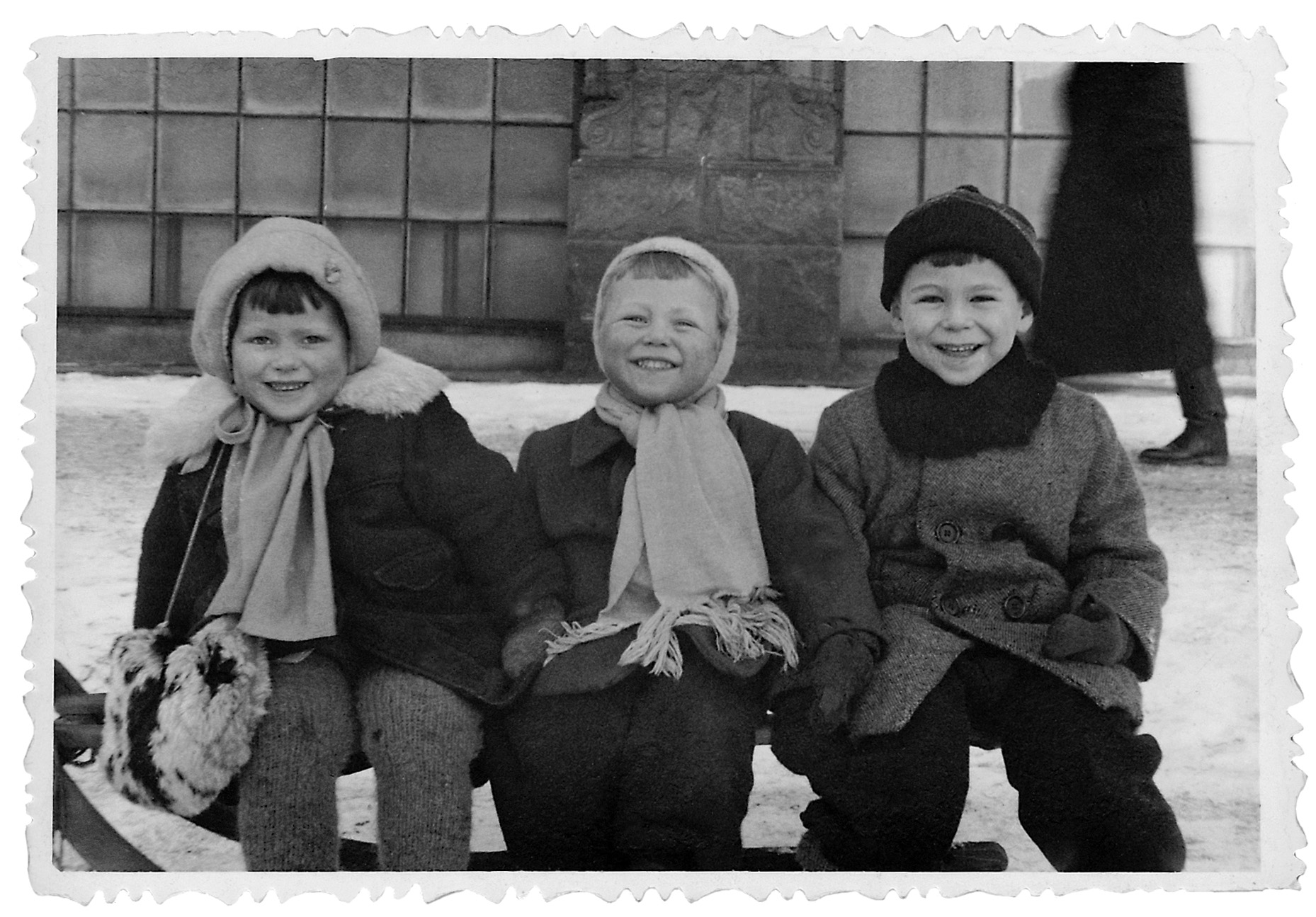

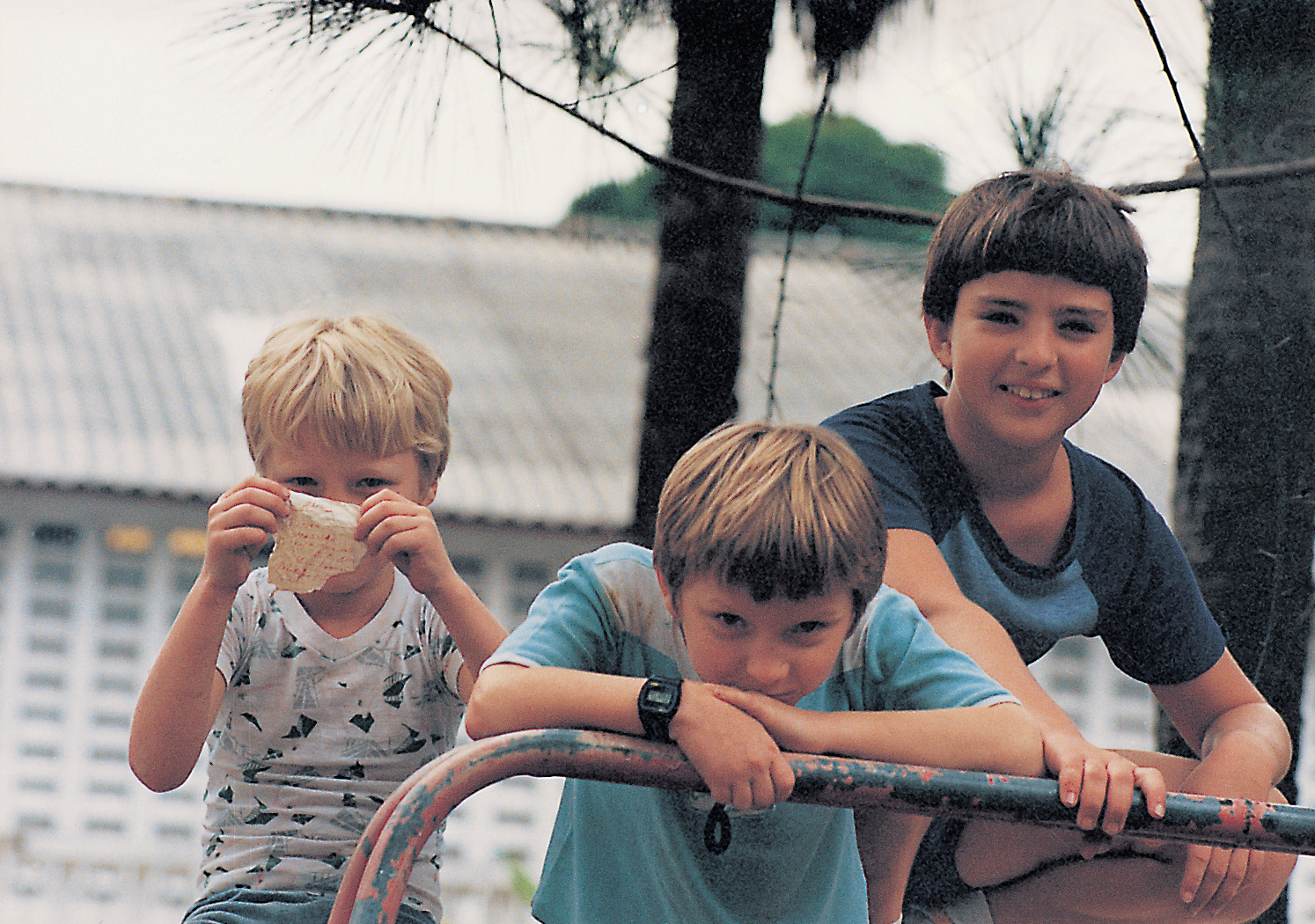

My parents had eight children. The eldest son was born in 1911 and was named Zygmunt in honor of his grandfather. However, he died when he was six months old. A year later, another son Olgierd was born, and in 1915, Czeslaw was born. My parents also lost him when he was less than three years old (the doctor failed to diagnose appendicitis). My birthday on January 18, 1918 gave birth to a series of girls. The names Halina Antonina were chosen for me. The second name was supposed to provide me with a peaceful patron saint. In 1919, Bogumiła was born, so named in honor of a long-lived great-grandmother. In 1920 Irena was born, and in 1922 Ewa was born. The youngest brother, Stanisław, taking this name after the second grandfather, appeared after a gap of several years, in l928.

Olgierd, who was five years older than me, grew up separately, while my sisters and I were inseparable. As small children, we diminished our names in various ways, and eventually, these diminutives took hold among adults as well. My older brother we called “Olo”, I was “Tina”, Bogumila - “Lili”, Irena - “Renia”.

I was supposedly a calm and obedient child, the opposite of Lili, a year younger than me, who caused a lot of trouble. It was joked that in order to get her to do something, you had to instruct her not to do it. When she reached the age when children begin to speak, attempts were made to teach her words: “mom”, “dad”, and “baba”. She, however, remained stubbornly silent. One day she unexpectedly called out: “mama-tata-baba-ciu!”, and seeing that the exclamation was impressive, she began to use it daily as a universal slogan for expressing any feelings, wishes, or protests. Of course, this didn’t last long, and soon she began to express herself in normal childish language. There were still a lot of problems with her for a long time, which caused some concern for her future. However, it turned out that after going through a period of youthful “storm and stress”, when she married and had children herself, she became a model of diligence, kindness, and benevolence without losing any of her fiery temperament.

Our father was brown-haired, our mother a blonde. Our bunch inherited these traits in turns. My older brother was a brunette with hazel-colored eyes and beautiful dark curls. When he grew up, he struggled with those unruly locks, applying a net at night to smooth them down. Many people used to say: What’s the use of such hair to a boy? It would have been better if nature had bestowed it on his sisters! Unfortunately, of the four of us, only Lili had dark wiry hair, harmonizing with her bohemian beauty. Renia and I were blondes with blue eyes, and Ewa, for a change, had dark hair and blue eyes. The youngest Staś, on the other hand, had hazel eyes, even though he was blond. And his hair was also arranged in beautiful waves!

When we were still small, when guests visited we were allowed to go to bed a little later, which we always fought for. We would then sit with everyone at the table, and Renia would open her big blue eyes wide to stay awake. She had a round face and, according to the unanimous opinion of the whole family at the time, resembled a young owl. Soon some dear aunts supplemented these bird comparisons, calling Lila a “swallow” and me a “lark.”

Ewa was probably not even two years old then and had not yet participated in our games. However, she watched them with interest. It often happened that she would stare for a moment at some toy in our hands and then suddenly throw herself at it, snatching it up by surprise. Then she would quickly shelter under the protective wings of adults, who invariably told us: “Let her play. She is so tiny after all!”. We felt wronged and ruled that Ewa should be called a “hawk”.

From an early age, we loved our home very much. It was always warm, cozy, and caring to us. We believed that its appearance gave us a sense of security, and we identified it with beauty. In front of the house, an oval lawn stretched with flower beds, separated by a low wall. The wall was overgrown with ivy, and was decorated with stone cannonballs placed at certain intervals, the kind that can be seen at Malbork Castle. Two large balls also rested on pillars on either side of the porch.

A coat-of-arms leaping deer with three stars adorned both gables of the mansion, topped by a distinctive broken roof. It was covered with a dark tile, shining with a greenish-brown glaze. Father would bring in these tiles on special individual orders for repairs. The roof was essential to the house, contributing to its historic, stately appearance. When, in the late 1970s, a major renovation was carried out (for which great credit should be given to both the decision-makers and the contractors) of the building, which had been badly damaged during the post-war years, the roof was covered with ordinary red tiles. The house’s appearance lost a great deal in this, taking on a more common character.

On the other side of the detour, around the lawn, stood a row of tall spruce trees, which, along with a string of shrubs, obscured the courtyard behind them. My childish imagination attached various notions to them. I saw them as mighty bearded warriors standing guard over the house. As the whirlwind battered their branches and bent their tops, it seemed to me that they were fighting a desperate battle against some evil force. In winter, covered with snow, they reminded me of stately old men with gray beards.

From the porch, one entered through double doors into a large hall furnished with black oak Gdańsk furniture. Beneath a large chandelier, which was a weave of deer antlers, stood a polygonal carved table resting on four legs shaped like massive Baroque columns. On the table lay albums devoted to art. Unfortunately, some of the reproductions bore the not-so-glorious traces of our painting interests from our early years. Large leather-covered armchairs with carved backs surrounded the table. The backrests were topped with five-pronged crowns supported on the sides by lions and a shield with the coat of arms of Gdańsk in the center. Against the wall stood an old-fashioned clock with a pendulum and weights, showing not only the hours but also the days of the week, month, and dates and phases of the moon. A coat rack with a mirror in the middle was at the main entrance. Across from the entrance, a glass-enclosed library cabinet drew attention on the right, and a richly carved chest on the left, both in the same style. In the hallway, Father received visitors - strangers who were not invited into private rooms.

To the right of the entrance, a wide, dark brown wooden staircase with a massive handrail supported by fancy carvings led to the first floor. Beneath this staircase was a small storage room at my father’s disposal, locked with a padlock. A low door next to the door to his study led there. According to a conservator from Gdańsk, this staircase contains characteristic elements of rustic baroque and is older than the entire building. They were probably moved from the manor house that stood here earlier.

Opposite the front door was the door to the living room. It was a large room with access to the veranda, lit by four windows, two on each side, punctuated by narrow, tall mirrors in gold frames resting on gilded consoles. The room was divided as if into two parts. Each contained a table, with a sofa beside it, armchairs, and padded chairs - in the Art Nouveau style typical of the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. I believe they were purchased on the occasion of my parents’ wedding. A black grand piano stood against one of the narrower walls of the room, and in the corner against the opposite wall was a disused fireplace flanked by an undersized screen, the wings of which bore my parents’ coats of arms: the stag in a leap, which was the Donimirski’s coat of arms - Brochwicz, and the wood grouse, which was the coat of arms of my mother’s family.

The living room was part of an amphilade. Adjacent to it, on one side, was the dining room; on the other - the so-called lounge, and further on - the “boudoir”. The latter was filled with white, stylish furniture protected by covers and a large mirror in gold, with richly carved frames. It was not shared but was used by my mother to store things that were temporarily unnecessary but which she wanted to have on hand. In the boudoir, the radiators were turned off and the windows were covered. It was therefore cool, so my mother often stored candy and fruit there, especially during the holidays. On the other hand, the adjacent lounge was where family life was concentrated. This is where the radio was located and where we met to chat.

Adjacent to the living room on the other side was a spacious dining room, whose furnishings were in style with the furniture in the hall: a large chandelier composed of carved pieces, a large table, extending as needed. Around the table and along the walls were 24 leather-covered chairs with carved backs like those in the hall. The carving patterns were also the same, the same coat of arms of Gdańsk with lions, topped with a crown. The backrests were very heavy. When, as children, we sometimes jumped violently from our seats, it happened that the chair would topple over, and one of the five spherical crown sticks would fall off. They were glued on with carpenter’s glue. In addition to this damage, you could also see the claw marks of our beloved cats on the leather seats.

We owned some cats that consistently did all sorts of damage to the house, primarily by sharpening their claws on the upholstery of the Gdańsk furniture. Our parents were angry about this, but our housekeeper would come to our rescue. In time, this destruction began to worry us, too. When we grew up a little, we were already trying to protect this beautiful furniture ourselves. In addition, in the dining room stood a large Gdańsk cabinet and similarly carved two black sideboards, which we called buffets. One of them was very large. Both held china, glassware, and crystal, while the cupboard held tablecloths, napkins, and other table linen.

Behind the dining room was a room called the kredens, a walk-in cupboard room, which led to the kitchen. In the cupboard room, meals were prepared and dishes were washed. The laundry was done here. In addition to the door to the living room and the sideboard, a door led from the dining room to a small corridor connecting the hall and the kitchen corridor. A similar hallway was located on the opposite side of the hall. A swinging door glazed with colorful stained glass led to both from the hall. This second hallway connected my parents’ sleeping quarters with a bathroom, a boudoir, and a sitting room. A narrow, steep staircase led upstairs to the children’s rooms.

In my earliest memories, those stairs weren’t there yet, and upstairs there was a huge hallway leading to only five rooms. The girls on duty with us occupied the largest room, by the kitchen staircase. The other rooms were for guests. In the 1920s, during our stay in Marusza, my father did extensive renovation and remodeling of the house. On the first floor, several rooms with mansard windows built into the mansard roof were created above the parents’ bedrooms, living room, and boudoir. These were designated for our bunch, with two of them initially occupied by our teachers. Later, four of us got our own separate rooms, with only the two younger sisters sharing a large room - previously the sleeping quarters of all four of us. Its window looked out to the west.

We could see the overseer’s house through the bushes and branches of the trees, and further on the gardener’s house. We liked watching the sunset through the open window, especially on summer evenings. Years later, when we returned from school on vacation, we were bursting with overwhelming joy that here we were again in our beloved home. We would then soak up this familiar view and often sing. We were especially fond of a song by Moniuszko, which we felt reflected our mood well:

On a quiet evening, a May night, a song vibrated in the distance after the dew. The heart hears every word, Every note it knows well! Always to us anew Soothes our soul this silence….

In the depths of the garden in Czernin, there was a round family chapel. My great-grandmother built this chapel as a tomb for her beloved son Wacław. She plunged into despair after his tragic death. He died as a young boy in front of her eyes as he was riding a horse that threw him to the ground and hit him on the head with a hoof. Next to the chapel, rose a mound with a square stone on top, probably representing the top of a stone prism that had sunk deep into the ground. The corpse of the horse that became the cause of young Wacław’ death was reportedly buried under this mound. An inscription was said to have been placed on the stone, informing of the entire event. Such a message remained in my memory from my childhood years.

My great-grandfather and two prematurely deceased brothers were later buried in the crypt of this chapel, in which family religious ceremonies were held - our baptisms and first communions. In addition, from time to time, my parents would invite the local priest to say Mass, for the intention of the deceased and living family members. All the household members attended the services. Miss Ola Morawska came from Sztum. The families of our employees, more closely related to us, also participated. It could have been assumed that our weddings would also occur there, but the war and related events drove us out of our family nest.

The chapel survived the war, but as early as 1945, it fell victim to vandals who wrecked it and desecrated the coffins. Visiting Czernin from time to time after the war, we watched with pain as it gradually turned into a ruin. Unfortunately, we no longer had any rights to our family seat.

Our life in Czernin went on according to traditions established years earlier. At eight o’clock, the maid would put breakfast in the dining room. The family did not eat this meal together, but everyone came individually. Arriving at the dining room in the morning, we found our father, who usually showed up first. We kissed his hand for a “good morning”, and while eating, we talked about various current affairs. We met with my father mostly at the table. He left our health care and studies to our mother, although he was very interested in our performance in every field.

Before noon, father mostly took care of the farm. He did not rely on the administrative staff, as some of our neighbors confirmed. He would ride a light carriage into the field to assess the condition of the crops or to see to the crops or harvest the crops. He often went out into the yard and talked with the people working there. He was not one of the approachable people. Everyone respected him, but they knew he was fair and would not harm anyone.

Around half past one, the gong called for lunch. The whole family would meet then, including the groundskeeper, who always sat next to my father and discussed farm matters with him during the meal. We had to behave quietly and politely. However, sometimes, one of us would start grimacing or arguing with a neighbor. My father would interrupt the conversation and say briefly, “Lili, out the door!” I just mentioned this name because this sister of mine was most often met with such a punishment. But I also remember myself, deeply embittered, sitting on the threshold behind the closed door to the dining room. Sometimes Lili did not respond to her father’s command, and then my brother had to enforce it. Years later, he admitted to me that this made him very uncomfortable. After a while, my father would say to my brother: “Bring her back”. Olo opened the door, and a small person appeared, drenched in tears, with a long napkin tied around her neck. After a whispering “Excuse me”, she would return to her seat. However, the mood quickly improved.

At some point, our parents would let us get up from the table, and the adults would drink a cup of black coffee each. Meanwhile, we would line up in front of the door of our father’s office, and when he came, we would flag him down, shouting: “Ciu-ciu! ciu-ciu!”. Father laughed, playfully covered his ears, opened his stash in the hall under the stairs, and poured a few candies for everyone. We would kiss Father, thank him, and then siphon off the candy we received, and a fair distribution of quantity and quality would follow. Usually, the dividing was my responsibility. Mother often protested with laughter, saying that candy was not healthy, but this tradition survived for many years.

There were also fun games with my father. Sometimes he would play “hide and seek” with us, finding us in various hiding places; then again, he would chase us around the rooms. We, of course, were happy, and our father also laughed like never before. Generally serious, he smiled often, but laughed rarely. We loved father dearly, although he was strict and demanding. He attached great importance to punctuality. When we left for church on Sunday, he required us to be ready at the appointed hour and get into the carriage with our parents. Those who did not show up had to walk to the next service, joining someone from the service. However, I don’t recall my father hitting any of us. A stern rebuke was sufficient. On the other hand, Mother, who stayed with us a lot more, sometimes knocked us out by the hands. I remember being so punished when I stuck my younger sister’s fingers through the door while playing.

For most of the day, my father worked in his office. Entry to this room was basically forbidden to children. From time to time, however, we were allowed to stay there, which gave us great pleasure, and we were then happy to use the “rocking” chair located there. We ran to our father to kiss him goodnight in the evening, already in our nightgowns. We always found him at his desk, illuminated by a standing lamp with a green shade, bent over papers.

Father’s study was cluttered with furniture. On one wall stood a large library cabinet filled with books. In addition to a multi-volume German encyclopedia, there were various other encyclopedic publications, dictionaries, and professional handbooks, in Polish and German. Along the other wall stood a leather-covered couch and two armchairs, with a large table in the center and stacks of various papers lying on it. It gave the impression of a terrible mess, but there was some sort of thematic arrangement to it, and father always found what he was looking for quickly. The wall above the couch was decorated with antlers of game hunted by father. Opposite were two windows. In a corner by one of them stood an old-fashioned desk, also perpetually set up with magazines and correspondence. In the cabinet rising above it were a multitude of drawers and shelves, also tightly filled. Under the other window was a woven rocking chair. When father was devising some writing or any matter at all, he would sit in this chair and swing slightly.

Father was immensely interested in new inventions. He followed the appearance of modern agricultural machinery and usually bought it after analyzing its usefulness. I recall him explaining to me the workings of a reaper adapted for mowing outgrown grain. In the past, this had to be done by the reapers, and the girls followed them and tied the sheaves by hand, which was very labor-intensive. The modernized reaper had a device that lifted the lodged grain and its work was much cheaper.

But innovations interested my father not only on the farm. When the radio became widespread in the mid-1920s, he was among the first in the area to acquire the equipment. It was a massive apparatus with five large and several small dials. The dials had to be set to the right combination of digits to enable one to hear a station. The essential camera still needed a large and heavy battery and a separate speaker. For a long time, our favorite activity was discovering new stations. We would write in a special notebook the digits to which each dial had to be set.

Every day, the radio was set to Warsaw. At noon, my father would turn on the apparatus, and the bugle call from the Mariacka Tower in Cracow would sound throughout the house, followed by the news. I was very attached to the bugle call. When I stayed in my Warsaw apartment, I set the radio at noon, and the trumpet’s voice took me back to my childhood.

I can no longer remember in what year my father bought his first car, arousing great enthusiasm in our bunch. It was a Ford convertible, a spacious, multi-passenger vehicle. We liked to drive the car uncovered, but the periods when the weather allowed it in our climate were relatively short. Mostly we had to use a “kennel”.

People who stayed with us said that the house was well organized. Mother received guests warmly, and everyone brought back fond memories. Running such a house involved a lot of money, despite my mother managing frugally and, above all, rationally. The father contributed certain sums to the house and supplied the kitchen with the estate’s own products, i.e., milk, meat, potatoes, or flour. As a passionate farmer, he dreamed of more and more improvements to the farm, and modernization in various areas, and tried to allocate the bulk of his income for this purpose. Mother never questioned this, but in order to have her own resources for the house and children, she organized large-scale poultry farming.

Every year from March to May, she would run electric incubators, obtaining several throws of hens, ducks, and geese. She also raised turkeys and guinea fowl on a smaller scale. The incubators required constant temperature and humidity control. Mother would even get up at night, as fluctuations in temperature could happen, and destroy many embryos. As children, we experienced all the activities involved in hatching chicks. Taking turns, one of us could take part in it. Each egg had to be marked with two longitudinal lines, blue on one side and red on the other. Several times a day, they were turned over once to the blue side and once to the red side. After a while, all the eggs were x-rayed to eliminate the unhatched ones before they spoiled and were destined for feed. We eagerly awaited the day when the chicks would begin to hatch. We were delighted with them and enjoyed participating in their feeding.

In autumn, on the other hand, among the great games was making noodles for the geese. Geese destined for fattening sat locked in one room of the hen house and were fed by slipping oblong noodles into their beaks. I did not witness their feeding, but I remember with what enthusiasm, standing on the kitchen bench, I would roll the oblong rolls from the prepared dough. Everyone bought geese for St. Martin’s Day in our neighborhood, probably all over Germany and the former Prussian partition (November 11). This was also the customary day for moving, a date probably chosen to be in time for the coming winter.

Mother also derived a small income from the garden. This name meant to us park, orchard, and extensive vegetable garden. It was generally in deficit, but the cost of labor, fertilizer, and some purchases charged the estate account. Mother managed the whole thing, having a gardener. He was often assigned larger jobs by the groundskeeper. Mother subscribed to various gardening magazines to run the garden as rationally as possible. Fruits and walnuts were not for sale. Two giant walnut trees grew in the park in front of the house. The image of potato sacks full of nuts, carried to the cellar in autumn, remained in my memory. They were intended for our needs and gift-giving to various people and for Christmas supplies to Polish orphanages and organizations. Also, winter apples were distributed by mother at Christmas. Some durable varieties remained for the house until late spring.

In the vegetable garden, many bushes of raspberries, currants, and gooseberries grew along the flower beds, and every year we had an extensive plantation of strawberries. At that time, the health-giving properties of vegetables and fruits were already being promoted, so mother allowed us to play in them to our heart’s content. She often invited friends to come and pick their own fruit. Others carried full baskets on various occasions. The gardener traveled twice a week to the market in Sztum, where he sold vegetables.

As far as I know, they were popular. In general, they were plump, and in our town, the supply was not among the best. A conversation between my mother and a lady who asked if the gardener received a commission on the vegetables he sold was stuck in my memory. My mother laughed and replied: “In theory, yes, but in practice, he pays me a commission. However, I’m looking at his activity from a bigger picture, because, after all, I’m not going to monitor these small sums”.

So there was no shortage of fruits and vegetables on our home menu. Mother tried to make it conform to the latest currents in the field of dietetics. During the day, mother was too busy to pick up a book or magazine. She devoted her evenings to this, often sitting up late into the night. She subscribed to magazines published by the Union of Poles in Germany, the women’s magazine Bluszcz [Ivy], Przewodnik Katolicki [The Catholic Guide], and others whose titles I don’t remember. In the evenings, she also prepared papers for meetings of women’s organizations. When I sometimes felt sick and woke up at night, I would run to her room and find her with her head bent over reading or writing, in the light of a night lamp standing on the table. The youngest child slept in her room, so she kept it semi-dark.

Mother devoted much of her time to social work, focusing mainly on two Polish women’s organizations - Towarzystwo Ziemianek (the Society of Landed Gentry Women) and Katolickim Towarzystwie Kobiet im. Świętej Kingi (St. Kinga Catholic Women’s Society).

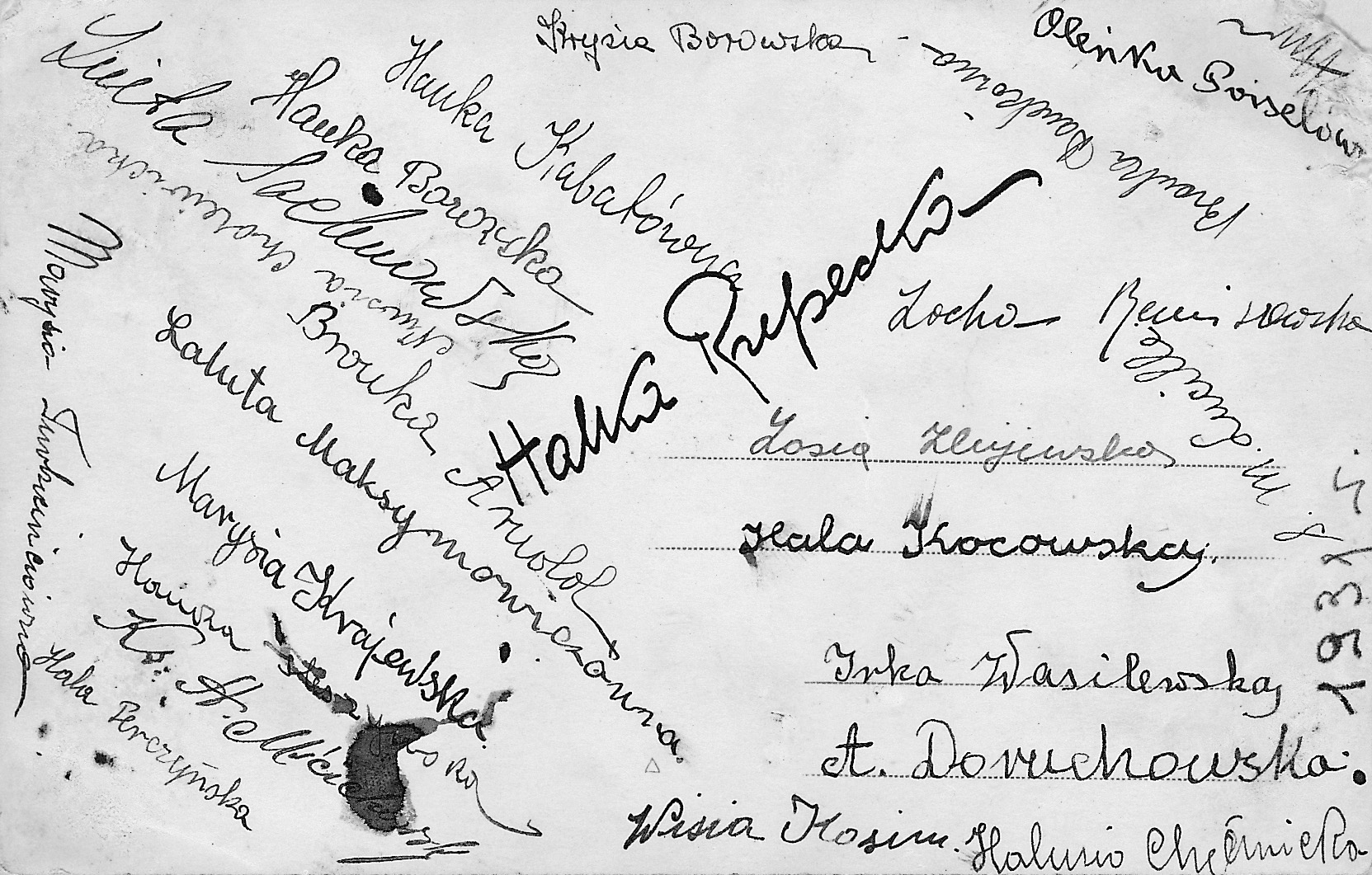

The former was an activist organization. Its name probably remained from earlier times. It included ladies Helena Sierakowska, Emilia Chełkowska, Izydora Osińska, Aleksandra Morawska, Aunt Marysia Donimirska, and the Gawroński sisters from Postolin. These ladies met regularly, very often in Czernin, and arranged work plans. Tasks were distributed, such as taking care of kindergartens, preparing various events, and handling meetings of the St. Kinga Society.

The latter organization included village women, who formed circles in individual villages. Circle meetings were generally held once a month. The first part was a lecture on current, religious, and national topics. It also included practical advice on health, cooking, and farming. Information was provided on local events and happenings. My mother was one of the most popular speakers. After Helena Sierakowska and Emilia Chelkowska left for Poland permanently, the main speakers left were Aunt Marysia Donimirska from Ramzy and my mother. As a child, I began to participate in this activity quite early. My mother used to take me to meetings to spice them up with even a modest “artistic part”. I used to recite childish rhymes by Maria Konopnicka, fairy tales by Ignacy Krasicki, and later more serious but easy-to-read poems with mostly historical, patriotic content. The participants received my performances very warmly, with great applause.

The meetings ended via a shared “coffee”. We always carried the traditional large yeast crumble cakes to the meetings. Coffee was served with them. A social chat followed, usually in an enjoyable, cordial, and cheerful atmosphere. For most members, these meetings were the main, and sometimes even the only, entertainment in their lives. That’s why the attendance was good, although the small influx of young female participants was worrisome. Older people, accompanied somewhat less by daughters or granddaughters, predominated. It was feared that the society would die out in the future, but interest in it did not wane over the twenty-year period.

Our housekeeper Maria Olszewska, whom we treated as a family member, played a major role in the preparations for the “coffee”. She came from Czersk in Pomerania, where her family still lived and to which she went once a year on vacation. She was a few years older than my mother. She had completed housekeeping courses and served an apprenticeship in some aristocratic house, learning to cook under the guidance of the cook who worked there.

As far as I know, her arrival in our house made it easier for my mother to overcome the initial difficulties. Thus, mother valued her immensely and surrounded her with respect and cordiality. On the other hand, the housekeeper became so attached to our family, especially to our mother, that she felt at home here and treated us as her nearest and dearest. She loved all the children as if they were her own, but especially spoiled the youngest of us. In mother’s absence, she substituted for her towards us, as well as towards the servants. For some time, mother wanted to introduce the custom of calling her “Mrs. Marynia”. However, the servants called her “Mrs. Housekeeper”. The children called her “Gosia”. And so it remained.

We visited her regularly in the afternoon when Gosia was sitting in her room. She always had a tin of candy or cookies for us. While eating the candy, we would jump on her couch and ask her about various things. She chatted with us eagerly and told us interesting stories, giving us great pleasure. Gosia always remembered when someone’s name day. (Name days are a Catholic tradition of celebrating one’s saint’s feast day, historically more significant than birthdays in many European cultures). Gosia made sure that the gardener decorated the name day child’s chair at the table with greenery and flowers. She arranged the decorations around the plate herself. The menu consisted exclusively of the favorite dishes of the person celebating, who, coming to breakfast, found gifts by his or her seat. There always was a small trinket from Gosia among them. Without her, we could not imagine our home in Czernin.

Gosia helped our mother manage the servants, who consisted of four young girls. The maid cleaned most rooms, set the table, and served meals. The rest of the rooms were cleaned by a girl who watched over the youngest children and went for walks with them. She also helped the maid with washing dishes and some other chores. In the kitchen, the housekeeper was assisted by an elewka, an understudy. Although the understudy’s main task was to learn cooking and housekeeping, she was also paid. She was never commissioned to do menial labor. The kitchen helper did these jobs. She lit the fire in the kitchen stove, washed the pots, and cleaned the kitchen along with the hallway and kitchen stairs. She was also employed to raise poultry.

Mother was cautious that none of the girls was overloaded and that their daily work did not take too long. When they cleaned up after dinner, usually before two o’clock, the girls enjoyed time off until four o’clock. Some went for a nap, while others were sewing or knitting. After the break, they prepared afternoon tea, which was served around half past five. At seven o’clock, dinner was served, after which only the cleaning of the dining room, kitchen, and sideboard was mandatory. Mother always ensured that all work was completed by eight o’clock at the latest. In the summer, all four girls sometimes walked around the park in the evenings, often singing songs. Every other Sunday was free, rotating for two other people.

Once, while teasing during an evening wash, we spilled a pitcher of water on the floor. Not thinking much, one of us said: “I’ll call Martha right away to wipe it up”. Mother became angry and forbade us to call anyone. She sharply reminded us that the girls had worked all day and were now due to rest. She ordered us to wipe. However, we were still small, so she did the main part of the work herself. When our older brother learned about this the next day, he reproached us about how we could have allowed our mother to work so hard. He stated that we had shortened her life by at least a few days. This made a painful impression on me. I was reminded of his words in similar situations more than once later.