Table of Contents

- Warning

- Dedication

- Thanks

- Introduction

-

The Color of Your Mind

- The world created you as you are

- You change the world by acting upon it

- When you act, the world feeds back to you (cybernetics)

- On self-fulfilling prophecies

- Structural Coupling

- Your perception of the world is colored by your mind

- Two blind spots of your mind

- Consciousness and detection

- Summary of chapter

- Questions

- The Colors of Change

- Finding the Right Color for a Change

-

Change Approaches that Work

- NIH syndrome (“Not Invented Here”)

- WIIFM syndrome (“What’s In It For Me?”)

- Strength-based approaches to change

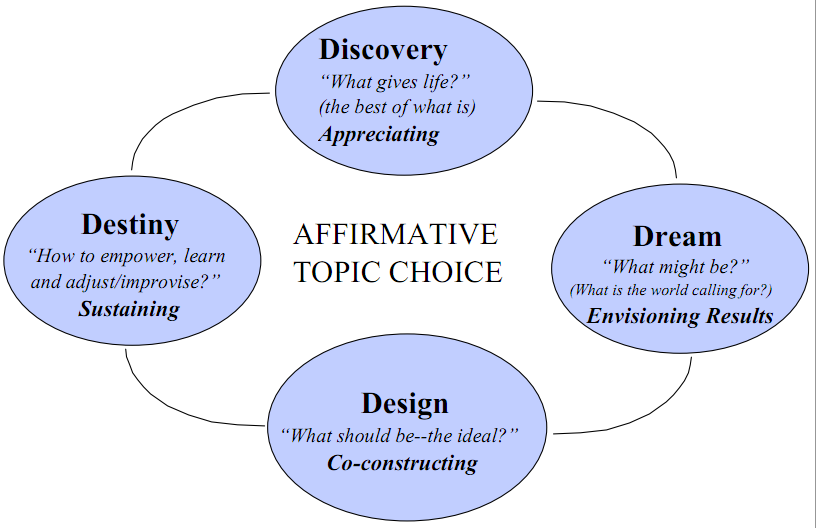

- Appreciative Inquiry

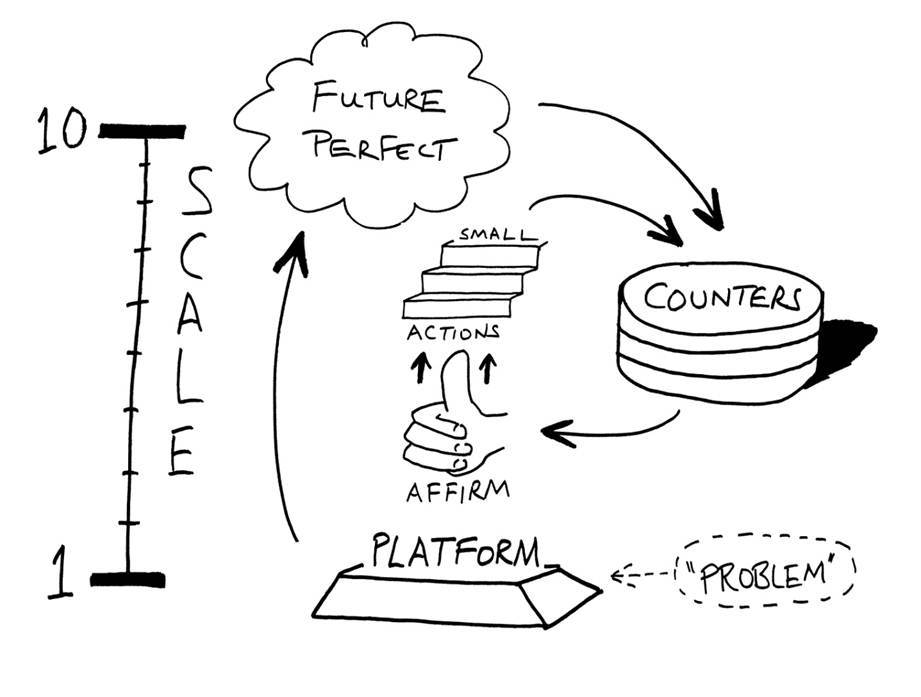

- Solution Focus

- Positive Deviance

- Storytelling

- Clean Language & Symbolic Modelling

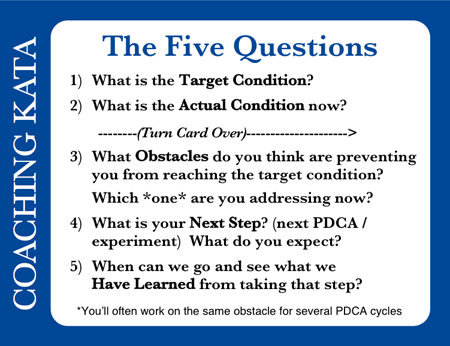

- Lean management

- General Semantics

- Carl Rogers

- Self-Determination Theory

- The World Café

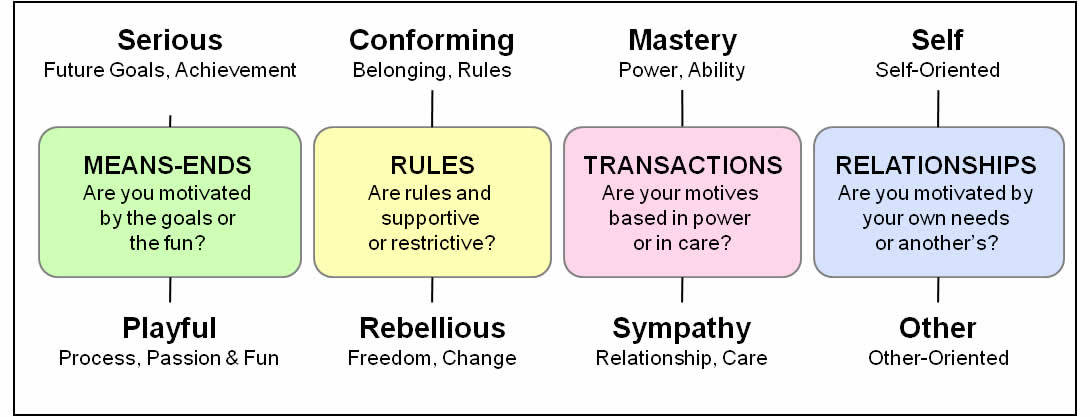

- Reversal Theory

- ADKAR©

- BJ Fogg’s behavior model

- Summary of Chapter

- Questions

- Notes

Warning

This work represents a few years of personal studies of a wide range of fields, roughly: lean management, systems thinking, strength-based change approaches, cybernetics, and an ounce of psychology.

I am not an expert in these fields in the sense that I don’t own a diploma from any of them.

Yet, I claim personal first-hand experience of that which is explained in this book, both in work and personal life, assorted of self-reflection on my part upon:

- what I witnessed;

- how my personal perspective could have shaped the meaning I attached to what I witnessed;

- what others might have witnessed themselves;

- and how their personal perspectives might have shaped the meaning they seem to have attached to their personal experience of the same event… given what I saw of how they expressed their meaning.

This is circular and I know it. Yet, this is precisely what I would like to talk about in this book.

I am a radical constructivist, which means that I’m convinced that I can only know the world out of my personal experience of it, and that I will (probably) never know for sure whether the meaning I attach to my personal experience of it is close to reality (what’s happening outside of my body senses) or not. I accept the fact that I might be totally wrong about what’s written in this book and that someone may have a totally different opinion of how things work.

Or maybe this is just the opposite? At least, as Solution Focus experts would say: it works for me, so I intend to continue on this line.

Bear with me :-)

Dedication

This book is dedicated to all the great systems researchers of life. Without their previous work, the insights I couched down in this book would never have been made possible.

Some earlier researchers took the systems of life apart to understand them, before knowing about systems. That was the first wave of insights into life.

Some more recent researchers took some more (w)holistic views of life and made different discoveries. That was the second wave of insights.

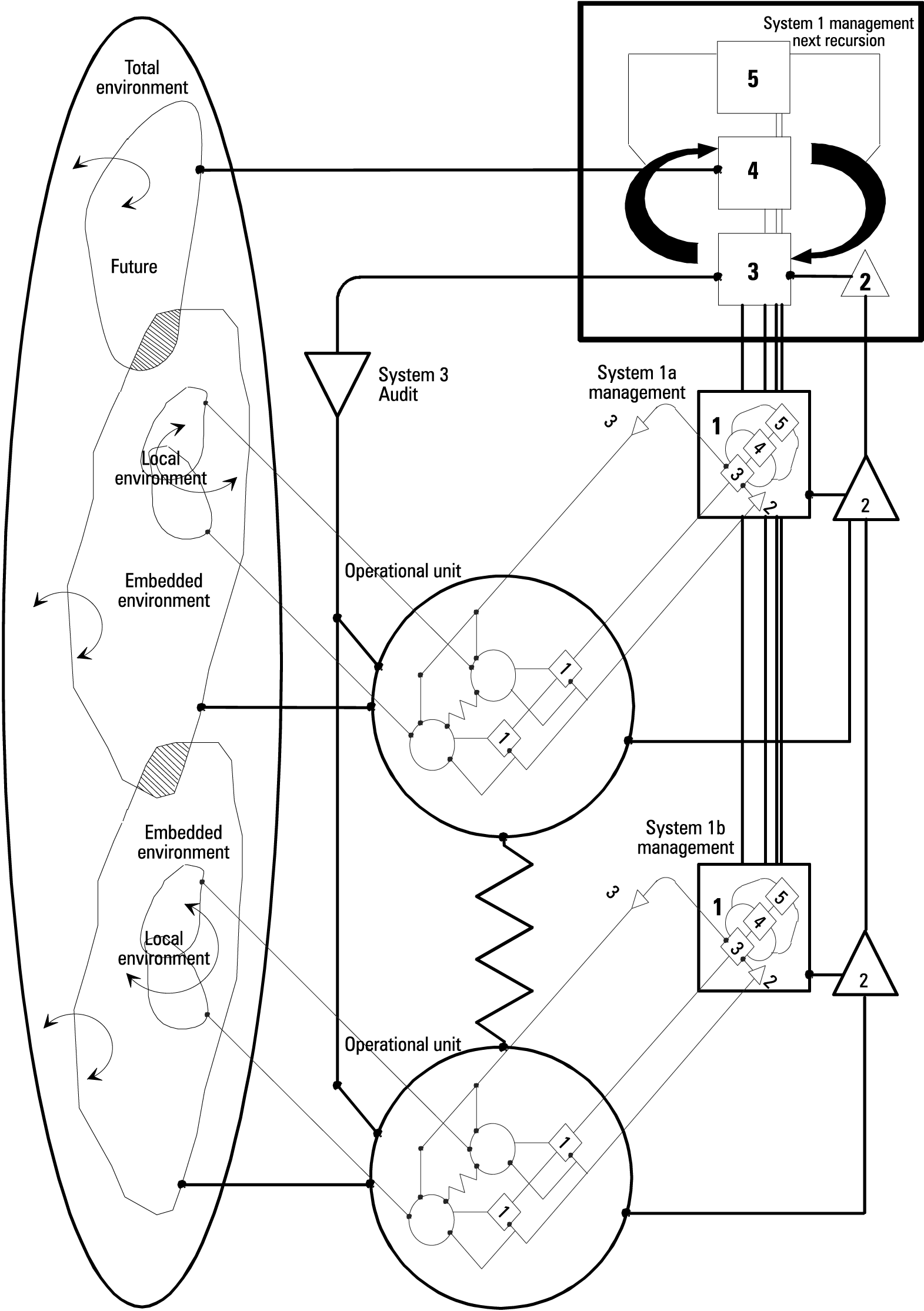

Then came “pure” systems thinkers that discovered that some of the previous insights could be generalized and were indeed applicable to other disciplines as well. They created a new science called “Systems Thinking”; the third wave of insights.

The latest wave of systems thinkers went so far as saying that we need to hold the three kind of insights in mind at the same time. As complex as this might be, I consider this to be a fourth wave of insights1.

This book builds on all four waves of insights. It doesn’t claim to be of a new wave, but only to check against all the preceding ones and tries to apply what I think might be the consequences of these teachings to the field of Change Management.

Thanks

This book would of course not have been possible without a host of other persons. Some are close, some are less (physically) close, but I feel close to them if only just because I feel like standing on their shoulders.

My family for having a sometimes (often?) dad and husband more in his head than at home on evenings. I did try to reinvest some of my systems and strength-based knowledge into family stuff. I don’t know if I succeeded. Honey? Kids?

Sallie Lee for my initial training in Appreciative Inquiry and infecting me with that benevolent virus: your workshop and training was so good that I felt like we, participants, were about to create an organization out of the Design and Deliver parts on the concept of “Trust”.

Michaël Ballé is the man that unwillingly started my journey in Systems Thinking. Indeed, I found out that he wrote a book titled “Managing With Systems Thinking: Making Dynamics Work for You in Business Decision Making “. Willing to know more, I asked him about Systems Thinking, only to be heard that I shouldn’t go that path because Systems Thinking is like “digging in sands: the more you dig, the more you find something”. Being someone I highly respect, I decided to go nonetheless… because I wanted to know more about his background, why he was successful, and also because I felt like he pressed my resistance button: how couldn’t I go that “dangerous way” against which he was warning me? I suspect he might have done this on purpose…

Franck Vermet for our phone exchanges and few meetings about how we could improve Lean to put back the “Respect for People” that should never have gotten out of it. Congrats for all the successful experiments you did in your plant: gemba+deep respect at the same time, all with a dose of gamification!

David Shaked for our excellent exchanges regarding strength-based change, and for his managing of the LinkedIn Strength-Based Lean Six Sigma group (http://bit.ly/SBLSSLI). David has a very soft and opened way of re-framing questions into a positive stance with Appreciative Inquiry and Solution Focus. A gifted guy! David is also the guy that made me start this book for real.

Jeremy Scrivens for his strong stance on Positive Psychology and Strengths and how he’s trying to mix that with more traditional Lean and Six Sigma approaches. Also, for mapping my own strengths and encouraging me in using them in all I do.

Gene Bellinger for his dedication to constantly updating his web sites (Systems Thinking World), YouTube channel, LinkedIn discussion group, InsightMaker models, etc. His dedication to making Systems Thinking known to a wider audience is commanding and humbling at the same time. I wish I were as irradiating as he is!

Alexis Nicolas for our regular exchanges and lunches around “all that work for us and how couldn’t it, damn it, work for others too, and what can we experiment to change that?”. Alexis, although a fertile ground beforehand, was my first turn-over to strength-based approaches. He consequently registered for an Appreciative Inquiry training (with David Shaked) which directly rushed him in the AI world in France and Europe. I look forward to the great things you’ll soon build.

Bernard Tollec for his energy engaged in making strength-based approaches a success in France (AI and SF) and in wanting, like me, to change the world all-at-once-on-a-as-global-as-possible-scale.

Members of the Systems Thinking World LinkedIn group for their numerous feedback and open mind when it comes to answering my questions, whether dumb in the beginning, and more obscure later. Did I really learned something with respect to Systems Thinking? They’ll tell you…

Members of the Strength-Based Lean Six Sigma LinkedIn group for the open-mindedness too and the wonderful exchanges in order to build a better approach to change in organizational settings.

My different managers for letting me experiment with all the stuff mentioned here. I probably wasn’t sometimes as efficient as they expected me to be, but I hope these investments in experimentations and learning did result in some lasting positive change in the organizations. At least I tried not to hurt anyone in the process…

And my colleagues for

- gently listening to me (sometimes during commute when they had the bad luck of sharing the same transport lines than me)

- letting me experiment on them. Hopefully it has been respectful… or so I hope to have learned a bit along the way… yes?

And finally to all people (most of them renowned in their respective fields) that published fabulous work. It inspired me and I borrowed from it without pity. I now understand what it really means to stand on the shoulders of giants. The view’s far better here when you make the effort to reach it.

Deep thanks to all.

Introduction

This book is about change management. But, unusual to such books, it won’t give you a new method to manage or lead change so as to overcome that so-called “change resistance”. Indeed, that book is based on the premise that the traditional ways to approach change are fundamentally flawed. What’s more, the traditional approaches to change are deeply ingrained in how our mind works.

I will use the science of Systems Thinking and Cybernetics

to explain why this is the case and what we can do about it. I will then review some proven and successful approaches to change that are as much respectful of people and their view of the world as can be.

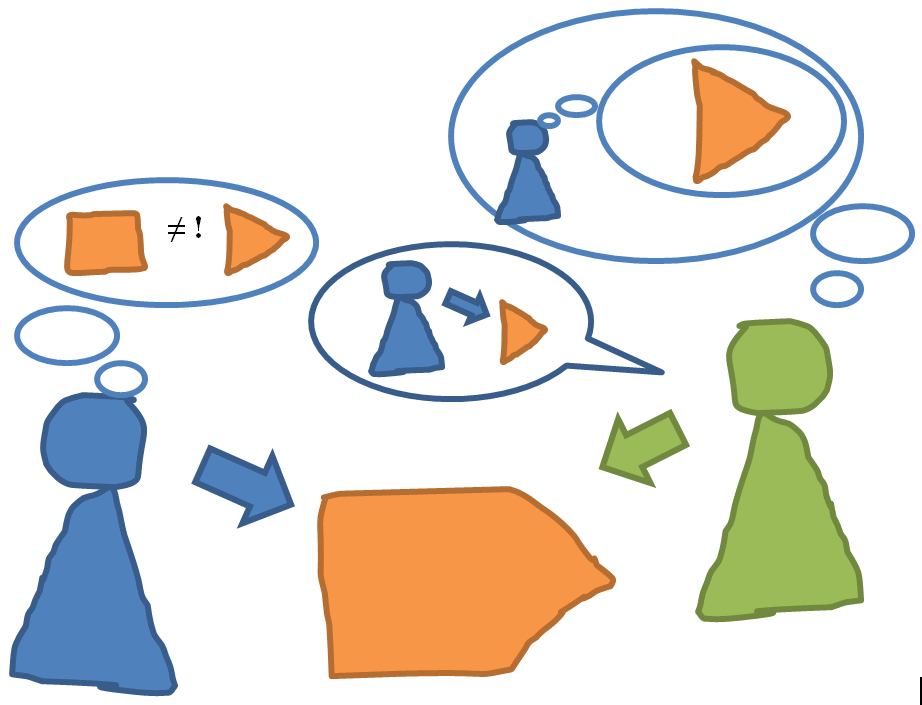

It is said that a picture is worth a thousand words. So here’s below a picture of what I would like to talk about in this book: what’s usually done that is not working, what consequences this has, why we keep doing it and what I propose should be done instead.

The Orange form is a metaphor for the work that is the target of the change.

Blue represents the people working with Orange all day long and who know best about it (at least on a first approach). To them, Orange is a square and whatever is said, there’s no way to make them change their mind about it. Indeed, would you like to make them consider the triangle part, they wouldn’t follow you as they don’t see the point of considering their square from another side given that they’re convinced that it’s a square. Furthermore, viewing Orange from a Square perspective has proven to work for them until now.

Green is the change leader. It might be the top management or some external consultant with an expertise on the field of Orange stuff. To Green people, Orange is a triangle from their own perspective.

There’s no point in arguing whether the truth is a Square or a Triangle or some other form. The fact is that a Blue or Green perspective provides a vision of Orange that is what it is to them, and, most probably, this perspective is the truth to them (for there may very be some reality behind that perception).

We can see that Green, most probably because of his position of power or expertise thinks that his vision of the situation is the right one and that Blue somehow agrees with it. Consequently, it asks Blue to change and act upon Orange as if it were a Triangle. Two consequences usually happen at this stage:

- Blue doesn’t perceive the difference between his Square and the proposed Triangle (doesn’t detect the difference in assessing Orange) and just goes on with the change plan. Once Green leaves, though, Blue will go back to how things were done before, because, unconsciously, his previous work habits better fit a Square than those imposed by Blue that were directed at an (undetected, unfitting) Triangle.

- Blue does perceive the difference between the blue vision of the Triangle and his own vision of the Square and just resist the change because the proposed image doesn’t match his view of reality.

Wrestling between Green and Blue occurs with most probably collateral damage (disengagement, valuable staff leaving, etc.) and, in the end, the situation either is worse than before or it ends up reverting to its initial state; the organization just lick its wounds and cries over its losses (people, motivation, finance, opportunities…): that was the change method of the month.

About the colorful metaphor

Some readers might wonder about the book’s title. There’s a small story behind it. As is clear to most people (and this book is indeed related to this), your knowledge is evident for you. But when it comes to explaining to others that don’t have the same background as you, it’s often difficult to ensure they understand what you’re talking about. It might be a construction of mine that I think people won’t understand me but then I usually try to take a lot of precautions to avoid giving too complex an explanation.

So one day it came that David Shaked and I exchanged on that topic of Change Resistance and here how it went:

— “Hey, I have this (e)book I’d like to write on the subject of change resistance, wanna hear about it?

— Sure, said David.

— Ok, so… err… hmm… (Damn, I don’t even know where to start!)”

So there I was trying to speak passionately about something that was filling my mind since quite a few months, and unable to utter a word (in a language that’s not my mother tongue, which furthermore didn’t help…) So I came up with this metaphor, and since it seemed that David understood it, I decided to keep it. Of course, it might be that David just smiled to reassure me and that he didn’t understand a word, and being a gentleman as he is, he would never dare to say my explanations were… lame? So here is what I came up with.

The metaphor

Suppose your mind is painted in just one color (say: blue). Whatever you see is always painted in blue, and whatever you do always has this blue color. This is your mental model: blue. It turns out that if people talk blue to you, you will fully understand them as they speak what you are able to understand. But as soon as they try to use another color ith you, you will immediately spot it since it is blatantly different from all you are accustomed to (blue). So this obviously has two consequences:

- You will immediately notice any color (of mind) different from your own,

- Any different color will appear “wrong” to you since you’ve always been raised in a blue environment. Your experienced truth is blue, so all things must be blue to be true.

It also turns out that if people want to show you things of a different color, you will either be blind to it (you’ll only see the blue parts of them, the rest will be blind to you) or you will reject it as being wrong (of the wrong color, true being blue ). So if people want to teach you to see things of another color, they have only two possible paths:

- Show you that even your blue as some different nuances and that what they propose also has these kind of nuances

- Or show you that what they propose, although of an overall different color, it still has some blue here and there and that it can connects with your own blue mental model.

Incidentally, A. just sent me this TED video showing how we sometimes misinterpret colors or how the context changes how we perceive colors. Literally.

Starting the book

There it was: all my wonderful theory in splashes of color. All I had to do now was to put it in words on paper. As I hadn’t the fainted clue where to start, David could have pushed me to start writing the book (indeed, he started one himself at that time). Instead, since he knows better than me, he gently coached me in a solution-focused way and our discussion went on that way:

David: — “What’s the smallest step you could do to start on your book?

— Well, I suppose I could just write down what I just told you (which I didn’t take note of, of course… bummer!)

— What’s an even smallest step?

— Maybe just jot some notes down?

— And an even smaller step?

— Maybe I could just create an empty file with a title?”

And there I was the next day: I had the current title in mind and I created an empty file with that title. I sticked a “version 1.0” at the end of it and that was the beginning of the journey.

Many, many thanks, David, I owe you much on this one!

So, I’m going to present hereafter the principles that David used to put me in motion in order to write this book.

What this book will talk about

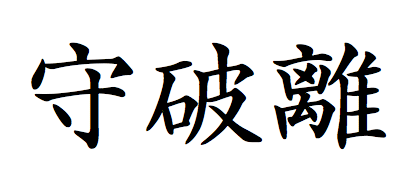

The Color of Your Mind sets the context. Here I explain how our mental model forms over time and what consequence this has on how we see the world, interact with it, and what kind of system this creates between the two (our mind and the world). Here is introduced the notion of cybernetics.

The Colors of Changes defines the problem. I explain how we see change, whether it is some change we would like others to be, or change that it imposed on us. I also explain why is it that most changes start wrongly (ie, provoke resistance), that it is a normal consequence of how our mind built over time.

Painting a Change of the Right color is where the principles of working solutions are exposed. This is the core of the book: how to address, manage and lead change so that it starts on the right foot, goes well along the way right to the end, when all’s done and everybody’s safe and happy because the change was respectful.

In Other Aspects of Change I will review some of the most often encountered problems with change, namely NIH (Not Invented Here) and WIIFM (What’s In It For Me?). I will also review a few well known change approaches, and explain how related they are to the model presented in this book and what we might do to improve them if we want to avoid changing these change approaches (!) too much. I will also review other approaches that I think are perfectly in line with the principles outlined here and that indeed seem to work better.

I have also provided some appendixes to allow you to deepen your knowledge about specific aspects.

Change Maturity Model is a tentative model to assess the maturity level of your change initiative in terms of respect, and how you can improve move up to a more mature level, ie. to a more respectful level of change.

The chapter on DSRP (Distinction, Systems, Relationships and Perspectives) shortly describes “The Minimal Concept Theory of Systems Thinking (MCT/ST)” as proposed by Dr Derek Cabrera and how to use it to propose a change or assess (and challenge) a change being imposed onto you.

I’ve put a lot of References in a last chapter so that you, dear reader, may also dive deep into highly interesting resources in order to stand on the shoulders of some well known giants like I feel I did.

A Few Questions

Each chapter will end with a few questions for you to reflect on. Here are the first ones after your reading of this introduction. Please write your answers for reading back at the end of the book.

- What does “respectful” mean to you?

- What does “change” encompass for you?

- What does “respectful change” mean to you?

- How “respectful” do you think you are when it comes to introducing a change?

- Does the word “complexity” strike a chord in you?

- How do you react to complexity: fight or flight? Something else?

The Color of Your Mind

How your mind is modeled by your past experiences

In this chapter we will start at the beginning: how your mind is modelled by your life.

All the knowledge you accumulated, your particular way of thinking, what you distinguish first in any situation, what you attend to, what motivates you, etc. make up that thing called a mental model. In short, all that which makes you who you are.

Every mental model is different from all others, because they are not you.

What we call “mental model”, others call perspective, view point or weltanschauung, a german term for worldviews.

The world created you as you are

When you were born, you were like a blank sheet of paper. Of course, you came with your own genetic pool, itself coming from that of your parents. But what’s important is that your brain, holding your mind, developed as you go.

In the beginning, unable to coordinate your own body, you were just a receptacle of sensory information. Steps by steps, your mind started to make sense of your environment. Indeed, your mind was modeled according to how it physically perceived the world.

And then you were able to interact with the world: first by catching objects near you, then babbling, then finally walking and speaking. Mostly out of first reproducing what you saw others doing.

Indeed, what’s important here is that the world shaped your mind or, metaphorically speaking, the world colored your mind.

From then on, you were able to interact with the world.

Yet as important as the preceding point is the fact that all you did not experience shaped you as well in the sense that your mind, although maybe aware of it, might not be as knowledgeable as if you personally experienced it. Another way to state this is what you didn’t experience (nor even came to know about) hasn’t had a chance to influence your mind, which makes you a very specific person with respect to it, with any possible attached benefits and drawbacks. Back to our metaphor, that which you don’t know hasn’t put any colored stain on your mind, for better or for worse.

On second-hand knowledge

Now, being able to “know about” something without experiencing it is both fortunate and a curse.

It’s fortunate (thanks to language) as it allows you to come to know about something and then let you decide whether you want that information to influence your next actions2 or not. Yet, that knowledge is rough since it’s second-hand knowledge (if not third-hand or more).

It’s also a curse because people tend to confound words or ideas with the things they represent3 . People tend to think that because they can talk of something or because they know about something, they have some knowledge of it and that somehow qualifies them to speak about it and let others think they have some sort of expertise of that something.

Surely, knowing about something makes them a different person than those that never heard of it.

Yet there’s a huge difference between surface knowledge and deep knowledge acquired through personal experience. And the more deep and recent personal experience, the more thorough that imprint is on your mental model.

A consequence of that is a manager shouldn’t assume he knows what the work really is like if he has not been involved deeply and recently in it. A parent should not assume he knows what kid’s life is because he was a kid before: the world changed since then, and the kids are not their own parents.

By exploring, manipulating and acting upon the world, you gain far deeper knowledge of reality that what can be expressed through words only4 .

You change the world by acting upon it

Of course, the relation between the world and you isn’t unilateral. As surely as the world influences your mental model, you too can influence the world by acting upon it. Indeed, there are two occurrences where you influence the world:

- When you deliberately decide to act, you influence the world. Whether that action will have a persistent effect depends on a huge number of factors not addressed here. This is the most evident way to influence or change the world.

- Also, when you fidget with the world to enhance your understanding of it, as described in the preceding section, you influence it as well! This kind of influence goes mostly unnoticed from you and others (since it’s of a limited impact) yet it does happen.

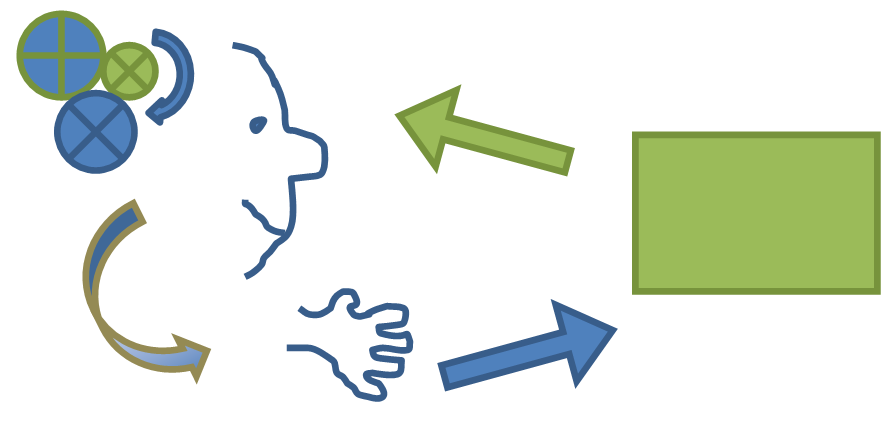

Indeed, we can start to make a first connection with the preceding section:

Or, stated more shortly:

And conversely:

So we can start to see how the world influenced us, and how we influence it back. Or the other way round. This is a circular affair and whether this turns out to be a vertuous or vicious circle is an important consideration to make. We’ll come to this point later and indeed this book is also about making sure that how we influence the world turns out to be for the good rather than for the bad.

When you act, the world feeds back to you (cybernetics)

Wait, don’t run because of the big words! I’m going to explain this one (cybernetics) and it’s really simple.

I probably stated the obvious in the preceding section. I’m not going to argue the opposite. Yet, there’s an important consequence I would like to stress now:

As soon as you start to act on the world, the world sends messages back to you.

Ah! Now you’re asking yourself whether I’m dumb or something, because you knew it already.

Well, what I really wanted to convey was the idea that :

The reaction you experience from the world when interacting with it is called a feedback. For instance, when you touch a very hot surface, you have a reflex to remove your hand: this is a feedback from your nerves to your muscles (indeed, this one even bypasses your brain). The first systems thinkers studied feedback systems and discovered interesting properties and they named that whole new science of systems and feedbacks “cybernetics”. As said in Wikipedia5 :

Cybernetics is applicable when a system being analyzed is involved in a closed signaling loop; that is, where action by the system generates some change in its environment and that change is reflected in that system in some manner (feedback) that triggers a system change, originally referred to as a “circular causal” relationship.

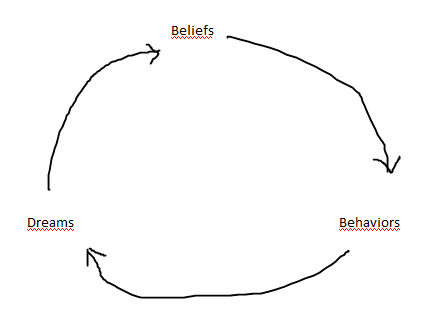

That constant feedback between your mind (your mental model) and the world means that there’s a deep, structural relations between the two, as pictured below:

Now you might wonder whether there’s a chicken and egg problem regarding which came first: the mental representation of reality that you decided to act upon, or reality that made an impression on you to which you reacted.

Well, I tend to think the question shouldn’t be asked that way. In fact your past experience of the world molded you (remember the beginning of the chapter when I talked about when you were a baby?) and that influenced your actions now, which will make the world react later. So it’s true that there are constant interactions between your mind and the world but that interaction is spread in time.

A note on delays

There’s a last note that I would like to make and it is related to delays. When you act on reality (whatever it might be), there are two things that might happen:

- You get instant feedback on your action (by way of senses)

- And there might (though this is not systematic) be some reaction triggered that may make itself visible to you only later… or not.

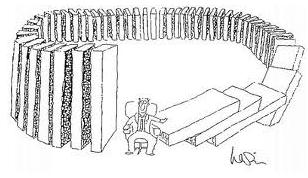

Cybernetics has lots of things to say on delays, but we won’t enter these considerations here. What’s important for our purpose is to note that sometimes we might be subjected to actions that is delayed feedback from previous actions we initiated (long) before. But since the original action from ourselves is far in the past, we usually forgot about it and/or don’t make the link between the two. This is illustrated below.

On self-fulfilling prophecies

WYTIWYG: What you think is what you get

Let’s continue in this exploration of mental models, the world and feedback in between. Indeed, we talked of feedback from the world onto you, but the opposite is true also: when the world “touches” you, you generally feedback to it.

There’s another aspect to feedback and cybernetics that’s important to notice here and is a direct consequence of the preceding section.

When confronted to a certain situation and provided we give enough time to think it through, we usually have more than one possible answer to it. The answer we choose depends on what we know of the reality we’re going to act upon (the mental model of it that we hold in our mind), and, consequently, what reaction (or feedback) we expect from it.

What you expect influences what you do.

And it turns out that most of the times humans are usually quick at (consciously or not) making assumptions about what triggered visible behaviors. Whether these assumptions were right or not is an entirely different affair. Remember the section on second hand knowledge? Here we are. If you want to know more, I urge you to read about the ladder of inference from Chris Argyris.

For now, I would like to focus on a specific consequence of the ladder of inference, namely what has been well studied under the expression “Pygmalion effect” or “self-fulfilling prophecies”. Quoting Wikipedia again6:

The Pygmalion effect, or Rosenthal effect, is the phenomenon in which the greater the expectation placed upon people, often children or students and employees, the better they perform. The effect is named after Pygmalion, a play by George Bernard Shaw.

The Pygmalion effect is a form of self-fulfilling prophecy, and, in this respect, people will internalize their positive labels, and those with positive labels succeed accordingly. Within sociology, the effect is often cited with regard to education and social class.

How can we explain that in simpler terms? Well, let me give examples:

- You encounter someone you never met before. He’s smiling and you find that person friendly. This makes you start the conversation in a friendly manner as well, thereby beginning a probably very fruitful relation.

- Suppose you encounter someone else who’s making a frown. Wondering what’s happening there and that this person looks like she’s against you, you answer in a cautious way, which triggers a similar behavior from the other person. Although a wide range of possibilities exist for the next exchanges, the beginning of the conversation looks a lot less encouraging than in the previous example.

But now for the funny part.

Coming back to the previous example, it could be that the person making the frown is well intentioned toward you, but she’s feeling sick, or has a personal problem of some kind to which she was thinking when you both met. Yet, your cautious reaction influenced her, made her wary and negatively influenced the beginning of the exchange in a detrimental manner.

Or, it could be that the smiling person of the first example was simply happy because she had the assumption that you were somehow naïve and that she intended to abuse you in some way. But since you were so friendly, she changed her mind and this was the beginning of a long and fruitful collaboration.

Or, because you’re feeling sick yourself, you tend to think the other one may have a similar problem as well, and you feel compassionate toward her. Acting accordingly, the person feels valued and answer positively to you.

Or… well, you get the point.

What conclusion can we draw from all of this? I see a number of important points here:

- Your mental model influences what you notice.

- What you notice influences your assumptions.

- Your assumptions influence what you do.

- Your actions influence others’ assumptions (just like it did for you).

And:

- You can’t know for sure others assumptions beforehand.

And:

- You can decide how you will act, whatever your initial assumptions might be

And now for the useful part: in the same way that the Pygmalion effect can be triggered unconsciously, you can deliberately make use of it!

Whatever frown or smile the other person is doing, if you take a conscious step to display some specific behavior in your encounter with that other person, chances are that they will react to it (indeed, there’s a whole field behind this called Neuro-Linguistic Programming).

- What if you deliberately made a frown when encountering the person?

- What if you deliberately smiled when encountering the person making a frown?

- What if you smiled always?

- What if you assumed you didn’t know and then took a welcoming stance to each and every encounter?

So it turns out that there’s a nice lesson here that always assuming the best intentions on the part of others is more beneficial to you than assuming the worst or even being neutral.

As Paul Watzlawick said: “you cannot not communicate”, so you might as well go for the positive, don’t you think?

Structural Coupling

Or: cybernetics consequence: a mind is perfectly adapted to its surrounding world.

Here’s the central point of this book. Or the beginning of it all.

Or, as Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela have explained (albeit with more sophisticated and justified explanations): you are structurally coupled with your own world. What does this mean?

Well, it means that there’s a circular relationship between your mind that drives your actions, which influences the world around you (including other people) which influences what you see, which influences your mind.

The main consequences that you can draw from this seemingly evident fact are:

- Every mind is different.

- The differences with other minds reside in the specific past experiences this mind has had.

- These past experiences explain how the current mental model makes meaning of the world. This, cannot be guessed or understood by someone else.

So the main lesson here is that it’s unlikely (indeed impossible) for someone to exactly know what someone else is thinking, what would suit him/her best, etc.

It means that in the same way someone can’t know exactly what’s the best change that would suit you best, you also cannot know exactly what’s the change program that would best suit someone else, lest an entire department or worse, an entire organization.

So it’s better to stop trying to push change onto people and better let people design the change that would work for them.

Your perception of the world is colored by your mind

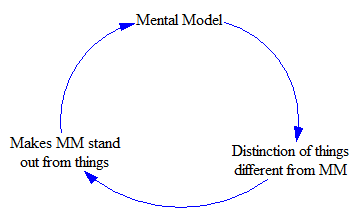

Then, as sure as the world colored your mind each time you’ve experienced it, the color of your mind influences how you experience the world on each and every encounter.

As your mind color taints your experiences, it reinforces its own color, on two accounts:

- Because it goes preferably toward those colors in the world that mirror its own (it distinguishes more easily in the world what it already knows how to distinguish).

- Because what’s pulled out of the world is preferably what is of the same color of it already, since this is what it can manage anyway.

And conversely…

Two blind spots of your mind

The previous section made the link between your past experiences and how you select present ones according to your current mental model (which I named “color of mind”). Indeed, the natural tendency is for the mind to reinforce what it already knows (ie reinforce it’s current color).

I’ve thereby stressed out two blind spots of our mental models:

- That to which we are so habituated it becomes oblivious to us.

- That which is so alien to us that we just can’t imagine and is therefore invisible to us.

What does this leave us with? Well, things that are not so habitual but which we are still capable of recognition because we (almost) continually put our conscious mind on them.

But beware: the more you put your consciousness to work on a subject, the more habituated you will become, and the more it will taint your mind, making it less and less obvious, thus unconscious.

Later in the book, we will study ways of making the unconscious back to consciousness. Although this isn’t a trivial affair, it is possible to achieve that with a bit of method, and this is a fateful thing to do.

Now we’ve seen what looks like two extremes of a continuum of consciousness, from unknown to all too well known. Now the question is: what’s in the middle?

Consciousness and detection

You might have thought that there’s some ambiguity in what precedes. I mean:

- Either you don’t know something, and I said it jumps to your consciousness when you first encounter it, or you just miss it altogether, totally blind to it.

- Or you know something, and you see it when you know it, or you so habituated to it that you don’t see it anymore.

It might appear like paradoxical only if you don’t know how to squint. When you squint, things that were one become two. That’s the case here, there are two different realities behind each proposition.

To make myself clearer, I would like to introduce you to the psychological explanation of the four stages of competences. Here’s an extract from Wikipedia:

- Unconscious incompetence: The individual does not understand or know how to do something and does not necessarily recognize the deficit.

- Conscious incompetence: Although the individual does not understand or know how to do something, he or she does recognize the deficit.

- Conscious competence: The individual understands or knows […] something.

- Unconscious competence: The individual has had so much practice […] that it has become “second nature”.

So how someone reacts to the world or to a change depends on the level of “competence” s/he has with respect to two aspects:

- What he’s doing now and the level of competence is has achieved in it (what he needs to change from) on the previous four stages of competence.

- What he’s supposed to do instead (what he needs to change to), again on one of these four stages.

Each stage mandates a different kind of intervention or management to be effective in moving things forward.

Of unconscious detection

The mind has the faculty to consciously direct its attention onto specific subjects of interest.

What’s implied is that what’s unconscious is in autopilot mode and can stay in the background for as long as it fits what the autopilot can manage, which means it must conform to behaviors as learned previously by the mind. As soon as what happens in the environment deviates from the mental model of the mind, an alarm is raised and consciousness is directed back to it.

So when it comes to unconscious knowledge, you only notice what’s different from your own mental model, which lets your mind available to focus on whatever you find interesting in the moment.

From here, we are bound to conclude that we have a natural (or unconscious) ability to spot differences between reality and what our mental model of reality is. So our mental model for this “difference spotting” revolves around:

- Doing this spotting unconsciously and

- The spotting has to do with differences between reality and our mental model.

What I really mean by the second point above is that we have a natural talent for spotting differences, and not similarities to ourselves.

This explains why we’re natural “problem” spotters and that we define a problem as anything that is not like what we expected [what our current mental model is] (whether we’re right or wrong in thinking it should be some thing or another is totally out of consideration here).

Of conscious detection

The preceding section dealt with how can we spot what’s different than our mental model. As we saw, this is pretty straightforward. Now the question is: can we spot what’s conformant to our mental model? Now, this is a tricky question.

Indeed, you unconsciously evolve in a world made up of your assumptions regarding how things should work and happen. When they do, you can conduct “business as usual” and don’t take too much attention to what’s going on. This is fortunate, as it allows you to go into autopilot mode and direct your mind to other activities.

But if we want to find a way to identify what you do right, we need to find a way to make the unconscious competence back to consciousness. How this can be done will be explained later in the book.

Summary of chapter

In this chapter, we introduced the following concepts:

- Structural Coupling between your mind and the world made you develop your own specific mental model of reality.

- Nobody can know exactly what someone else’s mental model of reality is.

- The best way to know about the world is to play with it.

- Yet how you interact with the world is influenced by your pre-existing mental model of it.

- This can have beneficial and detrimental effects through selffulfilling prophecies.

- Interacting with the world changes it.

- But the world feeds back to you as well (this is learning).

- Your knowledge of how the world works goes along a continuum of four stages of competence.

Questions

- What do you love to do?

- Where are you successful in what you do?

- What are others telling you excel in?

- How are the answers to the preceding questions different? How do you explain that?

- Think of a time where you convinced someone of one of your ideas. Was it difficult or easy? What argument won the exchanges? How could you have settled faster on a common position? Why wasn’t this option considered at that time?

- How did you build your current mind? What made you who you are now, with your current vision of the world? What have you learned to be “true”?

- What didn’t you experience personally about the world but you still know about?

- What new would living these unknown teach you? What would it teach you about you?

The Colors of Change

How your mind perceives change

In the preceding chapter, we set the context of how our mind builds itself over time. Or more precisely, how our mind and its surrounding environment or reality build themselves (are structurally coupled). The main conclusion was that our perception of the world, what I named our mental model always feel that its vision of reality is true and that the rest is consequently false.

This chapter now addresses the consequences of this context on how we perceive change. Indeed, this chapter will address the two cases of change:

- Change that you want others to do.

- And change that you’re supposed to achieve yourself (ie, change that is imposed on you).

But first of all, we need to work out some acceptable definitions related to change.

Definitions

Definition of Change

The compound definition given by a Google for “define:change” is as follow:

- change

- /CHānj/

- Verb Make or become different: “a proposal to change the law”; “beginning to change from green to gold”.

- Noun The act or instance of making or becoming different.

- Synonyms verb. alter - exchange - vary - shift - convert - transform noun. alteration - shift - variation - exchange - mutation

Definition of Change Management

The Wikipedia entry on Change Management starts as follows:

Change management is an approach to shifting/transitioning individuals, teams, and — in general — organizations from a current state to a desired future state. It is an organizational process aimed at helping change stakeholders to accept and embrace changes in their business environment or individuals in their personal lives.

I would like to stress out the last part of this definition which reflect exactly what this book aims to dismantle. Since Wikipedia is a communautary encyclopaedia, we can assume it somehow reflects what the majority of people think about a topic. The last part reads: “It is an organizational process aimed at helping change stakeholders to accept and embrace changes in their business environment or individuals in their personal lives.”

We can clearly see how common Change Management lore is about making others accept change. How respectful is that? In my mind, it is not. While if we are in a position where we must impose change onto others, I highly respect the traditional practice of change management to ease that necessary move that people must go through.

But this books aims at going much farther than that by explaining how:

- Forcing people through a change never is the best solution (neither for them nor for the change agent or the organization).

- Self-awareness about change can indeed much better address the changes organizations need to go through so as to respect all involved stakeholders and at the same time provide the best results for them all and the organiztion itself as a whole.

So for the purpose of this book, when I write about change, I mean the following:

This defintion is close to that of what Google gives, but I want to emphasize the ‘information’ part in addition to the action. As soon as someone gives some information, advice or hint to someone else with respect to how something should or even could be different, it’s a change and the first person is a change agent.

If you state a fact, it’s not change.

If you state something about a property that could be of a different value with the (stated or not) assumptions that the other value could be better, then you’re entering the field of change management, whether for yourself (no harm expected) or others; and this is the purpose of this book to address that aspect of change as best as possible, which is in a respectful way.

Definition of Respect

This book is about “respectful change management”.

Again, the Wikipedia definition of Respect is as follows:

Respect is a positive feeling of esteem or deference for a person or other entity (such as a nation or a religion), and also specific actions and conduct representative of that esteem.

When I write about respect in this book it usually means one or all of the following:

- a respect for the way people see reality from their perspective;

- a respect for experience people have or gained in a situation that is the subject of the change.

How the mind detects a need to change

As I have explained in the previous chapter, your mind built itself out of your past experiences. Out of this, it acquired some knowledge on how the world works, which spreads on a continuum from unknown incompetence to unknown competence.

What we are interested in here is how a need for change is triggered. When you encounter a situation that doesn’t exactly match what your current mental model is, you can make a distinction and separate that experience from you.

More precisely, what you detect are two situations:

- how the world is,

- how you expected the world to be.

What you do in such a case depends on context, but it mainly boils down to the following four possibilities:

- Change your mental model to adapt it to what you encountered in the world, meaning you abdicate to a change you perceive.

- Change the world to make it more conformant to what your mental model expected it to be, meaning you impose your change on the world.

- Go for a bit of the two possibilities, meaning you seek a compromise.

- Tenuki ie, do something else.

Change resistance

Why we always make the wrong step in change management

In the presence of a difference between your mental model and the world, it’s important to notice that your mental model is always right. Not necessarilly right in the sense of representing the truth, but right in the sense that it’s what represents you, who you are. You are at ease with how you think and how you see the world. It’s right from your own perspective.

Indeed, your mental model has a certain form of cohesion and acceptability to yourself that is built around a form of logical arrangement of all the parts of which it is made. Consequently that situation you distinguished in the world triggered a certain aspect of your mental model which is part of the whole. So it’s acceptable too.

Going further, what’s right (in terms of deontology or even with respect to some truth about how the world works) is always first considered from your own vantage point, which precisely is your current mental model.

So any difference you might spot in the world with respect to you triggers some part of your mental model, which also triggers your mental model as a whole through that logical connection and thus reinforces that whole as being a whole and, consequently, as being “true”. After all, you did live your life up to now with that whole, and it worked for you, so how could it be wrong?

Going back to our colorful metaphor: if your mind is a painting of some uniform color, should I make a drop of some other color chosen by me, it will surely be different from that which makes up your mental model. Consequently, you cannot not see it.

Talking of versus Experiencing reality

Indeed, the deep meaning we attach to words differ from one person to another. It’s probably not an issue for casual, everyday life. Yet, this invisibility of the deep meaning we attach to words and the corresponding assumption that we do share meaning ingrains itself in our mental models too. It’s only when we try to talk over the details of something that we bump into communication problems7.

There’s a saying that goes like “People always, always, always do exactly what makes the most amount of sense to them”8.

So it turns out that the person having the initiative, or the power, or the authority (or thinking she has any of them, whether true or not) most naturally wants to state her position with respect to the difference between her mental model and the world. And this is a natural thing to do since:

- She thinks she has some form of legitimity in stating her position

- Her mental model is right from her own perspective.

Why wouldn’t she act that way? Indeed, isn’t it what we all do in similar situations?

And this is exactly where the drama starts because at the very moment someone states that her mental model ought to be followed, she immediately reinforces the distinction between hers and yours. The more she will then explain why her mental model is right, the more you will distinguish in her explanations what precisely makes her mental model different from yours.

And guess what? It’s your mental model that’s right! Of course it is!

The quick solution to this problem is then evident: don’t do that. I mean: don’t push your mental model onto others. We’ell see in the next chapter how to better lead a change that is therefore respectful of both yours and others’ mental models.

Change others impose onto you

The intention behind the writing of this book was to never have to such a situation where you’re imposed a change that you feel you’re going to resist, for whatever good reasons you may have (and as we’ve seen in the previous section, your reasons are always good from your own perspective).

Unfortunately, this is deemed to still happen quite often. What can we do? Indeed, what your natural first step would be in such a case? Let’s review a few of these common, wrong, steps:

- Lecture people on the good way to conduct change (like giving them a specimen of this book or some other method you might prefer)

- Explain people why their change is bad and what ought to be done instead

- Go on guerilla mode and 1) resist their change 2) advertise your own way of seeing the change to stakeholders 3) lead the guerilla yourself (“if you want something done right, do it yourself”)

- Ask about the root causes and reasons for the change to be that way (in order to counter-argue them)

- Complain to your manager

- Complain to the other’s manager

- Abdicate and follow the imposed change

You didn’t really intended to take any one of these steps, did you? Yes? Oh well.

Let’s review each of these individually and see what’s wrong with them.

- Lecturing people on how to lead change.

- By lecturing people, you convey the implicit message that their way of conducting change is wrong and that you know better than them. Although I can’t really blame you if you really would like to advocate the approach stated in this book, I think it’s a bad move. Indeed, you’re going to provoke the same resistance that the change agent just provoked in you. Reasons for imposing a change are diverse though we most often encounter:

a) a lack of time to do otherwise,

b) a lack of confidence to go check all stakeholders,

c) a lack of a method to efficiently go around all stakeholders,

d) a lack of solid understanding of how change works,

e) any combination of the precedings, plus a few more.

Whatever assumptions you make about what the real reasons for imposing the change might be, lecturing will only make the change agent resist because she will want to make her case more preeminent, assured that she is that her vision is righter than yours (she’s the change agent, and you’re not). The more you expose your case, the more she will want to show off how her case is better than yours. This is a bad move, try another item from the list.

- Unseat their change and propose yours.

- In this case you have the same problem as in the preceding option. Any other way to go for the change would just provoke a resisting reaction from them. That’s probably the best case scenario; the worst case would be that they assign you to lead the change, only with just the remaining time and resources available to lead it. Which would mean you have less time and resources than they initially had, to wrap your mind around the problem and propose something. Chances are that you will have no other choice than imposing your own ideas to stakeholders. Go back to the preceding list and expect them to react with one or more of the items listed… Bad move, you failed.

- Go on guerilla mode.

- Apart from stating the obvious that it’s bad practice in work situations, this proposition would probably create a big mess at work. People will be lost between the “official” change initiative and your own. Some synchronization need will appear and people will sweat more stress and work to accomodate the two. Management will probably get upset and by the time they’ll find out who set the mess up, you’d be grilled (and so will probably be the initial change agent too for not having planned and managed the mess in the first place). The department is now a mess, you have a new enemy (if not the rest of your co-workers) and you’d probably get fired for that. Further, you probably triggered a second wave of resistance and then people might feel like they too are entitled to state their own way to the change. Bad move, go back to the list.

- Ask about root causes to unseat them.

- Although this approach may appear more thought through, it’s still not a wise shot. You run the risk of agreeing with the root causes of the changes but still disagreeing with how they should be solved (start over with the list above), or, you might disagree with the root causes, in which case advocating for other causes is just stating a different mental model. In other words, this is going for a clash as well. Start over with the list.

- Complain to your manager.

- If your manager approved the plan it usually means that he agreed with it. So the plan’s supporting mental model is now part of his own, meaning you’re about to clash with your boss’ mental model. Do you really want to do that? If you boss disagrees with the plan but accepted it nonetheless, your intervention will be perceived as a request for him to go for a clash with other managers, including his own. If he accepted the plan, it means his mental model features a part that says “don’t clash with management”, and, with your complain, you come in conflict with it. Bad move, go back to the list.

- Complain to the change agent’s manager.

- Well, what have been said previously for your own manager also counts for someone else’s manager. The difference is that you end up with more enemy than if you had just complained to your own manager: the other manager, all the hierarchy of management above your own manager and the other one. And since you upset so many people, chances are that you manager will be mad a you too. Guess what? Start over with the list.

- Abdicate and follow the imposed change.

- This is what a lot of people do in most organizations. This probably is the safest move to play when you more or less consciously think you expose yourself to risks by taking any of the other preceding moves. The situation more or less is the one described in the introduction of this book: on surface you seem to accept what the change agent says you must do, but the more you do it, the more it will probably clash with how you see your work or how you think the change should have been done. As soon as the change agent will leave, you’ll probably go back to doing business as usual. This was a bad move, but now you have no other choice in the list.

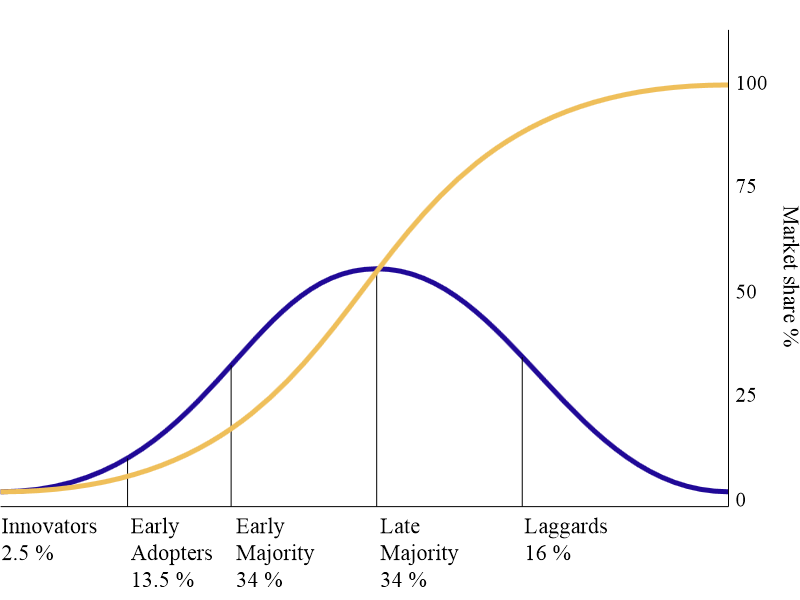

Of course, there’s a case I haven’t addressed at all: this is the case when you find the change to be indeed good. Unfortunately, it happens only rarely. If you did accept it, it probably means you’re part of the Innovators or the Early Adopters as featured in Rogers’ innovation curve.

Of course, in the next chapter of this book, we’ll see how to avoid this curve entirely and turn all of a population into Innovators and Early Adopters. Stay tuned.

What to do when being imposed change

After all these possible bad moves when being imposed change, it’s time to review a few of possible better moves (the underlying principles will be thoroughly detailed in the next chapter).

- As a first move it might be good to inquire for the reasons for the change: why is it that someone wants you to change, and what’s the reason for the change. The purpose is to go beyond the solution that might have been thrown to you and inquire into the more general expected outcome.

- Then it might be good to (genuinely and not rhetorically) inquire as to why the proposed solution might be a good one and how the change agent is going to measure whether the solution is going to yield the intended results…or not. Asking about the rationale that connected the goal and the solution (meaning this solution is supposed to help reaching this goal) will give you more information about the change agent’s mental model and his own vision of the world.

It’s only after these preliminary questions have been asked that you can start to reflect about how the change plan and underlying assumptions may match with your own vision of reality. If, on first sight, you don’t see any significant discrepancy between the change agent’s mental model and yours about how things should be done, then, let go of the “NIH syndrome” (Not Invented Here, click to jump to explanation, later in the book) that was triggered by the change agent’s not having flattered your ego first, and go for the change as it has been presented to you. Wait for things to turn wrong before coming back and trying to influence the proposed solution, with sound statistics to back up your proposal. Who knows? The initial change agenda could turn out to be working in the end, meaning that they indeed had a better perspective than you.

If the proposed solution doesn’t fit your own mental model (notice that I didn’t say it was wrong), use the following hints to clarify the situation and let the change agent know his perspective of the world is neither prevalent nor the only one:

- Always state that you describe the situation from your own perspective and that you might be missing some important data, but that you’re willing to be filled in the blanks.

- State what the situation is from your own perspective: what you think belong to the problematic situation, and what doesn’t.

- State what the problem is from your own perspective: what you think should be addressed in place of the proposed plan, or in addition. It may even be that part of the plan is supposed to address something that’s not a problem from your own perspective. Do state it.

- State what relation(s) you think are missing in the proposed plan between components of it (techniques, organizations, people, etc.) State how some relations in the plan might be different than what’s assumed, from your own perspective.

- State what component is missing from the plan, or should be excluded (and for what reason).

As a rule of thumb, use the following quick-n-dirty DSRP9 process to review the proposed plan.

- Describe the proposed plan using DSRP aspects: Distinctions, Systems, Relationships, Perspectives.

- State your own Perspective: position, knowledge…

- Review each of the proposed plan’s D, S, R, and P and see how your own Perspective might change the vision that the plan proposed.

- Assess whether some other Perspectives might benefit to the plan (typically: other stakeholders’ view). If relevant, find a way to involve them to get first hand knowledge about their own perspective (as a second choice, you can make hypotheses as to what their perspective might be – though you might want to be wary of second hand knowledge).

- Assess the differences between the two Perspectives, and see how a new plan might be proposed that would embed the best of all Perspectives.

- With all your complementary informations collected, ask the change agent whether she’s interested in some improvements to the plan in order to raise its chances of being properly implemented with as few as possible unintended side effects.

- If the change agent is interested, make documented proposals (ie what you proposed to change to the plan according to the preceding analysis, and the reasons for those changes to the initial change plan) and what improved outcomes might be expected.

For a more thorough usage of DSRP to propose and review change, see Appendix on DSRP.

For the parts of the change plan that you think are not implementable as-is, you might want to ask yourself one last question:

- “When considering that non-implementable part as a constraint, how can I achieve the intended results, in my own way, and still respect the constraint?”

In all cases, you might want to document, publicize and trace your analysis of the initial change plan and any reservations you might have had as to possible misfits and/or unintended consequences.

Change you impose onto others

As a rule of thumb: don’t impose change onto others.

Let’s make it clearer:

Ok, now why shouldn’t you want to impose change onto others?

As I have explained in the preceding sections, our mind constantly adapts itself to the world it encounters, and his interactions with the world constantly make it adapt to itself. As a consequence, being totally adapted to the world around you and the mental model you have of this world, any difference you spot between your mental model of the world and what someone else might say or do is going to trigger an alert for a difference. That difference might be resolved in only three ways:

- Rejected as being unimportant with your mental model and the situation being left unchanged.

- Accepted as legimitate with you updating your mental model.

- Rejected as “false” your mental model not being updated; instead a change is sought to modify the world to make it conformant to what your mental model says it ought to be.

The fact is that the first and third options are the ones most probably automatically triggered, because they don’t need a lot energy to be dealt with: they occur mostly unconsciously. The second one I won’t address here because that’s not the point and it somehow has been addressed in the preceding section.

The third option really is what’s interesting here. We saw previously that the cybernetics relations between the world and our mental model most often make us think we are right and others are wrong because:

- we’ve always lived with our mental model, so it’s right by definition,

- there are self-fulling prophecies at play that, if we don’t take care enough, tend to make us provoke the things we believed in in the first place, thereby masquerading to us what reality really is or might have been.

Still, I hope I have by now given you enough material in order for you to calmy assess whether what you think really is right and that, should you be convinced it is, whether others might think like you or not, and whether they might need time to adapt their mind around that idea for change you’re about to propose them.

I don’t have much else to say here as I’m going to explain how to conduce respectful change in the next chapter. By respectful, I mean a change that is both respectful of:

- your own ideas for the change,

- other stakeholders’ ideas involved in the proposed change.

My own wish for this section is that you are convinced that imposing a change onto others is never a good idea for the following reasons:

- What you have in mind regarding how to conduct a change only reflects your own mental model of the situation.

- Your own mental model is only adapted to some part of reality and that it cannot know in details what are others’ perspectives on the change you would like to achieve.

- Further, in case you’ve inquired into how your possible solution might work, you probably triggered a self-fulfilling prophecy that made you believe that what is needed is what you’ve inquired into. This is a very probably false assumption.

As a rule of thumb, each time you would like to change others, first take the deliberate step of inquirying into others’ perspective on the change and only after do take a decision in the light of what you discovered. On the worst case, it will have informed others of the change to come. On the best case, you will have learned something new that might make you revise your initial plans and therefore make a change that will be more respectful.

Before moving on to the next chapter, there are two traps I would like to address: that of being rhetoric only and that of setting up double-bind situations.

First trap: being rhetoric

This first trap I fell often into. And I sometimes still find myself about to fall into it. Despite knowing all the preceding about cybernetics and mental model formation, despite willing to genuinely know about others perspective about some change, we still ask very bad questions.

The questions we ask regarding others’ perspectives on change are often “rhetorical questions”. These questions often take an interro-negative form like “why don’t you do X?” or “don’t you think doing X would be a good thing?” These questions are bad because they are ressented as if you were trying to force a change agenda onto the people being asked. The chances of them resisting you are high because they will be felt like their ego has been trampled. Here are two tricks to help yourself in asking more genuine questions:

- be sincerely interested in knowing what they think of the change idea (and not about your solution),

- don’t ask interro-negative questions.

Some rules of thumbs for doing that are:

- State your mind first: if you have an idea for a solution, tell them, and frankly ask for their opinion about it: “I see a need for change in order to move from X to Y. What do you think of it?”. Then bear with their answer.

- If you want to know why they do certain things and not others (that you feel would be more appropriate), then only ask about their reasons for doing what they currently do: “Why are you doing X?”.

Now if you really want to know what other ideas they might have for doing things differently, then it means you’re ready for the next chapter about how to do respectful change.

A word of caution for managers: beware of people hiding their true opinions because they don’t want to be rude to you as their manager. If you suspect people might hide their opinions from you, then don’t make a self-fulfilling prophecy come true and don’t ask for their opinion on something that they might think come from you. Definitely bury your idea and just ask for their own solution. Trust them, chances are that they will come up with something surprisingly appropriate for the situation. If they do lack some information to make an informed decision, then provide that information to them.

Second trap: double-binds

My personal research in the work of great cyberneticists made me realize that the double-bind theory10 is probably more often at play in organizational settings than we might have thought, with the unintended effect of making people resist change in a very special way: by avoiding it, consciously or not. This sometimes is referred to as “passive change resistance”.

Quoting Wikipedia on Double-Bind yields the following:

A double bind is an emotionally distressing dilemma in communication in which an individual (or group) receives two or more conflicting messages, in which one message negates the other. This creates a situation in which a successful response to one message results in a failed response to the other (and vice versa), so that the person will be automatically wrong regardless of response. The double bind occurs when the person cannot confront the inherent dilemma, and therefore cannot resolve it or opt out of the situation.

Let me quote Gregory Bateson more extensively in explaining the necessary conditions for a double-bind situation to occur. In the following excerpt, “love” has to be replaced by “recognition” and “child” is “the victim”, the person that is expected to change. In the context of organizational setting, the victim is the person that is supposed to make the change, and “the parents” are played by management.

Bateson gives the following six necessary conditions for a double-bind to occur:

- Two or more persons. %%Of these, we designate one, for purposes of our definition, as the “victim.”

- Repeated experience. %%We assume that the double bind is a recurrent theme in the experience of the victim. Our hypothesis does not invoke a single traumatic experience, but such repeated experience that the double bind structure comes to be a habitual expectation.

- A primary negative injunction. %%This may have either of two forms: (a) Do not do so and so, or I will punish you,” or (b) “If you do not do so and so, I will punish you.” Here we select a context of learning based on avoidance of punishment rather than a context of reward seeking.

- A secondary injunction conflicting with the first at a more abstract level, and like the first enforced by punishments or signals which threaten survival. %%This secondary injunction is more difficult to describe than the primary for two reasons. First, the secondary injunction is commonly communicated to the child by nonverbal means. Posture, gesture, tone of voice, meaningful action, and the implications concealed in verbal comment may all be used to convey this more abstract message. Second, the secondary injunction may impinge upon any element of the primary prohibition. Verbalization of the secondary injunction may, therefore, include a wide variety of forms; for example, “Do not see this as punishment”; “Do not see me as the punishing agent”; “Do not submit to my prohibitions”; “Do not think of what you must not do”; “Do not question my love of which the primary prohibition is (or is not) an example”; and so on. Other examples become possible when the double bind is inflicted not by one individual but by two.

- A tertiary negative injunction prohibiting the victim from escaping from the field. %%In a formal sense it is perhaps unnecessary to list this injunction as a separate item since the reinforcement at the other two levels involves a threat to survival, and if the double binds are imposed during infancy, escape is naturally impossible. However, it seems that in some cases the escape from the field is made impossible by certain devices which are not purely negative, e.g., capricious promises of love, and the like.

- Finally, the complete set of ingredients is no longer necessary when the victim has learned to perceive his universe in double bind patterns.

There’s another worthy note to make about the fact that it’s not important whether management deliberately sets up the double-bind through conflicting messages: it is enough for the victim to understand and believe the messages to be conflicting, as well as believing s/he can’t escape the field. All this is implied by Bateson in point #6.

How does the theory of double-bind translate into management stuff? I am most concerned with double-binds in the canonical form of “be spontaneous”, where the victim is asked to be spontaneous, yet the very act of asking this question denies the possibility of spontaneity. If the victim doesn’t act, she fails. If she tries herself at being, she also fails because it’s not spontaneous. In a management-employee relationship, avoidance of this situation is further impossible11, which completes the conditions of the double-bind.

My bigger concern is when management asks a form of “change spontaneously!” to employees. Let’s take the six points again and see how they transpose into organizations:

- Two or more persons. We can identify two kind of people for our explanation, mainly management and employees, the latter having the role of “victim”.

- Repeated experience. There is ample evidence where management requires employees to do things with the – stated or not – assumptions that is should have been done spontaneously.

- A primary negative injunction. What we often see in organizations is management asking that a change be made. This often takes the form of “stopping” something that’s not working (bad quality, too long delays, financially unsustainable, etc.) and doing something else instead. What’s important here is that the “what to do” is told by management in the form of solving a problem or not to do the problematic things anymore.

- A secondary injunction conflicting with the first at a more abstract level. This secondary injunction may or may not be verbalized as an assumption from management that employees are supposed to know how to do that, but since they aren’t doing it, they’re not capable.

- A tertiary negative injunction prohibiting the victim from escaping from the field. This one is almost always implied in an organization: do as I said or leave / forget about your bonus / raise / next interesting opportunity / etc.

- Finally, the complete set of ingredients is no longer necessary when the victim has learned to perceive his universe in double bind patterns. It’s all too common that employees are wary of management’s requests, so that kind of learning already has occurred.

We can see from the preceding parallel between the theory and organizational settings that all ingredients are present for the double-bind to occur.

To what extent does this situation impacts employees probably has to be researched, but one of the most probable consequence is an avoidance behavior from workers when it comes to change that is imposed on them: that is, employees passively resist the change by not devoting energy into it.

Going back to the “be spontaneous” example above, if a manager makes a request to an employee with the stated or implied (and felt) assumption that the request should have been spontaneously fulfilled, then he’s setting up a double-bind. The most probable reaction to the employee in this (unescapable) situation would be an “Aye, Sir!” answer without further much work on the request, pretexting other more urgent and important work to do in place of the injunction.

Furthermore, work that a manager feels should have be done spontaneously usually quickly falls below that manager’s radar and few, if any, follow-up will happen, making it a de facto lesser priority when compared to other work requests.

The next chapter will address the solution to all these problems, namely: how to successfully lead change in the most respectful possible way.

Summary of chapter

In this chapter, we introduced the following concepts:

- Change resistance comes from encountering mental models that differ from our own and is thus a natural thing from a cybernetics perspective.

- Consequently, being imposed change is a natural (however unpleasant) thing. In such a situation, the best moves are to inquire into the reasons for the change and check whether your own perspective has been properly taken into consideration.

- DSRP (Distinction, Systems, Relationships, Perspectives) is a useful framework (to be detailed in a later chapter) to inquire into a proposed change.

- Wanting to impose change onto others is also a natural thing to do, although now you know you should refrain from it. Indeed, we learned that our own perspective is always incomplete when it comes to confronting it with that of other stakeholders of the change. So we need to inquire into theirs.

- Two traps to avoid: 1) being rhetoric in your inquiries into others’ perspective and 2) setting up double-bind situations that provoke passive change resistance.

Questions

- Go back to what you answered at the end of the Introduction. How was your vision of change and respect different or similar to the ones presented here? What conclusion do you draw from that?

- Think back to some changes you had to lead that people were resisting. What was your position? What was theirs? Who was “right”? How was the other party sure of the rightness of their position?

- When the change was over, how much of the initial plan got implemented? What is resisted at first? If it has been changed, in what way? How has the changes to the initial change plan been devised? What made it a better change plan to be implemented?

- Think to your habitual way of leading change: what you are used to saying, how you behave, etc. and compare with the double-bind criteria. How many of the six criteria do you meet? What does it tell you about yourself or your conception of the world? What might be different? How?

Finding the Right Color for a Change

Doing change right without raising resistance

Ok, here we are. We started this book by stating a situation in the introduction (misunderstandings between a blue worker and a green change agent, whether s/he is the manager or an external consultant). Then we discussed the context of how our mind builds itself over time and how it is structurally coupled with its environment, how the environment also feeds back to it, and how the mind selects or provokes in the environment what it’s already adapted to (self-fulfilling prophecies). And then we stated the problem we face when encountering a need for change and discovered how it is natural for the mind to resist a change for which it isn’t adapted or how it is natural to wanting others to change.

Now it’s time to study what possible solutions exist to avoid triggering resistance and, therefore, embark people (ourselves included) in respectful change management.

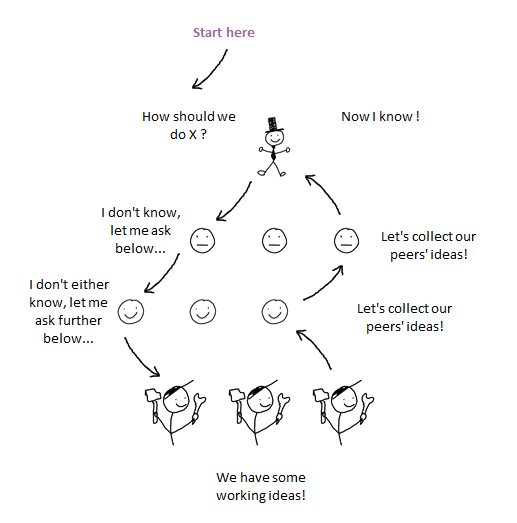

In my metaphorical lanscape, that would be finding or co-creating the the right color for everyone involved in the change.