Chapter One - A Brief History of Voting Machines, Certifications, Mail-In Voting, and Electronic Poll Pads

“There’s no way we can ever trust a computer system built with components made overseas, particularly in China, or assembled in China, let alone both, and that’s what we have in our voting system, unfortunately.”

—Col. Shawn Smith, USAF, Ret. – 25 year Air Force veteran and the former director and test manager for the operational testing of complex, computer-based weapon systems and a subject matter expert on the security of computer-based election systems, calling into a Tarrant County, Texas meeting

In the first place, how did we get to using machines, and electronic voting machines, in elections?

Before voting machines, voting was often done by voice throughout the 1800s. Kentucky used voice voting until 1891. The first paper ballots arrive in the early 19th century.

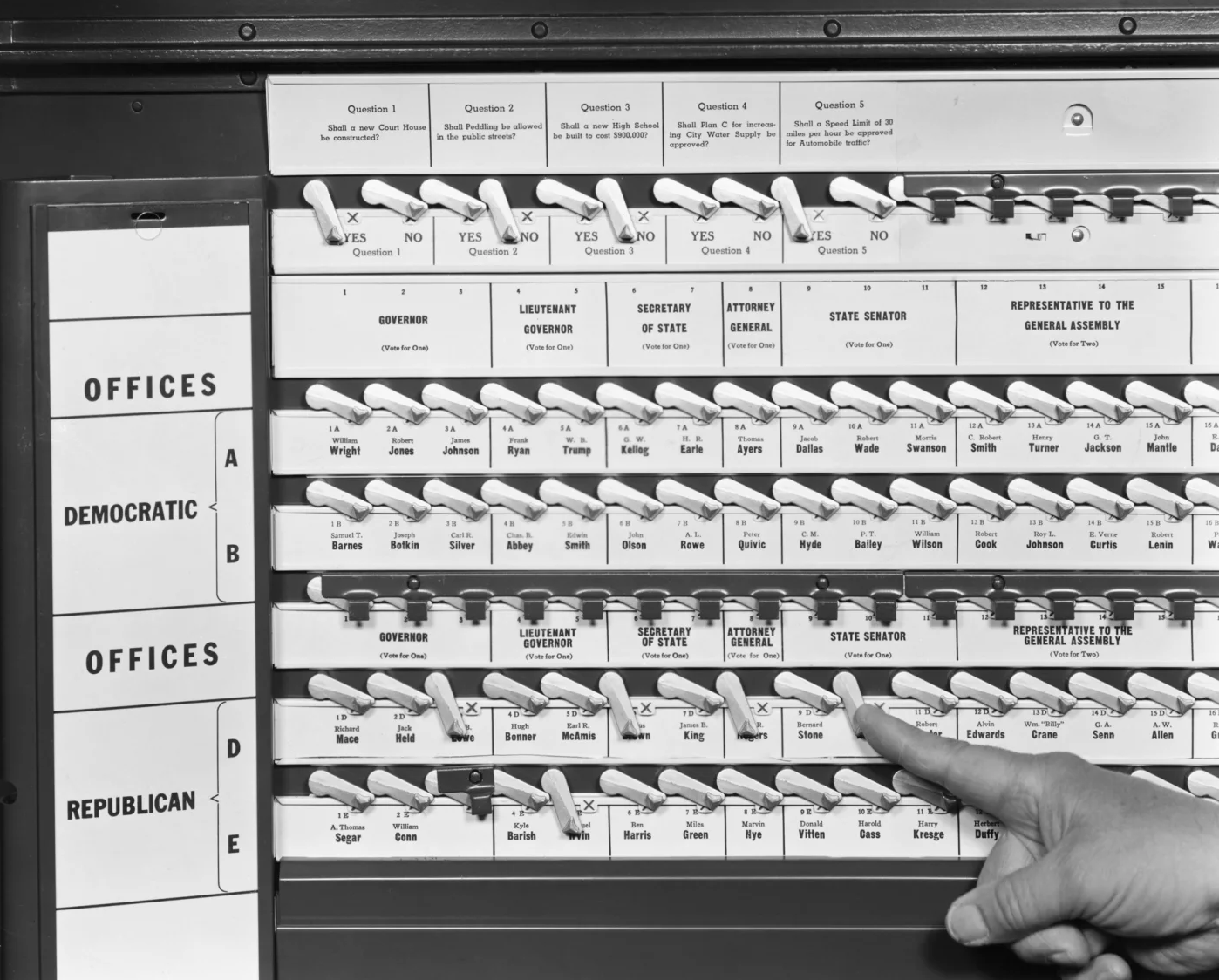

Then came voting machines: first lever, then punch cards.

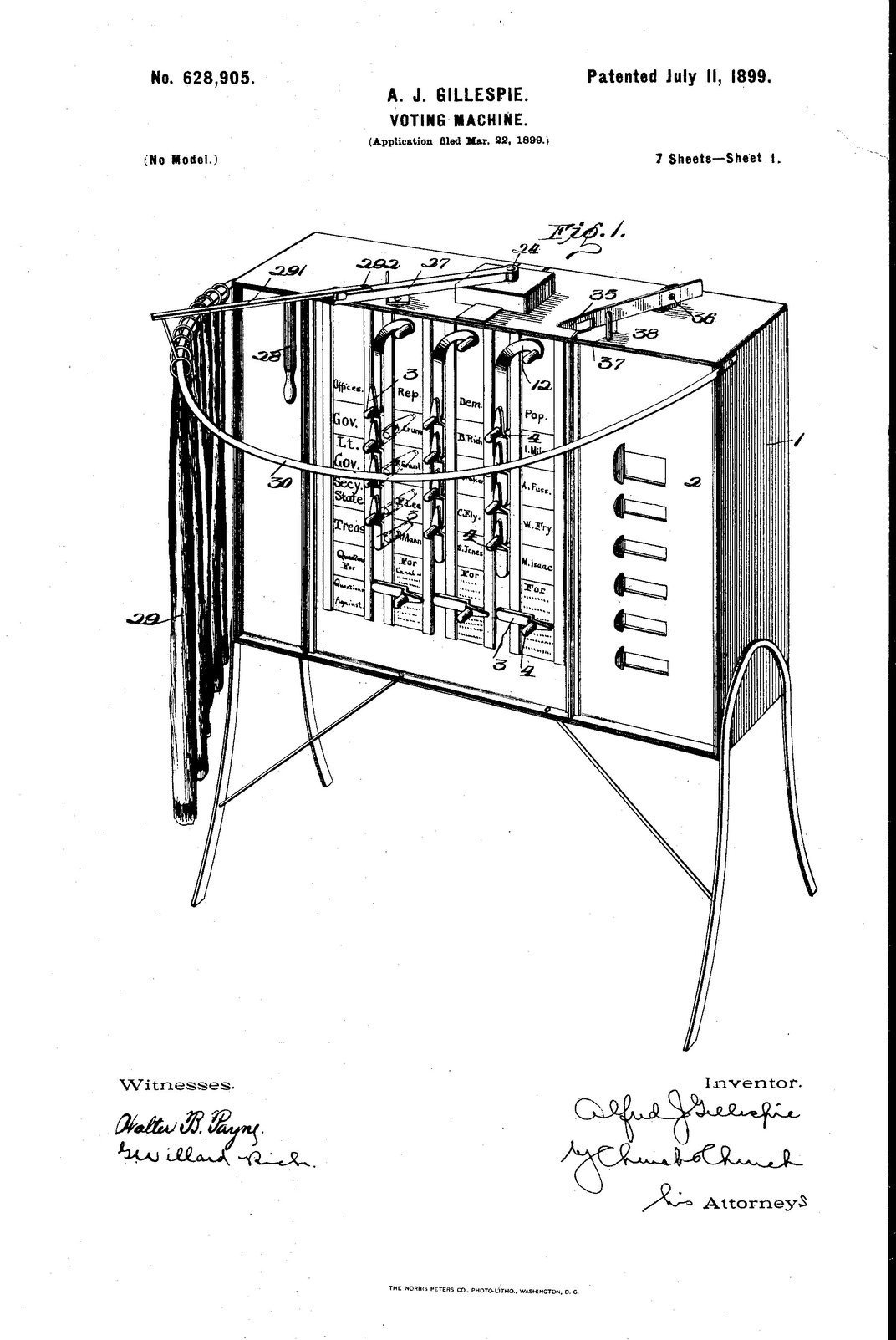

Lever voting machines have been around a long time.

Here’s a physical example:

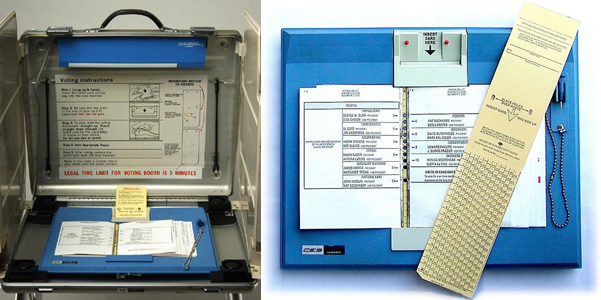

Punch card systems were developed in the 1960s and were last used in two Idaho counties in 2014, on the Votomatic provided by ES&S.

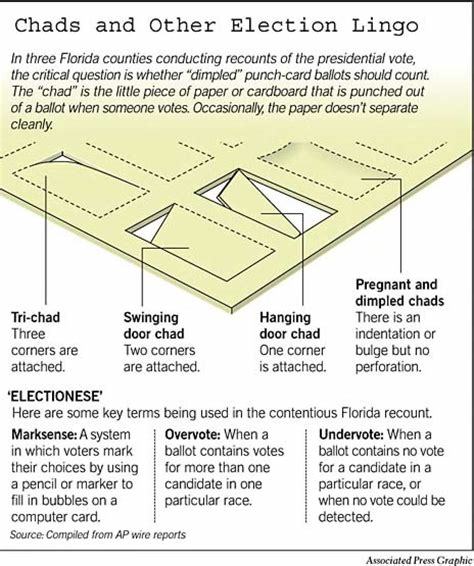

Fast forward to the 2000 presidential election between Al Gore and George W. Bush. Hanging chads on Sequoia Voting Systems punch-card voting system led to a recount, which Bush won.

Sequoia Voting Systems got its start in the 1970s as Mathematical Systems Corporation of Anaheim, California, offering an alternative to ES&S’s Votomatic punch cards. On March 8, 2005 Smartmatic Corp. (a Venezuelan company) acquired Sequoia. This raised eyebrows since Smartmatic had only the previous year been selected to by the Chavez-era Venezuelan government to provide voting systems for the presidential recall election, its first time providing machines for an election. Since June 4, 2010, Smartmatic’s parent company has been Dominion Voting Systems.

Dan Sundin summarizes Smartmatic well:

“Smartmatic was founded in 1998 by three Venezuelans, Antonio Mugica, Alberto Anzola, and Roger Pinate. Initially they developed ATMs in Mexico, but the U.S. presidential election in 2000 led the group to consider electronic voting platforms. Venezuelan strongman Hugo Chavez’s government gave the company an early loan and its first contract for election machines in 2004. The following year, Smartmatic bought Sequoia Voting Systes, but after a U.S. Department of Justice inquiry, Smartmatic sold Sequoia in 2007. More recently, Smartmatic has become a political lighting rod in the Philippines, with some politicians accusing the company of marketing faulty equipment and orchestrating election fraud.”

Back to 2000. According to Sequoia’s own employees, Sequoia may have been responsible for the defective punch cards in Florida which led to “hanging chads” or undervotes to the tune of 10,000 in Palm Beach County.

One of Sequoia’s workers told Dan Rather:

“My own personal opinion was the touch screen voting system wasn’t getting off the ground like that they—like they would hope. And because they weren’t having any problems with paper ballots. So, I feel like they—deliberately did all this to have problems with the paper ballots so the electronically voting systems would get off the ground—and which it did in a big way.”

Specifically, USC 52 Ch. 209 Subchapter I—PAYMENTS TO STATES FOR ELECTION ADMINISTRATION IMPROVEMENTS AND REPLACEMENT OF PUNCH CARD AND LEVER VOTING MACHINES. §20902 states: Replacement of punch card or lever voting machines.

Sequoia benefitted from the passage of federal legislation in 2002—the Help America Vote Act of 2002—because they manufactured electronic voting equipment.

In 2003 Beverly Harris found Diebold’s source code on the internet. Diebold had only entered the elections business a year prior through its purchase of Global Elections Systems, a touch-screen voting technology producer in Texas. The source code revealed that Diebold voting systems used an unsecured access database, meaning anyone could access, change data, and erase logs.

In 2007 Diebold Election Systems rebranded as Premier Election Solutions and in 2009 they sold to Election Systems & Software (ES&S), which by 2014 was the largest manufacturer of United States voting machines (and still used in the majority of Minnesota counties).

The Source Code Review of the Diebold Voting System was published by 6 authors on July 20, 2007, showed the system was 1) vulnerable to malicious software, 2) susceptible to viruses, 3) failed to protect ballot secrecy, and 4) vulnerable to malicious insiders.

More recently, one of the authors of the Diebold review, J. Alex Halderman of Princeton University, provided the Halderman Declaration on Georgia’s ballot marking devices (BMD). Halderman has also issued a sealed 25,000-word report on voting systems vulnerabilities.

In an emergency meeting in Otero County, New Mexico in May 2022, nation-state vulnerability expert Jeff Lensberg provided further vulnerabilities, some of which he’d uncovered previously in the Antrim County, Michigan investigation. Of particular concern was his vote switching demonstration.

Putting the History in Context

The history of voting machines spans over 100 years. However the use of electronic voting machines is very short, only two to three decades. During almost the entirety of that duration, the electronic systems have been shown to be insecure, hackable, and manipulable, sometimes if not often by design.

If access can be gained, whether remotely, over a network, or through the internet, and once inside the machines or databases are configured to be manipulable, then there is ample room for subversion. Even if internet connectivity could be proven not to occur (it has been shown to have occurred), should citizens trust machines that have disturbing baked-in features?

The lack of certifications (and the uselessness of certifications) of voting machines is further troubling.

In the Tarrant County, TX, in the first half of 2022, Col. Shawn Smith describes why:

“…And for the people who said well, the machines are certified, I would say, the space shuttle Columbia was also certified for flight. How’d that turn out? The Boeing 737 Max was certified for passenger operations, and then crashed killing over 500 people in two separate accidents before they finally let experts take a look at it. And my point in saying that is not to try to scare people, but just to say that based on my experience, and I’m not a cyber professional, but I work with cyber pros, and I know the difference between somebody who knows cyber and somebody who doesn’t. And if you don’t know the difference, then you’re in very dangerous territory when you try to make any conclusions or try to listen to someone who doesn’t really know what they’re talking about.

“Our voting systems from my perspective based on the expert examiner’s report, cannot be trusted with our election. And what they require in order to for you to verify for yourself is that you become a cyber expert. Otherwise, you’re forced to trust other people who say they’re experts, people who have conflicts of interest, and people who’ve been trained essentially by the National Association of Secretaries of State, the election directors, and the Election Assistance Commission…”

Certifications Are Less Than Useless

Clay Parikh was an expert witness in the 2024 Georgia hearings where he demonstrated how to subvert the database of an election system, one of a couple thousand ways to skin the cat, as he said on record. Parikh worked at one of the EAC’s testing labs for about 9 years and told David Clements in an extended interview for the documentary, Let My People Go, that the security of the elections systems was 0.5 out of 10, because he couldn’t with honesty give them a 1.

Throughout its certification process, the Election Assistance Commission (EAC) which was established by the Help America Vote Act (2002) has not certified about 95% of Minnesota counties.

Those county’s electronic voting equipment are merely certified by the Minnesota Secretary of State, even though similar testing labs are used. The few counties that are EAC certified have the problem indicated by Col. Shawn Smith, that those certifications provide the illusion of security when in fact those systems are anything but ready to run secure elections, and by the EAC certificate’s own language not an endorsement of the products.

(The same illusion exists with Minnesota being a ‘paper ballot’ state. We have paper ballots, but do we count paper ballots? By default, No. Indeed, the tabulators take a picture through their scanning technology, and then these computers read the digital image, also known as a ballot image, to document the voter’s oval selections. However, audits of these selections are never done as part of the normal post-election review process, a serious gap in the public’s knowledge and ability to provide oversight on the MNSOS’s reported results.)

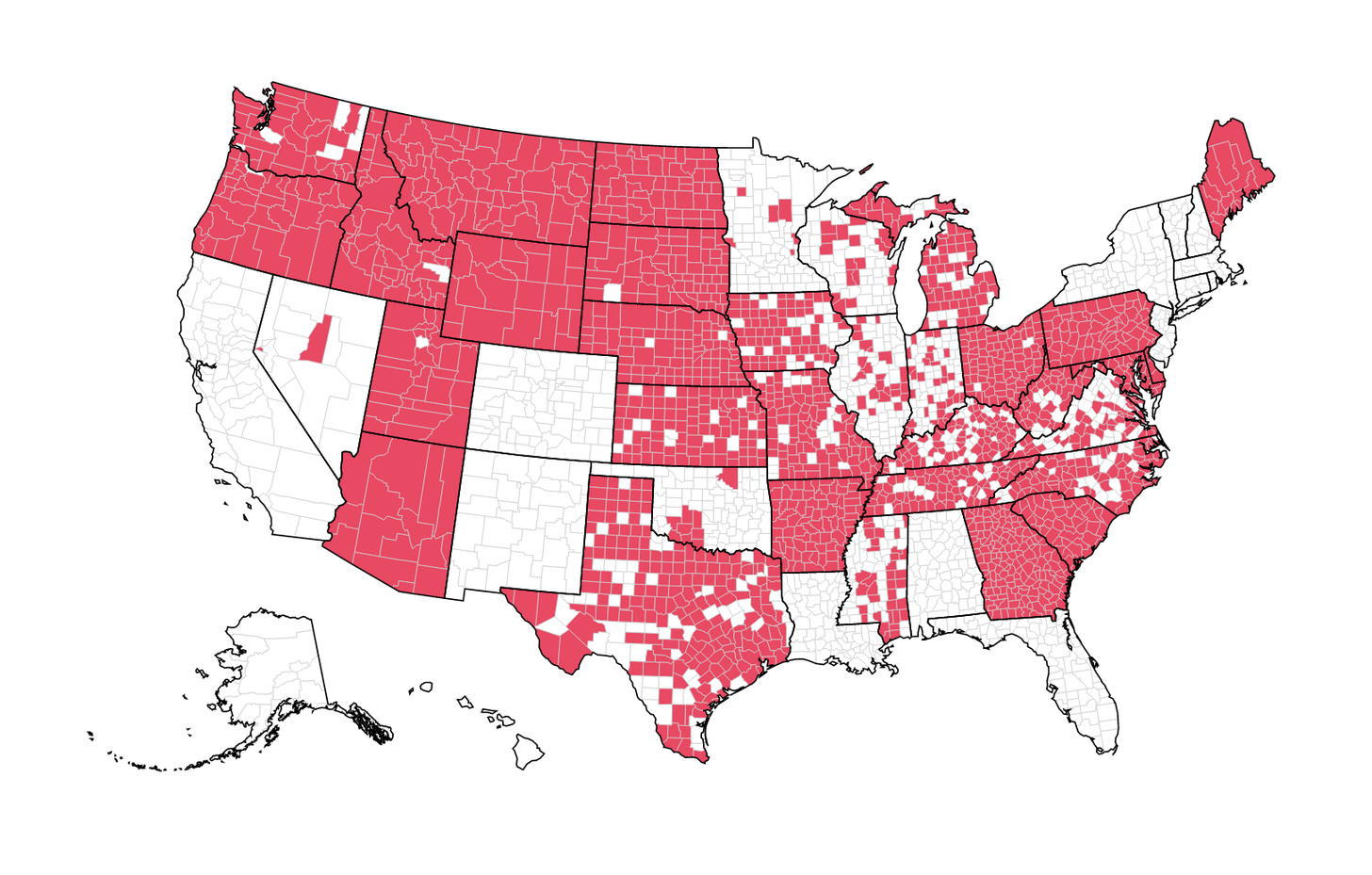

Back to certifications… Let’s take a look at the certification maps. Remember, being certified or not certified doesn’t guarantee system security, as we shall discuss shortly.

In the following image, Red = Certified | White = Not Certified

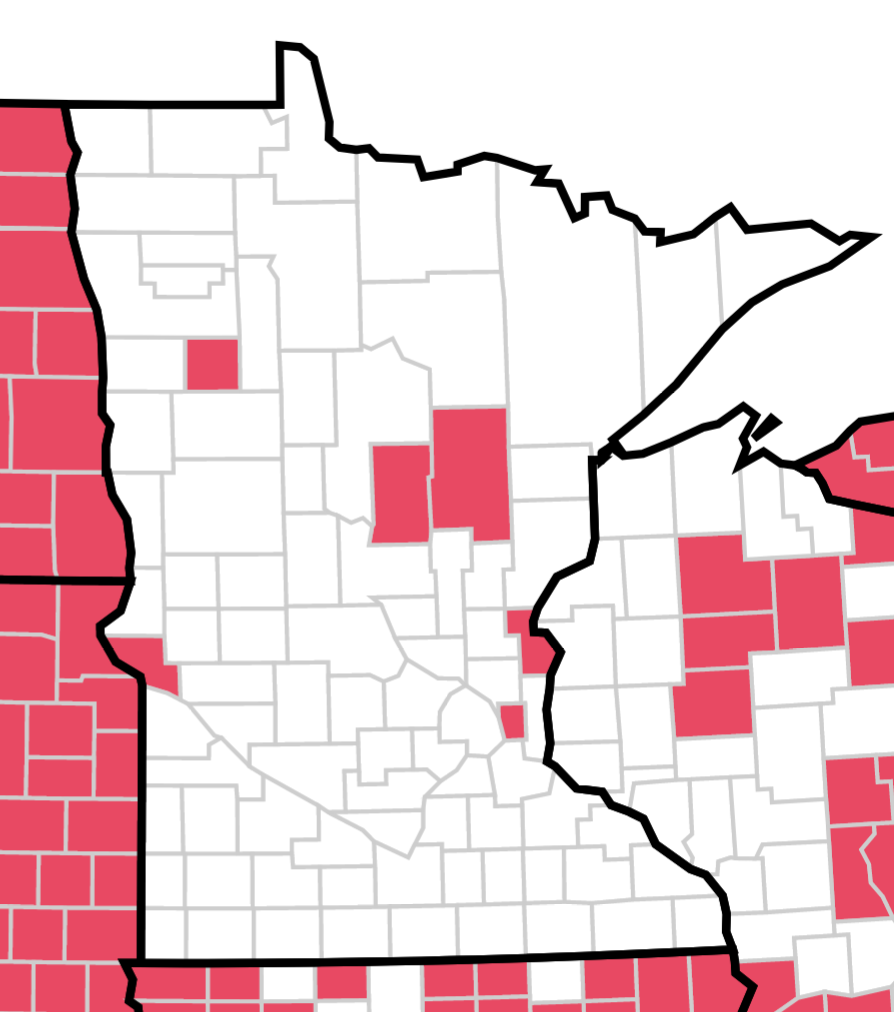

If we zoom in on Minnesota, we find that only 6 of 87 counties have voting equipment that is certified by the EAC. Remember, red counties are certified, white are not certified.

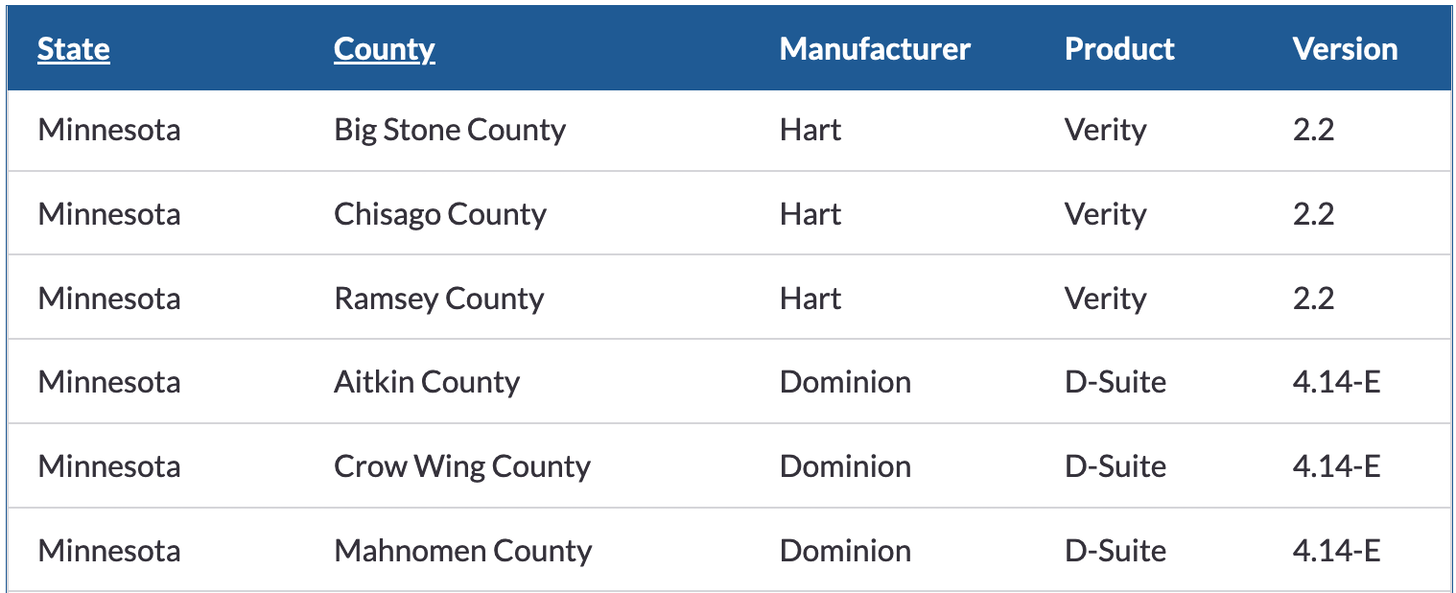

Here are the counties in Minnesota that were certified by the EAC as of April 2022:

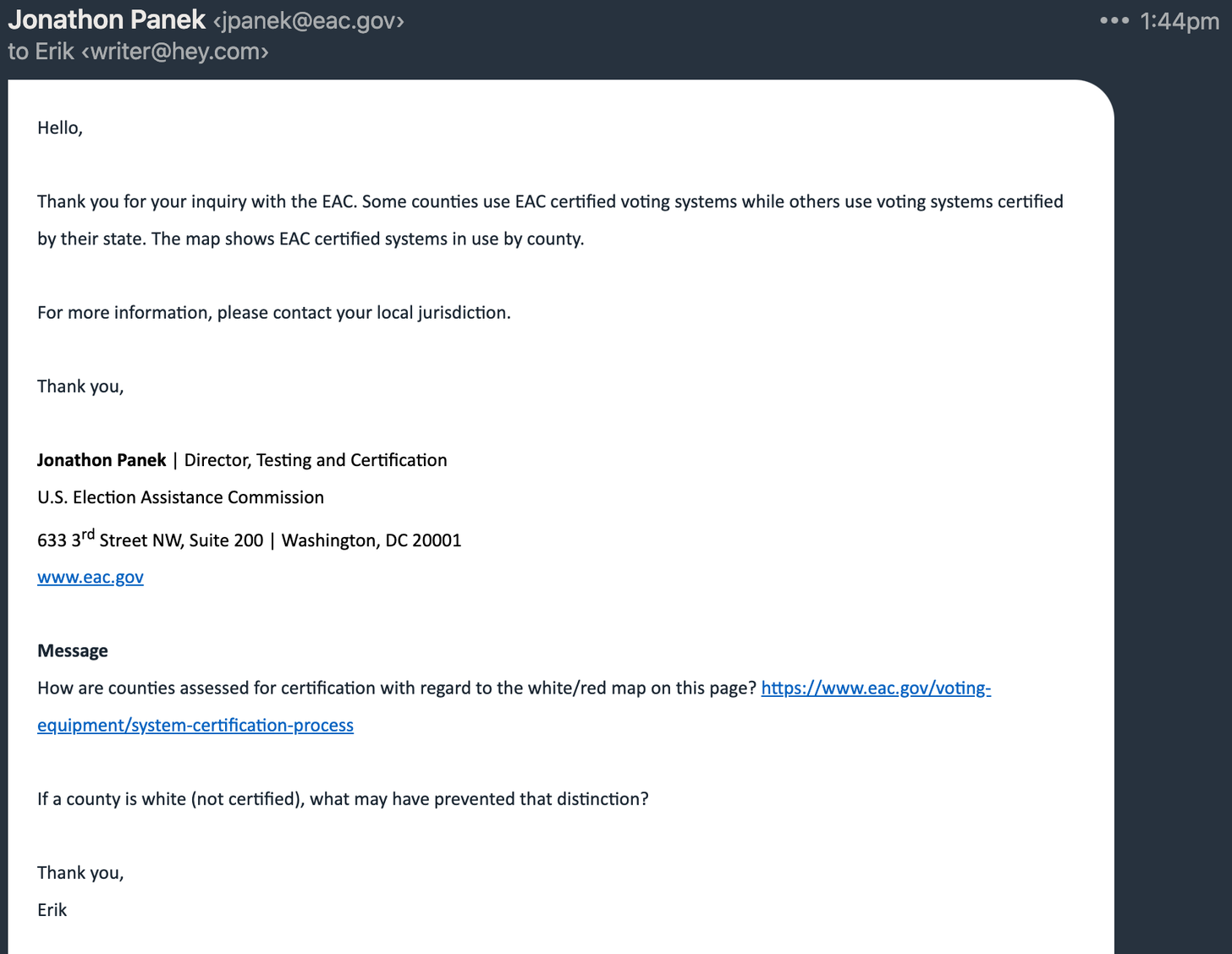

Thinking that this felt off, I called the EAC and left a voicemail and sent a question by email, which was replied to the same day (04/20/2022).

This may have been comforting if not for a close reading of Minnesota election law.

Minnesota Statute 206.57, Subd.6 states in full:

Subd. 6.Required certification.

In addition to the requirements in subdivision 1, a voting system must be certified by an independent testing authority accredited by the Election Assistance Commission or appropriate federal agency responsible for testing and certification of compliance with the federal voting systems guidelines at the time of submission of the application required by subdivision 1 to be in conformity with voluntary voting system guidelines issued by the Election Assistance Commission or other previously referenced agency. The application must be accompanied by the certification report of the voting systems test laboratory. A certification under this section from an independent testing authority accredited by the Election Assistance Commission or other previously referenced agency meets the requirement of Minnesota Rules, part 8220.0350, item L. A vendor must provide a copy of the source code for the voting system to the secretary of state. A chair of a major political party or the secretary of state may select, in consultation with the vendor, an independent third-party evaluator to examine the source code to ensure that it functions as represented by the vendor and that the code is free from defects. A major political party that elects to have the source code examined must pay for the examination. Except as provided by this subdivision, a source code that is trade secret information must be treated as nonpublic information, according to section 13.37. A third-party evaluator must not disclose the source code to anyone else.

It is important to note that as of now there are no other appropriate federal agencies outside of the Election Assistance Commission (EAC), which itself authorizes Pro V&V and SLI Compliance.

Bonus: As a reminder, check out the documentary film Let My People Go, free online, where Professor David Clements interviews Clay Parikh, who worked in the testing labs, where he describes the certifications as providing 0.5 out of 10 because he couldn’t honestly give them 1 out of 10.

Are There Limits to Certifications from the EAC?

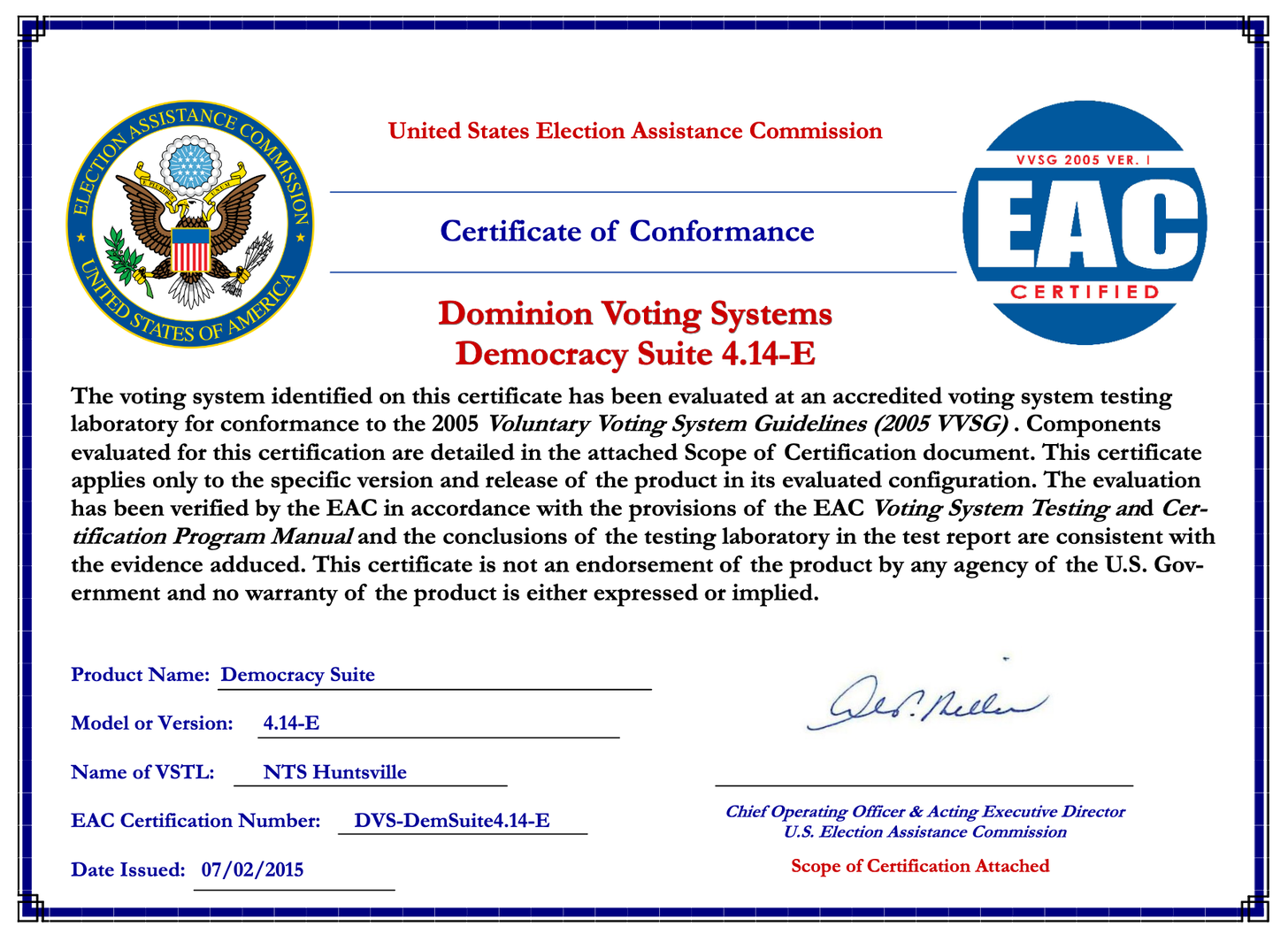

Let’s take a look at the EAC certification for Dominion 4.14-E.

On page 1 note the last sentence:

“This certificate is not an endorsement of the product by any agency of the U.S. Government and no warranty of the product is either expressed or implied.”

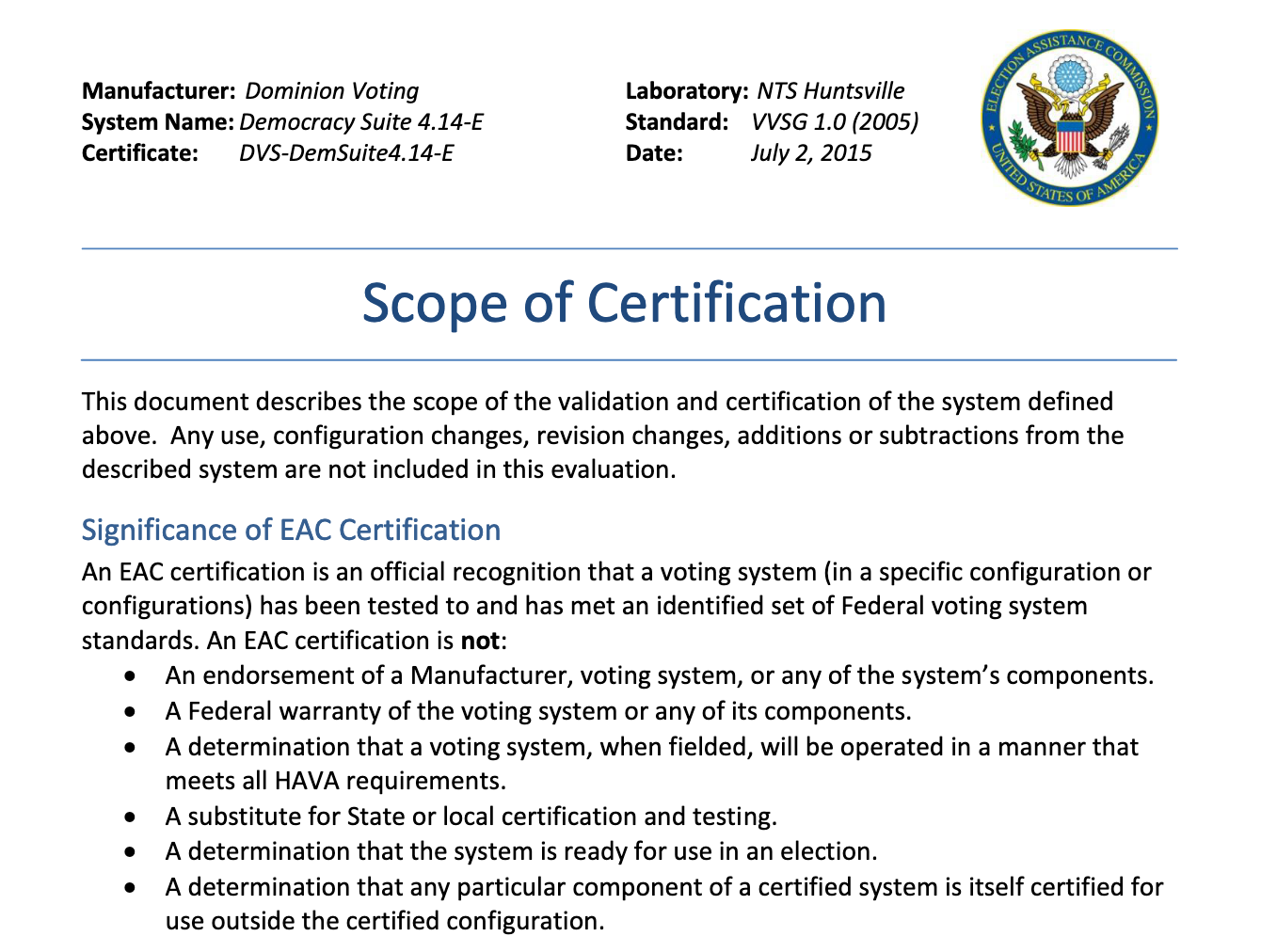

On page 2 it reads:

Note the second to last bullet point in “Significance of EAC Certification”:

“An EAC certification is not: A determination that the system is ready for use in an election.”

Then what might these certifications be for?

Are they meant to give the public a false sense of security?

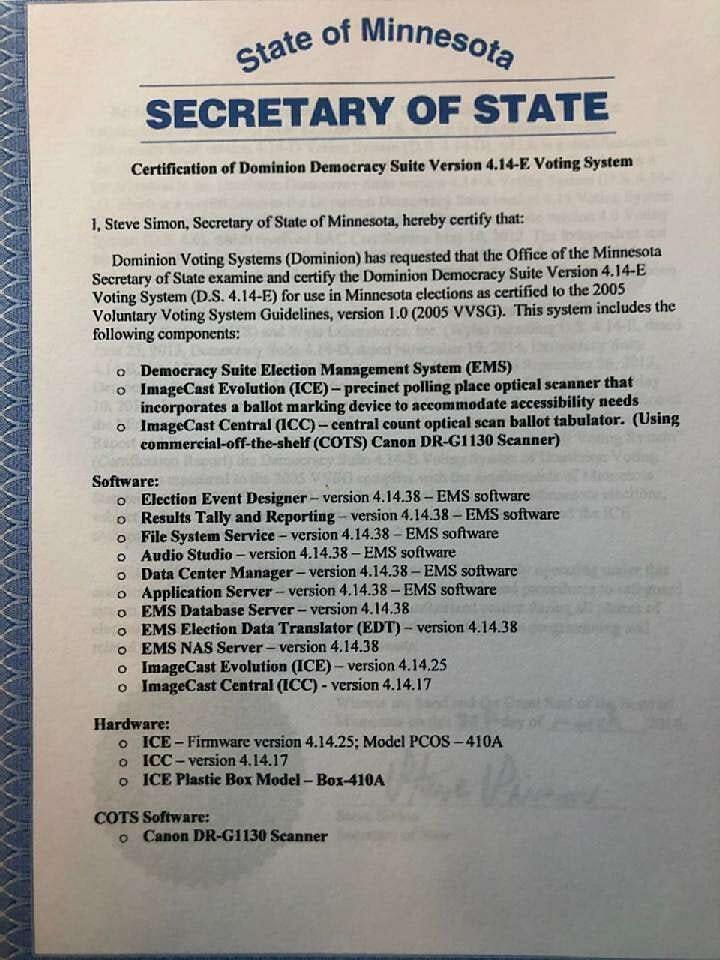

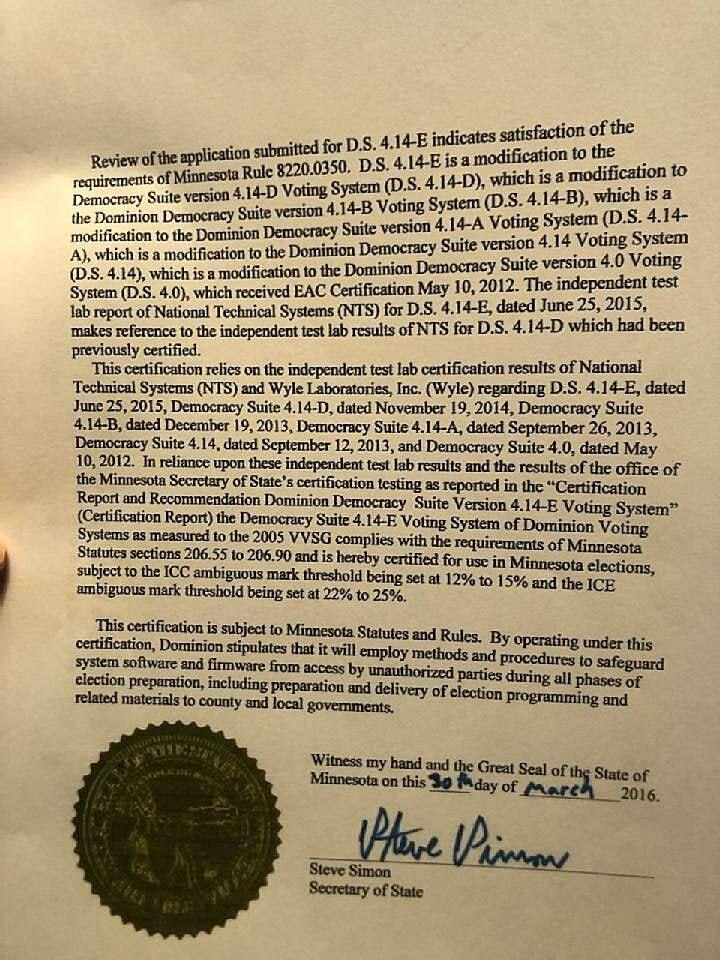

Finally, compare the full 14-page EAC certification to the State of Minnesota Secretary of State Certification of Dominion Democracy Suite Version 4.14-E Voting System reproduced below:

And page 2 of the same:

What did you notice?

It reads very similarly, sometimes verbatim, to the EAC’s certifications, which the EAC admits do not indicate a voting machine is ready for use in an election. If the secretary of state is using much of the EAC’s language to describe the certification, and the EAC certificates themselves say they are not a determination of whether a system is ready for use in an election, how then did the secretary of state deem them ready for use?

Should the public have questions when 81 out of 87 counties in Minnesota DO NOT have certified election equipment according to the Election Assistance Commission, which under Minnesota Statute 206.57 Subd.6 those election machines should have prior to use?

Are there consequences to certifications (the EAC certifications) which have disclaimers putting the value of the certification itself into question? Should we be concerned when our secretary of state basically copy-pasted the EAC’s certificate language into his own machine certifications?

Mail In Voting

No-excuse mail-in began was passed into law in 2014 and went into effect in 2015 leading to large increase in absentee/mail-in ballots and votes. Steve Simon, at the end of his 10 years from 2005-2015 as a House Representative for District 46B, sat on the Legislature’s Election Committee, where the No-excuse mail-in was proposed and drafted. He would have additional influence into the early and mid-2020s as well, in particular legislatively with the Voting Rights Act of 2023 and locally with providing specific guidance to prevent information spreading about the true nature of the electronic poll pads, from KNOWiNK, first introduced in 2016 in Hennepin County.

- A 1987 law made it possible for precincts to switch to mail-in only

- In 2016 the thresholds from 1987 were lowered; outside metro precincts with fewer than 1,000 registered voters, metro areas with fewer than 400, could opt for mail-in only

- There are currently 1,000+ precincts (out of 4,000 statewide) whose voters may only vote by mail (mail ballots can be hand-delivered, but no in-precinct election day voting allowed)

When mail-in voting is outlawed federally it will go a long way to setting the tone for serious legislative reforms toward free, honest, and fair elections with warranted trustworthiness.

If we continue the status quo where such a large proportion of ballots (and votes) come through a process that lacks basic chain of custody, then who is to say how many of the ballots are indeed legitimate or not?

Electronic Poll Pads

Why are the MNSOS, multiple attorneys, and county level auditors and election managers so desperate to have these iPads, while answering very few tough questions about the software embedded in them?

In late 2024 I was put on hold for about five minutes at the Office of the Secretary of State (OSS) for asking a simple question about electronic poll pads, only to be transferred to someone who then deferred me to yet another person who did not answer the phone and did not call me back.

My recent look into Hennepin County’s KNOWiNK contracts stalled when it was relayed to me that the “No responsive data” was returned because the Hennepin County Attorney was included on the emails I’d requested between KNOWiNK, OSS, and Hennepin County, allowing attorney-client privilege to block public access.

I do not know anyone who has reviewed the KNOWiNK source code, nor am I likely to find somebody who has, given that KNOWiNK is a non-governmental organization (NGO), a 3rd-party, private vendor. Despite the integral nature of their hardware and software to local, state, and nationwide elections, and despite the fact that KNOWiNK’s iPads are either wi-fi connected or cellular connected (still internet), and are therefore vulnerable to remote access, the Elections Assistance Commission is not required to certify the equipment or software in order for it to be fit for elections in Minnesota—the Minnesota Secretary of State determines that.

My suspicion of electronics, computers, and many things digital dates from my days working for a Fortune 50 in Minneapolis. I had landed in this particular area of the company by mentioning to the hiring manager the development of an iOS app (for iPhone and iPad) that a small team and I designed and implemented in 2013. My job was primarily as a liaison between several business departments and the IT department, at the time when the company experienced a well-publicized data and security breach where hackers gained remote access to Target’s servers: the hackers exploited first the HVAC system and then slipped executable files through a web portal which granted them remote access, eventually compromising data of 70 million customers, including 40 million credit cards.

The Cost of Secrecy

I am not the only one suspicious of these KNOWiNK devices.

Minnesota’s first rollout of the KNOWiNK electronic poll pads occurred in Hennepin County in 2016, where the Mayor of St. Bonifacius, during the product presentation, within mere minutes hacked the system and didn’t like the contract (which said if harmful code was embedded, then the county would not be liable), and his council voted not to use the iPads, leading to him being threatened with a lawsuit (which did not deter the council); St. Bonifacius became the only municipality of more than 40 in Hennepin, Minnesota’s largest county by population to use pen and paper to check in voters on election day.

By 2018, much of Minnesota quietly received the KNOWiNK iPads and embedded software, except for those areas with poor internet service.

The bigger question, though, might be less related to the fact of internet connection than what exactly such a connection might enable, even if the hardware or software worked as designed on election day without any security breaches.

On this path of thinking, it is to be noted that the widespread readiness of these electronic poll pads was just in time for a significant 2018 midterms and the nationwide presidential election two years later. In 2020, the availability of the electronic poll pads coincided with, in Minnesota, the unconstitutional route taken through LaRose v. Simon and NAACP v. Simon (Simon fully participating) to waive absentee mail-in vote witness signature requirements AND extend the acceptance deadline.

At 3:57pm on election day, 2020, the Minnesota Attorney General tweeted that ‘we don’t have all the votes we need quite yet’ and went on to recommend people get their friends go vote. It is conceivable that, combined with the already-collected absentee voting data from the 46-day absentee period, that the real-time access on election day itself—through the electronic poll pads acting as eyes and ears—provided Ellison information prompting him to post a tweet, which in turn may have activated certain levers such as additional absentee ballot dropoffs to later be reconciled with voters who had not voted, although this reconciliation took considerable time…

The biggest fact about Minnesota elections from 2020, that never became a headline, from any outlets, was that there were 700,000 MORE votes than voters on November 29, 2020, according the Statewide Voter Registration System (SVRS), which is managed by the Minnesota Secretary of State Steve Simon, five days after he and the other four members of the MN State Canvassing Board looked past this glaring fact to certify the election anyway. I myself did not learn this until attending a presentation first from Rick Weible (in 2021) and then from him and Susan Shogren Smith (in February 2022), in my mind the ONLY attorney in Minnesota to truly and fully stand with the people demanding transparency in government-administrated elections as documented by the petition to stop the 2020 certification on account of the missing voters and other irregularities, which was never heard by the Minnesota Supreme Court based on their dismissing it using a lame procedural tactic.

Reviving Suppressed Technology: Pen and Paper

The lack of transparency, including deliberate obfuscation in certain cases, are instances of irregularities that arouse yet further doubt in the officially stated purpose for having these devices, which is merely primarily to check in voters.

In a January 22, 2025 letter to cities considering e-poll pads, Rick Weible, the mayor who successfully defended his city’s voters from the initial release of KNOWiNK in 2016, wrote: “You should know what you are signing up for, remember paper poll books cannot be hacked remotely since they for sure cannot be connected to a Wi-Fi, internet, or any network.”

More recently, two (2) cities in Anoka County, Oak Grove and Ramsey, have cancelled their contracts, and now election managers, county attorneys, and the MNSOS are arguing that those cities are somehow still required to use them, seemingly ignoring Minn Stat §201.225 which refers to authorization in subdivision 1 and the revoking of usage in subdivision 6. If there is no choice for cities (or indeed counties), then the 95th Minnesota Legislature should clarify, just as the 93th Minnesota Legislature clarified unconstitutionally to require the usage of electronic tabulators for those precincts that previously used them (unconstitutional by ex-post facto). (Then, in 2024, the 94th Minnesota Legislature made it extremely difficult to hand count by inserting language that ballots must be sealed immediately after the close of polls.)

Anoka County commissioners are considering buying yet another batch of iPads from KNOWiNK on February 25, 2025, despite many good reasons NOT to (video: Ramsey), while other counties that don’t yet use them, like Isanti, are also being offered the hardware and software.

One wonders whether paper and pen are being equally considered.