Network Programming Techniques for the Internet of Things

This chapter will show you techniques of network programming relevant to developing Internet of Things (IoT) projects and products using local TCP/IP and UDP networking. We will not cover the design of hardware or designing IoT user experiences. Specifically, we will look at techniques for using local directory services to publish and look up available services and techniques for efficiently communicating using UDP, multicast and broadcast.

This chapter is a tutorial on network programming techniques that I believe you will find useful for developing IoT applications. The material on User Data Protocol (UDP) and multicast is also useful for network game development.

I am not covering some important material: the design of user experience and devices, and IoT devices that use local low power radios to connect cooperating devices. That said, it is worth thinking about what motivates the development of IoT devices and we will do this in the next section.

There are emerging standards for communication between IoT devices and open source projects like TinyOS and Contiki that are C language based, not Java based, so I won’t discuss them. Oracle supports the Java ME Embedded profile that is used in some IoT products but in this chapter I want to concentrate network programming techniques and example programs that run on stock Java (including Android devices).

Motivation for IoT

We are used to the physical constraints of using computing devices. When I was in high school in the mid 1960s and took a programming class at a local college I had to make a pilgrimage to the computer center, wait for my turn to use a keypunch machine, walk over to submit my punch cards, and stand around and wait and eventually get a printout and my punch cards returned to me. Later, interactive terminals allowed me to work in a more comfortable physical environment. Jumping ahead almost fifty years I can now use my smartphone to SSH into my servers, watch movies, and even use a Java IDE. As I write this book, perhaps 70% of Internet use is done on mobile devices.

IoT devices complete this process of integrating computing devices more into our life with fewer physical constraints on us. Our future will include clothing, small personal items like pens, cars, furniture, etc., all linked in a private and secure data fabric. Unless you are creating content (e.g., writing software, editing pictures and video, or performing a knowledge engineering task) it is likely that you won’t think too much about the devices that you interact with and in general will prefer mobile devices. This is a similar experience to driving a car where tasks like braking, steering, etc. are “automatic” and don’t require much conscious thought.

We are physical creatures. Many of us gesture with our hands while talking, move things around on our desk while we are thinking, and generally use our physical environment. Amazing products will combine physical objects and computing and information management.

Before diving into techniques for communication between IoT devices, we will digress briefly in the next section to see how to run the sample programs for this chapter.

Running the example programs

If you want to try running the example programs let’s set that up before going through the network programming techniques and code later in this chapter. Assuming that you have cloned the github repository for the examples in this book, go to the subdirectory internet_of_things, open two shell windows and use the following commands to run the examples in the same order that they are presented (these commands are in the README.md file so you can copy and paste them). These commands have been split to multiple lines to fit the page width of this book:

Build

1 mvn clean compile package assembly:single

Run service discovery

1 java -cp target/iot-1.0-SNAPSHOT-jar-with-dependencies.jar \

2 com.markwatson.iot.CreateTestService

3 java -cp target/iot-1.0-SNAPSHOT-jar-with-dependencies.jar /

4 com.markwatson.iot.LookForTestService

Run UDP experiments:

1 java -cp target/iot-1.0-SNAPSHOT-jar-with-dependencies.jar \

2 com.markwatson.iot.UDPServer

3 java -cp target/iot-1.0-SNAPSHOT-jar-with-dependencies.jar \

4 com.markwatson.iot.UDPClient

5

6 # Multicast experiments:

7 java -cp target/iot-1.0-SNAPSHOT-jar-with-dependencies.jar \

8 com.markwatson.iot.MulticastServer

9 java -cp target/iot-1.0-SNAPSHOT-jar-with-dependencies.jar \

10 com.markwatson.iot.MulticastClient

Line 2 compiles and builds the examples. For each of the example programs you will run two programs on the command line. For example for the service discovery example on lines 5 and 6 (which would be entered on one line in a terminal window) we start a test service and lines 7 and 8 run the service test client. Similarly, lines 10 through 20 show how to run the services and test clients for the UDP experiments and the multicast experiments. I repeat these instructions with each example as we look at the code but I thought that you might enjoy running all three examples before we look at the implementations of the examples later in this chapter.

In each example, run the two example programs in different shell windows. For more fun, run the examples using different laptops or any device that can run Java code.

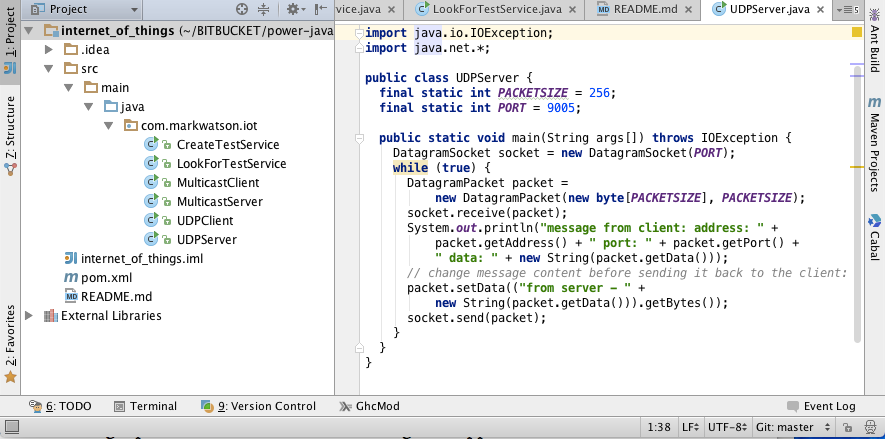

The following figure shows the project for this chapter in the Community Edition of IntelliJ:

This chapter starts with a design pattern that you might use for writing IoT applications. Then the following three major sections show you how to use directory lookups, use User Data Protocol (UDP) instead of TCP/IP, and then multi-cast/broadcast.

The material in this chapter is fairly elementary but it seems like many developers don’t have experience with lower level network programming techniques. My hope is that you will understand when you might want to use a lower level protocol like UDP instead of TCP and when you might find directory lookups useful in your applcations.

Design Pattern

The pattern that the examples in the following sections support is simple (in principle): small devices register services that they offer and look for services offered in other devices. Devices will use User Data Protocol (UDP) and multi-cast to communicate for using and providing services. Once a consumer has discovered a service privider (host, IP address, port, and service types) a consumer can also open a direct TCP/IP socket connection to a provider to use a newly discovered service.

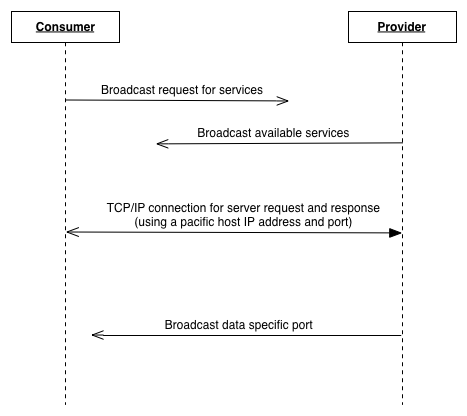

The following diagram shows several IoT use cases:

- A consumer uses the JmDNS library to broadcast on the local network a request for services provided.

- The JmDNS library on the provider side hears a service description request and broadcasts available services.

- The JmDNS library on the consumer side listens for the broadcast from the provider.

- Using a service description, the consumer makes a direct socket connection to the provider for a service.

- The provider periodically broadcasts updated data for its service.

- The consumer listens for broadcasts of updated data and uses new data as it is available.

This figure shows a few use cases. You can use these interaction patterns of interactions between IoT devices using application specific software you write.

Directory Lookups

In the next two sub-sections we will be using the Java JmDNS library that supports a local multi-cast Domain Name Service (DNS) and supports service discovery. JmDNS is compatible with Apple’s Bonjour discovery service that is also available for installation on Microsoft Windows.

JmDNS has been successfully used in Android apps if you change the defaults on your phone to accept multi-cast (since Android version 4.1 Network Service Discovery (NDS)). Android development is outside the scope of this chapter and I refer you to the NDS documentation and example programs if you are interested. I tried the example Android NsdChat application on my Galaxy S III (Android 4.4.2) and Note 4 (Android 5.0.1) and this example app would be a good place for you to start if you are interested in using Android apps to experiment with IoT development.

Create and Register a Service

The example program in this section registers a service using the JmsDNS Java library that listens on port 1234. In the next section we look at another example program that connects to this service.

1 package com.markwatson.iot;

2

3 import javax.jmdns.*;

4 import java.io.IOException;

5

6 public class CreateTestService {

7 static public void main(String[] args) throws IOException {

8 JmDNS jmdns = JmDNS.create();

9 jmdns.registerService(

10 ServiceInfo.create("_http._tcp.local.", "FOO123.", 1234,

11 0, 0, "any data for FOO123")

12 );

13 // listener for service FOO123:

14 jmdns.addServiceListener("_http._tcp.local.", new Foo123Listener());

15 }

16

17 static class Foo123Listener implements ServiceListener {

18

19 public void serviceAdded(ServiceEvent serviceEvent) {

20 System.out.println("FOO123 SERVICE ADDED in class CreateTestService");

21 }

22

23 public void serviceRemoved(ServiceEvent serviceEvent) {

24 System.out.println("FOO123 SERVICE REMOVED in class CreateTestService");

25 }

26

27 public void serviceResolved(ServiceEvent serviceEvent) {

28 System.out.println("FOO123 SERVICE RESOLVED in class CreateTestService");

29 }

30 }

31 }

The service is created in lines 10 and 11 defining the service name (notice that a period is added to the end of the service name FOO123), the port that the server listens on (1234 in this case), and the last argument is any string data that you also want to pass to clients looking up information on service FOO123. When you run the client in the next section you will see that the client receives this information for the local DNS lookup.

Running this example produces the following output (edited to fit the page width):

Lookup a Service by Name

If you have the service created by the example program in the last section running then the following example program will lookup the service.

1 package com.markwatson.iot;

2

3 import javax.jmdns.*;

4 import java.io.IOException;

5

6 // reference: https://github.com/openhab/jmdns

7

8 public class LookForTestService {

9

10 static public void main(String[] args) throws IOException {

11 System.out.println("APPLICATION entered registerService");

12 JmDNS jmdns = JmDNS.create();

13 // try to find a service named "FOO123":

14 ServiceInfo si = jmdns.getServiceInfo("_http._tcp.local.", "FOO123");

15 System.out.println("APPLICATION si: " + si);

16 System.out.println("APPLICATION APP: " + si.getApplication());

17 System.out.println("APPLICATION DOMAIN: " + si.getDomain());

18 System.out.println("APPLICATION NAME: " + si.getName());

19 System.out.println("APPLICATION PORT: " + si.getPort());

20 System.out.println("APPLICATION getQualifiedName: " + si.getQualifiedName());

21 System.out.println("APPLICATION getNiceTextString: " + si.getNiceTextString(\

22 ));

23 }

24 }

We use the JmsDNS library in lines 12 and 14 to find a service by name. In line 14 the first argument “_http._tcp.local.” indicates that we are searching the local network (for example, your home network created by a router from your local ISP).

Running this example produces the following output (edited to fit the page width):

> java -cp target/iot-1.0-SNAPSHOT-jar-with-dependencies.jar \

com.markwatson.iot.LookForTestService

APPLICATION entered registerService

APPLICATION si: [ServiceInfoImpl@1595428806

name: 'FOO123._http._tcp.local.' address: '/192.168.0.14:1234'

status: 'DNS: Marks-MacBook-Air-local.local.

state: probing 1 task: null', has data empty]

APPLICATION APP: http

APPLICATION DOMAIN: local

APPLICATION NAME: FOO123

APPLICATION PORT: 1234

APPLICATION getQualifiedName: FOO123._http._tcp.local.

APPLICATION getNiceTextString: any data for FOO123

Do you want to find all local services? Then you can also create a listener that will notify you of all local HTTP services. There is an example program in the JmsDNS distribution on the path src/sample/java/samples/DiscoverServices.java written by Werner Randelshofer. I changed the package name to com.markwatson.iot and added it to the git repository for this book. You can try it using the following commands:

While it is often useful to find all local services, I expect that for your own projects you will be writing both service and client applications that cooperate on your local network. In this case you know the service names and can simply look them up as in the example in this section.

User Data Protocol Network Programming

You are most likely familiar with using TPC/IP in network programming. TCP/IP provides some guarantees that the sender is notified on failure to deliver data to a receiving program. User Data Protocol (UDP) makes no such guarantees for notification of message delivery and is very much more efficient than TCP/IP. On local area networks data delivery is more robust to failure compared to the Internet and since we are programming for devices on a local network it makes some sense to use a lower level and more efficient protocol.

Example UDP Server

The example program in this section implements a simple service that listens on port 9005 for UDP packets that are client requests. The UDP packets received from clients are assumed to be text and this example slightly modifies the text and returns it to the client.

1 package com.markwatson.iot;

2

3 import java.io.IOException;

4 import java.net.*;

5

6 public class UDPServer {

7 final static int PACKETSIZE = 256;

8 final static int PORT = 9005;

9

10 public static void main(String args[]) throws IOException {

11 DatagramSocket socket = new DatagramSocket(PORT);

12 while (true) {

13 DatagramPacket packet =

14 new DatagramPacket(new byte[PACKETSIZE], PACKETSIZE);

15 socket.receive(packet);

16 System.out.println("message from client: address: " + packet.getAddress() +

17 " port: " + packet.getPort() + " data: " +

18 new String(packet.getData()));

19 // change message content before sending it back to the client:

20 packet.setData(("from server - " + new String(packet.getData())).getBytes(\

21 ));

22 socket.send(packet);

23 }

24 }

25 }

In line 11 we create a new DatagramSocket listener on port 9005. On lines 13 and 14 we create a new empty DatagramPacket that is used in line 16 to hold data from a client. The example code prints out packet data, changes the text from the client, and returns the modified text to the client.

Running this example produces the following output (edited to fit the page width):

1 > java -cp target/iot-1.0-SNAPSHOT-jar-with-dependencies.jar \

2 com.markwatson.iot.UDPServer

3 message from client: address: /127.0.0.1 port: 63300

4 data: Hello Server1431540275433

Note that you must also run the example program from the next section to get the output in lines 4 and 5. This is why I listed the commands at the beginning of the chapter for running all of the examples: I thought that if you ran all of the examples according to these earlier directions, the example programs would be easier to understand.

Example UDP Client

The example program in this section implements a simple client for the UDP server in the last section. A sample text string is sent to the server and the response is printed.

1 package com.markwatson.iot;

2

3 import java.io.IOException;

4 import java.net.*;

5

6 public class UDPClient {

7

8 static String INET_ADDR = "localhost";

9 static int PORT = 9005;

10 static int PACKETSIZE = 256;

11

12 public static void main(String args[]) throws IOException {

13 InetAddress host = InetAddress.getByName(INET_ADDR);

14 DatagramSocket socket = new DatagramSocket();

15 byte[] data = ("Hello Server" + System.currentTimeMillis()).getBytes();

16 DatagramPacket packet = new DatagramPacket(data, data.length, host, PORT);

17 socket.send(packet);

18 socket.setSoTimeout(1000); // 1000 milliseconds

19 packet.setData(new byte[PACKETSIZE]);

20 socket.receive(packet);

21 System.out.println(new String(packet.getData()));

22 socket.close();

23 }

24 }

Running this example produces the following output (edited to fit the page width):

I have used UDP network programming in many projects and I will mention two of them here. In the 1980s I was an architect and developer on the NMRD project that used 38 seismic research stations around the world to collect data that we used to determine if any country was conducting nuclear explosive tests. We used a guaranteed messaging system for meta control data but used low level UDP for much of the raw data transfer. The other application was communcations library for networked racecar and hovercraft games that ran on a local network. UDP is very good for local network game development because it is efficient and the chance of losing data packets is very low and even if packets are lost game play is usually not affected. Remember that when using UDP you are not guaranteed delivery of data and not guaranteed notification of failure!

Multicast/Broadcast Network Programming

The examples in the next two sections are similar to the examples in the last two sections with one main difference: a server periodically broadcasts data using UDP. The server does not care if any client is listening or not, it simply broadcasts data. If any clients are listening they will probably receive the data. I say that they will probably receive the data because UDP provides no delivery guarantees.

There are specific INET addresses that can be used for local multicast in the range of addresses between 224.0.0.0 and 224.0.0.255. We will use 224.0.0.5 in the two example programs. These are local addresses that are invisible to the the Internet.

Multicast Broadcast Server

The following example is very similar to that seen two sections ago (Java class UDPServer) except we do not wait for a client request.

1 package com.markwatson.iot;

2

3 import java.io.IOException;

4 import java.net.*;

5

6 public class MulticastServer {

7

8 final static String INET_ADDR = "224.0.0.5";

9 final static int PORT = 9002;

10

11 public static void main(String[] args)

12 throws IOException, InterruptedException {

13 InetAddress addr = InetAddress.getByName(INET_ADDR);

14 DatagramSocket serverSocket = new DatagramSocket();

15 for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

16 String message = "message " + i;

17

18 DatagramPacket messagePacket =

19 new DatagramPacket(message.getBytes(),

20 message.getBytes().length, addr, PORT);

21 serverSocket.send(messagePacket);

22

23 System.out.println("broadcast message sent: " + message);

24 Thread.sleep(500);

25 }

26 }

27 }

In line 13 we create an INET address for “224.0.0.5” and in line 14 create a DatagramSocket that is reused for broadcasting 10 messages with a time delay of 1/2 a second between messages. The broadcast messages are defined in line 16 and the code in lines 18 to 21 creates a new DatagramPacket with the message text data and gets broadcast to the local network in line 21.

Running this example produces the following output (output edited for brevity):

Unlike the UDPServer example two sections ago, you will get this output regardless of whether you are running the listing client in the next section.

Multicast Broadcast Listener

The example in this section listens for broadcasts by the server example in the last section. The broadcast server and clients need to agree on the INET address and a port number (9002 in these examples).

1 package com.markwatson.iot;

2

3 import java.io.IOException;

4 import java.net.DatagramPacket;

5 import java.net.InetAddress;

6 import java.net.MulticastSocket;

7 import java.net.UnknownHostException;

8

9 public class MulticastClient {

10

11 final static String INET_ADDR = "224.0.0.5";

12 final static int PORT = 9002;

13

14 public static void main(String[] args) throws IOException {

15 InetAddress address = InetAddress.getByName(INET_ADDR);

16 byte[] buf = new byte[512]; // more than enough for any UDP style packet

17 MulticastSocket clientSocket = new MulticastSocket(PORT);

18 // listen for broadcast messages:

19 clientSocket.joinGroup(address);

20

21 while (true) {

22 DatagramPacket messagePacket = new DatagramPacket(buf, buf.length);

23 clientSocket.receive(messagePacket);

24

25 String message = new String(buf, 0, buf.length);

26 System.out.println("received broadcast message: " + message);

27 }

28 }

29 }

The client creates an InetAddress in line 15 and allocates storage for the received text messages in line 16. We create a MulticastSocket on port 9002 in line 17 and in line 19 join the broadcast server’s group. In lines 21 through 27 we loop forever listening for broadcast messages and printing them out.

Running this example produces the following output (output edited for brevity):

Wrap Up on IoT

Even though I personally have some concerns about security and privacy for IoT applications and products, I am enthusiastic about the possibilities of making our lives simpler and more productive with small networked devices. When we work and play we want as much as possible to not think about our computing devices so that we can concentrate on our activities.

I have barely scratched the surface on useful IoT technologies in this chapter but I hope that I have shown you network programming techniques that you can use in your projects (IoT and also networked game programming). As I write this book there are companies supplying IoT hardware development kits and deciding on one kit and software framework and creating your own projects is a good way to proceed.