Linked Data

This chapter introduces you to techniques for information architecture and development using linked data and semantic web technologies. This chapter is paired with the next chapter on knowledge management so please read these two chapters in order.

Note: I published “Practical Semantic Web and Linked Data Applications: Java, JRuby, Scala, and Clojure Edition” and you can get a free PDF of this book here. While the technical details of that book are still relevant, I am now more opinionated about which linked data and semantic web technologies are most useful so this chapter is more focused. With some improvements, I use the Java client code for DBPedia search and SPARQL queries from my previous book. I also include new versions that return query results as JSON. I am going to assume that you have fetched a free copy of my book “Practical Semantic Web and Linked Data Applications” and use chapters 6 and 7 for an introduction to the Resource Definition Language (RDF and RDFS) and chapter 8 for a tutorial on the SPARQL query language. It is okay to read this background material later if you want to dive right into the examples in this chapter. I do provide a quick introduction to SPARQL and RDF i the next section, but please do also get a free copy of my semantic web book for a longer treatment. We use the standard query language SPARQL to retrieve information from RDF data sources in much the same way that we use SQL to retrieve information from relational databases.

In this chapter we will look at consuming linked data using SPARQL queries against public RDF data stores and searching DBPedia. Using the code from the earlier chapter “Natural Language Processing Using OpenNLP” we will also develop an example application that annotates text by tagging entities with unique DBPedia URIs for the entities (we will use this example also in the next chapter in a code example for knowledge Management).

Why use linked data?

Before we jump into technical details I want to give you some motivation for why you might use linked data and semantic web technologies to organize and access information. Suppose that your company sells products to customers and your task is to augment the relational databases used for ordering, shipping, and customer data with a new system that needs to capture relationships between products, customers, and information sources on the web that might help both your customers and customer support staff increase the utility of your products to your customers.

Customers, products, and information sources are entities that will sometimes be linked with properties or relationships with other entities. This new data will be unstructured and you do not know ahead of time all of the relationships and what new types of entities that the new system will use. If you come from a relational database background using an sort of graph database might be uncomfortable at first. As motivation consider that Google uses its Knowledge Graph (I customized the Knowledge Graph when I worked at Google) for internal applications, to add value to search results, and to power Google Now. Facebook uses its Open Graph to store information about uses, user posts, and relationships between users and posted material. These graph data stores are key assets for Google and Facebook. Just because you don’t deal with huge amounts of data does not mean that the flexibility of graph data is not useful for your projects! We will use the DBPedia graph database in this chapter for the example programs. DBPedia (which Google used as core knowledge when developing their Knowledge Graph) is a rich information source for typed data for products, people, companies, places, etc. Connecting internal data in your organization to external data sources like DBPedia increases the utility of yor private data. You can make this data sharing relationship symmetrical by selectively publishing some of your internal data externally as linked data for the benefit of your customers and business partners.

The key idea is to design the shape of your information (what entities do you deal with and what types of properties or relationships exist between different types of entities), ingest data into a graph database with a plan for keeping everything up to date, and then provide APIs or a query language so application programmers can access this linked data when developing new applications. In this chapter we will use semantic web standards with the SPARQL query language to access data but these ideas should apply to using other graph databases like Neo4J or non-relational data stores like MongoDB or CouchDB.

Example Code

The examples for this chapter are set up to run either from the command line or using IntelliJ.

There are three examples in this chapter. If you want to try running the code before reading the rest of the chapter, run each maven test separately:

1 mvn test -Dtest=AnnotationTest

2 mvn test -Dtest=DBPediaTest

3 mvn test -Dtest=SparqlTest

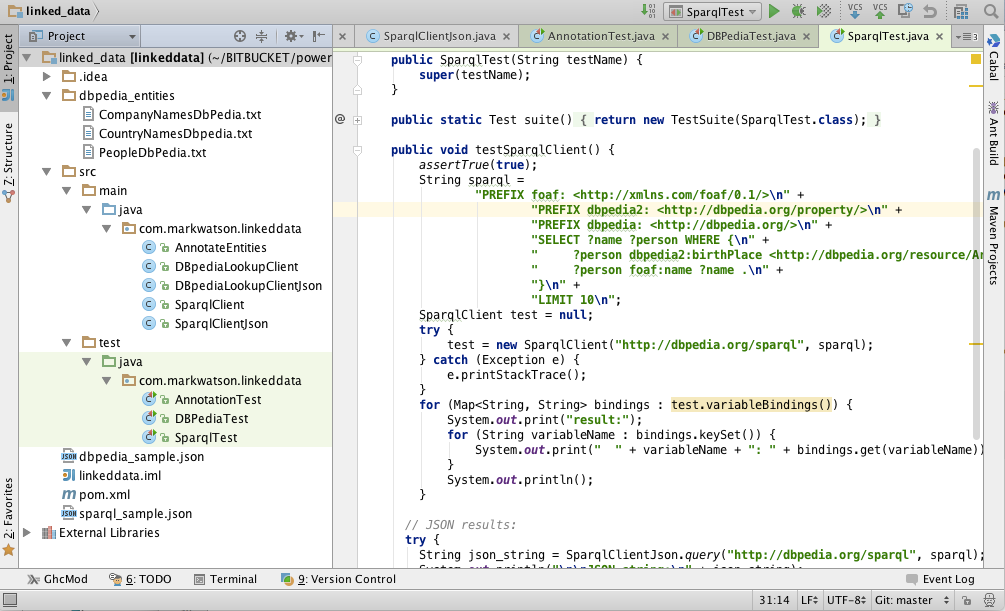

The following figure shows the project for this chapter in the Community Edition of IntelliJ:

Overview of RDF and SPARQL

The Resource Description Framework (RDF) is used to store information as subject/predicate/object triple values. RDF data was originally encoded as XML and intended for automated processing. In this chapter we will use two simple to read formats called “N-Triples” and “N3.” RDF data consists of a set of triple values:

- subject

- predicate

- object

As an example, suppose our application involved news stories and we wanted a way to store and query meta data. We might do this by extracting semantic information from the text, and storing it in RDF. I will use this application domain for the examples in this chapter. We might use triples like:

- subject: a URL (or URI) of a news article

- predicate: a relation like “containsPerson”

- object: a value like “Bill Clinton”

As previously mentioned, we will use either URIs or string literals as values for subjects and objects. We will always use URIs for the values of predicates. In any case URIs are usually preferred to string literals because they are unique. We will see an example of this preferred use but first we need to learn the N-Triple and N3 RDF formats.

Any part of a triple (subject, predicate, or object) is either a URI or a string literal. URIs encode namespaces. For example, the containsPerson predicate in the last example could properly be written as:

1 http://knowledgebooks.com/ontology/#containsPerson

The first part of this URI is considered to be the namespace for (what we will use as a predicate) “containsPerson.” When different RDF triples use this same predicate, this is some assurance to us that all users of this predicate subscribe to the same meaning. Furthermore, we will see in Section on RDFS that we can use RDFS to state equivalency between this predicate (in the namespace http://knowledgebooks.com/ontology/) with predicates represented by different URIs used in other data sources. In an “artificial intelligence” sense, software that we write does not understand a predicate like “containsPerson” in the way that a human reader can by combining understood common meanings for the words “contains” and “person” but for many interesting and useful types of applications that is fine as long as the predicate is used consistently. We will see shortly that we can define abbreviation prefixes for namespaces which makes RDF and RDFS files shorter and easier to read.

A statement in N-Triple format consists of three URIs (or string literals – any combination) followed by a period to end the statement. While statements are often written one per line in a source file they can be broken across lines; it is the ending period which marks the end of a statement. The standard file extension for N-Triple format files is *.nt and the standard format for N3 format files is *.n3.

My preference is to use N-Triple format files as output from programs that I write to save data as RDF. I often use Sesame to convert N-Triple files to N3 if I will be reading them or even hand editing them. You will see why I prefer the N3 format when we look at an example:

1 @prefix kb: <http://knowledgebooks.com/ontology#> .

2 <http://news.com/201234 /> kb:containsCountry "China" .

Here we see the use of an abbreviation prefix “kb:” for the namespace for my company KnowledgeBooks.com ontologies. The first term in the RDF statement (the subject) is the URI of a news article. The second term (the predicate) is “containsCountry” in the “kb:” namespace. The last item in the statement (the object) is a string literal “China.” I would describe this RDF statement in English as, “The news article at URI http://news.com/201234 mentions the country China.”

This was a very simple N3 example which we will expand to show additional features of the N3 notation. As another example, suppose that this news article also mentions the USA. Instead of adding a whole new statement like this:

1 @prefix kb: <http://knowledgebooks.com/ontology#> .

2 <http://news.com/201234 /> kb:containsCountry "China" .

3 <http://news.com/201234 /> kb:containsCountry "USA" .

we can combine them using N3 notation. N3 allows us to collapse multiple RDF statements that share the same subject and optionally the same predicate:

1 @prefix kb: <http://knowledgebooks.com/ontology#> .

2 <http://news.com/201234 /> kb:containsCountry "China" ,

3 "USA" .

We can also add in additional predicates that use the same subject:

1 @prefix kb: <http://knowledgebooks.com/ontology#> .

2

3 <http://news.com/201234 /> kb:containsCountry "China" ,

4 "USA" .

5 kb:containsOrganization "United Nations" ;

6 kb:containsPerson "Ban Ki-moon" , "Gordon Brown" ,

7 "Hu Jintao" , "George W. Bush" ,

8 "Pervez Musharraf" ,

9 "Vladimir Putin" ,

10 "Mahmoud Ahmadinejad" .

This single N3 statement represents ten individual RDF triples. Each section defining triples with the same subject and predicate have objects separated by commas and ending with a period. Please note that whatever RDF storage system we use (we will be using Sesame) it makes no difference if we load RDF as XML, N-Triple, of N3 format files: internally subject, predicate, and object triples are stored in the same way and are used in the same way.

I promised you that the data in RDF data stores was easy to extend. As an example, let us assume that we have written software that is able to read online news articles and create RDF data that captures some of the semantics in the articles. If we extend our program to also recognize dates when the articles are published, we can simply reprocess articles and for each article add a triple to our RDF data store using a form like:

1 <http://news.com/201234 /> kb:datePublished

2 "2008-05-11" .

Furthermore, if we do not have dates for all news articles that is often acceptable depending on the application.

SPARQL is a query language used to query RDF data stores. While SPARQL may initially look like SQL, there are some important differences like support for RDFS and OWL inferencing. We will cover the basics of SPARQL in this section.

We will use the following sample RDF data for the discusion in this section:

1 @prefix kb: <http://knowledgebooks.com/ontology#> .

2 @prefix rdfs: <http://www.w3.org/2000/01/rdf-schema#> .

3

4 kb:containsCity rdfs:subPropertyOf kb:containsPlace .

5

6 kb:containsCountry rdfs:subPropertyOf kb:containsPlace .

7

8 kb:containsState rdfs:subPropertyOf kb:containsPlace .

9

10 <http://yahoo.com/20080616/usa_flooding_dc_16 />

11 kb:containsCity "Burlington" , "Denver" ,

12 "St. Paul" ," Chicago" ,

13 "Quincy" , "CHICAGO" ,

14 "Iowa City" ;

15 kb:containsRegion "U.S. Midwest" , "Midwest" ;

16 kb:containsCountry "United States" , "Japan" ;

17 kb:containsState "Minnesota" , "Illinois" ,

18 "Mississippi" , "Iowa" ;

19 kb:containsOrganization "National Guard" ,

20 "U.S. Department of Agriculture" ,

21 "White House" ,

22 "Chicago Board of Trade" ,

23 "Department of Transportation" ;

24 kb:containsPerson "Dena Gray-Fisher" ,

25 "Donald Miller" ,

26 "Glenn Hollander" ,

27 "Rich Feltes" ,

28 "George W. Bush" ;

29 kb:containsIndustryTerm "food inflation" , "food" ,

30 "finance ministers" ,

31 "oil" .

32

33 <http://yahoo.com/78325/ts_nm/usa_politics_dc_2 />

34 kb:containsCity "Washington" , "Baghdad" ,

35 "Arlington" , "Flint" ;

36 kb:containsCountry "United States" ,

37 "Afghanistan" ,

38 "Iraq" ;

39 kb:containsState "Illinois" , "Virginia" ,

40 "Arizona" , "Michigan" ;

41 kb:containsOrganization "White House" ,

42 "Obama administration" ,

43 "Iraqi government" ;

44 kb:containsPerson "David Petraeus" ,

45 "John McCain" ,

46 "Hoshiyar Zebari" ,

47 "Barack Obama" ,

48 "George W. Bush" ,

49 "Carly Fiorina" ;

50 kb:containsIndustryTerm "oil prices" .

51

52 <http://yahoo.com/10944/ts_nm/worldleaders_dc_1 />

53 kb:containsCity "WASHINGTON" ;

54 kb:containsCountry "United States" , "Pakistan" ,

55 "Islamic Republic of Iran" ;

56 kb:containsState "Maryland" ;

57 kb:containsOrganization "University of Maryland" ,

58 "United Nations" ;

59 kb:containsPerson "Ban Ki-moon" , "Gordon Brown" ,

60 "Hu Jintao" , "George W. Bush" ,

61 "Pervez Musharraf" ,

62 "Vladimir Putin" ,

63 "Steven Kull" ,

64 "Mahmoud Ahmadinejad" .

65

66 <http://yahoo.com/10622/global_economy_dc_4 />

67 kb:containsCity "Sao Paulo" , "Kuala Lumpur" ;

68 kb:containsRegion "Midwest" ;

69 kb:containsCountry "United States" , "Britain" ,

70 "Saudi Arabia" , "Spain" ,

71 "Italy" , India" ,

72 ""France" , "Canada" ,

73 "Russia" , "Germany" , "China" ,

74 "Japan" , "South Korea" ;

75 kb:containsOrganization "Federal Reserve Bank" ,

76 "European Union" ,

77 "European Central Bank" ,

78 "European Commission" ;

79 kb:containsPerson "Lee Myung-bak" , "Rajat Nag" ,

80 "Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva" ,

81 "Jeffrey Lacker" ;

82 kb:containsCompany "Development Bank Managing" ,

83 "Reuters" ,

84 "Richmond Federal Reserve Bank" ;

85 kb:containsIndustryTerm "central bank" , "food" ,

86 "energy costs" ,

87 "finance ministers" ,

88 "crude oil prices" ,

89 "oil prices" ,

90 "oil shock" ,

91 "food prices" ,

92 "Finance ministers" ,

93 "Oil prices" , "oil" .

In the following examples, we will look at queries but not the results. We will start with a simple SPARQL query for subjects (news article URLs) and objects (matching countries) with the value for the predicate equal to $containsCountry$:

1 SELECT ?subject ?object

2 WHERE {

3 ?subject

4 http://knowledgebooks.com/ontology#containsCountry>

5 ?object .

6 }

Variables in queries start with a question mark character and can have any names. We can make this query easier and reduce the chance of misspelling errors by using a namespace prefix:

1 PREFIX kb: <http://knowledgebooks.com/ontology#>

2 SELECT ?subject ?object

3 WHERE {

4 ?subject kb:containsCountry ?object .

5 }

We could have filtered on any other predicate, for instance $containsPlace$. Here is another example using a match against a string literal to find all articles exactly matching the text “Maryland.” The following queries were copied from Java source files and were embedded as string literals so you will see quotation marks backslash escaped in these examples. If you were entering these queries into a query form you would not escape the quotation marks.

1 PREFIX kb: <http://knowledgebooks.com/ontology#>

2 SELECT ?subject

3 WHERE { ?subject kb:containsState \"Maryland\" . }

We can also match partial string literals against regular expressions:

1 PREFIX kb:

2 SELECT ?subject ?object

3 WHERE {

4 ?subject

5 kb:containsOrganization

6 ?object FILTER regex(?object, \"University\") .

7 }

Prior to this last example query we only requested that the query return values for subject and predicate for triples that matched the query. However, we might want to return all triples whose subject (in this case a news article URI) is in one of the matched triples. Note that there are two matching triples, each terminated with a period:

1 PREFIX kb: <http://knowledgebooks.com/ontology#>

2 SELECT ?subject ?a_predicate ?an_object

3 WHERE {

4 ?subject

5 kb:containsOrganization

6 ?object FILTER regex(?object, \"University\") .

7

8 ?subject ?a_predicate ?an_object .

9 }

10 DISTINCT

11 ORDER BY ?a_predicate ?an_object

12 LIMIT 10

13 OFFSET 5

When WHERE clauses contain more than one triple pattern to match, this is equivalent to a Boolean “and” operation. The DISTINCT clause removes duplicate results. The ORDER BY clause sorts the output in alphabetical order: in this case first by predicate (containsCity, containsCountry, etc.) and then by object. The LIMIT modifier limits the number of results returned and the OFFSET modifier sets the number of matching results to skip.

We are finished with our quick tutorial on using the SELECT query form. There are three other query forms that I am not covering in this chapter:

- CONSTRUCT – returns a new RDF graph of query results

- ASK – returns Boolean true or false indicating if a query matches any triples

- DESCRIBE – returns a new RDF graph containing matched resources

SPARQL Query Client

There are many available public RDF data sources. Some examples of publicly available SPARQL endpoints are:

- DBPedia which encodes the structured information in Wikipedia info boxes as RDF data. The DBPedia data is also available as a free download for hosting on your own SPARQL endpoint.

- LinkDb Which contains human genome data

- Library of Congress There is currently no SPARQL endpoint provided but subject matter Sparql data is available for download for use on your own SPARQL endpoint and there is a search faclity that can return RDF data results.

- BBC Programs and Music

- FactForge Combines RDF data from a many sources including DBPedia, Geonames, Wordnet, and Freebase. The SPARQL query page has many great examples to get you started. For example, look at the SPARQL for the query and results for “Show the distance from London of airports located at most 50 miles away from it.”

There are many public SPARQL endpoints on the web but I need to warn you that they are not always available. The raw RDF data for most public endpoints is usually available so if you are building a system relying on a public data set you should consider hosting a copy of the data on one of your own servers. I usually use one of the following RDF repositories and SPARQL query interfaces: Star Dog, Virtuoso, and Sesame. That said, there are many other fine RDF repository server options, both commercial and open source. After reading this chapter, you may want to read a fairly recent blog article I wrote for importing and using the OpenCYC world knowledge base in to a local repository.

In the next two sections you will learn how to make SPARQL queries against RDF data stores on the web, getting results both as JSON and parsed out to Java data values. A major theme in the next chapter is combining data in the “cloud” with local data.

JSON Client

1 package com.markwatson.linkeddata;

2

3 import org.apache.http.HttpResponse;

4 import org.apache.http.client.methods.HttpGet;

5 import org.apache.http.impl.client.DefaultHttpClient;

6

7 import java.io.BufferedReader;

8 import java.io.InputStreamReader;

9 import java.net.URLEncoder;

10

11 public class SparqlClientJson {

12 public static String query(String endpoint_URL, String sparql)

13 throws Exception {

14 StringBuffer sb = new StringBuffer();

15 try {

16 org.apache.http.client.HttpClient httpClient =

17 new DefaultHttpClient();

18 String req = URLEncoder.encode(sparql, "utf-8");

19 HttpGet getRequest =

20 new HttpGet(endpoint_URL + "?query=" + req);

21 getRequest.addHeader("accept", "application/json");

22 HttpResponse response = httpClient.execute(getRequest);

23 if (response.getStatusLine().getStatusCode() != 200)

24 return "Server error";

25

26 BufferedReader br =

27 new BufferedReader(

28 new InputStreamReader(

29 (response.getEntity().getContent())));

30 String line;

31 while ((line = br.readLine()) != null) {

32 sb.append(line);

33 }

34 httpClient.getConnectionManager().shutdown();

35 } catch (Exception e) {

36 e.printStackTrace();

37 }

38 return sb.toString();

39 }

40 }

We will be using the SPARQL query for finding people who were born in Arizona:

1 PREFIX foaf: <http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/>

2 PREFIX dbpedia2: <http://dbpedia.org/property/>

3 PREFIX dbpedia: <http://dbpedia.org/>

4 SELECT ?name ?person WHERE {

5 ?person dbpedia2:birthPlace <http://dbpedia.org/resource/Arizona> .

6 ?person foaf:name ?name .

7 }

8 LIMIT 10

You can run the unit tests for the DBPedia lookups and SPARQL queries using:

1 mvn test -Dtest=DBPediaTest

Here is a small bit of the output produced when running the unit test for this class with this example SPARQL query:

{

"head": {

"link": [],

"vars": [

"name",

"person"

]

},

"results": {

"distinct": false,

"ordered": true,

"bindings": [

{

"name": {

"type": "literal",

"xml:lang": "en",

"value": "Ryan David Jahn"

},

"person": {

"type": "uri",

"value": "http://dbpedia.org/resource/Ryan_David_Jahn"

}

},

...

]

...

},

}

This example uses the DBPedia SPARQL endpoint. There is another public DBPedia service for looking up names and we will look at it in the next section.

DBPedia Entity Lookup

Later in this chapter I will show you what the raw DBPedia data looks like. For this section we will access DBPdedia through a public search API. The following two sub-sections show example code for getting the DBPedia lookup results as Java data and as JSON data.

Java Data Client

In the DBPedia Lookup service that we use in this section I only list a bit of the example program for this section. This example is fairly long and I refer you to the source code.

1 public class DBpediaLookupClient extends DefaultHandler {

2 public DBpediaLookupClient(String query) throws Exception {

3 this.query = query;

4 HttpClient client = new HttpClient();

5

6 String query2 = query.replaceAll(" ", "+");

7 HttpMethod method =

8 new GetMethod(

9 "http://lookup.dbpedia.org/api/search.asmx/KeywordSearch?QueryString="\

10 +

11 query2);

12 try {

13 client.executeMethod(method);

14 InputStream ins = method.getResponseBodyAsStream();

15 SAXParserFactory factory = SAXParserFactory.newInstance();

16 SAXParser sax = factory.newSAXParser();

17 sax.parse(ins, this);

18 } catch (HttpException he) {

19 System.err.println("Http error connecting to lookup.dbpedia.org");

20 } catch (IOException ioe) {

21 System.err.println("Unable to connect to lookup.dbpedia.org");

22 }

23 method.releaseConnection();

24 }

25

26 public void printResults(List<Map<String, String>> results) {

27 for (Map<String, String> result : results) {

28 System.out.println("\nNext result:\n");

29 for (String key : result.keySet()) {

30 System.out.println(" " + key + "\t:\t" + result.get(key));

31 }

32 }

33 }

34

35 // ... XML parsing code not shown ...

36

37 public List<Map<String, String>> variableBindings() {

38 return variableBindings;

39 }

40 }

The DBPedia Lookup service returns XML response data by default. The DBpediaLookupClient class is fairly simple. It encodes a query string, calls the web service, and parses the XML payload that is returned from the service.

You can run the unit tests for the DBPedia lookups and SPARQL queries using:

1 mvn test -Dtest=DBPediaTest

Sample output for looking up “London” showing values for map key “Description”, “Label”, and “URI” in the fetched data looks like:

1 Description : The City of London was a United Kingdom Parliamentary constituen\

2 cy. It was a constituency of the House of Commons of the Parliament of England t\

3 hen of the Parliament of Great Britain from 1707 to 1800 and of the Parliament o\

4 f the United Kingdom from 1801 to 1950. The City of London was a United Kingdom \

5 Parliamentary constituency. It was a constituency of the House of Commons of the\

6 Parliament of England then of the Parliament of Great Britain from 1707 to 1800\

7 and of the Parliament of the United Kingdom from 1801 to 1950.

8 Label : United Kingdom Parliamentary constituencies established in 1298

9 URI : http://dbpedia.org/resource/City_of_London_(UK_Parliament_constituency)

If you run this example program you will see that the description text prints all on one line; it line wraps in the about example.

This example returns a list of maps as a result where each list item is a map which each key is a variable name and each map value is the value for the key. In the next section we will look at similar code that instead returns JSON data.

JSON Client

The example in the section is simpler than the one in the last section because we just need to return the payload from the lookup web service as-is (i.e., as JSON data encoded in a string).

1 package com.markwatson.linkeddata;

2

3 import org.apache.http.HttpResponse;

4 import org.apache.http.client.HttpClient;

5 import org.apache.http.client.methods.HttpGet;

6 import org.apache.http.impl.client.DefaultHttpClient;

7

8 import java.io.BufferedReader;

9 import java.io.InputStreamReader;

10

11 /**

12 * Copyright 2015 Mark Watson. Apache 2 license.

13 */

14 public class DBpediaLookupClientJson {

15 public static String lookup(String query) {

16 StringBuffer sb = new StringBuffer();

17 try {

18 HttpClient httpClient = new DefaultHttpClient();

19 String query2 = query.replaceAll(" ", "+");

20 HttpGet getRequest =

21 new HttpGet(

22 "http://lookup.dbpedia.org/api/search.asmx/KeywordSearch?QueryString="

23 + query2);

24 getRequest.addHeader("accept", "application/json");

25 HttpResponse response = httpClient.execute(getRequest);

26

27 if (response.getStatusLine().getStatusCode() != 200) return "Server error";

28

29 BufferedReader br =

30 new BufferedReader(

31 new InputStreamReader((response.getEntity().getContent())));

32 String line;

33 while ((line = br.readLine()) != null) {

34 sb.append(line);

35 }

36 httpClient.getConnectionManager().shutdown();

37 } catch (Exception e) {

38 e.printStackTrace();

39 }

40 return sb.toString();

41 }

42 }

You can run the unit tests for the DBPedia lookups and SPARQL queries using:

1 mvn test -Dtest=DBPediaTest

The following example for the lookup for “Bill Clinton” shows sample JSON (as a string) content that I “pretty printed” using IntelliJ for readability:

{

"results": [

{

"uri": "http://dbpedia.org/resource/Bill_Clinton",

"label": "Bill Clinton",

"description": "William Jefferson \"Bill\" Clinton (born William Jefferson\

Blythe III; August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd P\

resident of the United States from 1993 to 2001. Inaugurated at age 46, he was t\

he third-youngest president. He took office at the end of the Cold War, and was \

the first president of the baby boomer generation. Clinton has been described as\

a New Democrat. Many of his policies have been attributed to a centrist Third W\

ay philosophy of governance.",

"refCount": 7034,

"classes": [

{

"uri": "http://dbpedia.org/ontology/OfficeHolder",

"label": "office holder"

},

{

"uri": "http://dbpedia.org/ontology/Person",

"label": "person"

},

...

],

"categories": [

{

"uri": "http://dbpedia.org/resource/Category:Governors_of_Arkansas",

"label": "Governors of Arkansas"

},

{

"uri": "http://dbpedia.org/resource/Category:American_memoirists",

"label": "American memoirists"

},

{

"uri": "http://dbpedia.org/resource/Category:Spouses_of_United_States_\

Cabinet_members",

"label": "Spouses of United States Cabinet members"

},

...

],

"templates": [],

"redirects": []

},

Annotate Text with DBPedia Entity URIs

I have used DBPdedia, the semantic web/linked data version of Wikipedia, in several projects. One useful use case is using DBPedia URIs as a unique identifier of a unique real world entity. For example, there are many people named Bill Clinton but usually this name refers to a President of the USA. It is useful to annotate people’s names, company names, etc. in text with the DBPedia URI for that entity. We will do this in a quick and dirty way (but hopefully still useful!) in this section and then solve the same problem in a different way in the next section.

In this section we simply look for exact matches in text for the descriptions for DBPedia URIs. In the next section we tokenize the descriptions and also tokenize the text to match entity names with URIs. I will also show you some samples of the raw DBPedia RDF data in the next section.

For one of my own projects I created mappings of entity names to DBPedia URIs for nine entity classes. For the example in this section I use three of my entity class mappings: people, countries, and companies. The data for these entity classes is stored in text files in the subdirectory dbpedia_entities. Later in this chapter I will show you what the raw DBPedia dump data looks like.

The example program in this section modified input text adding DBPedia URIs after entities recognized in the text.

The annotation code in the following example is simple but not very efficient. See the source code for comments discussing this that I left out of the following listing (edited to fit the page width):

1 package com.markwatson.linkeddata;

2

3 import java.io.BufferedReader;

4 import java.io.FileInputStream;

5 import java.io.InputStream;

6 import java.io.InputStreamReader;

7 import java.nio.charset.Charset;

8 import java.util.HashMap;

9 import java.util.Map;

10

11 public class AnnotateEntities {

12

13 /**

14 * @param text - input text to annotate with DBPedia URIs for entities

15 * @return original text with embedded annotations

16 */

17 static public String annotate(String text) {

18 String s = text.replaceAll("\\.", " !! ").replaceAll(",", " ,").

19 replaceAll(";", " ;").replaceAll(" ", " ");

20 for (String entity : companyMap.keySet())

21 if (s.indexOf(entity) > -1) s = s.replaceAll(entity, entity +

22 " (" + companyMap.get(entity) + ")");

23 for (String entity : countryMap.keySet())

24 if (s.indexOf(entity) > -1) s = s.replaceAll(entity, entity +

25 " (" + countryMap.get(entity) + ")");

26 for (String entity : peopleMap.keySet())

27 if (s.indexOf(entity) > -1) s = s.replaceAll(entity, entity +

28 " (" + peopleMap.get(entity) + ")");

29 return s.replaceAll(" !!", ".");

30 }

31

32 static private Map<String, String> companyMap = new HashMap<>();

33 static private Map<String, String> countryMap = new HashMap<>();

34 static private Map<String, String> peopleMap = new HashMap<>();

35 static private void loadMap(Map<String, String> map, String entityFilePath) {

36 try {

37 InputStream fis = new FileInputStream(entityFilePath);

38 InputStreamReader isr =

39 new InputStreamReader(fis, Charset.forName("UTF-8"));

40 BufferedReader br = new BufferedReader(isr);

41 String line = null;

42 while ((line = br.readLine()) != null) {

43 int index = line.indexOf('\t');

44 if (index > -1) {

45 String name = line.substring(0, index);

46 String uri = line.substring((index + 1));

47 map.put(name, uri);

48 }

49 }

50 } catch (Exception ex) {

51 ex.printStackTrace();

52 }

53 }

54 static {

55 loadMap(companyMap, "dbpedia_entities/CompanyNamesDbPedia.txt");

56 loadMap(countryMap, "dbpedia_entities/CountryNamesDbPedia.txt");

57 loadMap(peopleMap, "dbpedia_entities/PeopleDbPedia.txt");

58 }

59 }

If you run the unit tests for this code the output looks like:

1 > mvn test -Dtest=AnnotationTest

2 [INFO] Compiling 5 source files to /Users/markw/BITBUCKET/power-java/linked_data\

3 /target/classes

4

5 -------------------------------------------------------

6 T E S T S

7 -------------------------------------------------------

8 Running com.markwatson.linkeddata.AnnotationTest

9

10 Annotated string: Bill Clinton (<http://dbpedia.org/resource/Bill_Clinton>) went\

11 to a charity event in Thailand (<http://dbpedia.org/resource/Thailand>).

12

13 Tests run: 1, Failures: 0, Errors: 0, Skipped: 0, Time elapsed: 0.251 sec

14

15 Results :

16

17 Tests run: 1, Failures: 0, Errors: 0, Skipped: 0

Resolving Named Entities in Text to Wikipedia URIs

We will solve the same problem in this section as we looked at in the last section: resolving named entities with DBPedia (Wikipedia) URIs but we will use an alternative approach.

I some of my work I find it useful to resolve named entities (e.g., people, organizations, products, locations, etc.) in text to unique DBPedia URIs. The DBPedia semantic web data, which we will also discuss in the next chapter, is derived from the “info boxes” in Wikipedia articles. I find DBPedia to be an incredibly useful knowledge source. When I worked at Google with the Knowledge Graph we were using a core of knowledge from Wikipedia/DBPedia and Freebase with a lot of other information sources. DBPedia is already (reasonably) clean data and is ready to be used as-is in your applications.

The idea behind the example in this chapter is simple: the RDF data dumps from DBPedia can be processed to capture an entity name and the corresponding DBPedia entity URI.

The raw DPBedia files can be downloaded from Resolving Named Entities (latest version when I wrote this chapter) and as an example, the SKOS categories dataset looks like (reformatted to be a litle easier to read):

1 <http://dbpedia.org/resource/Category:World_War_II>

2 <http://www.w3.org/2004/02/skos/core#broader>

3 <http://dbpedia.org/resource/Category:Conflicts_in_1945> .

4

5 <http://dbpedia.org/resource/Category:World_War_II>

6 <http://www.w3.org/2004/02/skos/core#broader>

7 <http://dbpedia.org/resource/Category:Global_conflicts> .

8

9 <http://dbpedia.org/resource/Category:World_War_II>

10 <http://www.w3.org/2004/02/skos/core#broader>

11 <http://dbpedia.org/resource/Category:Modern_Europe> .

12

13 <http://dbpedia.org/resource/Category:World_War_II>

14 <http://www.w3.org/2004/02/skos/core#broader>

15 <http://dbpedia.org/resource/Category:The_World_Wars> .

SKOS (Simple Knowledge Organization System) defines hierarchies of categories that are useful for categorizing real world entities, actions, etc. Cateorgies are then used for RDF versions of Wikipedia article titles, abstracts, geographic data, etc. Here is a small sample of RDF that maps subject URIs to text labels:

1 <http://dbpedia.org/resource/Abraham_Lincoln>

2 <http://www.w3.org/2000/01/rdf-schema#label>

3 "Abraham Lincoln"@en .

4

5 <http://dbpedia.org/resource/Alexander_the_Great>

6 <http://www.w3.org/2000/01/rdf-schema#label>

7 "Alexander the Great"@en .

8

9 <http://dbpedia.org/resource/Ballroom_dancing>

10 <http://www.w3.org/2000/01/rdf-schema#label>

11 "Ballroom dancing"@en .

As a final example of what the raw DBPedia RDF dump data looks like, here are some RDF statements that define abstracts for articles (text descriptions are shortened in the following listing to fit on one line):

1 <http://dbpedia.org/resource/An_American_in_Paris>

2 <http://www.w3.org/2000/01/rdf-schema#comment>

3 "An American in Paris is a jazz-influenced symphonic poem by ...."@en .

4

5 <http://dbpedia.org/resource/Alberta>

6 <http://www.w3.org/2000/01/rdf-schema#comment>

7 "Alberta (is a western province of Canada. With a population of 3,645,257 ...."\

8 @en .

I have already pulled entity names and URIs for nine classes of entities and this data is available in the github repo for this book in the directory inked_data/dbpedia_entities.

Java Named Entity Recognition Library

We already saw the use of Named Entity Resolution (NER) in the chapter using OpenNLP. Here we do something different. For my own projects I have data that I have processed that maps entity names to DBPedia URIs and Clojure code to use this data. For the purposes of this book, I am releasing my data under the Apache 2 license so you can use it in your projects and I converted my Clojure NER library to Java.

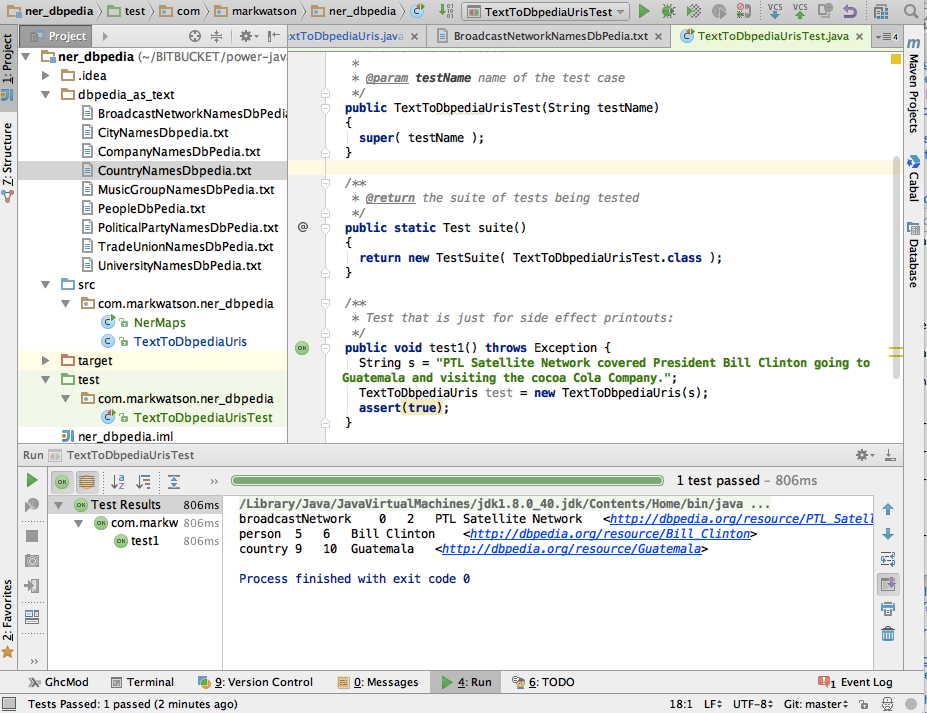

The following figure shows the project for this chapter in IntelliJ:

The following code example uses my data for mapping nine classes of entities to DBPedia URIs:

1 package com.markwatson.ner_dbpedia;

2

3 import java.io.IOException;

4 import java.nio.file.Files;

5 import java.nio.file.Paths;

6 import java.util.HashMap;

7 import java.util.Map;

8 import java.util.stream.Stream;

9

10 /**

11 * Created by markw on 10/12/15.

12 */

13 public class NerMaps {

14 private static Map<String, String> textFileToMap(String nerFileName) {

15 Map<String, String> ret = new HashMap<String, String>();

16 try {

17 Stream<String> lines =

18 Files.lines(Paths.get("dbpedia_as_text", nerFileName));

19 lines.forEach(line -> {

20 String[] tokens = line.split("\t");

21 if (tokens.length > 1) {

22 ret.put(tokens[0], tokens[1]);

23 }

24 });

25 lines.close();

26 } catch (Exception ex) {

27 ex.printStackTrace();

28 }

29 return ret;

30 }

31

32 static public final Map<String, String> broadcastNetworks =

33 textFileToMap("BroadcastNetworkNamesDbPedia.txt");

34 static public final Map<String, String> cityNames =

35 textFileToMap("CityNamesDbpedia.txt");

36 static public final Map<String, String> companyames =

37 textFileToMap("CompanyNamesDbPedia.txt");

38 static public final Map<String, String> countryNames =

39 textFileToMap("CountryNamesDbpedia.txt");

40 static public final Map<String, String> musicGroupNames =

41 textFileToMap("MusicGroupNamesDbPedia.txt");

42 static public final Map<String, String> personNames =

43 textFileToMap("PeopleDbPedia.txt");

44 static public final Map<String, String> politicalPartyNames =

45 textFileToMap("PoliticalPartyNamesDbPedia.txt");

46 static public final Map<String, String> tradeUnionNames =

47 textFileToMap("TradeUnionNamesDbPedia.txt");

48 static public final Map<String, String> universityNames =

49 textFileToMap("UniversityNamesDbPedia.txt");

50

51 public static void main(String[] args) throws IOException {

52 new NerMaps().textFileToMap("CityNamesDbpedia.txt");

53 }

54 }

The class TextToDbpediaUris uses the nine NER types defined in class NerMaps. In the following listing the code for all by the NER class Broadcast News Networks is not shown for brevity:

1 package com.markwatson.ner_dbpedia;

2

3 public class TextToDbpediaUris {

4 private TextToDbpediaUris() {

5 }

6

7 public TextToDbpediaUris(String text) {

8 String[] tokens = tokenize(text + " . . .");

9 String s = "";

10 for (int i = 0, size = tokens.length - 2; i < size; i++) {

11 String n2gram = tokens[i] + " " + tokens[i + 1];

12 String n3gram = n2gram + " " + tokens[i + 2];

13 // check for 3grams:

14 if ((s = NerMaps.broadcastNetworks.get(n3gram)) != null) {

15 log("broadcastNetwork", i, i + 2, n3gram, s);

16 i += 2;

17 continue;

18 }

19

20 // check for 2grams:

21 if ((s = NerMaps.broadcastNetworks.get(n2gram)) != null) {

22 log("broadCastNetwork", i, i + 1, n2gram, s);

23 i += 1;

24 continue;

25 }

26

27 // check for 1grams:

28 if ((s = NerMaps.broadcastNetworks.get(tokens[i])) != null) {

29 log("broadCastNetwork", i, i + 1, tokens[i], s);

30 continue;

31 }

32 }

33 }

34

35 /** In your applications you will want to subclass TextToDbpediaUris

36 * and override <strong>log</strong> to do something with the

37 * DBPedia entities that you have identified.

38 * @param nerType

39 * @param index1

40 * @param index2

41 * @param ngram

42 * @param uri

43 */

44 void log(String nerType, int index1, int index2, String ngram, String uri) {

45 System.out.println(nerType + "\t" + index1 + "\t" + index2 + "\t" + ngram + \

46 "\t" + uri);

47 }

48

49 private String[] tokenize(String s) {

50 return s.replaceAll("\\.", " \\. ").replaceAll(",", " , ")

51 .replaceAll("\\?", " ? ").replaceAll("\n", " ").replaceAll(";", " ; ").s\

52 plit(" ");

53 }

54 }

Here is an example showing how to use this code and the output:

String s = "PTL Satellite Network covered President Bill Clinton going to Gu\

atemala and visiting the Cocoa Cola Company.";

TextToDbpediaUris test = new TextToDbpediaUris(s);

The second and third values are word indices (first word in sequence and last word in sequence from the input tokenized text).

There are many types of applications that can benefit from using “real world” information from sources like DBPedia.

Combining Data from Public and Private Sources

A powerful idea is combining public and private linked data; for example, combining the vast real world knowledge stored in DBPedia with an RDF data store containing private data specific to your company. There are two ways to do this:

- Use SPARQL queries to join data from multiple SPARQL endpoints

- Assuming you have an RDF repository of private data, import external sources like DBPedia into your local data store

It is beyond the scope of my coverage of SPARQL but data can be joined from multiple endpoints using the SERVICE keyword in a SPARQL WHERE clause. In a similar way, public sources like DBPedia can be imported into your local RDF repository: this both makes queries more efficient and makes your system more robust in the face of failures of third party services.

One other data source that can be very useful to integrate into your applications is web search. I decided not to cover Java examples for calling public web search APIs in this book but I will refer you to my project on github that wraps the Microsoft Bing Search API. I mention this as an example pattern of using local data (notes and stored PDF documents) with public data APIs.

We will talk more about combining different data sources in the next chapter.

Wrap Up for Linked Data

The semantic web and linked data are large topics and my goal in this chapter was to provide an easy to follow introduction to hopefully interest you in the subject and motivate you for further study. If you have not seen graph data before then RDF likely seems a little strange to you. There are more general graph databases like the commercial Neo4j commercial product (a free community edition is available) which provides an alternative to RDF data stores. If you would like to experiment with running your own RDF data store and SPARQL endpoint there are many fine open source and commercial products to choose from. If you read my web blog you have seen my experiments using the free edition of the Stardog RDF data store.