Assorted Tips and Tricks

Change a line chart into a scatter plot

Confession time.

In the original book I didn’t actually intend to add in a section with a scatter plot in it for its own sake because I thought it would be;

- tricky

- not useful

- all of the above

I was wrong on all counts.

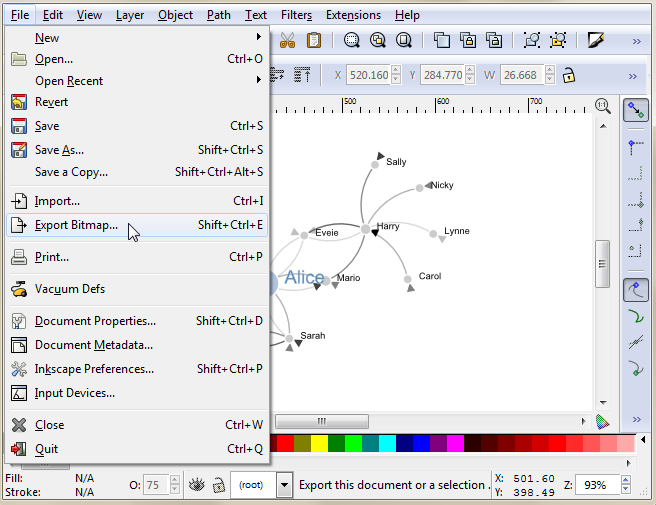

All we need to do is take the simple graph example file and slot the following block in between the ‘Add the valueline path’ and the ‘add the x axis’ blocks.

// add the dots

svg.selectAll("dot")

.data(data)

.enter().append("circle")

.attr("r", 5)

.attr("cx", function(d) { return x(d.date); })

.attr("cy", function(d) { return y(d.close); });

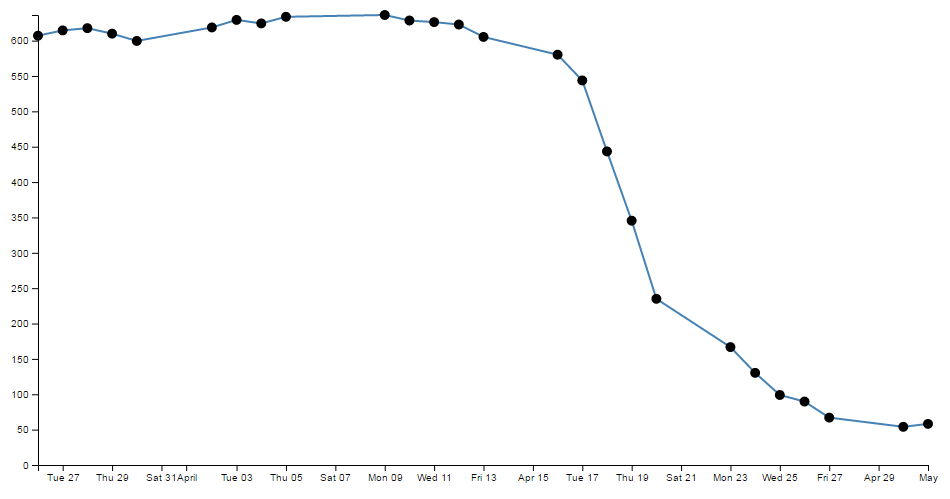

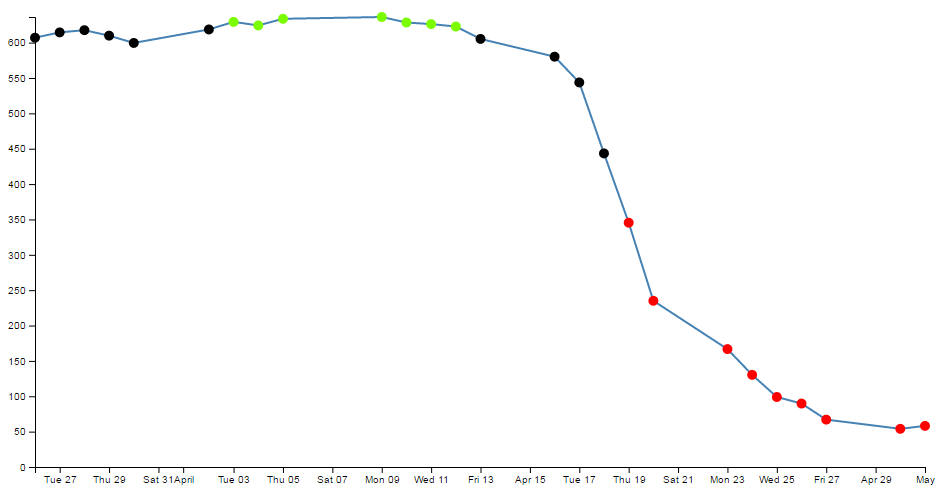

And we will get…

The full code for this graph can also be found on github or in the code samples bundled with this book (simple-scatterplot.html and data.csv). A live example can be found on bl.ocks.org.

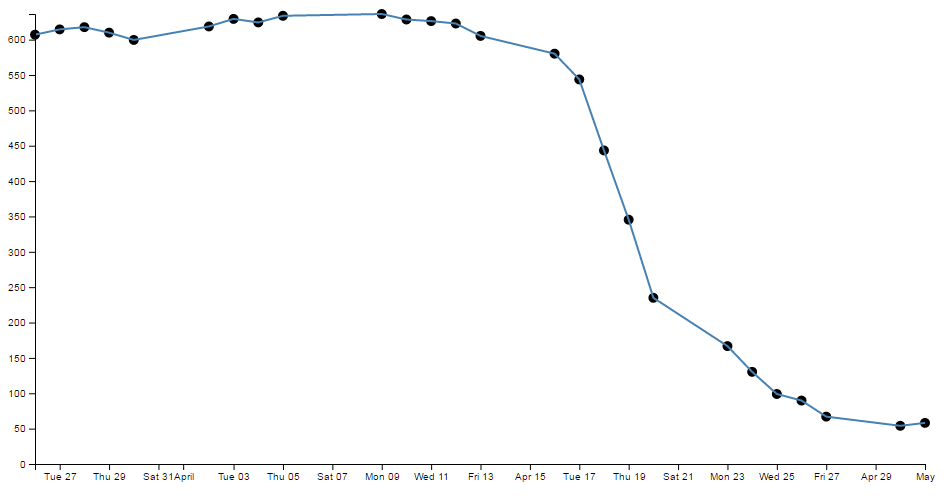

I deliberately put the dots after the line in the drawing section, because I thought they would look better, but we could put the block of code before the line drawing block to get the following effect;

(just trying to reinforce the concept that ‘order’ matters when drawing objects :-)).

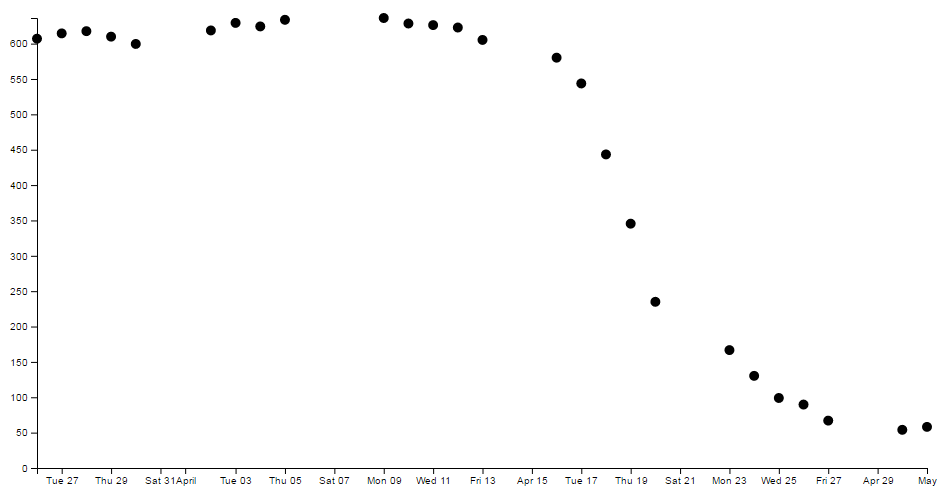

We could of course just remove the line block all together…

But in my humble opinion it loses something.

So what do the individual lines in the scatter plot block of JavaScript do?

The first line (svg.selectAll("dot")) essentially provides a suitable group label for the svg circle elements that will be added. The next line associates the range of data that we have to the group of elements we are about to add in.

Then we add a circle for each data point (.enter().append("circle")) with a radius of 5 pixels (.attr("r", 5)) and appropriate x (.attr("cx", function(d) { return x(d.date); })) and y (.attr("cy", function(d) { return y(d.close); });) coordinates.

There is lots more that we could be doing with this piece of code including varying the colour or size or opacity of the circles depending on the data and all sorts of really neat things, but for the mean time, there we go. Scatter plot!

Adding tooltips.

Tooltips have a marvellous duality. They are on one hand a pretty darned useful thing that aids in giving context and information where required and on the other hand, if done with a bit of care, they can look very stylish :-).

Technically, they represent a slight deviation from what we have been playing with so far into a mildly more complex arena of ‘transitions’ and ‘events’. You will probably regard this one of two ways. Either accepting that it just works and using it as shown, or you will actually know what’s going on in which case feel free to deride my efforts as those of a rank amateur :-).

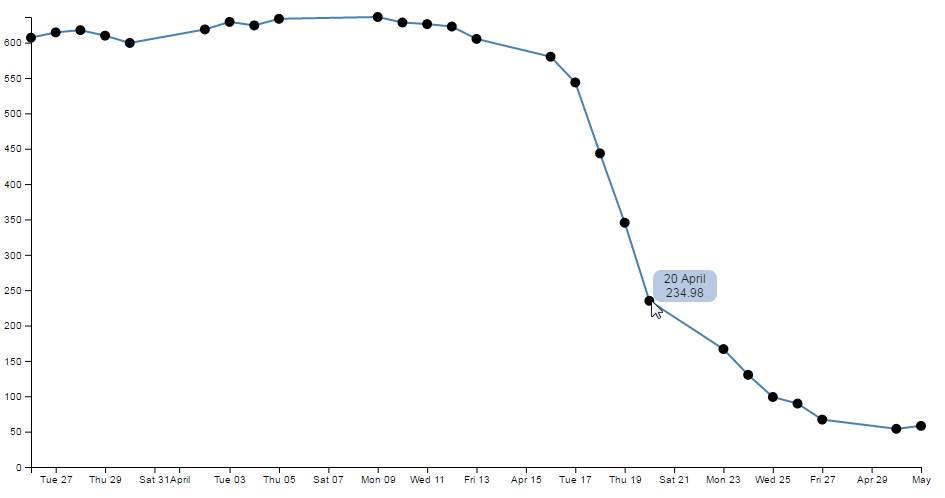

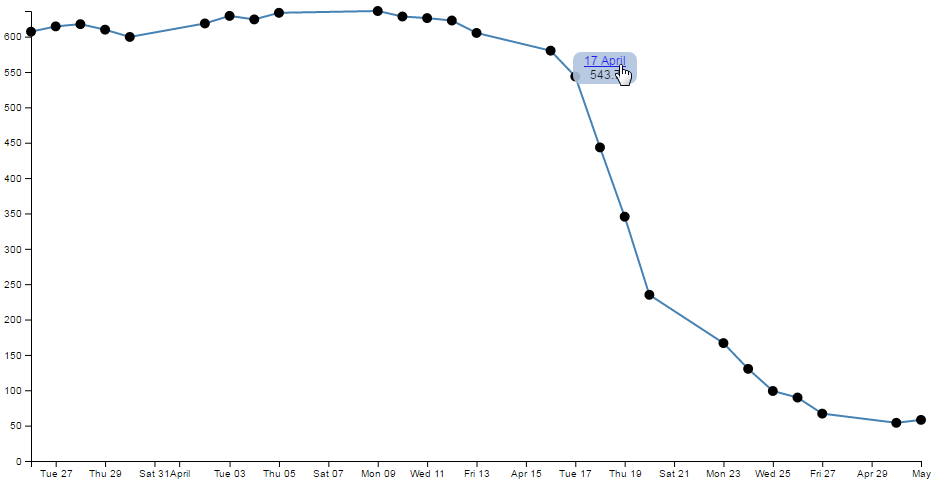

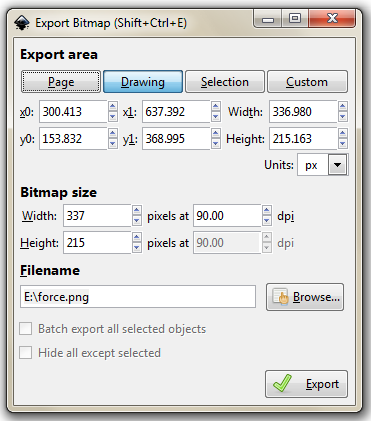

Just in case there is some confusion, a tooltip (one word or two?) is a discrete piece of information that will pop into view when the mouse hovers over somewhere specific. Most of us have seen and used them, but I suppose we all tend to call them different things such as ‘infotip’, ‘hint’ or ‘hover box’ I don’t know if there’s a right name for them, but here’s an example of what we’re trying to achieve;

We can see the mouse has hovered over one of the scatter plot circles and a tip has appeared that provides us with the exact date and value for that point.

We can also notice that there’s a certain degree of ‘fancy’ here as the information is bound by a rectangular shape with rounded corners and a slight opacity. The other piece of ‘fancy’ which you don’t see in a PDF (or whatever format this distinguished tome will be published in on its 33rd reprint in the year 2034), is that when these tool tips appear and disappear, they do so in an elegant fade-in, fade-out way. Pretty!

Before we get started describing how the code goes together, let’s take a quick look at the two technique specifics that I mentioned earlier, ‘transitions’ and ‘events’.

Transitions

From the main d3.js web page (d3js.org) transitions are described as gradually interpolating styles and attributes over time. So what I take that to mean is that if you want to change an object, you can do so by simply specifying the attribute / style end point that you want it to end up with and the time you want it to take and go!

Of course, it’s not quite that simple, but luckily, smarter people than I have done some fantastic work describing different aspects of transitions so please see the following for a more complete description of the topic;

- Mike Bostock’s Transition tutorial

- Christophe Viau’s ‘Try D3 Now!’ tutorial

Hopefully observing the mouseover and mouseout transitions in the tooltips example will whet your appetite for more!

Events

The other technique is related to mouse ‘events’. This describes the browser watching for when ‘something’ happens with the mouse on the screen and when it does, it takes a specified action. A (probably non-comprehensive) list of the types of events are the following;

- mousedown: Triggered by an element when a mouse button is pressed down over it

- mouseup: Triggered by an element when a mouse button is released over it

- mouseover: Triggered by an element when the mouse comes over it

- mouseout: Triggered by an element when the mouse goes out of it

- mousemove: Triggered by an element on every mouse move over it.

- click: Triggered by a mouse click: mousedown and then mouseup over an element

- contextmenu: Triggered by a right-button mouse click over an element.

- dblclick: Triggered by two clicks within a short time over an element

How many of these are valid to use within d3 I’m not sure, but I’m willing to bet that there are probably more than those here as well. Please go to http://javascript.info/tutorial/mouse-events for a far better description of the topic if required.

Get tipping

So, bolstered with a couple of new concepts to consider, let’s see how they are enacted in practice.

The full code for this graph can also be found on github or in the code samples bundled with the book (simple-tooltips.html and data.csv). A live example can be found on bl.ocks.org.

If we start with our simple-scatter plot graph there are 4 areas in it that we will want to modify (it may be easier to check the simple-tooltips.html file in the code samples bundled with this book).

The first area is the CSS. The following code should be added just before the </style> tag;

div.tooltip {

position: absolute;

text-align: center;

width: 60px;

height: 28px;

padding: 2px;

font: 12px sans-serif;

background: lightsteelblue;

border: 0px;

border-radius: 8px;

pointer-events: none;

}

These styles are defining how our tooltip will appear . Most of them are fairly straight forward. The position of the tooltip is done in absolute measurements, not relative. The text is centre aligned, the height, width and colour of the rectangle is 28px, 60px and lightsteelblue respectively. The ‘padding’ is an interesting feature that provides a neat way to grow a shape by a fixed amount from a specified size.

We set the border to 0px so that it doesn’t show up and a neat style (attribute?) called border-radius provides the nice rounded corners on the rectangle.

Lastly, but by no means least, the pointer-events: none line is in place to instruct the mouse event to go ‘through’ the element and target whatever is ‘underneath’ that element instead (Read more here). That means that even if the tooltip partly obscures the circle, the code will still act as if the mouse is only over the circle.

The second addition is a simple one-liner that should (for forms sake) be placed under the parseTime variable declaration;

var formatTime = d3.timeFormat("%e %B");

This line formats the date when it appears in our tooltip. Without it, the time would default to a disturbingly long combination of temporal details. In the case here we have declared that we want to see the day of the month (%e) and the full month name(%B).

The third block of code is the function declaration for ‘div’.

var div = d3.select("body").append("div")

.attr("class", "tooltip")

.style("opacity", 0);

We can place that just after the valueline definition in the JavaScript. Again there’s not too much here that’s surprising. We tell it to attach a div element to the body element, we set the class to the tooltip class (from the CSS) and we set the opacity to zero. It might sound strange to have the opacity set to zero, but remember, that’s the natural state of a tooltip. It will live unseen until it’s moment of revelation arrives and it pops up!

The final block of code is slightly more complex and could be described as a mutant version of the neat little bit of code that we used to do the drawing of the dots for the scatter plot. That’s because the tooltips are all about the scatter plot circles. Without a circle to ‘mouseover’, the tooltip never appears :-).

So here’s the code that includes the scatter plot drawing (it’s included since it’s pretty much integral);

// add the dots with tooltips

svg.selectAll("dot")

.data(data)

.enter().append("circle")

.attr("r", 5)

.attr("cx", function(d) { return x(d.date); })

.attr("cy", function(d) { return y(d.close); })

.on("mouseover", function(d) {

div.transition()

.duration(200)

.style("opacity", .9);

div.html(formatTime(d.date) + "<br/>" + d.close)

.style("left", (d3.event.pageX) + "px")

.style("top", (d3.event.pageY - 28) + "px");

})

.on("mouseout", function(d) {

div.transition()

.duration(500)

.style("opacity", 0);

});

The first six lines of the code are a repeat of the scatter plot drawing script. The only changes are that we’ve removed the semicolon from the cy attribute line since the code now has to carry on.

So the additions are broken into two areas that correspond to the two events. mouseover and mouseout. When the mouse moves over any of the circles in the scatter plot, the mouseover code is executed on the div element. When the mouse is moved off the circle a different set of instructions are executed.

on.mouseover

The .on("mouseover" line initiates the introduction of the tooltip. Then we declare the element we will be introducing (‘div’) and that we will be applying a transition to its introduction (.transition()). The next two lines describe the transition. It will take 200 milliseconds (.duration(200)) and will result in changing the element’s opacity to .9 (.style("opacity", .9);). Given that the natural state of our tooltip is an opacity of 0, this make sense for something appearing, but it doesn’t go all the way to a solid object and it retains a slight transparency just to make it look less permanent.

The following three lines format our tooltip. The first one adds an html element that contains our x and y information (the date and the close value). Now this is done in a slightly strange way. Other tooltips that I have seen have used a ‘.text’ element instead of a ‘.html’ one, but I have used ‘.html’ in this case because I wanted to include the line break tag <br/> to separate the date and value. I’m sure there are other ways to do it, but this worked for me. The other interesting part of this line is that this is where we call our time formatting function that we described earlier. The next two lines position the tooltip on the screen and to do this they grab the x and y coordinates of the mouse when the event takes place (with the d3.event.pageX and d3.event.pageY snippets) and apply a correction in the case of the y coordinate to raise the tooltip up by the same amount as its height (28 pixels).

on.mouseout

The .on("mouseout" section is slightly simpler in that it doesn’t have to do any fancy text / html / coordinate stuff. All it has to do is to fade out the ‘div’ element. And that is done by simply reversing the opacity back to 0 and setting the duration for the transition to 500 milliseconds (being slightly longer than the fade-in makes it look slightly cooler IMHO).

Right, there you go. As a description it’s ended up being a bit of a wall of text I’m afraid. But hopefully between the explanation and the example code you will get the idea. Please take the time to fiddle with the settings described here to find the ones that work for you and in the process you will reinforce some of the principles that help D3 do its thing.

Including an HTML link in a tool tip

There was an interesting question on d3noob.org about adding an HTML link to a tooltip. While the person asking the question had the problem pretty much solved already, I thought it might be useful for others.

The premise is that you want to add a tool tip to your visualization using the method described here, but you also want to include an HTML link in the tooltip that will link somewhere else. This might look a little like the following;

In the image above the date has been turned into a link. In this case the link goes to google.com, but that can obviously be configurable.

The full code for this example can be found on github or in the code samples bundled with this book (simple-tooltips-link.html and data.csv). A working example can be found on bl.ocks.org.

There are a few changes that we would want to make to our original tooltip code to implement this feature.

First of all, we’ll add the link to the date element. Adding an HTML link can be as simple as wrapping the ‘thing’ to be used as a link in <a> tags with an appropriate URL to go to.

The following adaptation of the code that prints the information into our tooltip code does just that;

div .html(

'<a href= "http://google.com">' + // The first <a> tag

formatTime(d.date) +

"</a>" + // closing </a> tag

"<br/>" + d.close)

.style("left", (d3.event.pageX) + "px")

.style("top", (d3.event.pageY - 28) + "px");

<a href= "http://google.com"> places our first <a> tag and declares the URL and the second tag follows after the date.

The second change we will want to make is to ensure that the tooltip stays in place long enough for us to actually click on the link. The problem being solved here is that our original code relies on the mouse being over the dot on the graph to display the tooltip. if the tooltip is displayed and the cursor moves to press the link, it will move off the dot on the graph and the tooltip vanishes (Darn!).

To solve the problem we can leave the tooltip in place adjacent to a dot while the mouse roams freely over the graph until the next time it reaches a dot and then the previous tooltip vanishes and a new one appears. The best way to appreciate this difference is to check out the live example on bl.ocks.org.

The code is as follows (you may notice that this also includes the link as described above);

// add the dots with tooltips

svg.selectAll("dot")

.data(data)

.enter().append("circle")

.attr("r", 5)

.attr("cx", function(d) { return x(d.date); })

.attr("cy", function(d) { return y(d.close); })

.on("mouseover", function(d) {

div.transition()

.duration(200)

.style("opacity", .9);

div .html(

'<a href= "http://google.com">' + // The first <a> tag

formatTime(d.date) +

"</a>" + // closing </a> tag

"<br/>" + d.close)

.style("left", (d3.event.pageX) + "px")

.style("top", (d3.event.pageY - 28) + "px");

});

We have removed the .on("mouseout" portion and moved the function that it used to carry out to the start of the .on("mouseover" portion. That way the first thing that occurs when the mouse cursor moves over a dot is that it removes the previous tooltip and then it places the new one.

The last change we need to make is to remove from the <style> section the line that told the mouse to ignore the tooltip;

Moar Links!

One link is interesting, but let’s face it, we didn’t go to all the trouble of putting a link into a tool tip to just go to one location. Now we shift it up a gear and start linking to different places depending on our data. At the same time (and because someone asked) we will make the link open in a new tab!

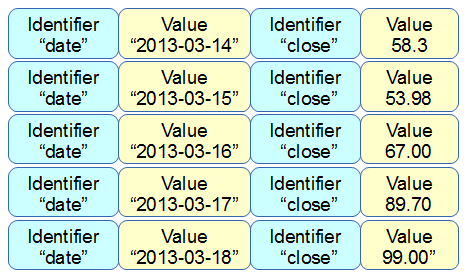

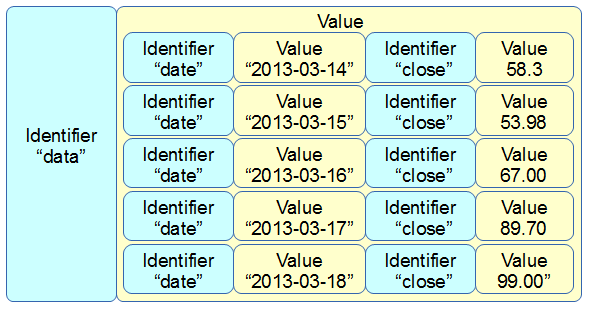

The changes to the script are fairly minor, but one fairly large change is the need to have links to go to. For this example I have added a range of links to visit to our csv file so it now looks like this;

The code change is to the piece of JavaScript where we add the HTML. This is what we end up with;

div .html(

'<a href= "'+d.link+'" target="_blank">' + //with a link

formatTime(d.date) +

"</a>" +

"<br/>" + d.close)

.style("left", (d3.event.pageX) + "px")

.style("top", (d3.event.pageY - 28) + "px");

We’ve replaced the URL http://google.com with the variable for our link column d.link and we’ve also added in the target="_blank" statement so that our link opens in a new tab.

The full code for this multi link example can be found on github or in the code samples bundled with this book (tooltips-link-multi.html and data-link.csv). A working example can be found on bl.ocks.org.

Hopefully that helps people with a similar desire to include links in their tooltips. Many thanks to the reader who suggested it :-).

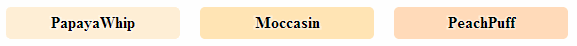

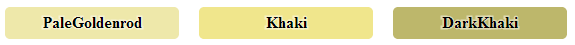

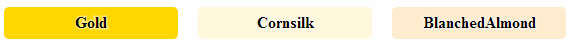

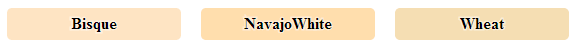

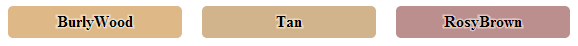

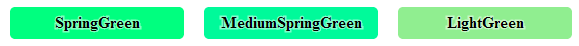

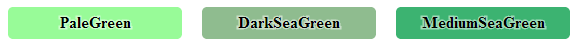

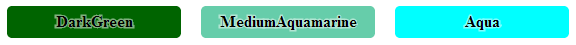

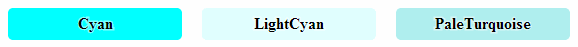

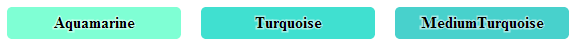

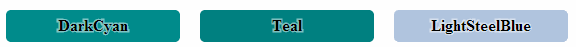

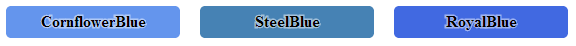

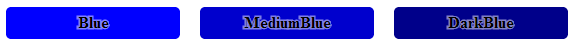

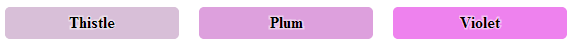

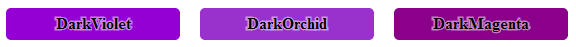

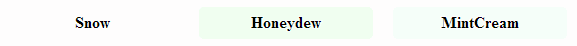

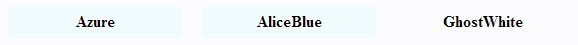

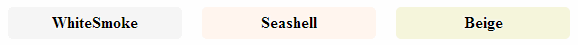

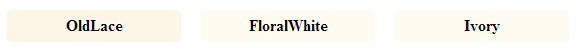

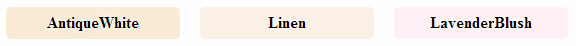

What are the predefined, named colours?

Throughout this document I generally use colours defined by name. This is mainly because I can, and not for any other reason. In fact there several different ways to define colours used in D3 / JavaScript / CSS and HTML. I have no idea what the limitations for use are and / or how their use in different browsers impacts on correct representation. But I do know that they’re used widely.

There seem to be several different standards for what constitutes an authoritative list of named colours. After a cursory search I was able to find a great list on about.com and there are some nice representations on Wikipedia.

The overriding point of all this is that there’s more than one way to define colours in your graphs.

It means that considering…

.style("fill", "steelblue")

and…

.style("fill", "#4682b4")

and…

.style("fill", "rgb(70,130,180)")

All three alternatives result in the same colour being applied.

For a long time I didn’t actually have the images of the colours represented here in D3 Tips and Tricks, but like all things, one day I thought ‘Hey, I could just write a simple script that placed them on the screen’. So here they are :-).

I have tried to group them as ‘like’ colours per the entry in Wikipedia.

You can also see a live page with the script that produces the rectangles at bl.ocks.org.

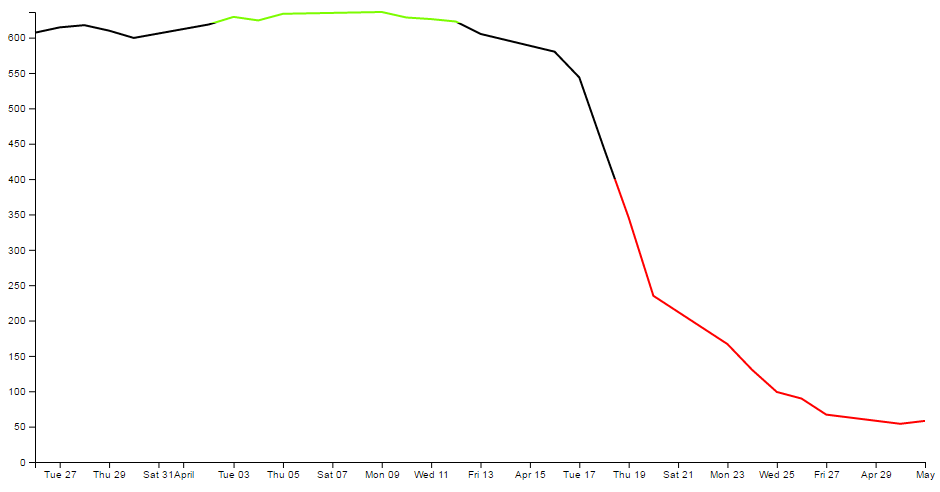

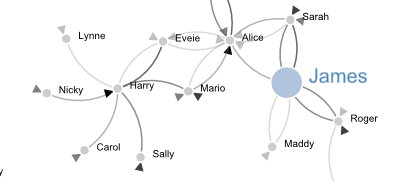

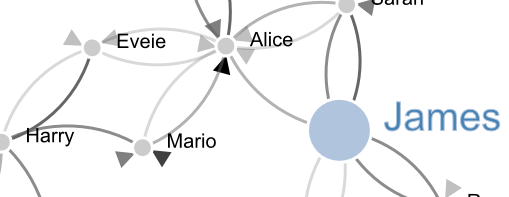

Selecting / filtering a subset of objects

Imagine a scenario where you want to select (or should we say filter) a particular range of objects from a larger set.

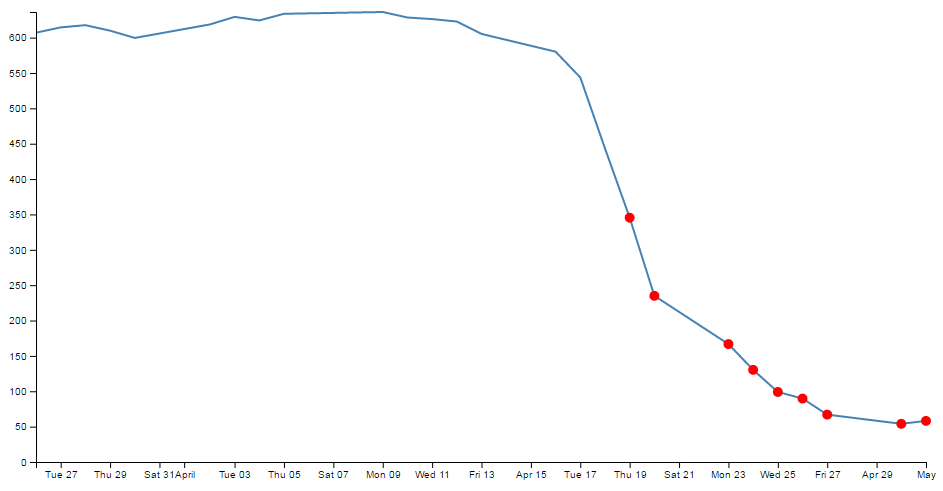

For example, what if we wanted to use our scatter plot example to show the line as normal, but we are particularly interested in the points where the values of the points fall below 400. Therefore, when the value falls below 400 we want them highlighted with a circle as we have done with *the scatter plot points previously.

So that we end up with something that looks a little like this…

Err… Yes, for those among you who are of the observant persuasion, I have deliberately coloured them red as well (red for DANGER!).

This is a fairly simple example, but serves to illustrate the principle adequately. From our simple scatter plot example we only need to add in two lines to the block of code that draws the circles as follows;

// Add the scatterplot

svg.selectAll("dot")

.data(data)

.enter().append("circle")

.filter(function(d) { return d.close < 400 }) // <== This line

.style("fill", "red") // <== and this one

.attr("r", 5)

.attr("cx", function(d) { return x(d.date); })

.attr("cy", function(d) { return y(d.close); });

The full code for this example can be found on github or in the code samples bundled with this book (filter-selection.html and data.csv). A working example can be found on bl.ocks.org.

The first added line uses the .filter function to act on the data points and according to the arguments passed to it in this case, only return those where the value of d.close is less than 400 (return d.close < 400).

The second added line simply colours the circles red (.style("fill", "red")).

That’s all there is to it. Pretty simple, but the filter function can be very powerful when used wisely.

Select items with an IF statement.

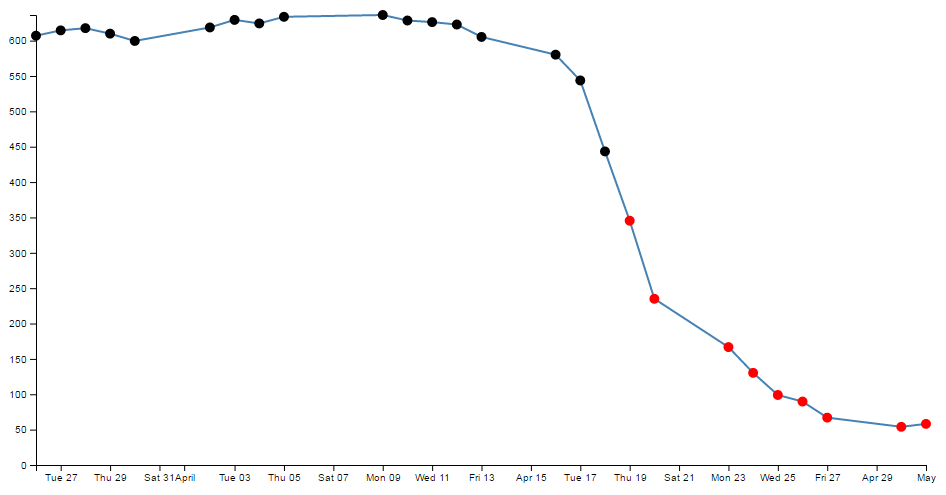

The filtering – selection section above is a good way to adapt what you see on a graph, but so is a more familiar friend… The ‘if’ statement.

An ‘if’ statement will act to carry out a task in a particular way dependant on a condition that you specify.

Starting with the simple scatter plot example all we have to do is include the if statement in the block of code that draws the circles. Here’s the entire block with the additions highlighted;

// Add the scatterplot

svg.selectAll("dot")

.data(data)

.enter().append("circle")

.attr("r", 5)

.style("fill", function(d) { // <== Add these

if (d.close <= 400) {return "red"} // <== Add these

else { return "black" } // <== Add these

;}) // <== Add these

.attr("cx", function(d) { return x(d.date); })

.attr("cy", function(d) { return y(d.close); });

Our first added line introduces the style modifier and the rest of the code acts to provide a return for the ‘fill’ attribute.

The second line introduces our if statement. There’s very little difference using if statements between languages. Just look out for maintaining the correct syntax and you should be fine. In this case we’re asking if the value of ‘d.close’ is less than or equal to 400 and if it is it will return the "red" statement for our fill.

The third line covers our rear and make sure that if the colour isn’t going to be red, it’s going to be black. The last line just closes the style and function statements.

The result?

Aww….. nice.

The full code for this example can be found on github or in the code samples bundled with this book (if-selection.html and data.csv). A working example can be found on bl.ocks.org.

Could it be any cooler? I’m glad you asked.

What if we wanted to have all the points where close was less than 400 red and all those where close was greater than 620 green? Oh yeah! Now we’re talking.

So with one small change to the if statement;

.style("fill", function(d) {

if (d.close <= 400) {return "red"}

else if (d.close >= 620) {return "lawngreen"} // <== Right here

else { return "black" }

;})

Check it out…

Nice.

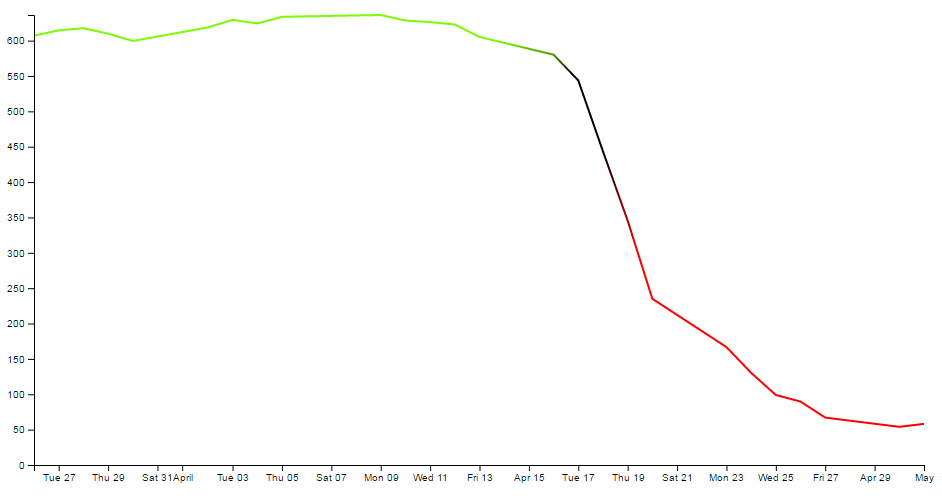

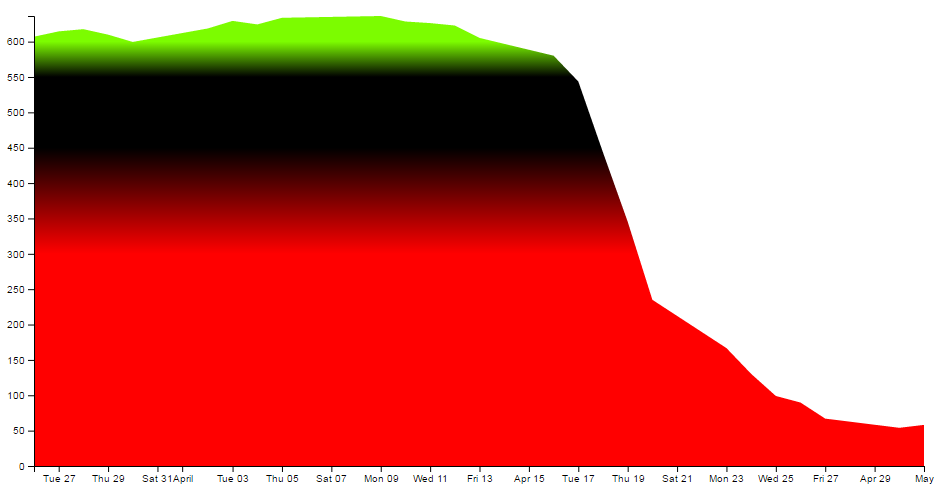

Applying a colour gradient to a line based on value.

I know that we were impressed with the changing dots in a scatter plot based on the value. But could we go one better?

How about we try to reproduce the same effect but by varying the colour of the plotted line. This is a neat feature and a useful example of the flexibility of d3.js and SVG in general. I used the appropriate bits of code from Mike Bostock’s Threshold Encoding example. And I should take the opportunity to heartily recommend browsing through his collection of examples on bl.ocks.org.

The full code for this example can be found on github or in the code samples bundled with this book (line-graph-gradient.html and data.csv). A working example can be found on bl.ocks.org.

Here then is a plotted line that is red below 400, green above 620 and black in between.

How cool is that?

Enough beating around the bush, how is the magic line produced?

Starting with our simple line graph, there are only two blocks of code to go in. One is CSS in the <style> area and the second is a tricky little piece of code that deals with gradients.

First the CSS.

.line {

fill: none;

stroke: url(#line-gradient);

stroke-width: 2px;

}

This block will go in the <style> area.

There’s the fairly standard fill of none and a stroke width of 2 pixels, but the stroke: url(#line-gradient); is something different.

In this case the stroke (the colour of the line) is being determined at a link within the page which is set by the anchor #line-gradient. We will see shortly that this is in our second block of code, so the colour is being defined in a separate portion of the script.

And now the JavaScript gradient code;

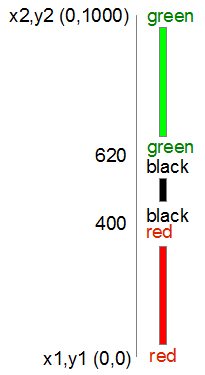

// set the gradient

svg.append("linearGradient")

.attr("id", "line-gradient")

.attr("gradientUnits", "userSpaceOnUse")

.attr("x1", 0).attr("y1", y(0))

.attr("x2", 0).attr("y2", y(1000))

.selectAll("stop")

.data([

{offset: "0%", color: "red"},

{offset: "40%", color: "red"},

{offset: "40%", color: "black"},

{offset: "62%", color: "black"},

{offset: "62%", color: "lawngreen"},

{offset: "100%", color: "lawngreen"}

])

.enter().append("stop")

.attr("offset", function(d) { return d.offset; })

.attr("stop-color", function(d) { return d.color; });

There’s our anchor on the third line!

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. This block should be placed after the x and y domains are set, but before the line is drawn.

Our second line adds our linear gradient. Gradients consist of continuously smooth colour transitions along a vector from one colour to another. We can have a linear or radial gradient and depending on which you select, there are a few options to define. There is some great information on gradients at http://www.w3.org/TR/SVG/pservers.html (more than I ever thought existed).

The third line (.attr("id", "line-gradient")) sets our anchor for the CSS that we saw earlier.

The fourth, fifth and sixth lines define the bounds of the area over which the gradient will act. Since the coordinates x1, y1, x2, y2 will describe an area. The values for y1 (0) and y2 (1000) are used more for convenience to align with our data (which has a maximum value around 630 or so). For more information on the ‘gradientUnits’ attribute I found this page useful https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/SVG/Attribute/gradientUnits. We’ll come back to the coordinates in a moment.

The next block selects all the ‘stop’ elements for the gradients. These stop elements define where on the range covered by our coordinates the colours start and stop. These have to be defined as either percentages or numbers (where the numbers are really just percentages in disguise (i.e. 45% =0.45)).

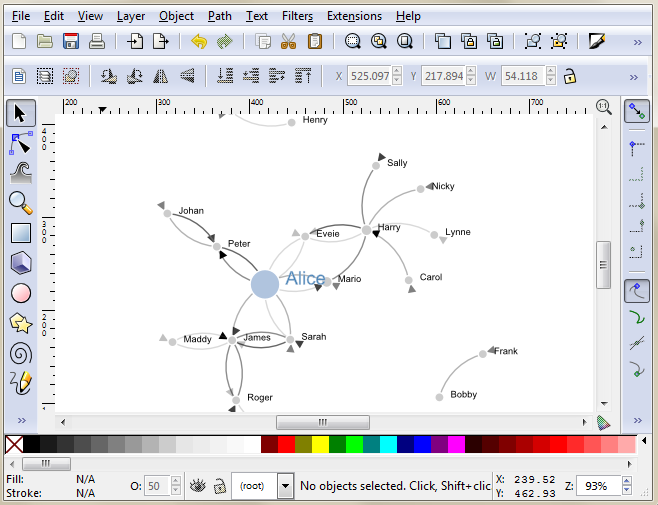

The best way to consider the stop elements is in conjunction with the gradientUnits. The image following may help.

In this case our coordinates describe a vertical line from 0 to 1000. Our colours transition from red (0) to red (400) at which point they change to black (400) and this will continue until it gets to black (620). Then this changes to green (620) and from there, any value above that will be green.

After defining the stop elements, we enter and append the elements to the gradient (.enter().append("stop")) with attributes for offset and colour that we defined in the stop elements area.

Now, that IS cool, but by now, I hope that you have picked that a gradient function really does mean a gradient, and not just a straight change from one colour to another.

So, let’s try changing the stop element offsets to the following (and making the stroke-width slightly larger to see more clearly what’s going on);

.data([

{offset: "0%", color: "red"},

{offset: "30%", color: "red"},

{offset: "45%", color: "black"},

{offset: "55%", color: "black"},

{offset: "60%", color: "lawngreen"},

{offset: "100%", color: "lawngreen"}

])

And here we go…

Ahh… A real gradient.

I have tended to find that I need to have a good think about how I set the offsets and bounds when doing this sort of thing since it can get quite complicated quite quickly :-)

Applying a colour gradient to an area fill.

The previous example of a varying gradient on a line is neat, but hopefully you’re already thinking “Hang on, can’t that same thing be applied to an area fill?”.

Damn! You’re catching on.

To do this there’s only a few things we need to change;

First of all the CSS for the line needs to be amended to refer to the area. So this…

.line {

fill: none;

stroke: url(#line-gradient);

stroke-width: 2px;

}

…gets changed to this…

.area {

fill: url(#area-gradient);

stroke-width: 0px;

}

We’ve defined the styles for the area this time, but instead of the stroke being defined by the separate script, now it’s the area. While we’ve changed the url name, it’s actually the same piece of code, with a different id (because it seemed wrong to be talking about an area when the label said line). We’ve also set the stroke width to zero, because we don’t want any lines around our filled area.

Now we want to take the block of code that defined our line…

// define the line

var valueline = d3.line()

.x(function(d) { return x(d.date); })

.y(function(d) { return y(d.close); });

… and we need to replace it with the standard block that defined an area fill.

// define the area

var area = d3.area()

.x(function(d) { return x(d.date); })

.y0(height)

.y1(function(d) { return y(d.close); });

So we’re not going to be drawing a line at all. Just the area fill.

Next, as I mentioned earlier, we change the id for the linearGradient block from "line-gradient" to "area-gradient"

.attr("id", "area-gradient")

And lastly, we remove the block of code that drew the line and replace it with a block that draws an area. So change this….

// Add the valueline path.

svg.append("path")

.data([data])

.attr("class", "line")

.attr("d", valueline);

… to this;

// Add the area.

svg.append("path")

.data([data])

.attr("class", "area")

.attr("d", area);

And then sit back and marvel at your creation;

The full code for this example can be found on github or in the code samples bundled with this book (area-graph-gradient.html and data.csv). A working example can be found on bl.ocks.org.

For a slightly ‘nicer’ looking example, you could check out a variation of one of Mike Bostock’s (v3) originals here; http://bl.ocks.org/4433087.

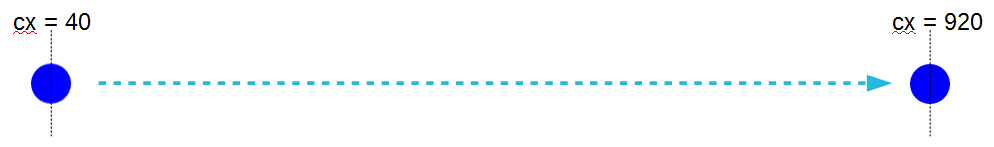

Transitions

A transition in d3 is an application of an animation to an element on the page. For the purposes of demonstration we can think of an element being one of the common shapes and objects which include circles, ellipses, rectangles, lines, polylines, polygons, text and paths. This is a gross oversimplification as transitions can be applied in far more complex ways, but this will help us get started. An animation could be described as a change in an attribute or style of an element over time

If we use a circle as an example we know that a circle is described by three required attributes;

-

cx: The position of the centre of the circle in the x direction (left / right) measured from the left side of the screen. -

cy: The position of the centre of the circle in the y direction (up / down) measured from the top of the screen. -

r: The radius of the circle from thecx,cyposition to the perimeter of the circle.

To animate a circle we would therefore be changing (or transitioning) one of those attributes over time.

The following JavaScript will draw a simple blue circle with radius 20 pixels at the position 40,250

var svg = d3.select("body") // Select the body element

.append("svg") // Append an SVG element to the body

.attr("width", 960) // make it 960 pixels wide

.attr("height", 500) // make it 500 pixels high

.append("circle") // append a cicle to the svg

.attr("style", "blue") // fill the circle with 'blue'

.attr("r", 20) // set the radius to 10 pixels

.attr('cx', 40) // position the circle at 40 on the x axis

.attr('cy', 250); // position the circle at 250 on the y axis

To transition that circle from left to right we would change the cx attribute by simply including the transition instruction the new value of the attribute to be changed and the time that it should be completed in;

.transition() // apply a transition

.duration(4000) // apply it over 4000 milliseconds

.attr('cx', 920); // new horizontal position at 920 on x axis

The total amount of code required is;

<!DOCTYPE html>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<body>

<!-- load the d3.js library -->

<script src="https://d3js.org/d3.v4.min.js"></script>

<script>

var svg = d3.select("body") // Select the body element

.append("svg") // Append an SVG element to the body

.attr("width", 960) // make it 960 pixels wide

.attr("height", 500) // make it 500 pixels high

.append("circle") // append a circle to the svg

.attr("style", "blue") // fill the circle with 'blue'

.attr("r", 20) // set the radius to 10 pixels

.attr('cx', 40) // position the circle at 40 on the x axis

.attr('cy', 250) // position the circle at 250 on the y axis

.transition() // apply a transition

.duration(4000) // apply it over 4000 milliseconds

.attr('cx', 920); // new horizontal position at 920 on x axis

</script>

</body>

And seen on the web page our circle moves from left to right.

A transition can be of more than one attribute at the same time. If we add lines to change the radius and fill colour as well we will have some JavaScript that looks a bit like this;

var svg = d3.select("body") // Select the body element

.append("svg") // Append an SVG element to the body

.attr("width", 960) // make it 960 pixels wide

.attr("height", 500) // make it 500 pixels high

.append("circle") // append a circle to the svg

.style("fill", "blue") // fill the circle with 'blue'

.attr("r", 20) // set the radius to 10 pixels

.attr('cx', 40) // position the circle at 40 on the x axis

.attr('cy', 250) // position the circle at 250 on the y axis

.transition() // apply a transition

.duration(4000) // apply it over 4000 milliseconds

.attr('cx', 920) // new horizontal position at 920 on x axis

.attr('r', 40) // new radius of 40 pixels

.style('fill', "red"); // new colour red

And when we load the page we see our circle move from left to right wile at the same time increasing in radius and changing colour from blue to red.

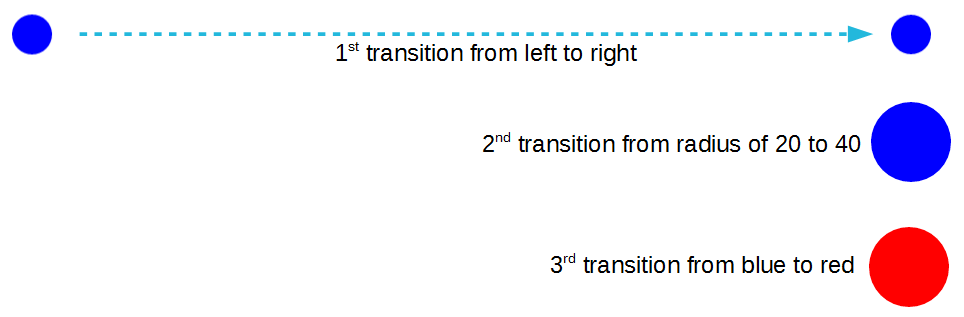

Transitioning Chaining

Instead of having multiple attributes / styles changing at once we can stagger them using transition chaining. This is where we can employ several different transitions to an element one after the other.

For example, the following JavaScript will move our circle from left to right then it will increase the radius from 20 to 40 and then it will change it’s colour from blue to red.

var svg = d3.select("body") // Select the body element

.append("svg") // Append an SVG element to the body

.attr("width", 960) // make it 960 pixels wide

.attr("height", 500) // make it 500 pixels high

.append("circle") // append a circle to the svg

.style("fill", "blue") // fill the circle with 'blue'

.attr("r", 20) // set the radius to 10 pixels

.attr('cx', 40) // position the circle at 40 on the x axis

.attr('cy', 250) // position the circle at 250 on the y axis

// 1st transition

.transition() // apply a transition

.duration(4000) // apply it over 4000 milliseconds

.attr('cx', 920) // new horizontal position at 920 on x axis

// 2nd transition

.transition() // apply a transition

.duration(4000) // apply it over 4000 milliseconds

.attr('r', 40) // new radius of 40 pixels

// 3rd transition

.transition() // apply a transition

.duration(4000) // apply it over 4000 milliseconds

.style('fill', "red"); // new colour red

Transition Easing

The reader who runs the code or checks out the simple example here will notice that our circle does not move from one side to the other at a constant speed. It starts off slowly, builds up speed towards the middle of its travels and then slows down before stopping. This gives the movement a pleasing appearance, but it is an example of the ‘easing’ of the transition from one point to another.

To apply a linear motion to the movement we can introduce .ease(d3.easeLinear) to the code as follows;

var svg = d3.select("body") // Select the body element

.append("svg") // Append an SVG element to the body

.attr("width", 960) // make it 960 pixels wide

.attr("height", 500) // make it 500 pixels high

.append("circle") // append a circle to the svg

.style("fill", "blue") // fill the circle with 'blue'

.attr("r", 20) // set the radius to 10 pixels

.attr('cx', 40) // position the circle at 40 on the x axis

.attr('cy', 250) // position the circle at 250 on the y axis

.transition() // apply a transition

.ease(d3.easeLinear) // control the speed of the transition

.duration(4000) // apply it over 4000 milliseconds

.attr('cx', 920); // new horizontal position at 920 on x axis

The easing of an element describes a distortion in the apparent flow of time. There are a range of different types of easing described in the d3 wiki. Most are representative of a function although there are some which are intended to represent specific real-world motions.

- linear

- quad

- cubic

- poly

- sin

- exp

- circle

- bounce

- back

- elastic

Each easing (except linear) can be further modified using ‘In’, ‘Out’ or InOut’ which allows for variations in the animation that can give the appearance of starting or stopping at different points in the curves or in the case of ‘InOut’ of going through a complete transition. For example, .ease(d3.easeExpIn) or .ease(d3.easePolyInOut).

If an easing function is not specified, the default used is cubic and if ‘In’, ‘Out’ or InOut’ aren’t specified, the default is ‘InOut’ except for bounce and elastic which use ‘Out’. Therefore we can use .ease(d3.easePoly) which is an alias for .ease(d3.easePolyInOut). ‘easePoly’ is also an alias for ‘easeCubic’ (and vice versa).

To get a good impression of the way that each easing method is represented, Mike Bostock has an ‘Easing Explorer’ block set up here. There is also a block to do a side by side comparison here (this is also in the code samples bundled with this book (transition-easing-multiple.html)).

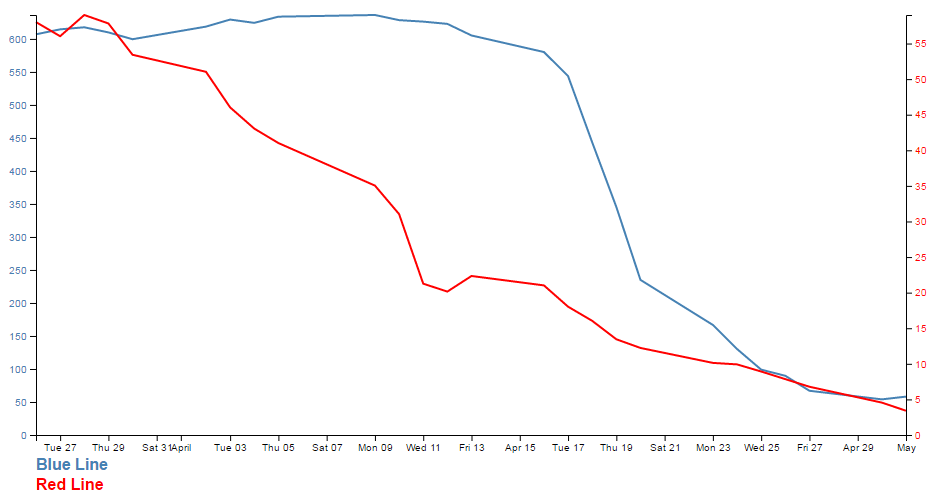

Show / hide an element by clicking on another element

This is a trick that I found I wanted to implement in order to present a graph with a range of lines and to then provide the reader with the facility to click on the associated legend to toggle the visibility of the lines off and on as required.

The example we’ll follow is our friend from earlier, a slightly modified example of the graph with two lines.

In this example we will be able to click on either of the two titles at the bottom of the graph (‘Blue Line’ or ‘Red Line’) and have it toggle the respective line and Y axis.

The code

The code for the example is available online at bl.ocks.org or GitHub. It is also available as the file ‘show-hide.html’ that can be a download when you download the book from Leanpub.

There are more changes in the example code than we will explain below such as the addition of CSS to the <style> area and the code that allows both of the lines to be shown / hidden (we’ll only go through the blue line code).

There are two main parts to implementing this technique. Firstly we have to label the element (or elements) that we wish to show / hide and then we have to give the object that will get clicked on the attribute that allows it to recognise a mouse click and the code that it subsequently uses to show / hide our labelled element.

Labelling the element that is to be switched on and off is dreadfully easy. It simply involves including an id attribute to an element that identifies it uniquely.

// add the valueline path.

svg.append("path")

.data([data])

.attr("class", "line")

.attr("id", "blueLine")

.attr("d", valueline);

In the example above we have applied the id blueLine to the path that draws the blue line on our graph.

The second part is a little trickier. The following is the portion of JavaScript that places our text label under the graph. The only part of it that is unusual is the .on("click", function() section of the code.

// add the blue line legend

svg.append("text")

.attr("x", 0)

.attr("y", height + margin.top + 15)

.attr("class", "legend")

.style("fill", "steelblue")

.on("click", function(){

// determine if current line is visible

var active = blueLine.active ? false : true,

newOpacity = active ? 0 : 1;

// hide or show the elements

d3.select("#blueLine").style("opacity", newOpacity);

// update whether or not the elements are active

blueLine.active = active;

})

.text("Blue Line");

When we click on our ‘Blue Line’ text element the .on("click", function() section executes.

We’re using a short-hand version of the if statement a couple of times here. Firstly we check to see if the variable blueLine.active is true or false and if it’s true it gets set to false and if it’s false it gets set to true (not at all confusing).

var active = blueLine.active ? false : true,

newOpacity = active ? 0 : 1;

Then after toggling this variable we set the value of newOpacity to either 0 or 1 depending on whether active is false or true (the second short-hand JavaScript if statement).

We can then select our identifiers that we have declared using the id attributes in the earlier pieces of code and modify their opacity to either 0 (off) or 1 (on)

d3.select("#blueLine").style("opacity", newOpacity);

Lastly we update our blueLine.active variable to whatever the active state is so that it can toggle correctly the next time it is clicked on.

blueLine.active = active;

Quite a neat piece of code. Kudos to Max Leiserson for providing the example on which it is largely based in an answer to a question on Stack Overflow.

Using HTML inputs with d3.js

Part of the attraction of using technologies like d3.js is that it expands the scope of what is possible in a web page. At the same time, there are many different options for displaying content on a page and plenty of ways of interacting with it.

Some of the most basic of capabilities has been the use of HTML entities that allow the entry of data on a page. This can take a range of different forms (pun intended) and the <input> tag is one of the most basic.

What is an HTML input?

An HTML input is an element in HTML that allows a web page to input data. There are a range of different input types (with varying degrees of compatibility with browsers) and they are typically utilised inside a <form> element.

For example the following code allows a web page to place two fields on a web page so that a user can enter their first and last names in separate boxes;

<form>

First name: <input type="text" name="firstname"><br>

Last name: <input type="text" name="lastname">

</form>

The page would then display the following;

The range of input types is large and includes;

- text: A simple text field that a user can enter information into.

- radio: Buttons that let a user select only one of a limited number of choices.

- button: A clickable button that can activate JavaScript.

- range: A slider control for setting a number whose exact value is not important.

- number: A field for entering a number or toggling a number up and down.

… and many more. To check out others and get further background, it would be worthwhile visiting the Mozilla developer pages or w3schools.com.

While d3.js has the power to control and manipulate a web page to an extreme extent, sometimes it’s desirable to use a simple process to get a result. The following explanations will demonstrate a simple use case linking an HTML input with a d3.js element and will go on to provide examples of using multiple inputs, affecting multiple elements and using different input types. The examples are deliberately kept simple. They are intended to demonstrate functionality and to provide a starting position for you to go forward :-).

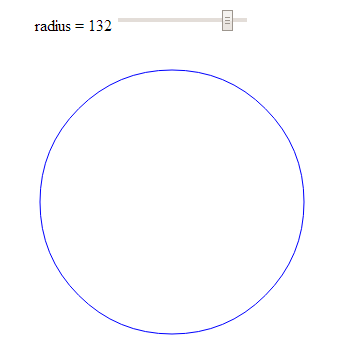

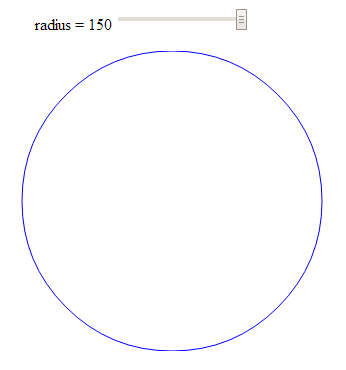

Using a range input with d3.js

The first example we will follow will use a range input to adjust the radius of a circle.

The code

The following is the full code for the example. A live version is available online at bl.ocks.org or GitHub. It is also available as the file ‘input-radius.html’ as a separate download with the book D3 Tips and Tricks v4.x. A copy of the files that appear in the book can be downloaded (in a zip file) when you download the book from Leanpub.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Input test (circle)</title>

<p>

<label for="nRadius"

style="display: inline-block; width: 240px; text-align: right">

radius = <span id="nRadius-value">…</span>

</label>

<input type="range" min="1" max="150" id="nRadius">

</p>

<script src="https://d3js.org/d3.v4.min.js"></script>

<script>

var width = 600;

var height = 300;

var holder = d3.select("body")

.append("svg")

.attr("width", width)

.attr("height", height);

// draw the circle

holder.append("circle")

.attr("cx", 300)

.attr("cy", 150)

.style("fill", "none")

.style("stroke", "blue")

.attr("r", 120);

// when the input range changes update the circle

d3.select("#nRadius").on("input", function() {

update(+this.value);

});

// Initial starting radius of the circle

update(120);

// update the elements

function update(nRadius) {

// adjust the text on the range slider

d3.select("#nRadius-value").text(nRadius);

d3.select("#nRadius").property("value", nRadius);

// update the circle radius

holder.selectAll("circle")

.attr("r", nRadius);

}

</script>

The explanation

As with the other examples in the book I will not go over some of the simpler lines of code that are covered in greater detail in earlier sections of the book and will concentrate on those sections that contain new concepts, code or look like they might need expanding :-).

The first section is the portion that sets out the html range input;

<p>

<label for="nRadius"

style="display: inline-block; width: 240px; text-align: right">

radius = <span id="nRadius-value">…</span>

</label>

<input type="range" min="1" max="150" id="nRadius">

</p>

The entire block is enclosed in a paragraph (<p>) tag so that is appears on a single line. It can be broken down into the label that occurs before the input slider which is given the id nRadius-value and the input proper.

The for attribute of the label tag equals to the id attribute of the input element to bind them together. This allows us to update the text later as the slider is moved.

The input tag can include four attributes that specify restrictions on the operation of the slider;

-

max: specifies the maximum value allowed -

min: specifies the minimum value allowed -

step: specifies the number intervals as you move the slider -

value: Specifies the default value

The ids supplied for both the label and the input are important since they provide the reference for our d3.js script.

The first portion of our JavaScript is fairly routine if you’ve been following along with the rest of the book.

var width = 600;

var height = 300;

var holder = d3.select("body")

.append("svg")

.attr("width", width)

.attr("height", height);

// draw the circle

holder.append("circle")

.attr("cx", 300)

.attr("cy", 150)

.style("fill", "none")

.style("stroke", "blue")

.attr("r", 120);

We append an SVG element to the body of our page and then we append a circle with some particular styling to the SVG element.

Then things start to get more interesting…

d3.select("#nRadius").on("input", function() {

update(+this.value);

});

We select our input using the id that we had declared earlier in the html (nRadius). Then we use the .on operator which adds what is called an ‘event listener’ to the element so that when there is a change in the element (in this case an adjustment of the slider of the input) a function is called (function()) that in turn calls the update function with the value from the input (+this.value). We haven’t seen the update function yet, but never fear, it’s coming.

We also call the update function with a specific value in the next line;

update(120);

This might seem slightly redundant, but unless the function gets a value, the text associated with the range input doesn’t get a reading and remains on ‘…’ until the slider is moved.

Lastly we have our update function;

function update(nRadius) {

// adjust the text on the range slider

d3.select("#nRadius-value").text(nRadius);

d3.select("#nRadius").property("value", nRadius);

// update the circle radius

holder.selectAll("circle")

.attr("r", nRadius);

}

The first part of the function selects the label associated with our input (with the id, nRadius-value) and applies the value that has been passed into the function (nRadius). The next line selects the input itself and applies the value to it (this would be the equivalent of having value="<number here>" as a property in the html).

Lastly, we select the circle element and apply the new radius value based on our input value nRadius (.attr("r", nRadius)).

And there we have it, a fully adjustable radius for our circle controlled with an HTML input.

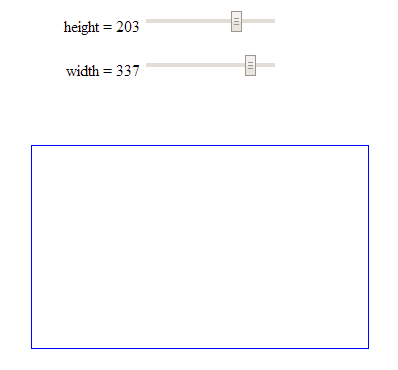

Using more than one input

In this example we will use two separate inputs (range type) to adjust the height and width of a rectangle.

This is not too much of a stretch from the previous single input example with the radius of a circle, but it may be useful to reinforce the concept and illustrate something slightly different.

The code

The following is the full code for the example. A live version is available online at bl.ocks.org or GitHub. It is also available as the file ‘input-double.html’ as a separate download with D3 Tips and Tricks v4.x. A copy of the files that appear in the book can be downloaded (in a zip file) when you download the book from Leanpub.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Double Input Test</title>

<p>

<label for="nHeight"

style="display: inline-block; width: 240px; text-align: right">

height = <span id="nHeight-value">…</span>

</label>

<input type="range" min="1" max="280" id="nHeight">

</p>

<p>

<label for="nWidth"

style="display: inline-block; width: 240px; text-align: right">

width = <span id="nWidth-value">…</span>

</label>

<input type="range" min="1" max="400" id="nWidth">

</p>

<script src="https://d3js.org/d3.v4.min.js"></script>

<script>

var width = 600;

var height = 300;

var holder = d3.select("body")

.append("svg")

.attr("width", width)

.attr("height", height);

// draw a rectangle

holder.append("rect")

.attr("x", 300)

.attr("y", 150)

.style("fill", "none")

.style("stroke", "blue")

.attr("height", 150)

.attr("width", 200);

// read a change in the height input

d3.select("#nHeight").on("input", function() {

updateHeight(+this.value);

});

// read a change in the width input

d3.select("#nWidth").on("input", function() {

updateWidth(+this.value);

});

// update the values

updateHeight(150);

updateWidth(100);

// Update the height attributes

function updateHeight(nHeight) {

// adjust the text on the range slider

d3.select("#nHeight-value").text(nHeight);

d3.select("#nHeight").property("value", nHeight);

// update the rectangle height

holder.selectAll("rect")

.attr("y", 150-(nHeight/2))

.attr("height", nHeight);

}

// Update the width attributes

function updateWidth(nWidth) {

// adjust the text on the range slider

d3.select("#nWidth-value").text(nWidth);

d3.select("#nWidth").property("value", nWidth);

// update the rectangle width

holder.selectAll("rect")

.attr("x", 300-(nWidth/2))

.attr("width", nWidth);

}

</script>

The explanation

For the sake of brevity, this explanation will simply concentrate on the differences between the previous single input example and this one.

The declarations for the inputs in the HTML at the start of the code are simply duplicates of each other in terms of function;

<p>

<label for="nHeight"

style="display: inline-block; width: 240px; text-align: right">

height = <span id="nHeight-value">…</span>

</label>

<input type="range" min="1" max="280" id="nHeight">

</p>

<p>

<label for="nWidth"

style="display: inline-block; width: 240px; text-align: right">

width = <span id="nWidth-value">…</span>

</label>

<input type="range" min="1" max="400" id="nWidth">

</p>

The only significant difference is the declaration of the id’s for each input and their respective labels.

The JavaScript selection of the inputs is more duplication;

d3.select("#nHeight").on("input", function() {

updateHeight(+this.value);

});

d3.select("#nWidth").on("input", function() {

updateWidth(+this.value);

});

Again the only substantive difference is the use of the appropriate id values.

The updating of the width and height is done via two different functions;

function updateHeight(nHeight) {

// adjust the text on the range slider

d3.select("#nHeight-value").text(nHeight);

d3.select("#nHeight").property("value", nHeight);

// update the rectangle height

holder.selectAll("rect")

.attr("y", 150-(nHeight/2))

.attr("height", nHeight);

}

// Update the width attributes

function updateWidth(nWidth) {

// adjust the text on the range slider

d3.select("#nWidth-value").text(nWidth);

d3.select("#nWidth").property("value", nWidth);

// update the rectangle width

holder.selectAll("rect")

.attr("x", 300-(nWidth/2))

.attr("width", nWidth);

}

The rectangle is selected using a common rect designator, so multiple rectangles could be controlled. But each function controls only a specific attribute (height or width).

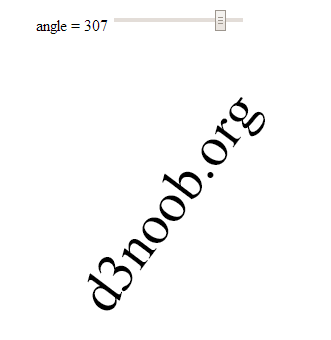

Rotate text with an input

This example is really just a derivative of the adjustment of a single attribute of an element.

I happen to think it’s just a little bit ‘neater’ because it includes text, but in reality, it’s just another attribute that can be adjusted.

Here we let our range input adjust the rotation of a piece of text.

The explanation

We’ll dispense with the full code listing since it’s just a regurgitation of the adjusting of the radius of the circle example, but the code for the example is available online at bl.ocks.org or GitHub. It is also available as the file ‘input-text-rotate.html’ as a separate download with D3 Tips and Tricks v4.x. A copy of the files that appear in the book can be downloaded (in a zip file) when you download the book from Leanpub.

The only, thing of even a slight difference (other than some naming conventions) is the initial drawing of the text…

holder.append("text")

.style("fill", "black")

.style("font-size", "56px")

.attr("dy", ".35em")

.attr("text-anchor", "middle")

.attr("transform", "translate(300,150) rotate(0)")

.text("d3noob.org");

… and the update function;

function update(nAngle) {

// adjust the text on the range slider

d3.select("#nAngle-value").text(nAngle);

d3.select("#nAngle").property("value", nAngle);

// rotate the text

holder.select("text")

.attr("transform", "translate(300,150) rotate("+nAngle+")");

}

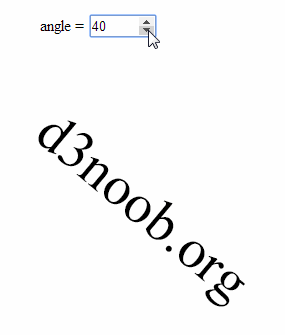

Use a number input with d3.js

There are obviously different inputs types that can be implemented. The following example still rotates our text, but uses a number type of input to do it;

<p>

<label for="nValue"

style="display: inline-block; width: 240px; text-align: right">

angle = <span id="nValue-value"></span>

</label>

<input type="number" min="0" max="360" step="5" value="0" id="nValue">

</p>

We have set the step value to speed things up a bit when rotating, but it’s completely optional.

The input itself can be adjusted up or down using a mouse click or have a number typed into the input box.

This type of input is slightly different from the range type since it isn’t fully supported under Firefox and as a result when I was testing it the arrow keys for going up and down weren’t present.

The full code for the example is available online at bl.ocks.org or GitHub. It is also available as the file ‘input-number-text.html’ as a separate download with D3 Tips and Tricks v4.x. A copy of the files that appear in the book can be downloaded (in a zip file) when you download the book from Leanpub.

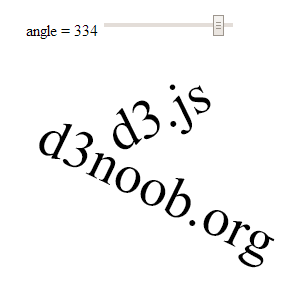

Change more than one element with an input

The final example looking at using HTML inputs with d3.js incorporates a single input acting or two different elements. This might seem self evident, but if you’re as unfamiliar with HTML as I am (it’s embarrassing I know, but what can you do?) it may be of assistance.

The end result is to produce a single slider as a range input that rotates two separate text objects in different directions simultaneously.

The code

The following is the full code for the example. A live version is available online at bl.ocks.org or GitHub. It is also available as the file ‘input-text-rotate-2.html’ as a separate download with D3 Tips and Tricks v4.x. A copy of the files that appear in the book can be downloaded (in a zip file) when you download the book from Leanpub.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Input test</title>

<p>

<label for="nAngle"

style="display: inline-block; width: 240px; text-align: right">

angle = <span id="nAngle-value">…</span>

</label>

<input type="range" min="0" max="360" id="nAngle">

</p>

<script src="https://d3js.org/d3.v4.min.js"></script>

<script>

var width = 600;

var height = 300;

var holder = d3.select("body")

.append("svg")

.attr("width", width)

.attr("height", height);

// draw d3.js text

holder.append("text")

.attr("class", "d3js")

.style("fill", "black")

.style("font-size", "56px")

.attr("dy", ".35em")

.attr("text-anchor", "middle")

.attr("transform", "translate(300,55) rotate(0)")

.text("d3.js");

// draw d3noob.org text

holder.append("text")

.attr("class", "d3noob")

.style("fill", "black")

.style("font-size", "56px")

.attr("dy", ".35em")

.attr("text-anchor", "middle")

.attr("transform", "translate(300,130) rotate(0)")

.text("d3noob.org");

// when the input range changes update the rectangle

d3.select("#nAngle").on("input", function() {

update(+this.value);

});

// Initial starting height of the rectangle

update(0);

// update the elements

function update(nAngle) {

// adjust the range text

d3.select("#nAngle-value").text(nAngle);

d3.select("#nAngle").property("value", nAngle);

// adjust d3.js text

holder.select("text.d3js")

.attr("transform", "translate(300,55) rotate("+nAngle+")");

// adjust d3noob.org text

holder.select("text.d3noob")

.attr("transform", "translate(300,130) rotate("+(360 - nAngle)+")");

}

</script>

The explanation

The explanation for this example differs from the others in the way that the d3.js elements (the two pieces of text) are initially appended and then updated.

When they are initially drawn…

holder.append("text")

.attr("class", "d3js")

.style("fill", "black")

.style("font-size", "56px")

.attr("dy", ".35em")

.attr("text-anchor", "middle")

.attr("transform", "translate(300,55) rotate(0)")

.text("d3.js");

holder.append("text")

.attr("class", "d3noob")

.style("fill", "black")

.style("font-size", "56px")

.attr("dy", ".35em")

.attr("text-anchor", "middle")

.attr("transform", "translate(300,130) rotate(0)")

.text("d3noob.org");

… both elements are declared with a class attribute that serves as a reference for the future updating. Here, the text ‘d3.js’ is given a class name of d3js and the text ‘d3noob.org’ is given a class name of d3noob.

Then when we call the update function each of the two text elements is adjusted seperatly by selecting each based on the class name that was applied in the initial setup;

function update(nAngle) {

// adjust the range text

d3.select("#nAngle-value").text(nAngle);

d3.select("#nAngle").property("value", nAngle);

// adjust d3.js text

holder.select("text.d3js")

.attr("transform", "translate(300,55) rotate("+nAngle+")");

// adjust d3noob.org text

holder.select("text.d3noob")

.attr("transform", "translate(300,130) rotate("+(360 - nAngle)+")");

}

So the ‘d3.js’ text is selected using text.d3js and ‘d3noob.org’ is selected using text.d3noob. That’s a pretty neat trick and a good lesson for applying specific transformations to specific objects.

Add an HTML table to your graph

So graphs and graphics are D3’s bread and butter you’d think. Hmm…

Well yes and no.

Yes D3 has extraordinary powers for presenting and manipulating images in a web page. But if you’ve read through the entirety of the d3.js main site (haven’t we all) you will recall that D3 actually stands for Data Driven Documents. It’s not necessarily about the pretty pictures and the swirling cascade of colour. It’s about generating something in a web browser based on data.

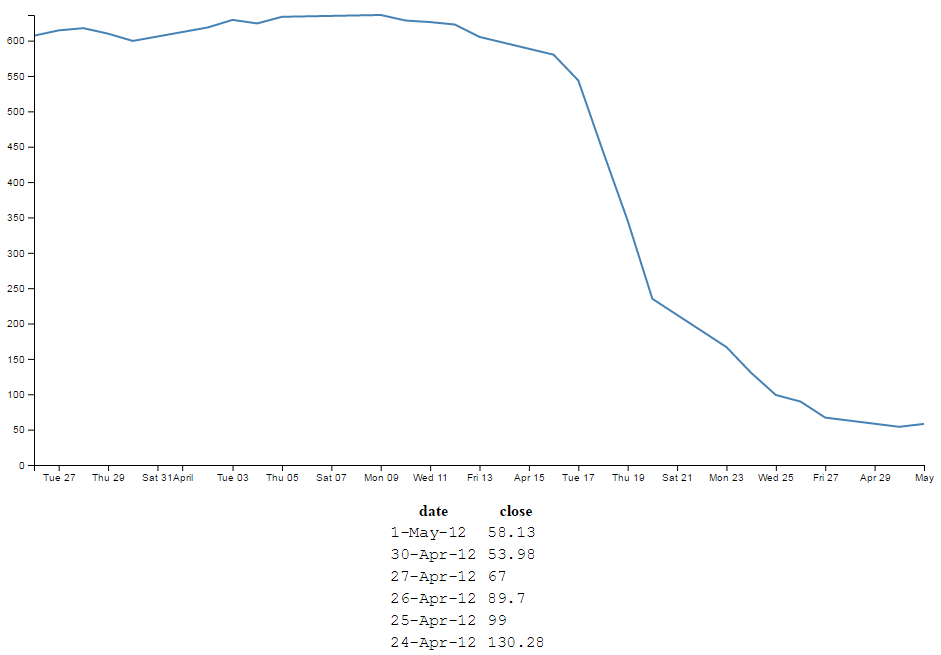

This transitions nicely into consideration of adding a table of information that can accompany your graph (it could just as easily (or easier) be stand alone, but for the sake of continuity, we’ll use the graph).

What we’ll do is add the data that we’ve used to make our simple graph under the graph itself. To make sure that it’s all nicely aligned, we’ll place it in a table.

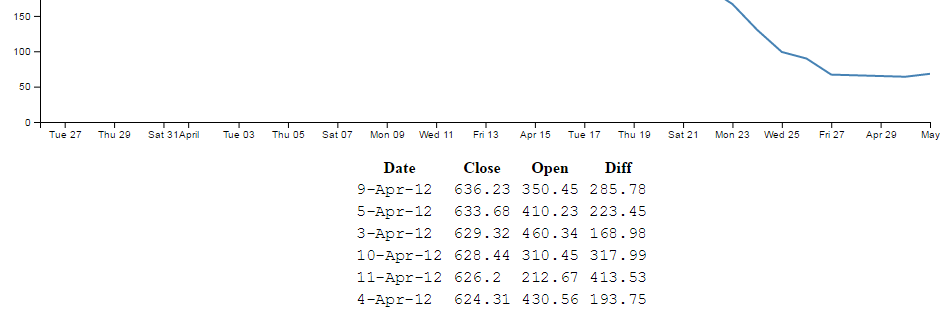

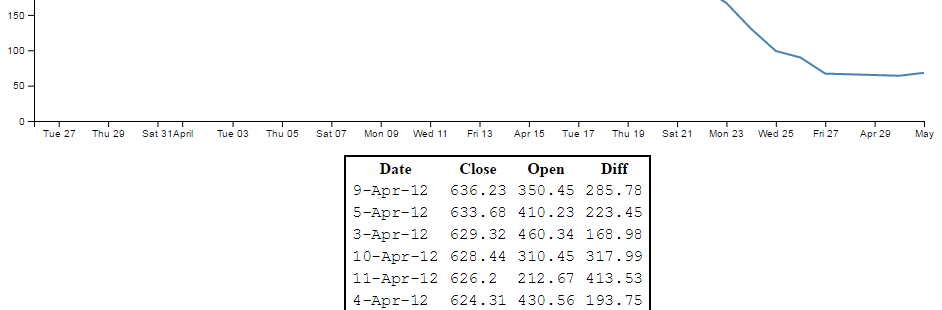

It should end up looking a little like this (and this has been cropped slightly at the bottom to avoid expanding the page with rows of numbers / dates).

The code was drawn from an example provided by Shawn Allen on Google Groups. In fact, the post itself is an excellent one if you are considering creating a table straight from a csv file.

HTML Tables

Tables are made up of rows, columns and data (that goes in each cell). All you need to do to successfully place a table on a web page is to lay out the rows and columns in a logical sequence using the appropriate HTML tags and you’re away.

For example here’s the total HTML code for a web page to display a simple table;

<!DOCTYPE html>

<body>

<table border="1">

<tr>

<th>Header 1</th>

<th>Header 2</th>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>row 1, cell 1</td>

<td>row 1, cell 2</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>row 2, cell 1</td>

<td>row 2, cell 2</td>

</tr>

</table>

</body>

This will result in a table that looks a little like this in a web browser;

| Header 1 | Header 2 |

| row 1, cell 1 | row 1, cell 2 |

| row 2, cell 1 | row 2, cell 2 |

The entire table itself is enclosed in <table> tags. Each row is enclosed in <tr> tags. Each row has two items which equate to the two columns. Each piece of data for each cell is enclosed in a <td> tag except for the first row, which is a header and therefore has a special tag <th> that denotes it as a header making it bold and centred. For the sake of ease of viewing we have told the table to place a border around each cell and we do this in the first <table> tag with the border="1" statement (although in this book view it may be absent).

There are three main things you need to do to the basic line graph to get your table to display.

- Add some CSS

- Add some table building d3.js code

- Make a small but cunning change…

There is a copy of the code and the data file for this example at github and in the code samples bundled with this book (simple-graph-plus-table.html and data.csv). A live example can be found on bl.ocks.org.

First the CSS

This just helps the table with formatting and making sure the individual cells are spaced appropriately;

td, th {

padding: 1px 4px;

}

This sets a padding of 1 px around each cell and 4 px between each column.

I’ve placed this portion of CSS at the end of our <style> section.

Now the d3.js code

Oki doki… Hopefully you have a loose understanding of the html layout of a table as explained above, but if not you can always go with the ‘it just works’ approach.

Here’s what we should add into our simple graph example;

// The table generation function

function tabulate(data, columns) {

var table = d3.select("body").append("table")

.attr("style", "margin-left: 400px"),

thead = table.append("thead"),

tbody = table.append("tbody");

// append the header row

thead.append("tr")

.selectAll("th")

.data(columns)

.enter()

.append("th")

.text(function(column) { return column; });

// create a row for each object in the data

var rows = tbody.selectAll("tr")

.data(data)

.enter()

.append("tr");

// create a cell in each row for each column

var cells = rows.selectAll("td")

.data(function(row) {

return columns.map(function(column) {

return {column: column, value: row[column]};

});

})

.enter()

.append("td")

.attr("style", "font-family: Courier") // sets the font style

.html(function(d) { return d.value; });

return table;

}

// render the table

var peopleTable = tabulate(data, ["date", "close"]);

And we should take care to add it into the code at the end of the portion where we’ve finished drawing the graph, but before the enclosing curly and regular brackets that complete the portion of the graph that has loaded our data.csv file. This is because we want our new piece of code to have access to that data and if we place it after those brackets it won’t know what data to display.

So, right about here;

// Add the Y Axis

svg.append("g")

.attr("class", "y axis")

.call(yAxis);

// <= Add the code right here!

});

Now, we’re going to break with tradition a bit here and examine what our current state of code produces. Then we’re going to explain something different. THEN we’re going to come back and explain the code…

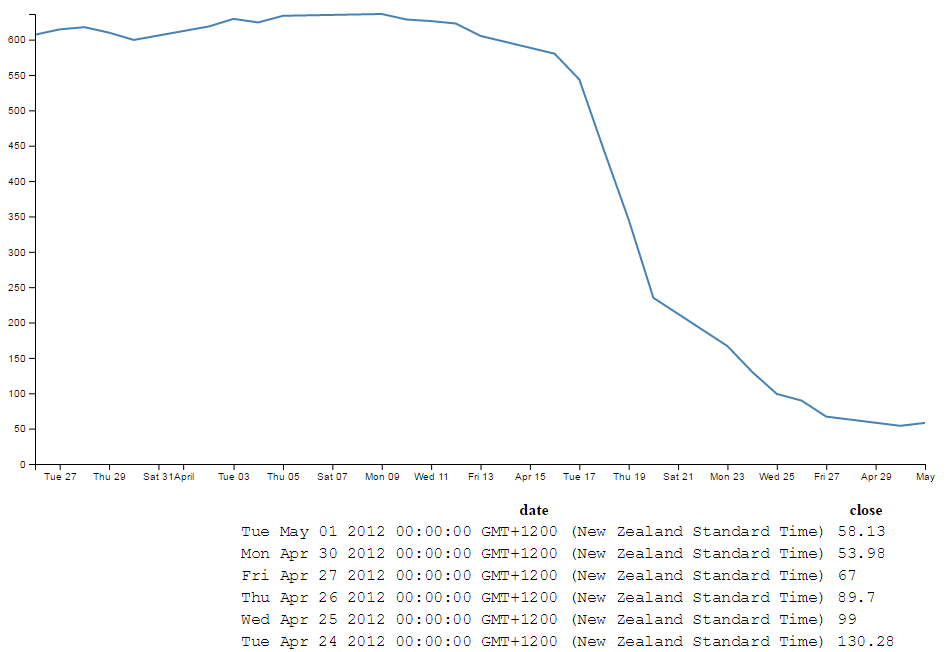

Check it out…

Not quite as we has originally envisaged?

Indeed, the date has taken it upon itself to expand from a relatively modest format of day-abbreviated month-two digit year (30-Apr-12) to a behemoth of a thing (Mon Apr 30 2012 00:00:00 GMT+1200 (New Zealand Standard Time)) that we certainly didn’t intend, let alone have in our data.csv file.

What’s going on here?

I’m no expert, but this is what I tell myself is happening. The JavaScript code recognises and deals with the ‘date’ variable as being a date/time (not a string of numbers, letters and characters). Therefore, when we proceed to display the variable on the screen, the browser says, “this is a date / time value, therefore in lieu of any other instructions, I will format it in the following way”. This is perfectly valid and we could work through a method of re-formatting the code to display in a specific way, but there is a simpler way to solve the problem. Hence the third small but cunning change to our original code.

A small but cunning change…

Our table has decided to develop a mind of it’s own and format the date time as it sees fit. Well fair enough (I for one welcome our web time formatting overlords). How do we convince it to display the values in their natural form?

Well, one solution that we could employ is to not tell the JavaScript that our date value in the data is actually time. In that condition, the code should treat the values as an ordinary string and print it directly as it appears.

The good news is that this is pretty easy to do. Where originally we had a block of data that consisted of date and close, all at different times, we will now add a new variable called date1 which will be the variable that we convert to a time and draw the graph with. Leaving date to be the text string that will be printed in our table.

How to do it?

It’s actually remarkably easy. Just change the following lines in the basic line graph code to amend date to date1 and you’re good to go.

.x(function(d) { return x(d.date1); })

d.date1 = parseTime(d.date);

x.domain(d3.extent(data, function(d) { return d.date1; }));

The middle line is probably the most significant, since this is the point where we declare date1, assign a time format and bring a new column of data into being. The others simply refer to the data.

So we’ll make those small changes and now we can return to explain the d3.js code…

Explaining the d3.js code (reloaded).

So back we come to explain what is going on in the d3.js code that we presented a page or two back. Obviously it’s a fairly large chunk, and we can break it down into two chunks.

The first chunk we’ll look at is in fact the last part of the code that look like this;

// render the table

var peopleTable = tabulate(data, ["date", "close"]);

This portion simply calls the tabulate function using the date and close columns of our data array. Simply add or remove whichever columns you want to appear in your table (so long as they are in your data.csv file) and they will be in your table. The tabulate function makes up all of the other part of the added code.

So we come to the first block of the tabulate function;

// The table generation function

function tabulate(data, columns) {

var table = d3.select("body").append("table")

.attr("style", "margin-left: 400px"),

thead = table.append("thead"),

tbody = table.append("tbody");

Here the tabulate function is declared (function tabulate) and the variables that the function will be using are specified ((data, columns)). In our case data is of course our data array and columns refers to ["date", "close"].

The next line appends the table to the body of the web page (so it will occur just under the graph in this case). Then we do something slightly sneaky. The line .attr("style", "margin-left: 400px"), is actually not the code that was used to produce the table with the huge date/ time formatted info on. I deliberately used .attr("style", "margin-left: 0px"), for the huge date / time table since it’s job is to indent the table by a specified amount from the left hand side of the page. And since the huge date time values would have pushed the table severely to the right, I cheated and used 0 instead of 400. For the purposes of the final example where the date / time values are formatted as expected, 400 is a good value.

The next two lines declare the functions we will use to add in the header cells (since they use the <th> tags for content) and the cells for the main body of the table (they use <td>).

The next block of code adds in the header row;

// append the header row

thead.append("tr")

.selectAll("th")

.data(columns)

.enter()

.append("th")

.text(function(column) { return column; });

Here we first append a row tag (<tr>), then we gather all the columns that we have in our function (remember they were ["date", "close"]) and add them to our row using header tags (<th>).

The next block of code assigns the row variable to return (append) a row tag (<tr>) whenever it’s called …

// create a row for each object in the data

var rows = tbody.selectAll("tr")

.data(data)

.enter()

.append("tr");

… and it is in the following block of code…

// create a cell in each row for each column

var cells = rows.selectAll("td")

.data(function(row) {

return columns.map(function(column) {

return {column: column, value: row[column]};

});

})

.enter()

.append("td")

.attr("style", "font-family: Courier") // sets the font style

.html(function(d) { return d.value; });

… where we select each row that we’ve added (var cells = rows.selectAll("td")). Then the following five lines works out from the intersection of the row and column which piece of data we’re looking at for each cell.

The last four lines take that piece of data (d.value) and wrap it in table data tags (<td>) and place it in the correct cell as HTML.

It’s a very neat piece of code and I struggle to get my head around it, but that doesn’t mean that I can’t appreciate the cleverness of it :-).

Wrap up

So there we have it. Hopefully enough to explain what is going on and perhaps also enough to convince ourselves that D3 is indeed more than just pretty pictures. It’s all about the Data Driven Documents.

As mentioned earlier, there is a copy of the code and the data file for this example at github and in the code samples bundled with this book (simple-graph-plus-table.html and data.csv). A live example can be found on bl.ocks.org.

More table madness: sorting, prettifying and adding columns

When we last left our tables they were happily producing a faithful list of the data points that we had in our graph.

But what if we wanted more?

From the original contributors that bought you tables (Shawn Allen on Google Groups) and some neat additions from Christophe Viau comes extra coolness that I didn’t include in the previous example :-).

There is a copy of the code and the data file for this example at github and in the code samples bundled with this book (simple-graph-plus-table-plus-addins.html and data2.csv). A live example can be found on bl.ocks.org.

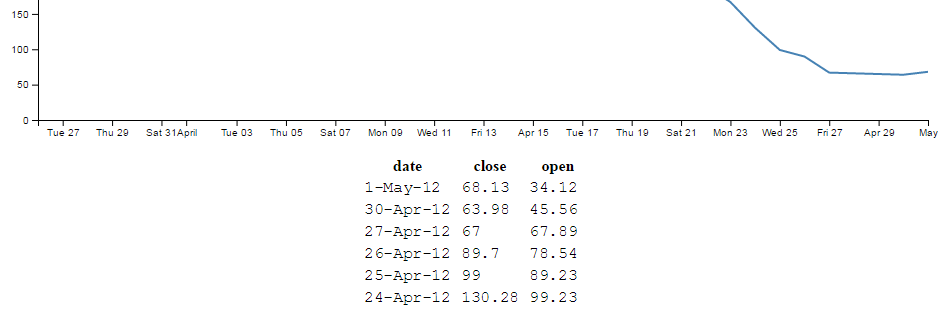

Add another column of information:

Firstly, lets add another column of data to our table. To do this we want to have something extra in our csv file to use, so let’s resurrect our old friend data2.csv that we used for the graph with two lines previously. All we have to do to make this a reality is change the reference that loads data.csv to data2.csv here;

d3.csv("data2.csv", function(error, data) {

From here (and as promised in the previous chapter), it’s just a matter of adding in the extra column you want (in this case it’s the open column) like so;

var peopleTable = tabulate(data, ["date", "close", "open"]);

So can we go further?

You know we can…

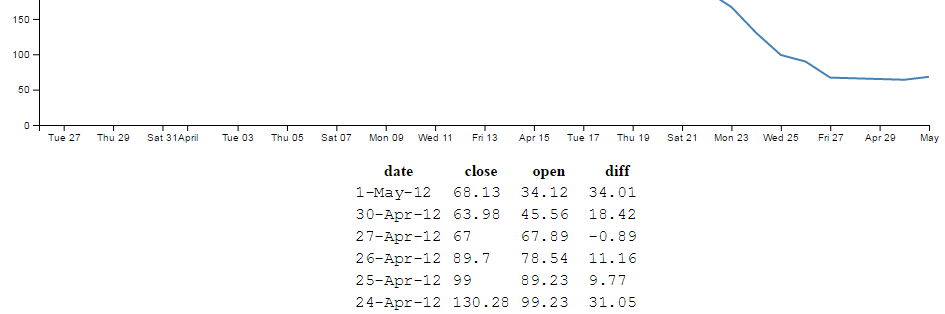

In the section where we format our data, lets add another column to our array in the form of a difference between the close value and the open value (and we’ll call it diff).

// format the data

data.forEach(function(d) {

d.date1 = parseTime(d.date);

d.close = +d.close;

d.open = +d.open; // <= added this for tidy house keeping

d.diff = Math.round(( d.close - d.open ) * 100 ) / 100;

});

(the Math.round function is to make sure we get a reasonable figure to display, otherwise it tends to get carried away with decimal places)

So now we add in our new column (diff) to be tabulated;

var peopleTable = tabulate(data, ["date", "close", "open", "diff"]);

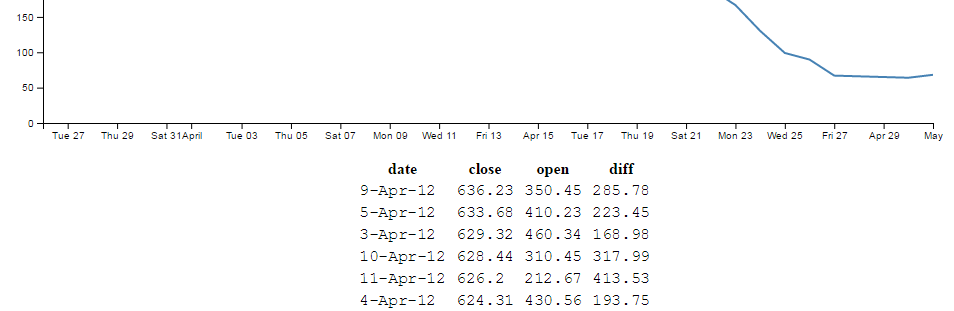

Sorting on a column

So now with our four columns of awesome data, it turns out that we’re really interested in the ones that have the highest close values. So we can sort on the close column by adding the following lines directly after the line where we declare the peopleTable function (which I will include in the code snipped below for reference).

// render the table

var peopleTable = tabulate(data, ["date", "close", "open", "diff"]);

peopleTable.selectAll("tbody tr")

.sort(function(a, b) {

return d3.descending(a.close, b.close);

});

Which works magnificently;

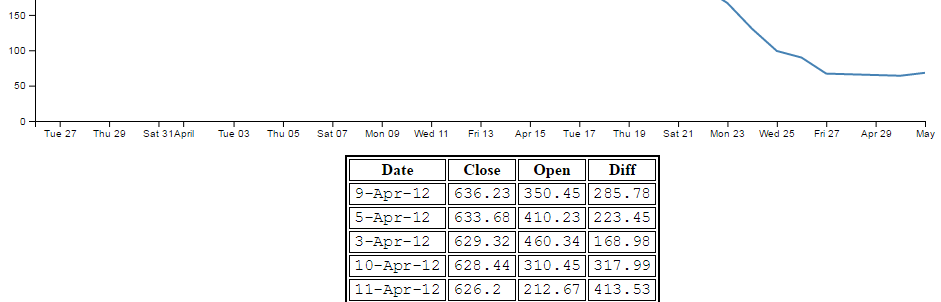

Prettifying (actually just capitalising the header for each column)

Just a little snippet that capitalises the headers for each row to make them look slightly more authoritative.

Add the following lines of code directly below the block that you just added for sorting the table;

peopleTable.selectAll("thead th")

.text(function(column) {

return column.charAt(0).toUpperCase() + column.substr(1);

});

This is quite a tidy little piece of script. You can see it selecting the headers (selectAll("thead th")), then the first character in each header (column.charAt(0)), changing it to upper-case (.toUpperCase()) and adding it back to the rest of the string (+ column.substr(1)).

With the ultimate result…

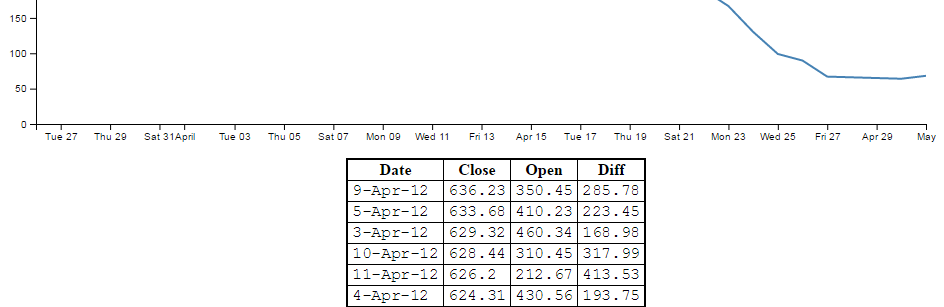

Add borders

Sure our table looks nice and neatly arranged, but would a border look better?

Well, here’s one way to do it;

All we need to do is add a border style to our table by adding in this line here;

function tabulate(data, columns) {

var table = d3.select("body").append("table")

.attr("style", "margin-left: 200px") // <= Remove the comma

.style("border", "2px black solid"), // <= Add this line in

thead = table.append("thead"),

tbody = table.append("tbody");

(don’t forget to move the comma from the end of the margin-left line)

And the result is a tidy black border.

OK, so what about the individual cells?

No problem.