Chapter 10: The Sixth Core Drive: Scarcity & Impatience

Scarcity and Impatience is the sixth core drive of the Octalysis Framework. It is the drive that motivates us simply because we are either unable to have something immediately, or because there is great difficulty in obtaining it.

We have a natural tendency to want things we can’t have. If a bowl of grapes were sitting on the table, you may not care about them; but if they were on a shelf just beyond your reach, you would likely be thinking about those grapes: “Are they sweet? Can I have them? When can I have them?”

Personally, Core Drive 6 was the last Core Drive I learned about and is the one that intrigues me the most, particularly because this core drive can feel completely unintuitive, irrational, and emotionally difficult to utilize.

In this chapter we’ll explore this Black Hat/Left Brain Core Drive, understand its powers, and learn about some game techniques that harness it for behavioral change.

The Lure of being Exclusively Pointless

South Park, a popular American animated sitcom created by Trey Parker and Matt Stone, has many lessons to teach us about human behavior (once you get past the potty-mouth cursing and gory scenes).

In one of the episodes, “Cartmanland”23, the controversial main character Eric Cartman inherits $1 million from his deceased grandmother. He decides to use most of the funds to buy a struggling theme park just to entertain himself there without being stuck in lines.

Instead of trying to improve the business, Cartman makes a full 38-second TV commercial to show how amazingly fun “Cartmanland” is and emphasizes that no one besides himself can enjoy it. “So much fun in Cartmanland, but you can’t come!” is the catchy slogan.

After realizing he needs more money to hire a security guard to keep his friends out, Cartman starts to accept two customers a day to pay for the security costs. He soon realizes that he needs to pay for other things such as maintenance, utilities, and other operational services, so he begins to open the park up to three, four, tens, and then hundreds of people each day.

Since people all saw how inaccessible Cartmanland was for them, when they learned that it was accepting more people, they rushed to get in.

Eventually, everyone wanted to go to Cartmanland and it went from being a near-bankrupt theme park to one of the most popular parks in the region. Experts within the episode even called the “You Can’t Come!” campaign a brilliant marketing ploy by the genius millionaire Eric Cartman.

Unfortunately, with more people in his precious park, Cartman became miserable and eventually sold it back to the original owner. Subsequently, he lost his money due to tax mismanagement, which is typical of Cartman.

What you see here is a classic example of scarcity through exclusivity. Though this is an exaggerated example, in this chapter you will see how our brains have a natural tendency to pursue things just because they are exclusive.

On the other side of popular media, in the movie Up in the Air24, protagonist Ryan Bingham, played by George Clooney, is a corporate “downsizer” that flies all over the place to help companies lay off employees. In a conversation with the young and ambitious status-quo disruptor Natalie Keene, played by Anna Kendrick, Bingham gives us a lesson about the value of scarcity, status, rewards, and exclusivity, as he explains about his obsession with accumulating airline miles.

Ryan Bingham: I don’t spend a nickel, if I can help it, unless it somehow profits my mileage account.

Natalie Keener: So, what are you saving up for? Hawaii? South of France?

Ryan Bingham: It’s not like that. The miles are the goal.

Natalie Keener: That’s it? You’re saving just to save?

Ryan Bingham: Let’s just say that I have a number in mind and I haven’t hit it yet.

Natalie Keener: That’s a little abstract. What’s the target?

Ryan Bingham: I’d rather not…

Natalie Keener: Is it a secret target?

Ryan Bingham: It’s ten million miles.

Natalie Keener: Okay. Isn’t ten million just a number?

Ryan Bingham: Pi’s just a number.

Natalie Keener: Well, we all need a hobby. No, I- I- I don’t mean to belittle your collection. I get it. It sounds cool.

Ryan Bingham: I’d be the seventh person to do it. More people have walked on the moon.

Natalie Keener: Do they throw you a parade?

Ryan Bingham: You get lifetime executive status. You get to meet the chief pilot, Maynard Finch.

Natalie Keener: Wow.

Ryan Bingham: And they put your name on the side of a plane.

Natalie Keener: Men get such hard-ons from putting their names on things. You guys don’t grow up. It’s like you need to pee on everything.

Beyond the collection, status, and achievement (Core Drives 4, 5, and 2), one thing that was very important for Ryan was that “I’d be the seventh person to do it. More people have walked on the moon.” This shows that because it’s something that he (along with billions of others) couldn’t get right now, he valued obtaining it more. It was simply more appealing because of how exclusive it was.

The Value of Rare Pixels

In the previously mentioned game Geomon, gamers try to capture monsters in order to battle each other. The game is similar to Pokemon, but influenced by the environment where the gamers are physically located based on their phone GPS, such as being next to a river or a desert.

In Geomon, there are certain monsters that can only be found in very limited or special situations. Because some of these monsters are extremely rare, people are willing to spend real money in order to obtain them.

One such example is the Mozzy, a blazing fox made of fire.

The Mozzy can only be caught on hot days and close to an office run by the Mozilla Organization - creators of the Mozilla Firefox browser. This means, for a game that has players throughout the world, it is extremely difficult, sometimes impossible for the average person to capture a Mozzy. In the forums, people sometimes say, “This summer my parents are taking me to San Francisco. I’m going to rent a car and drive down to Mountain View. Maybe I’ll catch a Mozzy. So excited!”

This drive is further illustrated with the live comments made by Geomon players, through in-game chat, during game play. In the following screenshot I randomly took while playing, notice how desperate users are in obtaining a Mozzy. Emphasized with all caps – “I’LL DO ANYTHING FOR A MOZZY.”

Though it seems rather extreme, the desperate plea above is surpassed by the following conversation below:

Here, you see “Vincent7512” claim (adjusted for capitalization), “I wish I had a single Mozzy, then, at this point in my life, I could die happy.”

Now you would expect that when someone says this, others would respond with, “Come on… get a life! It’s just a game!” But no. Three lines down, you see “Valeriefox18” echo the same sentiment, “me too vincent :( me too.”

Here is a community of players who are so desperate about getting Mozzys that instead of playing the game more, they hang out on the chat board just to mope about it and feel “connected” to one another (CD5 Relatedness). Pretty extreme right?

Another example of this within Geomon is the Laurelix, the magnificent golden phoenix.

In order to catch a Laurelix, you need to be at a location that has an extremely high temperature, possibly over 110 Fahrenheit or 40 Celsius. The result of this design was, at one point there were only 3 players in the entire world that owned a Laurelix. As you might imagine, everyone wanted one too. Once the game studio even received a call from the mother of a player, saying, “My son has been sick for two whole weeks, and he said nothing could cheer him up unless he had a Laruelix. I don’t know what that is, but he said you had it. I’m willing to pay $20 for a Laurelix. Can you give that to my son?”

Interestingly, the Mozzy and Lauralix are not the most powerful geomons in the game – there are plenty of geomons that are more powerful than they are. But because these two are so difficult to obtain, their perceived value increased immensely, helping the company better monetize their game.

What’s amazing is that when something is this scarce, it has a tremendous amount of stickiness to it also. As an advisor for the company, I played the game for a while (okay, more than a while), facilitated the online communities, and helped the company redesign and rebalance their entire ability skill trees and combat systems. After that, I became a passive advisor, quit the game, and moved on to my “other work.”

For an entire seven months, I haven’t been playing, nor thinking about the game (except when meeting the CEO and advising them on management and monetization strategies). But one day I was traveling for work and found myself at a place that was excruciatingly hot, to the point where I felt like I was burning if directly exposed to the sun.

At that moment, instead of shouting or complaining about it, the first thing that came to my mind and mouth was, “I wonder if I could catch a Laurelix here…” This of course confused my client who was giving me a tour of his great country.

Even though, again, I didn’t care about playing the game anymore and haven’t played for over half a year, because a Laurelix was so scarce, I naturally thought that, “Well, when I can capture one, I probably should capture it!”

The Leftovers aren’t all that’s Left Over

Most of us would like to believe that we make purchasing decisions based on the price and quality of a good. A purchase is seen as a very rational exchange of money for an item that we desire. If the price were greater than the “utility,” or happiness that we derive from the valuable, then we don’t make the purchase.

However, psychological studies have shown again and again that this is only partially true. We buy things not because of their actual value, but rather based on their perceived value, which means many times our purchases aren’t very rational.

In 1975, researchers Worchel, Lee, and Adewole conducted an experiment to test the desirability of cookies in different cookie jars25. The experiment featured two cookie jars, one with ten cookies in it, and the other with only two. Though the cookies were exactly the same, the experiment revealed that people valued the cookies more when only two were available in the jar. They valued those cookies more, mainly for two reasons: 1) Social Proof – everyone else seems to prefer those cookies for some reason, and 2) Scarcity- people felt that the cookies were running out.

In a second experiment conducted by the team, subjects watched as the number of cookies in the “ten-cookie” jar were reduced to two cookies, while the other group saw the “two-cookie” jar get filled up to ten cookies. In this case, people started to value the former more and devalue the latter. When people saw that there was now an abundance in the first jar which earlier had only two cookies, they valued these even less than those from the “ten-cookie” jar of the first experiment where there were ten cookies to begin with.

Here we see that, when there is a perceived abundance, motivation starts to dwindle. The odd thing is, our perception is often influenced by relative changes instead of absolute values. People with $10 million would perceive their wealth differently (and feel differently) if they only had $1 million the year before, versus if they had $1 billion the year before.

Persuasively Inconvenient

As illustrated in the examples above, our brains intuitively seek things that are scarce, unavailable, or fading in availability.

Oren Klaff is a professional sales pitcher and fundraiser who claims to close deals through a systematic method which he calls neuroeconomics, a craft that combines both neuroscience and economics. By digging deep into our psychology and appealing to what he calls the “croc” brain, the method utilizes various Core Drives such as Social Influence & Relatedness, Scarcity & Impatience, as well as the upcoming Core Drive 7: Unpredictability & Curiosity and Core Drive 8: Loss & Avoidance.26

In his book Pitch Anything27, Klaff explains the concept of Prizing, and how it ties into three fundamental behaviors of our “croc” brains:

- We chase that which moves away from us

- We want what we cannot have

- We only place value on things that are difficult to obtain

His work suggests that, instead of ABS – Always Be Selling, salespeople should practice ABL – Always Be Leaving. If you are always leaving the discussions, it means that you are not desperate, are highly sought after, and not dependent on this deal. You are the Prize. Klaff claims that, when you correctly do this, money will flow in.

Through his methods, Klaff has raised over $450 million and claims to continue so at a rate of $2 million a week.

It is oddly true that as we place limitations on something, it becomes more valuable in our minds. In Yes! 50 Scientifically Proven Ways to Be Persuasive, the authors share how Colleen Szot revolutionized her infomercials by simply changing the call-to-action line from “Operators are waiting, please call now,” to, “If operators are busy, please call again.28”

Why would this be? In the first case, viewers can imagine operators sitting around, waiting to answer calls and take orders for products that may be of marginal value. In the second case viewers will perceive that the operators are struggling to answer a flood of calls just to keep up with the demand on orders. Even though this message suggests an inconvenience to buy a product, the perceived scarcity alone is enough to motivated people to call quickly before the product potentially runs out.

My father is a diplomat for Taiwan, and sometimes he would talk to a colleague who was deployed to a former communist country in Eastern Europe. I once heard the colleague say, “If you see a line on the street, don’t even waste time finding out what they are in line for. Just get in line. It must be something essential like soap or toilet paper. It doesn’t matter if you have money. If there is no toilet paper in the region, your money is useless.” Here, the sheer inconvenience driven by scarcity and social proof can compel a comparably wealthy person to stand in line for hours.

In Pitch Anything, Oren Klaff also brings up another example where BMW released a special-edition M3 that required the buyer to sign a contract promising to keep it clean and take care of the special paint. Without this promise in writing, they won’t even allow you to purchase the car! In this case, BMW is inflating its value so that the buyer will believe it is a special and exclusive privilege to drive the car. Maybe that’s why the hard-to-get strategy in dating culture is so prevalent. Through Core Drive 6: Scarcity & Impatience, you can keep your prospective partner on their toes.

Curves are better than Cups in Economics

When I was studying Economics at UCLA, the one fundamental lesson that my professors regularly talked about was the Supply and Demand curve. It basically explains that if the price of an item drops, the demand will increase. If the item becomes completely free, the curve will indicate the maximum number of buyers that will acquire it.

However, if you study behavioral psychology, gamification, and/or Human-Focused Design, you will find that there is another side to the story. As it turns out, Scarcity is another driving force of consumer behavior. In economic theory, scarcity is well understood, but only in the sense of objective limits matched against the consumer’s utility derived from a purchase.

This is different from the Scarcity we are discussing in this chapter, which is related to Perceived Scarcity instead of Objective Scarcity. Sometimes objective scarcity is present without a person ever feeling or knowing it. At other times there is a sense of perceived scarcity without a true limit being present.

The difference here is that neo-classical economic theory starts off with three key assumptions29:

- Consumers behave rationally

- Consumers have full and relevant information

- Consumers try to maximize their utility (or happiness derived from economic consumables)

But in the real world, the first two assumptions almost never hold true - people are often irrational and never have perfect information. Sometimes they react to pricing in another, more surprising way: the more expensive something is, the higher the value (utility) is placed on it. This leads to increased demand. As a result, sales may actually increase with pricing.

Normally, if an item were free (the extreme right of the demand curve), everyone who would want this product would obtain it for free. Say hypothetically, 100 people want this product for free. But in certain scenarios, if the product is unusually expensive, people who previously didn’t care might suddenly desire it. Now sales may exceed 150 items! Because of this scarcity effect, a modified demand curve in some products might produce a C-Shape instead of a diagonal line moving down to the right.

Scarcity works because people perceive something to be more valuable if it is more expensive or less attainable. Because people don’t have “perfect information,” they generally do not fully know their utility for a certain good. Therefore, they rely on cues - such as how expensive or limited something is - to determine its value. If everyone wants it, it must be good! This goes hand-in-hand with the last chapter on Core Drive 5: Social Influence & Relatedness.

Of course, at some point, the C-Curve needs to curl back towards the left (zero in quantity) as the item becomes exceedingly expensive beyond anyone’s wealth, producing a reverse S-Shape on the graph. Objective Scarcity (of money) ultimately still wins over Perceived Scarcity at large extremes.

“This guy’s not expensive enough.”

I’ve personally seen numerous examples, both first and second hand, where increasing the price actually allowed people to sell more.

In 2013, one of my clients was trying to choose between two Public Relations service providers, one who charged $8,000 per month and the other $10,000 per month. I informed him that I thought the $8,000/mo provider would deliver better services. However, my client remained doubtful, feeling that the $10,000/mo provider must be more competent to charge that price. I told him that just because one service provider has the audacity (I used a more vulgar term) to charge more doesn’t mean he is better. But my client still couldn’t decide.

Ultimately my client decided to use both of the services for a period of three months. Though expensive, this was great for me personally because it allowed me to gather valuable data on their actual performances and draw comparisons. After the period was up, it was clear that the $8,000/mo provider was exceptional, while the provider at $10,000 per month proved to be very disappointing. My client fired the $10K guy and retained the $8K guy after that.

What’s odd is that if the weaker service provider recognized that he was less suitable for the project and only charged $6000 instead of $10,000, he might not have been given a second thought. His aggressive pricing strategy yielded him a new opportunity and $30,000 more! Of course the ultimate lesson here should be to focus on creating strong value for your client- so you don’t lose your job after 3 months.

On another occasion, I had a client that needed a Cost Per Click (CPC) campaign audit. I contacted a friend from Eastern Europe who was the best in the industry. Since I had done some favors for him in the past, I was able to persuade him to help my client with a free audit, for which he normally would have charged thousands for.

Though my client was excited about the arrangement, he hesitated and moved very slowly. I pressed my client on this and he said, “What worries me is the free price … is he really as good as you say he is?” He had perceived that my friend’s service was not really valuable because it was offered for free. That’s why it might have been more advantageous to charge a smaller fee such as $500 for the audit, instead of providing it pro bono.

“I Don’t Feel Good When My Pocket Is Too Full After A Purchase”

This situation doesn’t just happen with high-end services. In the book Influence: Science and Practice, Robert Cialdini also describes a story of a friend who ran an Indian jewelry store in Arizona that tried to sell some high quality turquoise pieces during the peak tourist season30.

Despite her constant efforts to promote, cross-sell, and emphasize these pieces to shop visitors, no one seemed interested in purchasing them. Finally, the night prior to an out-of-town buying trip, the owner concluded that she needed to lower the prices and make the pieces more attractive to her customers. As a result, she left a note for her head salesperson with instructions to reduce the prices by “x½.”

However, the salesperson misunderstood the note, and mistakenly doubled the price instead. Upon returning a few days later, the owner was pleasantly surprised to learn that all the pieces had been sold. Doubling the price on each item had actually allowed her to sell more because their perceived value had increased.

Since you don’t do anything with jewelry other than show it off to others (or yourself), the value is usually based on perception as opposed to functionality. You may quickly dismiss the value of an ugly and cracked pottery piece on the shelf, until someone told you that it was made 1,200 years ago for a historically significant event. The pottery itself did not functionally or aesthetically become more valuable, but its perceived value immediately went up due to the principles of scarcity.

Up to this point, you may have observed that the high-price principle within Core Drive 6 works powerfully for luxury items that serve little functional purpose such as jewelry, or expensive services that provide essential expertise. Surprisingly, it also works with everyday functional items.

Just a week prior to writing this chapter, upon realizing my knee pains were getting worse, I decided to visit a sports utility store. I wanted pick up some knee braces for hiking or when I’m walking up and down the stairs during phone meetings. When I entered the store, I saw that there were two types of braces, one for $24.99 one another for $49.99.

I thought to myself, “Well, my knees are very important to me. I better not spare a few extra bucks and end up with busted knees down the road.” As an extension to this thought, I reached out for a pair of $49.99 braces and bought them.

It didn’t occur to me until writing this chapter and searching for examples, that I automatically assumed that the more expensive knee braces were better than the cheaper ones. I didn’t even bother to carefully read the product descriptions. If you were to ask me how the $49.99 one was better than the $24.99 one, I wouldn’t be able to give you an answer. I would likely say something along the lines of, “Well, the $49.99 one is more expensive, so I’m sure it offers better protection for my knees or feels more comfortable. Probably both.”

This was very powerful because, in my head, I was not thinking about the actual differences between the two knee braces. I was simply thinking whether I wanted to, “save money and get lower quality,” or “not skimp and invest in quality goods for my long-term health.”

Daniel Kahneman, author of Thinking: Fast and Slow, refers to our brain’s neocortex as our “System 2,” which broadly controls our conscious thinking31). Since the processing capabilities of our brain’s neocortex are limited, we regularly rely on mental shortcuts, known as heuristics, without noticing them. In this situation, the mental shortcut was that “expensive equals quality” when it may not have necessarily been the case.

Another mental shortcut can be, “The Expert said it with confidence - I will assume it to be true without looking too deeply into it.” Sometimes people let pass some obvious blunders and oversights simply because the authoritative expert or scientist said so. They let their “System 2” become lazy and simply become motivated by Core Drive 5: Social Influence & Relatedness.

Perhaps I am alone in my silliness and financial irresponsibility in buying knee braces simply because they were more expensive. But the chances are, at some point in your life you have also taken mental shortcuts based on assumptions that may not always hold true. Perhaps you have purchased a bottle of wine or detergents based on very little information other than the price, and disdained some selections simply because the merchant labeled it at a low price.

Game Techniques within Scarcity & Impatience

You have learned more about the motivational and psychological nature of Core Drive 6: Scarcity & Impatience. To make it more actionable, I’ve included some Game Techniques below that heavily utilize this Core Drive to engage users.

Dangling (Game Technique #44) and Anchored Juxtaposition (Game Technique #69)

Many social and mobile games utilize game design techniques within Core Drive 6: Scarcity & Impatience to heavily monetize on their users. One of the more popular combinations among games are what I call Anchored Juxtaposition (Game Technique #69) and Dangling (Game Technique #44).

For instance, when you go on Farmville, you initially may think, “This game is somewhat fun, but I would never pay real money for a stupid game like this.” Then Farmville deploys their Dangling techniques and regularly shows you an appealing mansion that you want but can’t have. The first few times, you just dismiss it, as you inherently know it wouldn’t be resource-efficient to get it. But eventually you start to develop some desire for the mansion that’s constantly being dangled there.

With some curiosity now compelling you, a little research shows that the game requires 20 more hours of play before you can afford to get the mansion. Wow, that’s a lot of farming! But then, you see that you could just spend $5.00 and get that mansion immediately. “$5 to save 20 hours of my time? That’s a no-brainer!” Now the user is no longer paying $5 to buy some pixels on their screen. They are spending $5 to save their time, which becomes a phenomenal deal. Can you see how game design can influence people’s sense of value by alternating between time and money?

The humorous part about this phenomenon is that most of these games can be played for free, and yet people are spending money, just so they could play less of the game. In this sense, it is hard to determine if the game itself is truly considered “enjoyable” or “fun.” As opposed to Core Drive 3: Empowerment of Creativity & Feedback, this Black Hat Left Brain Core Drive is more about being persuasive and obsessive, but users don’t necessarily enjoy the process.

An important factor to consider when using the Dangling technique is the pathway to obtaining the reward. You have to allow the user to know that it’s very challenging to get the reward, but not impossible. If it is perceived as impossible, then people turn on their Core Drive 8: Loss & Avoidance modes and go into self-denial. “It’s probably for losers anyway.”

For example, if the banner of an exclusive club is dangled in front of you, but you find out that the prerequisite to join is that you must be a Prince or Princess through royal blood, you might not even look at what the organization does. Instead, you may think, “Who cares about a bunch of stuck up, spoiled brats.” Because there is no chance of qualifying, it activates Core Drive 8 as an Anti Core Drive – the drive to not execute the Desired Action.

However, if the banner said, “Joining Prerequisite: Prince/Princess by royal blood, OR individuals who have previously ran a marathon.” Now you are motivated, and might even ponder the effort required to run a marathon. As long as there is a realistic chance to get in, the Scarcity through exclusivity is enough to engage you. Interestingly, at this point you still haven’t even determined what the organization actually does! Without any information on its actual function, the human-focused motivation of scarcity is compelling enough for you to consider running a marathon.

This leads to a game technique I call Anchored Juxtaposition. With this technique, you place two options side by side: one that costs money, the other requiring a great amount of effort in accomplishing the Desired Actions which will benefit the system.

For example, a site could give you two options for obtaining a certain reward: a) Pay $20 right now, or b) complete a ridiculous number of Desired Actions. The Desired Actions could be in the form of “Invite your friends,” ‘Upload photos,” and/or “stay on the site for 30 days in a row.”

In this scenario, you will find that many users will irrationally choose to complete the Desired Actions. You’ll see users slaving away for dozens, even hundreds of hours, just so they can save the $20 to reach their goal. At one point, many of them will realize that it’s a lot of time and work. At that moment, the $20 investment becomes more appealing and they end up purchasing it anyway. Now your users have done both: paid you money, and committed a great deal of Desired Actions.

It is worth remembering that rewards can be physical, emotional, or intellectual. Rewards don’t have to be financial nor do they need to come in the form of badges - people hardly pay for those. In fact, based on Core Drive 3: Empowerment of Creativity & Feedback principles, the most effective rewards are often Boosters that allow the user to go back into the ecosystem and play more effectively, creating a streamlined activity loop in the process.

With Anchored Juxtapositions, you must have two options for the user. If you simply put a price on the reward and say, “Pay now, or go away,” many users will go back into a Core Drive 8 denial mode and think, “I’m never gonna pay those greedy bastards a single dollar!” - and then leave. Conversely, if you just put on your site, “Hey! Please do all these Desired Actions, such as invite your friends and complete your profile!” users won’t be motivated to take the actions because they clearly recognize it as being beneficial for the system, but not for themselves.

Only when you put those two options together - hence Juxtaposition, do people become more open to both options, and often commit to doing both consecutively as time goes by. But does this work in the real world, outside of games? You bet.

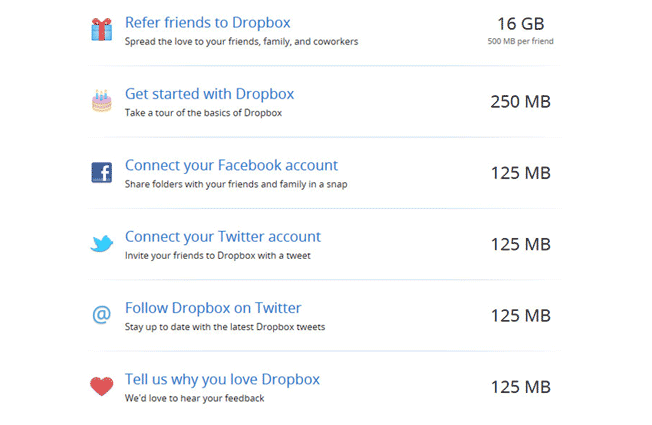

Dropbox is a File Hosting Service based in San Francisco that has obtained extraordinary popularity and success. When you first sign-up to Dropbox, it tells you that you could either a) pay to get a lot of storage space, or b) invite your friends to get more space. In the beginning, most people started with inviting their friends.

Eventually, many of those users who are completing the Desired Actions decide that inviting/harassing their friends is a lot of work, but they still need a lot of storage space, so they end up becoming paying users (just like I did). Again, because of the Anchored Juxtaposition, users commit both the Desired Action, and pay for the full product.

Dropbox’s viral design, along with a great seamless product design, accelerated the company’s growth to a point where it reportedly raised over $300 million, with a valuation of around $10 billion and revenues above $200 million in 2013. Not too shabby for a company that didn’t exist seven years prior to that.

Magnetic Caps (Game Technique#68)

Magnetic Caps are limitations placed on how many times a user can commit certain Desired Actions, which then stimulates more motivation to commit them.

When I consult with my clients, I often remind them that they should rarely create a feeling of abundance. The feeling of abundance does not motivate our brains. Scarcity, on the other hand, is incredibly motivating towards our actions. Even if the user committed the ultimate Desired Action by paying a lot of money, a persuasive system designer should only give people a temporary sense of abundance. After a few weeks or months, the feeling of scarcity should crawl back again with new targets for the user to obtain - perhaps after they have used up all of their virtual currencies and needing to purchase their next batch.

A great system designer should always control the flow of scarcity, and make sure everyone in the system is still striving for a goal that is difficult, but not impossible, to attain. Failure to do so would cause a gratifying system to implode with users abandoning it for better grounds.

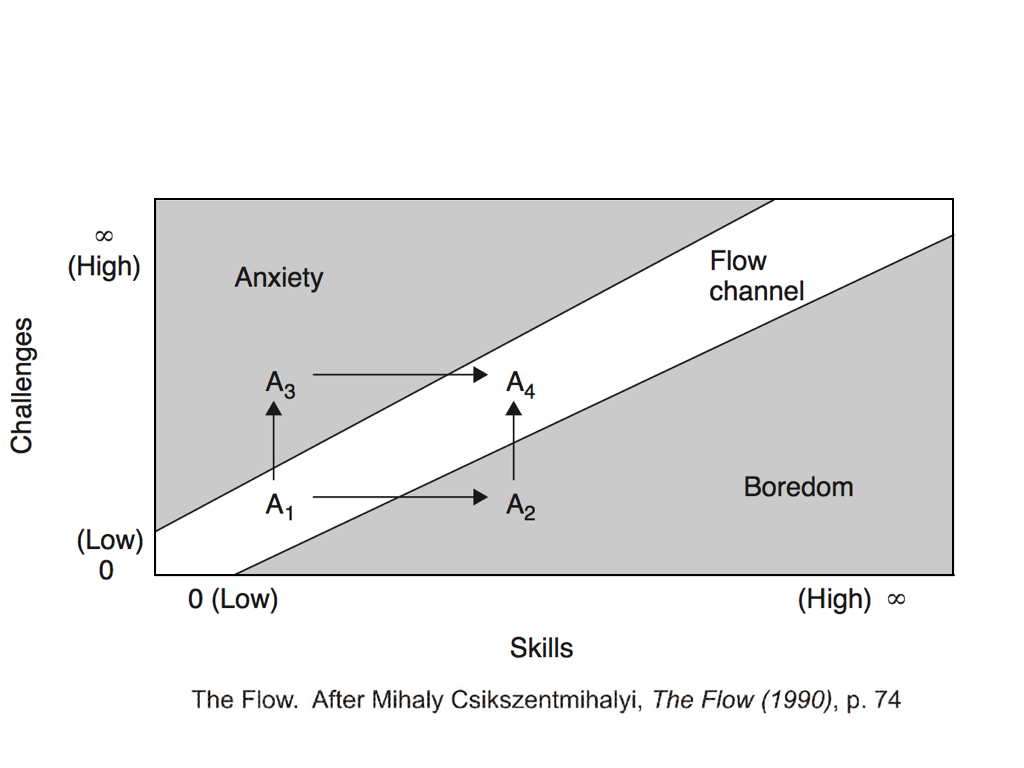

This plugs nicely into Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s Flow Theory32, where the difficulty of the challenge must increase along with the skill set of the user. Too much challenge leads to anxiety. Too little challenge leads to boredom.

There have been many interesting studies showing that by simply placing a limit on something, people’s interest in it will increase. If you introduce a feature that can be used as much as people want, often few will actually use it. But once you place a use limit on the feature, more often than not, you will find people enthusiastically taking advantage of the opportunity.

In Brian Wansink’s book Mindless Eating: Why We Eat More Than We Think, he describes that when a grocery store just displays a promotional sign that says, “No Limit Per Person,” people often just buy a few of the promoted item33. However, if the sign were to say, “Limit 12 Per Person,” people will start to buy more – in fact, 30% - 105% more, depending on other variables. That’s another odd characteristic of scarcity: by drawing limits, we’re drawn towards the limit.

This means that you should place a limit on an activity if you want to increase a certain behavior. Of course, you don’t necessarily want the Magnetic Cap to limit the activity so much that you lose more than you gain. The best way to set a limit is to first find the current “upper bound” of the desired metric, and use that as the cap to create a perceived sense of scarcity but doesn’t necessarily limit the behavior. A behavior designer could speculate “Even though we want users to select an unlimited number of hobbies, 90% of our users choose fewer than five hobbies on our website.” In this case, it would be appropriate to set a limit at five or six hobbies instead of having no limits.

What about the 10% of users who go beyond six hobbies - the “power users”, you ask? Aren’t they important? Yes they are (and if you asked that question, it means you have been thinking about user motivation and experience phases, which is great). This is when you let the power users unlock more capabilities and have the limit rise as they continue to prove their commitment, as described with the Evolved UI technique below. Again, you still want to let these power users to confront a Magnetic Cap at the top, so that they always feel a sense of Scarcity, but not have it truly limit their activities.

Appointment Dynamics (Game Technique #21)

Another way to reinforce this Core Drive is to harness the scarcity of time. The best known game technique that leverages this is the Appointment Dynamic. Popularized by Seth Priebatsch’s TEDx Boston talk on The Game Layer on Top of the World34, Appointment Dynamics utilize a formerly declared, or recurring schedule where users have to take the Desired Actions to effectively reach the Win-State.

One of the most common examples are Happy Hours, where by hitting the Win-State of showing up at the right time, people get to enjoy the reward of 50% off appetizers and beer. People expect the schedule and plan accordingly.

Appointment Dynamics are powerful because they form a trigger built around time. Many products don’t have recurring usage because they lack a trigger to remind the person to come back. According to Nir Eyal, author of Hooked35, External Triggers often come in the form of reminder emails, pop-up messages, or people telling you to do something.

On the other hand, Internal Triggers are built within your natural response system for certain experiences. For instance, when you see something beautiful, it triggers the desire to open Instagram. Facebook’s trigger, on the other hand, is boredom.

A friend once told me how one day he was using Facebook and suddenly felt bored. Surprisingly, He instinctively opened a new tab on his browser and typed in “Facebook.com.” Once the website loaded, he was shocked, “Oh my. I was already on Facebook. Why did I open Facebook again?” Again, this is the power of an Internal Trigger that connects to a feeling as common as boredom - for instance, what do you do when you are waiting in line?

With Appointment Dynamics, the trigger is time. My garbage truck comes every Tuesday morning, so on Monday nights, I automatically have an internal alarm clock reminding myself to take out the garbage. If the garbage truck comes out every day, I may procrastinate until my garbage overflows before taking it out.

One extremely innovative example (and I rarely call things “innovative”) of a company utilizing the Appointment Dynamic is a large Korean shopping center named eMart. The company realized that their traffic and sales are usually great during most hours of the day, but during lunch time, foot traffic and sales drops significantly. To motivate people to show up during lunch time (Desired Action), they mustered up the principles of Core Drive 6: Scarcity & Impatience and a bit of Core Drive 7: Unpredictability & Curiosity. They ended up launching a campaign called “Sunny Sale” and built an odd-looking statue in front of their stores.

On its own, this statue looks fairly abstract and doesn’t seem to resemble anything. During noon time, however, the magic starts to happen. When the sun reaches its greatest height at noon, the shadow of this statue suddenly transforms into a perfect QR Code where people can scan with their mobile phones and see unique content.

Isn’t that cool? Because the QR Code can only be scanned within a limited window between 12PM to 1PM, people are now rushing to get there in time. Honestly, at that point, it doesn’t matter what the QR Code is about – the scarcity and intrigue (stemming from Core Drive 7: Unpredictability & Curiosity) is enough to get people to show up. In the case of eMart, the QR code links to a coupon that consumers can redeem immediately for a purchase online.

This tactic reportedly improved eMart’s noon time sales by 25%. Not bad when you are already the largest player in the industry.

Torture Breaks (Game Technique #66)

By now you may have noticed that another kind of game technique of Core Drive 6: Scarcity & Impatience can utilize “Impatience”, which means not allowing people to do something immediately. In the old days, most console games tried to get users to stay on as long as possible. If a player were “glued to the screen” for five hours straight, it would be a big win for the game. Nowadays, social mobile games do something completely different.

Many social mobile games don’t let you play for very long. The game will let you play for thirty minutes, and then tell you “Stop! You can’t play anymore. You need to come back 8 hours later - because you have to wait for your crops to grow / you need to wait for your energy to recharge / you need to heal up.”

For some parents who don’t understand Core Drive 6, this design makes them very happy. “That’s great! These game designers are so responsible – now my son’s play time will be limited!” But in fact, what they don’t recognize is that the game is implementing what I call Torture Breaks to drive obsessive behavior.

A Torture Break is a sudden and often triggered pause to the Desired Actions. Whereas the Appointment Dynamic is more based on absolute times that people look forward to (Every Monday morning the garbage truck will come; on July 4th when you open the app, you will get a huge bonus), Torture Breaks are often unexpected hard stops in the user’s path toward the Desired Action. It often comes with a relative timestamp based on when the break is triggered, such as “Return 5 hours from now.”

My differentiation between the two Game Techniques may differ somewhat from Priebatsch’s definition. Though they often work hand in hand together (sometimes after a Torture Break is triggered, an Appointment Dynamic follows), it is important to note the difference so you can plan your gamified systems accurately.

In the example of social mobile games, because the player was forced to stop playing, they will likely continue to think about the game all day long. Often, they will log back in after three hours, five hours, six hours, just to check if they are finally able to play - even though their brain knows as a fact that the allotted eight hours haven’t passed yet.

If the player was allowed to play for as long as they wanted – say three hours, they would likely become satisfied, stop playing, and not think about the game for a day or two. Therefore, an omniscient game designer would perhaps allow them to play for two hours and fifty-nine minutes, and then trigger the Torture Break. At this point, they will be obsessively trying to figure out how to play that final one minute. Sometimes the game may even provide another option – “pay $1 to remove the Torture Break immediately!”

Another game, Candy Crush, which by many metrics is considered to be one of the most successful games in the world, making approximately $3 million per day36, incorporates the Torture Break very well. After losing a life, the game pauses and forces you to wait 25 minutes before you can gain another life and proceed to the next level.

This draws players to constantly think about those slow-passing 25 minute intervals, and makes it difficult to plan other activities while being occupied by the obsession.

Of course, the game also gives you two options: ask your friends to give you a life (Social Treasure), or pay right now (Anchored Juxtaposition). See how all these game techniques work together to become a holistic motivational system towards Desired Actions?

Accidental Fails sometimes become a Blessing

Another good example of the Torture Break is the “Fail Whale” in the early years of Twitter. The Twitter site was often down in 2007. Though this frustrated many users, they waited more eagerly for the service to return, while talking about it on Facebook.

When the site was down, users would only see a “404 Error Page” displaying the iconic Fail Whale – a large whale being pulled out of the water by many struggling birds.

Twitter’s combination of “limitations” – you can’t go over 140 characters, can’t tweet over X times a day, can’t access the site 60% of the time – compelled many to spend countless hours on Twitter, even though there truthfully wasn’t much to do there in those early days.

I’ve seen other cases where people were planning to retire from playing a game, but then encountered issues due to massive server problems. Instead of quitting, they checked the app every day to see whether they could play it or not. Even though they planned to quit, they needed to quit on their own terms. When these players were prevented from playing because they “couldn’t,” their desire to play actually increased.

What made the situation worse was that players would occasionally be able to play the game, only to experience another crash. If it were down indefinitely, people would lose interest. But by “sometimes working,” the game would take on an addictive appeal. Remember, for Core Drive 6 to work, users have to perceive that obtaining the goal is possible, or else they fall into a Self-Denial Mode driven by Core Drive 8: Loss & Avoidance.

This is also similar to some relationships I’ve witnessed, where one person wants to break up with the other, plans the breakup for months, and suddenly gets dumped by the other person. Even though the person wanted to break up from the start, when they gets dumped, they may become obsessed with wanting to get back together with the other person. They want the separation to be on their terms. But when forced to separate, it becomes a Torture Break that makes them yearn for a reconciliation.

This behavior is much like people pulling on a slot machine lever, hoping for, but not necessarily expecting, good results. The same effect happened with Twitter, where users became obsessed with checking the site each minute to see if the service had been reestablished, subsequently becoming delighted when it ultimately returned.

Evolved UI (Game Technique #37)

One of the techniques that I often recommended to my clients, but have faced resistance on, is the Evolved UI - short for “Evolved User Interface”. The problem with most user interfaces is that they’re too complex during the Onboarding stage, while too basic for the Endgame.

In the popular gaming phenomenon World of Warcraft, if you monitor the top-level players, their interface could make you dizzy. There may be close to a dozen little windows open, all with different stats, options, and icons. It displays a plethora of information about how your teammates are doing, how the boss is doing, where everyone is, and your own resources. So much information that you can barely see the animation of your own character fighting! It truly is one of the most complex user interfaces around.

However, World of Warcraft, along with many other well-designed games, never starts off with this level of complexity. At the beginning they only provide a few options, buttons, and icons. But as you reach more Win-States, you unlock more options, skills, and capabilities. With the help of effective Step-by-step On-boarding Tutorials, Narratives, and Glowing Choices, a beginner never gets confused about what to do at the start.

Based on the concept of Decision Paralysis, if you give users twenty amazing features at the beginning, they feel flustered and don’t use a single one. But if you give them only two or three of those features (not just one, since our Core Drive 3 loves choice), and have them slowly unlock more, then they begin to enjoy and love the complexity.

However, the Evolved UI concept is very difficult for a company to implement emotionally, because it feels weird to withhold great features and functionalities from the user. For the designer though, it is important to acknowledge that withholding options can drive more behavior towards the Desired Action. Just because it makes users feel uncomfortable doesn’t mean it’s necessarily bad for you, nor for the user.

One company that did implement the Evolved UI concept was Sony, calling it Evolution UI38(in fact, I modified my game technique name to fit Sony’s, just to avoid semantical ambiguity within the industry).

Though the Android smartphone system developed by Google was very powerful, Sony realized that it had a high learning curve that could fluster beginning users. To address the situation, they launched the Evolution UI, which presented a very limited set of core options during the Onboarding process.

Once users have shown that they have mastered the basic UI, such as opening 5 apps, they unlock an achievement, which in turn unleashes new features. In this way, the difficulty of the user experience never surpasses the skill sets of the user, following the principles of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s Flow Theory mentioned earlier.

So what’s the consequence of having an UI that is too complex at the beginning? Google Plus. As mentioned earlier, even with a lot of great features and functions, Google Plus did not have sticky traction because of the learning curve it required. Most mainstream users feel confused when they are accidentally pushed onto Google Plus when using Youtube or Gmail; and thus quickly leave the platform.

Gmail, on the other hand, implements a small version of Evolved UI, which manifested itself in the form of Gmail Labs. In Gmail, users are provided a basic set of features and functionalities by default. But there are many cool features that they can be unlocked through the “Labs” tab under Gmail Settings, opening up complex but helpful features once the user feels ready.

Great! So now what?

Of course, understanding Scarcity & Impatience doesn’t mean that startups should shut down their servers on purpose, or set up fake and corny limitations in their systems. Some users may become obsessed, but you could likely turn away many others who quickly jump into denial mode and never come back.

The most obvious application for start-ups based on Core Drive 6 principles is to launch with a confident pricing strategy. Instead of just offering everything for free or making them easily available, a more premium pricing model or well-structured exclusivity design can increase the confidence of users/buyers resulting in increased conversion rates.

Of course, if you price an item beyond your target market’s capability to afford, this would obviously backfire. But more often than not, when customers don’t buy your product, it’s not because they can’t afford it, it’s because the perceived value they have for your product is not worth the cost. Sometimes that cost is in the form of time, energy investment, or reputation in their organizations.

Beyond pricing, you may want to create a sense of exclusivity for each step during the Discovery and Onboarding stages. A design, where the service makes them feel that it’s uniquely for them and that they are only qualifying for access - similar to Facebook’s early marketing strategy.

Every step of the way, you want to show users what they may want but can’t have - just yet. Scarcity only exists as a motivator when people know the reward actually exists, so when in doubt, Dangle about (but don’t say you learned that from my book during court). For actions that lead to rewards and investments, consider using more restrictive options. Placing a cap on how many actions a person can take (or investments that they can make) will cause them to desire the actions more.

By increasing perceived value, customers and users are more likely to stay engaged and take greater interest in your venture. This will help insure you from giving out all your hard-earned work for close to nothing.

Core Drive 6: The Bigger Picture

Scarcity and Impatience is considered a Black Hat Core Drive, but if used correctly, it can be very powerful in driving motivation. Often, Core Drive 6 is a first source of generating Core Drive 3: Empowerment of Creativity & Feedback in the system. Overcoming scarcity can cause a higher sense of Core Drive 2: Development & Accomplishment.

When fused with Core Drive 7: Unpredictability and Curiosity, Core Drive 6 becomes a great engine to drive online consumer action. Finally, working alongside Core Drive 8: Loss & Avoidance, Scarcity and Impatience becomes a powerful force that not only pushes for action, but pushes for action with extremely strong urgency.

To get the most out of the book, Choose only ONE of the below options to do right now:

Easy: Think about a time where you wanted something, mostly because it was exclusive, or because you felt you were uniquely qualified. Try to describe the nature of that feeling from Scarcity & Impatience.

Medium: Think about a time when a company attempted to implement a corny form of Scarcity, and it backfired because it caused people to go into denial. What could the company do to actually implement principles of Scarcity correctly?

Hard: Think about how you can implement combinations of Dangling, Torture Breaks, Evolved UI, and Anchored Juxtaposition into one of your own projects. Does it automatically increase the desire for other Core Drives? Or does it hamper it? Does it drive long-term engagement, or short-term obsession?

Share what you come up with on Twitter or your preferred social network with the hashtag #OctalysisBook and check out what ideas other people have.

Share your Knowledge!

Beyond sharing my own research and interests, I regularly have guest bloggers posting their research on gamification, motivational psychology, behavioral design and much more on my blog YukaiChou.com39. If you have interesting knowledge to share through your own experiences and research, consider sending a message through the site and offer a guest piece to promote your work. I’ve done all this work so you could learn a little bit from me. I would love to get the opportunity to learn from you too!