Table of Contents

- Chapter One: Effects of Extensive Reading on Japanese Language Learning

- Chapter Two: Raising a Biliterate Child in Japan: A Case Study of a Bicultural Family

- Chapter Three: Project of an Extensive Reading Course for Brazilian Languages and Literature Teachers In-service

- Chapter Four: Longitudinal Case Study of a 7-year Long ER Program

- Chapter Five: Public Libraries Support ER of Adult EFL Learners in Japan

- Chapter Six: Exploring Teacher’s Practice and Impacts of Extensive Reading on Japanese EFL University Students

- Chapter Seven: An Evaluation of Progress Measurement Options for ER Programs

- Chapter Eight: Implementing Extensive Reading in Japanese as L2 Environment:A Case Using Facebook to Build a Reading Community

- Chapter Nine: Making Quizzes for M-Reader and the MoodleReader Quiz Module

- Chapter Ten: Three Steps Toward Authenticating the Practice and Research of Extensive Reading at a Japanese University

Chapter One: Effects of Extensive Reading on Japanese Language Learning

Eri Banno & Rie Kuroe

Okayama University, Japan

Abstract

This paper reports the implementation of extensive reading in a Japanese as a Second Language class and discusses extensive reading’s effects for Japanese language learning. The extensive reading class was offered in a Japanese university to 32 intermediate to advanced Japanese language learners. The results of questionnaires of two types indicated that by the end of the course, the students thought that they could improve their reading ability, they changed their reading strategy, and they began to desire reading more in Japanese. The students’ comments also supported these findings. These results therefore indicate that extensive reading can be a powerful method for Japanese as a Second Language learning.

Introduction

Extensive reading has been widely incorporated in second or foreign language classrooms. However, few extensive reading studies explore the method’s potential in Japanese as a Second or Foreign Language (JSL/JFL) contexts. This paper reports on the implementation of extensive reading in JSL classes at a Japanese university and discusses extensive reading’s effects for Japanese language learning. First, we will describe the extensive reading class in our university Japanese course. We will then report the method and results of the questionnaire conducted in the extensive reading class. Finally, from the study’s results, we will discuss the effects of extensive reading.

Extensive Reading for JSL/JSL Learners

Extensive reading is an approach where people read quickly and enjoyably with adequate comprehension without using a dictionary (Extensive Reading Foundation, 2011). To implement extensive reading, Day and Bamford (2002) have suggested the “Top Ten Principles for Teaching Extensive Reading.”

- The reading material is easy.

- A variety of reading material on a wide range of topics must be available.

- Learners choose what they want to read.

- Learners read as much as possible.

- The purpose of reading is usually related to pleasure, information and general understanding.

- Reading is its own reward.

- Reading speed is usually faster rather than slower.

- Reading is individual and silent.

- Teachers orient and guide their students.

- The teacher is a role modal of a reader.

In JSL/JFL contexts, teachers can implement extensive reading in their classrooms as Japanese graded readers have become available since 2006. However, extensive reading is still uncommon in JSL/JFL classrooms and few articles report on the implementation of this technique. Hitotsugi and Day (2004) collected 266 Japanese children’s books and asked elementary Japanese learners to read outside class. In their survey, they found an increase in students who responded positively toward studying Japanese. Interviews and surveys from other studies (Kawana, 2012; Matsui, Mikami, & Kanayama, 2012; Ninomiya & Kawakami, 2012; Ninomiya, 2013) also showed the positive effects of extensive reading when students freely read graded readers in class.

Extensive Reading Class in the Japanese Language Course

Overview

In 2013, the extensive reading class was implemented in a Japanese language course at the target university. It was an elective class so that students’ participation was voluntarily. The classes were 90-minutes long and were held for 15 weeks. The participating students’ levels ranged from pre-intermediate to advanced.

The class’ objectives are to help students: (1) enjoy reading in Japanese, (2) read without translation, (3) read faster, (4) increase receptive vocabulary, and (5) read habitually. In order to attain these goals, we asked students to read easy books, skip/guess what they do not understand, focus on the overall meaning, not read slowly, and select another book if the current one is too difficult.

Furthermore, the course’s requirements include (1) weekly book reports and comment sheets, (2) three poster presentations, (3) number of the books they read, and (4) class attendance and participation. In the book report, students wrote on whether the books were interesting, how difficult the books were, and short summary of the books. For the comment sheet, students wrote about their thoughts on their reading ability, such as their reading speed and problems. In the poster presentations, students created a poster of their favorite book and used it to inform other students about the book in the class. Furthermore, the number of books students read was also included in the grade. However, as we intended the students to read both extensively and enjoyably, the number of books read only accounted for 10% of the final grade. Students who read over 60 books were awarded full marks; the points decreased as the number of the books read decreased.

Classes typically began with the teacher introducing some books to the students, who then quietly read their self-selected books. While the students read, the teacher talked to each student individually to ask whether they have any problems or what they thought of the books they read. Approximately 10 minutes before the end of class, students form small groups to discuss the most interesting books they read that day.

Materials

Currently, over 100 Japanese graded readers exist; with five levels between beginner and intermediate levels, there are about 10 - 30 books per level. Considering the number of students, their Japanese levels, and their varied interests, we thought that more books were needed for this study. Therefore, we prepared comic books, picture books, and children books for this class. A total number of 264 books were selected; Table 1 shows the breakdown of these books based on their category. The students were also encouraged to read other books as long as the books’ levels were appropriate.

Table 1. Books for the Extensive Reading Class

| Category | Number of Books |

| Graded Readers | 101 |

| Comics | 61 |

| Picture Books | 44 |

| Books for Elementary School Students | 58 |

| Total | 264 |

Research Questions

This study attempts to answer the following research questions:

1.Does extensive reading change students’ perception of their language abilities? 2.Does extensive reading change students’ perception of their reading style? 3.Does extensive reading change students’ attitude toward reading?

Method

**Participants **

There were 32 students participating in the extensive reading class at the target university. Their Japanese levels ranged from pre-intermediate to advanced. Of the 32, 11 students were from the United States, five students from China, three students each from France, Germany, and Thailand, two students from Korea, one student each from Lithuania, Philippines, Russia, Serbia, and Taiwan. Furthermore, 31 of the 32 participants were exchange students who have been in Japan for one semester or just arrived in the country.

Data

Questionnaire A (pretest and posttest)

Questionnaire A was conducted twice (in the first and last class). The questionnaire aimed to identify changes in students’ perceptions of their Japanese language ability, reading styles, and attitudes toward reading. The question types include questions on students’ Japanese language ability (5 questions), strategy or habit (5 questions), anxiety (4 questions) and comfort (5 questions). The questions on strategy or habit were based on Hitotsugi and Day (2004), and the questions on anxiety and comfort were taken from Yamashita (2013). The questionnaire was written both in Japanese and English. Students responded to the questionnaire using a 5-point Likert scale with 5 being “strongly agree” and 1 being “strongly disagree.

Questionnaire B (posttest)

Questionnaire B was conducted in the final class. This questionnaire elicited student feedback on the class. Students were also asked whether they thought their language ability improved. The questionnaire was again written both in Japanese and English. Students again responded using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “5” (strongly agree) to “1” (strongly disagree).

Results

Questionnaire A (pretest and posttest)

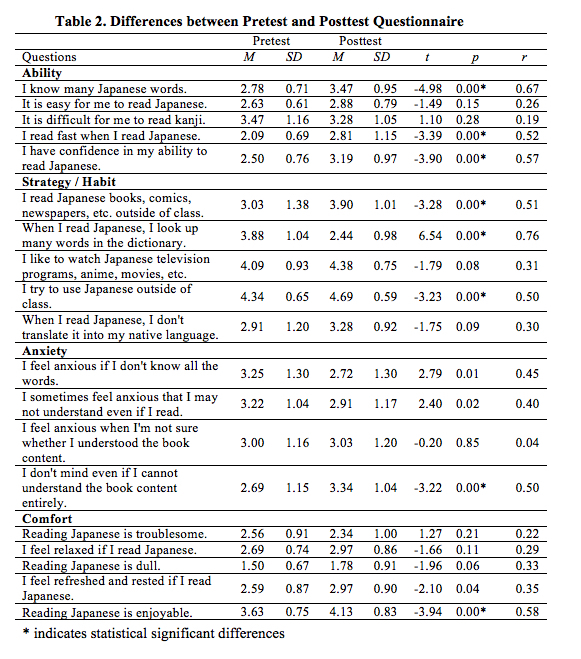

Table 2 shows the difference between the pre- and posttest of Questionnaire A. The difference was analyzed using the paired t-tests. Furthermore, as multiple t-tests were conducted, the alpha level was adjusted using the Holm’s method.

The three “Ability” questions were found to be statistically significant between the pre- and posttest. This indicates that students perceived an increase in vocabulary, reading speed, and reading ability by the end of the course.

Additionally, the three “Strategy or Habit” questions were also found to be statistically significant. The question “When I read Japanese, I look up many words in the dictionary” was significantly lower in the posttest, indicating that students relied on dictionaries less by the end of the course. On the other hand, the question “I read Japanese books, comics, newspapers, etc. outside of class” received significantly higher scores in the posttest. This suggests that by the end of the course, students were reading more outside of class. The question “I try to use Japanese outside of class” was also significantly higher in the posttest. It must be noted that these differences might be due to the factors besides extensive reading. Most of the participants have lived in Japan for less than a year, thus these differences may have emerged as they adjusted to living in Japan and made more Japanese friends. Lastly, while the question “When I read Japanese, I don’t translate it into my native language” scored higher in posttest, it was not statistically significant.

Only one of the “Anxiety” questions was statistically significant (i.e., “I don’t mind even if I cannot understand the book content entirely”). The two questions, “I feel anxious if I don’t know all the words” and “I sometimes feel anxious that I may not understand even if I read” were not statistically significant but had very low alpha levels. This indicates that students feel less anxious about not understanding every word or content by the end of the course.

The “Comfort” question on “Reading Japanese is enjoyable” was significantly higher in the posttest, indicating that students enjoyed reading more by the end of the course.

Questionnaire B (posttest)

In the final class, students were asked how they perceived extensive reading. Table 3 shows the mean scores and standard deviations of the questions on extensive reading. All the questions received high mean scores (i.e., above 4.0). More specifically, every question other than “I came to like reading” had very high mean scores.

Table 3: Questions on Extensive Reading

| Questions | M | SD |

| Extensive reading was interesting. | 4.47 | 0.66 |

| Extensive reading is effective for Japanese language learning. | 4.56 | 0.66 |

| I came to like reading. | 4.09 | 0.95 |

| I want to continue extensive reading in Japanese. | 4.53 | 0.66 |

The students were also asked if they thought their Japanese language abilities had improved through extensive reading. Table 4 shows the mean and standard deviations of the questions on students’ language ability. Only the questions on listening, writing, speaking had lower mean scores, which was expected for a reading class.

Table 4. Questions on Language Ability

| Questions | M | SD |

| My reading speed became faster. | 4.22 | 0.82 |

| I could learn kanji. | 4.19 | 0.68 |

| I could learn vocabulary. | 4.19 | 0.63 |

| I could improve my reading skills. | 4.44 | 0.61 |

| I could improve my listening skills. | 2.78 | 1.22 |

| I could improve my writing skills. | 3.38 | 0.70 |

| I could improve my speaking skills. | 3.19 | 0.81 |

Discussion

Research question 1 asked “Does extensive reading change students’ perception of their language abilities?” As shown in Table 3, the mean score for “Extensive reading is effective for Japanese language learning” was very high, indicating that students strongly felt that extensive reading effectively improved their Japanese language ability. Additionally, the results of Questionnaire A show that students believe they have improved vocabulary, reading speed, and reading confidence. Furthermore, the results of Questionnaire B show that the students think that they could improve their reading skills, their reading speed became faster, and they could learn kanji and vocabulary. These results indicate that by reading extensively the students think that aspects of their reading ability such as reading speed, vocabulary, and kanji knowledge improved.

On a comment sheet for the final class, Student A from Thailand wrote about changes in her reading speed and extensive reading’s usefulness: “My reading speed is better. I don’t use the dictionary a lot when I find unknown words now. By reading Japanese books I can learn new words and practice grammar, so it is very useful.”

Research question 2 asked, “Does extensive reading change students’ perception of their reading style?” The student’ comment above demonstrates her change in dictionary use when encountering unknown words. Additionally, Questionnaire A’s results show that students looked up words less frequently when reading by the end of the course. These results suggest that students changed their dictionary-use strategy when reading,

On a comment sheet, Student A wrote about the advantages of reading without a dictionary:

When I see unknown words, it is better not to look at a dictionary. When I look at a dictionary, I can’t follow the content and the book becomes uninteresting. If you want to know the meaning, it is OK to look at a dictionary once or twice. The more I read, the better I like reading.

This student believes that constantly referring to a dictionary restricts her understanding of the books and her overall enjoyment. The last sentence from the above excerpt also suggests the student increased reading enjoyment through reading extensively.

On the other hand, no statistical difference was found in “When I read Japanese, I don’t translate it into my native language.” Although the reason for this result is unclear, the results may due to how the rating scale was inappropriate for this question; it would be more appropriate to ask them to choose from “always” to “never” rather than “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.”

Research question 3 asked, “Does extensive reading change students’ attitude toward reading?” The results of Questionnaire A show decreased student anxiety toward not understanding everything when reading by the end of the course.

Student B from Korea wrote that her fear for reading unknown words changed during the course. In the 11th week, this student wrote: “I noticed my reading has changed. I felt uneasy when I saw unknown words, but not now.” By week 15, the same student stated the following: “My reading speed is faster and I don’t have fear for reading, and I am really happy. I am going to read various books during summer vacation.”

The results of Questionnaire A also show that students think reading Japanese is enjoyable and that they increasingly read outside of class. Questionnaire B also indicates that students think extensive reading is interesting and want to continue reading extensively in Japanese.

Student C from China commented that reading easy books is interesting and enjoyable: “I first wanted to challenge difficult books, but now I am enjoying reading. When I read easy books, I can learn more.” Other students mentioned their desire to continue reading even after the course finishes. One of them was Student D from Thailand.

I read various books. My reading speed is faster and I always enjoyed reading. I promise that I will not quit reading even after the class is over. I want to read many books from now on.

By reading easy books, the students felt less anxious and found reading in Japanese enjoyable. This feeling of enjoyment seems to encourage their desire to read more in Japanese.

Conclusion

In this paper, we first described the Japanese extensive reading class at our target university. We then reported the method and results of the questionnaire conducted in this class. Finally, from the study’s results, we discussed the effects of extensive reading. The results of the study indicate that at the end of the course, students perceived improved reading ability, changed reading strategy, and increased desire for reading in Japanese. By reading many easy books that interest them, and trying to read fast without looking at a dictionary, the students notice their improvement in their reading skills as well as changes in their reading styles. The students’ comments also support these findings. These results suggest that extensive reading can be a powerful method for language learning.

References

Day, R. & Bamford, J. (2002). Top ten principles for teaching extensive reading. Reading in a Foreign Language, 14, 136–141.

Extensive Reading Foundation (2011). The Extensive Reading Foundation’s Guide to Extensive Reading. Retrieved from http://erfoundation.org/ERF_Guide.pdf.

Hitotsugi, I. & Day, R. (2004). Extensive reading in Japanese. Reading in a Foreign Language, 16(1), 20–39.

Kawana, K. (2012). Jookyuu gakushuusha o taishoo to shita tadoku jugyoo – kaki Nihongo kyooiku C7 crasu ni okeru jissen [Extensive reading for advanced Japanese learners: Implementation in summer Japanese class C7]. ICU Japanese Language Education Research, 9, 61-73.

Matsui, S., Mikami, K., & Kanayama, Y. (2012). Shokyuu, chuukyuu Nihongo koosu ni okeru tadoku jugyoo no jissen hookoku [Practical reports of implementation of extensive reading in the beginner and intermediate Japanese language course]. ICU Japanese Language Education Research, 9, 47-59.

Ninomiya, R. & Kawakami, M. (2012). Tadoku jugyoo ga jooimen ni oyobosu eikyoo – dooki zuke no hoji, sokusin ni shooten o atete [Effects of extensive reading on JSL learners’ motivation]. Journal of Global Education, 3, 53-64.

Ninomiya, R. (2013). Tadoku jugyoo ga shokyuu gakushuusha no naihatuteki dooki zuke ni oyobosu eikyoo [Effects of extensive reading on beginning level learners’ motivation]. Journal of Global Education, 4, 15-29.

Yamashita, J. (2013). Effects of extensive reading on reading attitudes in a foreign language. Reading in Foreign Language, 25(2), 248-263.

Chapter Two: Raising a Biliterate Child in Japan: A Case Study of a Bicultural Family

Sanborn Brown

Osaka Kyoiku University, Japan

Sae Matsuda

Setsunan University, Japan

Abstract

This paper reports on a case study of a bicultural family in Japan. Krashen (2004:61) claims “Often, those who ‘hate to read’ simply do not have access to books.” The bicultural family in this study tried to make sure of the opposite and provide books for their child. A Japanese/American child, who obtained sufficient input during her early developmental phase, has learned to read autonomously and achieved a highly proficient level of English. Several factors that have presumably contributed to her literacy will be discussed.

Introduction

Although Smith (1994) and others have reported some successful case studies, for a native speaker of Japanese living and attending school in Japan, becoming bilingual is no easy feat. The survey results reported by Noguchi (1996a) reveal that the two language management strategies (“one parent-one language” strategy and home/community language strategy) “often face a wide range of problems, especially after the children reach school age and when families have more than one child” (p.245).

Therefore, becoming biliterate in English (and Japanese) is no doubt even more daunting. As Noguchi (1996b) argues, learning to read in one’s native language while living in one’s native country is hard enough; to attempt to learn a language as different as English is from Japanese is all the more so. The written and grammatical systems have nothing in common. With the exception of loan words, the spoken language is totally different as well.

Why bother with adding a second, unrelated language when school, community, and in many cases home life are conducted in Japanese? The obvious answers would include future professional opportunities, being able to communicate with relatives and non-Japanese speakers, using email, a feeling of affinity with a parent’s native written language, etc. Beyond these personal reasons, research has shown that multiple advantages accrue to those who attain a high level of literacy in two languages: creativity and divergent thinking (Baker, Rudd, & Pomeroy, 2001), metalinguistic awareness (Bialystok, Luk, & Kwan, 2005), cognitive flexibility (Hakuta & Dias, 1985), intercultural communicative competence (Lüdi, 2006), and enriched linguistic repertoire (Pavelenko, 2009).

Once one has decided to go down the path of biliteracy, the issue of how to proceed arises.

The Case Study

Participant

The participant of this case study is Mona Matsuda. She was born in Kyoto, Japan, in 1998, and is currently 17-years-old. Her father is an American national who has lived in Japan for more than two decades. Her mother is a Japanese national who spent two years in the United States.

Mona’s dominant language is Japanese (or, more specifically, Kyoto dialect), her second language English. She has spent her entire life in Kyoto, and attended local day care centers and public neighborhood elementary and junior high schools. She is now a second year high school student at a public school in Kyoto.

Language & Culture Environments

From the time of her birth, Mona was immersed in an unusual home language environment. For the first 5-6 years of her life, her parents alternated languages by day. For example, if on Monday they spoke in English, Tuesday would be a “Japanese” day. In recent years, however, Japanese has become the dominant language of the family.

Still, within the family, the parents have roughly maintained for 17 years a “one parent-one language” policy. That is, the father – with some exceptions (e.g., in a situation in which mono-lingual Japanese are present) – only speaks in English to Mona. Similarly, the mother only speaks in Japanese to Mona. Outside of the home, Mona’s linguistic environment is overwhelmingly Japanese.

Both parents’ knowledge of the two languages helped communication because Mona, in the first years of her life, responded only in Japanese to Father’s questions in English; this did not, however, cause a communication breakdown. After Mona started speaking English with her father, Mother participated in Japanese, or Father sometimes joined in (in whichever language) when Mona and Mother were talking in Japanese. In other words, when it comes to a family conversation, the language spoken was flexible and depended on the situation: all Japanese, two people speaking English/one speaking Japanese, or two speaking Japanese/one speaking English.

Mona was fortunate to have cultural input at an early age as well. Her household celebrated events from both cultures. She enjoyed the traditional Japanese feast on New Year’s day and threw beans to drive off evil spirits at Setsubun; similarly, she went egg hunting on Easter and trick-or-treading on Halloween. She also visited her American family and relatives once or twice a year.

Bedtime Reading and More

From a very young age, both parents read to Mona every night. The nightly reading selection was left to Mona, who sometimes chose English books for her mother and, conversely, Japanese books for her father to read. (In this event, her father would often read in Japanese and then summarize the story in English.)

In addition to the above routine, the parents provided additional access to books with frequent visits to local libraries and bookstores. Whenever and wherever they traveled, finding a good bookstore was at the top of things to do. They read on the train and the plane.

Her grandparents were also generous providers of books for her. Especially her Japanese grandfather, also a book lover, enjoyed taking her to bookstores and buying several books every time they went. He even gave her book coupons after he won in Go (an Asian board game) tournaments.

Mona liked Japanese folktales as well as Dr. Suess’s ABC. She enjoyed demons and monks while she was fascinated by princesses and fairies. Her favorite books at an early stage included The Very Hungry Caterpillar (by Eric Carle), Good Night Moon (by Margaret Wise Brown), The Going to Bed Book & Moo, Baa, La La La! (by Susan Boynton), and In a Dark Dark Room and Other Scary Stories (by Alvin Schwartz).

As she grew older, the effects of the “one parent-one language” system became more apparent. At bedtime her father read English books such as Harry Potter, and her mother read translated versions of Astrid Lindgren books in Japanese. Her mother had enjoyed reading these 40 year-old books when she was young. The end of the Harry Potter series coincided with the time in which the parents faded out of bedtime reading.

Other English Input

Other English input included videos and television programs, primarily from the United States. She started with Sesame Street and PBS kids programs and moved on to the Disney Channel. Another bilingual family gave her Barney home videos, which she enjoyed for a while. Her favorite videos, however, included The Wizard of Oz, The Sound of Music, and the Indiana Jones series. She often asked her parents to tell those stories at bedtime as well. She watched most of the Disney movies on video while she saw the latest animated movie at a movie theater. (This sometimes meant waiting for a night showing so that they could watch it in English with Japanese subtitles. Many films for children are, not surprisingly, dubbed.)

Sunday Study Group: Completely Bilingual

The second prong of attaining biliteracy was a “Sunday School” called Completely Bilingual. As Nobuoka, Isozaki, and Miyake (2015) pointed out, having “a group of their peers” is key. Completely Bilingual was a great boost to Mona’s language development. This was a group founded by three international couples in Kyoto. The group rented space at a Woman’s Center in the city, hired teachers, bought educational materials from the United States, and met every Sunday for one hour during the school year. The classes were set roughly based upon school grade level. Mona attended from approximately age four until the end of elementary school, at age 12, at which point the students “graduate” from the program.

Here Mona learned phonics, spelling, and reading. The students completed short homework assignments every week. By the time she had finished the program, she was for all intents and purposes an independent reader – in both Japanese and English.

Scholastic Book Club

A mother in Completely Bilingual group was a member of the Scholastic Book Club (currently called Scholastic Reading Club). Other families took advantage of this access and placed monthly orders for their children to encourage extensive reading outside of class. Mona received four catalogs (SeeSaw for Grades K-1, Lucky for Grades 2-3, and Arrow for Grades 4-6, TAB for Grades 7 and up) every month and happily circled the books she would like to read. Her mother examined what Mona had marked and ordered most of the selected items although some censorship came into play. When the books arrived, Mona buried her nose in books for hours and read one after another and another until she finished most or all of them.

Extensive Reading in Japanese

Mona’s elementary school also encouraged reading. Every morning children had a “morning reading time” for 10-15 minutes. Students chose a book from the class library or read a book they brought. They were given a reading record booklet to note the books they had read. When they reached 100 books, students went to the principal’s office and received a certificate and a paper medal. This way, Mona kept reading in both English and Japanese. As Cummins (1991) noted, there is an “interdependence of first- and second-language proficiency in bilingual children” – which was apparent in Mona.

Extensive Reading Marathon

When her mother initiated extensive reading at her university, she encouraged Mona to join. Mona started keeping reading records when she was 7. Although she had learned to spell English words by then, she needed help writing necessary information at first. Eventually she became autonomous and kept records quite diligently for the next 4 years. By the time she turned 11, however, she grew tired of recording the books she read, and she stopped keeping track. Although her reading records may not be totally accurate or consistent, it is worthwhile to see how she has developed her English literacy by analyzing her reading records.

Data Analysis

Table 1 shows the total word count, the number of books, and the average length of books that Mona read each year from 2nd grade to 5th grade.

Table 1: Books Read by Grade

| Grade(Age) | 2nd(7-8) | 3rd(8-9) | 4th(9-10) | 5th(10-11) |

| Total Word Count | 1,843,075 | 1,798,009 | 3,538,427 | 2,811,838 |

| Number of Books | 142 | 66 | 91 | 74 |

| Average | 13,356 | 27,243 | 38,884 | 37,998 |

Figure 1 indicates the number of books she read by the length. When she was in 2nd grade, most of the books she read were less than 10,000 words, but when she was in 4th grade, the majority of the books she read fell into the “20,000-49,999” category.

Grade 2

The most read series was Oxford Reading Tree (27 titles), followed by Magic Tree House (15 titles). She also read the whole set of A Series of Unfortunate Events. Other series included I Can Read, Geronimo Stilton, Captain under Pants, Oxford Bookworms (Levels 2-3), Penguin Readers (Levels 2-3), My Father’s Dragon series, Nancy Drew, and Scholastic Reader (Level 3). She also started reading The Little House on the Prairie series. In addition to series, she read Flat Stanley, Dear Dumb Diary, From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler, Number the Stars, and The Diary of a Young Girl.

Grade 3

Mona became infatuated with Nancy Drew and Hardy Boys at this stage and read 12 volumes in total. She also read 8 Princess Diary books. Others were Hannah Montana (4), English Roses (4), Charm Club (4), Rainbow Magic (3), In Their Own Words (3), The Dark Materials (2), How I Survived Middle School (2), and Magic Tree House (2). In the previous year she discovered non-fiction reading Anne Frank’s diary, and she continued to read serious themes this year such as Witness (a story of racial discrimination perpetrated by the KKK), Four Perfect Pebbles (the Holocaust), and Code Talker (about American Indians during WWII) in addition to a variety of other books such as The Cupid Chronicles, Chasing Vermeer, Time Cat, Bad Bad Darlings, and Montmorency and the Assassins. Mona discovered Meg Cabot here.

Grade 4

Mona read A Series of Unfortunate Events for the second time and several new series such as Candy Apple (11), Emily Windsnap (5), Rainbow Magic (4), The Uglies (3), Dear Dumb Diary (3), Eddie Dickens Trilogy (2), Melanie Martin (2), Twilight Saga (2), and Kiki Strike (2). Other titles included Eggs, Bound, Fairest, The Boy in the Striped Pajamas, The Tales of Beedle the Bard, Pollyanna, Corby Flood, The Mysterious Benedict Society, Before Midnight: A Retelling of “Cinderella,” and Airhead. She started reading not only Meg Cabot but also Stephenie Meyer. Apparently she had entered an adolescent female stage here.

Grade 5

She reread the full set of A Series of Unfortunate Events for the third time. Other series she read were: I Can Read (9), Sisters Grimm (5), The Gemma Doyle Trilogy (3), The Clique (3), Geronimo Stilton (2), The Book of Time (2), Little Darlings (2), and Flat Stanley (2). She also read The Book Thief, Stuart Little, The Legend of Spud Murphy, Princess Protection Program, The Secret School, Green Angel, Shakespeare’s Secret, My Life in Pink & Green, Ways to Live Forever, Cornelia and the Audacious Escapades of the Somerset Sisters, The Cupcake Queen, and The Sweet Far Thing. She enjoyed a variety of themes both funny and serious and read a lot of adolescent female novels as well.

Thus, she simply kept reading and reading. How far did she get?

English Proficiency

Her “formal” English education began when she entered public junior high school. In a sense, she “re-learned” the alphabet in the Japanese way; however, it became obvious that she had learned more from books than she would from public school English education. The school encouraged students to take an English proficiency test called EIKEN, and Mona agreed to do so. She passed Grade 2 test (equivalent to TOEIC® 500-640; TOEFL iBT 56-68) at the age of 13, Grade Pre-1 test (equivalent to TOEIC® 740-840: TOEFL iBT 80-97), and Grade 1 test (equivalent to TOEIC® 900-960; TOEFL iBT 104-110) by the time she graduated from junior high school at the age of 15. She didn’t prepare except for a bit of speech practice before the Grade 1 interview test and made “an educated guess” whenever necessary. Apparently her background knowledge and a wide range of passive vocabulary – acquired from books – made it possible.

Discussion

Smith (1994) has argued for beginning teaching – that is, having children begin learning – in a second language after elementary school has begun. Others, like Noguchi (1996b), say, no, the reality of Japanese elementary school and its homework load demands beginning earlier. Mona started early – before elementary school – and it worked. As Noguchi (1996b) notes, English in Japan is highly valorized. From a very early age, like other bilingual/biliterate children Mona was envied for her proficiency in English. The positive image toward English no doubt motivated her to use the language as well.

The cultural environment Mona enjoyed was a household in which two languages were used freely, in which there were many books and reading materials in both languages, and supportive grandparents. The language used at home was flexible: somewhere between the “one parent-one language” strategy and the home/community language strategy. Mona spoke whichever language she felt like speaking and read in whichever language she felt like reading, or more precisely, in whichever language that was available at that time. Moreover, the parents were flexible in their approach in teaching. At the very beginning, Mona and her father worked through phonics books. In addition, they read aloud (see above). In addition to phonics and decoding, they tried to keep the process as enjoyable and “natural” as possible.

Parents, however, do not always make the most patient or best of teachers. Mona and her father worked together for a year or so from age 3-4, and then to both of their relief they discovered the reading/writing program in Kyoto called Completely Bilingual. Mona enjoyed learning in a classroom setting with other children and started working on her homework more seriously. Having an hour-long weekly class may not have been sufficient linguistically, but it turned out to have another important aspect. Like Mona, most of the children were from bicultural families, and meeting them regularly had a positive effect on Mona’s identity. They often shared cultural events such as egg-hunting on Easter and trick-or-treating on Halloween. The interaction with other children and their families in and outside of class undoubtedly helped enhance Mona’s self-image as a prospective bilingual/billiterate child.

Mona learned to read quite early, yet even after Mona became an autonomous reader, the parents kept reading to her at night and made sure she always had easy access to books. As the reading records show, she gradually raised her reading (difficulty) level. When she was in second grade, she read many books shorter than 1,000 words, but in fourth grade she read much longer books, between 20,000 and 50,000 words. After she became a 5th grader, she grew tired of keeping reading records. However, she continued reading without keeping records. She enjoyed both fiction and non-fiction, and her choices included various categories such as adventure, romance, mystery, history, biography, and humor. As Noguchi (1996b, p. 35) writes:

One of the best ways to ensure that children learn to read English is to introduce them to the joys of reading at an early age. And the simplest way to teach children the joys of reading is to read good books — books that both you and your children enjoy — to them.

Conclusion

Mona now reads at grade level in two languages, Japanese and English. Her stronger language – both spoken and written – is her native Japanese. However, due to her diligence and her parents’ sometimes hit-or-miss efforts, she reads independently and freely for pleasure in both languages. She does not need a dictionary, and she understands word play and cultural allusions. Aside from some prodding to do the Completely Bilingual homework, she never needed to be badgered into reading in English; it was a natural, normal, “fun” thing to do. She is proof that biliteracy is an attainable goal. One does not need to attend an international school or live abroad. With a willing child and parents, it can be accomplished.

References

Baker, M., Rudd, R., & Pomeroy, C. (2001). Tapping into the creative potential of higher education: A theoretical perspective. Journal of Southern Agricultural Education Research, 51(1), 161-172.

Bialystok, E., Luk, G., & Kwan, E. (2005). Bilingualism, biliteracy, and learning to read: Interactions among languages and writing systems. Scientific Studies of Reading, 9(1), 43-61.

Brown, S. (2001). Raising a miracle child: Part 2. Bilingual Japan, 10(5), 11-13.

Cummins, J. (1991). Interdependence of first- and second-language proficiency in bilingual children. In E. Bialystok (ed.), Language processing in bilingual children (pp. 70 - 89). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Giambo, D.A., & Szecsi, T. (2015). Promoting and maintaining bilingualism and biliteracy: Cognitive and biliteracy benefits & strategies for monolingual teachers. The Open Communication Journal, 9, (Suppl 1: M8) 56-60.

Hakuta, K., & Diaz, R.M. (1985). The relationship between degree of bilingualism and cognitive ability: A critical discussion and some new longitudinal data. In K.E. Nelson (ed.), Children’s Language, 5, 319-344.

Krashen, S. (2004). The power of reading: Insights from the research. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited Inc.

Lüdi, G. (2006). Multilingual repertoires and the consequences for linguistic theory. In K. Bührig & J. D. ten Thije (eds.), Beyond misunderstanding-Linguistic analyses of intercultural communication, 13-58.

Matsuda, S. (2001). Raising a miracle child: Part 1. Bilingual Japan, 10(5), 8-10.

Nobuoka, M., Isozaki, A.H., & Miyake, S.B. (2015). Starting your bilingual child on the path to biliteracy. In J. Ward (ed.), Monographs on Bilingualism, 17.

Noguchi, M.G. (1996a). The bilingual parent as model for the bilingual child. Policy Science, 245-261.

Noguchi, M.G. (1996b). Adding biliteracy to bilingualism. Monographs on Bilingualism, 4, 1-48.

Pavlenko, A. (2009). Emotions and Multilingualism. NY: Cambridge University Press.

Smith, C. (1994). Teaching children to read in the second language. Monographs on Bilingualism, 1, 1-28.

Chapter Three: Project of an Extensive Reading Course for Brazilian Languages and Literature Teachers In-service

Roberta M. Ciocari

University of Passo Fundo, Brazil

Abstract

Reading is a highly complex activity which requires an interaction among many factors, from which we cite the text, the purpose of reading, and the readers themselves. Besides, when we talk about reading in a foreign language, the challenge can become even more difficult. In this work, English, Spanish, Portuguese and Literature teachers from Brazil are the focus. The idea is sharing with them some ideas about the Extensive Reading (ER) approach. Here is the first draft of an ER course designed for them. This approach was chosen because it helps readers increase their vocabulary, their writing, listening, and speaking abilities, and above all, they start to read more fluently, which can lead them to develop a taste for reading and consequently, the habit of reading. ER can also increase their motivation to study more. In Brazil, there is a problem in the education of foreign language teachers: the majority of them do not get enough knowledge of the target language while pursuing their education. However, they have to teach it after graduating, even if they have only a poor language development. Besides, Portuguese teachers often teach only grammar, and the Literature ones, only literary trends, not being themselves good reading models. The point here is to help these teachers develop a reading taste and habit along with autonomy in their learning as well as in their teaching, with the aid of ER, so in the future they can be good reading models for their students.

Introduction

Teacher education should be seen as a process, not as something still or finished, since a teacher is a professional who is always evolving personally as well as professionally. According to García (2013), “it is not intended that initial education offers ‘finished products’. It should be faced as the very first phase of a long and differentiated process of professional development ” (p. 55). This is clearly seen concerning foreign language teachers because of the issue of acquisition of the foreign language they teach. In Brazil, the initial education of these teachers at college is commonly basic. They cannot start teaching intermediate or advanced levels. This only happens as time goes by and they build their proficiency in the foreign language. Concerning Portuguese teachers, they often teach only grammar, and the Literature ones, only literary trends, not being themselves good reading models.

On the other hand, for that teacher who is more experienced, continuing education is necessary to instill enthusiasm in their practice. This enthusiasm can be “described as a predisposition to confront work with curiosity, energy, renewal ability and a wish to fight routine” (Dewey, 1989, p. 44).

It is important to mention the aspect of continuing development that reading encompasses for the teacher:

The core of a teacher’s development is, doubtless, the reading. For them, reading constitutes an instrument and/or a practice, a way of existing. Their fundamental compromise, according to the society expectations, is the (re)production of knowledge and the educational preparation of the new generations. Teacher, a subject who reads, and reading, a professional behavior, are undichotomizable terms – a knot that cannot nor must not untie (Theodoro da Silva, 2009, p. 23).

Moreover, reading must be considered as a way of enchanting the soul. Everyday life imposes to the teacher various kinds of literacy, among them is the one of “continuous and unpretentious acquaintanceship with literary texts and arts in general, to feed fantasy and to build other views of reality” (Theodoro da Silva, 2009, p. 25). Reading cannot be considered only as regarding written texts, but in this work, as a need for delimitation, it is going to be considered as that: Reading of written texts (poems, short stories or longer narratives).

According to Theodoro da Silva (2009), the rushed education of teachers in Brazil, along with precarious work conditions, low salaries and tortuous educational policies are factors that corroborate for teachers carrying out their profession without having a strong basis of a reading education. This situation brings disastrous consequences for the classroom, such as un-updateness of the teacher, “restrict repertoire, absence of reading abilities and competence, intellectual stagnation”, among others mentioned by the author.

Celani (2010, p. 61) specifies more clearly this view regarding languages teachers education: She states that one of the reasons for the unsatisfactory initial education of languages teachers in both theoretical and practical, as well as in linguistic aspects, is the double licentiate/Bachelor of Arts, that links up the foreign language studies with Portuguese studies, making the preparation of the future foreign languages teacher weak. Therefore,

(…) the teaching of foreign languages at school, especially in the public school, will be delivered to teachers who do not have even the basic mastery of the foreign language they are supposed to teach. Additionally, they were not exposed to a minimum theoretical reference; a reflexive education on teaching and on teaching a foreign language was not provided, let alone on teaching in adverse situations. Pre-service education is inadequate and unsatisfactory. Perhaps that explains the reason for the common belief that you do not learn a foreign language at school. With unprepared teachers, of course, you do not.

The question is: How to implement continuing education actions that are seen as relevant for the teachers and that can influence positively their classes? The extensive reading approach is considered one of the possible ways to make the continuous education of teachers a personally and professionally meaningful experience, improving their lives and consequently, their way of teaching. According to Day and Bamford (2002), “extensive reading, apart from its impact on language and reading ability, can be a key to unlocking the all important taste for foreign language reading among students.”

The general purpose here is to encourage those teachers to become teachers who read, with the accompanying influence on their students. It aims at building a more autonomous teacher profile since

(…) the good teacher is the one who is able to articulate, in their pedagogical work two basic instances: Theory (elaborate knowledge) and practice (action) so as to overcome a technical thinking of application and to take over an attitude of intelligent and creative reflection (Fávero; Tonieto, 2010, p. 63).

With the aim of clarifying what reading is, it is also important to have in mind the contribution of the literary understanding for the intellectual and human development (Langer, 2005, p. 7): “literary imagination (…) is a productive way of human reasoning which is useful not only at school, but also at work and in the daily life.”

According to Langer, when we read a book, we start a process called “envisionment building”. This process represents “the world of conceptualization a person has in a certain moment [of the reading]” (p. 22). It is different for each person and “includes what the person understands and does not understand, as well as any momentaneous suppositions about how the whole textual world will reveal, and any reactions to this” (p. 23). She states that “while we are reading, the envisionment buildings change; some ideas lose importance, others are added, and some are reinterpreted” (p. 24). Even after the book had been closed, the reader can still change some envisionments through additional thoughts, writings, and other readings or from discussions in the classroom. This process is highly social since it involves the intertextual web of history and experience which Bakhtin (1981) talks about: texts, subtexts, pretexts from past, the answers from the reader in the moment of the reading and the texts that will be generated or met in the future (as cited in Langer, 2005, p. 31). That is why, in this research, extensive reading is going to be faced as the basis for a broader discussion, because besides improving the readers fluency in reading, speaking, writing, in vocabulary acquisition, and even in listening, ER is going to be the fertile soil where the texts can seed ideas in students’ minds, and the teacher can help them harvest a better understanding of the world.

But what is extensive reading, exactly? According to Day (2003), “Extensive reading is based on the well-established premise that we learn to read by reading”. In this approach, reading is not seen as a simple ability or as translation of texts. Readers read having in mind the aim of reaching a general understanding and also to get information and pleasure. Readers can also be challenged to expand their comfort zone and read more demanding materials. This author, along with Bamford (1998, p. 7), cites the 10 basic principles of this approach:

- Students read as much as possible.

- A varied of materials on a wide range of topics is available.

- Students select what they want to read.

- The purposes of reading are usually related to pleasure, information, and general understanding.

- Reading is its own reward.

- Reading materials are well within the linguistic competence of the students.

- Reading is individual and silent.

- Reading speed is usually faster rather than slower.

- Teachers orient students to the goals of the program.

- The teacher is a role model of a reader for students.

All these characteristics are important for developing a program in extensive reading, but due to certain peculiarities on the application of the approach to languages and literature teachers in Brazil, it is believed that some of them must be analyzed more deeply and, if necessary, rethought for a better result of the actions of this research, since ER is considered an approach, not only a method or technique: “The principles are best viewed as guidelines, not as commandments” (Macalister, 2015, p. 123).

Method

This study aims at:

- Proposing and applying a course of continuous education on ER for teachers of languages and literature from >public and private schools in Passo Fundo, RS, Brazil

- Investigating the validity of this course for the Brazilian teachers.

The participants of this research are going to be Brazilian teachers of languages (Portuguese, English and Spanish) and literature from elementary and secondary schools, who enroll themselves in the Sensu Latu Specialization course at IFSul Passo Fundo Campus next year (2016). Twenty applicants are going to be selected to take part of the subject called “Extensive Reading: Theory and Practice.”

To achieve the objectives mentioned above, an action research is going to be performed with the teacher-students (The teachers who are students in the course; the author will be identified as the teacher-researcher). This kind of research consists of people in action in a certain social practice and at the same time, investigating this very practice (Moita Lopes, 1996, p. 185). This action research is going to be qualitative and ethnographic, without working with categories previously established. It is going to use instruments such as diaries, questionnaires, interviews, recordings (audio and/or video), and notes from the teacher with the aim of >(…) trying to discover: a) what is happening in this context; b) how these events >are organized; c) what they mean for students and teachers; and d) how these organizations can compare with >organizations in other learning environments (Erickson, 1986).

The recordings are probably going to be made using the software called CLASS, a Windows laptop computer system for the in-class analysis of classroom discourse, by professor Martin Nystrand (2002).

For this research, the first draft of a learning plan (see the appendix) was elaborated having as its base theoretical and practical studies about extensive reading. The subject of ER is going to be allotted 30 hours distributed over four Saturdays. The classes are going to be in the morning and in the afternoon, from 8 am to 12 pm, and from 1:30 pm to 5:30 pm, with breaks for coffee (about 20 min) and lunch (1h30min). The ER classes are planned to take place in June, 2016. Previously, a questionnaire is going to be applied for the teacher-students, probably in March, so as to gather information about them, such as reading habits in the mother tongue and/or a foreign language, previous education, professional experience, etc. The main objective of this discipline is to introduce the extensive reading approach for the teacher-students. Also, there are going to be demonstrations, practice and reflections on possible methodologies and techniques to be applied with their students having in mind this approach and the reality of their schools. A post questionnaire is planned to be applied about six months after the classes to measure the impact of the ER approach on the participants.

On the first meeting, after the usual introductions, the teacher-researcher is going to explain the ER approach briefly, and the way the discipline is organized. Then, the results of the previously applied questionnaire are going to be made available for everybody, without mentioning any names of respondents. The materials (books, photocopies, etc) are going to be distributed. After that, the idea is to divide them in small groups of three or four and assign a small article on ER for each group to read, discuss and present to the class. The teacher-researcher thought of the articles by Day on Teacher Talk Journal. Now, the first problem arises: the teacher-students may not have a good fluency in reading texts in English, even the English teachers. It would be counterproductive to oblige them read scientific texts in English, and it would totally go against the objectives of this work. One of the solutions is the teacher to previously translate the articles into Portuguese. Another solution could be to work with more generic texts about reading using texts which are already written in Portuguese. Or maybe, the teacher can find texts about ER written in Portuguese, which would be the ideal solution. Even articles in Spanish would be fine.

After the coffee break, an activity called “From Concrete Poetry to Sonnets and Back to the Future,” made by the teacher-researcher, is going to be performed. This activity comprises some Concrete poetry, some poems by Shel Silverstein, Emily Dickinson, and Robert Frost (in English), and also some digital poetry (in Portuguese). After presenting some information about the writers, we are going to read them together for the meaning, without stopping at each unknown word. The aim is to apprehend the essence of the selected poems and to feel their beauty. This is going to be the first time the teacher-students are going to be building envisionments. Alternatively, according the level of proficiency of the students, the poetry can be presented in Portuguese and/or in Spanish.

After the lunch break, we are going to carry out an activity with the previously read poetry and the use of double-entry journals so the teacher-students can note their thoughts and impressions about the poetry.

In the final part of the class, we are going to read and listen to a reader in English called The Locked Room, by Peter Viney. After that, we are going to play a card game. The reader can also be in Spanish, too. Some minutes are going to be reserved to DEAR (Drop Everything and Read) with texts of their preference (according to their answers to the questionnaire applied previously and the possibilities of the research). Then the homework is going to be explained: They are going to read a chapter or two of the book The Giver. The ones who cannot read in English are going to read it in Spanish or in Portuguese. This reading is going to be needed for the literature circles that are going to start next class, so they are going to get their roles now, too. Besides, some texts on ER are going to be assigned as homework to be read, and presented next class for the group. Again, the problem of the language of the articles is going to be an issue to be solved.

On the second Saturday, we are going to start discussing the articles on ER, which were read for homework. After that, we are going to read a short story (or two) and use graphic organizers, which is a new technique for the majority of Brazilian teachers. After the lunch break, our first literature circle is going to take place. The chapters and the roles for the next literature circle are going to be assigned then. After the coffee break, we are going to the lab to enter and examine some sites on ER. We either can talk about their impressions on the sites on ER so far, and/or the teacher can apply a questionnaire for them or can interview them in private. This still has to be decided.

On the third Saturday, we are going to start with different graphic organizers, this time, for the chapters read of The Giver, with the help of the e-board. Right after that activity, the teacher-students are going to be invited to write a letter or imagine a present to give one of the characters of the book. After the break, the second literature circle is going to take place. After lunch, the teacher-students are going to surf mreader and get to know the advantages it offers as an on-line resource for ER. Again, some time is going to be reserved for Sustained Silent Reading, and an activity which brings their ideas about ER is going to be planned.

On the last Saturday, we are going to start with our last literature circle. After that, an activity in the site Story Bird is going to be proposed. It is also important to give space for creative production, too. They can produce stories in English, Spanish or Portuguese using the resources this site offers. Their last reflections on ER are going to be taken. After the lunch break, their final work is going to be explained: They are going to write a small article to be submitted to a Brazilian journal called Bem Legal. They are going to choose some articles to read (they are in Portuguese) to see their structure. Then, after the second break, we are going to watch the movie The Giver and discuss the differences, comparing it with the book.

Since the research is going to happen only in the future, there are no results or discussions available now.

The participation in this congress was supported by the Extensive Reading Foundation scholarship awarded to Roberta M. Ciocari.

References

Bakhtin, M. (1981). Marxismo e filosofia da linguagem, 7th ed. São Paulo, SP: Hucitec.

Bridges, J. (producer), & Noice, P. (director). (2014). The Giver [Motion picture]. United States: Weistein Company.

Celani, M. A. A. (2010). Perguntas ainda sem resposta na formação de professores de línguas. In: Gimenes, T. & Monteiro, M. C. G., Formação de professores de línguas na America Latina e transformação social. Campinas, SP: Pontes Editores.

Day, R. R. (2003). Teaching Reading: An Extensive Reading Approach. Teacher Talk, 20. Retrieved from http://www.cape.edu/docs/TTalk0020.pdf

Day, R. R., & Bamford, J. (1998). Extensive reading in the second language classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Day, R. R.; Bamford, J. (2002). Top ten principles for teaching extensive reading. Reading in a Foreign Language, 14(2).

Dewey, J. (1989). Como Pensamos. Barcelona: Paidós.

Dickinson, E. (2012). I am nobody! Who are you? Poems by Emily Dickinson. New York, NY: Scholastic Inc., 2012.

Erickson, F. (1986). Qualitative methods in research on teaching. In Wittrock, M. (org.) Handbook of research on teaching. New York, NY: MacMillan.

Fávero, A. A., & Tonieto, C. (2010). Educar o educador: reflexões sobre a formação docente. Campinas, SP: Mercado de Letras.

Frost, R. (1928). West Running Brook. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company.

García, C. M. (2013). Formação de professores. Porto: Porto Editora.

Langer, J. (2005). Envisioning literature. Passo Fundo, RS: Ed. Universidade de Passo Fundo.

Lowry, L. (1993). The Giver. New York, NY: Laurel-Leaf.

Macalister, J. (2015). Guidelines or commandments? Reconsidering core principles in extensive reading. Reading in a Foreign Language, 27(1), 112-128.

Moita Lopes, L. P. (1996). Oficina de linguística aplicada. Campinas, SP: Mercado de Letras.

Nystrand, M. (2002, April). CLASS. Retrieved from http://english.wisc.edu/nystrand/classdownload.html

Silverstein, S. (1981). A Light in the Attic. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers.

Theodoro da Silva, E. (2009) O professor leitor. In Rosing, Tânia et al (Orgs.) Mediação de leitura: Discussões e alternativas para a formação de leitores. São Paulo, SP: Global.

Viney, P. (2000). The Locked Room. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Appendix

Sensu Latu Specialization

Subject: Extensive Reading: Theory and Practice – 30h – Saturdays: mornings and afternoons – first semester of 2016, probably in June

Subject target: Brazilian teachers of Portuguese, English, Spanish, and Literature of elementary and high school, and interested people

Syllabus: Introduction to the Extensive Reading approach. Demonstration, practice and reflection on possible methodologies and techniques to be applied with students having in mind this approach.

Content/activities:

Saturday 1

• 1h: Teacher and students introduction; introduction of the ER approach; explanation about the subject; discussion of the results of the previous applied questionnaire; material distribution

• 1h: Reading and discussion of some articles on ER from English Teacher Talk (Hawaii) / or other material in Portuguese or Spanish

Coffee break

• 1h: Activity: From Concrete Poetry to Sonnets and Back to the Future.

• 1h: Activity: From Concrete Poetry to Sonnets and Back to the Future.

LUNCH BREAK

• 1h: Poetry activity: Double-Entry Journal

• 1h: Poetry activity: Double-Entry Journal

Coffee break

• 1h: Activity: The Locked Room + game

• 1h: Activity: DEAR (Drop Everything and Read) with readers and other books or texts (according to students’ tastes). Homework: literature circles with The Giver / O doador de memórias (Portuguese) / El doador de memorias (Spanish); articles on ER to read for homework and present next class.

Saturday 2

• Presentation and discussion of articles

• Presentation and discussion of articles

Coffee break

• Short stories activity: graphic organizers

• Short stories activity: graphic organizers

LUNCH BREAK

• 1st literature circle

• 1st literature circle; homework

Coffee break

• Sites for ER activities: http://www.er-central.com/library/; http://beeoasis.com/;http:/ learningenglish.voanews.com/; http://www.nlm.nih.gov/

• Reflections on ER

Saturday 3

• Graphic Organizers in the e-board: The Giver

• Drawing a gift for one of the characters, explain why and/or writing a letter

Coffee break

• 2nd literature circle

• 2nd literature circle; homework

LUNCH BREAK

• Moodle Reader / mreader

• Moodle Reader / mreader

Coffee break

• Sustained Silent Reading

• Reflections on ER

Saturday 4

• 3rd literature circle: The Giver

• 3rd literature circle: The Giver

Coffee break

• Site: Storybird

• Reflections on ER

LUNCH BREAK

• Explanation of final work: enter the site of Bem Legal Journal. Choose an article, read it and present it to the group. Write (for homework) an article explaining how you would use the ER approach with your students in your context.

• Continuation of previous activity.

Coffee break

• Movie: The Giver + discussion

• Movie: The Giver + discussion / farewell

Chapter Four: Longitudinal Case Study of a 7-year Long ER Program

Hitoshi Nishizawa & Takayoshi Yoshioka

National Institute of Technology, Toyota College, Japan

Abstract

The duration of an ER program is an influential factor in EFL settings because, after the initial excitement, elementary EFL learners in ER programs seem to face a challenging period when they struggle to feel improvement before they start to read autonomously. The programs fail to satisfy their students if they end during this period. Therefore, it has practical value to examine how students read and feel in an ER program of long duration.

In this study, we ran a 7-year long ER program at a technical college in Japan, where students were elementary EFL learners when they joined the program. The program has a 45-minute weekly Sustained Silent Reading (SSR) lesson for 30 weeks per year, and 14 students completed the 7-year program. In the program, the average student recognized that he could actually read English texts without translation, increased his scores in standardized tests such as TOEIC, and came to read confidently until the end of the program.

The longitudinal study also revealed the influence of the amount to be read and readability levels of English texts. A million words were confirmed as a valuable milestone for the amount to be read. Reading picture books with high comprehension before stating to read Graded Readers (GR) was an effective practice to overcome the translating habit of Japanese elementary EFL learners, and the amount of reading easy-to-read books especially in early years had a strong influence on how the students improve their English proficiency.

Background

Japanese EFL learners’ English proficiency is generally low as is shown in score distribution of the Test of English for International Communication (TOEIC). The TOEIC is a standardized proficiency test of receptive English skills for nonnative speakers of English (Woodford, 1982) widely used in Japan. The institutional program of TOEIC had 1.26 million test takers in 2013 academic year (IIBC, 2014: 5), where 62% belonged to beginner or elementary levels (10 - 490) and 31% stayed in lower-intermediate level (495 - 740). University students’ average scores except language majors also belonged to the elementary level.

Effect of ER Measured with Standardized Tests

ER was an approach rarely practiced in Japanese English education, partly because the benefits of ER had not been shown quantitatively. Even though Gradman and Hanania (1991) reported university ESL students’ TOFEL scores were most strongly correlated with extra-curricular reading among 44 language-learning factors, it obviously required a large amount of reading and long duration. Japanese teachers and learners were wondering if the benefits were large enough for them to alter the current teaching/learning practices. They wanted to know the effect in scores on high-stake examinations or standardized tests.

There were several studies, where the benefit of ER was measured with standardized tests. For example, Mason (2004) evaluated the effect with reading section of TOEIC. 104 Japanese college students major in English had read about 500,000 words in three semesters (1.5 years). 88 students’ TOEIC/Reading scores were measured as pretest and posttest, and the average was 121 and 157 respectively. If we assume the same score ratio of reading part and total score: 0.446 (123.64/277.26) was kept, their TOEIC total score was estimated to be 272 and 353 respectively (increase rate was 0.162 point / a thousand words). The score of the posttest, however, remained still in elementary level, and a half million words may not be large enough.

Amount to be Read and Duration of ER Programs

Sakai (2002) had proposed one million total words as a milestone for ER in Japanese EFL settings based on the experience of his ER program for university engineering majors. A million words was about eight to ten times of the total words read by the university students in Robb and Susser’s ER project (1989) who had read 641 pages in average.

There were a few ER programs in which students actually read the amount close to a million words. Furukawa (2011) reported the average total words were 1.2 million words by 12th graders staying in the sixth-year form of his ER program. Kanda (2009) studied the ER of a university student for three years, who had read a million words. Either program needed longer duration.

Readability of English Texts

Another important aspect for ER in EFL settings is the readability of English texts. Sakai (2002) proposed Japanese EFL learners to start ER from leveled readers, such as I Can Read Books Level 1 (ICR1), series of picture books designed to invite L1 children to reading. They were easier books than the starter-level of GR. Furukawa et al (2005) recognized the impact of Sakai’s (2002) proposal, and compiled a book-list for Japanese EFL learners including the Oxford Reading Tree series (ORT), Foundations Reading Library series (FRL), and starter levels of GR. They also defined the Yomiyasusa level (YL), a readability scale optimized for Japanese EFL learners. The scale is partially based on objective measures such as headwords, grammatical complexity, or length, but also on subjective measures such as how easy typical students find the story (Eichhorst & Sheron, 2013: 8). They were guided by the recognition “Even if a student knows all the words of a text in their decontextualized forms, it is still possible that the student may not comprehend that text” as McLean (2014) stated.

In their ER program guided by Sakai’s (2002) advice and using the booklist of Furukawa et al (2005), Nishizawa and Yoshioka (2011) observed that students in their ER program were reading GR of headwords fewer than 600. The GR were far easier books than the standard books for ER in ESL settings, edited by Edinburgh Project on Extensive Reading (EPER) (Hill, 1997, cited in Day & Bamford, 1998: 173-212). They argued that Oxford Bookworms Stage 1 (400 headwords) was a standard book-series read by their students whose TOEIC scores were 450 in their program and it was too difficult for elementary EFL learners to read extensively with sufficient comprehension.

Takase (2008) showed the positive effect of reading an average of over 100 very easy-to-read books (YL 0.0 – 1.0) at the beginning of her ER program on Japanese university students. Furukawa (2011) suggested that Japanese EFL learners should read at least 100 thousand words before finishing YL 1.0 (Oxford Reading Tree Stage 9), which was as easy as Takase’s easy-to-read books (2008).

Research Questions

We would like to answer the following three questions in this study. The first question is “Is a million words a valuable milestone for elementary EFL learners?” and the second is “How many years does an ER program need to accomplish it?” We need to improve the students’ English proficiency from elementary level (TOEIC 408): 7th year kosen students (IIBC, 2014: 7) to lower-intermediate level (TOEIC 565): the expected level for newly employed university graduates (IIBC, 2014: 23). We would like to know if seven years is long enough for our students to read a million words when we add one 45-minute weekly ER lesson to traditional English classes.

The third question is “Is it necessary for elementary EFL learners to start their ER from picture books or starter level of GR?” The effect of reading those easy-to-read books must be evaluated by the students’ proficiency improvement in a long-term program.

Method

Subjects and English lessons

The ER program was conducted at a college of technology or kosen that was a specialized institution for early engineering education in Japan. Each of the five departments had a 5-year foundation course (class size from 1st to 5th year was 40 students each) and a 2-year advanced course (class size for 6th and 7th year was 4 students each). Kosen accepted graduates from junior high schools, where they had already learnt English for three years. Fresh kosen students were generally excellent in mathematics and science, but moderate or average grade in English skills. From 10 to 20 % of graduates from foundation course, whose English skills were in the middle range of the class, proceeded to the advanced course.

The subjects of this study were five students (Student A - E) who had entered a kosen in 2006 and nine students (Student F - N) who entered in 2007. They were the seventh year students in 2012 and 2013, and the groups were called as 2012 cohort and 2013 cohort in this study. The students who had studied abroad or stayed in the course shorter or longer than seven years were excluded from this study.

Their English education consisted of traditional lessons basically taught with the grammar/translation method and ER. English classes for the first year were three 90-minute weekly lessons for 30 weeks, in which 30 minutes a week were assigned to ER other than traditional lessons (Table 1).

Table 1. Lesson Units per week for Traditional Lessons and ER

| Year | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | 6th | 7th | Total | |

| Traditional | 5.3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 + 1 | 2 | 1 + 0 | 23.3 (78%) | |

| ER | 0.7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6.7 (22%) |

*one unit is a 45-minute weekly lesson for 30 weeks or a 90-minute weekly lesson for 15 weeks

Traditional English classes continued as two 90-minute lessons from the second year to the first half of the fifth year, and a class from the second half of the fifth year to the first half of the seventh year. In-class ER was conducted as a 45-minute weekly lesson from the second year to the seventh year. 150 hours (22% of total 30 units) were assigned to in-class ER during the seven years.

ER activities

Main ER activity was sustained silent reading (SSR), plus some shadowing, and reading while listening. Shadowing was conducted mostly at the first year for the students to familiarize English sound. Reading while listening (LR) was a practice to read English texts along with listening to audio narration of the text. The readers were not supposed to interrupt the narration and were force to read the text at the same speed of the narration. They comprehended the story mainly from the texts but not from the narration. The narration set the reading pace, and was expected to protect the students from their habit to translate English texts into Japanese. It made a good introduction to ER. Around 30% of the students did LR in average, but in turn.

Reading Log All the students had recorded their reading histories in and out of class in their logbooks, which were periodically reviewed by the teachers. The record contained the date, title, series name, YL, word count of the book, cumulated word count, five-graded subjective evaluation of the story, and a short comment describing how the students thought about the story or how they felt about their reading. After the program had finished, available earlier logbooks of six students (D, G, H, I, J, L) were analyzed thoroughly to examine how they had read the first 400,000 words. All the books were categorized by YL and the YL-layered word count were summed.

Evaluation and Analysis We used the total score of TOEIC tests to evaluate English proficiency of the subjects because the test had high reliability and was sensible to English skills of elementary and intermediate levels, and both scores of the reading section and listening section of TOEIC increased in balance in the past studies (e.g., Nishizawa, Yoshioka & Fukada, 2010). The students took from 7 to 16 TOEIC tests in the program from their second to seventh years. Because the date and total word count at the tests were recorded in students’ reading logs, we could analyze the relation of total word count and TOEIC score to estimate the necessary total words to achieve TOEIC 400.

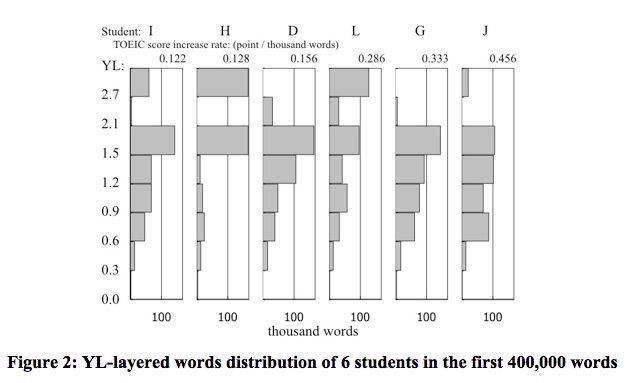

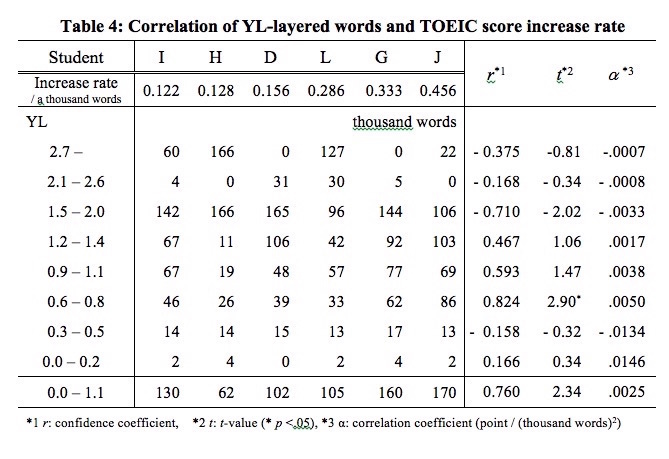

We also analyzed the effect of YL-layered word count in their first 400,000 words upon the TOEIC score increase rates of six students to know the influence of reading easy-to-read books at the start of the ER program.

Finally, we gave the nine students in 2013 cohort a questionnaire to ask two questions: 1) When they felt that they could read English texts fluently; 2) When they felt that they could avoid Japanese in reading English texts. The questionnaire requested the students to describe “when” as a small circle on the 21-centimeter scale (3 centimeters per year), so we could know “when” in one decimal place, for example 4.6 years.

Results

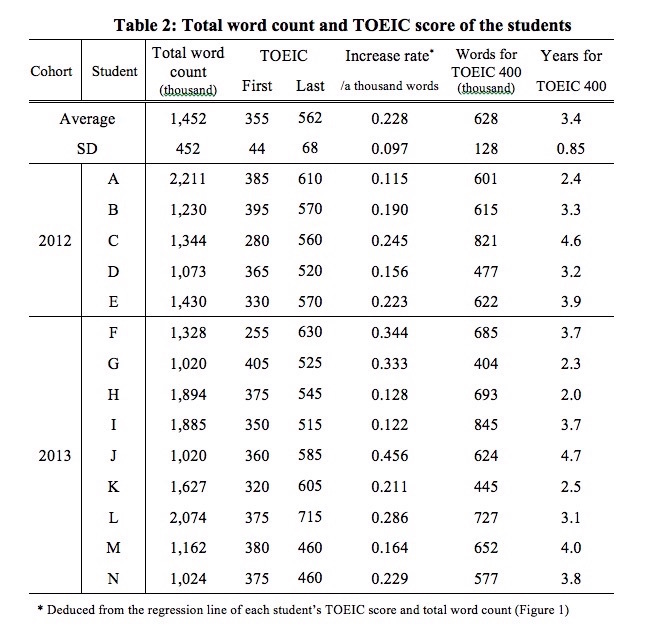

Average total words read by 14 students were 1,452,000 words, and all the students had read at least a million words during the seven years (Table 2). As the result, average TOEIC score increased to 562 with the lowest score of 460, which was a little lower than the border of elementary/lower-intermediate levels (470).

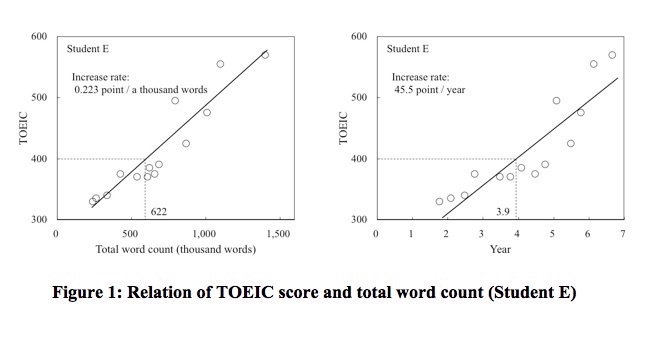

Because the students took from 7 to 16 TOEIC tests during their stay in the program, we could analyze the relation of TOEIC score depending on the total word count (Figure 1).

The student’s TOEIC score increased with the average rate of 0.228 point / a thousand words with a standard deviation of 0.097. The increase rate had a wide variety from the lowest 0.115 to the highest 0.456.

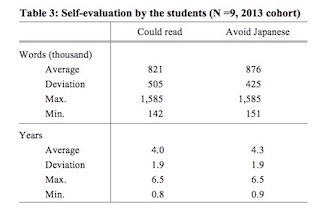

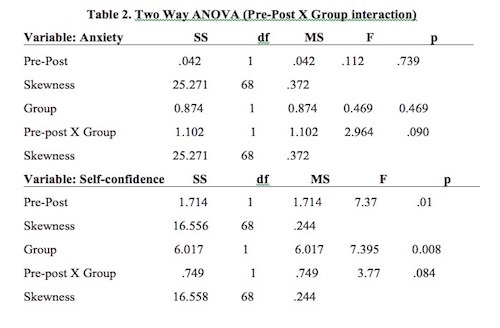

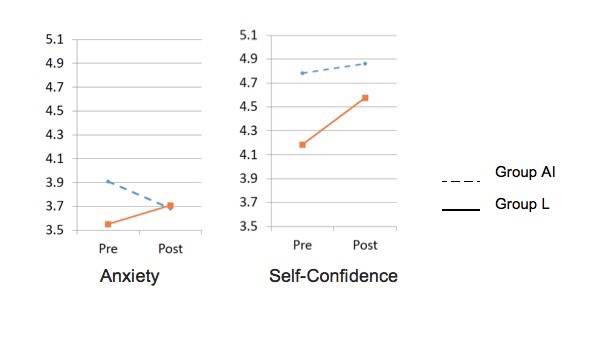

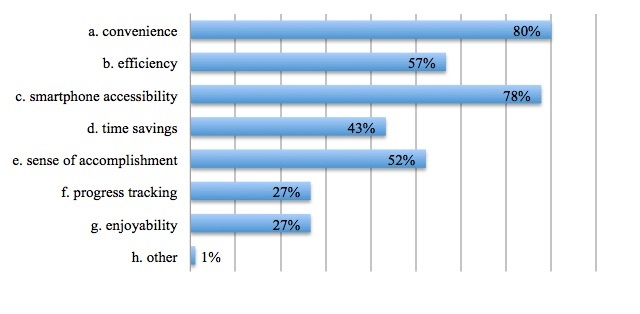

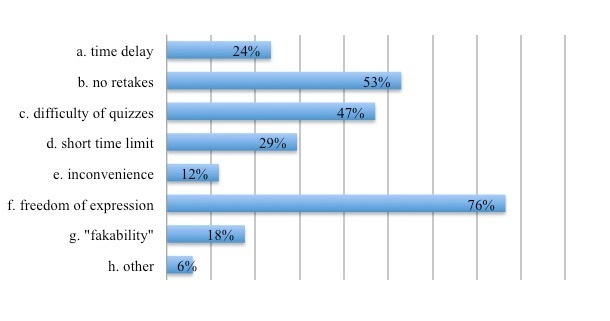

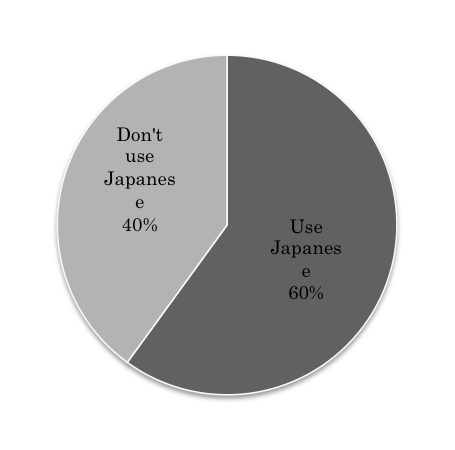

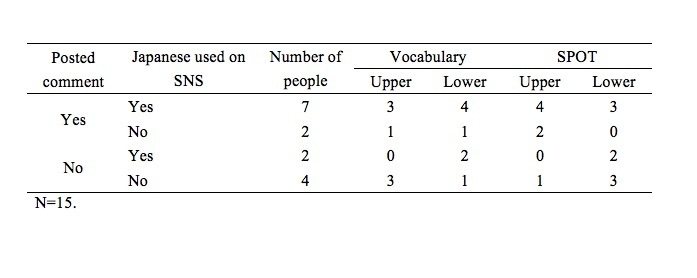

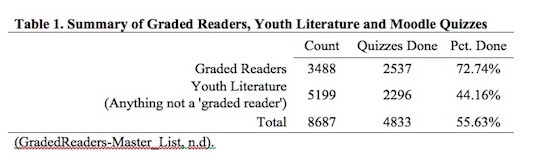

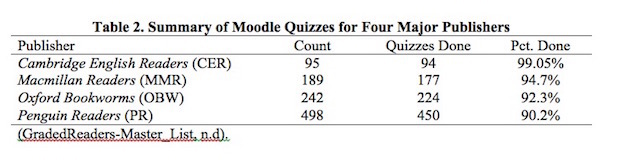

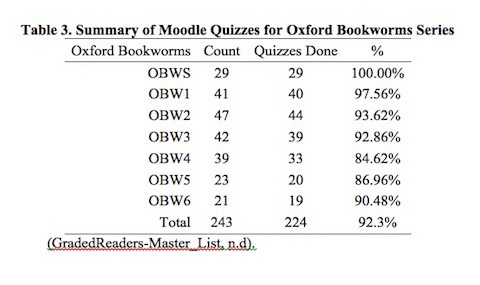

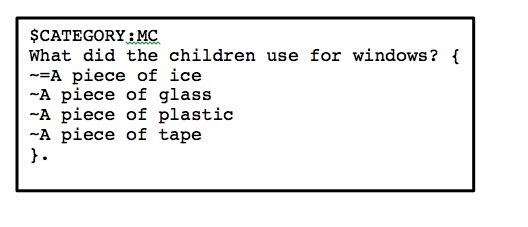

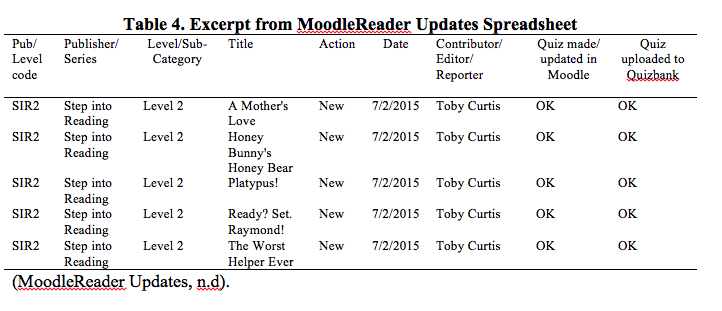

The necessary total word count to achieve TOEIC 400, which was calculated from the regression line of each student’s TOEIC score and total word count as shown in Figure 1, was 628,000 words in average, and the slowest learner needed to read 845,000 words to exceed TOEIC 400. Necessary years to achieve TOEIC 400, which was calculated from the regression line of each student’s TOEIC score versus years in the ER program, was 3.4 years in average, and the slowest learner need to stay 4.7 years to exceed TOEIC 400.