Table of Contents

Sampler edition of ‘The Dowser’s Workbook’

by Tom Graves

This sampler-edition ebook of The Dowser’s Workbook is based on the third edition of the book, as published by Tetradian Books in 2008. Chapters highlighted in bold are included in this sampler-edition.

- 1: Using this book

- 2: A practical introduction

- 3: Make yourself comfortable

- 4: The pendulum

- 5: The dowser’s toolkit

- 6: Putting it to use

- 7: “Physician, know thyself”

- 8: Finding out

- 9: The greater toolkit

- 10: So how does it work?

- 11: A test of skill

- Appendix

The Dowser’s Workbook

Understanding and using the power of dowsing

Tom Graves

This ebook edition published April 2014

based on the third edition published May 2008 by

Tetradian Books

Unit 215, Communications House

9 St Johns Street, Colchester, Essex CO2 7NN

England

http://www.tetradianbooks.com

Originally published in 1989 by Aquarian Press, Wellingborough, England

Second edition published in 1993 as Discover Dowsing by Aquarian Press

ISBN 978-1-906681-06-7 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-906681-07-4 (e-book)

© Tom Graves 1989, 2008, 2014

The right of Tom Graves to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Text illustrations by Tom Graves and Maja Evans

Cover illustration derived from a wood-engraving in the Dover collection.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher and the authors. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade be otherwise lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published.

Contents

- 1: Using this book

- 2: A practical introduction

- 3: Make yourself comfortable

- 4: The pendulum

- 5: The dowser’s toolkit

- 6: Putting it to use

- 7: “Physician, know thyself”

- 8: Finding out

- 9: The greater toolkit

- 10: So how does it work?

- 11: A test of skill

- Appendix

1: Using this book

Dowsing is a way of using your body’s own reflexes to help you interpret the world around you: to find things, to make sense of things, to develop new ways of looking and seeing. And, as the title suggests, this is a _work_book on dowsing: so it’s a practical book, with a series of exercises that bring the ideas behind dowsing into a practical, usable context. By using the book in this way, working through each of the exercises in sequence rather than just reading them, you should be able to develop new dowsing skills, or to improve the skills you already have.

What we learn to do in dowsing is take careful note of certain reflex responses – a small movement of the wrist muscles, for example – and work out what those responses mean according to the context in which those responses occurred. In a way this is little different from what we already do with all our other senses: we use them too to interpret meaning from what we see and hear and sense around us. In dowsing we somehow combine together the information from all those ordinary senses, so that (with practice!) we have just one simple and consistent set of responses to interpret; and we’ll generally use some kind of mechanical amplifier, such as a small weight on a string, or a lever such as the traditional dowser’s forked twig, to make those responses easier to see and to recognise.

What may seem odd, at first sight, is that there don’t seem to be any physical limits to what we can do in dowsing. We can find some things, such as underground water, that we could not possibly see with our unaided senses; and with practice we can also search using information from images – such as a photograph or a map – rather than only from tangible, so-called ‘real’ objects around us. Although it might disturb scientists, who always have to have explanations as to why things work, it needn’t worry us at all: all we need to know, in practice, is how to make sure that we do find what we’re looking for. Dowsing rarely makes sense in theory, but does work surprisingly well in practice if you let it work. We can just get on with whatever we need to do, and let the scientists worry about it afterwards.

But since most people seem to want to know how things work, you will find a small section here on the theory of dowsing: though it’s almost at the end of the book. That’s because until you have some practical experience – which you’ll get by doing the exercises – it will probably be more of a hindrance than a help: so read (and work through) the rest of the book first!

While we don’t need to understand how dowsing works in order to use it, we do need to understand how to use it (which is not the same thing at all). And perhaps the most important thing to understand is that you’re not using an ‘it’ at all: you’re using you. As I mentioned earlier, what we’re really doing in dowsing is learning how to interpret our own natural responses to questions that we put to our environment. Tools such as the old divining rod or the ‘pendulum’, the weight on a string, do help: but they only help. As in all skills, what really matters in the end is you: your knowledge, your awareness. Far more than in most skills, dowsing only works well when you work well: so you can also use your varying results in dowsing as a way of telling you how well you know you.

For the same reason, there are no set techniques in dowsing. Everyone is slightly different: so everyone’s dowsing techniques will be slightly different. What works best for you now is what works best for you, now: not necessarily what worked well for someone else, and, unfortunately, not necessarily what worked well for you a while ago – even as recently as last week or even yesterday. Some dowsers would argue that, once learned, your dowsing skills and techniques need never change. But you change; things change; so your dowsing may well change too. (This is true for any other skill, of course, though it may not be so noticeable). Throughout this book I’ll be reminding you of that, to help you learn to notice when and how (and sometimes even why) things change.

To keep track of these changes, use a notebook as a permanent record. After each exercise, record what you’ve found out during the exercise. Do take the time to do this: you’ll find it invaluable in future. For the same reason, it’s a good idea to leave some space in the notebook after you write up your notes on an exercise, so as to leave room for further comments when you come back to the same exercise at some future time.

So, before you read any further, note down what we might call your ‘starting position’:

As I’ve said, you will find that it’s useful to have that kind of summary to refer back to later – if only to see how your views change as you gain increasing practical experience. There are no right or wrong answers here: just ones that work well, or not so well, for you, now.

1.1 Developing your skill

The idea behind this book is that it can be used as a workbook both to develop your dowsing skills from scratch, or – if you’ve already had some practical experience – to dip into to improve your skills and to try out new ideas.

There are five parts to the rest of this book:

1.1.1 A beginner’s introduction

If you haven’t done any dowsing at all before, Chapter 2, A practical introduction, will get you going, using some ‘angle rods’, basic dowsing tools that you can make from bits and pieces you’re likely to find around the house.

1.1.2 The dowser’s toolkit

The next three chapters look in some detail at what dowsers use as tools, and why they’re used in particular ways. Chapter 3, Make yourself comfortable, takes a more detailed look at angle rods, and also at the ways in which our approaches the skill can make a big difference in the reliability of our results; Chapter 4, The pendulum, will take you through the many variations on what is probably the most popular dowsing instrument; and Chapter 5, The dowser’s toolkit, discusses some of the bewildering variety of instruments that dowsers use as their ‘mechanical amplifiers’, and will show you the practical reasoning behind the choice of using one dowsing tool in preference to another.

1.1.3 Some applications

In the end, dowsing is only useful if you’re going to use it: this section will show you some of the many ways in which you can put your skill to practical use. Chapter 6, Putting it to use, gives practical suggestions on how to build up applications, looking at the basic principle of using dowsing to interpret questions that we present to our environment; Chapter 7, “Physician, Know Thyself”, presents some aspects of perhaps the most popular theme in dowsing, its uses in the areas of personal health and fitness; and Chapter 8, Finding out, instead, goes outdoors into the more traditional realm of dowsing, that of looking for things in the outside world.

1.1.4 Making sense

The next two chapters have a change of focus, looking inward but wider at the same time, to put dowsing into a more general context. Chapter 9, The greater toolkit, gives some practical suggestions to use dowsing – either on its own or in conjunction with other approaches – to look at how we interact with the world and with aspects of ourselves; while Chapter 10, So how does it work?, shows why attempts to explain the dowsing process create more questions than they answer, and that a more paradoxical approach to theory is perhaps the best way out.

1.1.5 Out in the real world

Finally, Chapter 11, A test of skill, shows you how to put your new skills and experience to some practical tests, including using map-dowsing and many other techniques to find real hidden objects.

2: A practical introduction

Dowsing is a practical skill, and as such only makes real sense in practice. So if you’ve never done any dowsing before, perhaps the first thing we need to do is get you started with some practical dowsing.

All dowsing work consists of identifying when the context of some small muscular twitch can be recognised as meaning something useful – such as the location of an underground pipe or a cable. As with riding a bicycle, we train ourselves to respond in a particular way to various bits of information that we select out from those that happen to be passing by.

On a bicycle, we pay particular attention to data received by our eyes and, especially, from the balance-detectors in the middle- ear, and we compare and merge those together to give instructions to muscles all over the body, to both balance and guide the bicycle. In dowsing we do something similar: but we seem to collect information from all of our senses, and direct it to just one set of muscles – usually the wrist muscles – to give the movement that indicates a response.

Because this movement is small and subtle, most dowsers use some kind of instrument, a mechanical amplifier such as a simple lever, to make the movement more obvious. Like the small side-wheels on your first bicycle, they make the learning stage easier; and, as with those side-wheels, they are something that we probably should, in the end, learn to outgrow.

But it’s true that it is much easier to use an instrument than to do without: something’s happening, you can see it and feel it much more easily. So much so that you’ll often feel that the dowsing rod is moving of its own accord, as if it has a life of its own. In fact, it hasn’t: it will always be your hand moving it. But that sense of it ‘being alive’ is usually a good indicator of when you’re allowing things to work, when you’re allowing all those internal senses to merge together within you to produce the end-results you need.

The other point that we need to recognise even at this stage is that there’s no one ‘right’ way to go about dowsing: there are no fixed rules, only the ways that work for you. But if anything goes, and anything can work, it’s difficult to know where to start. It’s much easier, at the beginning, to pretend that there is just one right way of doing it. Since we do need to start somewhere, we will begin with a set of perhaps rigid-sounding instructions: just note – as in fact you’ll find later in the book – that there are many variations, and if you feel uncomfortable with what I suggest here, do try something else until you find an approach that does feel right.

With that said, let’s get started.

2.1 Making a basic dowsing tool

The traditional dowsing tool is a V-shaped twig but, as you’ll discover later, it’s not exactly easy to use. So instead we’ll start with a pair of ‘angle rods’, sometimes known as ‘L-rods’ from their shape.

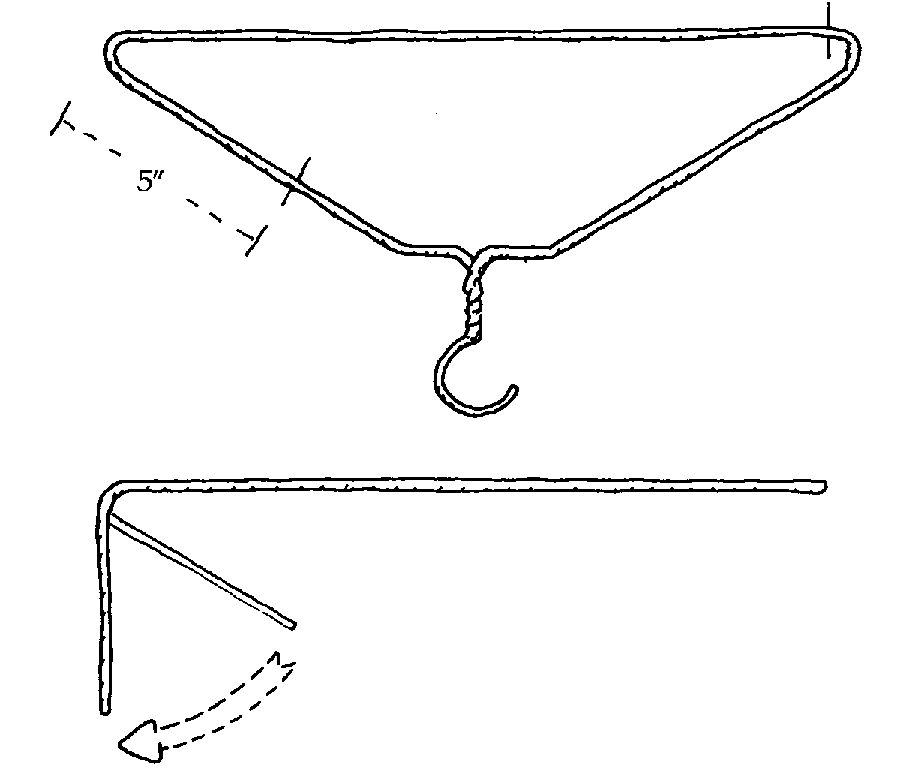

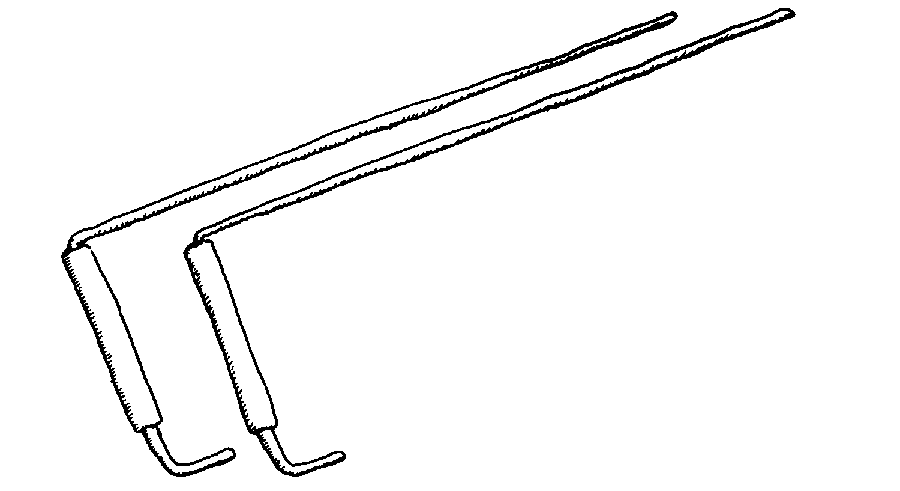

Figure 2.1: Making an L-rod from a coat-hanger

These can be made from anything that will bend into an ‘L’ and has a round enough cross-section to turn smoothly in your hand. Fencing wire, welding rod, electrical cable, plastic rod or even a pair of old knitting needles will do the job, but perhaps the easiest source-material to find is a wire coat-hanger.

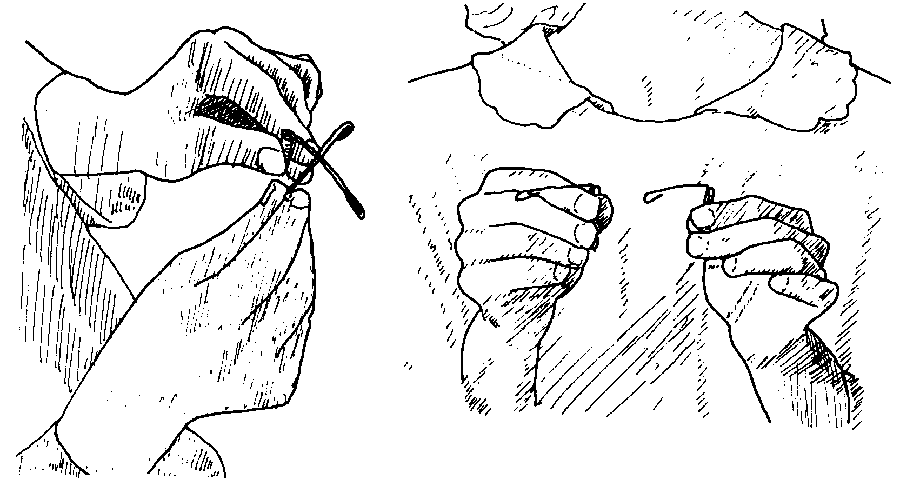

Having made them, you now need to know how to hold them:

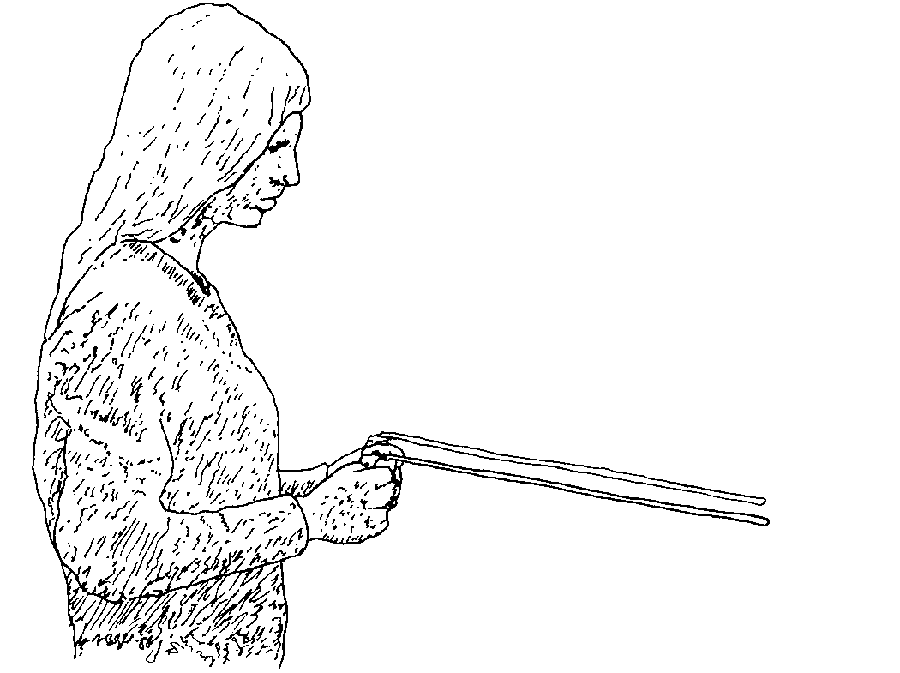

Figure 2.2: Holding L-rods

Held in this position, the rods are in a state of neutral balance, and will thus amplify and make obvious any small movement of your wrists, as the next exercise should show:

What we’re doing here is training the reflex response to come out in these wrist movements: a slight twisting of the wrist from side to side, which we can then see as a movement of the rods. The rods don’t move of their own accord: they’re actually amplifying the movement of your wrists. But in the next exercise, you should slowly find that it will seem that the rods are moving by themselves at your command:

Although this may sound a little strange, it’s actually no different from what we do when riding a bicycle. If you think too much about what your feet are doing or whether you’re balancing, you’re likely to fall off: instead, you concentrate on where you’re going, in other words treat the bicycle as an extension of you rather than as a separate ‘thing’ which you’re trying to control. That does take practice; that does take a certain amount of experience to change the all-too-conscious balancing efforts of your first few bicycle rides, to something where it’s so much a part of you that you don’t even notice the mechanics of what’s involved.

The same is true with these dowsing responses: it does take a little practice before it becomes automatic, before you completely stop thinking about what you’re doing, and instead concentrate on where you’re going, on what you want to do with the rods. So, before we move on:

One point you’ll notice is that when you let the rods ‘move by themselves’, they’ll move much more smoothly than if you move your hands deliberately. A technique that many dowsers use is to imagine that their rods are some kind of household pet that they’re watching and giving instructions and encouragement to, rather than something that they’re controlling; and you’ll probably find it easier to use a similar idea.

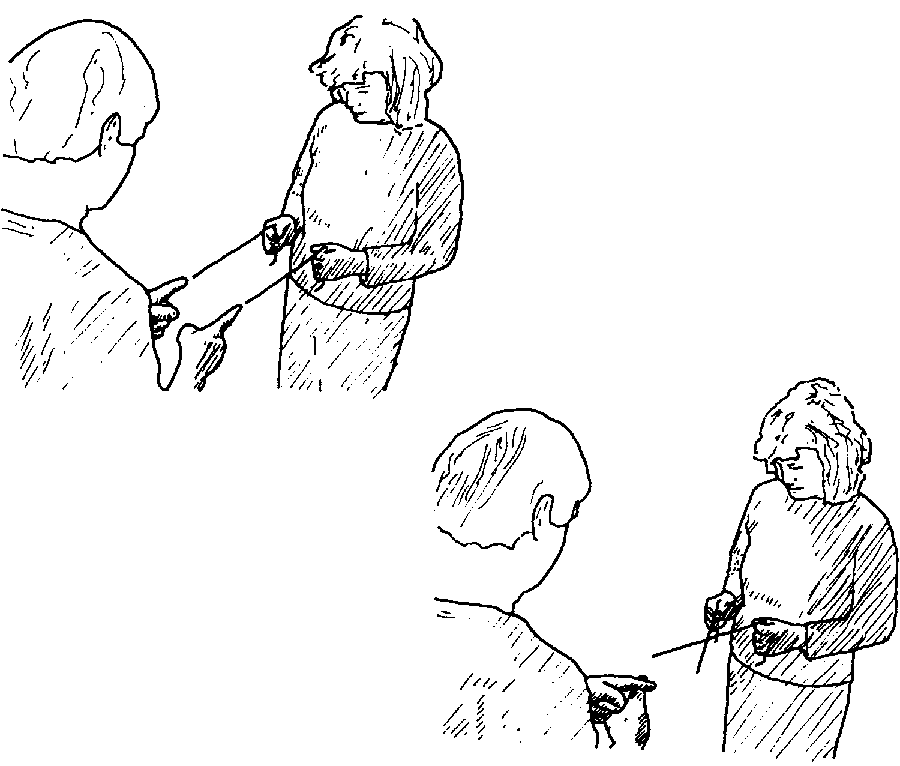

Figure 2.3: The ‘following fingers’ exercise

One way to illustrate this is to try the next exercise, for which you’ll need a partner:

This is, of course, a simple trick to redirect attention and stop the mind getting in the way. But it does work: it does make it easier to use the rods.

2.2 Extending your senses

In a way, though, we haven’t used the rods at all yet: all we’ve done is wrist-exercises, getting your reflexes used to the idea of what’s expected of them. In each of these exercises you’ve known exactly what’s going on, exactly where the requests for those movements were coming from – namely your own conscious awareness. What we now have to do is to find some responses to things that you don’t know. And that’s where the real magic starts:

What you’re likely to have had as results to that exercise is a mixture: a few movements you could attribute to plain physical causes such as tripping over the edge of the carpet; a few others where the rods seemed to move of their own accord, perhaps both to one side or the other, perhaps even crossing over; and, of course, a large amount of nothing much at all happening. That’s usual at this stage. But now remind yourself of that mental state you reached back in Exercise 5, where you could move the rods around simply by asking them politely to do so. If you didn’t ask them to move, they didn’t move; if you pushed them to move, it was obvious that you were faking it; but if you asked nicely and just let it happen by itself – ‘doing no-thing’, so to speak – things happened smoothly, cleanly, clearly. Now it’s not the action that happened there that we’re interested in, but the state of mind, of just letting things happen while at the same time setting up some limits or framework for things to happen in. With that in mind, let’s go back and do it again:

When you learn to ride a bicycle, there’s a knack to the balance which doesn’t come together and doesn’t come and doesn’t come until at some point – usually when you’ve just stopped trying – it all comes together and you have no real trouble from then on. The same is true of dowsing: there’s a real knack to the mental balance, the mental juggling-act we’ve called ‘doing no-thing’. Don’t worry if it’s all a little blurred at the moment: the knack, as with riding a bicycle, will come with time and practice.

2.3 Go find a pipe

At the beginning of this chapter I said that what we’re doing in dowsing is training ourselves to respond in a particular way to various bits of information that we select out from those that happen to be passing by. The key point there is that we select out from the mass of information those fragments that are relevant to what we’re looking for. If we didn’t do this, of course, the dowser’s rod would be about as useful as an open-band radio receiver: every channel being played simultaneously in a confusing cacophony of sensory images. It’s only when we select out, decide what we’re looking for, that we can merge those senses in a useful way into those reflex responses that we use in dowsing.

All our perceptual processes do this kind of separation for us, discriminating between what we choose as ‘signal’ and the rest of the background ‘noise’: it’s sometimes called the ‘cocktail-party effect’, from the way we can pick out a single conversation in the midst of the babble of a noisy party. To make sense of that kind of noise, we could use a variety of techniques: we might listen to the loudest talker, or point a directional microphone at someone. Or, more often, we can somehow just choose to listen, focus our attention on just one person, almost regardless of how loudly or quietly they’re talking, and let our senses merge together to do the rest. And it works.

One of the simplest ways of selecting something to look for in dowsing is exactly the same: just choose what you’re going to look for, and let your senses merge to do the rest. So, to complete this instant introduction to practical dowsing, let’s choose a simple example, namely looking for a water pipe in or around your house:

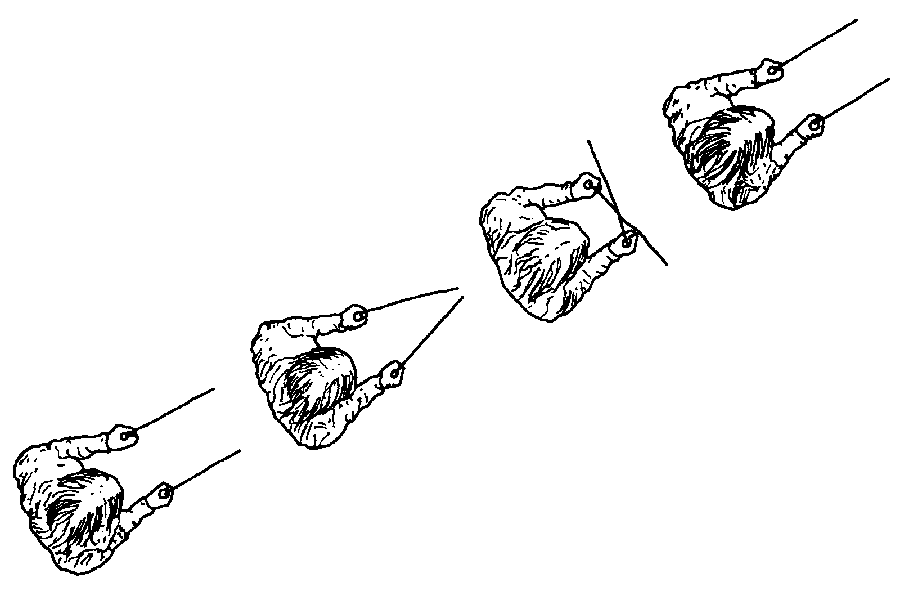

Figure 2.4: “X marks the spot” – a typical response

With the practice you’ve had by now, your response as you crossed the pipe should have been something like that shown in Figure 2.4: the rods cross as you walk over the pipe, and then open out parallel again. Don’t be surprised, though, if you overshoot the pipe a little, so that you get a slightly different location according to which direction you cross the pipe. (This is because your reflex responses aren’t fast enough yet: your body’s still a little uncertain of what to do when, rather like that wobbling stage of learning to ride a bicycle.) And don’t be too concerned if it didn’t work out that way: it doesn’t mean that you can’t dowse, it just means that you need more practice, of which you’ll find plenty as we go through the rest of this Workbook.

So let’s move on to look at that practice in rather more detail.

3: Make yourself comfortable

There’s no way you can work well in a new skill if you aren’t comfortable with it, and dowsing is no exception. And there are two sides to that ‘comfortable’ feeling: not just being comfortable with the tools you use, but also comfortable in yourself, being confident in what you’re doing.

To my mind, most of what we need to learn in dowsing falls into the latter category: it’s mainly about interpretation, about what we perceive from the information we receive. That’s why dowsing is such an interesting skill, because so much of it depends on you, on who you are – so much so that you can use it as a mirror of how well you understand yourself.

But there is a physical aspect to this, and that’s to do with the tools we use to amplify the wrist muscles’ dowsing response. Quite small physical changes can make a big difference in how well, and how quickly, angle rods respond to a given wrist movement. So by making pairs of rods in different ways and out of different weights and sizes and types of material, we can explore a variety of subtle if solely mechanical effects on what feels comfortable, on what feels ‘right’ in a dowsing instrument.

3.1 Variations on a theme

Your angle rods are levers using neutral balance as the mechanical principle to amplify your wrist movements. Everything depends on that balance, and the freedom to move that’s implied by a neutral balance, neither stable nor unstable.

We looked at some of this in Exercise 4, where we saw the effect that your wrist angle had on how much the rods moved and how easy – or not – it was to keep them stable. The joint-angle of the angle rod itself – between the short and long arms – has a similar effect. To begin with, as in the last chapter, a merely approximate right-angle is quite good enough, but it is worthwhile experimenting with it to find the angle that’s most comfortable for you:

Another very simple change to try is to turn the rods upside-down:

Some people also like to use handles, so that the rods can turn more easily; others prefer to feel the movement of the shaft of the rod directly against the skin of their fingers. Find out which approach works best for you:

You’ll probably have found that using handles does make a lot of difference: it makes the rods far more mobile but also, in a way, less tangible, less certain; and the wrist-angle and, especially, the joint-angle, become far more critical in their effects on the rods’ rate of response. In general, if I’m using a rod made of some relatively lightweight material such as a coat-hanger, I prefer to do without handles; but if I’m using some heavier material such as the 3/16” mild steel rod used in my favourite commercially-made pair (see Fig. 3.1), the handles are almost essential, and do give me a sense of certainty about the response. But that’s my choice: what works well for you is what works well for you, not necessarily what works well for me!

Figure 3.1: Commercial rods with handles

The actual material we use for angle rods can make a lot of difference to how well they work for you, partly for good physical reasons, and partly from a more indefinable sense of what does and does not feel right. So it’s worthwhile experimenting by making sets of rods from different materials and in different ways – variations on a theme of angle rods – to see what effects they have in what works well and what doesn’t work so well.

For this group of experiments you’ll need a better supply of rod-material than coat-hangers, or you won’t have anything left to hang your clothes on! Two alternatives that should work well and don’t cost much are welding or brazing rod, or stiff single- core electrical wire such as earthing cable – both of which you should find at your local builders’ supplies store.

You’ll certainly have noticed a difference there: the response will have been much more twitchy and unstable than with the arms the other, more usual way round. (If it didn’t move at all, you were holding the shaft too tightly, so that the smaller inertia couldn’t break the starting friction of your grip. If that’s the case, relax a little!) In some circumstances, though, it’s useful to have it be less stable – you get a faster response – and the shorter length of rod is less likely to get tangled up with the wall as you walk around…

Let’s continue that theme a little further, and try out the effects of a whole sequence of different lengths:

Changing the length of the rod changes both the centre of mass of the rod – and thus its response time – and the overall weight. One side-effect of changing the overall weight is that the inertia also changes: if you reduce it too far, the rod becomes more and more susceptible to being pushed around by the wind and similar interferences. One way of moving the centre of mass without changing the overall inertia is to mount a small weight, such as a lump of modelling clay, onto the rod, and move that to various positions on the rod. The further away from the axis (your fist, in other words) that you move the weight, the further out goes the centre of mass, and the more-smooth but slower- reacting becomes the rods’ response. Try it:

The effect is most noticeable when the weight is towards the end of the rod: it tends to emphasise very strongly the swing of the rod. If you like the feel of a weight on the rod, you could also try some other materials such as lead fishing weights. Some dowsers, especially those doing outdoor work, greatly prefer these moveable weights; I don’t, as it happens, partly because with them the rods swing around more than I like and partly because they tend to pull my hands down and generally make a long outdoor session that much more tiring for me. But as usual, it’s your choice: see what works best for you.

So far we’ve made all our angle rods out of one kind of metal or another. But there’s nothing special about that: we need a material for the rod that’s long, thin and as close to circular in cross-section as will turn easily in our hands, and the most common sources of materials that fit that description are metal, such as the ubiquitous wire coat-hanger. We could just as easily make it of some other material, as long as it fulfils our mechanical requirements: in fact some dowsers have what you might call a magical objection to using metals at all, saying it frightens the energies away (whatever those might be). Try it out: see if you agree with them. In any case, it’s worthwhile getting into the habit of being inventive, of always being willing to try something new:

Don’t panic if you couldn’t think of anything else to use: it really doesn’t matter, this is a workbook, not a competition. The point of that exercise was to re-emphasise a theme we’ll be returning to throughout this book, namely inventiveness to find what works best for you.

Inventiveness has to stop somewhere, and even I was surprised when someone turned up at one of my groups with a beautiful pair of miniature angle rods, to be held between finger and thumb: we’d played with changing the length of the rods, of course, but I hadn’t thought of changing the scale of the rods that drastically (see Fig. 3.2).

Figure 3.2: Miniature angle rods

He’d designed them for use in map-dowsing, which is something we’ll look at later, but they’re an interesting variant of angle rods to play with anyway:

Even with rods this small, you’ll soon get used to watching the rods out of the corner of your eye, so that you can concern yourself more with where you’re going, where you’re standing – much as with riding a bicycle. And as with the bicycle, it’s at that stage that everything suddenly becomes much easier: you don’t have to think about balancing, you just do it.

In no time at all you’ll find that you can just pick up almost anything that you could use as a pair of angle rods, adjust it to whatever balance feels comfortable for you, and get going. All it takes is practice!

3.2 Mind games

The other half of being comfortable in dowsing is being confident in yourself and in what you’re doing. So: what are we doing?

In some ways, to be honest, we don’t know. We do know that we’re aiming to use those reflex muscle responses to point out when we’ve found something: but we don’t really have a clue how we do it. We just, well, do it. Somehow.

This is where most people wander off into theory, and where I will simply sidestep the whole issue by saying that it’s entirely coincidence and mostly imaginary.

What? Entirely coincidence and mostly imaginary?

To make sense of that, we’d better take a brief diversion at this point into some mind games, and then forget the whole subject until Chapter 10.

What we’re doing is, literally, looking for a coincidence: a co-incidence – with the hyphen emphasised – of where we are and what we’re looking for. (You could also say event – it sounds more scientific than ‘co-incidence’, if not quite so precise). Just like all our other senses, we’re using this ‘dowsing sense’, this merging of other senses, to pick out a change in the surroundings that’s meaningful to us, using clues that we choose as being meaningful – such as the muscular twitch that we’ve trained ourselves to recognise as the dowsing response.

The way that we assign meaning and select ‘meaningfulness’ is through what we see as the context of the event, which we describe through ideas and images – in other words, in what is, literally, an image-inary way. We learn to recognise (or, more accurately, choose) that certain things are meaningful, while others aren’t: this movement of the rods was significant, while that movement was simply my being careless and tripping over the edge of the carpet. We interpret the coincidences according to what we see as the context of those coincidences.

This is true for all of our forms of perception: dowsing is no different. I hold in my mind an image of what I’m looking for - “I’m looking for a water-pipe” – and until I’ve found it, it is, of course, entirely imaginary. What we’re learning to do in dowsing is to find a way to bring an imaginary world – what we’ve decided we’re looking for – and the tangible object in the physical world – the water-pipe, in this case – together, through the overall awareness of our senses. Or, to put it in a simpler way, we’re trying to find a way to get us to know that we’ve coincided with the water-pipe when we didn’t know where it was in the first place.

So we need to know when that event, that coincidence has happened. And to do that we need to have a clear understanding of three simple questions with sometimes not-so-simple answers:

- Where am I looking?

- What am I looking for?

- How am I looking?

All dowsing techniques address these questions in various ways, but let’s look at them in more detail as they relate to the use of our angle rods.

3.2.1 Where am I looking?

In order to make sense of a co-incidence – the rods’ response – we have to know precisely where it’s occurred. At first sight the answer to “Where am I looking?” seems obvious: I’m looking here. But stop and think for a moment: just where is ‘here’?

We know that ‘here’ is somewhere down by your feet: but in practice we usually need to be more precise than that. We need to know exactly where that pipe is; we need to know the exact place on the ground meant by that co-incidence of the crossing of your angle rods. Since that point isn’t obvious, we choose one.

This perhaps sounds a little strange, but it really is no different from the way we choose to listen to one person rather than another at some noisy party. Our perceptual systems can – and do – select out the timing of information, giving us warnings about relevant co-incidences: here we’re just making use of that inherent ability of ours in a slightly different way. We choose where ‘here’ is.

The hard part, then, is making sure that the rods know, so to speak, of where your choice of ‘here’ happens to be. So just tell them: it’s as simple as that. As with riding a bicycle, your senses will do the rest, once they know what you want. But if you can’t make up your mind, there’s no way that your dowsing can be accurate. So choose.

With angle rods, the best choice is often ‘the leading edge of the leading foot’:

By choosing to mark ‘here’ in different ways, you can resolve some practical problems that might otherwise be awkward. For example, it’s difficult to track a pipe close to a wall, because the rods tend to get tangled up with the wall as you walk closer to it. So one solution is to change the way you mark ‘here’, simply by walking backwards:

You can mark ‘here’ in any way you like, as long as you can make clear to yourself where ‘here’ is. If you’re using a pendulum for dowsing (as in the next chapter) rather than angle rods, you can use a hand or a finger to point out ‘here’, or point in a particular direction, with the line of ‘here’ stretching outward from you to infinity. Or you can be more imaginative, and say that ‘here’ is the place represented by some point on a photograph or a map – hence map-dowsing, of which more later.

It’s up to you. It’s all up to you. That’s the great strength of dowsing; but it’s also the reason why it can sometimes take a great deal of practice and discipline to get it to work well.

3.2.2 What am I looking for?

The rods’ reaction at some place shows that we’ve found a co- incidence with something there: but it’s difficult to know what they mean unless we know that we’re looking for something. We have to tune the radio, so to speak; we have to be selective, we have to choose.

So almost before we do anything else, we have to decide what we’re looking for: otherwise (to use our anthropomorphic analogy) the rods won’t know what to respond to, to mark the co-incidence that we’d like. One the real disciplines in dowsing is in learning how to be clear, precise and specific about what it is that you’re looking for.

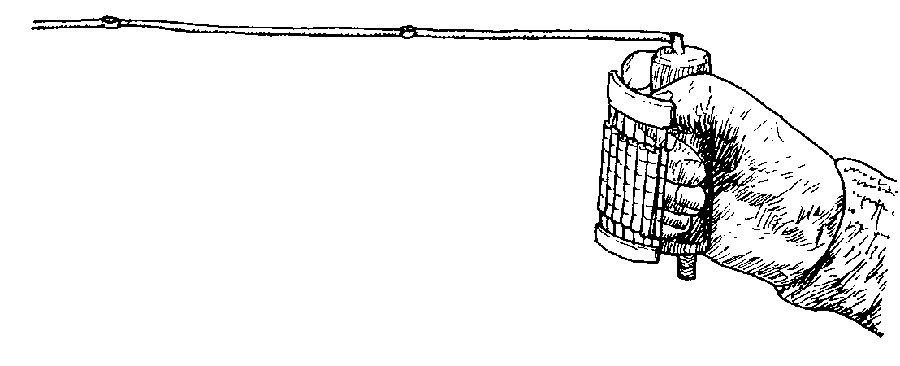

One way to do this is simply to hold it in your mind: in other words, say to yourself “I’m looking for…” (whatever it is – a water-pipe, in our previous examples). Frame it in your mind: imagine it, image it:

Another common method is to carry a sample of pipe-material with you, to use as a tangible reminder of what it is that you’re looking for. One commercially-made dowsing kit, designed for use by surveyors, actually came complete with a set of samples of piping materials wrapped around one of the rod-handles – see Fig. 3.3. (For historical reasons, American dowsers tend to refer to this kind of sample as a ‘witness’). Or you could write it down on a piece of paper as a kind of verbal sample – “I’m looking for a water-pipe that’s like this” – or perhaps draw it: anything, as long as it’s a useful prompt to make it clear to your rods (in other words you) what you want their response to coincide with.

Figure 3.3: ‘Revealer’ rods with set of samples

You can, of course, find things other than water-pipes with your angle rods. In principle, you could find anything, since all you’re doing is using the rods to indicate the co-incidence between where you are and what you’re looking for. In practice, of course, we tend to look for more tangible objects: cables, keys, cashew nuts or whatever. All we do is change the rules: tell the rods that we’re looking for this, rather than for the pipe as before. Try it:

Whenever you’re using the rods, there’s always a little ‘noise’ mixed up with the signal: the rods drifting this way and that at times, for no apparent reason. At this stage you’ll probably be just beginning to recognise when there’s a real ‘signal’ response from the rods: there’s a quite different feel to it, a sense of ‘this one’. But while most of the other twitches and wanderings may well be meaningless, don’t be too quick to dismiss them all as ‘noise’: sometimes they’re trying to tell you something.

The same is true at that noisy party, of course: sometimes you’ll hear interesting snatches of conversation that drift out of the background babble – or important messages such as “Food’s ready!”. The dowsing equivalent would be the rods giving you further information about what you’re looking at, such as a joint or branch in the pipe, or the direction the pipe’s going in; or else telling you that you’re walking over something that’s not specifically what you’re looking for, but may be relevant and that you ought to know about, such as an electrical cable that needs repair.

One of the important tricks in dowsing is to leave some kind of space in the rules that you’re using, so as to allow these ‘not- in-the-mainstream’ messages to come through – rather as you’d keep half an ear open, so to speak, for other information at the party. As at the party, the best indicator is always that clear ‘feel’ when something is meaningful – it ‘stands out from the crowd’, we would say; but one way to help it is to build other types of responses, in addition to ‘X marks the spot’, into the rules that you set up for your rods to follow.

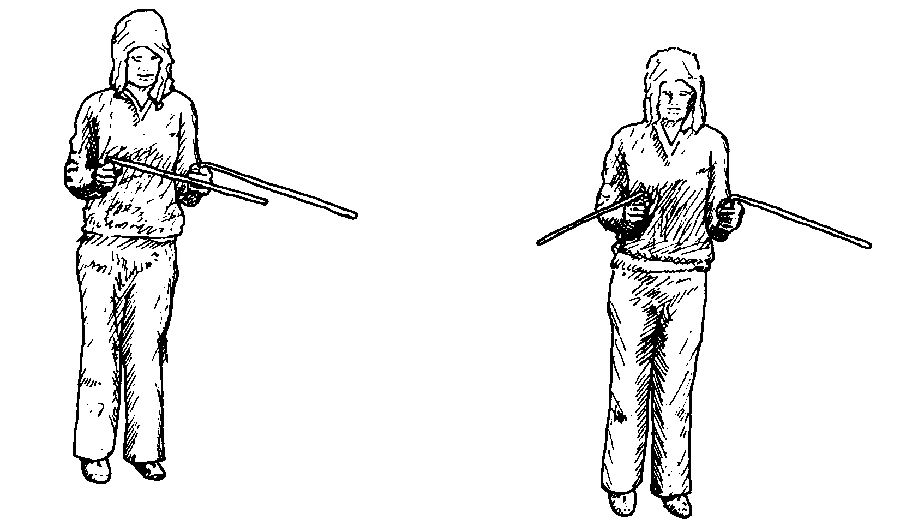

Figure 3.4: Some more responses: direction and ‘something else’

A good example of one of these extra rules, or extra response types, is what we might call ‘they went thataway’, for which the rods both move parallel to point out a different direction (see Fig. 3.4). You could also set up that the rods move in a similar way to point out a shape or an edge – particularly useful if you’re trying to find buried walls at an archaeological site, for example. And another move is what I call the ‘anti-cross’, in which both rods swing outward instead of inward – I set this up in my list of rules to tell me that there’s something else important here, even if I’ve not specifically been looking for it (somewhat the equivalent of hearing “Food’s ready!” during your conversation at the party).

Practice with this for a while, switching between the two sets of rules: ‘I’m looking for the pipe (or whatever)’ and ‘I’m looking for the direction of the pipe’.

Having found the direction, it would now be useful to track along the pipe instead of marking it with a series of passes of ‘X marks the spot’. We can do this by asking the rods to continue to point out the direction that we should move in so that we can walk directly along the course of the pipe:

Don’t be too concerned if what you’ve mapped out is best described as a drunkard’s walk, rather than what was supposed to be the straight line of the pipe. How well could you travel in a straight line when you first learnt to ride a bicycle? Not exactly a straight path then, was it? The same is true here: until you’ve had a lot more practice, you will often tend to ‘hunt’, or overshoot the line, over-correcting each time you cross the pipe – hence the wandering line that you’ve marked out. The overall course probably will be correct, even now, when you come to check it out. Once again, all you need is practice!

And along with that you’ll also need practice at that balance of looking for something specific, some specific co-incidence, whilst at the same time keeping yourself open and aware for other possibilities, other information:

What we’re doing in dowsing, in effect, is building layer upon layer of rules for the rods to follow, to tell it exactly what co-incidence to respond to. Layer upon layer of rules within rules, sub-clauses, ifs, buts and perhapses, all building up as precise a description as we can of what exactly it is that we’re looking for and in what context (or contexts) we’re looking for it. In a way, we’re programming the response of the rods, rather like programming a computer.

But the computer here is not some external machine, but our own overall awareness, sensing for some specific co-incidence. The computer program has its input and output; the input here is that merging of all our senses into what seems at times to be a separate sense, and the output is directed into one place, the reflex muscle responses that we see and feel in the movement of the angle rods. The catch, as in computing, is ‘garbage in, garbage out’: if you don’t take enough care over the instructions you set up for that ‘bio-computer’, the results will, all too often, turn out to be nonsense, rubbish, garbage. So it’s important to consider not just what you’re doing, but also how you’re doing it, what your mental ‘set’ or state of mind is while you’re working.

Which brings us back to the third of those three questions that we need to ask, namely:

3.2.3 How am I looking?

The way in which you approach any skill is important; but in dowsing it’s absolutely critical. Approach your work with the wrong kind of mind-set, and you’ll usually find yourself getting nowhere slowly. Your mind-set matters. A lot.

As with riding a bicycle, there’s a delicate balance to be learnt: a balance of mind rather than body. Assume you can’t do it and, yes, you’re right, you can’t do it. Alternatively, assume that you know exactly how to do it, you know everything there is to know about it, and, strangely enough, you’ll probably find that you can’t do it. What actually does work is even stranger: try extremely hard for a while, and then quite deliberately give up. Just let it happen, without trying, and it works, as if by itself, with you doing ‘no-thing’ to make it do so.

Do nothing, and nothing happens; do something, trying to make it happen, and and once again nothing happens; instead, you have to reach that delicate balance of ‘doing no-thing’.

It’s perhaps easiest to understand that balance by exaggerating what not to do:

Here we’ve been exaggerating, of course, but those nibbling little doubts and under-confidence with which most people start are likely to have much the same effect. The trouble is that those inner doubts are subtle, so their effects are subtle too. Learn to watch your own responses closely, and you’ll see how your dowsing can become a useful mirror of your current state of mind.

The same is true of over-confidence, in that it can wreck your results just as effectively as doubt:

Well, it may have given your confidence – and your results – a boost for a while, but the most common ending of that is the phrase ‘Pride comes before a fall’. A big one. A long, long drop. If you ever reach a point where you’re certain you know it all, that’s when you’re likely to be just that little bit over- confident – with disastrous results. Every skill is a learning experience, for a lifetime: you never do get it perfect. And if you spend much energy on protecting your ego from the inevitable bruises, you’ll never get much done. So again, your dowsing can become a useful mirror of that aspect of your current state of mind: by watching your results, you can watch you at the same time.

Over-confidence and under-confidence are variations on a much more wide-ranging theme of assumptions. We assume things to be such-and-such a way; since these then form part of our mind-set while we’re working, they’re included in that list of rules that we set up for the rods to respond to in marking the coincidence we’ve said is going to be meaningful. So the rods, obliging as ever, will respond exactly according to that list of instructions – leaving you to disentangle the confusion of whether they responded to a real object like a pipe, or an imaginary ‘object’ like “I can’t do this”. If your instructions to the rods – your instructions to you, that combining of your senses – are riddled with assumptions, it’s not going to be too likely that your results will be of much use.

This applies not only to attitudes like over-confidence, but also to assumptions about repeatability and the like. Let’s take a typical example:

It’s up to you. Your choice. You can spend all of your time looking for imaginary objects – which your rods will quite happily find for you in some imaginary world, but not, unfortunately, in this so-called ‘objective’ world that we happen to share with everyone else. Or you can pay attention to what assumptions you’re placing on the way that you work: in which case you might well get some useful results. (With practice, of course!)

There are occasions, though, where you can put the blocking effect of assumptions to practical use, by deliberately ignoring some information that would otherwise get in the way – rather like shutting out the gabbling of some load-mouthed oaf at the party so that you can listen to the quiet-voiced woman next to you. In other words, we declare that something is ‘noise’, even if it was useful information a few moments ago. Just ignore it, tell yourself that it isn’t there any more – rather as you would wish was the case with the loud-mouthed oaf!

One example would be when trying to find something with water in it, other than the water-pipe:

Properly used, this kind of ‘selective ignore-ance’ can be an immensely powerful tool. We have in fact used it already, back in Exercise 25, to get the rods to show us direction rather than position; and again in Exercise 26, where we followed the course of that one pipe and ignored any others that we might have crossed.

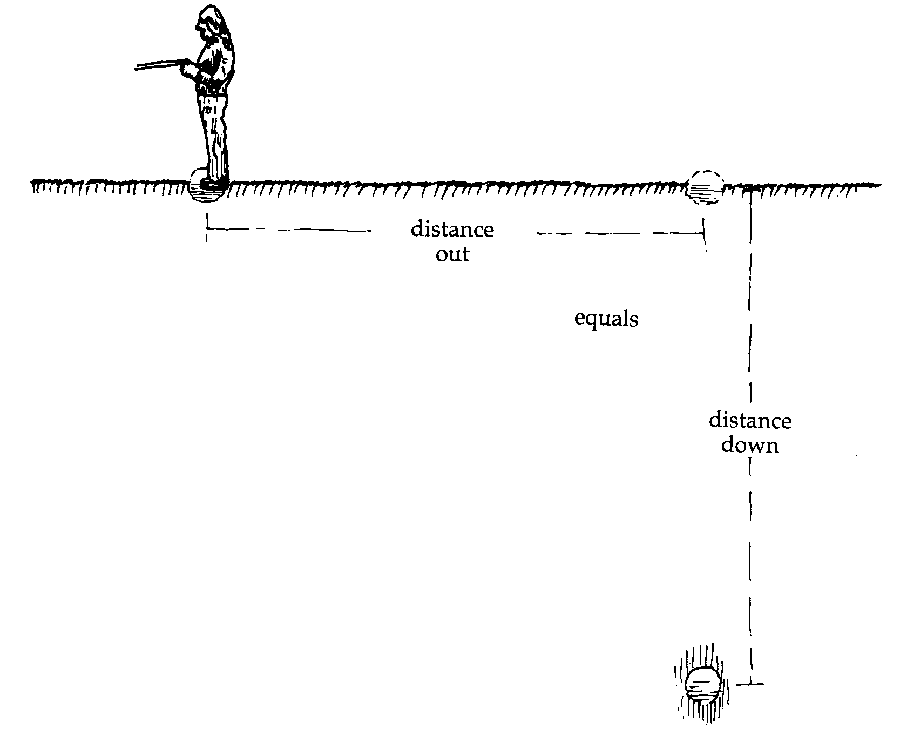

Figure 3.5: Finding depth with the ‘Bishop’s Rule’

We can use a similar process to find the depth of the pipe, with a technique known as the ‘Bishop’s Rule’ in dowsing circles for at least a couple of centuries (see Fig. 3.5). We mark a point directly above the pipe; then when we get another response from the rod, the distance back to where we started will be the same as the depth of the pipe at our starting point – in other words, ‘distance out equals distance down’.

In all of this, do be inventive, and do remember to check things out for yourself. For example, some dowsers find that the Bishop’s Rule works in a rather different way: ‘distance out’ may be half or twice distance down, or some other factor. And that won’t be very helpful if you’ve presumed that someone else’s assumptions about experience (which is all a ‘rule’ is in reality) must apply to you: you may find yourself digging a great deal further than you thought to find that pipe!

And remember to maintain that delicate mental balancing act of ‘doing no-thing’: asking politely for things to happen, and letting things happen the way they want to in return. It is a subtle balance, and it does take practice: but if you’ve been doing the exercises rather than just reading them, you’ll be well on the way to reaching that balance by now.

10: So how does it work?

I did promise that we’d look at how dowsing works, how it all happens. But perhaps the best way to start this section is for you to ask yourself the same question:

(A clue: if you’re certain you know how it all works, you’re probably not looking close enough…)

I’ll be honest: I don’t know how it works either. At least I know that I don’t know, which is something. Every time I try to pin it down to a particular theory, a particular approach, it always manages to wriggle around and present me with something that works in a way that I didn’t expect. As long as I’ve let it work, of course.

Dowsing has always done this. Look at some research reports – Tromp in the ’30s, Maby and Franklin in the ’40s, Taylor in the ’70s – and you’ll see the same pattern every time. Whenever someone’s tried to do a scientific study, whatever makes dowsing work has either sulked and refused to play at all in the laboratory (though continued to work quite happily outside), or followed the experimenter’s theory for a while and then suddenly changed its mind, and worked some other way instead. Awkward as ever!

But in a way there’s no point. As we’ve seen, we don’t really need to know how it all works, as long as it does actually work. Dowsing is far more a technology than a science: and all we need to know in any technology is how it can be worked. Any theories we might have are – or should be – just sources of ideas for better ways to work it in practice.

It might be much more comfortable to have an explanation that looks something like what other people would accept as ‘fact’: but we don’t have one. None that would stand up to any real scrutiny, anyway. Still, the one fact that we do have is that it does work, for most people – with a little practice and a few interesting acts of mental acrobatics, perhaps, but it does work. (Assuming that you have bothered to do at least some of the exercises by now, you’ll have proved that to yourself, in practice.) So even without an explanation, it still works!

And that’s why I’ve been careful, throughout this book, to explain the whole process by not explaining it at all, with that simple ‘non-explanation’ that it’s all co-incidence and mostly image-inary. We’re putting coincidence to practical use. Without some consistent theory that truly could encompass every aspect of dowsing, that really is all we can say about it.

But if that’s so, what is coincidence?

10.1 It’s all co-incidence

The question is more important than it looks. At first, the answer seems to be obvious: it’s just coincidence, isn’t it? There doesn’t seem to be any point to the question. But stop for a moment, and try to describe it in relation to anything else: and you’ll find you can’t. Coincidence is, well, coincidence. You know: coincidence.

All we can do is describe it as itself. We can use an alternate name – ‘event’, for example – but since that is exactly the same, that tells us nothing. And yet it’s very real: we certainly experience it. So what is it?

In one sense coincidences don’t have meaning: they’re just events. But in another sense they most certainly do have meaning: a peculiar thread that cuts across all our ideas about what is and isn’t ‘normal’ in our lives. For most of what we experience, we have a good idea of what supposedly caused what: but we also all have many examples of events and connections – very real connections – that make no sense at all in terms of cause and effect. There is a kind of sense there, but just what is not at all easy to grasp:

One thing that makes these events seem so strange is that they’re out of our control. Cause-and-effect we understand; these games of the Joker, these instances of ‘wyrd’, we don’t. They’re even a little frightening at times – perhaps because our sense of security, in this culture, comes from our relative certainty of being able to predict what’s going to happen.

But given the infinite nature of reality and our finite grasp of events, the best we can do with causality is predict what’s likely to happen, and even then only in the crudest physical terms. Since we’ve all be told endlessly since childhood that things happen because this causes that causes the next (and so on), it’s a bit of a surprise when we finally realise just how limited in usefulness – as a predictive tool – the concept of causality can be:

Look at it like that, and it’s obvious that there’s something else. Just what that ‘something else’ actually happens to be, is not really something we can grasp: as with time – another ‘something’ that is real yet quite intangible – it just is, and that’s about all we can say.

Whenever we think of cause and effect, we’re thinking in terms of time. Whatever event we describe as the ‘cause’ always occurs before its supposed ‘effect’. In other words cause-effect chains are patterns in time. And precisely because they are patterns that we can recognise, we can use them in a predictive way (though often we can perceive them as recognisable patterns only after they’ve occurred, which may be a little late…). We don’t actually know why they are patterns, without describing reasons ‘why’ in terms of others of those same patterns – a classic example of circular reasoning which gets us nowhere. So that’s all they are: patterns.

And they’re not the only ones: there are also these other patterns, such as the ones we’ve been studying and learning to recognise in this book, that seem to occur ‘acausally’, quite outside of time. Some of them, as clusterings of apparently random events, Kammerer termed ‘serialities’; others, groups of entities (concepts, physical events, dream images and the like) occurring at the same moment and linked by a subjective sense of meaning, were termed ‘synchronicities’ by Carl Jung. But there are many other classes of these acausal connections: and at least one of them, it seems to me, is what is behind dowsing. An understanding of causality may be the key to the conventional technologies: but an understanding of acausality, these connections without connections, leads us to the equally real technology of dowsing, and much more besides.

So we never will be able to describe what causes dowsing to work, because whatever makes it do so, whatever it is that’s behind it, exists largely outside of any concept of cause and effect. It seems increasingly likely that the only truthful answer to the question “What makes dowsing work?” is “Yes”. Or “Idiot”, perhaps – ‘un-ask the question’.

The Norse legends described life as a web, a roll of cloth being woven by the three Fates, the ‘three sisters of wyrd’. So, by analogy, causality is the weft of that web, threaded across time; and acausality is the cross-warp, weaving its multicoloured way through the normality of our lives. And coincidences? They’re the knots in the mesh, the points where the threads co-incide and cross. Coincidences are points that exist not just in time and space, but also quite outside them, totally beyond those limitations, in fact cutting across anything we could understand as time or space.

So everything really is all coincidence: it’s up to us whether we put those coincidences, those opportunities, to use. Dowsing is entirely co-incidence, mostly image-inary: using our imagination to put coincidences to use. In choosing to do so we also choose to move across that warp, moving momentarily outside time and space – and, perhaps, change our fates in the process!

10.2 A question of time

I did also promise, earlier in the book, that we’d take a look at time, and especially why dowsing in time is so fraught with difficulties.

If you’ve managed to make sense of the discussion above, you’ll see that the reason is quite simple – even if the implications are anything but simple! Our experience of events is of coincidences in a web of causality and acausality, in which time is in some ways a dimension. We see cause-and-effect as recognisable patterns of events in a sequence in time. And we can also see other patterns, and learn to recognise other acausal patterns that run across the apparent linearity of time – and those, it seems, are what we’re working with when we’re dowsing in time.

What confuses everything is that while we experience time, it’s quite imaginary. The past is gone, the future never here: all we can ever know for certain is now – a ‘now’ that we can never grasp, because as soon as we observe it, it’s ceased to be the same ‘now’. So time doesn’t exist – at least, not in the sense that would apply to those three tangible dimensions of height, width and depth.

All physical events, the effects of causes, are patterns in time – and since we see them as patterns in time, it makes it very difficult to look at time itself. The physical definition of our standard unit of time, the second, is described in terms of the duration of a specific frequency of radio waves: another example of circular reasoning, since frequency is itself defined in terms of time. And time is assumed to be linear and regular: an assumption which we have no way to check at all, since any method for doing so would exist within that same time, linear or non- linear, regular or irregular.

Physical time is assumed to be linear (relativity theory not with standing). But those cross-currents of coincidence are more like loops, threading back and forth through our lives. In dowsing, we’re linking across acausal loops in time and space in a way that we can still barely comprehend.

Our experience of time is anything but linear: ten minutes of rushing to catch a train is a far shorter period of time than ten minutes waiting for it at the other end. And for tribal people, time is measured by the day, or the season, and the shortest recognised time-unit may well be the time a pot takes to boil – which, as we all know, is far longer if you watch it than if you don’t.

Time is imaginary. And coincidences are events both within time, and outside of it – some of them points where the Joker’s warped mind cuts across the threads of normality, giving us those chaotically confusing but useful coincidences I call ‘Normal Rules’. It’s all entirely coincidence, mostly imaginary.

The past is imaginary: a photograph, as a record of a moment in time, is literally ‘image-inary’. And the future is imaginary: we can only imagine it, because it doesn’t yet exist in any tangible sense. We push towards our choice of future with intention, or will. But since everybody else is doing the same, there’s no way we can predict the outcome with any certainty. We can see when something is likely to happen: but there’s no way that we can ever be certain that that particular image-inary world will ever coincide exactly with the physical world at the precise moment we’d need for certainty. There are just too many forces acting upon it, too many threads of time pulling the future this way and that.

Whichever way we look at it, time is a maze of paradoxes.

So, given the paradoxical nature of time, the best we can ever hope to achieve, in dowsing with a different ‘now’, is a past or future with a high probability of being valid. The conventional tool of statistics won’t help us much, either: statistics are only useful with large numbers of events, whereas here we’re looking at just one. All you’re left with, in the end, is your skill at interpreting possibilities. And that, in effect, is what you’ve been learning and practising in this book.

So what does it all mean? What is time? In a way, it’s probably best to use another ‘non-explanation’, and say that it just is: whatever it means, we’ll find out later, looking back in time, with all the advantages of hindsight.

With both time and coincidence, we seem to end up going round in circles if we try to make sense of them in a way that we can describe in ‘objective’ terms to others. They just are: that’s all. But we can put them both to practical use, as long as we can accept that we’ll probably only understand them in our own experience and practice.

If you look at it in that way, getting those coincidences of your dowsing to work well for you is also a question of time: a matter of taking the time to put it into practice. Doing it: not talking about it, or thinking about it, or arguing about it, but doing it.

Since practice is really what matters, that’s probably the best way to end this book. And that’s why the next (and final) chapter contains nothing but practice!