Chapter 9 - Polymer - Building with Web Components Today

In chapter 8 we took a look at the W3C standards proposals that comprise “web components”. We also provided example code snippets that can be executed in Chrome Canary, the beta version of Chrome that has many experimental features not yet in production browsers.

While Chrome Canary can be fun for experimenting with new web technology, due to security and stability issues, that’s all it can be used for. For those interested in moving beyond Canary experimentation, Google’s Polymer team has created a number of polyfills (platform.js) that can simulate “most” of the web components standards in today’s production browsers. In addition to providing polyfills for <template>, custom elements, shadow dom, and object observables, the Polymer team has created a custom element based framework (polymer.js) that ties together these technologies with some syntactic sugar. The Polymer team has also created a set of “core elements” and UI elements (now called paper elements) that provide several SPA application features such as AJAX and local storage wrappers plus much of the UI page structure that is found in most web apps such as menu, dropdown, and header elements (sound familiar?).

http://www.polymer-project.org/

The Polymer team has even created a “designer” web app that can be used by web designers to construct web applications out of Polymer elements with styling that conforms to Google’s new generation user experience guidelines called Material Design. Web developers should probably start considering other professions because our skills may soon become obsolete ;-)

The goal of this chapter is to take a look at the polyfills, framework, and element libraries from Polymer from several angles, high level, detailed, critical, and pragmatic. The pragmatism is especially important. There is universal concensus among web developers that “web components” are the future of web development and should be highly promoted via projects like Polymer (and X-Tag from Mozilla) to help force widespread browser implementation. But how do we balance that with the reality that today the majority of enterprise organizations use Internet Explorer as their standard browser, and IE regards web component technologies as merely “under consideration” on its development roadmap?

The Polymer project, itself is still in a high state of flux with a consistent stream of breaking changes. For these reason we won’t dive too deeply into detailed examples of building a web component library or web application using Polymer as it is in “alpha” state, and will be for quite some time.

Platform.js - Web Components Polyfills

Platform.js, from the Polymer team, is the foundation for the Polymer framework. It provides cross-browser polyfills for all of the web component standards proposals we covered in the previous chapter including <template> tags, HTML imports, and the custom element and shadow DOM APIs. It also provides polyfills for ES6 WeakMap, DOM mutation observers, and web animations.

http://www.polymer-project.org/docs/start/platform.html

Web Animations are a separate W3C standard proposal that is meant to address deficiencies is the current web animation standards including CSS transitions, CSS animations, and SVG animations. More information on web animations can be found at:

http://dev.w3.org/fxtf/web-animations/

http://www.polymer-project.org/platform/web-animations.html

ES6 WeakMap will be a welcome addition to JavaScript. The dreaded memory leak in web applications occur because unused objects cannot be garbage collected until all reference keys to the object are destroyed. The problem is that hard references to an object can easily end up in places other than the primary reference, often as a side effect of using a UI framework such as jQuery to wrap a DOM object. WeakMap keys, on the other hand, do not prevent object garbage collection when the primary reference is destroyed. As newer versions of popular frameworks start using WeakMap for tracking objects, web developers will not need to be as meticulous in performing all the “clean up” steps when a chunk of the page is replaced during the normal lifecycle of an application.

Platform.js also provided support for “pointer events” which smooth out the differences between desktop hardware that uses mouse events and mobile hardware that uses touch events. However, that support quietly disappeared right around the time support for Web Animations was added. Now we should point out that Platform.js is a bundle of individual polyfills. You can still visit the GitHub repos for the Polymer project, grab any of the individual polyfills, and roll your own custom Platform.js. The advantage with this approach is you can create a much smaller file with just the polyfills that work correctly across browsers, and in most cases, leave out Web Animations.

http://www.polymer-project.org/resources/tooling-strategy.html#git

Browser Compatibility and Limitations

Recall in the previous chapter in code example 8.5 where we created an HTML document that demonstrated defining a custom element, and then creating a shadow DOM root and inserting <template> tag content into the shadow root as part of the element lifecycle. We did this using Chrome Canary with before and after screen shots that demonstrated the redistrabution of origin DOM nodes in the shadow tree.

To test how the Platform.js polyfills would stack up across current production browsers, we added:

<script src="bower_components/platform/platform.js"></script>

to the head of the same document and loaded it in Chrome 35, Firefox 30, and Safari 6.1.3 (desktop versions). We also tested the HTML Imports polyfill with another document that imported this document.

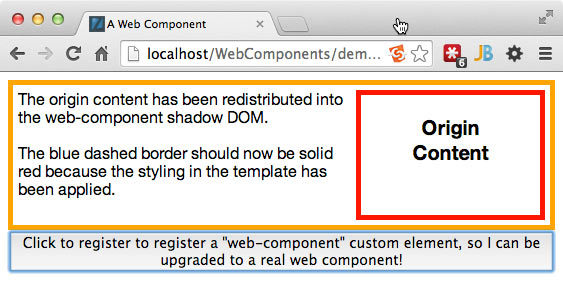

In Chrome 35 everything worked just as it did in Chrome Canary, and loading Platform.js was actually not necessary unless using HTML Imports. The custom element and shadow DOM APIs, plus <template> tag, are already implemented natively.

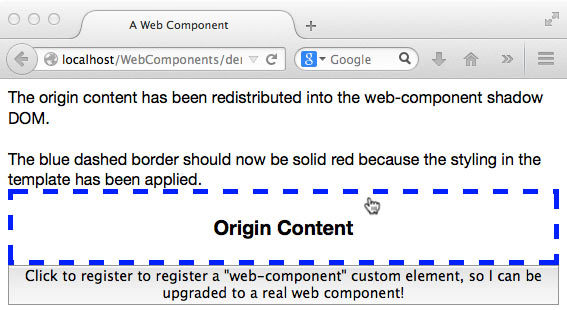

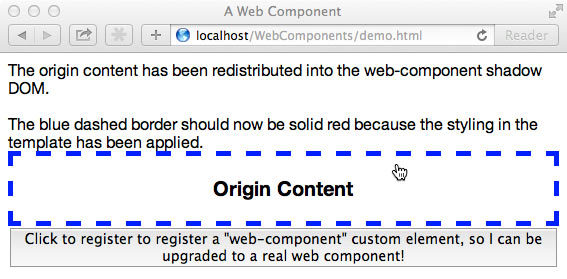

Unfortunately Firefox and Safari didn’t fare quite so well. The shim for HTML Imports worked (via AJAX). <template> tags are already first class elements as part of HTML5. The custom element polyfill appears to support the API. Inspection of the custom element reveals that it is indeed inheriting from HTMLElement which is what we specified. We did not test extension of existing elements. The shadow DOM basically polyfill failed, and predictably so.

Platform.js test in Chrome 35, shadow CSS is applied

Platform.js test in Firefox 30, shadow CSS is not applied

Platform.js test in Safari 6.1.3, shadow CSS is not applied

9.0 Shadow DOM CSS that cannot be polyfilled

<template id="web-component-tpl">

<style>

/* example of ::content pseudo element */

::content div {

/* this overrides the border property in page CSS */

border: 5px red solid;

width: 300px;

}

/* this pseudo class styles the web-component element */

:host {

display: flex;

height: 130px;

padding: 5px;

border: 5px orange solid;

font-size: 16px;

}

</style>

The origin content has been redistributed

into the web-component shadow DOM.

<br><br>

The blue dashed border should now be

solid red because the styling in the template

has been applied.

<!-- the new <content> tag where shadow host element

content will be "distributed" or transposed -->

<content></content>

</template>

As you can see from the Firefox and Safari screen grabs above, the CSS rules in the template content that is attached to the shadow root fail to be applied. The parent document CSS including the dashed blue border still applies. The pseudo class, :host, and the pseudo element, ::content, which should style the shadow host node and the content distribution node respectively, have no effect.

Keep in mind that this was

While this is unfortunate, it does make sense. JavaScript polyfills can only affect what they have access to. This includes all native JavaScript and DOM objects. JavaScript can affect the style properties of any individual node, but it can’t exert control over the recognition, influence or priority of CSS selectors. Only the native browser code, typically C++, has such control because CSS style application needs to happen at page rendering speed.

If we step back a bit and revisit the issues surrounding UI component encapsulation, you may recall that encapsulating CSS is the Achilles heel that prevents the construction of fully self-contained UI components. Even with the shadow DOM polyfill in Platform.js we still have the problem of CSS bleed across component boundaries whether web component or AngularJS UI component. This is the major reason for developer access to shadow DOM to begion with.

So here is what we can do usefully with Platform.js across browsers today (mid 2014). We can use <template> tags in Internet Explorer and we can use the custom element API to declare new elements with special purposes or extend existing elements with new functionality. HTML Imports are useful for the development of web components, but for a production application they need to be flattened for performance reasons.

Therefore, it is not surprising that the Polymer framework and the web component libraries (Polymer Core, Paper elements, X-Tag/Brick) are primarily built upon an architectural foundation of custom elements. The Polymer website maintains a browser compatibility matrix at:

http://www.polymer-project.org/resources/compatibility.html

Just keep in mind that a green rectangle could be interpreted as the Polymer team’s definition of support especially in regard to shadow DOM which is clearly limited to the DOM/JavaScript API methods. Also, keep in mind that until custom elements, shadow DOM, HTML imports, and Object.observe become web standards, they and Platform.js are subject to breaking changes.

From the point of view of a UI architect of enterprise grade, production web applications it would clearly not make sense to build a major new web application on a foundation like Platform.js which is in the state of “developer preview” according to the Polymer team. The purpose of highlighting this point is due to recent statements and hype from Google and the Polymer team that has come close to misrepresentation.

The Upside of Platform.js - Future Proofing Today’s Application

First, it is bummer that the previous sub-section had to be included. The reason for it is essentially due to professional responsibility (CYA) in evaluating new technology as a UI architect.

While the hype can be misleading to some less experienced web developers, it is also necessary in order to move web standards technology forward. In this regard, the Polymer team should get a standing ovation for their efforts. The educational and motivational value of the Platform.js polyfills, Chrome Canary, and Firefox Nightlies in turning on the web development community to these new standards is immense.

Every web developer who plans to be in this business three years from now should already be getting familiar with custom elements and shadow DOM APIs. It has practical value today in terms of structuring the code for current forms of UI components in such a way that it can be easily converted to take advantage of the web components APIs when ready. This includes managing the source code representations of behavior (JavaScript), structure (HTML templates), and presentation (LESS, SASS) together as a component, but separately within the component as a mini MVC application.

The advertising and hype about future technology is what counters the dead weight caused by archaic enterprise applications from companies like Oracle, SAP, and HP that keep legacy IE 6/7 from just going away. Even if Microsoft drags their feet on web components support they are now forced to acknowledge their lack of support:

The ability to create applications based on web components rather than just reading the W3C drafts, even if they only work fully on Chrome, can also be quite valuable in choosing JavaScript frameworks today. For example, consider frameworks that have already announced upgrade paths towards web component technologies in their roadmaps such as AngularJS or Ember. These frameworks let you style your source code in a web component friendly manner. In fact, this is the reason the first two-thirds of this book focus on building UI component libraries with AngularJS.

Now consider other frameworks such as ExtJS and the shiny new one from Facebook called React.js. The source code you would create with these frameworks will be anything but web component friendly. They tightly intermix and embed HTML generation deep within the core JavaScript, and they do not support two-way data binding. This tight coupling is well proven to hamper source code maintenance. React.js was developed by Facebook not so much to allow reactive programming style, but as a reaction to the performance problems caused by packing too much functionality into every page view of the Facebook application. Facebook’s use-case is far from the typical web application use-case.

As a UI architect, if I were tasked with designing an application architecture for something as monstrous as Facebook, then obviously AngularJS’ dirty-checking would not work, and I would consider React.js’ DOM “diffing” in order to get adequate performance out of the average browser used around the world. But for the average application my “go to” frameworks will those that support future technologies and best-practices.

Polymer.js

The Polymer team has named their framework after large molecules composed of many repeated monomers. The basic philosophy of Polymer is that everything is an element.

I suppose this makes sense if you are a chemical engineer. From the perspective of a web engineer this, technically, is a statement of fact given that all of the framework and application logic ends up in a <script> element eventually. The same goes for all of the CSS rules loaded by <link> or inhabiting <style> elements.

The only problem with facts is that they are not debatable, which is why we all the fun comes from having opinions. That’s what we are here to talk about. But first we need to understand what exactly comprises Polymer.js.

Polymer.js is the Google Polymer team’s web application framework that sits directly on top of platform.js. The purpose is to add a layer of convention and tools upon the web components proposals that makes them easier to use in composing a web application. The author’s opinion is that it is vital to have a solid understanding of the content and state of each of the underlying W3C standards drafts before spending time experimenting with Polymer.js. It’s tempting to skip this learning and go straight to the tutorial project on the Polymer website. The mistake in doing this is that your time spent will be uninformed. To put it another way, most web developers would probably prefer to be aware that there is a good chance that what is in the shadow DOM CSS proposals as of mid-2014 will not be the version that is actually accepted as a cross-browser standard. Having this sort of knowledge upfront can allow you to better divide your time between experimenting with the coming standards and producing with the current standards.

Know Where the Facts End and Opinions Begin

Another reason to gain a solid understanding of the W3C Web Components standard proposals prior to working with Polymer.js (or any other Web Component based framework) is to know where the browser standards end and the framework opinions begin. Having this understanding will allow you to make a more informed assessment as to the value the framework brings in fulfilling the business use case of your application.

Conceptually, Polymer.js provides three categories of tools and features. The first category are the usual set of web application tools provided by most modern JavaScript frameworks such as data-binding, custom events, and a version of OO style component extension. The second category are tools specific to building custom elements (components) with encapsulated logic, style, and content. The third category might be considered advertisements for other web standards proposals from Google, currently “web animations” and a one-size fits all event wrappers for normalizing mouse and touch events. The third category is not in the scope of this book.

The Usual Web Application Tools

Polymer.js provides web app construction tools very similar to AngularJS and other frameworks. Here’s a bullet list:

- Two-way data binding for “published properties” via {{ }} (mustache) syntax

- Declarative event mapping via on-event attributes to component functions

- Attribute or property value watchers

- Attribute or property group watchers

- Custom event bindings and triggers (publish and subscribe)

- Services wrapped as non-UI elements for commonalities like xhr and local storage

AngularJS uses an identical data binding syntax. Event bindings, individual and group watches, events triggers are all directly equivalent to AngularJS event directives like ngClick, $scope.$watch(‘value to watch’, callback), $scope.$watchGroup(), and $scope.$emit() and $scope.$broadcast() respectively.

A framework commonality that Polymer.js handles differently are application level services such as AJAX and local storage. Application and global services are typically implemented via some sort of service singleton. An example would be AngularJS’ $http service. This is where Polymer’s “everything is an element” philosophy ventures deeply into opinion. The Polymer opinion is that in order to develop an application the Polymer way you would either access the built-in global services by including and configuring the attributes of one of their core elements. Currently there are only a few, but it would be expected that for others, you would either create a custom element wrapper, or find one from a public component registry.

Everything is an Element

The author’s opinion of this approach is that it is misguided in the typical form of “this is the way the world should be” as opposed to the way things are for most web developers. To put it more concretely, the everything is an element notion would lead to a code maintenance nightmare. Consider again the approach taken by ExtJS where almost all of the rendered DOM is spit out from deep within their “configured” JavaScript objects- objects that extend other objects six or seven levels deep with a dozen or so lifecycle callbacks. When it comes time for a corporate re-branding, all of the JavaScript including the core library must be ripped apart to figure out where a <div> begins life or where a CSS classname is applied. It’s quite common for enterprise organizations in bad marriages with ExtJS to dedicate entire development teams to the task of restyling a couple pages. This all stems from the snake oil Sencha sells to non-technical executives that you can create web applications entirely via configuration, no front-end developers needed.

If everything is an element, then expect to start seeing HTML like the following:

<database-element initialize='{"name":"font-roboto","homepage":"https://github.c\

om/Polymer/font-roboto","version":"0.3.3","_release":"0.3.3","_resolution":{"typ\

e":"version","tag":"0.3.3","commit":"3515cb3b0d19e5df52ae8c4ad9606ab9a67b8fa6"},\

"_source":"git://github.com/Polymer/font-roboto.git","_target":"~0.3.3","_origin\

alSource":"Polymer/font-roboto","_direct":true}'>

Imagine an entire page full of elements like this …get the point?

HTML is a direct descendent of SGML which was developed specifically to provide a declarative syntax for defining the structure of a document, not the processing of a document. The whole point of declarative markup is to provide a document that is readable both by machines and people. The element above is neither declarative nor readable which makes it unmaintainable by default. This is why complex data attributes belong in a .json or .js file, not an .html file. By complex, we are referring to non-primitives which include objects, functions, and arrays. It’s the author’s opinion that primitive vs. complex attribute values should be solid dividing line that determine the appropriate location for maintaining data and logic. Along these lines, its not uncommon for AngularJS templates to cross the same line and become unreadable as an element declaration can span multiple lines when a half dozen directives are included.

Embedding application level logic within an element is no different than embedding element creation in JavaScript. While some standard elements like <meta>, <style>, <script> do not render to the display, they are generally very specific in terms of making a declaration about the document or loading a resource and the attribute APIs accept primitive types (boolean, string, and number).

The real point is not to bash on Polymer’s approach. Their ultimate goal is to publicize and educate the web community about coming web components standards that will benefit everyone instead of offering a serious web framework that would actually compete with the likes of AngularJS. This sub-section is the unfortunate by-product of a web architect calling out some bad architecture. The next section discusses some great ideas produced by the Polymer team for adding an abstraction layer to web components that make working with them more convenient and accessable for the average web developer.

<polymer-element> Declarative Custom Element Definitions

Recall in the previous chapter that according to the current state of W3C web components proposals you create a custom element by extending an existing HTMLElement prototype, adding lifecycle callback methods, and then calling document.registerElement(…) to finalize the element type for instantiation. In addition to this imperative method, the proposal also included a declarative method via the new <element> tag which proved not to be feasable a the browser native code level.

The Core

The Polymer framework still offers the declarative method of custom element definition via <polymer-element>, which is at the core of the framework. Under the covers, <polymer-element> API takes care of the imperative steps above, as well as encapsulating additional framework features, albiet, not at the browser native speed originally intended by the <element> W3C proposal. This is the skeleton example from the Polymer project website:

http://www.polymer-project.org/docs/polymer/polymer.html#element-declaration

<polymer-element name="tag-name" constructor="TagName">

<template>

<!-- shadow DOM here -->

</template>

<script>Polymer('tag-name');</script>

</polymer-element>

Polymer allows a few varients on the declaration process to allow source code maintenance flexability. The script can be referenced from an external resource either inside or outside the <polymer-element> tag, or not at all if the element is simple, static HTML and CSS. The Polymer() global JavaScript method can also be used for an imperative registration if desired.

For details on alternate element registration syntax, it’s best to refer directly to the Polymer API developer guide given the framework’s state of flux:

http://www.polymer-project.org/docs/polymer/polymer.html

In fact, when it comes to Polymer API details and syntax usage, we suggest your first resource is the official Polymer documentation. Most technical books on JavaScript frameworks have the luxury of discussing APIs that have matured and see production use throughout the Internet. So it is safe for them to include detailed API usage, and be resonably certain that it’s not likely to change for at least a year or two into the future.

When discussing pre-alpha technology, we don’t have such a luxury. Our approach must be to discuss such technology at a level of abstraction above exact syntactic detail in order to explain the concepts without becoming inaccurate within a few months. The concepts will last much longer than the details.

Attributes as API

This should sound familiar since AngularJS when used as a UI component library framework uses the same with custom element directives. <polymer-element> has a handful of “reserved” attributes for passing basic API parameters to the custom element declaration. Of these, name is currently the one that is required. The name attribute value becomes the name of the custom element and must include a hyphen in it to keep consistent with the document.registerElement() API. As mentioned previously, the prefix before the hyphen should be a unique three or more letters that distinguish your component library from others.

The extends attribute value would be any custom or built-in element to extend in an object oriented fashion. This API is optional, and is analogous to the document.registerElement({extends:’elem’}) parameter. With a <polymer-element extends="..."> definition, the parent element properties and methods are not just inherited, but also enhanced with data-binding unlike the standard registerElement().

Another object-oriented feature Polymer currently provides is the ability to invoke an overriden method via this.super() when called from within the method override of the extended element.

Use of the optional constructor attribute value results in a JavaScript contructor method for the custom element being placed on the global namespace. Users can then imperatively create element instances via the new ElemName() operator. If you inspect the global DOM object with your developer tools, you will see constructor methods for all of the standard HTML5 elements already available. Using the constructor=”ElemName” API just adds to the list.

The optional attributes attribute is a powerful way to include a space separated list of property names to be exposed as public properties or methods for configuring a custom-element instance. This is analogous to AngularJS’ attribute directives. Public element properties (attributes) declared this way get the benefit of two-way data-binding.

<polymer-element name="my-elem" attributes="name title age"> becomes

<my-elem name="Joe" title="president" age="19"> or

<my-elem name="{{dataName}}" title="{{dataTitle}}" age="{{dataAge}}">

The second my-elem instance has data-bound properties just like you might see in AngularJS markup. One difference is that any undeclared defaults are set to null in Polymer, whereas, they are undefined in AngularJS.

Just as Polymer offers an imperative method of custom element definition, so do they offer imperative public property definition via an object named “publish” on the second parameter to a call to Polymer(). Using the imperative option is currently the only way to set default values other than null for public properties.

Speaking of public property (HTML attribute) values, they all must be strings, and Polymer will attempt to deserialize to the appropriate JavaScript type such as boolean, number, array or object if not a string. It’s where the temptation to have attribute API transfer lengthy JSON arrays or object literals which leads to the anti-pattern displayed above of making “everything” an element. This is the case whether using Polymer, AngularJS, or any other declarative framework. HTML that becomes an unreadable mess full of JSON defeats the purpose of declarativeness. Do yourself a favor and avoid this temptation by using the rule-of-thumb that primatives can be handled declaratively and non-primitives should be handled imperatively.

The last and least of the optional attributes at this time of writing is noscript. It’s a boolean attribute, so there is no need to include it as noscript=”true”. Including the noscript attribute on a <polymer-element> declaration indicates that there is no need to invoke any JavaScript for all the Polymer bells and wistles on the element which is the default. You would use noscript in cases where all you need is an element with some custom HTML and CSS wrapped in a <template> tag, but no custom logic.

Lifecycle Callbacks

Polymer offers a superset of the of the custom element lifecycle callbacks that are part of the W3C specification which you would normally define on a custom element prototype object. The names are the same as the specification callbacks with the exception that they are shortened by dropping the “Callback” part in the Polymer:

ElemProto.createdCallback() ==> PolyElemProto.created()

ElemProto.attached Callback() ==> PolyElemProto.attached()

ElemProto.detachedCallback() ==> PolyElemProto.detached()

ElemProto.attributeChangedCallback() ==> PolyElemProto.attributeChanged()

Polymer element definitions provide two additional callback methods specific to lifecycle states of the framework code execution not included in the W3C specfication. The ready() callback is executed in between the created() and attached() callbacks. More specifically, ready() is called when all of the Polymer framework tasks beyond simple instantiation of an element have concluded including Shadow DOM creation, data-binding setup and event listener setup, but the element has yet to be inserted into the browser DOM. You might use this callback to provide any modifications or addtions to the Polymer framework tasks.

The domReady() callback is executed after the attached() callback and after any child elements within the custom element have been attached to the DOM and are ready for any interaction. This is analogous to when AngularJS would call the postLink() method during a directive lifecycle. Therefore, you would include logic in this callback which depends on a Polymer element hierarchy that is attached to the DOM and is functional.

At the top of the Polymer element hierarchy in the DOM there is the polymer-ready event that is fired by the framework when all custom Polymer elements in the DOM have been registered and upgraded from HTMLUnknownElement status. If you needed to interact with Polymer elements from outside of the framework, you would set up a listener via something typical like:

window.addEventListener('polymer-ready', evtHandlerFn);

Other Polymer Framework API Features

Wrapping a custom element with the Polymer framework is in many ways similar to wrapping a common element with jQuery. You get all kinds of stuff you may or may not need. We will run through the list briefly and refer you to the official documentation for exact details of Polymer’s implementation at the time of reading.

The Polymer API includes a method for observing mutations to child elements:

/*custom element instance*/ this.onMutation(childElem, callbackFn)

Also included in the custom element declaration API are inline event handler declarations with a syntax of on-eventname="{{eventHandler}}". There is nothing special here. The idea is the same as AngularJS built-in event directives such as ng-click="handlerFn". Rather than provide the handler function on the $scope object in the AngularJS controller, you provide the matching handler in the element configuration object.

You can also set the equivalent to AngularJS $scope.$watch('propertyName', callbackFn) by defining a function on the configuration object and following their convention that adds “Changed” to the property name followed by the function definition:

<polymer-element attributes="age" ...>

customElemConfigObj.ageChanged = function(oldVal, newVal){...}

They’ve even copied the $scope.$watchGroup() method from AngularJS and renamed it observe = {object of properties}.

Custom events can be triggered using:

/*custom element instance*/ this.fire('eventName', paramsObj);

Template nodes with id attributes can be referenced via the $ hash like so:

<input type="text" id="elemId">

/*custom element instance*/ this.$.elemId;

Polymer’s version of AngularJS’ $timeout service or window.setTimeout is called job:

/*custom element instance*/ this.job('jobName', callbackFn, delayInMS);

Polymer and <template> Tags with Data Binding

According to the Polymer documentation, the contents of an outer <template> tag within a Polymer element definition will become the tag’s shadow DOM upon instantiation. Any nested <template> tags can make use of a limited set of logic found in most UI template libraries like Handlebars.js, or certain AngularJS directives. Here are the available template functions at the time of writing along with the AngularJS equivalents:

Iterating over an array with Polymer:

<template repeat="{{item in menuItems}}">

<li><a href="{{item.url}}">{{item.text}}</a></li>

</template>

AngularJS:

<li ng-repeat="item in menuItems"><a href="{{item.url}}">{{item.text}}</a></li>

Binding a View-Model object to <template> contents with Polymer:

<template bind="{{menuItem}}">

<li><a href="{{ menuItem.url}}">{{ menuItem.text}}</a></li>

</template>

AngularJS:

<li ng-controller="menuItemCrtl"><a href="{{menuItem.url}}">{{menuItem.text}}</a></li>

This assumes the controller has an associated $scope.menuItem object. Template binding with AngularJS can also be more granular or specialized with ngBind for a single datum or ngBindTemplate for multiple $scope values.

Conditional inclusion with Polymer:

<template if="{{someValueIsTrue}}">

<span>insert this</span>

</template>

AngularJS:

<span ng-if="someValueIsTrue">insert this</span>

Conditional attributes with Polymer:

<input type="checkbox" checked?="{{booleanValue}}">

AngularJS:

<input type="checkbox" ng-checked="booleanValue">

Polymer and AngularJS have almost identical pipe syntax “|” for filtering value or expression output. The major difference between the frameworks is that AngularJS filters are defined as modules that can be dependency injected anywhere in the application, whereas, Polymer filters must be defined on the custom element object. So it is unclear with Polymer how you would go about sharing a filter among different element types other than by referencing a global.

Speaking of globals, the Polymer documentation “suggests” that in keeping with their opinion that “everything is an element” any application or global level functionality or data should be defined as a custom element. In other words, the framework has no concept of models or controllers because everything is part of the view. Does anyone remember IE5 or earlier where you could make proprietary database queries directly in your markup? We’ll discuss the issue of UI patterns and anti-patterns in a later section.

You may have noticed that in cases where Polymer uses the <template> tag for binding a data scope, conditional or iterator, AngularJS does the same with a directive directly on the contained element. This is unfortunate in Polymer’s case because not only does this dependency typically result in two extra lines of source code, but it also adds another cross browser incompatibility. Internet Explorer will not be standards complient in supporting the <template> tag until IE 13 at the earliest. This means that on that platform any template content that references external assets will try to resolve them prematurely, and you would not be able to handle one of the most common iterator situations which is repeating <tr> table row elements inside a <table> tag. Polymer’s “workaround” which is to include a “template” and a “repeat” attribute directly on a <tr> tag is unacceptable from a code maintenance standpoint.

This rounds out discussion of the Polymer framework features worth mentioning. This is not to say the other features are worthless. They just do not directly enhance the Web Components specifications or fill in the gaps that will still be there when Web Components are widely implemented. Left out of the discussion are “Layout Attributes” since they are labeled as experimental as of this writing. The shadow DOM styling hacks in polymer.js result in slightly better encapsulation than just the “polyfill” in platform.js, but the source is not maintainable. Finally, “touch and gesture” events which used to be called “pointer” events are a seperate early specification proposal from Google the Polymer team is trying to promote with the framework.

Stepping back to a big picture view of Polymer again it should be clearer that pros of the framework are that it promotes education and experimentation with Web Components specification proposals which is very helpful in influencing the web developer community to demand that all browser vendors move towards standardization and implementation. Polymer also does a good job elucidating the gaps in the specification that frameworks will still need to cover in order to build truely full featured, high quality UI components and libraries.

The most glaring con of Polymer is that it just is not, nor will it be, a UI framework suitable for serious enterprise production applications as long as it promotes anti-patterns, disregards established front-end patterns, and ignores certain basic realities of all the browser platforms in substantial use now and likely to be in substantial use in the near future.

Polymer Element Libraries

Comming soon.

Core Elements

Comming soon.

Paper Elements

Comming soon.

Mozilla X-Tags

Comming soon.