Chapter 5 - Standalone UI Components by Example

In part one we presented a good deal of discussion concerning UI component architecture and the tools that AngularJS provides for building and encapsulating reusable UI components. However, discussion only gets us so far, and in UI development, is not very useful without corresponding implementation examples. In this chapter we will examine a hypothetical use-case that can be addressed with a discreet UI component that is importable, configurable, and reusable.

“As a web developer for a very large enterprise organization I need to be able to quickly include action buttons on my microsite that adhere to corporate style guide standards for color, shape, font, etc, and can be configured with the necessary behavior for my application.”

Most enterprise organizations have strict branding guidelines that dictate specifications for the look and feel of any division microsites that fall under the corporate website domain. The guidelines will normally cover such item as typography, colors, logo size and placement, navigation elements and other common UI element styles in order to provide a consistent user experience across the entire organization’s site. Organizations that don’t enforce their global style guides end up with websites from one division to the next that can be very different both visually and behaviorally. This gives the impression to the customer that one hand of the organization doesn’t know what the other hand is doing.

For a web developer in any corporate division, the task is usually left to them to create an HTML element and CSS structure that adheres to the corporate style guide which can be time consuming and detract from the task at hand. Some of the UI architects in the more web savvy organizations have made the propagation of the corporate look and feel easier for individual development teams by providing UI component pallets or menus that contain prefabricated common UI elements and components complete with HTML, CSS, images, and JavaScript behavior. A good analogy would be the CSS and JavaScript components included as part of Twitter’s Bootstrap.

A proprietary framework often used for the above is ExtJS. Underneath ExtJS is a lot of monolithic JavaScript and DOM rewriting. It works great if used as is out of the box, but breaks down severely when styling or behavior modifications are needed. It also has serious performance problems and does not play well with other toolkits and frameworks. Such has been the price for providing customized HTML through JavaScript hacking, when the ability to create custom HTML should be available in native HTML and browser DOM methods.

AngularJS gives us the tools to create pre-built, custom HTML components in a much more declarative and natural way as if we were extending existing elements, and in a way more in line with the W3C proposed set of Web Components standards. An added advantage is much less intrusiveness towards other toolkits and frameworks.

Our example component will be, in essence, an extension to the HTML <button> element. We will extend it to include our corporate styling (Bootstrap.css for sake of familiarity) plus additional attributes that will serve as the element’s API in the same way as existing HTML elements. We will name it “smart-button” and developers will be able to include it in their markup as <smart-button> along with any desired attributes. The smart-button’s available attributes will allow any necessary information to be passed in, and give the button the ability to perform various, custom actions upon click. There is a lot of things a smart button could do: fire events, display pop-up messages, conditional navigation, and handle AJAX requests to name a few. This will be accomplished with as much encapsulation that AngularJS directives will allow, and with minimal outside dependencies.

While creating a “button” component might not be very complex, clever, or sexy, the point is actually to keep the functionality details reasonably simple and focus more on the methods of encapsulation, limiting hard dependencies via dependency injection and pub-sub, while providing re-usability, portability, and ease of implementation.

Building a Smart Button component

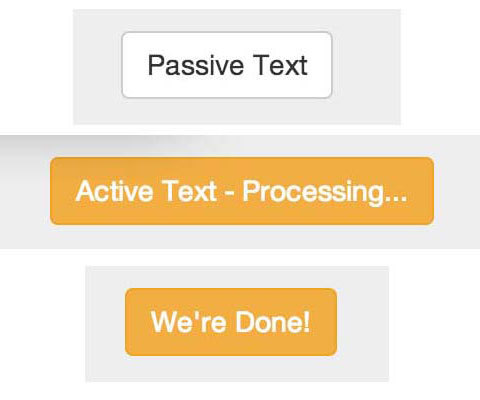

Various states of our smart button

We’ll start with a minimal component directive, and use Twitter’s Bootstrap.css as the base set of available styles. The initial library file dependencies will be the most recent, stable versions of angular.min.js and bootstrap.min.css. Create a root directory for the project that can be served via any web server, and then we will wrap our examples inside Bootstrap’s narrow jumbotron. Please use the accompanying GitHub repo for working code that can be downloaded. As we progress, we will build upon these base files.

5.0 Smart Button starter directories

/project_root

smart_button.html

/js

UIComponents.js

SmartButton.js

/lib

angular.min.js

bootstrap.min.css

5.1 Smart Button starter HTML

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html ng-app="UIComponents">

<head>

<title>A Reusable Smart Button Component</title>

<link href="./lib/bootstrap.min.css" rel="stylesheet">

<script src="./lib/angular.min.js"></script>

</head>

<body>

<div class="jumbotron">

<h1>Smart Buttons!</h1>

<p><!-- static markup version -->

<a class="btn btn-default">Dumb Button</a>

</p>

<p><!-- dynamic component version-->

<smart-button></smart-button>

</p>

</div>

<script src="./js/UIComponents.js"></script>

<script src="./js/SmartButton.js"></script>

</body>

</html>

5.2 Smart Button starter JavaScript

// UIComponents.js

(function(){

'use strict';

// this just creates an empty Angular module

angular.module('UIComponents',[]);

})();

// SmartButton.js directive definition

(function(){

'use strict';

var buttons = angular.module('UIComponents');

buttons.directive('smartButton', function(){

var tpl = '<a ng-class="bttnClass">{{defaultText}}</a>';

return {

// use an inline template for increaced

template: tpl,

// restrict directive matching to elements

restrict: 'E',

// replace entire element

replace: true,

// create an isolate scope

scope: {},

controller: function($scope, $element, $attrs){

// declare some default values

$scope.bttnClass = 'btn btn-default';

$scope.defaultText = 'Smart Button';

},

link: function(scope, iElement, iAttrs, controller){}

};

});

})();

If we load the above HTML page in a browser, all we see are two very basic button elements that don’t do anything when clicked. The only difference is that the first button is plain old static html, and the second button is matched as a directive and replaced with the compiled and linked template and scope defaults.

Naming our component “smart-button” is for illustrative purposes only. It is considered a best-practice to prepend a distinctive namespace of a few letters to any custom component names. If we create a library of components, there is less chance of a name clash with components from another library, and if multiple component libraries are included in a page, it helps to identify which library it is from.

Directive definition choices

In-lining templates

There are some things to notice about the choices made in the directive definition object. First, in an effort to keep our component as self-contained as possible, we are in-lining the template rather than loading from a separate file. This works in the source code if the template string is at most a few lines. Anything longer and we would obviously want to maintain a separate source file for the template html, and then in-line it during a production build process.

In-lining templates in source JavaScript does conflict with any strategy that includes maintaining source code in a way that is forward compatible with web components structure. When the HTML5 standard <template> tag is finally implemented by Internet Explorer, the last holdout, then all HTML template source should be maintained in <template> tags.

Restrict to element

Next, we are restricting the directive matching to elements only since what we are doing here is creating custom HTML. Doing this makes our components simple for designers or junior developers to include in a page especially since the element attributes will also serve as the component API.

Create an Isolate Scope

Finally, we set the scope property to an empty object,{}. This creates an isolate scope that does not inherit from, is not affected by, or directly affects ancestor AngularJS scopes. We do this since one of the primary rules of component encapsulation is that the component should be able to exist and function with no direct knowledge of, or dependency on the outside world.

Inline Controller

In this case we are also in-lining the code for the component’s primary controller. Just like the inline template, we are doing this for increased encapsulation. The in-lined controller function should contain code, functions and default scope values that would be common to all instances of that particular type of directive. Also, just like with the templates, controllers functions of more than a few lines would likely best be maintained in a separate source code file and in-lined into the directive as part of a build process.

As a best-practice (in this case, DRY or don’t repeat yourself), business logic that is common to different types of components on your pallet should not be in-lined, but “required” via the require attribute in the definition object. As this does cause somewhat of an external dependency, use of required controllers should be restricted to situations where groups of components from the same vendor or author that use the logic are included together in dependency files. An analogy would be the required core functionality that must be included for any jQuery UI widget.

One thing of note, as of this writing, the AngularJS docs for $compile mention the use of the controllerAs attribute in the definition object as useful in cases where directives are used as components. controllerAs allows a directive template to access the controller instance (this) itself via an alias, rather than just the $scope object as is typical. There are different opinions, and a very long thread discussing this in the AngularJS Google group. By using this option, what is essentially happening is that the view is gaining direct access to the business logic for the directive. I lean toward the opinion that this is not really as useful for directives used as components as it is for junior developers new to AngularJS and not really familiar with the benefits of rigid adherence to MVVM or MV* patterns. One of the primary purposes of $scope is to expose the bare minimum of logic to view templates as the views themselves should be kept as dumb as possible.

Another thing that should be thoroughly understood is that variables and logic that are specific to any instance of a directive, especially those that are set at runtime should be located in the link function since that is executed after the directive is matched and compiled. For those with an object oriented background, an analogy would be the controller function contents are similar to class variables and functions, whereas, the link function contents are similar to the instance variables and functions.

Attributes as Component APIs

It’s often said that an API (application programmer interface) is the contract between the application provider and the application consumer. The contract specifies how the consumer can interact with the application via input parameters and returned values. Note that a component is really a mini application, so we’ll use the term component from now on. What is significant about the contract is that there is a guarantee from the provider that the inputs and outputs will remain the same even if the inner workings of the component change. So while the provider can upgrade and improve parts of the component, the consumer can be confident that these changes will not break the consuming application. In essence, the component is a black box to the consumer.

Web developers interact with APIs all the time. One of the largest and most used APIs is that provided by the jQuery toolkit. But the use of jQuery’s API pales in comparison to the most used API in web development, which is the API provided by the HTML specification itself. All major browsers make this API available by default. To specifically use the HTML5 API we can start an HTML document with <!DOCTYPE html>.

Attributes Aren’t Just Function Parameters and Return Values

Many web developers are not aware of it, but DOM elements from the browser’s point of view are actually components. Underneath the covers many DOM elements encapsulate HTML fragments that are not directly accessible to the developer. These fragments are known as shadow DOM, and we will be hearing quite a lot about this in the next few years. We will also take an in-depth look at shadow DOM later in this book. <input type="range"> elements are a great example. Create or locate an HTML document with one of these elements, and in Chrome developer tools check the Shadow Dom box in settings, and click on the element. It should expand to show you a greyed out DOM fragment. We cannot manipulate this DOM fragment directly, but we can affect it via the element attributes min, max, step and value. These attributes are the element’s API for the web developer. Element attributes are also the most common and basic way to define an API for a custom AngularJS component.

Our smart button component really isn’t all that smart just yet, let’s start building our API to add some usefulness for the consumers of our component.

5.3 Adding a button text API

<!-- a custom attribute allowing text manipulation -->

<smart-button default-text="A Very Smart Button"></smart-button>

link: function(scope, iElement, iAttrs, controller){

// <string> button text

if(iAttrs.defaultText){

scope.defaultText = iAttrs.defaultText;

}

}

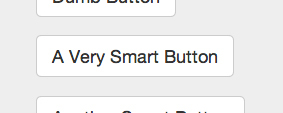

Screen grab of the “default-text” attribute API

The code additions in bold illustrate how to implement a basic custom attribute in an AngularJS component directive. Two things to note are that AngularJS auto camel-casing applies to our custom attributes, not just those included with AngularJS core. The other is the best-practice of always providing a default value unless a certain piece of information passed in is essential for the existence and basic functioning of our component. In the case of the later, we still need to account situations where the developer forgets to include that information and fail gracefully. Otherwise, AngularJS will fail quite un-gracefully for the rest of the page or application.

Now we’ve given the consumer of our component the ability to pass in a default string of text to display on our still not-to-smart button. This alone is not an improvement over what can be done with basic HTML. So, let’s add another API option that will be quite a bit more useful.

5.4 Adding an activetext API option

<!-- notice how simple and declarative our new element is -->

<smart-button

default-text="A Very Smart Button"

active-text="Wait for 3 seconds..."

></smart-button>

(function(){

'use strict';

var buttons = angular.module('UIComponents');

buttons.directive('smartButton', function(){

var tpl = '<a ng-class="bttnClass" '

+ 'ng-click="doSomething()">{{bttnText}}</a>';

return {

// use an inline template for increased encapsulation

template: tpl,

// restrict directive matching to elements

restrict: 'E',

replace: true,

// create an isolate scope

scope: {},

controller: function($scope, $element, $attrs, $injector){

// declare some default values

$scope.bttnClass = 'btn btn-default';

$scope.bttnText = $scope.defaultText = 'Smart Button';

$scope.activeText = 'Processing...';

// a nice way to pull a core service into a directive

var $timeout = $injector.get('$timeout');

// on click change text to activeText

// after 3 seconds change text to something else

$scope.doSomething = function(){

$scope.bttnText = $scope.activeText;

$timeout(function(){

$scope.bttnText = "We're Done!";

}, 3000);

};

},

link: function(scope, iElement, iAttrs, controller){

// <string> button text

if(iAttrs.defaultText){

scope.bttnText = scope.defaultText = iAttrs.defaultText;

}

// <string> button text to diplay when active

if(iAttrs.activeText){

scope.activeText = iAttrs.activeText;

}

}

};

});

})();

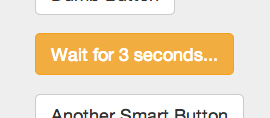

We have now added an API option for text to display during a temporary active state, a click event handler to switch to the active state for three seconds and display the active text, and injected the AngularJS $timeout service. After three seconds, the button text displays a “finished” message.

You can give it a run in a browser to see the result, and you definitely cannot do this with standard HTML attributes. While we are essentially just setting a delay with setTimout(), this would be the same pattern if we were to fire an AJAX request with the $http service. Both service functions return a promise object whose success() and error() function callbacks can execute addition logic such as displaying the AJAX response value data upon success, or a failure message upon an error. In the same way we’ve created an API for setting text display states, we could also create API attribute options for error text, HTTP configuration objects, URLs, alternative styling, and much more.

Screen grab of the “active-text” attribute API

Take a look at the HTML markup required to include a smart button on a page. It’s completely declarative, and simple. No advanced JavaScript knowledge is required, just basic HTML making it simple for junior engineers and designers to work with.

Events and Event Listeners as APIs

Another basic way to keep components independent of outside dependency is to interact using the observer, or publish and subscribe pattern. Our component can broadcast event and target information, as well as, listen for the same and execute logic in response. Whereas element attributes offer the easiest method for component configuration by page developers, events and listeners are the preferred way of inter-component communication. This is especially true of widget components inside of a container component as we will explore in the next chapter.

Recall that AngularJS offers three event methods: $emit(name, args), $broadcast(name, args), and $on(name, listener). Discreet components like the smart button will most often use $emit and $on. Container components would also make use of $broadcast as we will discuss in the next chapter. Also, recall from earlier chapters that $emit propagates events up the scope hierarchy eventually to the $rootScope, and $broadcast does the opposite. This holds true even for directives that have isolate scopes.

A typical event to include in our API documentation under the “Events” section would be something like “smart-button-click” upon a user click. Other events could include “on-success” or “on-failure” for any component generated AJAX calls, or basically anything related to some action or process that the button handles. Keep in mind that a $destroy event is always broadcasted upon scope destruction which can and should be used for any binding cleanup.

5.5 Events and Listeners as Component APIs

// UIComponents.js

(function(){

'use strict';

angular.module('UIComponents',[])

.run(['$rootScope', function($rootScope){

// let's change the style class of a clicked smart button

$rootScope.$on('smart-button-click', function(evt){

// AngularJS creates unique IDs for every instantiated scope

var targetComponentId = evt.targetScope.$id;

var command = {setClass: 'btn-warning'};

$rootScope

.$broadcast('smart-button-command', targetComponentId, command);

});

}]);

})();

(function(){

'use strict';

var buttons = angular.module('UIComponents');

buttons.directive('smartButton', function(){

var tpl = '<a ng-class="bttnClass" '

+ 'ng-click="doSomething(this)">{{bttnText}}</a>';

return {

// use an inline template for increased encapsulation

template: tpl,

// restrict directive matching to elements

restrict: 'E',

replace: true,

// create an isolate scope

scope: {},

controller: function($scope, $element, $attrs, $injector){

// declare some default values

$scope.bttnClass = 'btn btn-default';

$scope.bttnText = $scope.defaultText = 'Smart Button';

$scope.activeText = 'Processing...';

// a nice way to pull a core service into a directive

var $timeout = $injector.get('$timeout');

// on click change text to activeText

// after 3 seconds change text to something else

$scope.doSomething = function(elem){

$scope.bttnText = $scope.activeText;

$timeout(function(){

$scope.bttnText = "We're Done!";

}, 3000);

// emit a click event

$scope.$emit('smart-button-click', elem);

};

// listen for an event from a parent container

$scope.$on('smart-button-command', function(evt,

targetComponentId, command){

// check that our instance is the target

if(targetComponentId === $scope.$id){

// we can add any number of actions here

if(command.setClass){

// change the button style from default

$scope.bttnClass = 'btn ' + command.setClass;

}

}

});

},

link: function(scope, iElement, iAttrs, controller){

// <string> button text

if(iAttrs.defaultText){

scope.bttnText = scope.defaultText = iAttrs.defaultText;

}

// <string> button text to diplay when active

if(iAttrs.activeText){

scope.activeText = iAttrs.activeText;

}

}

};

});

})();

In the bold sections of the preceding code, we added an event and an event listener to our button API. The event is a basic onclick event that we have named “smart-button-click”. Now any other AngularJS component or scope that is located on an ancestor element can listen for this event, and react accordingly. In actual practice, we would likely want to emit an event that is more specific to the purpose of the button since we could have several smart buttons in the same container. We could use the knowledge that we gained in the previous section to pass in a unique event string as an attribute on the fly.

The event listener we added also includes an event name string plus a unique ID and command to execute. If a smart button instance receives an event notification matching the string it checks the included $scope.$id to see if there is a match, and then checks for a match with the command to execute. Specifically in this example, if a “setClass” command is received with a value, then the smart button’s class attribute is updated with it. In this case, the command changes the Bootstrap button style from a neutral “btn-default” to an orange “btn-warning”. If the consumers of our component library are not technical, then we likely want to keep use of events to some specific choices such as setting color or size. But if the consumers are technical, then we can create the events API for our components to allow configurable events and listeners.

One item to note for this example is that our component is communicating with the AnguarJS instance of $rootScope. We are using $rootScope as a substitute for a container component since container components will be the subject of the next chapter. The $rootScope in an AngularJS application instance is similar conceptually to the global scope in JavaScript, and this has pros and cons. One of the pros is that the $rootScope is always guaranteed to exist, so if all else fails, we can use it to store data, and functions that need to be accessed by all child scopes. In other words, any component can count on that dependency always being there. But the con is that it is a brittle dependency from the standpoint that other components from other libraries have access and can alter values on it that might conflict with our dependencies.

Advanced API Approaches

Until now we have restricted our discussion of component APIs to attribute strings and events, which are most common and familiar in the web development world. These approaches have been available for 20 years since the development of the first GUI web browsers and JavaScript, and cover the vast majority of potential use-cases. However, some of the tools provided by AngularJS allow us to get quite a bit more creative in how we might define component APIs.

Logic API options

One of the more powerful features of JavaScript is its ability to allow us to program in a functional style. Functions are “first-class” objects. We can inject functions via parameters to other functions, and the return values of functions can also be functions. AngularJS allows us to extend this concept to our component directive definitions. We can create advanced APIs that require logic as the parameter rather than just simple scalar values or associative arrays.

One option for using logic as an API parameter is via the scope attribute of a directive definition object with &attr:

scope: {

functionCall: & or &attrName

}

This approach allows an AngularJS expression to be passed into a component and executed in the context of a parent scope.

5.6 AngularJS Expressions as APIs

<!-- index.html -->

<smart-button

default-text="A Very Smart Button"

active-text="Wait for 3 seconds..."

debug="showAlert('a value on the $rootScope')"

></smart-button>

// UIComponents.js

(function(){

'use strict';

angular.module('UIComponents',[])

.run(['$rootScope', '$window', function($rootScope, $window){

// let's change the style class of a clicked smart button

$rootScope.$on('smart-button-click', function(evt){

// AngularJS creates unique IDs for every instantiated scope

var targetComponentId = evt.targetScope.$id;

var command = {setClass: 'btn-warning'};

$rootScope.$broadcast('smart-button-command', targetComponentId,

command);

});

$rootScope.showAlert = function (message) {

$window.alert(message);

};

}]);

})();

// SmartButton.js

(function(){

'use strict';

var buttons = angular.module('UIComponents');

buttons.directive('smartButton', function(){

var tpl = '<a ng-class="bttnClass" '

+ 'ng-click="doSomething(this);debug()">{{bttnText}}</a>';

return {

template: tpl, // use an inline template for increaced

restrict: 'E', // restrict directive matching to elements

replace: true,

// create an isolate scope

scope: {

debug: '&'

},

controller: function($scope, $element, $attrs, $injector){

// declare some default values

$scope.bttnClass = 'btn btn-default';

$scope.bttnText = $scope.defaultText = 'Smart Button';

$scope.activeText = 'Processing...';

// a nice way to pull a core service into a directive

var $timeout = $injector.get('$timeout');

// on click change text to activeText

// after 3 seconds change text to something else

$scope.doSomething = function(elem){

$scope.bttnText = $scope.activeText;

$timeout(function(){

$scope.bttnText = "We're Done!";

}, 3000);

// emit a click event

$scope.$emit('smart-button-click', elem);

};

// listen for an event from a parent container

$scope.$on('smart-button-command', function(evt,

targetComponentId, command){

// check that our instance is the target

if(targetComponentId === $scope.$id){

// we can add any number of actions here

if(command.setClass){

// change the button style from default

$scope.bttnClass = 'btn ' + command.setClass;

}

}

});

},

link: function(scope, iElement, iAttrs, controller){

// <string> button text

if(iAttrs.defaultText){

scope.bttnText = scope.defaultText = iAttrs.defaultText;

}

// <string> button text to diplay when active

if(iAttrs.activeText){

scope.activeText = iAttrs.activeText;

}

}

};

});

})();

The bold code in our contrived example shows how we can create an API option for a particular debugging option. In this case, the “debug” attribute on our component element allows our component to accept a function to execute that helps us to debug via an alert() statement. We could just as easily use the “debug” attribute on another smart button to map to a value that includes logic for debugging via a “console.log()” statement instead.

Another strategy for injecting logic into a component directive is via the require: value in a directive definition object. The value is the controller from another directive that contains logic meant to be exposed. A common use case for require is when a more direct form of communication between components than that offered by event listeners is necessary such as that between a container component and its content components. A great example of such a relationship is a tab container component and a tab-pane component. We will explore this usage further in the next chapter on container components.

View API Options

We have already seen examples where we can pass in string values via attributes on our component element, and we can do the same with AngularJS expressions, or by including the “require” option in a directive definition object. But AngularJS also gives us a way to create a UI component whose API can allow a user to configure that component with an HTML fragment. Better yet, that HTML fragment can, itself, contain AngularJS directives that evaluate in the parent context similar to how a function closure in JavaScript behaves. The creators of AngularJS have made up their own word, Transclusion, to describe this concept.

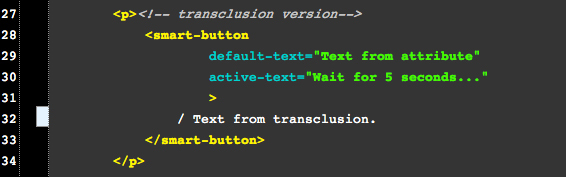

5.7 HTML Fragments as APIs - Transclusion

<!-- index.html -->

<smart-button

default-text="Text from attribute"

active-text="Wait for 5 seconds..."

>

Text from transclusion.

</smart-button>

// SmartButton.js

(function(){

'use strict';

var buttons = angular.module('UIComponents');

buttons.directive('smartButton', function(){

var tpl = '<a ng-class="bttnClass"'

+ 'ng-click="doSomething(this);debug()">{{bttnText}} '

+'<span ng-transclude></span></a>';

return {

template: tpl, // use an inline template for increaced

restrict: 'E', // restrict directive matching to elements

replace: true,

transclude: true,

// create an isolate scope

scope: {

debug: '&'

},

controller: function($scope, $element, $attrs, $injector){

...

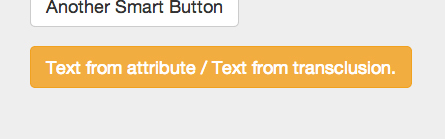

Screen shot of Smart Button component with a transcluded text node

The pre-compiled HTML markup utilizing element contents as an API

While this example is about as minimalist as you can get with transclusion, it does show how the inner HTML (in this case, a simple text node) of the original component element can be transposed to become the contents of our compiled directive. Note that the ngTransclude directive must be used together with transclude:true in the component directive definition in order for transclusion to work.

When working with a button component there really isn’t a whole lot that you would want to transclude, so the example here is just to explain the concept. Transclusion becomes much more valuable for the component developer who is developing UI container components such as tabs, accordions, or navigation bars that need to be filled with content.

The Smart Button Component API

Below is a brief example of an API we might publish for our Smart Button component. In actual practice, you’d want to be quite a bit more descriptive and detailed in usage with matching examples, especially if the intended consumers of your library are anything other than senior web developers. Our purpose here is to provide the “contract” that we will verify with unit test coverage at the end of this chapter.

COMPONENT DIRECTIVE: smartButton

USAGE AS ELEMENT:

<smart-button

default-text="initial button text to display"

active-text="text to display during click handler processing"

debug="AngularJS expression"

>

"Transclusion HTML fragment or text"

</smart-button>

ARGUMENTS:

| Param | Type | Details |

|---|---|---|

| defaultText | string | initial text content |

| activeText | string | text content during click action |

| debug | AngularJS | expression |

| transclusion | content | HTML fragment |

EVENTS:

| Name | Type | Trigger | Args |

|---|---|---|---|

| ‘smart-button-click’ | $emit() | ngClick | element |

| ‘smart-button-command’ | $on() |

What About Style Encapsulation?

We mentioned earlier in this book that what makes discreet UI components valuable for large organizations with very large web sites or many microsites under the same domain is the ability to help enforce corporate branding or look-and-feel throughout the entire primary domain. Instead of relying on the web developers of corporate microsites to adhere to corporate style guides and standards on their own, they can be aided with UI component pallets or menus whose components are prebuilt with the corporate look-and-feel.

While all the major browsers, as of this writing, allow web developers to create UI components with encapsulated logic and structure whether using AngularJS as the framework or not, none of the major browsers allow for the same sort of encapsulation when it comes to styling, at least not yet. The current limitation with developer supplied CSS is that there is no way to guarantee 100% that CSS rules intended to be applied only to a component will not find their way into other parts of the web document, or that global CSS rules and styles will not overwrite those included with the component. The reality is that any CSS rule that appears in any part of the web document has the possibility to be matched to an element anywhere in the document, and there is no way to know if this will happen at the time of component development.

When the major browsers in use adopt the new standards for Web Components, specifically Shadow DOM, style encapsulation will be less of a concern. Shadow DOM will at least prevent component CSS from being applied beyond the component’s boundaries, but it is still unknown if the reverse will be true as well. Best guess would be probably not.

|

08/18/2014 update - special CSS selectors are planned (unfortunately) that will allow shadow DOM CSS to be applied outside the encapsulation boundary. Conversely, global CSS will NOT traverse into shadow DOM (thankfully) unless special pseudo classes and combinators are used. |

Style Encapsulation Strategies

The best we can do is to apply some strategies with the tools that CSS provides to increase the probability that our components will display with the intended styling. In other words, we want to create CSS selectors that will most likely have the highest priority of matching just the elements in our components.

If style encapsulation is a concern, then a thorough understanding of CSS selector priority is necessary, but beyond the scope of this book. However, what is relevant to mention here is that styles that are in-lined with an element or selectors post-fixed with “!important” generally win. The highest probability that a selector will be applied is one that is in-lined and has “!important” post-fixed. For up to a few style rules this can be used. But it becomes impractical for many rules.

For maintaining a component style sheet, the suggestion would be to use a unique class or ID namespace for the top level element of the component and post fix the rules with “!important”. ID namespaces provide a higher priority over class, but can only be used in situations where there will never be more than one component in a document such as a global page header or footer. The namespace will prevent component CSS from bleeding out of the component’s boundaries especially when “!important” is also used.

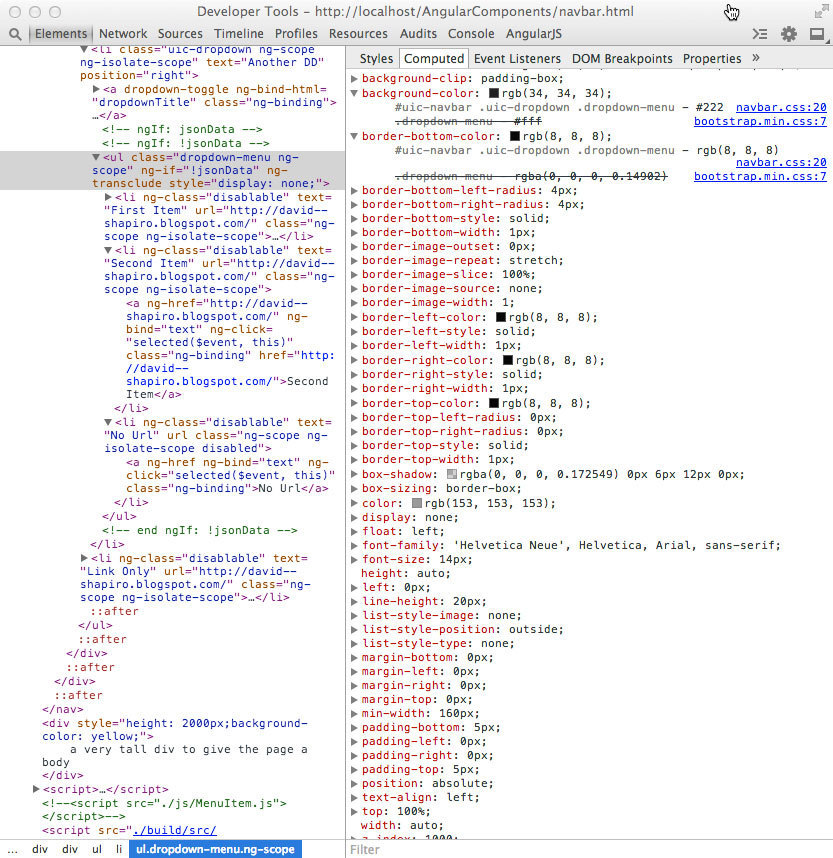

The final challenge in attempts to provide thorough style encapsulation is that of accounting for all the possible rules that can affect the presentation of any element in a component. If thoroughness is necessary, a good strategy is to inspect all the component elements with a browser’s web developer tools. Chrome, Safari, and Firefox allow you to see what all the computed styles are for an element whether the applied style rules are from a style sheet or are the browser default. Often the list can be quite long, but not all the rules necessarily affect what needs to be presented to the visitor.

Inspection of all the applied style rules with overrides expanded

Unit Testing Component Directives

Every front-end developer has opinions about unit testing, and the author of this book is no exception. One of the primary goals of the AngularJS team was to create a framework that allowed development style to be very unit test friendly. However, there is often a lax attitude toward unit testing in the world of client side development.

Validity and Reliability

At the risk of being flamed by those with heavy computer science or server application backgrounds, there are environments and situations where unit testing either doesn’t make sense or is a futile endeavor. These situations include prototyping and non-application code that either has a very short shelf life or has no possibility of being reused. Unfortunately this is an often occurrence in client side development. While unit testing for the sake of unit testing is a good discipline to have, unit tests themselves need to be both valid and reliable in order to be pragmatic from a business perspective. It’s easy for us propeller heads to lose site of that.

However, this is NOT the case with UI components that are created to be reused, shared and exhibit reliable behavior between versions. Unit tests that are aligned with a component’s API are a necessity. Fortunately, AngularJS was designed from the ground up to be very unit test friendly.

Traditionally, unit and integration test coverage for client-side code has been difficult to achieve. This is due, in part, to a lack of awareness of the differences between software design patterns for front and back end development. Server-side web development frameworks are quite a bit more mature, and MVC is the dominant pattern for separation of concerns. It is through the separation of concerns that we are able to isolate blocks of code for maintainability and unit test coverage. But traditional MVC does not translate well to container environments like browsers which have a DOM API that is hierarchical rather than one-to-one in nature.

In the DOM different things can be taking place at different levels, and the path of least resistance for client-side developers has been to write JavaScript code that is infested with hard references to DOM nodes and global variables. The simple process of creating a jQuery selector that binds an event to a DOM node is a basic example:

$('a#dom_node_id').onclick(function(eventObj){

aGlobalFunctionRef($('#a_dom_node_id'));

});

In this code block that is all too familiar, the JavaScript will fail if the global function or a node with a certain ID is nowhere to be found. In fact, this sort of code block fails so often, that the default jQuery response is to just fail silently if there is no match.

Referential Transparency

AngularJS handles DOM event binding and dependencies quite differently. Event binding has been moved to the DOM/HTML itself, and any dependencies are expected to be injected as function parameters. As mentioned earlier, this contributes to a much greater degree of referential or functional transparency which is a fancy way of saying that our code logic can be isolated for testing without having to recreate an entire DOM to get the test to pass.

<a ng-click="aScopedFunctionRef()"><a>

// inside an Angular controller function

ngAppModule.controller(function( $injectedDependencyFn ){

$scope.aScopedFunctionRef= $injectedDependencyFn;

});

Setting Up Test Coverage

In this section we will focus on unit test coverage for our component directive. As with much of this book, this section is not meant to be a general guide on setting up unit test environments or the various testing strategies. There are many good resources readily available starting with the AngularJS tutorial at http://docs.angularjs.org/tutorial. Also see:

http://karma-runner.github.io/

https://github.com/angular/protractor

https://code.google.com/p/selenium/wiki/WebDriverJs

For our purposes, we will take the path of least resistance in getting our unit test coverage started. Here are the prerequisite steps to follow:

- If not already available, install Node.js with node package manager (npm).

- With root privileges, install Karma: >npm install -g karma

- Make sure the Karma executable is available in the command path.

- Install the PhantomJS browser for headless testing (optional).

- Install these Karma add-ons:

npm install -g karma-jasmine --save-devnpm install -g karma-phantomjs-launcher --save-devnpm install -g karma-chrome-launcher --save-devnpm install -g karma-script-launcher --save-devnpm install -g karma-firefox-launcher --save-devnpm install -g karma-junit-reporter --save-dev - Initialize Karma

- Create a directory under the project root called /test

- Run >karma init componentUnit.conf.js

- Follow the instructions. It creates the Karma config file.

- Add the paths to all the necessary *.js files to the config file

- Create a directory called /unit under the /test directory

- In project/test/unit/ create a file called SmartButtonSpec.js

- Add the above path and files to componentUnit.conf.js

- Add the angular-mocks.js file to project/lib/

- Under /test create a launching script, test.sh, that does something like the following:

karma start karma.conf.js $* - Run the script. You will likely need to debug for:

- directory path references

- JavaScript file loading order in componentUnit.conf.js

When the karma errors are gone, and “Executed 0 of 0” appears, we are ready to begin creating our unit tests in the SmartButtonSpec.js file we just created. If the autoWatch option in our Karma config file is set to true, we can start the Karma runner once at the beginning of any development session and have the runner execute on any file change automatically.

The above is our minimalist set up list for unit testing. Reading the docs, and googling for terms like “AngularJS directive unit testing” will lead to a wealth of information on various options, approaches, and alternatives for unit test environments. Jasmine is described as behavioral testing since it’s command names are chosen to create “plain English” sounding test blocks which the AngularJS core team prefers since AngularJS, itself, is meant to be very declarative and expressive. But Mocha and QUnit are other popular unit test alternatives. Similarly, our environment is running the tests in a headless Webkit browser, but others may prefer running the tests against the real browsers in use: Chrome, Firefox, Safari, Internet Explorer, etc.

Component Directive Unit Test File

For every unit test file there are some commonalities to include that load and instantiate all of our test and component dependencies. Here is a nice unit test skeleton file with a single test.

5.8 A Skeleton Component Unit Test File

// SmartButtonSpec.js

describe('My SmartButton component directive', function () {

var $compile, $rootScope, $scope, $element, element;

// manually initialize our component library module

beforeEach(module('UIComponents'));

// make the necessary angular utility methods available

// to our tests

beforeEach(inject(function (_$compile_, _$rootScope_) {

$compile = _$compile_;

$rootScope = _$rootScope_;

$scope = $rootScope.$new();

}));

// create some HTML to simulate how a developer might include

// our smart button component in their page

var tpl = '<smart-button default-text="A Very Smart Button" '

+ 'active-text="Wait for 3 seconds..." '

+ 'debug="showAlert(\'a value on the $rootScope\')"'

+ '></smart-button>';

// manually compile and link our component directive

function compileDirective(directiveTpl) {

// use our default template if none provided

if (!directiveTpl) directiveTpl = tpl;

inject(function($compile) {

// manually compile the template and inject the scope in

$element = $compile(directiveTpl)($scope);

// manually update all of the bindings

$scope.$digest();

// make the html output available to our tests

element = $element.html();

});

// finalize the directive generation

}

// test our component initialization

describe('the compile process', function(){

beforeEach(function(){

compileDirective();

});

// this is an actual test

it('should create a smart button component', function(){

expect(element).toContain('A Very Smart Button');

});

});

// COMPONENT FUNCTIONALITY TESTS GO HERE

});

A Look Under the Hood of AngularJS

If you don’t have a good understanding of what happens under the hood of AngularJS and the directive lifecycle process, you will after creating the test boilerplate. Also, if you were wondering when many of the AngularJS service API methods are used, or even why they exist, now you know.

In order to set up the testing environment for component directives, the directive lifecycle process and dependency injection that is automatic in real AngularJS apps, must be handled manually. The entire process of setting up unit testing is a bit painful, but once it is done, we can easily adhere to the best-practice of test driven development (TDD) for our component libraries.

There are alternatives to the manual setup process described above. You can check out some of the links under the AngularJS section on the Karma website for AngularJS project generators:

https://github.com/yeoman/generator-karma

https://github.com/yeoman/generator-angular

There is also the AngularJS Seed GIT repository that you can clone:

https://github.com/angular/angular-seed

The links above will set up a preconfigured AngularJS application directory structure and scaffolding including starter configurations for unit and e2e testing. These can be helpful in understanding all the pieces that are needed for a proper test environment, but they are also focused on what someone else’s idea of an AngularJS application directory naming and structure should be. If building a component library, these directory structures may not be appropriate.

Unit Tests for our Component APIs

Unit testing AngularJS component directives can be a little tricky if our controller logic is in-lined with the directive definition object and we have created an isolate scope for the purposes of encapsulation. We need to set up our pre-test code a bit differently than if our controller was registered directly with an application level module. The most important difference to account for is that the scope object created by $rootScope.$new() is not the same scope object with the values and logic from our directive definition. It is the parent scope at the level of the pre-compiled, pre-linked directive element. Attempting to test any exposed functions on this object will result in a lot of “undefined” errors.

5.9 Full Unit Test Coverage for our Smart Button API

// SmartButtonSpec.js

describe('My SmartButton component directive', function () {

var $compile, $rootScope, $scope, $element, element;

// manually initialize our component library module

beforeEach(module('UIComponents'));

// make the necessary angular utility methods available

// to our tests

beforeEach(inject(function (_$compile_, _$rootScope_) {

$compile = _$compile_;

$rootScope = _$rootScope_;

// note that this is actually the PARENT scope of the directive

$scope = $rootScope.$new();

}));

// create some HTML to simulate how a developer might include

// our smart button component in their page that covers all of

// the API options

var tpl = '<smart-button default-text="A Very Smart Button" '

+ 'active-text="Wait for 5 seconds..." '

+ 'debug="showAlert(\'a value on the $rootScope\')"'

+ '>{{bttnText}} Text from transclusion.</smart-button>';

// manually compile and link our component directive

function compileDirective(directiveTpl) {

// use our default template if none provided

if (!directiveTpl) directiveTpl = tpl;

inject(function($compile) {

// manually compile the template and inject the scope in

$element = $compile(directiveTpl)($scope);

// manually update all of the bindings

$scope.$digest();

// make the html output available to our tests

element = $element.html();

});

}

// test our component APIs

describe('A smart button API', function(){

var scope;

beforeEach(function(){

compileDirective();

// get access to the actual controller instance

scope = $element.data('$scope').$$childHead;

spyOn($rootScope, '$broadcast').andCallThrough();

});

// API: default Text

it('should use the value of "default-text" as the displayed bttn text',

function(){

expect(element).toContain('A Very Smart Button');

});

// API: activeText

it('should display the value of "active-text" when clicked',

function(){

expect(scope.bttnText).toBe('A Very Smart Button');

scope.doSomething();

expect(scope.bttnText).toBe('Wait for 5 seconds...');

});

// API: transclusion content

it('should transclude the content of the element', function(){

expect(element).toContain('Text from transclusion.');

});

// API: debug

it('should have the injected logic available for execution', function(){

expect(scope.debug()).toBe('a value on the $rootScope');

});

// API: smart-button-click

it('should emit any events as APIs', function(){

spyOn(scope, '$emit');

scope.$emit('smart-button-click');

expect(scope.$emit).toHaveBeenCalledWith('smart-button-click');

});

// API: smart-button-command

it('should listen and handle any events as APIs', function(){

$rootScope.$broadcast('smart-button-command',

scope.$id, {setClass: 'btn-warning'});

expect(scope.bttnClass).toContain('btn-warning');

});

});

});

Code blocks in bold above are additions or changes to our unit test code skeleton. Note that the template used, covers all the API options. If this is not possible in a single template, than include as many as are need to approximate consumer usage of your component. Also note the extra step involved in accessing the controller and associated scope of the compiled and linked directive. If a template is used that produces more than one instance of the component, then referencing the scope via “$$childHead” will not be reliable.

Recall earlier in this chapter that software component APIs, on a conceptual level, are a contract between the developer and consumer. The developer guarantees to the consumer that the component can be configured to behave in a certain way regardless of the internal details. Comprehensive unit test coverage of each API is essential to back up the developer’s end of the agreement when the internals change via bug fixes and improvements. This is especially critical if the component library is commercial and expensive for the consumer, and where breakage due to API changes can result in legal action.

The above unit tests will server as the first line of defense in insuring that consistent API behavior is maintained during code changes. Only after a standard, published period of “deprecation” for any API should unit test coverage for it be removed.

Another beneficial side-effect of unit testing can be gained when considering the amount of time it takes to produce a unit test for a unit of functionality. If, on average, creating the test takes significantly longer than normal, then that can be a clue to questions the quality of the approach taken to provide the functionality. Are hard-coded or global dependencies being referenced? Are individual functions executing too much logic indicating they should be split up?

Summery

In this chapter, we’ve hopefully covered all the necessary aspects of developing a re-usable and portable UI component directive that is as high quality as possible given the current limitations of today’s major browsers. The “quality” referred to includes maximum encapsulation, documentation, test coverage, and API that facilitates easy consumption. Later in this book we will compare what we have built here to a version of the same component built using the looming W3C Web Components standards that will eventually obsolete the need for JavaScript frameworks in favor of native DOM and JavaScript methods for component Development.

In the next chapter, we will move up a level to what can be conceptually thought of as “UI container components”. These are DOM container component elements (tabs containers, accordions, menu bars, etc.) whose primary purpose is to be filled with and manage a set of UI components.