Chapter 7 - Build Automation & Continuous Integration for Component Libs

So you’ve succeeded in creating this fantastic set of UI components that encapsulate JavaScript, CSS, and HTML using AngularJS directives. Now what? They look and work great on our local development machine, but that is not the solution to our original business requirement. Our component library needs to be in current use by our target audience of web developers and designers, and there is a big gap between “looking good” on our development laptop and looking good in a production website or web application.

Delivering Components To Your Customers

We need to consider issues of performance, quality, delivery, and maintenance. Performance includes the obvious steps of minifying and concatenating our source files in the way that provides the best load and evaluation performance as possible for the end user. Quality includes the obvious steps of unit, integration, and end-to-end testing as part of any release to ensure that the APIs remain consistent. Delivery includes all the steps the customer must perform in order to find, access, download, and integrate our library components into their application including package management. Finally, we need to consider how to manage our ever-growing source code as we add new components to the library. Attempts to perform these steps by hand, for anything more than a single component, will quickly become a developer’s nightmare.

In the bad old days of software development, the typical (waterfall) release cycle took anywhere from 6 to 18 months from requirements to delivery. These periods would include, in sequence, UML modeling of the requirements, complete source code development, quality assurance processes, compiling, building, packaging and shipping. If requirements changed mid-cycle, often times this meant resetting the development cycle back to square one and starting over.

With the rise of the commercial Internet, delivery methods and timeframes began to change. Customers started downloading packages, updates, and documentation rather than waiting for them to arrive in the mail. So called “agile” methodologies attempted to shorten the development-delivery cycle from 3 weeks to 3 months. The era of formal scrum and extreme programming methods arose to whip lazy engineers into shape. As delivery cycles shortened, reasonable expectations were quickly replaced by the need for instant gratification.

Major software libraries and frameworks that now power the Internet have, at the absolute worst, a nightly build (24 hour delivery cycle). The norm is continuous integration and delivery. This typically means that as a developer commits a chunk of source code to the repository, an automated build and delivery process is triggered automatically. If that source code is flawed, but somehow manages to pass the full test suite, it still can wind up in the hands of the end user who performs another round of QA by default. Thus, most frameworks and libraries have older “stable branches” and newer “unstable branches”. The former is considered generally safe for production dependency, whereas, the latter is considered “use at your own risk” code.

In this chapter, we will look at a subset of the many tools that are used to automate the build and delivery process for JavaScript based libraries, and provide an example of one working continuous delivery system for our existing set of UI components. We will actually be automating two different build processes. One of them will be the development build process that takes place on our local development laptops. The other one will be the build process that takes place in the “cloud” when any development team member commits code into the main repository branch.

Source Code Maintenance?

Source code maintenance refers to all of the technics and best practices that enable the product or package to be easily added to, or upgraded by, developers. In previous chapters, we’ve already covered many of these technics for the JavaScript source code ad nauseam including dependency injection, encapsulation, declarative programming, liberal source documentation, DRY, and comprehensive unit test coverage. These technics can be categorized as relating to the individual developer.

Many enterprise organizations skip these some or all of these practices in the interest of delivering a product a few days or weeks earlier. This is the recipe for an eventual massive lump of jQuery spaghetti that periodically must be dumped in the trash and development restarted from scratch. In my many years in Silicon Valley, I have yet to see any major technology organization conduct their development otherwise. The sources of this are typically non-technical marketing bozos in executive management who make hubris driven technical decisions for the engineering organization.

Almost as destructive to good source code maintenance are the outdated ivory tower architects and engineering managers of “proprietary software” who still think JavaScript is not a real programming language. They tend to build the engineering environments around increasingly arcane and inappropriate tools like Java, Oracle, and CVS/SVN. In their quest to abstract away JavaScript in a manner that emulates the traditional object-oriented environments, they gravitate toward tools like GWT and ultimately the same massive, unmaintainable JavaScript hairball.

Git and GitHub

Before I digress too far, lets back up and talk about source code maintenance in multi-developer environments. Until now, the maintenance technics discussed have been restricted to those under the control of a single developer. There is no debate that concurrent versioning management is a necessity. The versioning tools chosen need to facilitate, not hinder, rapid, iterative development by a team of developers. The tool of choice in the AngularJS world is Git. The Git server of choice is GitHub. The source code for this book is located in a public repository on GitHub. An in depth discussion about Git and how to best use it is beyond the scope of this book, and moving forward, a normal user level knowledge of Git will be assumed.

The open-source ecosystem on GitHub has benefits beyond facilitating geographically distributed development teams. Public repositories on GitHub can take advantage of things such as package and plugin registration systems including Bower, NPM, Grunt, and many more. If you produce a package, framework, or library that is useful to others in front-end development, as we are trying to do in this book, with a simple JSON config file, the library can be registered on Bower for others to easily locate and install including all dependencies. Projects hosted on GitHub can also take advantage of continuous integration services such as Travis-CI, auto dependency version checking and more.

Git is rapidly replacing Subversion and other proprietary repository management systems because it emphasizes frequent creation and destruction of feature branches, commit tagging, forking, and pull requests. SVN emphasizes “main branch” development and is better suited of longer cycle releases. Git is better suited for rapid, distributed development while preventing junior developers from committing destructive code to the main branch. In many high profile open source projects anyone can check out or fork the repository, fix a bug or make an improvement, and issue a “pull request”. If the committed code is deemed of value by the core team of committers, the code is then “pulled” into the main repository. If a developer makes enough positive contributions to the project, they can often earn their way onto the core team.

Tooling

In front-end development, new tools arise every month. We will focus on those that are most popular and useful and include discussion on those that are gaining in popularity and likely to replace certain tools already entrenched. The list includes:

- Server-side package management - Node and NPM

- Task runners for automation - Grunt and Gulp plus common tasks for:

- JavaScript code linting

- HTML to JavaScript file includes

- CSS builds from LESS or SASS source

- JavaScript and CSS concatenation

- JavaScript and CSS minification

- Test runners

- File watchers

- Client-side package management - Bower

- Continuous Integration in the Cloud - Travis-CI

UI Library Focused

Our goal will be to discuss how these tools can facilitate build and delivery of a component library similar to jQuery UI or Bootstrap. The vast majority of scaffolds, and project starters for AngularJS and other JavaScript framework projects are geared heavily towards single page applications. However, available scaffolds and starters for component libraries are almost non-existent.

One of the unique needs in this area is the ability for the user to download a build that includes just a subset of the library or even an individual component rather than the whole thing. It is rare when a web application or website will need to use every component of a library. Having just the necessary subset with required dependencies can significantly improve loading performance.

Our goal will not be to present comprehensive coverage of the above tools, preferring instead to cover the general concepts given that the tools themselves come and go, and there are many ways to implement them for any given situation. Any provided CLI commands assume Mac or Linux as the OS platform. The project used for inspiration in this chapter is Angular-UI Bootstrap https://github.com/angular-ui/bootstrap.

Project Directory Structure

Before we start our tour through the laundry list of the popular open source tools for maintaining a UI component library, we need to take a quick detour and consider a directory structure that facilitates optimum organization of the source code.

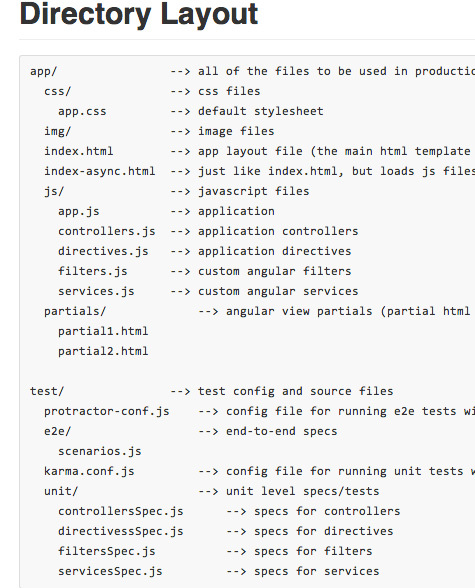

In our previous examples, as we began initial UI component development, we used a very flat structure that grouped files by either type or purpose. If you recall the Karma configuration file from Chapters 5 and 6, we were including all of the JavaScript files in one directory and all of the unit test files in another. Grouping files by type and purpose is best suited for a single page application directory structure. If you look at the directory structure for the Angular-seed application, you will notice this type of organization:

https://github.com/angular/angular-seed#directory-layout

Screen grab of the AngularJS’ team’s recommended directory structure for an AngularJS app.

Up until now, we’ve only developed JavaScript source, HTML templates, CSS, and unit tests for a total of four UI components. However, in a realistic situation, this sort of library could have a couple dozen or more components. This sort of structure can become difficult to work with in situations where we need to hunt for and open all of the files for a single component in an IDE. In fact, just knowing which files belong to a particular component can cause a headache.

An alternative approach for organizing a library of components would be to group all of the files related to a particular component by directory named for the component. For example, we could create a directory like the following for the source files of each component:

SourcefileorganizationintheNavbardirectoryforallfilesassociatedwiththeNavbarcomponent

ProjectRoot/

Navbar/

Navbar.js

Navbar.tpl.html

Navbar.less

test/

NavbarSpec.js

docs/

Navbar.demo.html

Navbar.demo.js

This way it becomes obvious to anyone new to the project which files are associated with which component. Additionally, when it comes time to automate the build workflow in a way that we can optionally build just one or two components instead of the entire library, we can better ensure that only the source files under the “Navbar” directory are used when “Navbar” is an argument to the build command.

When you consider that a highly encapsulated UI component that includes its own JavaScript behavior, CSS styling, and HTML templating, is a mini application conceptually, maintaining source files in a directory per component seems logical. This is not to say that every AngularJS component library project should necessarily be structured this way. Chosen structure should reflect a project’s needs, goals, and development roadmaps. Some UI component libraries will be coupled with a large application, and others may be mixed in with non-UI components. There are a couple suggestions for help in matching a directory structure with requirements that can be offered. First, consider how quickly an engineer new to the project can figure out what can be found where, and second, check out all the great project starter templates contributed by the AngularJS community at Yeoman:

For the remainder of this chapter we will be organizing the source code by directory for each component which will be reflected in the build workflow configuration files.

Node.js and NPM

Node.js is a server side container and interpreter for running JavaScript analogous to how the browser is the container on the client-side. In fact, Node.js is based on the same JavaScript engine as Chrome and is therefore actually coded primarily in C++ rather than JavaScript as many people assume. What makes Node.js different from most server-side language interpreters or runtime environments is it is designed to execute multiple commands asynchronously (non-blocking) via a single OS thread rather than synchronously (blocking). In this way, idle time for any thread of execution is minimized and computer CPU is used in a much more efficient manner. A Node.js webserver will handle multiple requests per process; whereas, other webservers will typically dedicate an entire process to handling one request.

Also, contrary to popular assumption is that Node.js was not created by front-end developers who wanted to use JavaScript to program on servers, but rather was picked as the console interface language for Node.js because it was the language in widest use that offered asynchronous and functional programming syntax. If such syntax were offered by Ruby, PHP, Python, PERL, or Java, then one of those languages might have been used instead.

Another advantage of Node.js for front-end developers is that it (along with NoSQL databases) allows one to perform full-stack development in one language. This is significant since it is highly likely that at some point (Web 4.0?), the network and all of the AJAX or REST boilerplate will be abstracted away via platforms like Meteor.js in much the same manner that AngularJS abstracts away the need for any manual data and event binding today. If you are relatively new to web development and plan to be in this business for the next several years, then it is highly advisable to spend professional development time learning Node.js rather than Ruby, PHP or Python even though more mature server-side MVC frameworks exist for them.

The default libraries included with Node.js allow easy access and manipulation of all I/O subsystems on the OS for *nix based machines. This includes file and network I/O such as setting up, managing, and tearing down HTTP webservers, or reading and writing files to disc.

That said, make sure Node.js, the most recent major release number (with stable minor version number), is installed globally on your development machine http://nodejs.org/. OS X should already have it, and most Linux’s should have easy access via a package manager. My condolences to those behind corporate firewalls with draconian port policies. It may be a bit more difficult obtaining the latest necessary packages.

Mac users without Node.js should install the latest Xcode from the app store, and then install a Ruby package manager called Homebrew. From there, you run:

~$ sudo brew install git

~$ sudo brew install node

Finally make sure NPM (Node Package Manager) is updated to the latest.

~$ sudo npm update -g

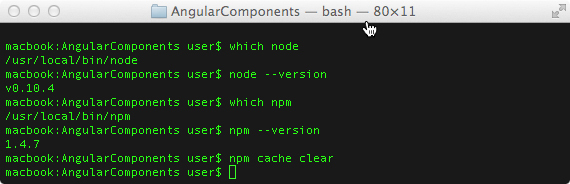

You should be able to run user$ which npm and see it in your path.

Commands to check for Node and NPM on Mac and Linux plus cache clearing

Having the up-to-date version of NPM and clearing NPM’s cache will improve the chances of successful downloads of the necessary NPM modules including Grunt, Karma, Bower, and Gulp.

Within any given project directory that utilizes NPM modules, there should be a package.json file in the root that holds references to all of the projects NPM dependency modules at or above a particular version. There will also be a sub directory called node_modules/ where all the local project dependencies are stored. This directory name should be included in all configuration files where directories and files are excluded from any processing such as .gitignore. We do not want to package or upload the megabytes of code that can end up in this directory, nor do we want to traverse it with any task commands that search for JavaScript files with globs such as /*.js as this can take some time and eat up a lot of CPU needlessly.

By listing all the NPM module dependencies in package.json, the project becomes portable by allowing the destination user to simply run ~$ npm install in the project root directory in order to get all of the required dependencies. All necessary documentation plus available modules can be found at the NPM website:

We will defer listing our package.json file example until towards the end of this chapter, as its contents will make a lot more sense after we have covered all the third party packages that it references.

Task Runners and Workflow Automation

Build automation has been a vital part of software development for decades. Make was the first such tool used in Unix / C environments to simplify stringing together several shell commands required to create tmp directories, find dependencies, run compilation and linking, copy to a distribution directory, and clean temporary files and directories created during the process.

Ant was the next tool that arose along with Java in the 90s. Rather than programmatic statements, Ant offered XML style configuration statements meant to simplify creating the build file. A few years after Ant came Maven, which offered the ability to download build files and dependencies from the Internet during the build process. Maven was also XML based and Java focused. Maven inspired several more build automation runners specific to languages such as Rake for Ruby and Phing for PHP.

In the JavaScript world, Grunt is the task automation tool that is currently dominant. There are thousands of available tasks, packaged as NPM modules on the web, which can be configured and invoked in a project’s Gruntfile.js. There is another task runner called Gulp that is aiming to knock Grunt off of its throne. It will likely succeed for some good reasons.

Because at the time of this writing, Gulp and the available Gulp tasks are not yet numerous and mature enough to satisfy our build automation needs at a production level of quality, we will explore build automation for our UI component libraries using both tools.

Grunt - The JavaScript Task Runner

Grunt is acquired as an NPM module. It should be installed globally in your development environment:

~$ sudo npm install -g grunt-cli

It should be available in your command path after installation. If it is not, it may be necessary to locate the installed executable and symlink it to a name in your command path. Documentation can be found on the Grunt project website:

Registered Grunt tasks can be searched at:

When the grunt command is run in the root directory of a project, it looks for a Node.js file called Gruntfile.js which contains its instructions. There are some templates available on the Grunt project website that can be used with the command grunt-init to generate a Gruntfile based on answers to various questions, however, it is probably faster, easier and more informative to locate GitHub repos of similar projects and inspect the contents of their Gruntfiles.

Gruntfiles are Node.js JavaScript files. In them, there are typically three primary commands or sections:

grunt.loadNpmTasks( 'task-name' );

grunt.initConfig({configurationObject});

grunt.registerTask('task-name', ['stepOne', 'stepTwo', 'stepThree', ... ]);

Third party tasks are loaded. A (sometimes very large) JSON object is used to reference and configure the loaded tasks, and then one or more task names are defined with an array of steps that map to the definitions in the configuration object. These task names can then be used in a file watcher or on the command line:

project_dir$ grunt task-name

7.0 Example Gruntfile.js with a Single Task

module.exports = function (grunt) {

// load 3rd party tasks

grunt.loadNpmTasks('grunt-contrib-uglify');

// configure the tasks

grunt.initConfig({

// external library versions

ngversion: '1.2.16',

bsversion: '3.1.1',

// make the NPM configs available as vars

pkg: grunt.file.readJSON('package.json'),

// provide options and subtasks for uglify

uglify: {

options: {

banner: '/*! <%= pkg.name %> */\n',

mangle: false,

sourceMap: true

},

build: {

src: 'js/MenuItem.js',

dest: 'build/MenuItem.min.js'

},

test: {

files: [{

expand: true,

cwd: 'build/src',

src: '*.js',

dest: 'build/test',

ext: '.min.js'

}]

}

}

});

// define our task names with steps here

grunt.registerTask('default', ['uglify:test']);

};

The code listing above contains an example of a Gruntfile.js with a single task “default” which will run on the command line simply with the grunt command and no extra arguments. It runs a configured subtask of “uglify” which is a commonly used JavaScript minifying tool.

In practice, a Gruntfile with a single task would be pointless since the whole point of build automation is to perform several tasks. The point of the above listing is to illustrate the three main sections of the Gruntfile and what typically goes in them. The first step in debugging a Gruntfile that fails is to check each of these three sections and make sure all the names jibe.

7.1 Example Gruntfile.js with a Multiple Tasks

module.exports = function (grunt) {

// load 3rd party tasks

grunt.loadNpmTasks('grunt-contrib-watch');

grunt.loadNpmTasks('grunt-contrib-concat');

grunt.loadNpmTasks('grunt-contrib-copy');

grunt.loadNpmTasks('grunt-contrib-jshint');

grunt.loadNpmTasks('grunt-contrib-uglify');

grunt.loadNpmTasks('grunt-html2js');

grunt.loadNpmTasks('grunt-import');

grunt.loadNpmTasks('grunt-karma');

grunt.loadNpmTasks('grunt-conventional-changelog');

grunt.loadNpmTasks('grunt-ngdocs');

grunt.loadNpmTasks('grunt-contrib-less');

// configure the tasks

grunt.initConfig({

// external library versions

ngversion: '1.2.16',

bsversion: '3.1.1',

// make the NPM configs available as vars

pkg: grunt.file.readJSON('package.json'),

// provide options and subtasks for uglify

uglify: {

options: {

banner: '/*! <%= pkg.name %> */\n',

mangle: false,

sourceMap: true

},

build: {

src: 'js/MenuItem.js',

dest: 'build/MenuItem.min.js'

},

test: {

files: [{

expand: true,

cwd: 'build/src',

src: '*.js',

dest: 'build/test',

ext: '.min.js'

}]

}

},

html2js: {

options: {},

dist: {

options: {

// no bundle module for all the html2js templates

module: null,

base: '.'

},

files: [{

expand: true,

src: ['template//*.html'],

ext: '.html.js'

}]

},

main: {

options: {

quoteChar: '\'',

module: null

},

files: {

'build/tmp/Dropdown.tpl.js': ['html/Dropdown.tpl.html'],

'build/tmp/MenuItem.tpl.js': ['html/MenuItem.tpl.html'],

'build/tmp/Navbar.tpl.js': ['html/Navbar.tpl.html'],

'build/tmp/SmartButton.tpl.js': ['html/SmartButton.tpl.html']

}

}

},

watch: {

files: [

'js/*.js'

],

tasks: ['uglify']

},

import: {

options: {},

dist: {

expand: true,

cwd: 'js/',

src: '*.js',

dest: 'build/src/',

ext: '.js'

}

},

less: {

dev: {

files: {

'css/ui-components.css': 'less/ui-components.less'

}

},

production: {

options: {

cleancss: true

},

files: {

'css/ui-components.css': 'less/ui-components.less'

}

}

}

});

grunt.registerTask('css', ['less:production']);

grunt.registerTask('default', ['html2js']);

grunt.registerTask('test', ['html2js:main', 'import:dist', 'uglify:test']);

};

The code listing above is closer to a real world Gruntfile with multiple 3rd party task imports, a much longer configuration object, and multiple registered task names with steps at the end. The task names in bold should be recognizable as typical steps performed somewhere in the build workflow including testing, concatenating, minifying, linting, etc.

The last line in the listing shows three task steps in sequence. The first two steps each write out files to disc before beginning the next step. For small projects, the time this takes will not be noticeable. However, for large libraries or applications with hundreds to thousands of source files, the disc I/O time can take minutes, which becomes impractical to run whenever a single source file is saved.

This is one of the major complaints of those who have created Gulp as an alternative. Rather than outputting directly to disc, the default output of any Gulp task is a data stream that can be “piped” directly to the next task instead. The output data from a task or series of tasks will only be written to disc when explicitly commanded. In addition, tasks can be executed concurrently or in parallel if one is not dependent on the previous. Complete, in memory processing for very large projects can result in time savings of several orders of magnitude. We will further discuss the differences, pros, and cons of both Grunt and Gulp in later sections.

Useful Tasks for a Component Lib Workflow

The build tasks we may want to automate as part of our workflow typically fall into a few different categories.

Tasks in Sequence

We likely want to perform some preprocessing of our source files to inline the templates and generate associated CSS. Then we would want to check the quality of these files, and generate any associated documentation. Finally, we want to create performance-optimized versions of these files suitable for distribution to our customers. Optionally, we might want to create a second layer of automation by setting up file watchers to perform certain tasks when the files are saved. For example, we would want any CSS output immediately when we save a .less file, and we would want to run unit tests and source linting before deciding to make a Git commit of our recent batch of changes.

Tasks Before and After Committing

Looking at this from another angle (pun intended), when we add or modify a component, we want to run some tasks (unit tests and linting), then determine whether or not to commit our code to the main repository based on the outcome. If our code quality is up to par, then we want to proceed with the tasks in the workflow that move the component code toward production including minification, documentation, integration testing and so on.

Preprocessing Source Files with LESS, html2js and JavaScript Imports

Excluding unit tests and configuration files, most UI developers find it easiest to edit HTML, CSS and JavaScript as separate files. This includes all of the preprocessor languages such as CoffeeScript, TypeScript, and Dart for JavaScript, Jade, HAML, and Slim for HTML, and LESS or SASS for CSS.

Source code preprocessors, in some cases, solve some serious limitations inherent in the language they compile to. Others are nothing more than syntactic sugar for developers who feel comfortable working with syntax similar to their server-side language. For our purposes, we will remain preprocessor agnostic with the exception of CSS.

CSS preprocessor languages add a tremendous amount of value beyond what CSS has to offer. CSS has no notion of variables, functions, or nested rule sets. Because of this CSS for large projects can end up with a lot of duplicated rules and ultimately poor network loading performance and very difficult maintenance. The manner in which they can increase styling consistency and reduce code duplication is beyond the scope of our topic. However, one nice thing about LESS and SASS is that plain old CSS syntax is perfectly valid, so there is no reason for us not to include one as part of our example build workflow which will include CSS source code in LESS files.

If you navigate to plugins page of the Grunt project website and search for “less” a list of many modules appear. The one at the top “grunt-contrib-less” is what we want, as it has the code that compiles LESS to CSS. From the root directory of our project, we download this module with the following command:

npm install grunt-contrib-less --save-dev

and then add the following line to our Gruntfile.js:

grunt.loadNpmTasks('grunt-contrib-less');

The NPM command installs the plugin local to the project under the node_modules/ directory. The –save-dev option will add a dependency reference to the project’s package.json file. In this way, the project can be portable without having to include anything under the node_modules/ directory in the tar ball or Git glob, which can be thousands of files. All one needs at the destination is the package.json file in the project root, and then they can run npm install to get all the dependency modules downloaded to the node_modules/ directory.

Next, we would add something like the following to our Gruntfile.js in order to provide the LESS and Grunt with a useful configuration:

7.2 Adding a LESS task to a Gruntfile.js

grunt.initConfig({

less: {

dev: {

files: [

{

expand: true, // Enable dynamic expansion.

cwd: 'src/', // Src matches are relative to this path.

src: ['/*.less'], // Actual pattern(s) to match.

dest: 'build/src/', // Destination path prefix.

ext: '.css' // Dest filepaths will have this extension.

}

],

},

production: { ... }

});

The files object contains information that will search for all .less files under the src/ and any sub directories as source to compile, and the output will be placed in build/src/. The dev:{} object defines one subtask for the “less” task that we can call from the command line as:

~$ grunt less:dev

It is typical to have more than one subtask configuration for different purposes such as development vs. production or distribution. The dev task outputs individual .css files for development purposes, whereas, a production subtask might use a different source .less file that has @includes for several LESS modules to build the entire project CSS.

Besides the actual LESS compiling, the above configuration example can be generalized to most other Grunt task configurations for file input and output.

As mentioned previously, it is preferable to maintain separate source files for HTML templates and JavaScript for ease of development, spotting bugs, and cooperation from our IDE’s. However, because tight integration and a high level of encapsulation is desired for our components, we want to inline the HTML template as JavaScript into the same file as the primary directive definition object for our custom HTML element that encloses the component in the DOM.

This is a bit different from the way templates are handled in libraries like (Angular) UI Bootstrap, and AngularStrap. Those libraries are intended to be forked, extended and modified to the user’s liking, so the HTML templates are compiled and (optionally) included as JavaScript in separate AngularJS modules along side the component modules that contain the JavaScript for the directives and services. The need to swap templates is a common occurrence. Because our strategy is focused on creating UI components meant to enforce styling for consumption by junior developers and designers in large organizations, we need to treat JavaScript and the associated HTML as one. If browser technology allowed the same for CSS, we would include that as well.

What this means is that we will need a task(s) that will stringify the HTML in the template, add it as the value to a var definition so it becomes legal JavaScript, and then insert is as a “JavaScript include” into the file with the directive definition. JavaScript, unlike most other languages, still does not have the notion of “includes”. The hope is that it will be an added feature for ES7, but for today, we need some outside help.

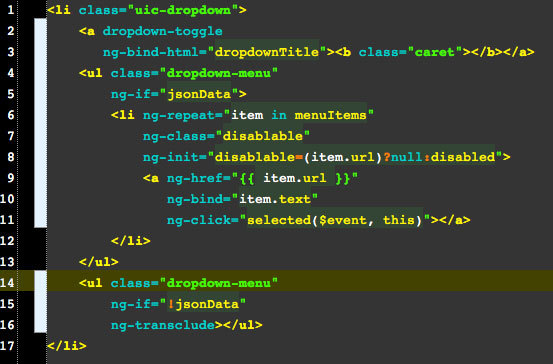

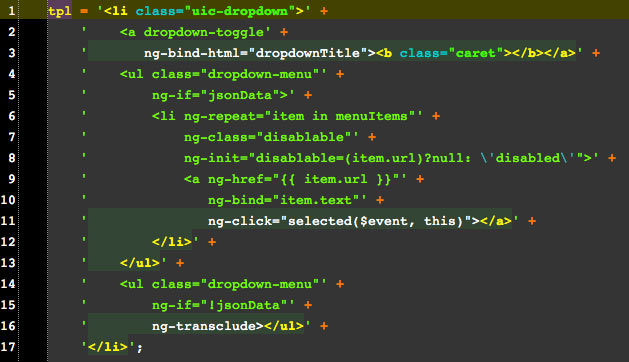

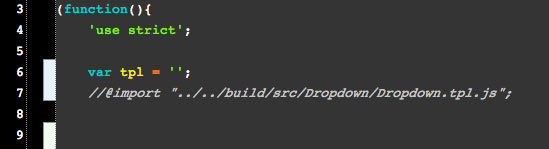

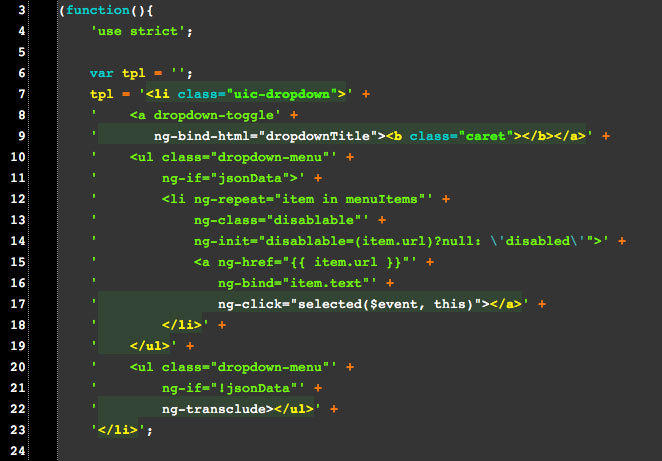

The following series of screen grabs illustrate how the source files that we would edit in our IDE need to be transformed into a consolidated file that we would test in our browser and with unit coverage.

Dropdown.html source file template that is edited as HTML

Generated Dropdown.tpl.js after conversion to valid JavaScript by a Grunt task

The editable source file, Dropdown,js with a special “//@import” comment

Generated Dropdown.js after the Grunt task replaces the “import” statement with the template JavaScript

By maintaining editable versions of the html template and JavaScript without the in-lined template, and as both valid HTML and JavaScript, we are free to develop these files without any nasty clutter or screams from our IDE about invalid code syntax.

However, this can create the undesirable situation where we are not able to perform the fast loop of “edit-and-reload”, the instant gratification that front-end developers love. We get around this obstacle by setting up a “file watcher” as another Grunt task that will monitor file changes in the source directories, and run the conversion tasks automatically. We can even go so far as to enable a “live-reload” as a Grunt task so we do not need to constantly hit the browser “reload” button in order to see the fruits of our work upon each edit.

First let’s cover getting the source file processing and merging configured in Grunt. At the time of this writing, no Grunt plugins did exactly what we needed as shown above. However, some came very close. “grunt-html2js” will stringify an HTML file into an AngularJS module meant to be loaded into $templateCache at runtime, and “grunt-import” will insert the contents of one JavaScript file into another, replacing an “@include filename.js” statement. The issue with the latter is that having “@include filename.js” sitting in a JavaScript source file is not valid JavaScript and results in serious complaints from most IDEs. We would need to tweak the task so that the import statement can sit behind a JavaScript line comment as //@import filename.js which would be replaced with the template JavaScript.

Tweaking these plugins to do what we need involves a couple alterations to the Node.js source code for the tasks located under:

project_root/node_modules/[module_name]/tasks/

It is best not to alter these tasks in place unless you fork the module code, make the changes, and register as new node modules, otherwise Node.js dependency management for the project will break. A short term solution would be to copy the module directory to a location outside of node_modules/, make the edits, and import them into the grunt configuration using grunt.loadTasks(‘task_path_name’). Since Node.js development is beyond the scope of this book, please see the book’s GitHub repo for the actual code alterations. We will add a bit of description to these tasks and reference them as html2jsVar and importJs.

Let’s look at the Grunt configuration that watches all of our source file types where they live, and runs the development tasks upon any change:

7.3 Grunt Source Code Development Tasks

// prepare encapsulated source files

grunt.loadNpmTasks('grunt-contrib-less');

grunt.loadTasks('lib/project/grunt-html2js-var/tasks');

grunt.loadTasks('lib/project/grunt-import-js/tasks');

// configure the tasks

grunt.initConfig({

...

html2jsVar: {

main: {

options: {

quoteChar: '\'',

module: null

},

files: [{

expand: true, // Enable dynamic expansion.

cwd: 'src/', // Src matches are relative to this path.

src: ['/*.html'], // Actual pattern(s) to match.

dest: 'build/src/', // Destination path prefix.

ext: '.tpl.js' // Dest filepaths will have this extension.

}]

}

},

importJs: {

dev: {

expand: true,

cwd: 'src/',

src: ['/*.js', '!/test/*.js'],

dest: 'build/src/',

ext: '.js'

}

},

less: {

dev: {

files: [

{

expand: true, // Enable dynamic expansion.

cwd: 'src/', // Src matches are relative to this path.

src: ['/*.less'], // Actual pattern(s) to match.

dest: 'build/src/', // Destination path prefix.

ext: '.css' // Dest filepaths will have this extension.

}

],

}

},

watch: {

source: {

files: ['src//*.js','src//*.html','!src//test/*.js'],

tasks: ['dev'],

options: {

livereload: true

},

},

},

});

grunt.registerTask('dev', ['html2jsVar:main', 'importJs:dev', 'less:dev']);

The code listing above contains the contents of our Gruntfile.js (in bold) that we have added. We can now run:

~$ grunt watch:source

…from the command line. As long as we point our test HTML page to the correct JavaScript and CSS files under the project_root/build/src/ directory, we can edit our uncluttered source files, and immediately reload the merged result to visually test in a browser. Running the above command even starts a LiveReload server. If we enable the test browser to connect to the live-reload port, we don’t even need to hit “refresh” to see the result of our source edit.

Notice in two of the “files” arrays we include ‘!/test/*.js’. This addition prevents any watches or action on the unit test JavaScript files. As the UI component library source code grows, we need to limit the source files operated on in order to maintain the ability to perform instant reloads. The processing time in milliseconds is sent to stdout, so we can keep tabs on how long the cycle takes as components are added. If the library size becomes large enough, it may be necessary to further restrict the file sets in the Grunt config, or to switch to a streaming system like Gulp. Also, note that if for some reason we do not wish to start a “watch”, we can call grunt dev at the command line to run source merging once after an edit.

Source Code Quality Check with jsHint and Karma

Now that we have the portion of our build workflow configured for ongoing source file editing, it is time to think about the next step in the build workflow process. Assume we have modified or added a feature or component, which has involved edits to several source files. Everything looks good in our test browser, and we are thinking about committing the changes to the main repository branch. What can we do to automate some quality checks into our pre-commit workflow?

The first and most obvious task is running the unit tests that we have been writing as we have been developing the component. You have been doing TDD haven’t you? Conveniently, there is a Karma plugin for Grunt that can be installed. It does exactly the same thing as using Karma directly from the command line as we have discussed in previous chapters.

In previous chapters we had Karma configured to run using Chrome, and to watch the source files directly in order to re-run upon any change. When running Karma from Grunt, it usually preferable to use a headless browser (PhantomJS) and let Grunt handle any file watches. The Karma Grunt task allows you to you to use different Karma configuration files, or to use one file and override certain options. Maintaining multiple Karma config files would likely become more painful than just overriding a few options, which is how we will handle these to changes in our Gruntfile.js. One rather irritating discovery about running Karma from Grunt is that all of the Karma plugins referenced must also be installed locally to the project, rather than globally which is common for developers working on many projects*.

Another common quality check is code “linting”. The most popular linter for JavaScript at the time of this writing is jsHint. jsHint is somewhat of an acrimonious fork of jsLint, as many in the JavaScript community felt the latter was becoming more opinionated than practical*.

jsHint can be configured to check for all kinds of syntax and style issues with JavaScript source code. There are two main areas of focus when code linting. The first is concerned with error prevention. JavaScript was originally design to be very forgiving of minor mistakes in order that non-engineers could tinker with it while creating web pages. Unfortunately, a uniform feeling of syntax forgiveness is not shared among all browsers. Trailing commas do not cause errors in Firefox or Chrome, whereas they do in Internet Explorer. JavaScript also has syntax rules that do not cause errors in any browser, but have a high probability of leading to errors in the future. Optional semi-colons and braces are the two worst offenders. jsHint can be configured to watch and report many code issues that degrade quality and maintenance like these.

The other area where a tool like jsHint is handy is in multi-developer environments. A major best practice for multi-developer teams is a consistent coding style. A good lead developer will enforce a code style guide for the team, and adhering to a coding style for almost all open source project contributions is a requirement. Without a consistent coding style, engineers will always do there own thing, and it will become increasingly difficult for one engineer to understand and maintain another engineer’s source code. jsHint can be of assistance in this area, at least as far as code syntax is concerned.

Creating a custom configuration for a project’s jsHint involves adding a file to the root directory of a project with various “switches” turned on. Below is the .jshintrc file in use for this project at the time of this writing.

7.4 jsHint Configuration JSON - .jshintrc

{

"curly": true,

"immed": true,

"newcap": true,

"noarg": true,

"sub": true,

"boss": true,

"eqnull": true,

"quotmark": "single",

"trailing": true,

"strict":true,

"eqeqeq":true,

"camelcase":true,

"globals": {

"angular": true,

"jquery":true,

"phantom":true,

"node":true,

"browser":true

}

}

Some of switches above may be obvious. Since the topic for this book is not general JavaScript syntax or maintenance, please visit the jsHint project webpage for comprehensive documentation.

Configuration switches can also be specified directly in your Gruntfile.js in the options:{} object. Additionally, you may want to create jsHint subtasks that run it after merging or concatenating JavaScript source files, and there are optional output report formatters that your may prefer. By default, the jsHint grunt task will fail and abort any grunt process on errors unless you set the “force” option to “true”.

An up and coming alternative to jsHint at the time of this writing is ESLint, created by Nicholas Zakas in mid-2013. ESLint includes all of the switches and rules of jsHint, plus a lot more rules organized by purpose. What sets ESLint apart from jsHint (or jsLint) is that ESLint is extensible. jsHint comes with a preset list of linting switches. Additional options or switches must be built into the source code. ESLint, on the other hand, allows you the ability to add additional rules via configuration JSON. More info can be gleaned at: http://eslint.org/

Putting all of the above together in our Gruntfile.js, we get:

7.5 Grunt Pre-Commit Code Quality Tasks

// check the js source code quality

grunt.loadNpmTasks('grunt-contrib-jshint');

grunt.loadNpmTasks('grunt-karma');

// configure the tasks

grunt.initConfig({

...

karma: {

options: {

configFile: 'test/karma.conf.js',

autoWatch: false,

browsers: ['PhantomJS']

},

unit: {

singleRun: true,

reporters: 'dots'

}

},

jshint: {

options: {

force: true // do not halt on errors

},

all: ['Gruntfile.js', 'src//*.js']

}

});

grunt.registerTask('preCommit', ['jshint:all', 'karma:unit']);

The additions to our Grunt configuration file above will help to ensure code quality and style conformance prior to making a commit to a team repository, however it is not a substitute for developer testing in all the major browsers or peer code reviews. It’s the minimum that a developer can do to avoid team embarrassment when their commit breaks other parts of the code base.

Before moving on to other essential build workflow automation tasks, it’s worth mentioning that until now our tasks have included all source files as input. As component libraries grow and tasks begin to eat up more time and CPU, Grunt gives us the ability to pass in arguments in addition to tasks to run on the command line. If it makes sense, we can pass in the names of individual components for processing, rather than everything at once. By using Grunt variables, templates, and a bit more coding, we can run tasks on just the desired modules and their direct dependencies. This is part of the reason for restructuring the source code directory organization as we did. By calling Grunt with something like the following on the command line we can pass in a component “key=value” (prefixed with a double dash) that can be used within the Gruntfile.js to only select and operate on files and directories of that name:

~$ grunt preCommit --component=Dropdown

We can then access this in the Gruntfile like this:

var component = grunt.config('component');

If, on the other hand, will do not need the parameter to be globally accessible in our Gruntfile.js, and we just want to pass parameters or arguments into a particular task, we do so with colon notation on the command line:

~$ grunt build:navbar

~$ grunt build:dropdown:menuItem

Assuming the colon separated strings are not subtasks of build, they can be accessed locally inside the build task function as this.args.

In the next section, we will create an example section of our Gruntfile.js that uses task arguments to create custom builds that include just a subset of the available UI components.

Performance Optimization with Concat and Uglify

Until now we have explored task automation related to source code development. Let’s assume we’ve developed a new UI component, and we are ready to either commit or merge it into our main Git branch. As is standard these days in web tier development, we should run a build on our local development laptop upon each commit to make sure the build succeeds before pushing our commit to the origin repository server.

If you have a good devOps engineer on the team, she has created for you a development VM (virtual machine) with an environment that is as identical to the production server as possible, using tools like Vagrant. Your build should perform the same steps as closely as possible to those on the team integration server. There will still be differences, such as running time consuming multi-browser e2e, and regression tests.

Regardless, the build should produce production ready files of our component library including necessary dependencies. “Production ready” is defined, at a bare minimum, to be minified JavaScript that is concatenated into as few files as possible to minimize download file size and latency. It can be defined, more robustly, to include all API documentation and demos, version information, change logs, additional unminified files with source maps, etc.

One special requirement, as mentioned earlier, is the ability to create a build that includes just the modules or components that a particular customer may need, so they do not have to depend on file sizes any larger than absolutely necessary. Most major JavaScript component libraries and toolkits now have some form of custom build option. You can create a custom jQuery build by checking our different Git branches of their repository and running a local build. Bootstrap and Angular-UI Bootstrap allow you to create a custom build by selecting or deselecting individual modules via their web interface. Only the collection of selected components and necessary dependencies will be included in the files you receive.

The following additions to our Gruntfile.js include tasks and functions for JavaScript minification, file concatenation, and build options for the entire library or just a sub-set of UI components.

7.6 Minification, Concatenation, and Build Tasks Added to Gruntfile.js

// configure the tasks

grunt.initConfig({

// external library versions

ngversion: '1.2.16',

components: [],

//to be filled in by build task

libs: [],

//to be filled in by build task

dist: 'dist',

filename: 'ui-components',

filenamecustom: '<%= filename %>-custom',

// make the NPM configs available as vars

pkg: grunt.file.readJSON('package.json'),

srcDir: 'src/',

buildSrcDir: 'build/src/',

// keep a module:filename lookup table since there isn's

// a regular naming convention to work with

// all small non-component and 3rd party libs

// MUST be included here for build tasks

libMap: {

"ui.bootstrap.custom":"ui-bootstrap-collapse.js",

"ngSanitize":"angular-sanitize.min.js"

},

meta: {

modules: 'angular.module("uiComponents", [<%= srcModules %>]);',

all: '<%= meta.srcModules %>',

banner: ['/*',

' * <%= pkg.name %>',

' * <%= pkg.repository.url %>\n',

' * Version:

<%= pkg.version %> - <%= grunt.template.today("yyyy-mm-dd") %>',

' * License: <%= pkg.license %>',

' */\n'].join('\n')

},

uglify: {

options: {

banner: '<%= meta.banner %>',

mangle: false,

sourceMap: true

},

dist:{

src:['<%= concat.comps.dest %>'],

dest:'<%= dist %>/<%= filename %>-<%= pkg.version %>.min.js'

}

},

concat: {

// it is assumed that libs are already minified

libs: {

src: [],

dest: '<%= dist %>/libs.js'

},

// concatenate just the modules, the output will

// have libs prepended after running distFull

comps: {

options: {

banner: '<%= meta.banner %><%= meta.modules %>\n'

},

//src filled in by build task

src: [],

dest: '<%= dist %>/<%= filename %>-<%= pkg.version %>.js'

},

// create minified file with everything

distMin: {

options: {},

//src filled in by build task

src: ['<%= concat.libs.dest %>','<%= uglify.dist.dest %>'],

dest: '<%= dist %>/<%= filename %>-<%= pkg.version %>.min.js'

},

// create unminified file with everything

distFull: {

options: {},

//src filled in by build task

src: ['<%= concat.libs.dest %>','<%= concat.comps.dest %>'],

dest: '<%= dist %>/<%= filename %>-<%= pkg.version %>.js'

}

}

});

// Credit portions of the following code to UI-Bootstrap team

// functions supporting build-all and build custom tasks

var foundComponents = {};

var _ = grunt.util._;

// capitalize utility

function ucwords (text) {

return text.replace(/^([a-z])|\s+([a-z])/g, function ($1) {

return $1.toUpperCase();

});

}

// uncapitalize utility

function lcwords (text) {

return text.replace(/^([A-Z])|\s+([A-Z])/g, function ($1) {

return $1.toLowerCase();

});

}

// enclose string in quotes

// for creating "angular.module(..." statements

function enquote(str) {

return '"' + str + '"';

}

function findModule(name) {

// by convention, the "name" of the module for files, dirs and

// other reference is Capitalized

// the nme when used in AngularJS code is not

name = ucwords(name);

// we only need to process each component once

if (foundComponents[name]) { return; }

foundComponents[name] = true;

// add space to display name

function breakup(text, separator) {

return text.replace(/[A-Z]/g, function (match) {

return separator + match;

});

}

// gather all the necessary component meta info

// todo - include doc and unit test info

var component = {

name: name,

moduleName: enquote('uiComponents.' + lcwords(name)),

displayName: breakup(name, ' '),

srcDir: 'src/' + name + '/',

buildSrcDir: 'build/src/' + name + '/',

buildSrcFile: 'build/src/' + name + '/' + name + '.js',

dependencies: dependenciesForModule(name),

docs: {} // get and do stuff w/ assoc docs

};

// recursively locate all component dependencies

component.dependencies.forEach(findModule);

// add this component to the official grunt config

grunt.config('components', grunt.config('components')

.concat(component));

}

// for tracking misc non-component and 3rd party dependencies

// does not include main libs i.e. Angular Core, jQuery, etc

var dependencyLibs = [];

function dependenciesForModule(name) {

var srcDir = grunt.config('buildSrcDir');

var path = srcDir + name + '/';

var deps = [];

// read in component src file contents

var source = grunt.file.read(path + name + '.js');

// parse deps from "angular.module(x,[deps])" in src

var getDeps = function(contents) {

// Strategy: find where module is declared,

// and from there get everything i

// nside the [] and split them by comma

var moduleDeclIndex = contents

.indexOf('angular.module(');

var depArrayStart = contents

.indexOf('[', moduleDeclIndex);

var depArrayEnd = contents

.indexOf(']', depArrayStart);

var dependencies = contents

.substring(depArrayStart + 1, depArrayEnd);

dependencies.split(',').forEach(function(dep) {

// locate our components that happen to be deps

// for tracking by grunt.config

if (dep.indexOf('uiComponents.') > -1) {

var depName = dep.trim()

.replace('uiComponents.','')

.replace(/['"]/g,'');

if (deps.indexOf(depName) < 0) {

deps.push(ucwords(depName));

// recurse through deps of deps

deps = deps

.concat(dependenciesForModule(depName));

}

// attach other deps to a non-grunt var

} else {

var libName = dep.trim().replace(/['"]/g,'');

if(libName && !_.contains(dependencyLibs ,libName) ){

dependencyLibs.push(libName);

}

}

});

};

getDeps(source);

return deps;

}

grunt.registerTask('build', 'Create component build files', function() {

// map of all non-component deps

var libMap = grunt.config('libMap');

// array of the above to include in build

var libFiles = grunt.config('libs');

var fileName = '';

var buildSrcFiles = [];

var addLibs = function(lib){

fileName = 'lib/' + libMap[lib];

libFiles.push(fileName);

};

//If arguments define what modules to build,

// build those. Else, everything

if (this.args.length) {

this.args.forEach(findModule);

_.forEach(dependencyLibs, addLibs);

grunt.config('filename', grunt.config('filenamecustom'));

// else build everything

} else {

// include all non-component deps in build

var libFileNames = _.keys(grunt.config('libMap'));

_.forEach(libFileNames, addLibs);

}

grunt.config('libs', libFiles);

var components = grunt.config('components');

// prepare source modules for custom build

if(components.length){

grunt.config('srcModules', _.pluck(components, 'moduleName'));

buildSrcFiles = _.pluck(components, 'buildSrcFile');

// all source files for full library

}else{

buildSrcFiles = grunt.file.expand([

'build/src//*.js',

'!build/src//*.tpl.js',

'!build/src//test/*.js'

]);

// prepare module names for "angular.module('',[])" in build file

var mods = [];

_.forEach(buildSrcFiles, function(src){

var filename = src.replace(/^.*[\\\/]/, '')

.replace(/\.js/,'');

filename = enquote('uiComponents.' + lcwords(filename));

mods.push(filename);

})

grunt.config('srcModules', mods);

}

// add src files to concat sub-tasks

grunt.config('concat.comps.src', grunt.config('concat.comps.src')

.concat(buildSrcFiles));

grunt.config('concat.libs.src', grunt.config('concat.libs.src')

.concat(libFiles));

// time to put it all together

grunt.task.run([

'karma:unit',

'concat:libs',

'concat:comps',

'uglify',

'concat:distMin',

'concat:distFull'

]);

});

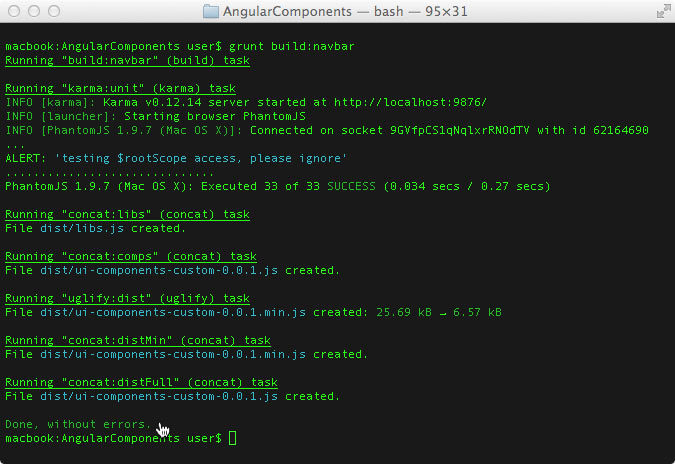

If we run a custom build task, and all goes well, we should see something like the following:

Console output for grunt build:navbar command

The additions to the Gruntfile.js in bold illustrate the complexity of adding custom build options for a subset of UI component to the command line as component name arguments. Much of this code deals with finding the UI components that match the names, parsing components to get the dependency references from the code, and then finding the dependency files, and doing the same recursively until all dependencies are resolved. It’s basically the same algorithm that AngularJS performs in the browser upon load to resolve all of the referenced modules.

Gruntfile.js Odds, Ends, and Issues

The code above makes significant use of Grunt templates such as:

’<%= dist %>/<%= filename %>-<%= pkg.version %>.js’

to dynamically fill in the list of input files from the previous task’s list of output files. If you are familiar with ERB, Underscore, or Lodash templates, the delimiters are the same. This save us from having to write a lot of code to manage variable input and output file lists.

Even with this code savings, our Gruntfile.js has still grown to hundreds of lines of JavaScript, making it hard for other engineers to grok quickly. There are still many tasks and sub-tasks yet to configure in a “real world” situation that could add a few hundred more lines of code. Fortunately, there is a Grunt plugin called load-grunt-config which allows you to break up large Gruntfile.js’ by factoring out tasks into their own files. The NPM page for this module shows how to use it.

https://www.npmjs.org/package/load-grunt-config

For the remainder of this chapter, we will use a single, monolithic Gruntfile.js for concept illustrative purposes, however, if adapting this Gruntfile.js for use with an actual UI component library, factoring out tasks into their own files should be on the todo list.

Custom Build GUIs

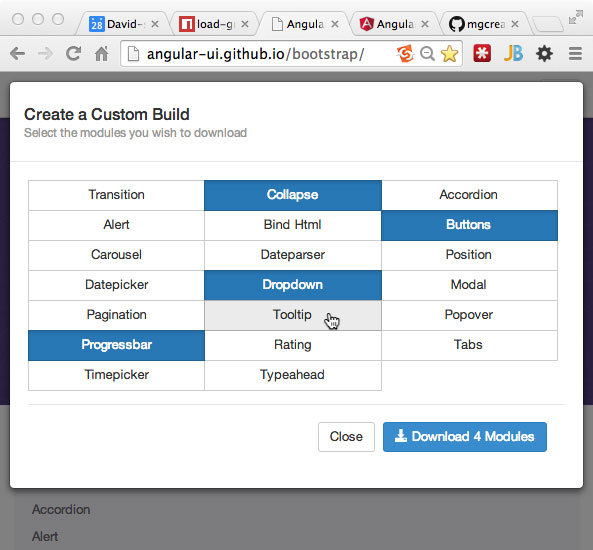

Now that we have custom build capability, it’s fairly trivial for us to add a web GUI interface so our customers can just check the boxes for the set of UI components needed, and then zip and serve the built files as the response. For a working example, you can check out the AngularUI Bootstrap page (upon which much of the example build task code is based) and select the “Create a Build” option to get an idea. The result will be full and minified module and template files (4 files).

http://angular-ui.github.io/bootstrap/

Screen grabs of the AngularUI team’s custom build GUI

Creating a web interface similar to the example from UI-Bootstrap is the way to go, given that one of the major themes of this book is creating UI component libraries that are as simple as possible for web page designers to integrate and use, making them easy to propagate throughout an enterprise sized organization. We expect that our customers are not all senior level web developers, so we want to avoid having to checkout Git branches and running builds, or having to enter command line arguments (with correct spelling and case) to get a custom build.

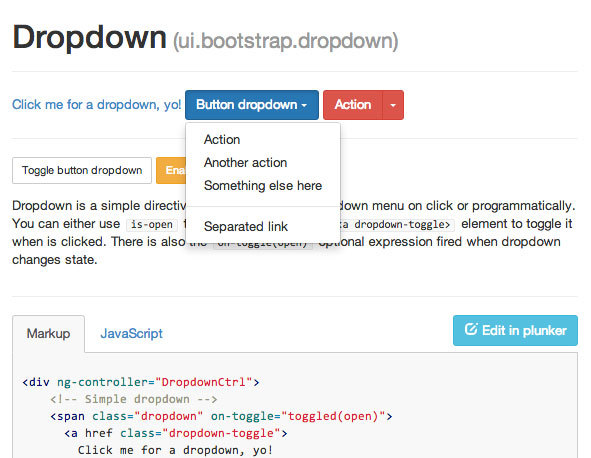

Also, as part of the website for our UI component library that customers will interact with, we must include, not just API documentation, but also HTML and JavaScript examples of each component. The examples should visually illustrate the various states and API options of each component in action. The HTML should illustrate where to place the custom elements, and what to place inside them. Again, using the same AngularUI-Bootstrap page, something like the following, in addition to the API documentation example from the previous chapter, should work:

Example section from the AngularUI Bootstrap team’s site shown their dropdown usage

At the beginning of this chapter, we included a source documentation folder as part of the suggested UI component library source directory structure where the files that illustrate example usage should live. A dropdown.demo.html file and a dropdown.demo.js file would map to the content for the two tabs in the screen grab above.

Additional Grunt Tasks

At the time of this writing there are exactly 2,928 registered Grunt plugins of which we have worked with 8 including the two that we forked for our own customizations. There are some useful plugins for build automation tasks we have not yet covered including generating documentation, adding change-log entries, version “bumping”, cleaning build artifacts, creating zip files for down load, and more.

Unfortunately we can only dedicate part of a chapter on task automation with Grunt, enough to give a high level overview, to cover task very unique to our needs, and to provide code examples to help you get a start with task and build automation for your own UI component library.

There are a handful of books dedicated entirely to Grunt. However, I believe the best source of information about what you can automate with existing task is to just Google what you need, check out the Grunt plugin page http://gruntjs.com/plugins, and check out Gruntfile.js’ from public repositories of project similar to your own. If time and space permitted, we would also cover the following list of plugins, and hopefully some or all of them will see use in the example GitHub repository for this book by the time it is published (in addition to our own tasks being registered as official Grunt plugins):

- grunt-contrib-clean - delete unneeded build generated files

- grunt-conventional-changelog - maintain a change log from version to version

- grunt-contrib-copy - for miscellaneous file copying to other locations

- grunt-contrib-cssmin - minify the CSS output from LESS source

- grunt-bump - uses Sem(antic)Ver(sioning) to bump up release numbers

- grunt-contrib-livereload - automatically reload test page on file save

- grunt-jsdoc - generate parts of the API docs from jsDoc comments in the source code (possibly extend to add tags that handle non-standard APIs)

Gulp.js - The Streaming Build System

If you scan the build tasks in our Gruntfile.js, you may notice that in the process of merging templates with code, concatenating it, minifying it, and merging with the concatenated library file, Grunt is reading and writing to disc four times! If our library grows to hundreds of source files, builds can start taking quite a while.

Since about mid-2013, Gulp.js has risen up as an alternative to Grunt, in part, to bypass all of the unnecessary disc I/O. It takes advantage of data streams and “pipes” to stream the output from one task directly to the next task as an input data stream rather than stream the data to the file system in between. I have to admit that when I began reading about Gulp.js, I started having horrid flashbacks to my Unix sysadmin and Java programming days. The upside to those flashbacks was that I already understood pipes from Unix and Streams from Java. Java has extensive libraries for handling data streams of all types. I was surprised to find out that granular manipulation of data streams were not a part of Node.js until version 0.10+.

The following code listing contains a sample gulpfile.js forked from a GitHub Gist by Mark Goodyear:

https://gist.github.com/markgoodyear/8497946

7.7 Example gulpfile.js File

// Load plugins

var gulp = require('gulp'),

sass = require('gulp-ruby-sass'),

autoprefixer = require('gulp-autoprefixer'),

minifycss = require('gulp-minify-css'),

jshint = require('gulp-jshint'),

uglify = require('gulp-uglify'),

imagemin = require('gulp-imagemin'),

rename = require('gulp-rename'),

clean = require('gulp-clean'),

concat = require('gulp-concat'),

notify = require('gulp-notify'),

cache = require('gulp-cache'),

livereload = require('gulp-livereload'),

lr = require('tiny-lr'),

server = lr();

// Styles

gulp.task('styles', function() {

return gulp.src('src/styles/main.scss')

.pipe(sass({ style: 'expanded', }))

.pipe(autoprefixer('last 2 version', 'safari 5', 'ios 6', 'android 4'))

.pipe(gulp.dest('dist/styles'))

.pipe(rename({ suffix: '.min' }))

.pipe(minifycss())

.pipe(livereload(server))

.pipe(gulp.dest('dist/styles'))

.pipe(notify({ message: 'Styles task complete' }));

});

// Scripts

gulp.task('scripts', function() {

return gulp.src('src/scripts//*.js')

.pipe(jshint('.jshintrc'))

.pipe(jshint.reporter('default'))

.pipe(concat('main.js'))

.pipe(gulp.dest('dist/scripts'))

.pipe(rename({ suffix: '.min' }))

.pipe(uglify())

.pipe(livereload(server))

.pipe(gulp.dest('dist/scripts'))

.pipe(notify({ message: 'Scripts task complete' }));

});

// Images

gulp.task('images', function() {

return gulp.src('src/images//*')

.pipe(cache(imagemin({ o

ptimizationLevel: 3,

progressive: true,

interlaced: true })))

.pipe(livereload(server))

.pipe(gulp.dest('dist/images'))

.pipe(notify({

message: 'Images task complete'

}));

});

// Clean

gulp.task('clean', function() {

return gulp.src([

'dist/styles',

'dist/scripts',

'dist/images'

], {read: false})

.pipe(clean());

});

// Default task

gulp.task('default', ['clean'], function() {

gulp.run('styles', 'scripts', 'images');

});

// Watch

gulp.task('watch', function() {

// Listen on port 35729

server.listen(35729, function (err) {

if (err) {

return console.log(err)

};

// Watch .scss files

gulp.watch('src/styles//*.scss', function(event) {

console.log('File ' +

event.path +

' was ' +

event.type +

', running tasks...');

gulp.run('styles');

});

// Watch .js files

gulp.watch('src/scripts//*.js', function(event) {

console.log('File ' + event.path + ' was ' +

event.type +

', running tasks...');

gulp.run('scripts');

});

// Watch image files

gulp.watch('src/images//*', function(event) {

console.log('File ' + event.path + ' was ' +

event.type + ', running tasks...');

gulp.run('images');

});

});

});

The code listing above has nothing to do with our sample UI component library. It is included to provide a contrast of the syntax between Grunt and Gulp.js. Mark Goodyear also has an excellent Gulp.js introductory blog post at:

http://markgoodyear.com/2014/01/getting-started-with-gulp/

Gulp.js Pros

Gulp.js’ major selling point is plugins that can input and output data streams which can be chained with pipes, offering much faster build automation for industrial sized projects. Additionally, if the function functionality for a given task already exists as a Node.js library or package, it can be “required()” and used directly, no need to wrap as a grunt-task.

Gulp.js’ other selling points are a matter of opinion based on what type of programming and languages you are most comfortable with. Grunt is object “configuration” based, whereas, Gulp.js utilizes attributes of functional and imperative programming to define tasks and workflows. Developers who spend most of the day using Node.js are generally more comfortable with the latter. Those who have used systems such as Ant, Maven, Rake, YML or any other system after the days of Make (which was basically shell programming) are probably more comfortable with the former.

Another major difference between Grunt and Gulp.js is that by default, dependencies for a Grunt task are executed in sequence by default. Dependencies for a Gulp.js task are executed concurrently, or in parallel, by default. Executing non-interdependent tasks concurrently can shave time off of builds, but requires special handling in Gulp.js with deferreds or callbacks (called “hints”).

Finally, if you cannot find a Gulp.js plugin that does what your Grunt plugin does, there is a Gulp.js plugin that wraps Grunt plugins called gulp-grunt.

Gulp.js Cons

The basic Gulp.js tasks as of this writing seem to be immature. I was unable to get “gulp-include” to work with piped output from a concat task as it did not know how to resolve the include file’s path. I could only get it to work with the files read from and written to disc which defeats the purpose of Gulp.js. Overall, the core Grunt tasks are much more tried and true.

The documentation for Gulp.js is extremely minimal, I suppose because the assumption is that you should have sufficient knowledge of I/O programming with Node.js. The majority of front-end developers, myself included, are not “intimate” with Node’s inner I/O workings. As much as I wanted to debug the issue with the gulp-include plugin, I didn’t know where to start other than taking a deep dive into Node.js’ I/O library docs. As mentioned earlier, at this time, Gulp seems to have a much higher level of accessibility to the Node.js vs. non-Node.js communities.

The Gulp team touts that plugins for Gulp.js are held to “stringent” standards, and it looks like several plugins that have been written for Gulp on their search page are crossed out with red labels indicating that they are duplicates of another plugin or don’t comply with some rule that is required by the Gulp team. If you click the red label, it takes you to a GitHub open-an-issue page where you need to explain why this plugin should be removed from the “blacklist”.

Given that anyone who takes the time to contribute to open-source is doing so on their spare time, and for free, this strikes me as both insulting and elitist. I personally would not bother to spend the time and effort on contributing to this project given the core team’s attitude. I’m including this commentary; not as a rant, but to illustrate that this attitude towards contributions would likely alienate a lot of would-be, plugin contributors.

I personally would like to see stream and pipe capability added to Grunt. Performance for large builds is the one real downside to Grunt from a pragmatic point of view. The other downsides claimed by the Gulp community essentially boil down to opinion.

Continuous Integration and Delivery

So far we have covered all the necessary tool categories needed from the time we edit a source file to the end result of a built and minified file of our UI component library on our local development environment. Unless we are also the only customer for our library, there is still more to be done in order to get our code into the hands of our customers.

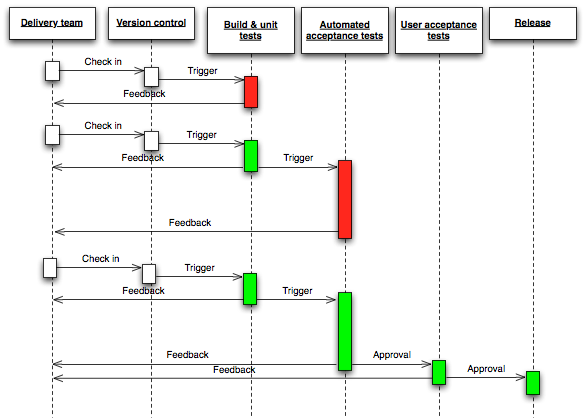

Continuous integration and delivery is considered the current best practice in web application development. Continuous integration (CI) grew out of XP (Extreme Programming) of the late 90s. Today, most organizations practice CI without XP. The idea is to kick off an automated test and build upon a source code commit to the main branch on a central integration server at a minimum. While code in a developer’s local environment may test and build without error, unless the environment is identical to build, staging, and production servers, as well as all major browsers, errors may arise in builds performed after the code leaves the developer’s laptop. The central build upon commit helps identify any breakage caused by the commit so everyone can see it. More often than not, developers who are either lazy or arrogant feel they can get away with the local quality checks prior to a commit. CI helps catch the breakage and who caused it, so they can be publically shamed and hopefully learn to respect best practices more. Besides the public humiliation for the developer who broke the codebase, CI help prevent nasty regression bugs from making their way into production. These are the defects that can be very difficult to trace back to a source given that in web development multiple languages are employed and must work together to produce what is delivered to the customer.

CI usually goes beyond just a central test-then-build process. Once the build is produced, an additional round of integration and end-to-end tests on multiple servers, and in all supported browsers happens. Following that is typically some sort of a deployment to a staging environment, or even to production as a “snapshot” release. Some of the more popular integration applications include Jenkins, Continuum, Gump, TeamCity, and the one we will be using, Travis-CI.

For a more in depth introduction to CI check out the Wikipedia page:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Continuous_integration

A flow representation of continuous delivery

Travis-CI

Travis-CI is one of the many cloud based CI systems that have sprung up in recent years. It provides runtime environments for multiple versions of most popular languages including Node.js/JavaScript. Travis-CI provides free service for public GitHub repositories, and you log in using your GitHub account, which is the first step to setting up a watch for the repository that needs continuous integration. Once logged in, you can choose which repos for Tavis-CI to watch. The next step is creating and validating a Travis-CI configuration file (.travis.yml) in the root directory of the repo to watch.

Travis-CI configuration for client-side code bases is simple. It can get more involved when you add servers and databases. You can validate your configuration with a linting tool available from them. Most of the work that actually takes place on the Tavis-CI server is what was defined in your Grunt/Gulp file and package.json. The next step to initiate continuous integration and deployment for your project is to make a commit. You can

7.8 Travis-CI Configuration (.travis.yml) for Our Project

language: node_js

node_js:

- "0.10"

before_script:

- export DISPLAY=:99.0

- sh -e /etc/init.d/xvfb start

- npm install --quiet -g grunt-cli karma

- npm install

script: grunt

Given the contents of our .travis.yml file above we can start to piece together the CI workflow steps.

- Make a code commit

- Travis-CI instantiates a transient VM the exists only for the length of the workflow

- A Node.js version 0.10 runtime is instantiated as per the language requirement

- Some pre-integration set up takes place

- a fake display is added to the VM for message I/O (- export DISPLAY=:99.0; - sh -e /etc/init.d/xvfb start)

- Grunt and Karma are installed globally (- npm install –quiet -g grunt-cli karma)

- all development dependencies listed in packge.json are installed via NPM (- npm install)

- The default Grunt task from our Gruntfile.js runs (script: grunt)

We are only using two of the available break points in Travis-CI’s lifecycle. The other break points where commands can be executed include: before_install, install, before_script, script, after_script, after_success, or after_failure, after_deploy.

If any Grunt tasks fail in this environment, the build will be marked as failed. If you have the Tavis-CI badge in your Readme.md file, it will display a green, build-passing image or a red, build-failing image. Common causes of failures include unlisted dependencies in package.json and inability to find files or directories during tests or build due to relative path problems. Builds can take several minutes to complete depending on the current Travis-CI workload, how many dependencies need to download, and amount of file I/O.

Travis-CI and some of the other cloud based CI systems that integrate with GitHub, are great continuous integration solutions for developers who’d rather spend the bulk of their time on coding rather than development operations. On the other hand, if you are on a larger team with a dedicated devOps engineer and servers behind a firewall, then dedicated, configurable CI systems like Jenkins or TeamCity offer a lot more flexibility.

You might be asking where is the deployment or delivery? Travis-CI will optionally transfer the designated distribution files to various cloud hosts such as Heroku. For our immediate purposes we are only using Travis-CI for continuous integration or build verification so we know that nothing should be broken if others clone the main repository and run a build.

There are multiple ways our library could be deployed:

- Via direct download of a zipfile from a server

- Via public CDN (content delivery network)

- As a check out or clone directly from GitHub

- Via a package repository such as Bower

Given that we are offering both the complete library, and custom subsets of components we will need to use two of the methods above. For custom builds we would need to create a GUI front-end to the Grunt CLI command for custom builds and use a web hosting account that clones the main Git Repository behind the scenes. For complete versions of the library, we can take advantage of a package management repository of which Bower is the most appropriate.

Bower Package Registry