Chapter 8 - W3C Web Components Tour

Beginning in 2012 there has been serious chatter on all the usual developer channels about something called Web Components. The term might already sound familiar to you from both Microsoft and Sun Microsystems. Microsoft used the term to describe add-ons to Office. Sun (now Oracle) used the term to describe Java, J2EE servlets. Now the term is being used to refer to a set of W3C draft proposals for browser standards that will allow developers to accomplish natively in the browser what we do today with JavaScript UI frameworks.

The Roadmap to Web Components

As the AJAX revolution caught on, and data was being sent to browsers asynchronously, technics for displaying the data using the tools browsers provided (JavaScript, CSS, and HTML) needed development. Thus, client-side UI widget frameworks arose including DOJO, jQuery UI, ExtJS, and AngularJS. Some of the early innovations by the DOJO team really stood out. They developed modules to abstract AJAX and other asynchronous operations (promises and deferreds. On top of that, they developed an OO based UI widget framework that allowed widget instantiation via declarative markup. Using DOJO you could build full client-side applications out of modules they provided in a fraction of the time it took to write all of the low level code by hand. Furthermore, using DOJO provided an abstraction layer for different browser incompatibilities.

While DOJO provided a “declarative” option for their framework, other framework developers took different approaches. jQuery UI, built on top of jQuery, was imperative. GWT (Google Windowing Toolkit) generated the JavaScript from server-side code, and ExtJS was configuration based. AngularJS largely built upon the declarative approach that DOJO pioneered.

A lot of brilliant thinking and hard work has gone into client-side frameworks over the last decade. As we mentioned earlier, there are literally thousands of known client-side UI frameworks out there, and huge developer communities have sprung up around those in the top ten.

Sadly though, at the end of the day (or decade) all of this brilliance and work adds up to little more than hacks around the limitations of the browser platforms themselves. If the browser vendors had built in ways to encapsulate, package, and re-use code in HTML and DOM APIs at the same time as AJAX capability, modern web development would be a very different beast today. Be as it may, browser standards progress in a “reactive” manner. Semantic HTML5 tags like <header> and <nav> only became standards after years of <div class="header"> and <div class="nav">.

Now that we’ve had workarounds in the form of UI frameworks for the better part of the last decade that handle tasks like templating, encapsulation, and data-binding, the standards committees are now discussing adding these features to ECMA Script and the DOM APIs. While still a couple years away from landing in Internet Explorer, we are starting to get prototype versions of these features in Chrome and Firefox that we can play with now.

The set of specifications falling under the “Web Components” umbrella include:

- The ability to create custom elements with the option of extending existing elements

- A new

<template>tag to contain inert, reusable chunks of HTML, JavaScript, and CSS for lazy DOM insertion - A way to embed a DOM tree within a DOM tree called shadow DOM that provides encapsulation like an iframe without all the overhead

- The ability (called HTML imports) to load HTML documents that contain the items above in an HTML document

The above proposed standards are under the domain of the W3C. A closely related standard under the domain of the ECMA are additions to the Object API that allow property mutations to be tracked natively that folks are referring to as “Object.observe()”. Object.observe() is proposed for ES7 which is a ways off. ES6, which is already starting to be implemented in Firefox and Node.js, will add long-awaited conveniences like modules and classes for easier code reuse in Web Components.

Certain forward looking framework authors, including the AngularJS team, are well aware of the proposed standards and are now incorporating them into their product roadmaps.

Disclaimers and Other CYA Stuff

While we will be covering some detailed examples of Web Component standards implementation, the intent is to present what’s to come at a high level or abstracted somewhat from the final APIs. The actual standards proposals are still in a very high state of flux. The original proposals for <element> and <decorator> tags have been shelved due to unforeseen implementation issues. Other proposals are still experiencing disagreement over API details. Therefore, any and all examples in this section should be considered as pseudo-code for the purposes of illustrating the main concepts, and there is no guarantee of accuracy.

The W3C maintains a status page for the Web Components drafts at:

http://www.w3.org/standards/techs/components#w3c_all

This page has links to the current status of all the proposals.

This presentation is also intended to be unbiased from an organization standpoint. The Web Components proposals have been largely created, supported and hyped by members of Google’s Chrome development team with positive support from Mozilla. Apple and Microsoft, on the other hand, have been largely silent about any roadmap of support for these standards in their browsers. The top priority for the latter two companies is engineering their browsers to leverage their operating systems and products, so they will be slower to implement. Browser technology innovations are more central to Google’s and Mozilla’s business strategy.

At the time of this writing, your author has no formal affiliation with any of these organizations. The viewpoint presented is that of a UI architect and engineer who would be eventually implementing and working with these standards in a production setting. Part of this viewpoint is highly favorable towards adopting these standards as soon as possible, but that is balanced by the reality that it could still be years before full industry support is achieved. Any hype from Google that you can start basing application architecture on these standards and associated polyfills in the next six months or year should be taken with a grain of salt.

Just about everyone is familiar with the SEC disclaimer about “forward looking statements” that all public companies must include with any financial press releases. That statement can be safely applied to the rest of the chapter in this book.

The Stuff They Call “Web Components”

In the following sections we will take a look at the specifics of W3C proposal technologies. This will include overviews of the API methods current at the time of writing plus links to the W3C pages where the drafts proposals in their most current state can be found. If you choose to consult these documents, you should be warned that much of their content is intended for the engineers and architects who build browsers. For everyone else, it’s bedtime reading, and you may fall asleep before you can extract the information relevant to web developers.

The example code to follow should, for the most part, be executable in Chrome Canary with possible minor modification. It can be downloaded at the following URL.

http://www.google.com/intl/en/chrome/browser/canary.html

Canary refers to what happens to them in coal mines. It is a version of Chrome that runs a few versions ahead of the official released version and contains all kinds of features in development or experimentation including web component features. Canary can be run along side official Chrome without affecting it. It’s great for getting previews of new feature, but should never, ever be used for regular web browsing as it likely has a lot of security features turned off. Then again, if you have a co-worker you dislike greatly, browsing the net with it from their computer is probably ok.

Custom Elements

Web developers have been inserting tags with non-standard names into HTML documents for years. If the name of the tag is not included in the document’s DOCTYPE specification, the standard browser behavior is to ignore it when it comes to rendering the page. When the markup is parsed into DOM, the tag will be typed as HTMLUnknownElement. This is what happens under the covers with AngularJS element directives such as <uic-menu-item> that we used as example markup earlier.

The current proposal for custom element capability includes the ability to define these elements as first class citizens of the DOM.

http://www.w3.org/TR/custom-elements/

Such elements would inherit properties from HTMLElement. Furthermore, the specification includes the ability to create elements that inherit from and extend existing elements. A web developer who creates a custom element definition can also define the DOM interface and special properties for the element as part of the custom element’s prototype object. The ability to create custom elements combined with the additions of classes and modules in ES6 will become a very powerful tool for component developers and framework authors.

Registering a Custom Element

As of the time of this writing, registering custom elements is done imperatively via JavaScript. A proposal to allow declarative registration via an <element> tag has been shelved due to timing issues with document parsing into DOM. This is not necessarily a bad thing since an <element> tag would encourage “hobbyists” to create pages full of junk. By requiring some knowledge of JavaScript and the DOM in order to define a new element, debugging someone else’s custom element won’t be as bad.

There are three simple steps to registering a custom element.

- Create what will be its prototype from an existing HTMLElement object

- Add any custom markup, style, and behavior via it’s “created” lifecycle callback

- Register the element name, tag name, and prototype with the document

A tag that matches the custom element may be added to the document either before or after registration. Tags that are added before registration are considered “unresolved” by the document, and then automatically upgraded after registration. Unresolved elements can be matched with the :unresolved CSS pseudo class as a way to hide them from the dreaded FOUC (flash of unstyled content) until the custom element declaration and instantiation.

8.0 Creating a Custom Element in its Simplest Form

<script>

// Instantiate what will be the custom element prototype

// object from an element prototype object

var MenuItemProto = Object.create( HTMLElement.prototype );

// browsers that do not support .registerElement will

// throw an error

try{

// call registerElement with a name and options object

// the name MUST have a dash in it

var MenuItem = document.registerElement( 'menu-item', {

prototype: MenuItemProto

});

}catch(err){}

</script>

<!-- add matching markup -->

<menu-item>1</menu-item>

<menu-item>2</menu-item>

<menu-item>3</menu-item>

Listing 8.0 illustrates the minimal requirements for creating a custom element. Such an element will not be useful until we add more to the definition, but we can now run the following in the JavaScript console which will return true:

document.createElement('menu-item').__proto__ === HTMLElement

versus this for no definition or .registerElement support:

document.createElement('menuitem').__proto__ === HTMLUnknownElement

8.1 Extending an Existing Element in its Simplest Form

<script>

// Instantiate what will be the custom element prototype

// object from an LI element prototype object

var MenuItemProto = Object.create( HTMLLIElement.prototype );

// browsers that do not support .registerElement will

// throw an error

try{

// call registerElement with a name and options object

// the name MUST have a dash in it

var MenuItem = document.registerElement( 'menu-item', {

prototype: MenuItemProto,

extends: 'li'

});

}catch(err){}

</script>

<!-- add matching markup -->

<li is="menu-item">1</li>

<li is="menu-item">2</li>

<li is="menu-item">3</li>

Listing 8.1 illustrates the minimal steps necessary to extend an existing element with differences in bold. The difference here is that these elements will render to include any default styling for an <li> element, typically a bullet. In this form parent element name “li” must be used along with the “is=”element-type” attribute.

It is still possible to extend with HTMLLIElement to get access to its methods and properties without the extends: ‘li’ in order to use the <menu-item> tag, but it will not render as an <li> tag by default. Elements defined by the method in the latter example are called “type extention elements”. Elements created similar to the former example are called “custom tags”. In both cases it must be noted that custom tag names must have a dash in them to be recognized as valid names by the browser parser. The reasons for this are to distinguish custom from standard element names, and to encourage the use of a “namespace” name such as “uic” as the first part of the name to distinguish between source libraries.

If this terminology remains intact until widespread browser implementation, it will likely be considered a best-practice or rule-of-thumb to use type extensions for use-cases where only minor alterations to an existing element are needed. Use-cases calling for heavy modification of an existing element would be better served descriptively and declaratively as a custom tag. Most modern CSS frameworks, such as Bootstrap, select elements by both tag name and class name making it simple to apply the necessary styling to custom tag names.

Element Lifecycle Callbacks and Custom Properties

Until now the custom element extension and definition examples are not providing any value-add. The whole point of defining custom elements, and ultimately custom components, is to add the properties and methods that satisfy the use-case. This is done by attaching methods and properties to the prototype object we create, and by adding logic to a set of predefined lifecycle methods.

8.2 Custom Element Lifecycle Callbacks

<script>

// Instantiate what will be the custom element prototype

// object from an element prototype object

var MenuItemProto = Object.create(HTMLElement.prototype);

// add a parent component property

MenuItemProto.parentComponent = null;

// lifecycle callback API methods

MenuItemProto.created = function() {

// perform logic upon registration

this.parentComponent = this.getAttribute('parent');

// add some content

this.innerHTML = "<a>add a label later</a>";

};

MenuItemProto.enteredView = function() {

// do something when element is inserted

// in the DOM

};

MenuItemProto.leftView = function() {

// do something when element is detached

// from the DOM

};

MenuItemProto.attributeChanged = function(attrName, oldVal, newVal){

// do something if an attribute is

// modified on the element

};

// browsers that do not support .registerElement will

// throw an error

try{

// call registerElement with a name and options object

var MenuItem = document.registerElement('menu-item', {

prototype: MenuItemProto

});

}catch(err){}

</script>

<menu-item parent="drop-down"></menu-item>

The proposed custom element specifications include a set of lifecycle callback method names. The actual names are in a state of flux. The ones in bold in the example are current as of mid 2014. Whatever the final names are, there will most likely be a callback upon element registration where most logic should execute. Upon execution of this callback, :unresolved would no longer apply as a selector. The other callbacks will likely run upon DOM insertion, detachment from the DOM, and upon any attribute mutation. The parameters for attribute mutation events will likely be name plus old, and new values for use in any necessary callback logic.

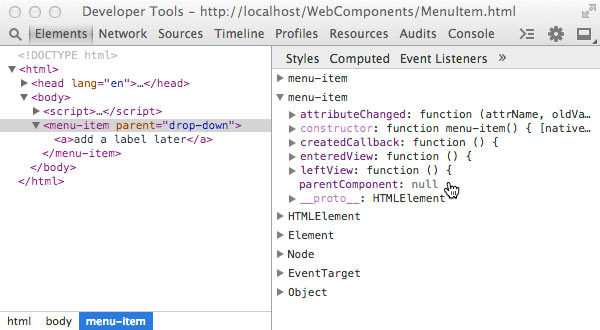

Inspection of the MenuItem prototyope object “parentComponent” property

Inspection of the <menu-item> “parentComponent” instance property

In the above example we are adding a parentComponent property to the element. The purpose would be analogous to the parentElement property except that a UI component hierarchy would likely have DOM hierarchies within each UI component. So “walking” the component hierarchy would not be the same as walking the DOM hierarchy. Along these lines, the example has us getting the parentComponent reference name from a “parent” attribute. It also has a simple example of directly adding some innerHTML. In actual practice, we would likely add any element content as shadow DOM via <template> tags as we will illustrate in the next sub-sections.

To recap on custom element definitions, they consist of the custom element type, the local name (tag name), the custom prototype, and lifecycle callbacks. They also may have an optional XML namespace prefix. Once defined, custom elements must be registered before their properties can be applied. Custom elements, while useful in their own right, will be greatly enhanced for use as UI components when they are used in combination with shadow DOM and template tags. Also, as mentioned earlier, plans for declarative definitions via an <element> tag have been shelved, but the Polymer framework has a custom version of the tag called <polymer-element> that can be used in a declarative fashion. We will explore Polymer and other polyfill frameworks in the next chapter.

Shadow DOM

I like to describe Shadow DOM as kind of like an iframe, but with out the “frame”.

Up to now the only way to embed third party widgets in your page with true encapsulation is inside a very “expensive” iframe. What I mean by expensive, is that an iframe consumes the browser resources necessary to instantiate an entirely separate window and document. Even including an entirely empty <iframe> element in a page is orders of magnitude more resource intensive than any other HTML element. Examples of iframe widgets can be social networking buttons like a Google+ share, a Twitter tweet, a Facebook like, or a Disqus comments block. They can also include non-UI marketing and analytics related apps.

Often times an iframe makes sense from a security standpoint if the content is unknown or untrusted. In those situations, you want to be able to apply CSP (content security policy) restrictions to the embedded frame. But iframes are also the only choice if you need to encapsulate your widget’s look and feel from the styling in the parent page even if there are no trust issues. CSS bleed is the largest obstacle when it comes to developing portable UI components meant to propagate a particular set of branding styles. Even the HTML in such components can be inadvertently altered or removed by code in the containing page. Only JavaScript, which can be isolated in an anonymous self-executing function is relatively immune from outside forces.

http://www.w3.org/TR/shadow-dom/

http://w3c.github.io/webcomponents/spec/shadow

Shadow DOM is a W3C specification proposal that aims to fill the encapsulation gap in modern browsers. In fact, all major browsers already use it underneath some of the more complex elements like <select> or <input type="date">. These tags have their own child DOM trees of which they are rendered from. The only thing missing is an API giving the common web developer access to the same encapsulation tools.

Like an extremely light-weight iframe

Shadow DOM provides encapsulation for the embedded HTML and CSS of a UI component. Logically the DOM tree in a Shadow DOM is seperate from the DOM tree of the page, so it is not possible to traverse into, select, and alter nodes from the parent DOM just like with the DOM of an embedded iframe. If there is an element with id=”comp_id” in the shadow DOM, you cannot use jQuery, $('#comp_id'), to get a reference. Likewise, CSS styles with that selector will not cross the shadow DOM boundary to match the element. The same holds true for certain events. In this regard, Shadow DOM is analogous to a really “light-weight” iframe.

That said, it is possible to traverse into the shadow DOM indirectly with a special reference to what is called the shadow root, and it is possible to select elements for CSS styling with a special pseudo class provided by the spec. But both of these tasks take conscious effort on the part of the page author, so inadvertent clobbering is highly unlikely.

JavaScript is the one-third of the holy browser trinity that behaves no different. Any <script> tags embedded in a shadow tree will execute in the same window context as the rest of the page. This is why shadow DOM would not be appropriate for untrusted content. However, given that JavaScript can already be encapsulated via function blocks in ES5 and via modules and classes in ES6, Shadow DOM provides the missing tools for creating high quality UI components for the browser environment.

Shadow DOM Concepts and Definitions

We have touched on the high-level Shadow DOM concepts above, but to really get our heads wrapped around the entire specification to the point where we can start experimenting, we need to introduce some more concepts and definitions. Each of these has a coresponding API hook that allows us to create and use shadow DOM to encapsulate our UI components. Please take a deep breath before continuing, and if you feel an anurysim coming on, then skip ahead to the APIs and examples!

Tree of Trees

The Document Object Model as we know it, is a tree of nodes (leaves). Adding shadow DOM means that we can now create a tree of trees. One tree’s nodes do not belong to another tree, and there is no limit to the depth. Trees can contain any number of trees. Where things get murky is when the browser renders this tree of trees. If you have been a good student of graph theory, then you’ll have a leg up groking these concepts.

Page Document Tree and Composed DOM

The final visual output to the user is that of a single tree which is called the composed DOM. However, what you see in the browser window will not seem to jibe with what is displayed in your developer tools, which is called the page document tree, or the tree of nodes above. This is because prior to rendering, the browser takes the chunk of shadow DOM and attaches it to a specified shadow root.

Shadow Root and Shadow Host

A shadow root is a special node inside any element which “hosts” a shadow DOM. Such an element is referred to as a shadow host. The shadow root is the root node of the shadow DOM. Any content within a shadow host element that falls outside of the hosted shadow DOM will not be rendered directly as part of the composed DOM, but may be rendered if transposed to a content insertion point described as follows.

Content and Shadow Insertion Points

A shadow host element may have regular DOM content, as well as, one or more shadow root(s). The shadow DOM that is attached to the shadow root may contain the special tags <content> and <shadow>. Any regular element content will be transposed into the <content> element body wherever it may be located in the shadow DOM. This is refered to as a content insertion point. This is quite analogous to using AngularJS ngTransclude except that rather than retaining the original $scope context, transposed shadow host content retains its original CSS styling. A shadow DOM is not limited to one content insertion point. A shadow DOM may have several <content> elements with a special select="css-selector" attribute that can match descendent nodes of the shadow host element, causing each node to be transposed to the corresponding content insertion point. Such nodes can be refered to as distributed nodes.

Not only may a shadow host element have multiple content insertion points, it may also have multiple shadow insertion points. Multiple shadow insertion points end up being ordered from oldest to youngest. The youngest one wins as the “official” shadow root of the shadow host element. The “older” shadow root(s) will only be included for rendering in the composed DOM if shadow insertion points are specifically declared with the <shadow> tag inside of the youngest or official shadow root.

Shadow DOM APIs

The following is current as of mid 2014. For the latest API information related to Shadow DOM please check the W3C link at the top of this section. The information below also assumes familiarity with the current DOM API and objects including: Document, DocumentFragment, Node, NodeList, DOMString, and Element.

From a practical standpoint we will start with the extensions to the current Element interface.

Element.createShadowRoot() - This method takes no parameters and returns a ShadowRoot object instance. This is the method you will likely use the most when working with ShadowDom given that there currently is no declarative way to instantiate this type.

Element.getDestinationInsertionPoints() - This method also takes no parameters and returns a static NodeList. The NodeList consists of insertion points in the destination insertion points of the context object. Given that the list is static, I suspect this method would primarily be used for debugging and inspection purposes.

Element.shadowRoot - This attribute either referes to the youngest ShadowRoot object (read only) if the node happens to be a shadow host. If not, it is null.

ShadowRoot - This is the object type of any shadow root which is returned by `Element.createShadowRoot(). A ShadowRoot object inherits from DocumentFragment.

The ShadowRoot type has a list of methods and attributes, several of which are not new, and are the usual DOM traversal and selection methods (getElementsBy*). We will cover the new ones and any that are of particular value when working shadow dom.

ShadowRoot.host - This attribute is a reference to its shadow host node.

ShadowRoot.olderShadowRoot - This attribute is a reference to any previously defined ShadowRoot on the shadow host node or null if none exists.

HTMLContentElement <content> - This node type and tag inherits from HTMLElement and represents a content insertion point. If the tag doesn’t satisfy the conditions of a content insertion point it falls back to a HTMLUnknownElement for rendering purposes.

HTMLContentElement.getDistributedNodes() - This method takes no arguments and either returns a static node list including anything transposed from the shadow host element, or an empty node list. This would likely be used primarily for inspection and debugging.

HTMLShadowElement <shadow> - Is exactly the same interface as HTMLContentElement except that it describes shadow insertion point instead.

Events and Shadow DOM

When you consider that shadow DOMs are distinct node trees, the standard browser event model will require some modification to handle user and browser event targets that happen to originate inside of a shadow DOM. In some cases depending on event type, an event will not cross the shadow boundary. In other cases, the event will be “retargeted” to appear to come from the shadow host element. The event “retargeting” algorithm described in specification proposal is quite detailed and complex considering that an event could originate inside several levels of shadow DOM. Given the complexity of the algorithm and the fluidity of the draft proposal, it doesn’t make sense to try to distill it here. For now, we shall just list the events (mostly “window” events) that are halted at the shadow root.

- abort

- error

- select

- change

- load

- reset

- resize

- scroll

- selectstart

CSS and Shadow DOM Encapsulation

As mentioned earlier, provisions are being made to include CSS selectors that will work with shadow DOM encapsulation. By default, CSS styling does not cross a shadow DOM boundary in either direction. There are W3C proposals on the table for selectors to cross the shadow boundary in controlled fashion designed to prevent inadvertent CSS bleeding. A couple terms, light DOM and dark DOM are used to help differentiate the actions these selectors allow. Light DOM refers to any DOM areas not under shadow roots, and dark DOM are any areas under shadow roots. These specs are actually in a section (3) of a different W3C draft proposal concerning CSS scoping within documents.

http://www.w3.org/TR/css-scoping-1/#shadow-dom

The specification is even less mature and developed than the others related to Web Components, so everything discussed is highly subject to change. At a high level CSS scoping refers to the ability apply styling to a sub-tree within a document using some sort of scoping selector or rule that has a very high level of specificity similar to the “@” rules for responsive things like device width.

What is currently being discussed are pseudo elements matching <content> and <shadow> tags, and a pseudo class that will match the shadow host element from within the shadow DOM tree. Also being discussed is a “combinator” that will allow document or shadow host selectors to cross all levels of shadow DOM to match elements. The current names are:

:host or :host( [selector] ) - a pseudo class that would match the shadow host element always or conditionally from a CSS rule located within the shadow DOM. This pseudo class allows rules to cross from the dark to the light DOM. The use case is when a UI component needs to provide its host node with styling such as for a theme or in response to user interaction like mouse-overs.

:host-context( [selector] ) - a pseudo class that may match a node anywhere in the shadow host’s context. For example, if the CSS is located in the shadow DOM of a UI component one level down in the document, this CSS could reach any node in the document.

Hopefully this one never sees the light of day in browser CSS standards! It is akin to JavaScript that pollutes the global context, and it violates the spirit of component encapsulation. The use case being posited that page authors may choose to “opt-in” to styles provided by the component is extremely weak. What is highly likely to happen is the same “path of least resistance” rushed developement where off-shore developers mis-use the pseudo class to quickly produce the required visual effect. Debugging and removing this crap later would be nothing short of nightmarish for the developer who ultimately must maintain the code.

::shadow - a pseudo element that allows CSS rules to cross from the light to the dark DOM. The ::shadow pseudo element could be used from the shadow host context to match the actual shadow root. This would allow a page author to style or override any styling in the shadow DOM of a component. A typical use-case would be to style a particular component by adding a shadow root selector:

.menu-item::shadow > a { color: green }

This presumably would override the link color of any MenuItem component.

::content - a pseudo element that presumably matches the parent element of any distributed nodes in a shadow tree. Recall that earlier we mentioned that any non-shadow content of a shadow host element that is transposed into the shadow tree with <content> retains its host-context styling. This would allow any CSS declared within the shadow DOM to match and style the transposed content. An analogous AngularJS situation would be something like the uicInclude directive we created in chapter 6 to replace parent scope with component scope for transcluded content.

The preceding pseudo classes and elements can only be used to cross a single shadow boundary such as from page context to component context or from container component context to “contained” component context. An example use case could be to theme any dropdown menu components inside of a menu-bar container component with CSS that belongs to the menu-bar. However, what if the menu-bar component also needed to provide theming for the menu-item components that are children of the dropdown components. None of the above selectors would work for that. So there is another selector (or more precisely a combinator) that takes care of situation where shadow DOMs are nested multiple levels.

/deep/ - a combinator (similar to “+” or “>”) that allows a rule to cross down all shadow boundaries no matter how deeply nested they are. We said above that ::shadow can only cross one level of shadow boundary, but you can still chain multiple ::shadow pseudo element selectors to cross multiple nested shadow boundaries.

menu-bar::shadow dropdown::shadow > a { ...

This is what you would do if you needed to select an element that is exactly two levels down such as from menu bar to menu item. If on the other hand, you needed to make sure all anchor links are green in every component on a page, then you can shorten your selector to:

/deep/ a { ... }

Once again, the proposal for these specs is in high flux, and you can expect names like ::content to be replaced with something less general by the time this CSS capability reaches a browser near you. The important takeaways at this point are the concepts not the names.

We will be covering some of the Web Components polyfills in the next chapter, but it is worth mentioning now that shadow DOM style encapsulation is one area where the polyfill shivs fall short. In browsers that do not yet support shadow DOM, CSS will bleed right through in both directions with the polyfills. Additionally, emulating the pseudo classes and elements whose names are still up in the air is expensive. The CSS must be parsed as text and the pseudo class replaced with a CSS emulation that does work.

There also appears to be varying levels of shadow DOM support entering production browser versions. For instance, as of mid-2014, Chrome 35 has shadow DOM API support, but not style encapsulation, whereas, Chrome Canary (37) does have style encapsulation. Opera has support. Mozilla is under development, and good old Microsoft has shadow DOM “under consideration”.

8.3 Adding some Shadow DOM to the Custom Element

<script>

// Instantiate what will be the custom element prototype

// object from an element prototype object

var MenuItemProto = Object.create(HTMLElement.prototype);

// add a parent component property

MenuItemProto.parentComponent = null;

// lifecycle callback API methods

MenuItemProto.created = function() {

// perform logic upon registration

this.parentComponent = this.getAttribute('parent');

// add some content

// this.innerHTML = "<a>add a label later</a>";

// instantiate a shadow root

var shadowRoot = this.createShadowRoot();

// move the <a> element into the "dark"

shadowRoot.innerHTML = "<a>add a label later</a>";

// attach the shadow DOM

this.appendChild( shadowRoot );

};

// the remaining custom element code is truncated for now

</script>

<menu-item parent="drop-down"></menu-item>

This is a minimalist example of creating, populating, and attaching shadow DOM to a custom element. The created or createdCallback (depending on final name) function is called when the instantiation process of a custom element is complete which makes this moment in the lifecycle ideal for instantiating and attaching any shadow roots needed for the component.

Rather than getting into a bunch of programmatic DOM creation for the sake of more indepth shadow DOM API examples, we will defer until the next section where we cover the <template> tag. <template> tags are the ideal location to stick all the HTML, CSS, and JavaScript that we would want to encapsulate as shadow DOM in our web component definition.

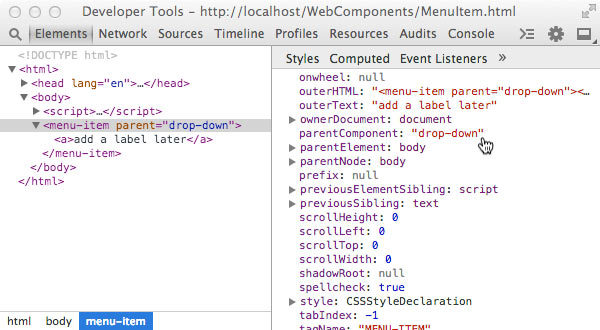

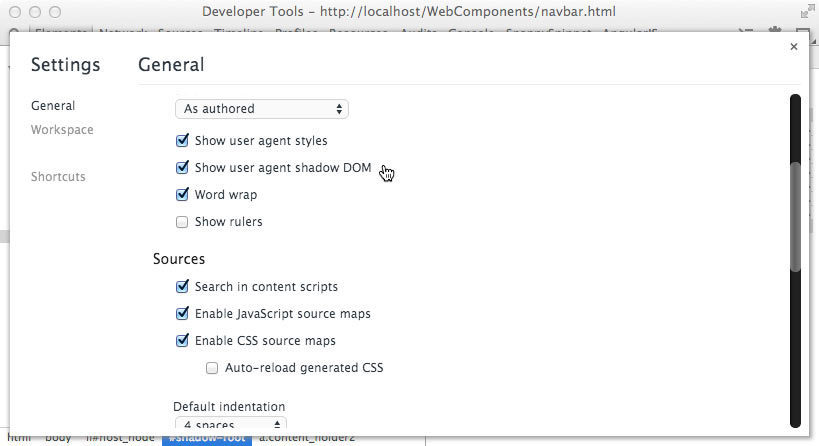

Shadow DOM Inspection and Debugging

As of Chrome 35, the developer tools settings have a switch to turn on shadow DOM inspection under General -> Elements. This will allow you to descend into any shadow root elements, but the view is the logical DOM, not the composed (rendered) DOM.

If you check this box, you can inspect shadow DOM

A view of the logical DOM (left) and a shadow DOM object (right)

What you see in dev tools likely won’t match what you see in the browser window. It’s a pretty good bet that by the time Web Components are used in production web development, the Chrome team will have added a way to inspect the composed DOM into dev tools. For the time being, Eric Bidelman of the Polymer team at Google has a shadow DOM visualizer tool, based on d3.js, that can be accessed at:

http://html5-demos.appspot.com/static/shadowdom-visualizer/index.html

It’s helpful for resolving content insertion points in the logical DOM for a single shadow host element, so you can get a feel for the basic behavior for learning purposes

Using the <template> Tag

The <template> tag is already an established W3C standard. It is meant to replace <script> tag overloading for holding inert DOM fragments meant for reuse. The only reason it has not already replaced <script> tag overloading in JavaScript frameworks is because, surprise, surprise, Internet Explorer has not implemented it. As of mid-2014, its status for inclusion in Internet Explorer is “under consideration”. This means we’ll see it in IE 13 at the earliest. So that is the reality check. We will pretend that IE does not exist for the remainder of this section.

http://www.w3.org/TR/html5/scripting-1.html#the-template-element

Advantages and Disadvantages

Today, if we want to pre-cache an AngularJS template for reuse, we overload a script tag with the contents as the template with the initial page load:

<script type="text/ng-template">

<!-- HTML structure and AngularJS expressions as STRING content -->

</script>

The advantage of this is that the contents are inert. If the type attribute value is unknown, nothing is parsed or executed. Images don’t download; scripts don’t run; nothing renders, and so on. However, disadvantages include poor performance since a string must be parsed into an innerHTML object, XSS vulnerability, and hackishness since this is not the intended use of a <script> tag. In AngularJS 1.2 string sanitizing is turned on by default to prevent junior developers from inadvertently allowing an XSS attack vector.

The contents of <template> tags are not strings. They are actual document fragment objects parsed natively by the browser and ready for use on load. However, the contents are just as inert as overloaded script tags until activated for use by the page author or component developer. The “inertness” is due to the fact that the ownerDocument property is a transiently created document object just for the template, not the document object that is rendered in the window. Similar to shadow DOM, you cannot use DOM traversal methods to descend into <template> contents.

The primary advantages of <template> tags are appropriate semantics, better declarativeness, less XSS issues, and better initial performance than parsing <script> tag content. The downside of using <template> tags include the obvious side effects in non-supported browsers, and lack of any template language features. Any data-binding, expression or token delimiters are still up to the developer or JavaScript framework. The same goes for the usual logic including loops and conditionals. For example, the core Polymer module supplies these capabilities on top of the <template> tag. There is also no pre-loading or pre-caching of assets within <template> tags. While template content may live in <template> tags instead of <script> tags for supported browsers, client-side templating languages are not going away anytime soon. Unfortunately for non-supporting browsers, there is no way to create a full shiv or polyfill. The advantages are supplied by the native browser code, and cannot be replicated by JavaScript before the non-supporting browser parses and executes any content.

What will likely happen in the near future is that JavaScript frameworks will include using <template> tags as an option in addition to templating the traditional way. It will be up to the developer to understand when using each option is appropriate.

8.4 Activating <template> Content

<template id="tpl_tag">

<script>

// though inline, does not execute until DOM attached

var XXX = 0;

</script>

<style>

/* does not style anything until DOM attached

.content_holder{

color: purple;

}

.content_holder2{

color: orange;

}

</style>

<!-- does not attempt to load this image until DOM attached -->

<img src="http://imageserver.com/some_image.jpg"/>

<a class="content_holder">

<content select="#src_span"></content>

</a>

<a class="content_holder2">

<content select="#src_span2"></content>

</a>

</template>

<script>

// create a reference to the template

var template = document.querySelector( '#tpl_tag' );

// call importNode() on the .content property; true == deep

var clone = document.importNode( template.content, true );

// activate the content

// images download, styling happens, scripts run

document.appendChild( clone );

</script>

As you can see, activating template content is simple. The main concept to understand is that you are importing and cloning an existing node rather than assigning a string to innerHTML. The second parameter to .importNode() must be true to get the entire tree rather than just the root node of the template content.

<template> tags work great in combination with custom elements and shadow DOM for providing basic encapsulation tools for UI (web) components.

8.5 <template> Tag + Shadow DOM + Custom Element = Web Component!

<!doctype html>

<html>

<head>

<title>A Web Component</title>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<meta http-equiv="X-UA-Compatible"

content="IE=edge,chrome=1">

<style>

/* this styling will still apply even after

the node has been "redistributed" */

web-component div {

border: 2px blue dashed;

display: flex;

padding: 20px;

}

/* uncomment this new pseudo class to prevent FOUC

(flash of unstyled content) */

/* :unresolved {display: none;} */

</style>

</head>

<body>

<!-- this displays onload as an "unresolved element"

unless we uncomment the CSS rule above -->

<web-component>

<div>origin content</div>

</web-component>

<template id="web-component-tpl">

<style>

/* example of ::content pseudo element */

::content div {

/* this overrides the border property in page CSS */

border: 2px red solid;

}

/* this pseudo class styles the web-component element */

:host {

display: flex;

padding: 5px;

border: 2px orange solid;

overflow: hidden;

}

</style>

The origin content has been redistributed

into the web-component shadow DOM.

The blue dashed border should now be

solid red because the styling in the template

has been applied.

<!-- the new <content> tag where shadow host element

content will be "distributed" or transposed -->

<content></content>

<!-- template tag script is inert -->

<script>

// alert displays only after the template has been

// attached and activated

alert('I\'ve been upgraded!');

</script>

</template>

<script>

// create a Namespace for our Web Component constructors

// so we can check if they exist or instantiate them

// programatically

var WebCompNS = {};

// creates and registers a web-component

function createWebComponent (){

// if web-component is already registered,

// make this a no-op or errors will light up the

// console

if( WebCompNS.WC ) { return; }

// this is actually not necessary unless we are

// extending an existing element

var WebCompProto = Object.create(HTMLElement.prototype);

// the custom element createdCallback

// is the opportune time to create shadow root

// clone template content and attach to shadow

WebCompProto.createdCallback = function() {

// get a reference to the template

var tpl = document.querySelector( '#web-component-tpl' );

// create a deep clone of the DOM fragments

// notice the .content property

var clone = document.importNode( tpl.content, true );

// call the new Element.createShadowRoot() API method

var shadow = this.createShadowRoot();

// activate template content in the shadow DOM

shadow.appendChild(clone);

// set up any custom API logic here, now that everything

// is in the DOM and live

};

// document.registerElement(local_name, prototypeObj) API,

// register a "web-component" element with the document

// and add the returned constructor to a namespace module

// the second (prototype obj) arg is included for educational

// purposes.

WebCompNS.CE = document.registerElement('web-component', {

prototype: WebCompProto

});

// delete the button since we no longer need it

var button = document.getElementById('make_WC');

button.parentNode.removeChild(button);

}

</script><br><br>

<button id="make_WC" onclick="createWebComponent()">

Click to register to register a "web-component" custom element,

so I can be upgraded to a real web component!

</button>

<!-- concepts covered: basic custom element registration, <template>,

<content> tags, single shadow root/host/DOM, :unresolved,

:host pseudo classes, ::content pseudo element -->

<!-- concepts not covered: <shadow>, multiple shadow roots,

/deep/ combinator, element extensions -->

</body>

</html>

Above is a bare bones example of using template tags, and shadow DOM in combination with custom elements to create a nicely encapsulated web component. You can load the above into Chrome Canary and play around with it today (mid-2014). You can probably load the above in Internet Explorer sometime in 2017, and it will work there too! It illustrates most of the important CSS and DOM APIs.

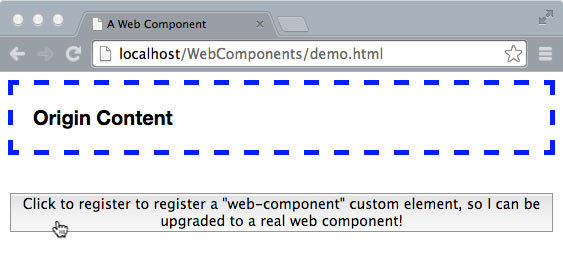

Screen grab of code listing 8.5 on browser load.

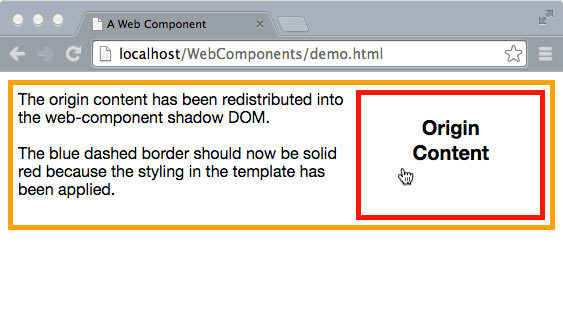

Screen grab after instantiating the web component including content redistribution and application of template styles to the content node.

The portion of code contained in the <template> tag, could also be wrapped in an overloaded <script> tag if that is preferable for some reason. The only difference in the code would be to grab the <script> content as text, create an innerHTML object and assign the text content to it, and then append it to the shadow root.

The CustomElement.createdCallback(), can be used for much, much more than grabbing template content and creating shadow roots. We could grab attribute values as component API input. We could register event bindings or listeners on the shadow host, and even set up data-binding with Object.observer() when that is available in ES7. We could emit custom events to register with global services such as local storage or REST. The created callback plus any template script is where all of our custom web component behavior would live.

In this contrived example, we are clicking a button to run the code that creates and registers the custom element web component. There is a more practical option for packaging and running this code, which is in a separate HTML file that can be imported into the main document via another new W3C standard proposal called HTML imports. We will cover this in the next section, as well as, the rest of the new CSS and DOM APIs.

HTML Imports (Includes)

The final specification proposal of the group that comprises “web components” is HTML import. It is essentially the ability to use HTML “includes” on the client-side. It is similar, but not identical, to the sever-side template includes we’ve been doing for 20 years (remember SSIs?). It is also similar to the way we load other page resources on the client side such as scripts, CSS, images, fonts, videos, and so on. The difference is that an entire document with all the pieces can be loaded together, and it can be recursive. An HTML import document can, itself, have an import document. This makes HTML imports an ideal vehical for packaging and transporting web components and their dependencies to a browser since web components, by definition, include multiple resources. It also adds a nice option for keeping component code organizationally encapsulated.

The mechanism proposed is to add a new link type to the current HTML link tag.

<link rel="import" href="/components/demo.html">

http://www.w3.org/TR/html-imports/

During the parsing of an HTML document, when a browser encounters an import link tag, it will stop and try to load it. So imports are “blocking” by default, just like <script> tags. However, they would be able to be declared with the “async” attribute to make them non-blocking like script tags as well. Import link tags can also be generated by script and placed in the document to allow lazy loading. As with other resource loaders, import links have onload and onerror callbacks.

Security and Performance Considerations

The same-origin security restrictions as iframes apply for the obvious reasons. So importing HTML documents from a different domain would require CORS headers set up by the domain exporting the web component document. In most cases, this would likely be impractical unless both domains had some sort of pre-existing relationship. In the scenario where both domains are part of the same enterprise organization, this is very doable. However if the web components are exported by an unrelated, third party organization, it would likely make more sense just to prefetch and serve them from the same server (be sure to check the licensing first). Also, for best performance, it may make sense to prebundle the necessary imports as part of the initial download similar to the way we pre-cache AngularJS templates.

Since these are HTML documents, browser caching is available which should also be considered when developing the application architecture. An HTML import document will only be fetched once no matter how many link elements refer to it assuming browser caching is turned on. Apparently any scripts contained in an import are executed asynchronously (non-blocking) by default.

One scenario to avoid at all costs is the situation where rendering depends on a complex web component that itself imports web components as dependencies multiple levels deep! This would mean multiple network requests in sequence. An “asynchronous document loader” library would certainly be needed. Another option is to “flatten” them into a single import which is what the NPM module, vulcanize from the Polymer team, does.

Differences from Server-side Includes

Using includes on the server-side, whether PHP, JSP, or ERB assembles the page which the client considers a single, logical document or DOM. This is not the case with HTML imports. Having HTML imports in a page means that there are multiple, logical documents or DOMs in the same window context. There is the primary DOM associated with the browser frame or window, and then there are the sub-documents.

This is where loading CSS, JavaScript, and HTML together can get confusing (and non-intuitive if you are used to server-side imports). So there are two things to understand which will help speed development and debugging.

- CSS and JavaScript from an HTML import executes in the window context the same as non-import CSS and JavaScript.

- The HTML from an HTML import is initially in a separate logical document (and is not rendered, similar to template HTML). Accessing and using it from the master document requires obtaining a specific reference to that HTML imports document object

Number two can be a bit jarring since includes on the server-side which we are most used to are already inlined. The major implication to these rules are that any JavaScript that access the included HTML will not work the same way if the HTML include is served as a stand-alone page. For example, to access a <template id=”web-component-tpl”> template in the imported document we would do something like the following to access the template and bring it into the browser context:

var doc = document.querySelector( 'link[rel="import"]' );

if(doc){

var template = doc.querySelector( '#web-component-tpl' );

}

This holds true for script whether it runs from the root document or from the import document. With web components it will be typical to package the template and script for the custom element together, so it is most likely that the above logic would execute from the component document.

However, consider the scenario in which we want to optimize the initial download of a landing page by limiting rendering dependencies on subsequent downloads. What we do is inline the content on the server-side, so it is immediately available when the initial document loads. If the component JavaScript tries the above when inlined it will fail.

Fortunately, since “imported” JavaScript runs in the window context it can first check to see if the ownerDocument of the template is the same as the root document and then use the appropriate reference for accessing the HTML it needs. Specifically,

8.6 HTML Import Agnostic Template Locator Function

// locate a template based on ID selector

function locateTemplate(templateId){

var templateRef = null;

var importDoc = null;

// first check if template is in window.document

if(document.querySelector( templateId )){

templateRef = document.querySelector(templateId);

// then check inside an import doc if there is one

} else if ( document.querySelector('link[rel="import"]') ){

// the new ".import" property is the imported

// document root

importDoc = document.querySelector('link[rel="import"]').import;

templateRef = importDoc.querySelector(templateId);

}

// either returns the reference or null

return templateRef;

}

var tpl = locateTemplate('#web-component-tpl');

The above function can be used in the web component JavaScript to get a template reference regardless of whether the containing document is imported or inlined. This function could and should be extended to handle 1) multiple HTML imports in the same document, and 2) HTML imports nested multiple levels deep. Both of these scenarios are all but guaranteed. However, this specification is still far from maturity, so hopefully the HTML import API will add better search capability by the time it becomes a standard.

A more general purpose way to check from which document a script is running is with the following comparison:

document.currentScript.ownerDocument === window.document

The above evaluates to true if not imported and false if imported.

Some JavaScript Friends of Web Components

We have covered the three W3C standards proposals, plus one current standard, that comprise what’s being called Web Components, templates, custom elements, shadow DOM, and HTML imports. There was one more called “decorators”, but that mysteriously disappeared.

In this section we will take a look at some new JavaScript features on the horizon that aren’t officially part of “Web Components” but will play a major supporting role to web component architecture in the areas of encapsulation, modularity, data-binding, typing, type extensions, scoping, and performance. The net effect of these JavaScript upgrades will be major improvement to the “quality” of the components we will be creating. Most of these features, while new to JavaScript, have been around for a couple decades in other programming languages, so we won’t be spending too much time explaining the nuts and bolt unless specific to browser or asynchronous programming.

Object.observe - No More Dirty Checking!

Object.observe(watchedObject) is an interface addition to the JavaScript Object API. This creates an object watcher (an intrinsic JavaScript object like scope or prototype) that will asynchronously execute callback functions upon any mutation of the “observed” object without affecting it directly. What this means in English is that for the first time in the history of JavaScript we can be notified about a change in an object of interest natively instead of us (meaning frameworks like AngularJS and Knockout) having to detect the change ourselves by comparing current property values to previous values every so often. This has big implications for data-binding between model and view (the VM in MVVM).

What’s awesome about this is that crappy data-binding performance and non-portable data wrappers will be a thing of the past! What sucks is that this feature will not be an official part of JavaScript until ECMA Script 7, and as of mid 2014, ECMA 5 is still the standard. Some browsers will undoubtedly implement this early including Chrome 36+, Opera, and Mozilla, and polyfills exist for the rest including the NPM module “observe-js”.

Observables are not actually part of W3C web components because they have nothing to do with web component architecture directly, and the standards committee is a separate organization, ECMA. But we are including some discussion about them because they have a big influence on the MVVM pattern which is an integral pattern in web component architecture. AngularJS 2.0 will use Object.observe for data-binding in browsers that support it with “dirty checking” as the fallback in version 2.0. According to testing conducted, Object.observe is 20 to 40 times faster on average. Likewise, other frameworks like Backbone.js and Ember that use object wrapper methods such as set(datum), get(datum), and delete(datum) to detect changes and fire callback methods will become much lighter.

http://wiki.ecmascript.org/doku.php?id=harmony:observe

This proposal actually has six JavaScript API methods. The logic is very similar to the way we do event binding now.

Proposed API

- Object.observe(watchedObject, callbackFn, acceptList) - The callback function automatically gets an array of notification objects (also called change records) with the following properties:

- type: type of change including “add”, “update”, “delete”, “reconfigure”, “setPrototype”, “preventExtensions”

- name: identifier of the mutated property

- object: a reference to the object with the mutated property

- oldValue: the value of the property prior to mutation

The type of changes to watch for can be paired down with the optional third parameter which is an array contaning a subset of the change types listed above. If this is not included, all types are watched.

- Object.unobserve(watchedObject, callbackFn) - Used to unregister a watch function on an object. The callback must be a named function that matches the one set with Object.observe. Similar to unbinding event handlers, this is used for cleanup to prevent memory leaks.

- Array.observe(watchedArray, callbackFn) - Same as Object.observe but has notification properties and change types related specifically to arrays including:

- type: type of array action including as splice, push, pop, shift, unshift

- index: location of change

- removed: and array of any items removed

- addedCount: count (number) of any items added to the array

- Array.unobserve(watchedArray, callbackFn) - This is identical to Object.unobserve

- Object.deliverChangeRecords(callback) - Notifications are delivered asynchronously by default so as not to interfere with the actual “change” sequence. Since a notification is placed at the bottom of the call stack, all the code surrounding the mutation will execute first, and there is no guarantee when exactly the notification will arrive. If a notification must be delivered at some specific point in the execution queue because it is a dependency for some logic, this method may be used to deliver any notifications synchronously.

- Object.getNotifier(O) - This method returns the notifier object of a watched object that can be used to define a custom notifier. It can be used along with Object.defineProperty() to define a set method that includes retrieving the notifier object and adding a custom notification object to its notify() method other than the default above.

8.7 An Example of Basic Object.observe() Usage

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head lang="en">

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<title>Object Observe Example</title>

<style>

body{font-family: arial, sans-serif;}

div {

padding: 10px;

margin: 20px;

border: 2px solid blue;

}

#output {

color: red;;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<div>

<label>Data object value: </label>

<span id="output">initial value</span>

</div>

<div>

<label>Input a new value: </label>

<input

type="text"

name="input"

id="input"

value=""

placeholder="new value">

</div>

<script>

// the data object to be "observed"

var dataObject = {

textValue: 'initial value'

};

// user input

var inputElem = document.querySelector('#input');

// this element's textValue node will be "data bound"

// to the dataObject.textValue

var outputElem = document.querySelector('#output');

// the keyup event handler

// where the user can mutate the dataObject

function mutator(){

// update the data object with user input

dataObject.textValue = inputElem.value;

}

// the mutation event handler

// where the UI will reflect the data object value

function watcher(mutations){

// change objects are delivered in an array

mutations.forEach(function(changeObj){

// the is the actual data binding

outputElem.textContent = dataObject.textValue;

// log some useful change object output

console.log('mutated property: ' + changeObj.name);

console.log('mutation type: ' + changeObj.type);

console.log('new value: ' + changeObj.object[changeObj.name]);

});

}

// set a keyup listener for user input

// this is similar to AngularJS input bindings

inputElem.addEventListener('keyup', mutator, false);

// set a mutation listener for the data object

// notice how similar this is to setting event listeners

Object.observe(dataObject, watcher);

</script>

</body>

</html>

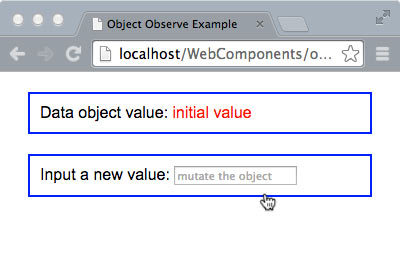

The Object.observe() example upon load

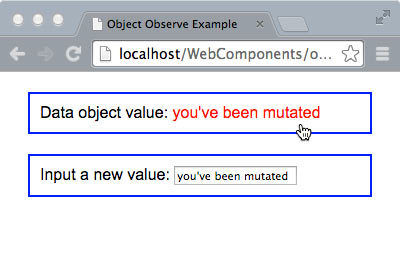

After the user has changed the data object value.

This example demonstrates a very basic usage of Object.observe(). One data property is bound to one UI element via the interaction of an event handler with a mutation observer. In real life an event handler alone is sufficient for the functionality in this example.

The actual value of Object.observe are situations where data properties are mutated either indirectly from user events or directly from data updates on the server, especially for real-time connections. There will no longer be a need for comparing data values upon events to figure out what might have changed, and there will no longer be a need for data wrapper objects such as Backbone.model to fire change events.

That said, in practice there will be a lot of boiler plate involved in creating custom watcher and notifiers. So it is likely that this API will be abstracted into a data-binding libraries and frameworks or utilized be existing frameworks for significantly better UI performance. This addition to JavaScript will allow web components to be quite a bit more user responsive, less bulky codewise, and better enabled for real-time data updates.

New ES6 Features Coming Soon

Object mutation observers are still a ways off, but some other great updates to JavaScript that enhance UI component code will be here a lot sooner, if not already. In fact, ES6 includes a number of enhancements that will help silence those high-horse computer scientists who look down on JavaScript as not being a real programming language. Features include syntax and library additions such as arrow functions, destructuring, default parameter values, block scope, symbols, weak maps, and constants. Support is still spotty among major browsers, especially for the features listed below that are of most use for component development. Firefox has implemented the most features followed by Chrome. You can probably guess who supports the least number of features. A nice grid showing ES6 support across browers can be found at:

http://kangax.github.io/compat-table/es6/

Our coverage is merely a quick summery of these JavaScript features and how they benefit UI component architecture. You are encouraged to gather more information about them from the plethora of great examples on the web. Plus, you are probably already familiar with and using many of these features via a library or framework.

Modules and Module Loaders

Modules and imports are a functionality that is a standard feature of almost all other languages, and has been sorely missing from JavaScript. Today we use AMD (asynchronous module definitions) via libraries such as Require.js on the client-side. Most of these handle loading as well. CJS (CommonJS) is primarily used server-side, especially in Node.js.

These libraries would be obsoleted by three new JavaScript keywords:

- module - would precede a code block scoped to the module definition.

- export - will be used within module declaration to expose that module’s API functionality

- import - like the name says, will be for importing whole modules or specific functionality from modules into the current scope

Modules will be loadable with the new Loader library function. You will be able to load modules from local and remote locations, and you will be about to load them asynchronously if desired. Properties and methods defined using var within a module definition will be scoped locally and must be explicitly exported for use by consumers using export. For the most part, this syntax will obsolete the current pattern of wrapping module definitions inside self-executing-anonymous-functions.

Just like shadow DOM with HTML, ES6 modules will help provide solid boundaries and encapsulation for web component code. This feature will likely take longer to be implemented across all major browser given that in mid-2014 the syntax is still under discussion. Regardless, it will be one of the most useful JavaScript upgrades to support UI component architecture.

EXAMPLE??

Promises

Promises are another well known pattern, supported by many JavaScript libraries, that will finally make its way into JavaScript itself. Promises provide a lot of support for handling asynchronous events such as lazy loading or removing a UI component and the logic that must be executed in response to such events without an explosion of callback spaghetti. The addition to native JavaScript allows promise support removal from libraries lightening them up for better performance. The Promise API is currently available in Firefox and Chrome.

Class Syntax

Though JavaScript is a functional prototyped language, many experienced server language programmers have failed to embrace this paradigm. This can be reflected by the many web developer job posting that include “object oriented JavaScript” in the list of requirements.

To help placate this refusal to embrace functional programming, a minimal set of class syntax is being added. It’s primarily syntactic sugar on top of JavaScript’s prototypal foundation, and will include a minimal set of keywords and built-in methods.

You will be able to use the keyword “class” to define a code block that may include a “constructor” function. As part of the class statement, you will also be able to use the keyword “extends” to subclass an existing class. Accordingly, within the constructor function, you can reference the constructor for the super-class using the “super” keyword. Just like Java, constructors are assumed as part of a class definition. If you fail to provide one explicitly, one will be created for you.

The primary benefit of class syntax to UI component architecture will be a minor improvement in JavaScript code quality coming from developers who are junior, “offshore” contractors, or weekend dabblers who studied object-oriented programming in computer science class.

EXAMPLE??

Template Strings

Handling strings has always been a pain-in-the-ass in JavaScript. There has never been the notion of multi-line strings or variable tokens. The current string functionality in JavaScript was developed long before the notion of the single page application where we would need templates compiled and included in the DOM by the browser rather than from the server.

The “hacks” that have emerged to support maintaining template source code as HTML including Mustache.js and Handlebars.js are bulky, non-performant, and prone to XSS attacks since they all must use the evil “eval” at some point in the compilation process.

http://tc39wiki.calculist.org/es6/template-strings/

With the arrival of template strings to JavaScript, we can say goodbye to endless quotes and “+” operators when we wish to inline multi-line templates with our UI components. We will be able to enclose strings within back ticks ( multi-line string ), and we will be able to embed variable tokens using familiar ERB syntax ( Hello: ${name}! ).

Proxies

The proxy API will allow you to create objects that mimic or represent other objects. This is a rather abstract definition because there are many use-cases and applications for proxies. In fact, complete coverage for JavaScript proxies including cookbook examples could take up a full section of a book.

Some of the ways proxies can benefit UI component architecture include:

- Configuring component properties dynamically at runtime

- Representing remote objects. For example, a component could have a persistence proxy that represents the data object on a server.

- Mocking global or external objects for easier unit testing

Expect to see proxies used quite a bit with real-time, full duplex web applications. A proxy API implementation is currently available to play with in Firefox, and more information can be gleaned at:

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Global_Objects/Proxy

Google Traceur Compiler

If you are itching to start writing JavaScript code using ES6 syntax, Google’s Traceur compiler can be used to translate it into ES5 which all major bowsers understand.

https://github.com/google/traceur-compiler/wiki/GettingStarted

http://google.github.io/traceur-compiler/demo/repl.html

Before using this for any production projects make sure you are well aware of any ES6 syntax or APIs that are still not completely “standardized” or likely to be implemented by certain browsers. Using these features can result in code that is not maintainable or prone to breakage. Also understand that with any JavaScript abstraction, the resulting output can be strange or unintelligible, therefore, difficult to debug.

AngularJS 2.0 Roadmap and Future Proofing Code

Web components and ES6 will be fantastic for encapsulating logic, functionality, styling and presentation for reusable pieces of a user interface. However, we will still need essential non-UI services that operate in the global or application level scope to turn a group of web components into an application. While old school widget libraries will disappear, application frameworks that supply services for things like REST, persistence, routing, and other application level singletons are not going anywhere anytime soon.

Now that these DOM and JavaScript additions are on the horizon, some of the more popular and forward leaning JavaScript frameworks including AngularJS and Ember are looking to incorporate these capabilities as part of their roadmap. The plan for AngularJS 2.0, is to completely rewrite it using ES6 syntax for the source code. Whether or not it is transpiled to ES5 with Traceur for distribution will depend on the state of ES6 implementation across browsers when 2.0 is released.

Another major change will be with directive definitions. Currently, the directive definition API is a one-size-fits-all implementation no matter what the purpose of the directive is. For 2.0, the plan is to segment directives along the lines of current patterns of directive use. The current thinking is three categories of directive. Component directives will be build around shadow DOM encapsulation. Template directives will use the <template> tag in some way, and decorator directives will be for behavior augmentation only. Decorator directives will likely cover most of what comprises AngularJS 1.x core directive, and they will likely be declared only with element attributes.

One of the hottest marketing buzz words in the Internet business as of mid-2014 is “mobile first”, and AngularJS 2.x has jumped on that bandwagon just like Bootstrap 3.x. So expect to see things like touch and pointer events in the core. The complete set of design documents for 2.0 can be viewed on Google Drive at:

https://drive.google.com/?pli=1#folders/0B7Ovm8bUYiUDR29iSkEyMk5pVUk

Brad Green, the developer relations guy on the AngularJS team, has a blog post that summarizes the roadmap.

http://blog.angularjs.org/2014/03/angular-20.html

Writing Future Proof Components Today

There are no best practices or established patterns for writing future-proof UI components since the future is always a moving target. However, there are some suggestions for increasing the likelihood that major portions of code will not need to be rewritten.

The first suggestion is keeping the components you write today as encapsulated as possible- both as a whole and separately at the JavaScript and HTML/CSS level. In this manner eventually you will be able to drop the JavaScript in a module, and the HTML/CSS into template elements and strings. Everything that has been emphasized in the first 2/3 of this book directly applies.

The second suggestion is to keep up to date with the specifications process concerning Web Components and ES6/7. Also watch the progress of major browser, and framework implementations of these standards. Take time to do some programming in ES6 with Traceur, and with Web Components using Chrome Canary, and the WC frameworks that we shall introduce in the next chapter. By making this a habit, you will develop a feel for how you should be organizing your code for the pending technologies.

Summary

Web Components will change the foundation of web development, as the user interface for applications will be built entirely by assembling components. If you are old enough to remember and have done any desktop GUI programming using toolkits like Java’s Abstract Windowing Toolkit (AWT), then we are finally coming full circle in a way. In AWT you assembled GUIs out of library components rather than coding from scratch. Eventually we will do the same thing with Web Components.

In the next chapter we will visit the current set of frameworks and libraries build on top of Web Component specifications including Polymer from Google, and X-Tag/Brick from Mozilla.