Time, Change, & Possibilities

Time and Change are the Wonder Twins of existence. Change without time wouldn’t exist, as change depends on transitioning from an initial state (past) to a new state (future) over time (present). Time without change couldn’t be proven to exist at all.

Imagine looking at a picture representing all of existence. The contents of the picture do not change. Prove, without referencing your own ability to perceive beyond the picture, that time is passing.

There’s an idiom that says, “The only constant is change.” That’s because time is constantly unfurling and everything is constantly changing, even only on a microscopic level.

The pre-Socratic philosopher, Heraclitus, is credited with saying, “You cannot step in the same river twice.” Another line is sometimes added, making the quote, “You cannot step in the same river twice for once you do, the river has changed and so have you.”

Sensory deprivation rooms are designed to minimize how much change you are exposed to. No clocks. Same small room. No sunrise or sunset. And, if you spend enough time in one, you could go insane. Of course, without change, you could not go insane. Or, move. Or, breathe. And, same is true if there was no time. So, at least we have that going for us.

Simply put, you could not experience existence nor prove that existence exists without time and change.

Time

Time has been around since, well, the beginning of time. Whether you think the beginning was a deity snapping its fingers, the Big Bang, or something in-between, before the beginning of time there was nothing; or, at least nothing to experience and, arguably, no consciousness to experience it. This is typically referred to as a linear-view of time; there is a beginning, middle (execution), and end.

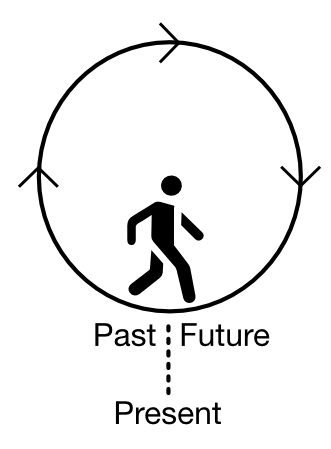

A linear-view of time is often compared to a circular- or cyclical-view; there is a beginning, middle (execution), and new beginning.

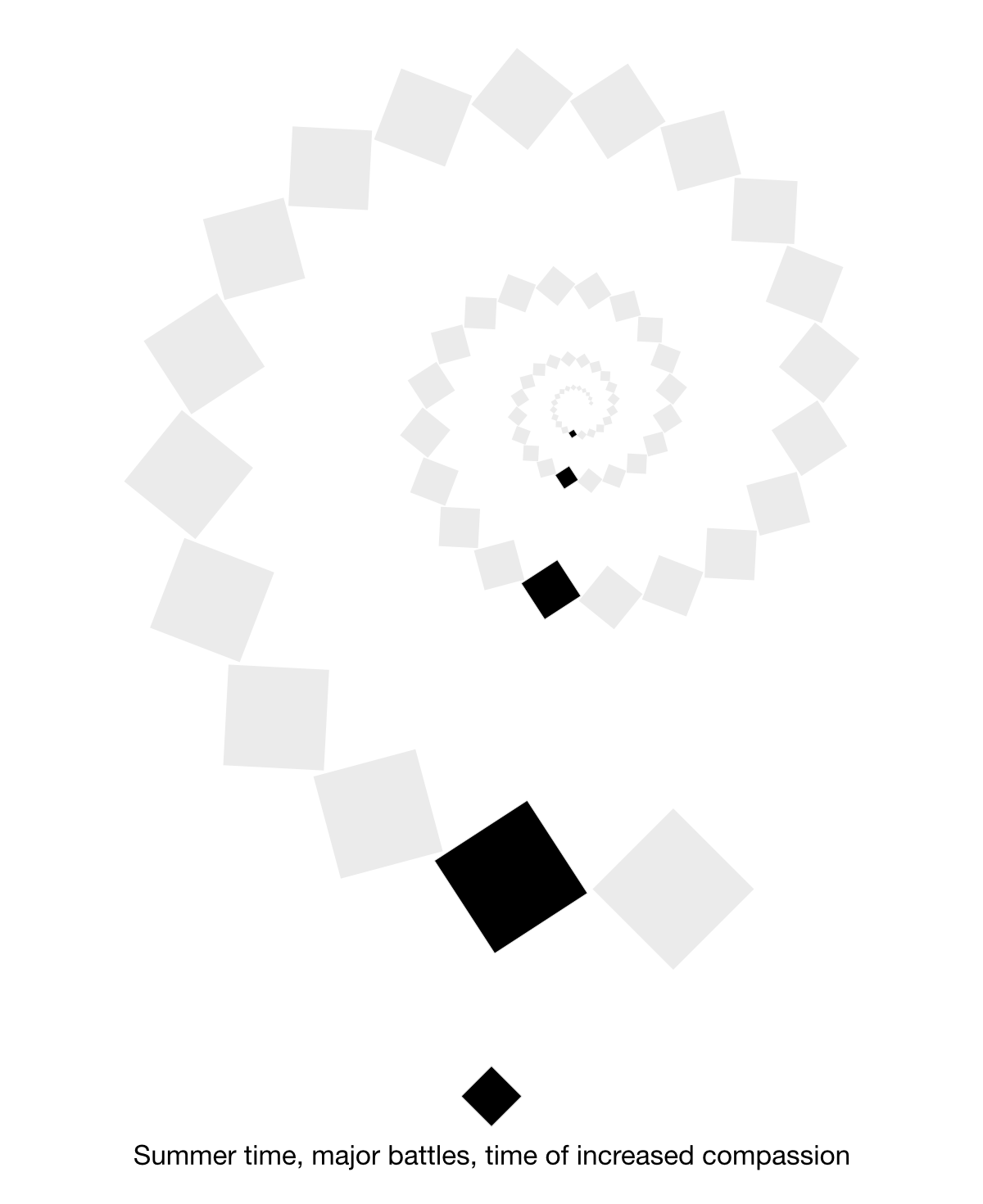

I’ve even heard of a spiral-view of time. A combination of linear and circular views. Imagine a spring standing upright. Time is the spring itself; however, if you take a vertical slice from the coil, events will not be much different within that slice, just the details.

It’s an attempt, if you will, to explain the concept of history repeating itself with a model of time that allows for repetition while simultaneously acknowledging that the War of 1812 was not the same as the Vietnam War.

Like all things, each view has its pleasures and pains.

A linear-view is helpful in capturing and reviewing history in discrete batches; however, viewing the past is often used as a way to try to control and predict the future, which is impossible. A circular view results in less emphasis on trying to control and predict the future and more emphasis on being in-sync with the cycles of time; however, you can become doomed to repeat the past. The spiral view is future-focused while viewing the past as unchangeable and the future as unknowable; however, this can lead to a fatalistic and hedonistic approach to life.

What view do you tend toward?

No matter which you lean toward, when it comes to your consciousness, to the best of our knowledge, there is a distinct beginning and end; a certain point before your birth and the moment of your death. This is your life time-box, otherwise known as lifetime, which is a limit, not a destination; meaning you could reach the end before your time has run out.

Whenever you give yourself an hour for a task, that’s a time-box. Just because you gave yourself an hour doesn’t mean you have to take an hour. The tension many feel with time is often grounded in pretty much the same fear. The fear of death or, more appropriately, a life not lived because none of us knows when our time-box will end.

Therefore, we spend time modifying diet, exercise, and sleep in the hope of getting more time compared to what we were given that we can spend later doing the things we want.

We want to spend time slower.

“Giving yourself an hour” is an interesting phrase because it takes time from a concept and tightly couples it to a method of measurement. One hour is one-twenty-fourth of a day. A day is one-seventh of a week. A week is roughly one-fourth of a month. A month is one-third of a season (or quarter). A season is one-fourth of a year. A year is one-nth of your lifetime.

Dividing things up this way makes time easier to grasp. (You might even divide lifetime by life-role; spouse, work, and so on.)

Time is neutral and democratic.

You can’t “buy more time.” You can’t “get time back” or “borrow time.” Your lifetime is an account. You have no idea what the balance is. You are constantly spending time, even while sleeping. And when the balance hits zero, that’s it. No overdraft protection. No loans to take out. No bailout of any kind (at least not yet).

The “good” and “bad” things you do may have little bearing on when you hit zero. People have lived to 100 years old while regularly smoking tobacco and drinking alcohol. Others have died around 50 while living a healthy lifestyle, literally while exercising. Others have died in their 30s after living a life of excess having just decided to live a healthier lifestyle.

Living life is a role playing game made of probabilities with few certainties.

I think writer and singer Henry Rollins said it best when he said, “No such thing as spare time, no such thing as free time, no such thing as down time. All you got is lifetime. Go.”

Time is not the enemy, stress is. Put another way, our response to the passage of time is what ultimately ages us.

How is it a 30 minute meeting can be exhausting, frustrating, and all you want to do is leave? However, you can go to a two-day retreat where you cried, felt emotionally raw, and all you wanted to do is stay?

We say things like, “This meeting is taking forever!” No it’s not. It just feels like it. Conversely, people say things like, “I lost track of time.” Of that there is no doubt.

The latter is what I mean when I tell people I have no concept of time. Even when I do make the time to check the time, I usually don’t freak out or become tense. Kind of an “Oh! Neat, that’s what time it is” feel.

Ultimately, time is:

- presumably infinite and personally finite,

- universally constant and personally unique,

- neutral and democratic.

Time doesn’t want you to lose. It’s just operating the way it knows how.

Past

The past is a nice place to visit, but I wouldn’t want to live there.

Josh Bruce, personal maxim

Many of us look to what we consider were our peak years and stay there or spend our lives trying to recapture them.

The high school football star who’s constantly trying to replicate that feeling in the present and future. The person who can’t bring themselves to form a new relationship because they’re still hung up on their previous one.

Still others look to the past as a way of gaining moral high ground in feuds: “I didn’t start it, you did.” Others look to the past as a way to control and predict the future; the concept of astrology is based on this.

Changing the past is impossible; we can only determine how to progress into the future, which is happening whether we want it to or not. Further, viewing past patterns may raise expectations, but it may not alter the probability of outcomes, which is the premise behind every weather forecasting joke ever. Finally, the farther into the past we look, the higher our probability of being wrong about what happened.

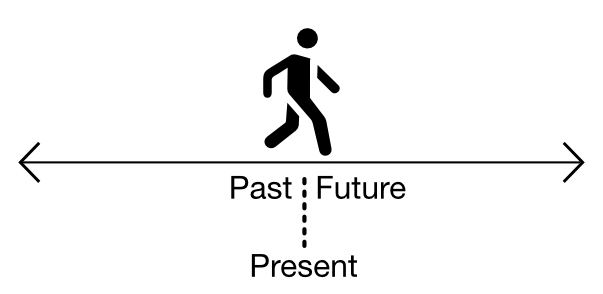

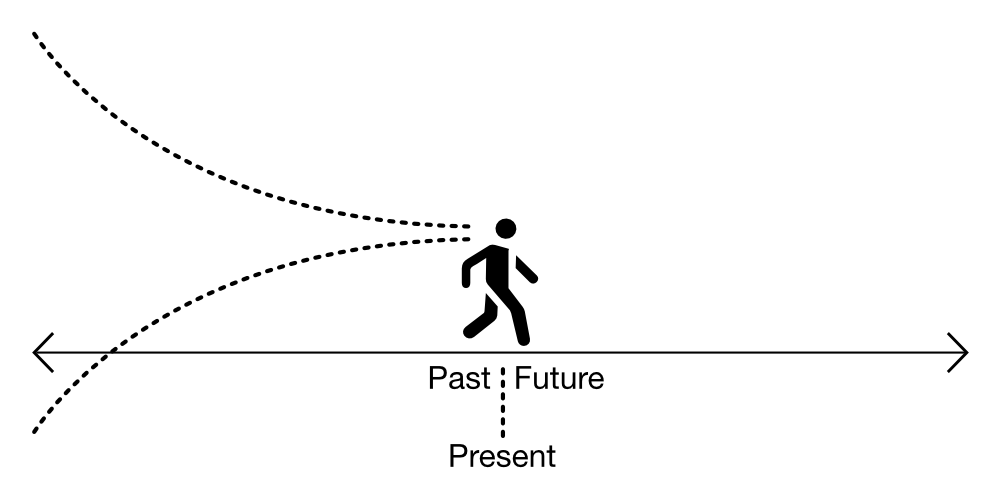

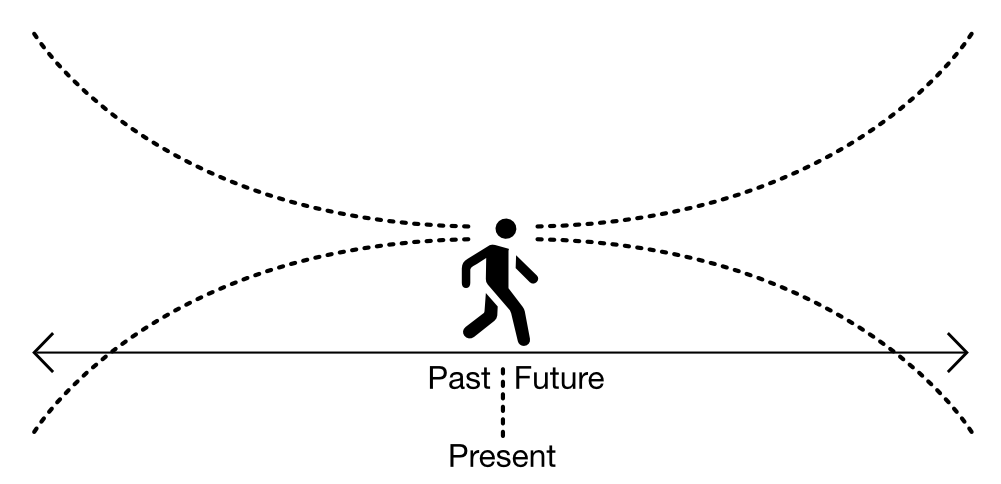

Imagine a horizontal line representing time. You stand in the middle. Spreading out behind you are two lines starting roughly from your head. They go from narrow to dramatically separated the farther away they go. The closer the lines, the more assured you can be your memory of a thing is correct. The farther apart the lines, the higher the probability your memory of the past will be incorrect.

Have you ever read something from someone, and it made you feel insulted or angry? Later you read it again or simply discover it was a misinterpretation of intent? Our brains are adept at molding our perception of the world and memory of it to match our expectations and emotions. No one has a monopoly on an objective view of history.

Present

The present is a fickle thing. Everything you just read or heard is in the past. And again. You’re in the present now. Nope, now.

You get the idea. The present is now. It is no longer than “that.” Only an experience can be longer than now.

The present is where reality is. The past is a memory. The future is filled with possibilities. Reality is right here and right now.

It’s not to say you shouldn’t come up for a breath now and again to survey the regions of the past and future, only that being in the moment offers solitude in a world that can be crazy and loud.

Future

The future is the past inverted and is based on speculation not memory.

Remember the horizontal line with the cone going from you to the beginning of your lifetime? This same cone, flipped horizontally, goes from you to the “end” of your lifetime. The closer the lines of the cone, the higher the probability you will be correct on what will happen. The farther apart the lines, the higher the probability you will be incorrect.

The uncertainty is what causes many of us to not appreciate change or deviation, which is seen as error. Our vision of the future must be the one that comes to fruition. Depending on the type of educational or household system you grew up in, your vision not coming to fruition could be seen as abject failure, which means you are also a failure. The fear of being wrong or failure has very strong emotions associated with it for many people.

Change

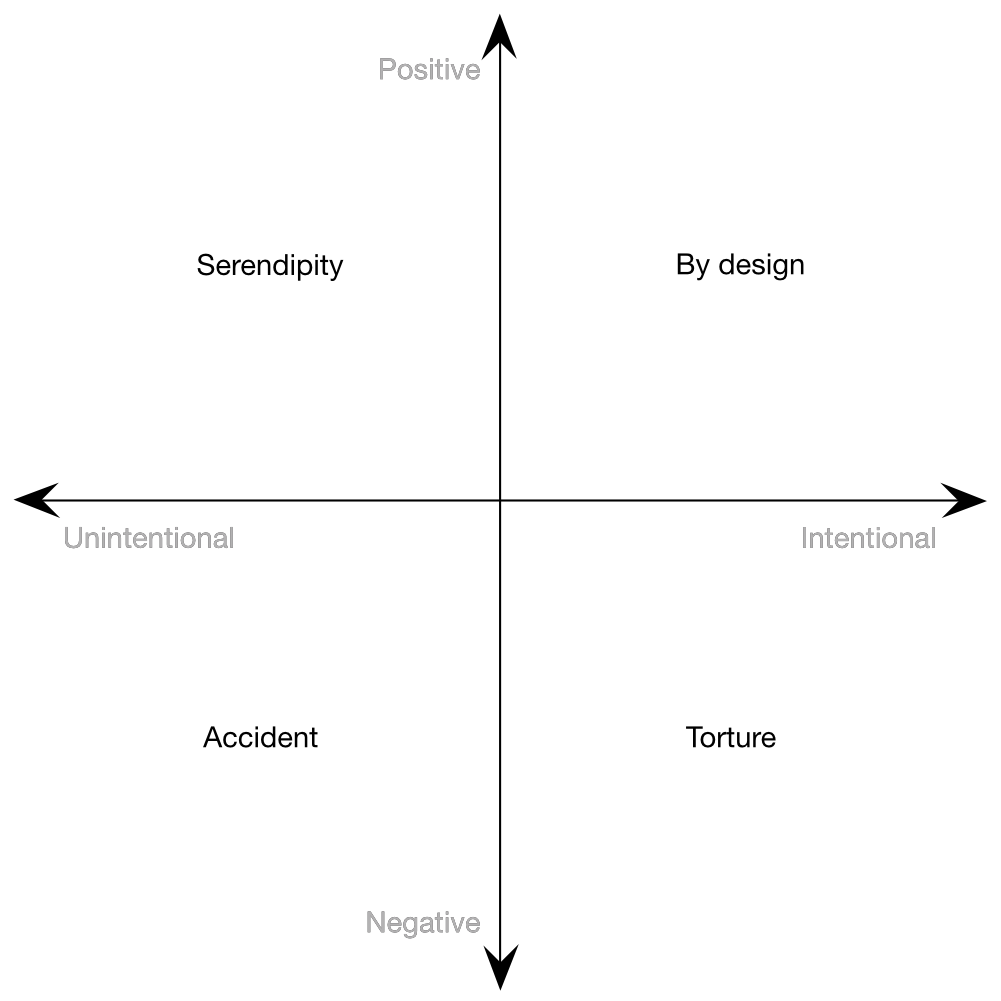

Imagine a chart. The X-axis goes from unintentional to intentional. The Y-axis goes from positive to negative.

Whenever a change happens, you can place a dot on that chart. The dot answers the questions:

- How did this change make me feel?

- How intentional was the agent of that change?

We have names we tend to call things that fall into the four quadrants:

- Unintentionally-positive is serendipity.

- Unintentionally-negative is an accident.

- Intentionally-positive is “by design.”

- Intentionally-negative is torture.

The chart measures in scales, not just buckets. As such, there are degrees of intentionality and grades of emotions. Further, the chart is informational, not judgmental; therefore, there is no “good” or “bad” place for something to be. Having said that, humans tend to favor intentionally-positive over other quadrants, including serendipity. The size and shape of elements placed in the chart can be used to indicate other things as well.

The size of a marker may indicate the forewarning given for a specific event like a hurricane or earthquake. The hurricane shape would most likely be larger than that of an earthquake. Hurricanes we usually see coming days, if not weeks, in advance. Earthquakes can happen in a matter of moments.

The shape placed on the chart may indicate the destructive or constructive nature of the event. A hurricane that never hits land might stay a triangle as it is not viewed as destructive to humans. A severe earthquake, on the other hand, might be an octagon, indicating its destructive force. A painter painting a portrait might be a circle illustrating a creative force.

Zones of Change

for each desired change, make the change easy (warning: this may be hard), then make the easy change

Kent Beck, Tweet from 2012

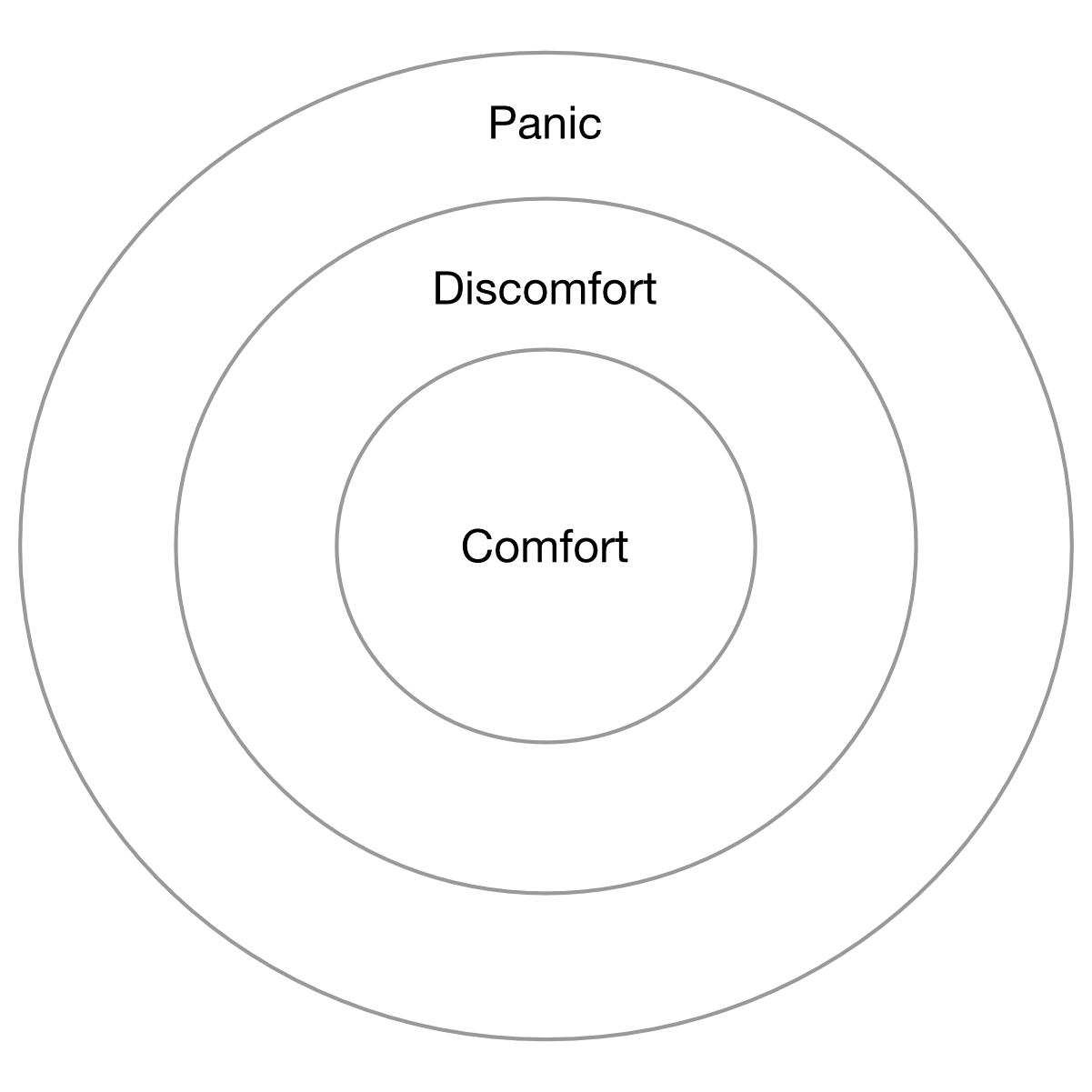

You’re walking in a forest. You pick up a stick. You have changed the stick. You bend the stick a little, no noises are made. You continue bending, it creaks and pops. You continue, suddenly it snaps in two.

You changed the stick, at least twice. Once when you picked it up. Twice when it stopped being a stick and became two sticks. And, really, every point you were interacting with the stick, but we’ll focus on major changes.

In the beginning, the stick was in its comfort zone. The comfort zone has little to no stress and feels safe. When you started bending the stick, it remained in its comfort zone. When the stick started creaking and popping it passed into the discomfort zone; stressful yet still safe. Finally, the stick hit the panic zone, filled with stress and danger. Eventually, the stick hit the end of the panic zone and split in half (violently rebounding to the comfort zone but not the same).

When changing things, it’s usually preferred that the panic zone be avoided. Forcing a rose open before it’s ready usually doesn’t end well for the rose or the one forcing it open. With exposure to different types of changes, the comfort zone tends to grow in size. Or, the object of change can be manipulated or prepared in some way (putting the stick in warm water would have softened it to bend farther before snapping).

Final doesn’t Exist

I had been working on a site with a client for about two years when he asked, “When’s it gonna be done?”

To which I replied, “It’s software development; it’s never done.”

“What do you mean?”

“Let’s try this. It’ll be finished when users don’t report defects, users don’t ask for new features, or y’all decide to replace it with something else; otherwise, someone will always be doing something to it. Beyond that, we were finished with the base requirements and migration six months ago, and users aren’t reporting bugs. So, I’ll be finished when you stop asking for things or stop paying me, whichever comes first. You’ll be finished when you move on to another project.”

With a laugh, the client said, “Ah! Gotcha.”

“Yeah,” I continued. “Once you build it or acquire it, you’re maintaining or improving it. Otherwise we’d all be running the first version of our operating systems, living in houses with thatch roofs, or everything around us would just be slowly falling apart” I finished, knowing this would probably be our last conversation.

I honestly think they were still using that system a decade later. Still not final.

Humans attach permanence to things marked “final,” “finished,” or “done.” Even things not marked that way can become viewed as unchanging because it’s been so long since a noticeable change has occurred or the expectation that things don’t change (people surprised a definition for a word in the same dictionary is different from one year to the next). Of course, if nothing is ever “done,” we wouldn’t feel like we accomplished anything.

That’s one reason endurance activities like marathons have some sort of milestone to gauge progress. Climbing a tall mountain might have basecamps every few miles. Without things like that we get lost in the monotony of putting one foot in front of the other. The monotony causes us to lose morale to continue. Or, you can flip it to be the thing driving you: “Yes! I’m one step closer.”

You often see this in meetings. People glancing at their watches, the clock on their computer, their phones, anything to get a feel for just how much longer they have to endure the monotony of this meeting. (“Twenty more minutes; I can make it!”) Many of us need those mile markers to drive us forward. To inspire us to press on. To give us even the slightest dopamine hit.

That’s one of the reasons possibility lists are so effective. Each item you mark off gives you a little dose of happiness.

Most changes, positive or negative, do not wait for you to be “ready.” When we see it as positive, we’re okay not being completely ready. What wrecks people is something negative happening they never thought would or were oblivious to.

It’s easier to prepare for the worst when the worst isn’t happening.

Possibilities

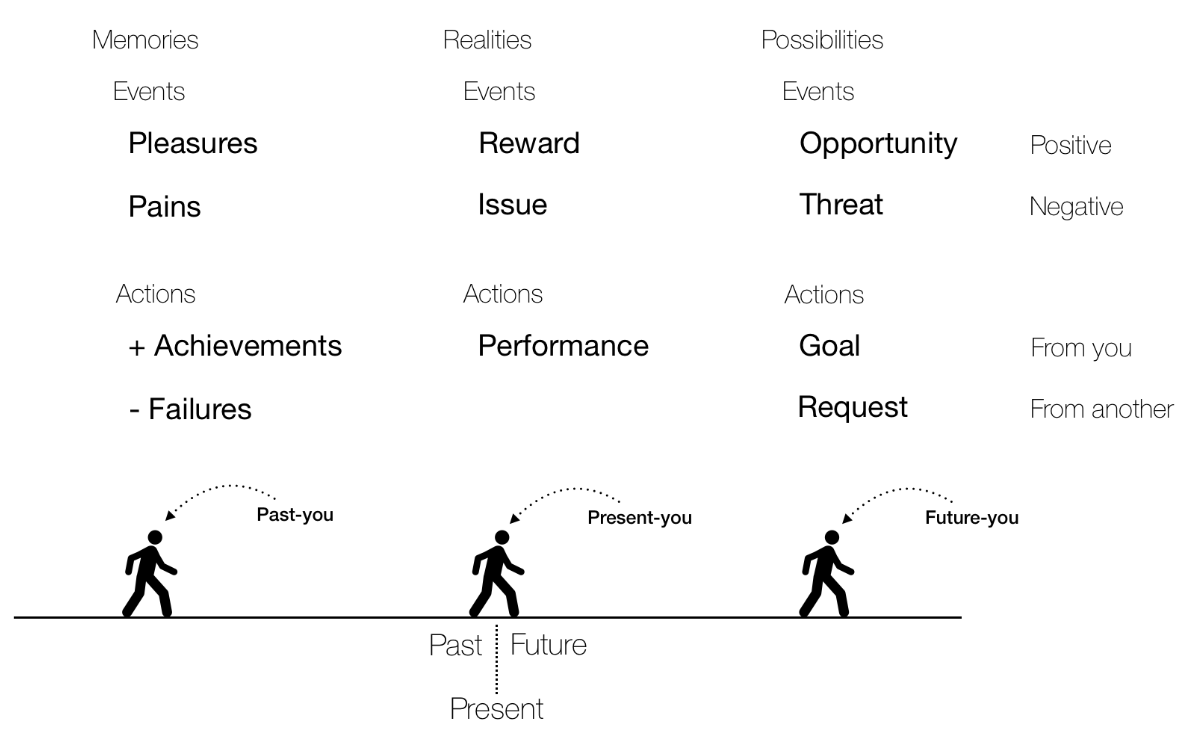

The combination of time and change is the opening to the realm of events and actions. Events and actions have future, present, and past types.

The definitions used here might be a bit different and are foundational to what we’re talking about.

- Possibilities

- are events or actions that could happen.

- Realities

- are events or actions that are happening.

- Memories

- are events or actions that have happened.

- Events

- are things outside of yourself, and usually outside your control, that could impact, are impacting, or have impacted your life large and small.

- Actions

- are things you do that could impact, are impacting, or have impacted the outside world large and small.

The aforementioned sub-types have two sub-types based on perceived positive and negative impact. Further, there are three variants based on time.

- Opportunities

- are possible future events believed to have a positive impact should they become reality.

- Threats (or Risks)

- are possible future events believed to have a negative impact should they become reality.

- Goals

- are possible future actions originating from yourself.

- Requests

- are possible future actions asked of you by someone or something else.

- Rewards

- are present events having a positive impact on your life. Not necessarily in return for you doing anything.

- Issues

- are present events having a negative impact on your life.

- Performances

- are a goal or request currently being executed.

- Pleasures

- are past events with a positive impact on your life.

- Pains

- are past events with a negative impact on your life.

- Achievements

- are past performances successfully executed.

- Failures

- are past performances not successfully executed.

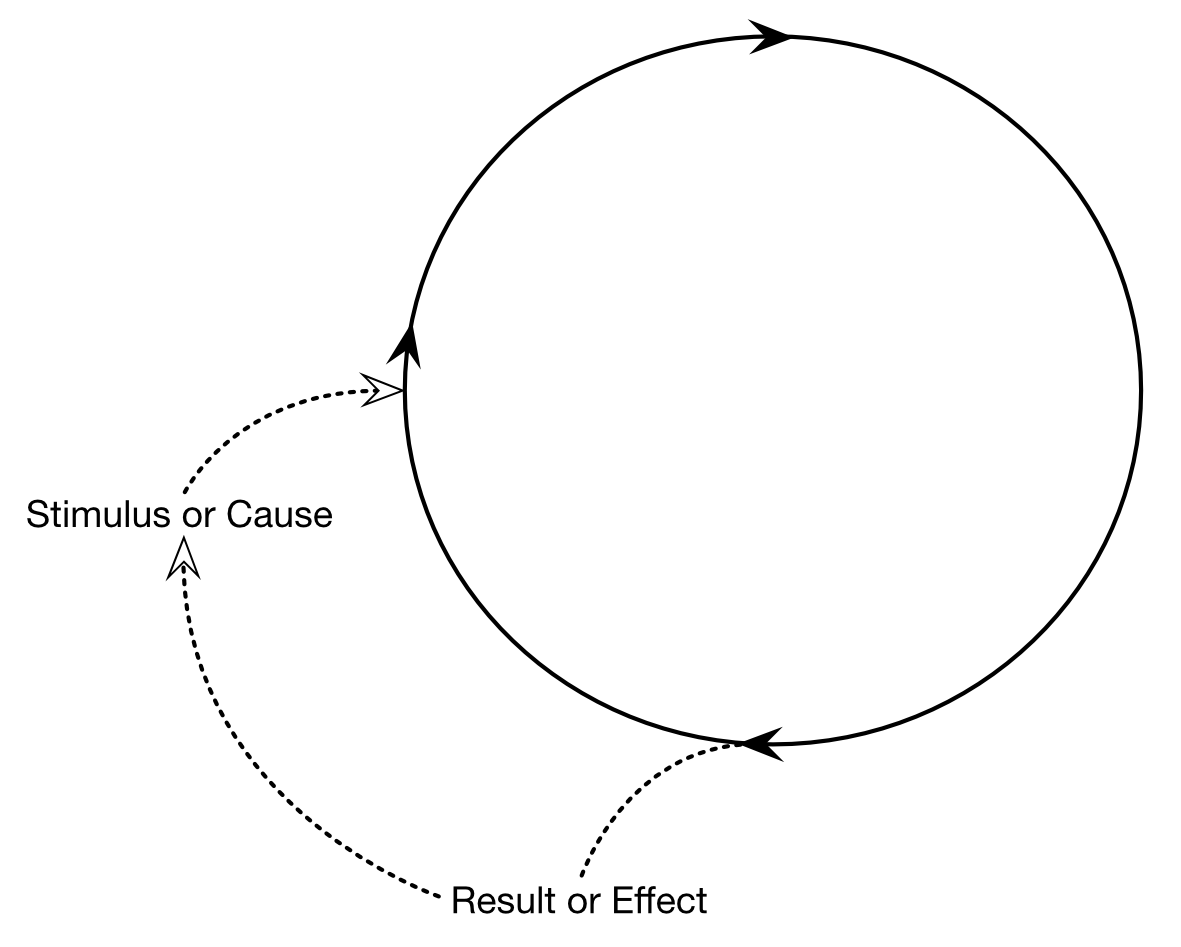

All possibilities have a probability of turning into a reality. All realities become memories. All three have a perceived or real impact on you. Each impact has a duration. How long will it affect you or the outside world. This is what we commonly refer to as cause and effect. A possibility becomes a reality (cause) that affects you and the outside world.

A cause sparks an event or action. The event or action has some type of result. That result may cause some other event or action to spark. This is a foundational model we’ll see a lot with varying degrees of complexity.

It’s important to note that these are not lifecycles. In other words, it is often perceived that threats can only become issues. While that is often the case, it is possible something perceived as having a future negative impact actually has a positive impact when it happens or over the long run.

You’re asleep in bed. You hear the door open and think it’s a burglar (threat). You head toward the door slowly, phone ready to call emergency services. A voice calls out, “Don’t worry, it’s just me.”

The “me” in question being your significant other (reward). As you come rushing into the kitchen, you slip and fall, hurting your elbow and dropping your phone, cracking the screen (pain).

The question that gets raised is: Was the previous example one experience or event, many experiences or events, or both? This brings us to the notion of the Action Loop, which is fractal-like in nature and seen to varying degrees throughout productivity literature.