Change

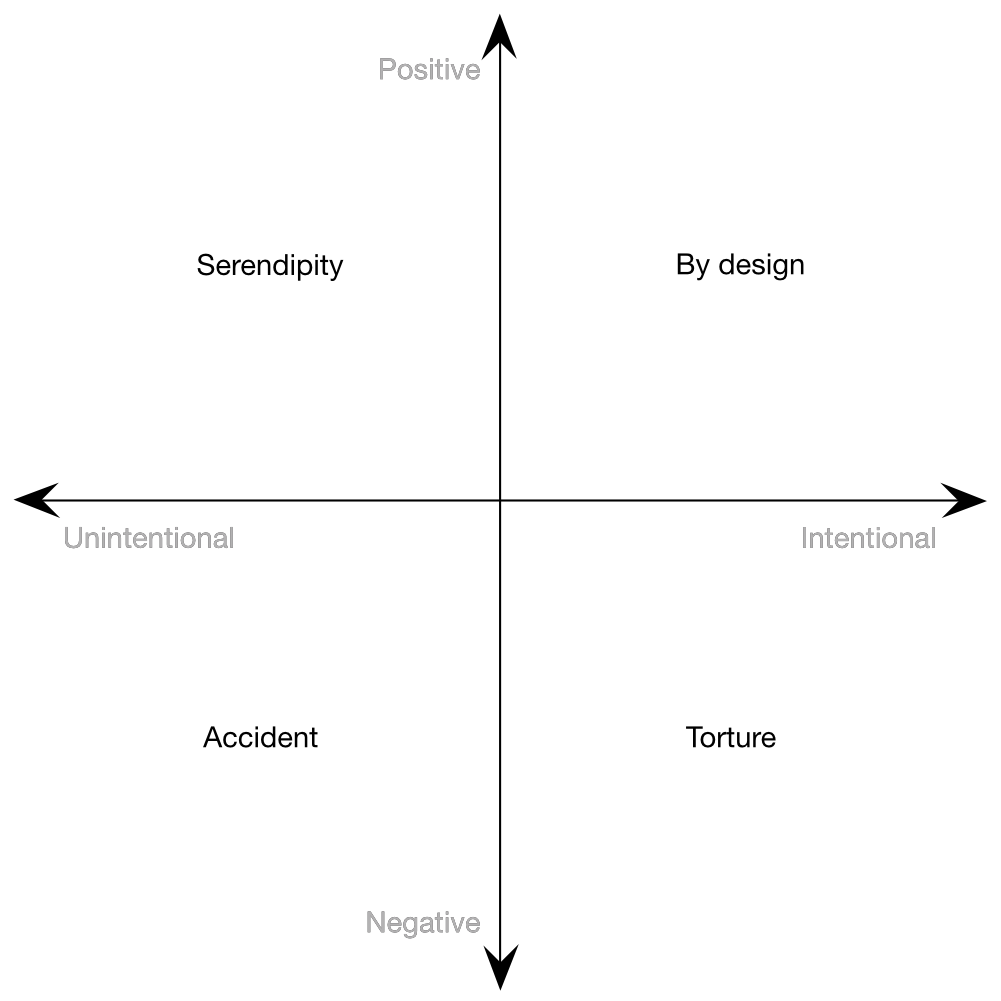

Imagine a chart. The X-axis goes from unintentional to intentional. The Y-axis goes from positive to negative.

Whenever a change happens, you can place a dot on that chart. The dot answers the questions:

- How did this change make me feel?

- How intentional was the agent of that change?

We have names we tend to call things that fall into the four quadrants:

- Unintentionally-positive is serendipity.

- Unintentionally-negative is an accident.

- Intentionally-positive is “by design.”

- Intentionally-negative is torture.

The chart measures in scales, not just buckets. As such, there are degrees of intentionality and grades of emotions. Further, the chart is informational, not judgmental; therefore, there is no “good” or “bad” place for something to be. Having said that, humans tend to favor intentionally-positive over other quadrants, including serendipity. The size and shape of elements placed in the chart can be used to indicate other things as well.

The size of a marker may indicate the forewarning given for a specific event like a hurricane or earthquake. The hurricane shape would most likely be larger than that of an earthquake. Hurricanes we usually see coming days, if not weeks, in advance. Earthquakes can happen in a matter of moments.

The shape placed on the chart may indicate the destructive or constructive nature of the event. A hurricane that never hits land might stay a triangle as it is not viewed as destructive to humans. A severe earthquake, on the other hand, might be an octagon, indicating its destructive force. A painter painting a portrait might be a circle illustrating a creative force.

Zones of Change

for each desired change, make the change easy (warning: this may be hard), then make the easy change

Kent Beck, Tweet from 2012

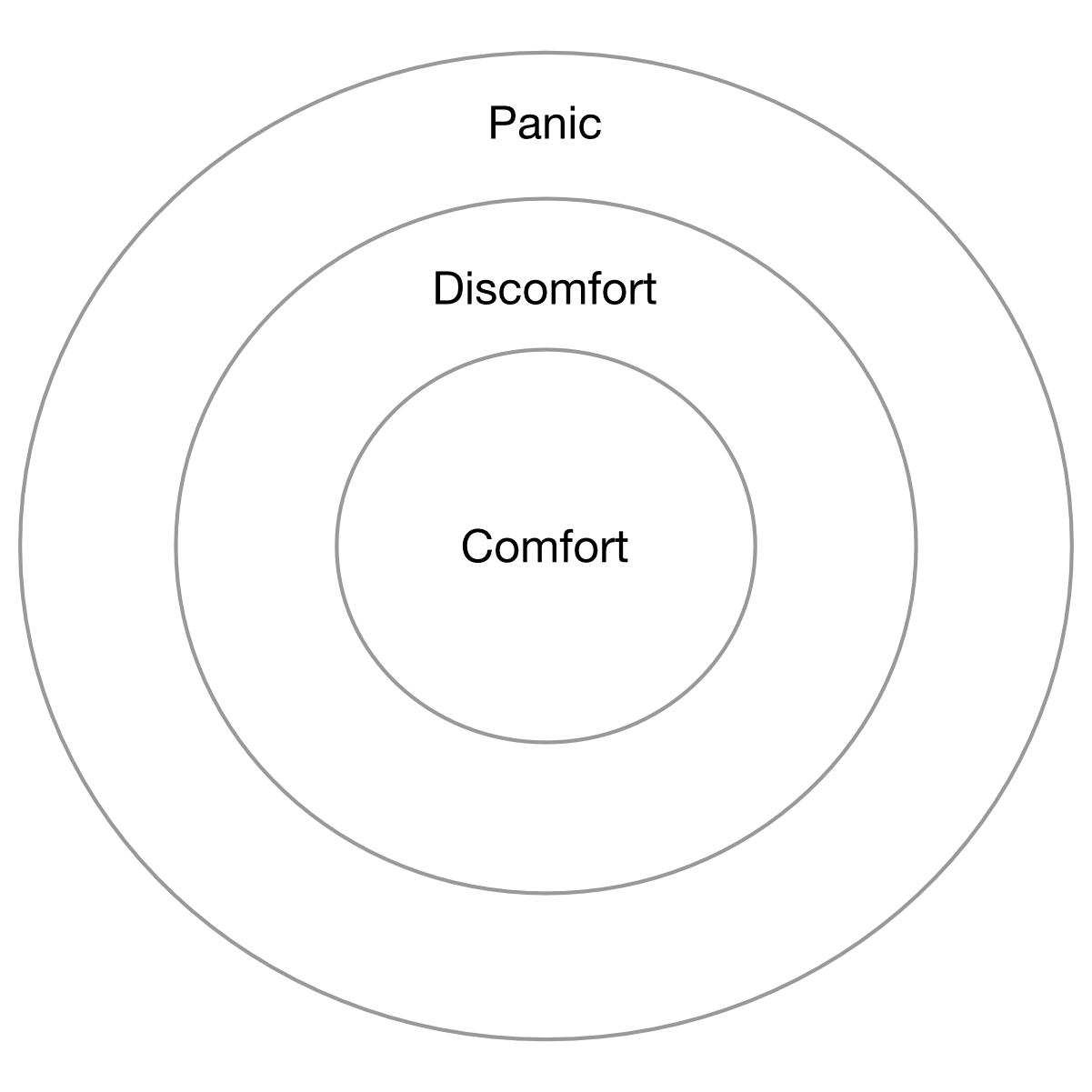

You’re walking in a forest. You pick up a stick. You have changed the stick. You bend the stick a little, no noises are made. You continue bending, it creaks and pops. You continue, suddenly it snaps in two.

You changed the stick, at least twice. Once when you picked it up. Twice when it stopped being a stick and became two sticks. And, really, every point you were interacting with the stick, but we’ll focus on major changes.

In the beginning, the stick was in its comfort zone. The comfort zone has little to no stress and feels safe. When you started bending the stick, it remained in its comfort zone. When the stick started creaking and popping it passed into the discomfort zone; stressful yet still safe. Finally, the stick hit the panic zone, filled with stress and danger. Eventually, the stick hit the end of the panic zone and split in half (violently rebounding to the comfort zone but not the same).

When changing things, it’s usually preferred that the panic zone be avoided. Forcing a rose open before it’s ready usually doesn’t end well for the rose or the one forcing it open. With exposure to different types of changes, the comfort zone tends to grow in size. Or, the object of change can be manipulated or prepared in some way (putting the stick in warm water would have softened it to bend farther before snapping).

Final doesn’t Exist

I had been working on a site with a client for about two years when he asked, “When’s it gonna be done?”

To which I replied, “It’s software development; it’s never done.”

“What do you mean?”

“Let’s try this. It’ll be finished when users don’t report defects, users don’t ask for new features, or y’all decide to replace it with something else; otherwise, someone will always be doing something to it. Beyond that, we were finished with the base requirements and migration six months ago, and users aren’t reporting bugs. So, I’ll be finished when you stop asking for things or stop paying me, whichever comes first. You’ll be finished when you move on to another project.”

With a laugh, the client said, “Ah! Gotcha.”

“Yeah,” I continued. “Once you build it or acquire it, you’re maintaining or improving it. Otherwise we’d all be running the first version of our operating systems, living in houses with thatch roofs, or everything around us would just be slowly falling apart” I finished, knowing this would probably be our last conversation.

I honestly think they were still using that system a decade later. Still not final.

Humans attach permanence to things marked “final,” “finished,” or “done.” Even things not marked that way can become viewed as unchanging because it’s been so long since a noticeable change has occurred or the expectation that things don’t change (people surprised a definition for a word in the same dictionary is different from one year to the next). Of course, if nothing is ever “done,” we wouldn’t feel like we accomplished anything.

That’s one reason endurance activities like marathons have some sort of milestone to gauge progress. Climbing a tall mountain might have basecamps every few miles. Without things like that we get lost in the monotony of putting one foot in front of the other. The monotony causes us to lose morale to continue. Or, you can flip it to be the thing driving you: “Yes! I’m one step closer.”

You often see this in meetings. People glancing at their watches, the clock on their computer, their phones, anything to get a feel for just how much longer they have to endure the monotony of this meeting. (“Twenty more minutes; I can make it!”) Many of us need those mile markers to drive us forward. To inspire us to press on. To give us even the slightest dopamine hit.

That’s one of the reasons possibility lists are so effective. Each item you mark off gives you a little dose of happiness.

Most changes, positive or negative, do not wait for you to be “ready.” When we see it as positive, we’re okay not being completely ready. What wrecks people is something negative happening they never thought would or were oblivious to.

It’s easier to prepare for the worst when the worst isn’t happening.