Introduction

I’m not usually a fan of introductions to books. However, given this book tries to be high on utility and pragmatism, having a more philosophical and emotional introduction seems to make sense.

My Confession

I’m the hardest working lazy person you’ll ever meet. I’m willing to work very hard so I don’t have to.

Josh Bruce, self-referential joke

We’re all sort of hardworking lazy people, mostly from our perception of work and literally how the human body functions. When I say “lazy,” I don’t mean I want to sit around and do nothing while zoning out on mindless television. Further, when I say “work,” I typically mean something I didn’t volunteer to do, aren’t driven to do, and feel pressured to get done. I have to work to stay focused. I have to work to care emotionally. I have to work to take one more step.

Everything else in my life is play.

Some people operate well in environments where they’re told to do work they don’t care about while being pressured to turn it around in 24 hours or less when 48 is more appropriate. They enjoy the adrenaline rush. The feeling of being a superhero for a day or the underdog overcoming insurmountable odds.

That’s not me.

That’s my confession.

Now for my obsession.

The passage of time. More specifically, my emotional response to the passage of time. More generally, the emotional response of others to the passage of time.

Randy Pausch once said, “Time is the only commodity that matters” and I agree. With that said, I have no concept of time.

Just to make sure that landed, I have no concept of time.

When I told a friend this he laughed. It is admittedly odd that the time-obsessed, hard-working, “lazy” person, has no concept of time.

One hour is one hour. That doesn’t describe time, that describes a measurement system for time. If you spend one hour in a meeting and one hour playing a game you enjoy, the time has not changed, only the context. More specifically, your perception and response to the context.

The “container” (setup and surroundings) for the meeting you attended was probably CRAP, which contributed to people becoming DRAB.

CRAP is a mnemonic I use to remember things we want to avoid when setting and maintaining a container for an interaction:

- Communication Barriers: static on phone lines, overuse of acronyms, interruptions, and so on.

- Rushed: “Quick! We should have a meeting on solving world hunger with 100 of the greatest minds on the planet, and we’ll do it in 30 minutes or less.”

- No Agenda: “Why are we here? What are we wanting to accomplish? How are we going to accomplish it? Who should be here and why?”

- Pointless: “We totally could have done this via text or email.”

DRAB is another mnemonic I use for what typically happens to (or the types of) people within a container, CRAP or not:

- Disengaged: “I would really rather be doing something else.” Note: They may also be really engaged in something else, just not the thing they’re in the room for.

- Resentful: “Oh, great, I get to go to another one of his (or her) meetings. Really getting tired of them; they’re always CRAP.”

- Annoyed, Angry, or Agitated: This could be tied to resentment if directed at the organizer but could also be between members of the group.

- Bored: “So, let me get this straight, you want me to sit here and watch you enter things on your computer while I wait for the moment you may, or may not, ask my opinion on something you can’t answer yourself? Guess this is another meeting where I count the threads on my shoelaces.”

Meanwhile, your game playing experience was the opposite. Conversation was flowing, you didn’t care how much time passed, you knew why you were there, and it had purpose. Not only that, but you were engaged in all that was going on around you, enjoying the company of others, and could not think of anything else you’d rather be doing.

The gameplay description is close to that of flow.

For me, I try to make every experience the gameplay experience and I work hard to keep it that way. If that sounds interesting and possibly appealing, then I hope to help shed some light on walking through life in a consistent, if not constant, state of meditation.

Humans

On Earth, humans are at the top of the food chain. Any one of our nearest neighbors in that chain could whoop us in a fair fight, but there we are. We’re not the biggest, strongest, fastest, or most adept at fighting. However, we’re one of the only animals able to easily adapt to almost any environment (or to adapt the environment to us) within a single lifetime…in other words, we would probably be extinct if not for a couple of things pertinent to this book.

Our ability to:

- fashion and improve tools;

- pass knowledge to future generations;

- form coalitions (work together toward a common purpose);

- envision the future in ways other animals cannot; and

- run excessively long distances without keeling over from exhaustion, lack of oxygen, or heat.

For example, someone in a family creates a stone axe made of flint. This person teaches their children how to do the same. Their children improve it and teach their children the improved way. The third generation continues to improve the methods. The family (coalition) as a whole becomes better equipped to forage for food and protect themselves; thus survive.

Language

Over my life, career, and researching this book I’ve noticed a common thread in what causes misunderstandings and suffering: Language.

High school is probably when I first really noticed. A friend once said, “He cheated on me.”

“Did he know the rules?” I asked.

“He was my boyfriend,” she replied, thinking that meant everything.

“Does he know what that means to you?” I asked.

“Why are you defending him?”

“I’m not. I’m pointing out that you can’t cheat if you don’t know the rules; it’s one of the reasons we have the concept of first-time offender. And, if the rules hide inside the label you call someone, like ‘boyfriend’, you should make sure everyone knows what the rules are.”

Over 20 years later I was speaking with a recruiter. She said, “They’re looking for an IT Project Manager.”

To which I replied, “I don’t do well with labels. What would they be expecting this person to do? A sort of day in the life of kinda thing.”

She replied, “Project Manager things.”

This is referred to as a circular definition, which means I need to know the definition first. In other words, it assumes I know what is meant by Project Manager and what one of those does on a universal level.

“Thanks,” I replied, “I understand, but for them specifically. I’ve seen roles for Scrum Masters that read more like Business Analysts and vice versa. For them, specifically, what does the Project Manager label mean?”

When it comes to the contents of this book, I will do my best to use common language and common definitions, explain jargon when possible, and so on. Therefore, I don’t want to create “new” words and definitions while still respecting problems caused by our use of language. Further, I will avoid breaking out the thesaurus and using synonyms; therefore, “work” should always mean the same thing throughout Triumph over Time and a different word will be used only if describing a different concept.

For example, Risk Management as defined by the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK - pim-bock) is a practice of monitoring and tracking events with a potentially positive or negative impact on what you are planning to do or are already doing. The majority of common definitions, captured in dictionaries, for “risk” don’t allow for the concept of a “positive” risk. The common definitions being:

- a situation involving exposure to danger.

- [in singular] the possibility that something unpleasant or unwelcome will happen.

- [with modifier] a person or thing regarded as a threat or likely source of danger.

- (usually risks) a possibility of harm or damage against which something is insured.

- the possibility of financial loss.

- [with adjective] a person or thing regarded as likely to turn out well or badly, as specified, in a particular context or respect.

The last common definition in the list above is the only one allowing for a positive risk, which is the next to last definition from the Oxford English Dictionary. Therefore, while the majority of common uses don’t allow for the concept of a positive risk, the PMBOK and commercial fields deviate from that majority, this happens often. The use of the term “positive risk” can cause confusion or seem like an oxymoron if not used in contrast to the term “negative risk,” which is just a “risk” in the minds of most people.

For our purposes, I have chosen to call it “Event Management,” which comes with its own downsides.

“Events” are things that impact you from the outside world. This simple change allows us to reduce confusion when we say “risk” (or “threat”) and “opportunity” to describe a future possibility with perceived negative or positive impact, respectively.

There’s also the tense problem.

- A risk or threat is a future event with a perceived negative impact.

- An opportunity is a future event with a perceived positive impact.

- An issue is a present event having a negative impact.

- A reward (or similar) is what I refer to as a present event having a positive impact. I say, “I refer” here because commercial sources don’t offer a present-positive word for the same.

If “event” is the outside world acting upon you, “actions” are things you do to impact the outside world.

- A goal is a future outcome you give yourself.

- A request is a future outcome someone has asked you to perform.

- A performance is an action you are already doing, regardless of whether it’s a goal or request. (For the sake of humor and completeness, “work” is an action you are performing that you don’t want to, didn’t choose to, and find little-to-no enjoyment in.)

- An achievement is a past action with a successful outcome.

- A failure is a past action with an unsuccessful outcome.

To sum up, when it comes to language, I will do my best to be internally consistent, leverage context, use plain language, prefer common over commercial definitions, and keep it simple.

Tone

I’m kind of a chameleon. I grew up in a military family, moving to a new place every two or three years.

In adulthood, I continued the pattern of moving every couple of years. Sometimes, it’s just down the street; other times, it’s a few states away. Being dropped into a new place and culture gets me excited.

Basically, I get to ask myself, “How do I keep from getting beat up here?”

This shapeshifting is helpful with clients as well, be they corporate or non-corporate, individuals or groups, regardless of education or socioeconomic status.

Some want a harmony-loving monk most days. Some need a stern personal trainer on others. Others love a misanthropic curmudgeon professor. While others still appreciate a laidback spiritual guide with an unfailing love of humanity. I can be all of those while still being me because I’m more than one thing or type, and so are you. Some receive cursing and swearing better than proper and “professional” language; I can do both while maintaining the integrity of the message.

It’s not to say I don’t know who I am. Or that I’m hiding behind masks. Rather, I’m willing to shape my presentation to something more easily absorbed by the client.

(Something said by every humanoid alien from science fiction—ever.)

Unfortunately, with a book, I won’t be able to verbally bend and dance with you the way I normally could. Therefore, each chapter is written with different clients, friends, and family members I love in mind instead of pretending I know you or assuming that you don’t know me at least a little. If I try to speak directly to you, based on what I know of you, this book would be a dry and neutral read.

So, you may sometimes feel like I’m talking directly to you, and other times it may feel like you’re watching me talk with someone else.

Density

Triumph over Time is intentionally dense, which is to say we have done what we can to ensure each word, sentence, and figure is absolutely necessary to communicate understanding at a consistent level across the entire book while consolidating as many, related fields of study as possible.

The primary goal, as it relates to density, is to ensure you don’t become bored. This boredom is something I often noticed researching the book. Repetition of anecdotes and explanations, which lead me to often feel like saying, “I get it already, can we move on, please?”

I understand the various reasons for the repetition; however, I hope to walk a different path. Besides, if I did the same, even the audio version of the book would be multiple days long.

The metaphor I started using is that Triumph over Time is like a wine reduction. If the works of everyone referenced in the back of the book (and beyond) were analogous to grapes then, over the years, the ideas have had the chance to mature into multiple wines, each with a subtle nuance all their own.

I’ve taken them home. Tried them out individually, collectively at various ratios, and shared them with friends, family, and clients. Then, I poured what I hope is the perfect ratio into a pot, added subtle nuances of my own, and let it simmer, until all of it could fit into one bottle.

As such, you may find it beneficial to return on occasion to possibly pick up on something that was missed or misunderstood your first time through. (I already do this with many of the references in the back of the book.) Further, you may find yourself inspired to explore a topic in more depth. In other words, Triumph over Time is not intended as a “one and done” read and believes you are intelligent, creative, and curious.

With that said, feedback and questions, as always, are welcome!

Synergy

I don’t like the word synergy, to be honest. The impact the word should have is inversely proportional to its level of use. Synergy was a term used by some ‘90’s and early-aught CEOs to stand-in for “team player,” which was a stand-in for “fast-paced environment,” which was a stand-in for “What do you mean you’re only putting in 40 hours a week, you’re not gonna get a promotion that way‽”

Having said that, synergy is the most appropriate word in the English language for what we’re talking about in this book. Synergy is:

the interaction or cooperation of two or more organizations, substances, or other agents to produce a combined effect greater than the sum of their separate effects

You have a goal or vision. Having a good set of tools helps achieve it. Having a good set of practices helps as well. Good principles multiplies that. Good values multiplies it even more.

Individually, values, principles, practices, and tools improve your chances of achieving your goals effectively. Having said that, you can find greater and more holistic success if the individual parts build and strengthen one another.

Fifth Generation Time Management

There are many names we’ve tried to come up with for what’s in this book and the field or industry we practice in the real world. Time Management, Self Management, Stress Management, Productivity, Life Management, Project Management, Risk Management, Communication Management, Agile Software Development, Change Management, and so on. Each one has its nuance, positive and negative connotations, and proposed boundaries set by those who practice them.

For example, some say Agile Software Development should only apply to software, while others say the opposite. Most fields and industries have jokes about themselves. Some jokes were written by those practicing in the field.

One of the more popular jokes from the self-improvement field comes from poking fun at Time Management. They all start something like this: “Calling it Time Management is ridiculous. You can’t manage time, you can only manage…” actions, yourself, life, and so on. Calling the skill, practice, or profession “time management” is like saying you’re going to learn how to manage the universe; entirely beyond your influence and too big for your (or my) brain.

All fields have their heroes and heroines. Their contributions are downplayed and overplayed depending on who you talk with. The same is true for Time-self-stress-life-whatever Management.

As we seek differentiation, we tend to rename things. Either to differentiate “our thing” from “their thing” or to get away from a label that has gone sour, “Oh, it’s not Project Management, it’s Agile Software Development” or vice versa.

Stephen Covey is one such “hero” and the author of The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. When people in the Time Management field reference Covey, the Time Management Matrix is often brought up as his seminal contribution to the field of self-management. I disagree. In fact, I barely recall or credit Covey with the Time Management Matrix at all, if for no other reason than it is one idea in one chapter of a much larger work and body of work. The Time Management Matrix is laid out when Covey describes the four generations of time management.

In short, the first generation is getting what’s in your head into the world in the form of notes and checklists (to-do lists). Second generation becomes future-oriented with calendars and appointment books. Third generation introduces the concept of values (personal or collective) and prioritizing based on those values along with short-, medium-, and long-term goals and daily planning to the achievement of those goals. Fourth generation focuses on maintaining production and production capability by way of interpersonal relationships and results-orientation with a further emphasis on being principle-based and character-centered. Each generation adds to the previous more than it abandons or replaces things.

In the case of time management, Covey’s work is focused on the fourth generation using what he called the Time Management Matrix to describe the point behind a planning method. You want to spend most of your time in Quadrant II in order to become what he called a Quadrant II Self-Manager.

What does that mean?

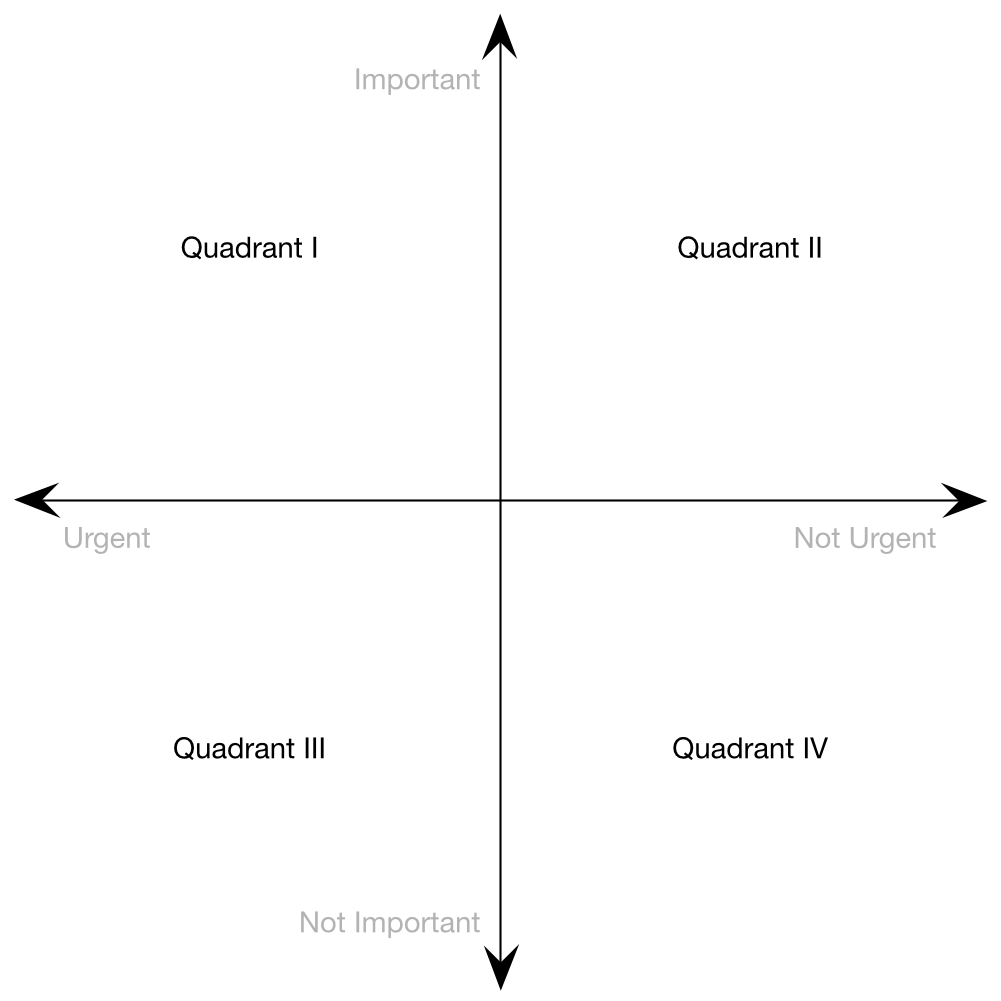

Imagine a chart where the X-axis represents urgency and the Y-axis represents importance. If divided in fourths you end up with four quadrants, important and urgent, important and not-urgent, not-important and urgent, and not-important and not-urgent. Quadrant II is the top right corner, and contains things that are important and will rarely, if ever, become urgent; namely reflecting on and building character does not help you while your house is on fire with you in it.

Spending most of your time in important and urgent or Quadrant I, can burn you out. Spending most of your time in not-important and urgent or not-important and not-urgent, Quadrants III and IV, may end up with you becoming irresponsible. Spending most of your time in important and not-urgent, Quadrant II, is where discipline and balance are achieved, according to Covey.

Some have interpreted this matrix as a way to manage your to-do list; if the item is important and due soon, put it in Quadrant I and do it. Once Quadrant I is clear, start working on Quadrant II things so they never become urgent. This is not a bad idea; however, it is not related to Covey’s work directly, in my opinion.

When The Time Management Matrix is attributed to Covey, it is often related to this to-do list management method. However, Covey recommends leveraging calendars based on vision, roles, and goals to “put first things first” not the time management matrix.

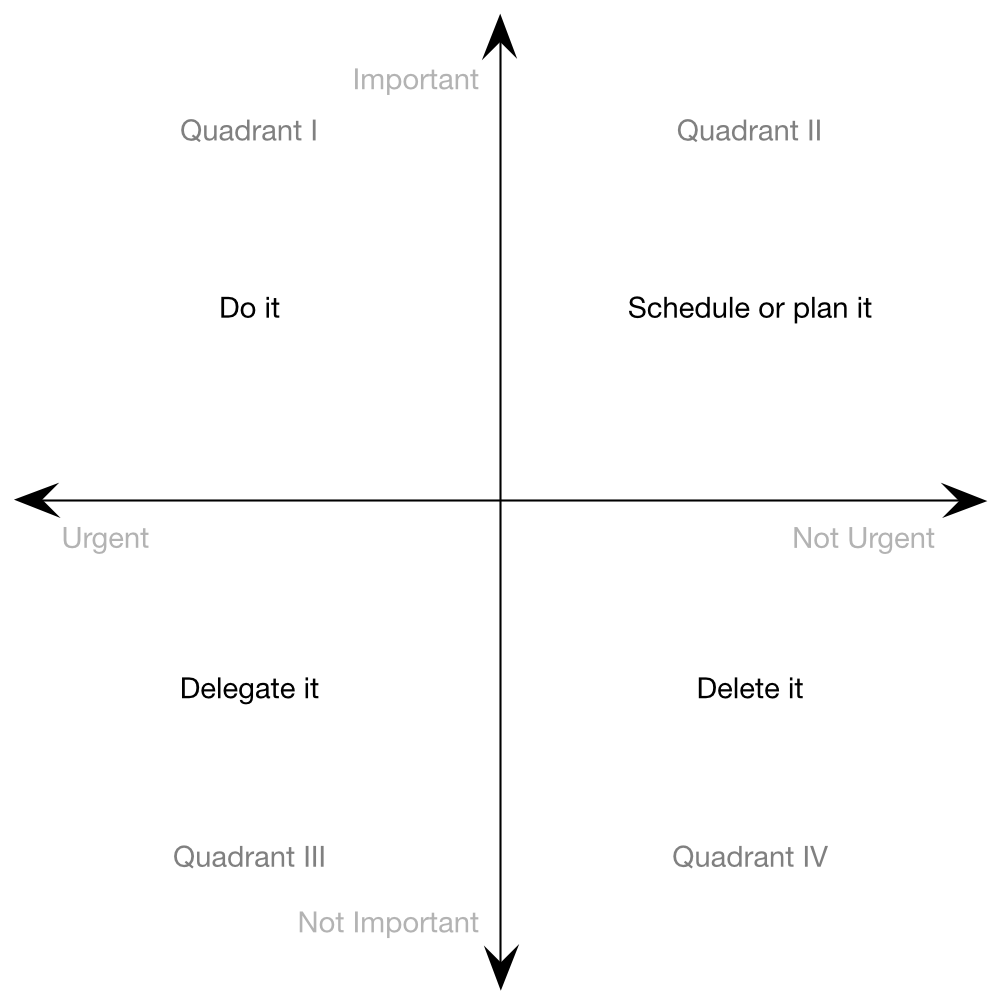

Using the matrix as a to-do list management tool is more like what’s been called the Eisenhower Box.

The Eisenhower Box was definitely named after President Eisenhower and possibly used by him to make some decisions, though the jury’s still out. Quadrant I is fire fighting; do the thing. Quadrant II is for things like long-term strategic planning or getting down to the gym; schedule the thing, which does tie to Covey, indirectly. Quadrant III is mostly meetings; delegate the thing. Quadrant IV are time wasters and most leisure activities; delete the thing.

There’s debate on the origins of the Eisenhower Box. Did Eisenhower invent it? Was it derived from a quote of his? Did he use it? That sort of thing.

Regardless, I don’t see The Time Management Matrix and The Eisenhower Box described to the same purpose in the same sources. Further, given the prescriptive nature of The Eisenhower Box and Covey’s own words, I see them as using the same model in two different ways.

If you’ve heard the allegory of the jar with the rocks, pebbles, and sand, fourth generation thinking is where that comes from. It’s easy to tell we’re still coming to grips with the fourth generation, given the explanation I felt was necessary, which is fine.

I also think we’re coming to recognize a fifth generation, which is focused on agility, flow, purpose, and, by extension, mindfulness.

Triumph over Time hopes to help usher in the fifth generation without emphasizing a specific approach or vantage, which is in keeping with the fifth generation itself. I will use comparison to describe what I mean by not emphasizing an approach or vantage.

In personal productivity, I have found three popular resources, relatively speaking, that can get you very close to a fifth generation system. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People by Stephen Covey, Getting Things Done by David Allen, and The Pomodoro Technique® by Francesco Cirillo. Each one takes a specific approach and vantage.

Imagine a mapping application. When zoomed out completely, you are at the highest level. You have a vantage with great breadth but little depth and detail. Now imagine looking at an image of the street view little breadth but great depth and detail. Transferring to the forest metaphor, the highest level is the territory or region, and the street view is the undergrowth on the forest floor.

The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People takes a region-first approach and can get you to the forest and some of the trees. Getting Things Done takes a trees-first approach and can get you to the undergrowth with little knowledge of the forest whatsoever. The Pomodoro Technique® takes an undergrowth-first approach (or walking down a street by way of the street view images).

The first focuses on values, principles, and people. The second focuses on processes, tools, and “being like water” (agility and flow). The third focuses on becoming focused (flow and mindfulness).

They all have parts of the others. In some cases, it may only be one sentence. Further, each is geared toward, though not necessarily made specifically for, different types of thinkers. If you tend to be what we call a strategic thinker, the top-down approach of Covey might be your preference. If you’re what we call a tactical thinker, the bottom-up approach of Allen might be more your thing. If you’re extremely detail-oriented, find your focus failing, or have issues with interruptions or distractions, The Pomodoro Technique® might be the best place to start. If you are, or want to be, someone who can transfer up, down, and side-to-side with ease, at-will, and with purpose, you might prefer Triumph over Time’s similar depth across the entire breadth approach.