Knowledge

The Knowledge Economy

Knowledge is a vastly under rated and unvalued corporate asset. Whilst the ‘bean counters’ look at the ‘bricks and mortar’ they almost invariably fail to put a value on the knowledge that resides within their employee’s heads. This failure to recognise true value is a failure of the business itself.

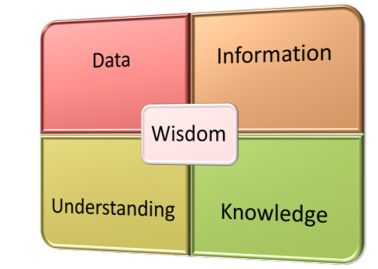

Enterprise Architecture and the Knowledge Hierarchy

Every business, as it matures, is required to traverse the Data to Wisdom Hierarchy. How far it progresses and to what extent can determine the success or otherwise of the business itself.

- Data: Is the product of observations of people and measurements and facts about the world in which the business resides.

- Information: Is contained in the description of the data. It adds context through the application of patterns and structure allowing for the answers of questions such as who, what, where, when and how many?

- Knowledge: Is attained in the ability to define what the information patterns mean in relation to the business and to consequently being able to apply the definition to create predictable future outcomes.

- Understanding: Is the state where explanations of how and why the patterns exist can be expressed. Plausible predictions arising from being able to consider the actual causes relating to a business situation. Understanding allows for answering the question ‘Why?’

- Wisdom: Provides the ability to perceive and evaluate the long-term consequences of behaviour allowing the business to better decide what to do when confronted by a situation in which it may or may not have experience. Wisdom allows for reliably being able to answer the question ‘What if?’

An Enterprise Architecture provides a means through which information on data collected from within the business can be contextualised, structured and analysed. Depending on how an Enterprise Architecture is expressed it may also provide predictive tools supporting the realisation of understanding and the acquisition of wisdom.

An Enterprise Architecture by itself contains neither understanding nor wisdom. Both of these states however can be realised in individuals using contents of the Enterprise Architecture to provide them with the necessary insight.

Knowledge as an asset.

I have heard it often suggested when discussing the value of knowledge that being regarded as intangible it is not quantifiable and consequently it is not counted as a real asset.

I would contend that the difficulty in measurement is only a consequence of a lack of desire to do so. Because it may be hard to measure does not make the effort to do so unnecessary nor the rewards of having done so trivial.

Individuals, Intellectual Capital and corporate assets.

I acknowledge that the value of Knowledge is extremely difficult to quantify. I rarely see any attempt to recognise that Knowledge has any value at all. Key individuals who, if they were to depart, taking with them significant Intellectual Capital, would severely damage the ability of a company to operate are assets that should be preserved. It is too late to realise the value to the knowledge asset after the fact.

I would also suggest that the business which actively engages in assigning value to the knowledge they hold and consequently having improved understanding are significantly better placed to take advantage of business opportunities when they arise, understanding their capabilities as well as their potentialities.

Dangerous Knowledge

Albert Einstein famously said that “a little knowledge is a dangerous thing. So is a lot”.

However it is neither having a little nor too much knowledge that is dangerous but in believing that there is no more to know.

Where knowledge is captured within a business it is important to appreciate context, quality and scope. Realising that there is always more to know ensures that assumptions can be better identified for what they actually are and the confidence in any risk mitigation strategies developed to support the business are more appropriate.

It is knowledge without wisdom that is the truly dangerous thing.

Dynamic Knowledge

Knowledge is rarely if ever an absolute and should be continuously tested against the current reality. New information received can and does alter the perception of what has been held as truth. A person residing in the Middle Ages had no issue with ‘knowing’ that the world was flat. Newtonian physics was regarded as being absolute fact until situations were encountered that did not ‘fit’.

As well as new information having an impact on the validity of what is known so does the framework within which it is applied. We know for instance that 1+1=2. This is certainly the case generally but not when working in a binary framework where 2 does not exist in this framework. We now need to know that 1+1=10.

There are also cultural differences that can affect how knowledge can be applied. In any homogeneous environment knowledge of body language cues relating to such things as ‘eye contact’, ‘gestures’, ‘personal space’, ‘hand shakes’ can be readily learned. Communication however, if this knowledge is applied in a different cultural environment, can be significantly and adversely disrupted.

Knowledge acquired should not be regarded as sacrosanct. It is always subject to change depending on the facts available. It is also open to interpretation depending on the framework in which it resides.

Knowledge is dynamic, responding to the world.

To know does not mean to understand.

Having all of the available facts does not automatically mean that you understand all.

Facts by themselves can and frequently are interpreted in multiple ways dependent on the world view or paradigm that the perceiver works within. Demonstrable in the situation where two individuals, each presented with the same facts, can and do arrive at either different conclusions or make different and possible contradictory decisions.

The provision of an Enterprise Architecture within a business context is an attempt to qualify the facts collected by exposing how they are inter-related. By having a tool that can potentially support predictions on the outcomes of the decision making process the different interpretations of the ‘original facts’ becomes less of an issue.

An Enterprise Architecture can assist in the conversion of knowledge into wisdom with the business gaining significant benefit as a consequence.

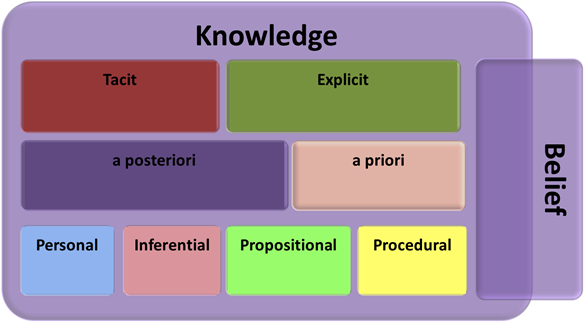

All knowledge is not equal.

When exploring the possibility of building a repository of business knowledge it is worth understanding that knowledge presents itself in many different forms and should consequently have different treatments and perhaps different values associated to it.

It is generally understood that knowledge can be categorised as either being:

- Tacit Knowledge: this is knowledge that is embedded within individuals and is based on their own experiences and involves such intangible factors as their personal beliefs, perspective s and values.

Tacit knowledge forms that invisible, influential part of organisational knowledge, subtly driving the organisational culture, relationships and capabilities.

Tacit knowledge is often difficult to articulate and consequently hard to communicate and store, it consists of non-codified content. Being resident exclusively in the human mind, it can be communicated through face-to-face contact and the telling of stories. Sharing of tacit knowledge which is “owned” by the individual is realistically the only way that this can be preserved within a business. Losing a ‘sole owner’ of tacit knowledge can be disastrous.

- Explicit knowledge: is knowledge that can be fully articulated and consequently captured and transmitted. Being easier to articulate, communicate and store, explicit knowledge can be codified and stored in artefacts such as documents (paper or digital) or databases. Explicit knowledge can be “owned” solely by the organization and is not dependent on the individual.

Tacit and Explicit Knowledge are however fairly course grained categories. To be able to best assign some value to either we should also look further. At the highest level Knowledge has an additional classification in that it can regarded as being

- a priori knowledge which is gained without needing to observe the world and

- a posteriori or empirical knowledge which is only obtained after observing the world or interacting with it in some way.

Other means of categorising knowledge encompass:

- Personal Knowledge: is knowledge of acquaintance and is gained through experience. This knowledge can be affected by personal belief systems. Belief systems are a powerful influencer of personal knowledge. A person, believing something to be true, with neither personal experience nor evidence to support it may presume this to be knowledge and communicate it as such.

- Procedural Knowledge: describes how something can be done. People who claim to know how to operate a computer, or model the business using software tools, are not simply claiming that they understand the theory involved in these activities but are claiming to possess the skills required to do them. Knowledge of this type could be said to be “know how knowledge”

- Propositional Knowledge: or descriptive knowledge is the knowledge of facts. These will be supported by ‘scientific’ or observable evidence. By its very nature knowledge of this type can be expressed in declarative sentences or indicative propositions.

- Inferential knowledge: is based on reasoning. It is established though taking facts and/or theories and inferring something new. This knowledge may not be verifiable through either observation or testing but can be a powerful tool asset in supporting the decision making process.

Understanding the source of knowledge and how it has been established provides significant value to its user. Being able to adequately deal with personal and corporate beliefs is important. It is possible to believe yet not know or know yet not believe.

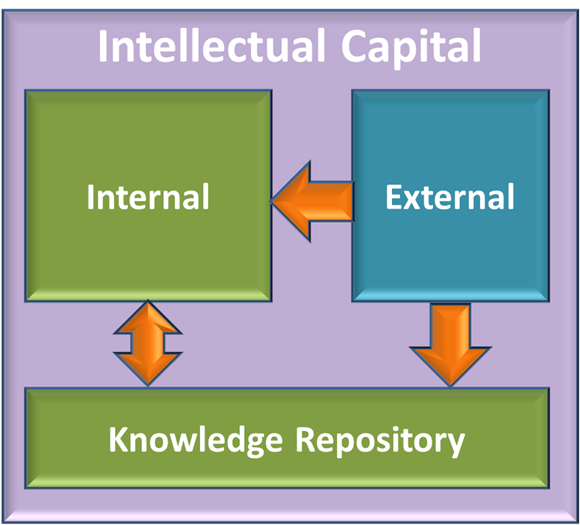

Harvesting Intellectual Capital.

Intellectual Capital within a business is an asset that should be enhanced whenever possible. Frequently, when undertaking activities that lead to increased capability, improved business processes or perhaps more efficient operations and where external resources are utilised, the opportunity of harvesting new knowledge is overlooked.

Having an established knowledge repository from which internal resources can draw will provide a valuable supplement to what they already know. With a knowledge repository being fed with additional information the reliance on external resources can become less critical. Where external resources are engaged to fill an identified knowledge and skills gap, processes should be enacted that harvest as much of the missing knowledge as is possible for future reference.

Hand in hand, with the increase in Intellectual Capital within the business, so does its maturity increase. With more knowledge ‘in-house’ and accessible, better decisions can be made and the business can become more self-reliant and less at the ‘mercy’ of external vendors.

So often it is the external resource who walks away from a business with increased knowledge of how the business operates, making them more marketable back to the business itself or to its competitors.

By harvesting Intellectual Capital and applying it where and when appropriate a business will, over time, reap significant business benefit.