Business Performance

Quality information and analytics

A business leader in order to make decisions that have real worth must be well informed. Consequently presenting a view of a changing and ever evolving business to the business that is clear, unambiguous, concise and timely is a real challenge that must be met.

This must be supported by the capability to rapidly analyse significant quantities of information, establishing intra and inter-relationships between seemingly unrelated data and applying collective wisdom so as not having to rely too much on the crystal ball.

Motivations and Measures

Identifying key business motivations and measures are two requisites to building a successful Holistic Architecture.

Knowing why you are designing the component you are and what will be the consequence of doing so provides clarity to the architecture development process. The measures in particular give you the opportunity to determine the effect of your design on other architectural components.

Unfortunately uncertainty seems to be a fact of life when establishing any architecture. The risks associated with this uncertainty however can mitigated to some extent when there is some understanding and application of the business measures and motivators. ‘Why’ and ‘what is the impact’ are crucial questions in the decision making process.

Qualifying assumptions

Whilst acknowledging that capturing ‘all’ information relevant to making a decision about implementing a business initiative is not possible there is a real issue that needs to be addressed with how assumptions are managed.

Often an assumption is accepted as being a fact. Its unqualified acceptance can result in significant and unmitigated risk to the initiative’s eventual success.

The scenario, for a hypothetical initiative, is that an assumption is made that, if executed, will result in a business increasing its customer base by 50%. In building a business case this increase is expected to translate, based on known customer behaviour, to an increased peak transaction load on whatever system is developed to host the initiative of say 10,000 transactions per hour.

With the assumption accepted, as is the transaction rate, with other perhaps known information and other assumptions some benefit of the initiative to the business could be established thus providing an indication of its feasibility.

To make a good decision however the assumption initially made should have been qualified.

By supporting the assumption with statements such as ‘based on market research it is expected that the customer base will increase by 30% plus or minus 20% with a confidence level of 30%’ can have a profound effect on decisions eventually made. The assumption, now qualified has a best case of achieving a 50% customer base increase but has a worst case of 10%. The business case benefit, driving the decision, without having further quality information, must now be suspect.

The lesson here must be that before making a decision based on assumptions ensure that they are qualified.

Balancing decisions against risks, costs, benefits and business goals.

At some point in establishing the business case to support a business initiative a decision needs to be made either to proceed or to not proceed. In building the business case information will have been gathered and collective knowledge will have been applied to determine it adequacy.

Risks will have been identified and presumably the cost of mitigation coupled with both their impact and the likelihood of their occurring will have been established.

A decision can be reached by balancing the benefits of the initiative against the cost of implementation, the impact on the business if it is not and the importance of its contribution into the realisation of Business Goals and Strategy. This decision needs to be also made with an appreciation of other competing initiatives in the pipeline.

Managing Risk

Managing risk is absolutely essential if you wish to optimise the benefit of a business initiative. That there will be risks is unavoidable. Identified risks can be managed through either avoidance or mitigation.

With risk avoidance, activities are undertaken in order so the situation that would trigger the risk can never happen. Mitigation however assumes the risk will be realised but plans or subsequent actions put in place that will lessen its impact.

To optimally manage identified risks it is also necessary that two of their attributes are understood.

- Likelihood of a risk being realised: This can be expressed in terms of a level of confidence.

- Impact if realised: This may be the dollar cost to the business.

Both of these attributes may consist of a range of values with the risk perhaps being expressed as having a range of possibilities.

In both the case of risk avoidance and risk mitigation there will be a cost associated with its achievement. These costs must also be identified.

With a good understand of the likelihood of a risk being realised, the impact on the business together with the cost of dealing with it, the feasibility of a executing a business initiative can be better assessed.

Performance metrics – supporting Service Delivery?

Performance metrics are often established as a mechanism to establish the effectiveness of a business and the delivery of its services. Who, however are the metrics designed to assist.

Over the last three months I have been an active user of mixed-mode public transport in order to attend my distant workplace. The daily commute is long and encompasses the use of buses, metropolitan and regional train services. Over a period of time I have been able to garner first hand a strong impression of the level of performance delivered.

The public transport authority responsible for regulation of each service publishes a set of performance metrics which, if they are met, result in an incentive payment made to each operator. A penalty is imposed on failure to deliver.

The main metric used relates to what is called ‘on-time’ performance. This describes the parameters within which a Service is regarded as ‘on time’

- 77% of Metropolitan trains must arrive at its final destination no more than 59 seconds early or 4 minutes 59 seconds late.

- 92% of Regional, short haul trains must arrive no more than 5 minutes 59 seconds late.

- Buses must arrive at their final destination no more than 2 minutes early or 5 minutes late and with no timetable service operating early at any point of their route and 90% of services running on time.

Whilst each of these are well defined metrics providing each operator with a statistical target to achieve in order to receive an incentive what do that actually mean to the paying customer.

Experience has shown me that in the three months of travel that the bus and metropolitan trains generally meet their ‘on-time targets’ although the frustration experienced in seeing a bus running 1 minute 45 seconds early when I am on the other side of the road is significant. It may have been ‘on-time’ but without me on it may as well have been 20 minutes late, being the wait for the next service.

I also have issues with a service which, on some lines where there is a frequency between trains of less than 5 minutes, at certain times of the day, allowing as acceptable the targets set. A ‘late’ train on such a service seems indistinguishable from a cancellation.

I am also yet to meet the member of the travelling public who actually finds it acceptable to have 23% of their metropolitan train services not run ‘on time’. The business impact of a public transport travelling workforce being late for work at least once per week is likely to be significant.

The Regional train I use is mixed in its service delivery. I have been able to rely on it delivering me to work on time in the morning reliably. Going home however I have yet to arrive at my destination ‘on time’. Consequently my experience of the Regional Service is no better than 50%. But of course from the operator’s perspective it is the statistical figure over the entire transport network that is important.

The performance metrics set seem designed to support the cash flow of the operators. Setting the thresholds low maximises operator’s profits.

The operator is likely engaged in applying a typical saddlepoint analysis strategy. Setting the threshold low enough that they can earn the maximum incentive from the regulator yet not so low that they will drive away their customer, the travelling public, thus optimising profit.

What, however was the original purpose of establishing these performance metrics?

Were they designed as an aspirational target through which service delivery to travellers could be improved or was it set purely for financial purposes?

In this instance I will maintain my cynicism.

Enterprise Architecture: Baselining Performance Metrics

Being able to demonstrate the benefit of undertaking Enterprise Architecture requires, like other business initiatives, the establishment of appropriate performance metrics. Being able to provide quantifiable validation that Enterprise Architecture activities actually contribute value to the business can enshrine its ongoing use.

In establishing performance metrics it is important that they have resonance with the business.

High level KPIs such as:

- Identifying reuse opportunities

- Identifying functional duplication

- Reducing design rework

need to be expressed so that the business can on any particular initiative can quantify the actual benefit;

- Initiative A Identified x reuse opportunities

- Initiative B Identified x functions that have been duplicated resulting in a reduction of project scope

- Project C reduced design and development rework by x%

Each of these could be quantified with both a financial and time to implementation benefit (saving $y and z man days of effort).

One obstacle to being able to quantify these benefits is however not having a benchmark in place from which the benefit can be measures against.

Being able to answer the questions ‘what is the value to the business of being able to reuse components already developed?’ and ‘what was the cost of developing the function that you avoiding duplicating?’ ‘what is the cost of rework?’ needs to be answerable.

Going ‘hand in hand’ with a developing Enterprise Architecture is a business that is baselined. Knowledge and understanding of where the business is, what costs it has incurred getting there and why becomes an important asset for realising future benefit.

The likelihood that this baseline knowledge exists is often low but with effort can be established whilst the Enterprise Architecture matures.

A measure of success.

The ability to be able to measure success within a business is fundamentally dependent on having already established the criteria against which the measure is being made.

In establishing a business case to support the development of a business initiative it is critical that the benefits expected to be realised after execution are fully defined. The quantification of these benefits provides the basis against which the success of the initiative can be assessed.

Similarly when maturing the capabilities within the business, in response to delivering against defined strategy, the only way of really knowing if progress is being made is through having a quantitative understanding of the capabilities before any change was invoked.

Establishing a measurement baseline, then continuously assessing how it alters as change is implemented, provides at least one dimension of measuring the success of a business initiative.

KPIs and the business

The establishment of Key Performance Indicators (KPI) within any business is absolutely essential. Aligned to strategy they provide the means by which the health of the business may be properly assessed.

KPIs should be set early to support the achievement of business goals and objectives. Once established at a high level they should be able to be decomposed so that business activity, no matter, how fine grained, can have its contribution traced to it source.

Having processes are in place that ensure that metrics are captured then measured against the planned or expected outcomes permits decision makers to determine if remedial action is required to compensate for any negative results.

The feedback provided by having reliable metrics enables the opportunity to engage in business process improvement or to refine business strategy and the consequent business goals and objectives to reflect reality.

Without the definition and on-going management of KPIs a business can have no real insight into how it is performing.

Without insight the business risks failure.

Assessing Process Value

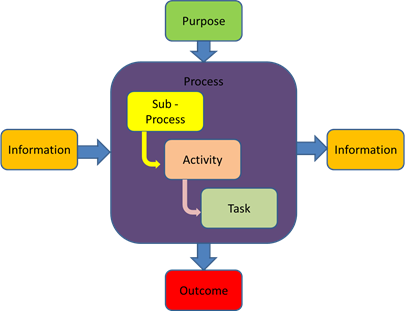

Processes define how the business actually interacts with the world. Each process must have a valid purpose that assists with the delivery of the business strategy. Each process and its component parts will have an outcome that can be measured for its efficacy.

Central to understanding how the business operates and how to potentially improve that operation is gaining an appreciation of how processes interact with one another and how changes to their structure and flow can affect associated business outcomes.

Processes are rarely stand-alone, being triggered by some upstream event or outcome resulting from another process. Physically documenting how each process works: how it interacts with others and what information is flowing (from what and to where) assists in the gaining of an end-to-end view of what is happening within the business. By overlaying key measures such as

- Cost of operation

- Time taken to complete

- Step and total value earned

the effects of change on business benefit can be better assessed.

Leveraging the Value Chain

Having defined processes within the business and having also established performance metrics deemed necessary to assess their respective health the building of Value Chains, providing a high level view of how aspects of the business operates, is essential.

A Value Chain provides the mechanism through which a sequence of relevant high profile activities or processes can be linked so that a targeted performance metric may be analysed.

Exploring a Source to Sell Value Chain for instance allows each step in the process from which raw materials are sourced through to their being changed into a product which will ultimately be sold to a targeted customer to be visualised simply.

Each step of the process has a cost associated with it as well as contributing to a change in the value (this could range from financial value to customer satisfaction), either positive, negative or no impact of the product to be sold.

Assessing the changes within the Value Chain provides the opportunity to identify parts of the process that are less than optimal and consequently adversely affect the end result. In identifying poor links in the chain remedial action can be taken to rectify potential problems.

It should however be noted that a Value Chain analysis should explore multiple performance metrics as there is likely to be some form of interdependence between them. The remediation of one link in the change for one metric may have adverse effects on either itself or another link for another metric.

The Value Chain provides a useful tool for both assessing the health of the business and the targeting of specific components that would benefit from Process Improvement or Re-engineering.

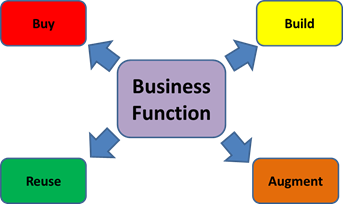

The case for Buy, Build, Augment or Reuse.

Many businesses, for better or worse, decide on a single policy such as ‘Buy before Build’ when looking at implementing new business capability. The rationale behind such a policy is sound in that the design and development work to implement supporting business functions is effectively outsourced to a third party provider. By purchasing a COTS (Common Off The Shelf) software package the business has delegated the support of the business functions away from themselves. The question should be asked: “Is this best for the business?”

A significant issue of a ‘Buy Before Build’ policy is that the purchased product is likely to exhibit the required functionality in a different manner to that which the business actually wanted. Unless the business is then prepared to go down the customisation path the _only _option open to them is to change the business to suit the product.

A secondary issue of this policy is that over time the business will accumulate duplicated functionality as purchased products have overlapping feature sets. This duplicated functionality may be used by different parts of the business necessitating variant processes to achieve the same or similar outcomes. Having worked for one company where it was widely regarded as being the ‘Noah’s Ark’ of the IT world (they had at least two of everything) the duplication did cause confusion.

Rather than adhering to a strict policy perhaps a guideline could be put in place that explores the different options available to the business:

- Buy - Purchase a product when it closely satisfies the required functionality and there are no other options.

- Build - Develop a system that delivers the required functionality when there is no product available to purchase or other systems available.

- Augment - Modify an already existing system to provide the additional business functionality.

- Reuse - Leverage business functionality that already exists within existing business systems.

By looking at the range of possible options and associating each with a set of costs and benefits a better decision can be reached on how new business capability can be implemented. This should be undertaken in association with an analysis of how each option would impact other existing systems.

Business Architecture and Benefits Realisation

In the ‘ideal world’ all business activity would be undertaken in a manner that moved the business closer to achieving its ‘vision’ in an efficient and most cost effective manner.

Unfortunately, living in the ‘real world’, the truth falls far short of the ideal.

The intent of Benefits Realisation within a business is about ensuring that ideas and consequently projects deliver the benefits, forecast and identified in a business case or project charter documents and are aligned to business strategy.

The steps in doing so should be straight-forward however the reality is that many projects fail to deliver the benefits. Worse still, many fail to even identify what the benefits are other than superficially. Common pitfalls such as expecting that technology will deliver the benefits whereas, whilst it may contribute, it is likely that it is the business change that will deliver the results.

Benefits don’t just happen. They need to be measured and managed.

- Align to Strategy: Ideas and resultant projects should support Business Strategy. If there is no alignment why do them.

- Identify Benefits: What benefits can realistically be expected.

- Identify Measures: How will these benefits be manifest and how will they be measured

- Conduct Baseline Measure: Need to have a baseline against which the measures can be compared.

- Implement Change: Execute the change within the business that the project has defined.

- Monitor: Capture measurement details.

- Assess: Compare measures benefits with the expected.

- Realign to Strategy: Feed results back into the strategy and refine as required.

A Business Architecture provides a structure which supports the Benefits Realisation process. It allows competing ideas and potential projects to be prioritised by identifying early on what business benefit is expected. By providing end-to-end visibility of the business it can assist in identifying key components of potential change and where measures should be made.

A Benefits Realisation Process is not difficult to implement providing the business has sufficient knowledge of how the business operates and the discipline to carry it out.

Business Goals must be defined and then measured.

All organisations should have formulated a set of goals and objectives, derived from their mission and vision statements and supporting their business strategy. The completeness of these goals and how they are managed can influence the of the organisation to be a success.

Having established goals provides real focus and ensures, with the assistance of governance and compliance processes, that all functions and elements within a business are moving in a common direction.

Without goals:

- the business lacks specific direction

- is without focus and

- has everyone, in the worst case scenario, doing their own thing

As progress is made in realising business goals a regime of monitoring real performance is essential. With consistent monitoring

- Progress against a plan can be reliably reported.

- Accountability for either success or failure is improved.

- Where issues or risks are identified the facilitation of corrective action or mitigation strategies is enhanced.

- Feedback supports improved strategic planning and future goal setting.

With well-defined business goals defined a sense of real purpose will be apparent within the business. With tangible and achievable measures set individuals within the business can experience a true sense of achievement during the journey of achieving those goals.

Enterprise Architecture – A measure of success!

Having spent time and effort in populating an Enterprise Architecture its true value can now be realised in its use.

The Enterprise Architecture, being a tool that provides visibility of the business, providing ‘line of sight’ between strategy and execution, allows it user to gain insights that would otherwise be obscured.

With being able to ‘slice and dice’ the business, the capability to assess the impact of change and the carrying out a ‘what if analysis’ on areas of interest is greatly enhanced.

The key to determining impact is the identification and inclusion of Business Measures within the Enterprise Architecture and their ongoing monitoring as part of ‘Business as Usual’ activities. The measures, once established, will be influenced by many different parts of the business and need to be looked at holistically as a change in one area may have a consequential change elsewhere.

Business measures must also not be looked at in isolation.

For instance:

- Increasing revenue by increasing prices may provide a short term gain but might be at the expense of customer satisfaction and market share

- Increasing efficiency or productivity may come at the expense of employee satisfaction.

- Driving down costs may come at the expense of revenue and customer satisfaction.

- Revenue may have increased through no reason than population growth yet if market share has decreased is this a success.

Business success should be assessed by taking a multi-dimensional view of the business. Success will be measured through the contribution of multiple individual measures and the context in which they taken.

It is reasonable to assume that if a business manufactures more of a specific product for sale then both revenue and the cost of manufacture will increase. Success here can, simplistically, be assessed by looking at the interplay between these two measures.

- If increased production equates to increased profit then does it matter that costs have increased?

- Does increased sales equate to increased customer satisfaction and give some consequential additional benefit?

With Business Measures firmly entrenched within an Enterprise Architecture and processes in place that use them and are rigorously enforced, a business will be in an excellent position to shape its future and be ‘successful’.