1. Getting started with NeuroTask Scripting

1.1 What are scripts and why do we need them?

Suppose, you want to make an experiment where you present eight words on the screen, one by one. Each word is to be shown for 2 s, followed by a 1 s pause. After all the words have been presented you want to ask the subject to type all the words rembered into a large text area in any order. In other words, you have a plan for the experiment that specifies step-by-step what you want to happen. If you wrote down these steps, it might look something like:

- Show word 1 for 2 s

- Pause 1 s

- Show word 2 for 2 s

- Pause 1 s

- …

- Show word 8 for 2 s

- Pause 1 s

- Have subject write down the words remembered

This plan for an experiment is in fact already very close to a script. The only difference is that scripts use specific expressions and statements to tell the computer what you want to do. A NeuroTask Script that would do the above would look something like this:

//

text("word 1");

await(2000);

clear();

await(1000);

text("word 2");

await(2000);

clear();

await(1000);

...

text("word 8");

await(2000);

clear();

await(1000);

largeinput("Write down the words you remember");

The dots, …, above refer to words 3 to 7 which for reasons of space have been left out both in the plan and in the script.

As you can see in the script, there appears to be an instruction to the computer to show a word. This instruction is called text. There is also an instruction to wait until 2000 ms have passed, where the waiting instruction is called await. Then there is clear, which clears the screen from any words and finally largeinput, which shows a large input area where the subject can type words remembered.

You will also notice that there are parens (i.e., round brackets), quotes, and semi-colons. All of these are added to indicate to the computer what you want it to do. Once you know how to convert your plan into a script, you can instantly run it on the internet.

1.2 Scripting psychological experiments

So, we saw that scripts tell the computer what stimuli to present and which data to collect from the subjects. The team at NeuroTask Scripting has tried very hard to make often occurring experimental tasks easy to script, even for a beginner.

NeuroTask scripts are programmed in JavaScript, the programming language that is built into all internet browsers such as Internet Explorer, Safari, Chrome, and even the browsers on your smart phone. This means internet-based experiments created with NeuroTask Scripting will run on virtually any computer with an internet connection. Creating web-based experiments from scratch, i.e., without NeuroTask Scripting is quite difficult. With it is a breeze. It is quite feasible to write a full-blown experiment in one hour. But don’t take our word for it. See for yourself.

For those of you, who are already experienced JavaScript programmers, it is important to know that we are not limiting your use of JavaScript. Also, all of the Dojo and jQuery libraries are at your disposal, included by default, and it is possible to pull in other libraries as well. We are in fact using a superset of JavaScript, called StratifiedJS, which adds even more functionality and additional (optional) libraries.

Writing scripts

There are two steps in creating an online experiment script, where step 2 is optional:

- Write your experiment script

- (Optional) Make and upload your stimuli

You’re done! Your script is ‘live’ on the internet and it has its own unique web address (also known as URL). You can now email this web address to friends and family, put a link on Facebook, etc. If participants do your experiment, their data will automatically be saved in your NeuroTask Scripting account, where you can easily download it in Excel or other formats. This is the way to go with pilots or informal experiments, or even with large experiments, for example, if you are using subjects from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk.

Inviting subjects

NeuroTask also provides facilities to

- Create subject records if you know the subject’s E-mail address

- Create personalized invitations to your experiment; NeuroTask will then E-mail subjects for you

Then, wait for the data to come in and start analyzing. While you are waiting it is possible to see who has already completed your experiment.

1.3 Scripts

The structure of an experiment script

Most experimental tasks in psychology involve about the same steps. The steps must be expressed somehow in a script. Typically, an online experiment will

- Welcome the subject,

- Ask for informed consent,

- Give instructions,

- Present stimuli, such as words, and

- Record responses, e.g., words recognized. This is followed by a

- Debriefing, where you may thank the subject for participating

Let’s look at a short example script that does most of this.

Your first script: A small experiment

Guess what the following script is doing. OK, the title sort of gives it away, at least if you have followed an introductory course on psychology.

1 //

2

3 text("Try to remember the following three letters");

4 await(5000); // 5000 ms or 5 s

5

6 text("YHZ");

7 await(3000);

8

9 text("Now, count back in threes starting with 307: 307, 304, 301,...");

10 await(25000);

11

12 input("Write down the letters remembered","brown_peterson");

13

14 text("Thank you for participating!");

15 await(3000);

If you actually did the experiment, you would see a white screen (i.e., web page) with the words “Try to remember the following three letters” (the quotes would not be shown).

After five seconds, the text changes into “YHZ”.

Then the count-back instruction appears with a longish 25 s wait, during which the subject is supposed to count back in threes.

After this interval, a text area appears with the label “Write down the letters remembered” above it. There is an “OK” button below the area.

After pressing “OK”, the thank-you text appears for 3 s and the subject is finished.

Though the script is short, it contains most of the steps of a standard experiment, and it can easily be changed to other stimuli, as we will illustrate below. The presentation time of the text may be varied from very long to ultra short, instructions may be made more complete, and so on. So, we see that this brief script is a miniature model for a whole range of memory experiments.

The Brown-Peterson Task is a classic experiment in memory psychology in which first John Brown in 1958 and later Lloyd and Margaret Peterson in 1959 showed that even three letters are forgotten in as little as 15 seconds, but only if the subjects are not allowed to consciously rehearse them. This is typically prevented by having the count backward in the threes. The effect is not obtained, however, in the first trial, i.e., after having studied and remembered just one letter triplet; the task should be repeated several times with different letters while making sure subjects are not secretedly rehearsing the letters in the 30 seconds interval. Experiments like these were early evidence that conscious rehearsal is important for the maintenance of short-term memory and that without it short-term memory fades very quickly.

Walking through Script 1.1

Let’s walk through the script in small steps, starting with line 1:

1 text("Try to remember the following words");

Here, we see text() with the message “Try to remember the following words”. The double-quotes tell the system it is text. The formal word for text in many computer languages is string, as in: a string of characters. You can also use single quotes instead of double quotes, like text('Welcome'). We call text() a function and “Try to remember the following words” the argument of the function text(). Arguments of a function must always be enclosed in round brackets: ( and ).

The semi-colon ; at the end of a line in a script helps the system to distinguish between subsequent script statements. It is like the full-stop at the end of a sentence, which helps us by signalling that one sentence ends and the next one starts. The semi-colon may be left out, especially when each statement is on its own line as is the case here, but it is highly recommended to always add it1.

Now, let’s look at line 2:

2 //

3

4 await(5000); // 5000 ms or 5 s

This line has the await() function with the argument 5000. When await() is called like this, the computer will stop the execution of the the script for 5000 ms and then continue. Note that the number of ms is denoted as 5000 and not “5000” (or ‘5000’). That is because it is an integer number which the computer system treats differently than strings.

There is also an addition in line 2 that reads: // 5000 ms or 5 s. This is a comment, which is completely ignored by the system. It is handy to include comments as notes to oneself or others. Here, we make clear that 5000 means: 5000 ms. A // comment only runs to the end of the line. With multiple lines of comments, you must repeat the //, e.g.,

// Starting a comment

// continuing it on the next line

There is also a type of comment that spans many lines. It starts with /* and ends with */. E.g.,

//

/*

This is a comment

that spans many lines.

As many as I want really...

*/

Make sure you start with /* and end with */ exactly in that order. In SPSS, comments are indicated with * characters without the forward slash /, but leaving out these forward slashes is not allowed in JavaScript and will cause an error.

So, there are two type of comments

- Line-based, with

// - Line-spanning, with

/* */

The following two statements in the script follow exactly the same pattern, except with different arguments:

4 //

5

6 text("YHZ");

7 await(3000);

8

9 text("Now, count back in threes starting with 307: 307, 304, 301,...");

10 await(25000);

The user’s response is recorded with the line:

10 input("Write down the letters remembered","brown_peterson");

The input() function requires a label, here: “Write down the letters remembered”, and displays this with a text input field below it in which the user can type the letters. Below that is an “OK” button. The second argument, “brown_peterson”, is the name of the variable that is created to store and label whatever the subject types into the text area.

Now you may wonder: “What is happening with the subject’s answers?”. All responses, from buttons, text input controls, drop-down select lists, check boxes, etc. (formally called form controls or controls for short), will automatically be saved into your account’s data area. You can inspect these response and download the data in Excel and other formats. It is important to give meaningfull names to variables, because then you will more easily remember what the values in the data tables in your account mean.

If you don’t give a name, the subject’s input will be saved under a automatically generated name such as “input_1”. In a small experiment this presents no problems, but when your experiment collects a lot of data mistakes are easily made. It is therefore highly recommended to find meaningful names for all recorded data.

The last statements show a ‘Thank you’ text for 3 s. After this, the NeuroTask branding screen appears signaling that the experiment is over.

12 //

13

14 text("Thank you for participating!");

15 await(3000);

Script 1.2: A free recall experiment

Let’s take Script 1.1 and turn it into a free recall test with eight words. Each word is shown for 2 s, then it is removed from the screen followed by 1 s pause, after which the following word is shown.

1 //

2

3 text("Try to remember the following words");

4 await(5000); // 5000 ms or 5 s

5

6 text("glass");

7 await(2000);

8 clear();

9 await(1000);

10

11 text("chair");

12 await(2000);

13 clear();

14 await(1000);

15

16 text("train");

17 await(2000);

18 clear();

19 await(1000);

20

21 text("balloon");

22 await(2000);

23 clear();

24 await(1000);

25

26 text("horse");

27 await(2000);

28 clear();

29 await(1000);

30

31 text("curtain");

32 await(2000);

33 clear();

34 await(1000);

35

36 text("pencil");

37 await(2000);

38 clear();

39 await(1000);

40

41 text("baker");

42 await(2000);

43 clear();

44 await(1000);

45

46 text("Now, count back in threes starting with 307: 307, 304, 301,...");

47 await(20000);

48

49 largeinput("Write down the words remembered","words_remembered");

50

51 text("Thank you for participating!");

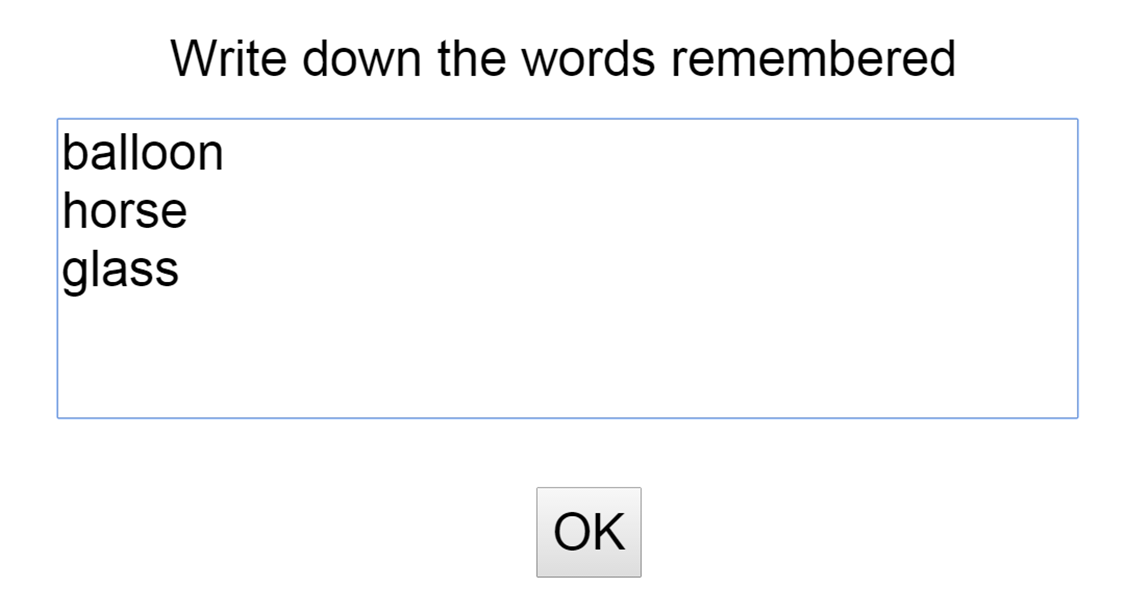

We are introducing a new function here: clear(), which removes the current text from the screen, i.e., clearing it. For the rest, it is highly similar to Script 1.1. A small difference between Scripts 2 and 1 is that we are here using largeinput() instead of input(). The difference is that largeinput() gives a large text area of about five rows in which the subject can type the responses, whereas input() gives just a single line text field, which may feel cramped when typing up to eight words:

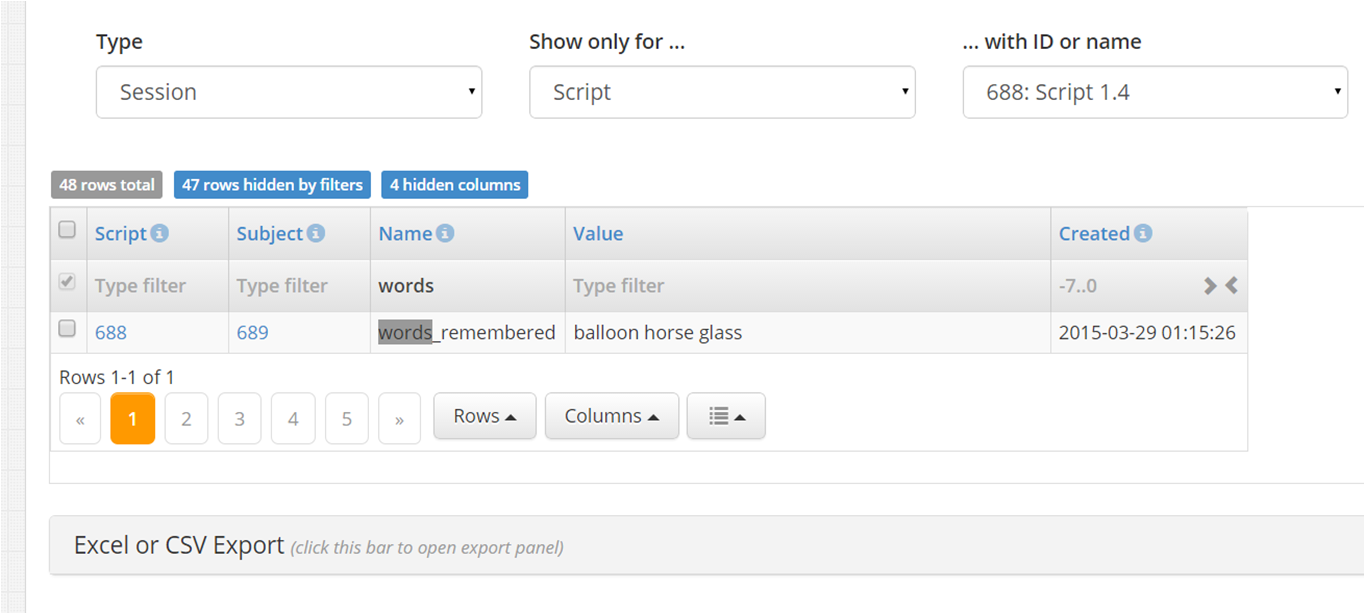

If your subjects would do this task online, you would see their answers, exactly as they typed it in, under the label “words_remembered” in the data area of this experiment script:

Perhaps, we should here point out why we used an underscore in "words_remembered" and not a space. The reason is that the names of variables in JavaScript may not contain spaces and words_remembered is used like a variable in NeuroTask. An underscore is often used instead of a space.

Now, let’s simplify this script by introducting the concepts of array and for loop.

Script 1.3: A shorter script with a for loop

There is nothing wrong with Script 1.2, but some might find it a bit long and others may notice that it is tedious if you decided to increase the presentation time from 2000 to say 3200 ms: all times must be adjusted. Especially, in large scripts it is easy to skip one by mistake.

Whenever there is a highly repetitive pattern in a script, it is a good idea to rewrite it using a so called loop. Take a look at the rewritten script:

1 var i;

2 var words = ['glass', 'chair', 'train', 'balloon',

3 'horse', 'curtain', 'pencil', 'baker'];

4

5 text("Try to remember the following words");

6 await(5000); // 5000 ms or 5 s

7

8 for (i = 0; i < words.length; i = i + 1)

9 {

10 text(words[i]);

11 await(2000);

12 clear();

13 await(1000);

14 }

15

16 text("Now, count back in threes starting with 307: 307, 304, 301,...");

17 await(20000);

18

19 largeinput("Write down the words remembered","words_remembered");

20

21 text("Thank you for participating!");

22 await(3000);

Variables

First, you may notice the use of the word var , which stands for variable. The statement var i tells the system that we want to store some data and require memory space to do this. We also want to name the variable. This is called declaring a variable. It is much like hiring a storage unit to store some surplus furniture or other stuff and giving it a name so you can easily identify it. Now you can put something (a value) in the box (variable). When you then later need it, you will always have access to the contents (value) of the box (variable). Variable names in JavaScript may contain numbers and underscores (i.e., the _ character), but they may not start with a number (but can start with an underscore). They are case-sensitive, meaning that in JavaScript variables word, Word, WORD are considered three completely different variables and not for example spelling variations of the same variable.

White space

In most places in scripts, you may insert arbitrary white space (spaces, tabs, newlines) almost anywhere, which can be useful if you want to make the layout of your scripts more legible. In the scripts, so far we have used empty lines to great groupings to help see the structure of the script. These empty lines are completely ingored by the computer system, as is most other white space.

Assigning values to variables

The first variable in the script has a very short name, it is called i. We will use i to count the number of words we are going to present on the screen, starting with 0 rather than 1.

The next line is more complex and has a another variable, which we have called words. The variable words is immediately given a value in the form of an array of strings, which correspond to the stimulus words in Script 1.2. The value of the variable words is set using the equal sign =. So, i = 0 means: “Give i the value 0.”

You can also assign the result of some calculation to a variable. For example, when you do

i = 60*24;

the system would first calculate the result of the expression 60*24, meaning 60 times 24, which is equal to 1440 and assign that value to i. So, the above statement is equivalent to

i = 1440;

You can also use the value of a variable on the right-hand side of an assignmnet, like this

minutes = 60;

hours = 24;

i = minutes * hours;

Again, i would be 1440 after these lines had been processed. In Script 1.3 we use the value of i on the right-hand side, add 1 to its current value, and assign the result to i, overwriting its current value:

i = i + 1;

So, if i was 0 at before the assignment it is 0 + 1, or 1, after the assignment. This is one way to increase the value of i by 1. You could also decrease with 2,

i = i - 1;

or multiply it with two

i = 2*i;

Arrays

An array in JavaScript is a type of list that can be compared to not just one storage unit, but a whole row of them. These units (usually called elements) are number, starting at 0 (and not at 1). This is automatic and cannot be changed. All elements of an array must be separated by commas. To indicate to the system that words is an array, the list of values must start with a square bracked [ and end with one too ].

So, the variable words now holds all words in your experiment, but how do we access them? As said, the elements in this array are numbered 0 to 7 and to get at element 0 we write words[0], which would give us the word “glass”.

Each array also knows its own length (i.e., number of elements) and this value is found by writing words.length. The dot . indicates that we are accessing a property of the array. Here, words.length is 8, because there are 8 words in the array.

for loops

Another new part of the script is the for loop2:

8 for (i = 0; i < words.length; i = i + 1)

9 {

10 text(words[i]);

11 await(2000);

12 clear();

13 await(1000);

14 }

In plain English this would say: “Repeat the statements between curly brackets as long as index i is less than the length of the words array, where i starts at 0 and increases with 1 after each repetition.” The length of an array can always be obtained with the length property. Here, words.length would equal 8 as the array contains 8 strings.

The for loop always has the same shape: it has a head and body. The head always looks like:

for (initialization; condition; step)

The body is the part in curly brackets {...}.

In the head, initialization sets variable i to its initial value, here i = 0.

The condition determines when to stop. In this case, if i is 8, the condition is false because words.length is 8 and the condition says i < words.length. Since 8 < 8 is not true, the statements in the body will not be executed anymore. So, processing the statements the body will continue until i equals 8.

The step part of the head of the for loop determines how the index i is changed after each repetition. In most cases, it is increased with 1 (called an increment), but sometimes it is handier to decrease it (called decrement) or change it in some other way.

It is important to know that even if for some reason you would not use part of the head, you still need to write both semi-colons. So, if you would choose to initialize the index before the loop, which is perfectly fine, you still need to put in the semi-colon, as follows:

var i = 0;

var m = words.length;

for (; i < m; i = i + 1)

{

// body

}

increment

In Javascript the expression i = i + 1 has a short-hand form that can be used instead: ++i. This is known as increment3 i. Similarly, --i equals i = i - 1 and decrements i. It does not do anything different but is simply a more concise form.

Another short-hand is that, when several var expressions follow each other, you can combine them using a comma, as follows:

var i, m = words.length;

You only need to write var once. Again, white space such as spaces and newlines is irrelevant and you may also layout this more clearly as:

var i,

m = words.length;

The whole loop would than look like

var i,

m = words.length;

for (i = 0; i < m; ++i)

{

// body

}

This is the format of the for loop that you will see most often.

Script 1.4: Even shorter scripts with getwords()

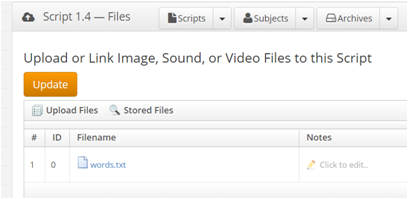

Script 1.3 is already a rather mature script that can easily be maintained. Many people, however, prefer to go one step further and separate their scripts from their stimuli. In the case of words (or sentences, sentence fragments), NeuroTask offers the function getwords() that allows you to easily achieve this. The procedure is to first make a text file that contains the stimulus words without quotes but separated by commas. For example, the file called words.txt might contain:

glass,chair,train,balloon,horse,curtain,pencil,baker

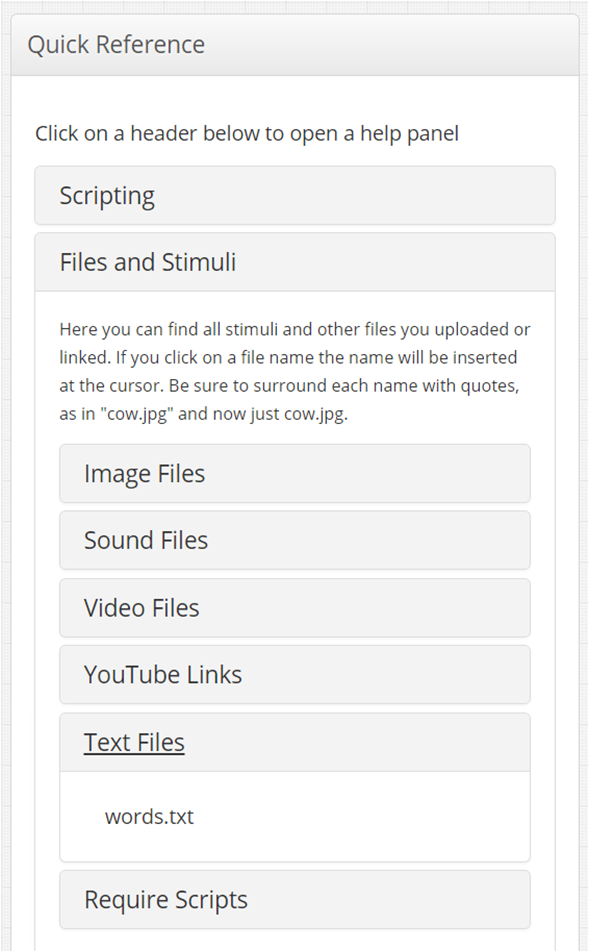

This file must be uploaded with NeuroTask’s Upload Files feature (look for the cloud symbol).

You can verify whether the upload was successful, because the filename will then appear in the menus on the right (look under Text Files). If you see it, it means you have uploaded it and that it is ready to be used with the script.

The script then becomes:

getwords(). 1 var i, words = getwords("words.txt");

2

3 text("Try to remember the following words");

4 await(5000); // 5000 ms or 5 s

5

6 for (i = 0; i < words.length; ++i)

7 {

8 text(words[i]);

9 await(2000);

10 clear();

11 await(1000);

12 }

13

14 text("Now, count back in threes starting with 307: 307, 304, 301,...");

15 await(20000);

16 largeinput("Write down the words remembered","words_remembered");

17 text("Thank you for participating!");

18 await(3000);

The gain in using this method is that at any point you can upload a file with different words. Also, the words do not need to be wrapped in quotes to make them strings. Files may be shared among scripts, which is relevant if you have several scripts that use the same stimuli, for example, for different conditions.

1.4 You have started with online experiments!

Even though the scripts in this chapter have been short and simple they were not trivial. The Brown-Peterson script could serve as a demonstration for students, especially if it were repeated a few times with different letter stimuli. The free recall script could be used as an excellent basis for, well, uh, free recall experiments. Both types of scripts recorded the behavior of the subjects using the input field. In the next chapter we will look at how you can record other types of behavior and measure reaction times.

- In some case, ambiguities may arise if semi-colons are left out. It is also easier often to find an error. ↩

- It is not necessary to indent the statements in the body, but it makes for more readable code and often helps to prevent errors; it is completely legal to leave out all spaces in this example.↩

- This is borrowed from the programming language C, as is much of Javascript, such as the

forloop and the way values are assigned with the expressioni = 0.↩