Seven sins of dubious discipline

Before we can put all this into practice, there are a bunch of problems that really must be faced. We’re aware that we might be a bit unpopular with some folks for saying this, because a few deeply-cherished delusions may get trodden on in the process. But fact is that if we dowsers don’t face those delusions… well, to be blunt, there won’t be any point in anything that’s done in dowsing. Yes, it really is that bad. Seriously.

The problems range across the full range of quality-issues we’ve seen earlier, but for convenience, we’ve clustered them here into what might be called the Seven Sins of Dubious Discipline.

The hype hubris

Sin #1 arises from what we might, in our more polite moments, describe as a triumph of marketing over technical expertise. (There are some other epithets for this that are rather ruder, if often rather more accurate.) Dowsing, earth-mysteries, in fact pretty much every field of study with a strong subjective element, are all plagued by a relentless pursuit of hyped-up glamour – Egypt! Atlantis! the Golden Age! – in which style takes priority over substance. “Never mind the quality, feel the width!”, to quote the tag-line from an old TV comedy…

Glamour sells, but it isn’t real. Like junk-food advertising, it promises sustenance, but never really delivers, leaving us unsatisfied and wanting more. Yet because the hype seems to be all that’s on offer – or at least all that’s easily available – we can get sucked back into it, again and again. More to the point, we trick ourselves into falling for it, time after time after time. And it’s our responsibility to learn to not do so – to recognise the hype for what it is, and move on.

Fair enough, the hype and the glamour are often the ‘hooks’ that grab our attention in the first place, gaining our interest enough to get us started. But at some point – and preferably sooner rather than later – we need to wean ourselves off the pre-digested junk-food, and get down to the real meat of the matter.

It’s not just the quality of our own work that’s at risk here, because there’s also a darker side to this. It’s not only that those who do the ‘boring’ detail-work, often for decades, have no way to publish their results: we’ve seen all too many cases where they’ve been misused, plagiarised, derided, then ignored, in a subtle yet singularly nasty form of ‘life-theft’. When rip-off artists are rewarded handsomely for taking us all for a ride, whilst ‘the little people’ who’ve been stolen from are actively penalised, there’s no incentive to do real work. When hype is allowed to masquerade as reality, quality suffers, for everyone.

In short, to use the old advertising metaphor, the sizzle ain’t the sausage: the hype can sometimes have a useful role to play, but in itself it isn’t real. So when someone tries to sell you the sizzle, look for the sausage: if the substance isn’t there, it’s time to walk away.

Arises from:

- blurring between Artist exuberance and Mystic belief / belonging

Resolve by:

- go to Scientist mode to check facts and sources

- cross-check in Magician mode by questing and testing usefulness of the ideas and assertions

The Golden-Age game

Sin #2 has its source in what we might call ‘a bizarre blend of super-science and super-religion’. The idea is that somewhere in the distant past – you pick when and where, there’s plenty to choose from – there was just one culture, one civilisation, one faith or whatever, with a special elite class of priest-scientists, separate from mere ordinary mortals, who somehow ‘knew it all’. They’d created the perfect utopia, which is ready and waiting for us now, if only we can find the way…

It’s a lovely dream, perhaps. Yet that’s all it is: a lovely dream. And in most cases its hidden purpose is to distract attention from our real responsibilities in the here-and-now. Which is why, if we’re not careful, chasing that dream can become a serious sin…

There’s no doubt that there is value in the quest for the ‘Golden Age’. The hope that there can even be such a place – either in the outer world, or within ourselves – is a crucial, essential driver for personal and social change. Yet we need to balance that quest with realism, and with a great deal more honesty and self-honesty than the hype-ridden hagiography of this field will usually allow.

What’s going on here is indeed about ‘super-science and super-religion’ – or more accurately a muddled blurring between the modes of the Scientist and the Mystic. The latter needs, above all, to believe in something, deeply, passionately: that’s its role. The Scientist needs concrete facts: that’s its role, too. But in the Golden Age Game, beliefs are treated as fact, and facts are filtered to fit in with the assumptions of the belief. Neither mode is used correctly; and whenever any kind of challenge occurs in one mode, the game jumps across to the other mode whilst still purporting to use the first mode’s rules. It is fact because I believe it to be true; since it is fact, it is therefore true, hence must be believed by all. Round and round the garden we go: no checks, no balances, no questions – and no question of usefulness, either. And behind it, all too often, a subtle unacknowledged arrogance: we followers of the Golden Age are also, by definition, members of that special elite, the ‘Chosen Ones’, whilst all other ‘unbelievers’ are not…

When we do check those claims against real-world analogues, such as Australian aboriginals, or the Amazonian peoples, it’s true we do often find a deep knowledge that can be far outside of what’s known in mainstream ‘techno-scientific’ culture – which is why drug-companies and others fund expeditions to raid and, bluntly, steal as much of that knowledge as they can. Yet that knowledge is also highly contextual – in other words, it lives as much in the Magician mode as the Scientist or Mystic – and always derives in part from the personal experience of the Artist mode. And though the respective lore may well have been passed down through an unbroken line of elders or grandmothers – who may well guard that knowledge with care, for reasons of health and safety if nothing else - there’s no real evidence for anything resembling the Golden Age’s beloved priesthood-elites. Just ordinary people, living their lives in their own particular way, with their own particular, peculiar responsibilities. Just like us, in fact.

The ‘truths’ of the Scientist and Mystic have no meaning on their own – and especially not when they’re mangled in Golden Age myths. To reach anything that anyone can use, they need to be balanced with the Magician’s awareness of appropriateness. And as dowsers we can also use the Artist mode to find more from the landscape than could be learned from a half-imaginary translation of some half-invented ‘ancient scroll’.

So whilst no dowser would doubt that there are real mysteries yet to be explored, the Golden-Age Game distracts from that deeper exploration. Its purported marvels consist of little more than a handful of mysteries taken far out of their real context, contorted by clueless ‘cultural imperialism’, narcissistic nostalgia and self-centred delusions of grandeur, and blown up out of all proportion by wishful thinking, hype and hope.

More than hope, perhaps. There’s a Welsh word ‘hiraedd’ that describes this well: woefully mistranslated as ‘homesickness’, it’s more “a longing and grieving for that which is not, has never been and can never be”. We do need to respect that grief: when we look deeply into it, it hurts more than most can bear. Yet building Golden-Age myths to hide from the hurt just does not help. Take that alone-ness, that crushing sadness, and work with it to build something real instead.

There is nowhere else, no-when else to which we can run away from the perils and problems of the present. If it can be said to exist at all, the only possible Golden Age we can experience exists in what we create, here, and now

Arises from:

- blurring between Mystic mode (belief, and desire for sense of belonging to something ‘special and different’) and Scientist mode (beliefs mistaken for facts)

Resolve by:

- maintain clear distinction between Mystic and Scientist

- balance with Magician and Artist modes to establish context, meaning and use

The newage nuisance

Sin #3 is perhaps more subtle, yet certainly no less of a problem in practice, because where the Golden Age Game is careless in its use of the Scientist and Mystic modes, the Newage Nuisance plays fast and loose with them all…

Although it can take almost any form, in essence it’s a dilettante ‘disneyfication’ of discipline itself – a shallow over-simplification of everything, combined with a wilful, sometimes deliberate and often near-obsessive avoidance of any kind of discipline. The term ‘newage’ rhymes with ‘sewage’, ‘the discarded remnant of what was once nutritious’ – and its stench pervades pretty much every area that purports to be ‘New Age’.

Though there are some strong links with Sin #7, inadequate management of the skills-learning process (see Lost in the learning labyrinth), newage is typified by arbitrary jumps between the distinct forms of ‘truth’ in art, spirituality, science and magic. At its simplest and most forgivable level, it’ll often occur when an overdose of enthusiasm overrides sense and self-honesty – such as in the feeling of ‘instant mastery’ after the classic New Age-style one-weekend-workshop.

The excessive exuberance of ‘beginner’s luck’ is understandable, but the real problems start whenever there’s an unwillingness, or refusal, or fear, to let go of that feeling of ‘instant mastery’. So the next stage is the ‘workshop junkie’ – a ceaseless collection of just the ‘instant mastery’ level of every possible new skill, but with no depth, no commitment, and nothing to tie the skills together into anything that can be put to practical use.

Part of the problem - especially in New Age contexts with an overt emphasis on ‘spirituality’ – is that the Mystic mode is all about being, about inner-truth: it’s diametrically opposed to the Magician mode, which happens to be the only place where “what do we do with all this stuff?” comes into the picture. But the real core is that commitment to the discipline of a skill is what finally kills off beginner’s luck, and with it that initial delusion of ‘mastery’. From there on, for quite a long while, it feels like downhill all the way – and hard work too, with personal challenges that are often far harder still. An uncomfortable time, to say the least.

So there’s a natural tendency to try to avoid that discomfort by avoiding commitment, whilst still pretending – if only to self – that mastery has already been achieved. There’s then an inevitable desire to conceal – if only from self – the fact that mastery has not been reached… And the mechanism to do this is by playing mix-and-match between the modes: the rules of one mode are used to validate the ‘truths’ from another.

The simplest and perhaps most common example of this is actually nowhere near the New Age at all, but in the phrase ‘applied science’. Doing anything, using anything, places us in the Magician mode of outer-value, and must always be tested in those terms – such as ethics, appropriateness and so on. But the phrase ‘applied science’ implies that if we can call something ‘scientific’, the only test we need apply is outer-truth – which means it’s ‘value-free’. If something’s supposedly value-free, that absolves us from having to face any difficult doubts about ethics or effectiveness: so we then claim an unquestioned right to go right ahead and do whatever-it-is because it’s ‘true’. Therein lie all manner of interesting problems in the wider world…

Looking at the paths between the modes, you’ll see there’s at least a dozen different ways this game can go. For example, for dowsers and others whose work is anchored more in the subjective space, one such mistake is typified by a common misuse of the old slogan ‘the personal is political’: “this is true for me, therefore it must also apply to everyone else”, muddling the subjective space (‘personal’) with the objective space (‘political’). The only way we can resolve the Newage Nuisance is to be clear about which mode we’re in at all times, using the correct rules for that mode, and that mode alone – and also face the fears that drive us to be dishonest about what our skills really are.

The Newage Nuisance is the Golden Age Game writ large, covering the entire context of the space in which we work. Challenging it is never easy, given the emotions that such challenges will so often engender. Yet unless we do each face it firmly – not just in others, but even more in ourselves, in everything we do – that avoidance of discipline will inevitably render meaningless every scrap of work in that space.

Not exactly a trivial sin, then. One we definitely need to address…

Arises from:

- combination of incompetence and self-dishonesty in relation to any or all of the modes, and fear of responsibilities from commitment to a skill

Resolve by:

- be clear which mode we’re in at each moment, and use only the rules and tests for that specific mode

- be clear how and why we transition from mode to mode

- challenge and face the fears that would otherwise lead to evasion of the necessary discipline in each mode

The meaning mistake

Sin #4 occurs mainly in and around the Scientist mode, where we aim to establish outer-truth, otherwise known as ‘fact’. There are clear rules in this mode for deriving fact; the Meaning Mistake occurs whenever we’ve been careless with those rules, leading us to think we’ve established that ‘truth’ when we haven’t.

The simplest way to describe this is with a cooking metaphor: the end-results of our tests for meaning should be properly cooked, but if we’re not careful, they’ll end up half-baked, overcooked, or just plain inedible.

Interpretations go half-baked when we take ideas or information out of one context, and apply them to another without considering the implications of doing so. One form of this is what scientists describe as ‘induction’, or reasoning from the particular to the general – as in that misuse of the feminist slogan “the personal is political”, where we assume that whatever happens to us must also apply to everyone else. We then leap to conclusions without establishing the foundations for doing so – which can cause serious problems when we try to apply them in practice in the Magician mode.

Perhaps a better dowsing example would be the use of terms such as ‘frequency’, ‘vibration’, ‘radiation’ or ‘energy’ – each of which has a precise meaning in science, but in dowsing is often no more than a fairly loose metaphor. The catch is that as a metaphor, it has no definitions on which to anchor either itself or any cross-references. So if we then take the metaphor too literally – the ‘frequency’ of an imagined ‘vibration’, perhaps – we soon end up with something that’s meaningless to anyone else, and probably to ourselves as well. The moves towards standardised definitions in dowsing do help – such as the Earth Energies Group’s Encyclopaedia of Terms – but there’s no means to define meaningful values for frequencies and the like when the only possible standards reside in people’s heads. There doesn’t seem to be any way round this problem, either. Tricky…

Interpretations risk going overcooked whenever we skip a step in the tests, or ignore warnings from the context that we’re looking in the wrong way or at the wrong place. It’s the right overall approach – deduction, or reasoning from the general to the particular, rather than induction – but even a single missed step can soon take the reasoning so far sideways as to invalidate the lot.

Deduction works by narrowing scope, narrowing the range of choices. In formal scientific experimentation, we’re supposed to change only one parameter at a time, to ensure that we don’t accidentally skip a step and narrow the scope inappropriately. But if we don’t know what all the parameters are, it’s all too easy to change more than one as we change the conditions of the experiment. A lot more than one parameter, sometimes… And as soon as we do so, we go overcooked.

For dowsers, one essential defence against overcooking is to include an ‘Idiot’ response in the instrument’s vocabulary. By that, as we described back in Know your instrument, we mean some kind of dowsing-response that is different to those for neutral, Yes, No, or any of the directional responses, and which indicates that the dowsing-question – whatever it is – can’t be answered in any meaningful way by Yes or No or suchlike. “Un-ask the question” is what the ‘Idiot’ response really means.

To give a really simple example, how would your pendulum respond to a double-question such as “Should I go left or right?”, or a double-negative such as “Is this not the right way to go?” The pendulum’s usual yes-or-no answers can’t make any sense here – so you’ll need another kind of response to warn you of that. That type of response is also helpful in providing feedback to improve the skill in developing questions that can be answered meaningfully just by Yes or No – and as any scientist knows, the hardest part of the discipline is designing the right questions for an experiment to answer.

So if we’re not careful, we can find ourselves in the half-bakery, or with our questing overcooked. Worse, we can easily do both at once – which gives results that really are inedible. Courtesy of the Newage Nuisance, the New Age fields are riddled with it – and it doesn’t exactly help that the incompetence is then glossed over with hype (Sin #1) or some kind of golden-age myth (Sin #2). Sadly, the dowsing disciplines can be far from immune from this problem, too.

One useful hint comes from what Edward de Bono describes as his ‘First Law of Thinking’: “proof is often no more than a lack of imagination”. (There’s also a rather more forceful version which asserts that “certainty comes only from a feeble imagination”…) The problem here is that, in itself, the Scientist mode doesn’t have any imagination: it just follows the rules. So we need to be able to dive into one of the ‘value’ modes – usually the Artist, but also the Magician – to collect new ideas to play with, and bring them back for the Scientist to test. We do have to remember to distinguish between the new ideas – the imagination – and facts – the results of tests – but with care it does work well. This is just as true in the sciences, too: Beveridge’s classic The Art of Scientific Investigation talks about the use of chance, of intuition, of dreams, and the hazards and limitations of reason – “the origin of discoveries is beyond the reach of reason”, he says.

What won’t help here is the Mystic mode: in fact it can cause the Meaning Mistake, because it treats its beliefs as facts – taking them as true ‘on faith’, so to speak. Muddled ideas about ‘spirituality’ can easily lead to the Newage Nuisance; but when self-styled ‘scientists’ start treating their beliefs as fact, they end up with a bizarre, aggressive pseudo-religion called ‘scientism’ that can be a real nuisance for anyone working in the subjective space.

As with the ‘must-be mistake’, another warning-sign of potential inedibility is any use of a phrase such as “it’s obvious” or “of course it’s the same as…” – because they usually mean that a key step or test has been skipped (‘obvious’), or a simile has been mistaken for fact.

But the only true protection against the Meaning Mistake is to recognise that the Scientist mode has strict rules for meaning, to derive what it calls ‘fact’ – and we cannot be careless with those rules if we want our work to be meaningful in that mode. We can go off briefly to other modes to gather new ideas to test: but in the Scientist mode itself, there’s no middle ground – either something is fact, or it isn’t.

Arises from:

- carelessness with the rules for the Scientist mode

- blurring with the Mystic mode by treating ‘scientific’ beliefs as fact

Resolve by:

- watch carefully for keyphrases such as “of course” or “it’s obvious” or “must be”, all of which indicate a high probability of meaning-mistakes

- in dowsing, include an ‘Idiot’ or ‘un-ask the question’ response in the vocabulary to reduce the risk of overcook

The possession problem

Sin #5 is somewhat different from the others, because it doesn’t arise from mistakes with the modes as such, but from another source entirely: ego. And behind that, all too often, are unacknowledged fears that can be surprisingly hard to face…

In essence, the problem is a fear of uncertainty. When the world becomes too complex for comfort, there’s a natural tendency to cling on to what we know, what we have, what we believe, and claim exclusive ownership of all such things. In short, the problem is one of possession – but in both senses of the word, both possessing and possessed. In our context here, we see this most often in two different forms:

- possession as separation – for example, the concept of a ‘sacred site’ as something separate from the rest of the landscape

- possession as possessing ‘the truth’ – evidenced in ‘religious wars’ such as the Skeptics’ tirades against dowsers and others, or ‘mainstream’ versus ‘alternative’ approaches to healing

The first trap is that neither places nor ideas are commodities to be possessed: they simply are. And whilst a notion of stewardship does work as a model for ownership of such things, possession doesn’t: it gets in the way, all the time.

The problem stems in part from a misuse of the Mystic mode. Like the Scientist, the Mystic needs certainty in the form of what it calls ‘truth’. But whilst the Scientist gets there by testing and cross-linking everything to everything else, the Mystic simply declares something to be ‘the truth’ – hence ‘to take it on faith’. To get round the problem that some things will inevitably not fit with that ‘truth’, the Mystic mode again simply declares that anything that doesn’t fit is ‘not-true’, to be ignored. It then places an explicit yet arbitrary boundary between them: hence, for example, the arbitrary separation between the ‘sacred’ and the ‘profane’ – literally ‘pro-fanum’, ‘that which is outside the temple’.

Nothing wrong with that in itself – it’s a useful tactic, as we’ve seen. The problem comes when people think that the boundary is real, that the boundary itself is ‘the truth’ – and try to possess everything inside it. The amount of emotion unleashed against ‘heresy’ – which literally translates as nothing more serious than ‘to think different’ – gives us a rather strong clue that it’s not just about ‘truth’ here… Trying to possess the belief, people end up being possessed by it – which is not a good idea.

We’ve seen some of this already in the Newage Nuisance and Golden-Age Game, of course, but what makes it even messier here is the creation of boundaries that are put up to protect the ‘possession’. Reality as a whole doesn’t have boundaries: pollution takes no notice of national borders, for example. And as dowsers it’s not just the fences and walls that get in our way when we’re tracking a line – it’s the arbitrary separation of things that’s the real problem, because it prevents us from gaining any sense of the whole.

So although it’s true that there are places that act as focal-points in some sense or other, there are no ‘sacred sites’ as such – everywhere is ‘sacred’ to someone, in some context. It’s all one continuum: creating arbitrary boundaries between the ‘sacred’ and the ‘profane’, the ‘important’ and the ‘unimportant’, will just get in the way, not only of action, but of thinking, too.

In much the same sense, ideas or theories about the past can become boundaries to our thinking, preventing us from seeing a context in any other way. ‘The past’ is subjective, not objective: we can’t go there, and there’s very little that we can test in the Scientist sense – we have no way to tell for certain what people thought, how they felt, what they believed. In a very literal sense, the past is a different country: they did indeed do things differently there, and often for very different reasons than those that would apply in the present time.

So discoveries in the present do not necessarily ‘prove’ anything about the past. We may well find interesting energies at so-called sacred-sites; we may well find extraordinary astronomical alignments and so on; yet that does not mean that any of it was planned by the purported ‘astronomer-priests’ of the Golden-Age Game. Instead, from what little we know of the cultures concerned, and from equivalent cultures in the present, it seems more likely that such things arose more from the intuition of the Artist – simply, that ‘it seemed like a good idea at the time’, and was. It’s perhaps more useful, too, to apply the Magician’s perspective – to ask “what use is it?” – than to fight over ‘truths’ that probably never existed in the first place…

There’s also an academic discipline called ‘deconstruction’ that can be useful here. Its task is to pick apart each assertion of ‘truth’, so as to surface any hidden assumptions. (Dowsers know all too well the need for this, in designing questions that can be answered meaningfully by a limited set of dowsing-responses – usually just Yes or No.) More useful still is an expanded variant called ‘causal layered analysis’ which applies the same questioning up and down the layers, from the everyday ‘litany of complaint’ down to the deep myths and core-beliefs. The aim in both cases is to identify notions and worldviews that are somehow ‘privileged’ – assumed to be fact, but without any actual questioning to verify it as fact.

It then becomes useful – if sometimes embarrassing – to ask what worldviews and assumptions tend to be ‘privileged’ in dowsing, in earth-mysteries and in the ‘alternative’ fields in general. The Golden-Age Game is one obvious example, but there are plenty of others – such as the tendency to regard anything supposedly ‘alternative’ as inherently better than anything ‘mainstream’.

So another potent source for the Possession Problem is that, in part because of the nature of the Mystic mode, each group and enclave will tend to create, and enforce, its own orthodoxy, its own ‘official version’ of ‘the truth’ – frequently deriding anything and anyone else as ‘the lunatic fringe’. Archaeology has a long history of this, for example; likewise medicine, in fact pretty much every discipline with a strong subjective base which it needs to present as ‘the truth’.

What’s interesting, too, is the process by which yesterday’s ‘heresy’ so often becomes today’s orthodoxy, and onward to tomorrow’s passé ‘primitive beliefs’. As Thomas Kuhn showed in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, it’s something of a truism that science will progress mainly by the death of senior scientists – especially those who’ve had a huge personal investment in some particular theory, and will permit change only ‘over my dead body’, in an all too literal sense… In other words, the Possession Problem again.

The best way round this, perhaps, is to take the long view: ‘truth’ changes over time, but quality is real, and lasts forever. And if anyone tells you they own ‘the truth’ about anything, be wary: it’s almost certainly a problem of possession.

Arises from:

- excess of certainty, or fear of uncertainty, leading to inappropriate use of the Mystic mode

Resolve by:

- balance with the Magician mode concept that beliefs are tools, not absolutes

- also use the Magician mode to ask “what use is it?” rather than only “is it true?”

- watch for arbitrary boundaries between ‘sacred’ and ‘profane’, between ‘mine’ and ‘not-mine’ and so on, and use insights from the Artist mode to create bridges across the boundaries

- use deconstruction and similar tactics to challenge possession in all its forms – especially in yourself

The reality risk

Sin #6 extends the Meaning Mistake in a rather different direction, but in some ways an even more dangerous one. The problem arises from what at first seems an innocuous question: “is it real or imaginary?” But the question in itself indicates that someone doesn’t understand what’s going on here. In the subjective space – in pretty much any space, really – it’s not a question of ‘real or imaginary’, but ‘real and imaginary’ – always both, always together. Yet the way some people approach this issue could best be described as a health-and-safety hazard akin to playing with matches in a firework factory… a sin indeed…

There’s a huge hazard here – and like every other hazard, we can’t evade it simply by pretending that it isn’t there. Time and again we see people playing a bizarre yet potentially lethal game, invoking ‘energies’, getting wildly excited about them, then walking away without doing any kind of ‘tidying up’, on the assumption that it’s perfectly safe to do so because those energies are “only imaginary”. That it’s nothing like as simple as that is illustrated by the fact that many of the would-be ‘earth-healers’ we’ve known have died relatively young, in most cases from some very nasty cancers. Sorry, folks, but this is not a New Age game: and the sooner people wake up to this fact, the better for all…

We perhaps need to hammer this point home: if you imagine something, it’s real – with all of the risks and hazards that that implies.

At the personal level, we’ll see some of the same concerns as in the Possession Problem: people thinking they possess some idea, some imagining, but end up becoming ‘possessed’ by it, allowing it to drive their life without – though sometimes, powerless, with – conscious awareness of what’s going on. The magical traditions provide plenty of warnings on the dangers here, and also what to do about them: Dion Fortune’s classic Psychic Self-Defence may seem a little dated these days, but it’s still an essential reference for anyone working in this space.

Perhaps a simpler example, though, is the actor who takes on a character, Method-style, and then can’t get out of character at the end of the play. Again, the theatre tradition has its own tactics for dealing with this: Keith Johnstone’s Impro is a useful reference here, particularly the section on Masks and trance. One of his key points, for example, is that it’s essential not to treat a Mask as an inanimate object: each will have its own ‘vocabulary’ of movements and styles and actions which will tend to be taken on by any actor who wears it. In that sense, to work with a Mask, we have to enter into relationship with it – and recognise that in that relationship the Mask has choices too.

Yet everything is a Mask, a ‘per-sona’ – literally ‘that through which I sound’. A dowsing-instrument is a Mask: as we’ve seen, it too will have its own vocabulary of responses, and every experienced dowser will know that sense of needing to be ‘in relationship’ with the instrument in order to get it to work well. Likewise every place is a Mask, with its own vocabulary, its own expressions, its own choices: and sometimes we can take on those characteristics without being aware that we’re doing so.

What we may perceive as ‘imaginary entities’ at a place are also just as real – with everything that that implies. Take the example of ‘faery’: to those of a New Age bent, this will no doubt bring up the cute image of the Cottingley characters, or Findhorn-style devas, flickering energies like little fluttery things at the bottom of the garden. If so, remember also that in the Irish tradition, the fairies standing guard in front of the hollow hills aren’t like that at all: they’re seven feet tall with, yes, long pointy ears – but also with long pointy teeth. They don’t feel pain, it’s said – but they’re fascinated that you do… In short, be very careful what you ask for, for you may just get what you ask…

The same applies with the rather more active ‘energies’ that can be associated with some types of site. Referred to as ‘guardians’, they’ve even been known to follow people home, so to speak, in some cases causing absolute havoc with poltergeist-type effects, or worse. The archaeologist Dr Anne Ross has described one such incident, for example, which was linked to some ancient stone heads she’d found during a dig near Hexham in Yorkshire: the results were very disturbing for all concerned, and it took a lot of work – including a full-blown exorcism – before the incursions ended and were put to rest. So yes, all imaginary, it seems – yet also all too real, in a functional and even physical sense.

Legends and so on will often warn us of potential risks at a place: we need to be aware of this, respect it, and take appropriate action or apply appropriate protection where necessary. As dowsers we should also make use of those ‘side-feelings’ from the Artist mode to warn us of risks arising whilst we’re working: if we get a sudden sense that we should stop working, it’s best to do just that, and quickly. And for the same reason it’s wise to take a leaf out of the Magician’s book, and formally ‘close the site’ after a session: to quote an old science joke, “please leave this decontamination room as you would wish to find it!”

In this kind of context, ‘sins’ such as the Hype Hubris, the Golden-Age Game and the Newage Nuisance are not just a problem: they can be downright dangerous for everyone concerned. On the one side, people can become so deluded in their own self-importance that they can be blithely unaware of the real risks involved in these fields; on the other, there can be a fall back to uncontrolled panic when reality finally breaks through. It’s not a pretty picture: once again, as with every other skill in a hazard-laden space, this is not a place where childish minds can be let loose to play…

Perhaps the safest approach here would be a Fortean one. Way back at the turn of the previous century, Charles Fort was a journalist who collected information about events that didn’t fit with anyone’s theories – ‘the book of the damned’, he called it. Present-day Forteans follow a similar line, yet extend it with a demanding discipline: they document every description of each incident of ‘the damned’ – fairies, flying saucers, showers of frogs and fishes, you name it – exactly at face-value; but they don’t interpret. In other words, they keep it strictly in the Artist and Magician modes; the Scientist and the Mystic can perhaps come in later, but they don’t belong at all in that early exploratory stage. They work with the weird intersection of the imaginary and the real, accepting it for what it is – and reduce the risks accordingly.

Whichever way we look at it, the real is imaginary; the imaginary is real. If you ever forget that fact, you may be putting yourself – and others – at very real risk. You have been warned!

Arises from:

- failure to grasp the deeper complexities – and dangers – of the subjective space

Resolve by:

- reduce the risk with a Fortean approach, recognising that everything is real and imaginary at the same time

- recognise the hazards, and use safety-procedures such as the ‘can I? may I? am I ready?’ checklist, or the magical-tradition ritual of formally opening and closing the circle

- when dowsing, use the ‘side-feelings’ to warn of potential dangers, or changes that imply that something may be at risk

Lost in the learning labyrinth

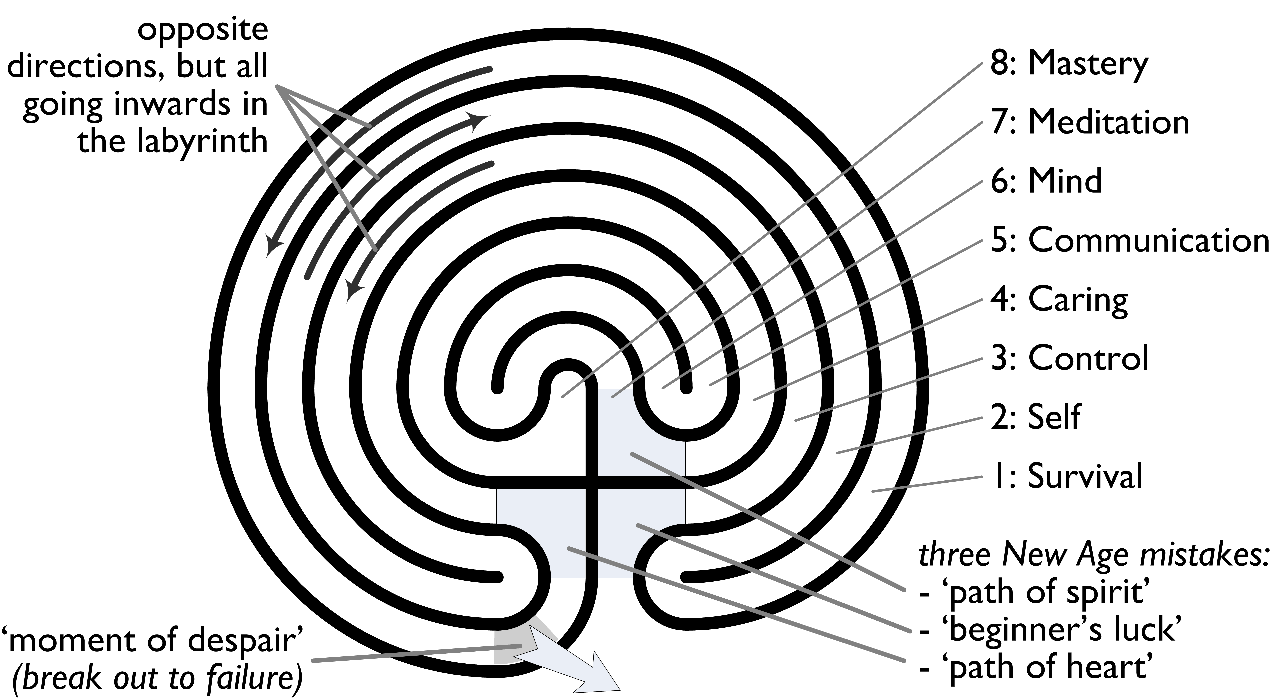

Sin #7 doesn’t come from misuse of the modes, but mistakes in the skills-learning process – and all of these mistakes are illustrated well in the labyrinth-model we introduced back in Round the bend). The problem here is that although there’s only one path, and may seem straightforward enough, it’s still all too easy to get lost in the labyrinth…

One of the classic New Age mistakes happens right at the start of the learning-process – confusing ‘beginner’s luck’ with real mastery, as we’ve seen in Sin #3, the Newage Nuisance. If we look at the labyrinth layout, though, we’ll see that this is just the first of three places where anyone on the path will seem to be very close to the centre. The other two are at the beginnings of circuit 4, ‘caring’, and of circuit 7, ‘meditation’ – which, in their guise as ‘the path of heart’ and ‘the path of spirit’ respectively, are likewise classic sources for New Age delusions of ‘instant mastery’. There’s only one path through the labyrinth – and we can’t skip any of it if we want to achieve real mastery of a skill.

We’ve seen earlier that we start out at ‘control’ – training, in fact – and that it gets worse for quite a while as soon as we make the turn outward to circuit 2, ‘self’. Note too that the same pattern repeats further in, with the double-jump from ‘survival’ to ‘caring’ to ‘meditation’, and then back outward again to ‘mind’ and ‘communication’, it may seem hard to let go from the sense of quiet certainty at the end of ‘meditation’ and moving outward to ‘mind’.

More on the skills-labyrinth

Try tracing the path with your fingertips, from the opening at ‘beginner’s luck’ to the end at ‘mastery’. Notice how hard it is to stay on track; notice also the sheer centrifugal force that seems to want to hurl you out of the labyrinth at that bleak moment of despair, at the end of the ‘survival’ circuit, when you realise that you’re not only further out than everyone else in the skill, but worse than when you first started. If you give up at that point, you’re likely to lose everything that you’ve learned; but if you can make it round the curve, through the ‘dark night of the soul’, you’ll never lose it – it’s that close. (Though notice too that from sheer relief you’ll be more prone there to the second of the New Age mistakes, the delusion that the start of the ‘path of heart’ is the centre – watch out, because there’s still a long way to go…)

Another confusion is that ‘the dark night of the soul’ is the only place in the whole labyrinth where you walk shoulder-to-shoulder with someone else on another circuit who’s going the same way. (That the other side of that match is the exuberance of beginner’s luck’ just makes the agony of the ‘dark night’ even worse…) Everywhere else in the labyrinth, people going the same way will always seem to be going in opposite directions. Which provides plenty of opportunity for error in the skills-learning process, especially when learning in parallel with others…

So although working on one’s own can be lonely, the labyrinth shows there are some subtle problems from working in groups. Collaboration is important during the later interpretation phase, to build a ‘hologram’ of the results by viewing the results from many different perspectives. But in the exploratory stage of dowsing fieldwork there can be a real problem of mutual interference from clashing expectations, and from the Possession Problem’s all-too-natural tendency to ‘help’ others by insisting “that’s wrong – you must do it this way!” Not a sin as such, but something of which to be wary.

A final trap is that the whole process is recursive: we’re each traversing not just one labyrinth, but an infinite number of them, layers within layers, all at the same time. The moment you hit mastery at one level may well be the same moment that you hit the despair of the ‘dark night’ on another – and vice versa, of course. There’s no avoiding this: you can only win if you commit to the game, and the only escape-route would cause you to lose the lot. So despite the roller-coaster ride, the wild twists and turns, the labyrinth shows there’s just one simple way to improve the skill, and the quality of the work. To stay un-lost in the learning-labyrinth, all you have to do is to keep going, keep going, one step at a time.

Arises from:

- failure to understand and accept the process of learning new skills

Resolve by:

- use the labyrinth as a study-guide for potential problems, and act on any issues accordingly

Cleansing the sins

This heading might perhaps sound a bit biblical and blaming, but it’s nothing like that bad – honest! The point we’re aiming to make here is that what we’ve shown in the sections above are indeed ‘sins’, and they do indeed need to ‘cleansed’ if there’s to be any chance of lifting the quality of dowsing practice – but it might first be useful to remember what ‘sin’ actually means…

The literal translation of the word is something like ‘error’, with an extra emphasis on what would otherwise be called ‘ignorance’. So the ‘sins’ are just errors of practice that need to be fixed, mistakes that anyone can fall into – mistakes that we all fall into from time to time, to be honest about it. It’s not a big deal. It’s just that facing the ‘sins’ is what will make the difference between work that is meaningless, bluntly, and work that will have real value for you and for everyone else.

So what’s the way out? Practice, practice, self-awareness and more practice, would be the real answer – as for every discipline, in fact. Yet there are also a couple of useful hints from the two different meanings of ‘ignorance’.

The first is that sense of ‘being in ignorance’, of not knowing. Well, now you do know about each of those Seven Sins, and we’ve given some suggestions as to how to tackle each of them in practice: so you can’t claim you’re in ignorance any more, can you? (say we with a bright grin or two!)

The other sense is trickier: that of wilful ‘ignore-ance’. If you know about the problems, but deliberately choose to ignore them – and ignore the consequences too, in all probability – there’d not be much we could do to help you there. We can warn you about the sins, but we can’t cleanse your sins for you, y’see…

Your choice: it’s always your choice. Quality is a personal commitment, a personal responsibility.

And with that central point, we’ve really come to the end of all we can show you about the disciplines of dowsing, and about the practical problems of creating quality in the subjective space. All that remains now is to illustrate all of this with some examples of how we ourselves put these principles into practice in our day-to-day dowsing work.