Dowsing in ten minutes

Okay, we’ll admit it, this might take a bit more than ten minutes – but it’ll be quick and easy, anyway.

What is dowsing?

Dowsing can be found in such a wide variety of forms and with so many different uses – from water-divining to healing, from geomancy to radiesthesia, and a swathe of subtler variants such as ‘deviceless dowsing’ – that if we look only at the surface appearances it can seem a little difficult to say exactly what it is. But if we jump upward a step or two, what they all have in common is this:

- we’re sensing something (though at the moment don’t worry too much about just how or what we’re sensing…);

- we have some means to identify the location of that sensing (though ‘location’ can be a pretty broad term here…);

- we have some way – some question in mind – to derive meaning from that coincidence (‘coincide-ence’) of sensing and location;

- the whole point of all this is to put it to some use.

Take the example of the stereotype water-diviner – a gnarled old man with a gnarled old stick. The bent twig seems to be part of the process, but its real role is to make it easier both to sense the water below, and to know when he’s sensed it. When the rod goes up or down or whatever, that’s the right location. X marks the spot. it means there’s water there, he says. Which, if you dig down to the right depth, will lead you to water you can use. This isn’t a game he’s playing: there may well be livelihoods at stake, or lives, even. And if he’s running a full-scale drilling-rig on ‘no water, no pay’ – as many of the professional water-diviners do – he has another darn good reason to make sure his dowsing is good, too. Quality matters.

And let’s take another stereotyped example, the distant-healer at her desk, holding a lock of her client’s hair in one hand and waggling a pendulum with the other hand over a list of ailments and cures. A twirl of the pendulum one way means ‘Yes’, she says; the other means ‘No’; all the sensing is simplified down to just those two choices. The location here is virtual, or metaphoric: is there a match to this place in the body, this item on the list? The lock of hair helps her to maintain her focus on this specific client – the person to whom this dowsing would be of use – which is also, in its way, a kind of location in social space. Put this all together, to derive meaningful coincidence – in this case identifying the needs and concerns of the client. Or should be, anyway: the results would be meaningless, even downright dangerous, if the quality of dowsing is poor. Once again, quality matters.

Let’s jump sideways even further, to an example that at first you might not think of as dowsing: a massage therapist, pressing fingers gently but firmly along the client’s arm. The fingers themselves are the ‘dowsing instrument’ here, deriving different feelings or sensing at specific locations on the arm, or elsewhere in the client’s body. What those sensings mean to the therapist depends on the conceptual frame in use: it may be physical anatomy, acupressure points, auras, whatever – at this metaphoric level they’re all much the same. But the aim, the use here is to help the client get well, or stay well – there’s a practical purpose for all this activity. And the point, once again, is that if the quality isn’t there, there’s no point in doing the work.

These examples may seem worlds apart, but the underlying principles are exactly the same: some form of recognisable sensing; an identified location; meaningful coincidence of sensing and location; and a use or purpose for all of this.

See let’s look at how all of this works in practice.

Know your instrument

Whenever we go out dowsing on site, there’ll always be some spectator who asks “does it work, then?” But the question misses the point: it doesn’t ‘work’ as such – you do. A dowsing instrument – the rod or pendulum or picture-postcard or whatever – can make it easier to see what’s going on, but it’s not essential: the real instrument is you.

What the visible instruments do is make your own sensing more visible to you. A divining-rod springs up because your hands move slightly. The same with the sideways movements of the angle-rods – as we’ll see in a moment. And much the same with the pendulum – the old builders’ plumb-bob, or a ring on a string – swinging sideways or in circles because your hand moves slightly fore-and-aft or side to side. So there’s nothing special at all: in every case, the instrument moves because your hands move – nothing more than that.

Let’s look at angle-rods first. These act as mechanical amplifiers or indicators for small rotational movements of the wrist: move your hand a little, and the rod moves a lot, in much the same way as the handlebars do for steering a bicycle.

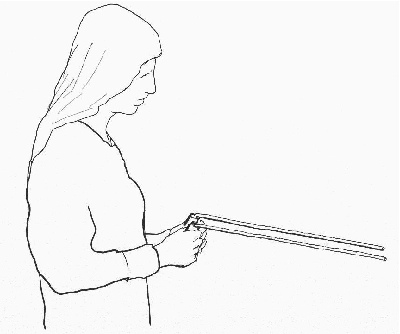

Holding angle-rods

They’re typically made out of fencing wire or an unravelled coat-hanger, bent into an L-shape. Pretty much anything goes – we’ve seen people use folding radio-aerials, or metal ‘blades’ custom-made by a blacksmith – but the mechanical criteria for angle-rods are that:

- the vertical shaft turns freely in your hand – so it can move smoothly ‘by itself’

- the horizontal arm is long enough to break ‘starting friction’ without being so long as to be a nuisance

- the horizontal arm is reasonably straight – so you can see where it’s pointing

- there’s a tight right-angle between vertical shaft and horizontal pointer – so, again, it can turn freely

- the material is light enough to hold and to turn freely, but heavy enough to not get caught in the wind

Medium-gauge fencing-wire with a horizontal arm of around twelve to eighteen inches (30-50cm) and a vertical shaft of around three to six inches (8-15cm) will satisfy those criteria well. It can also be helpful to use handles or sleeves for the vertical shaft, perhaps made from wood or cotton-reels or a discarded ball-point pen, but they’re not essential.

Some people use only a single rod: it works well as a pointer to follow a direction. But paired rods give more choice of expression – cross-over, pointer, parallel and so on – so we’ll use that in what follows.

In practical use of the rods, we’ll see wide variations in personal style; but remember that the role of the rods is to act as amplifiers for small movements of the wrists. So the mechanical criteria here are that:

- the horizontal arm needs to be able to swing freely from side to side – hence handles are useful, but not required

- the horizontal arm needs to be just below a horizontal level – if it’s too low there won’t much amplification, if it’s too high it’ll be too unstable

- the wrist needs to be able to rotate freely – the best posture for this is with your arms about body-width apart at waist-height, with the forearms roughly level with the horizontal

So, for example, we’ll often see people holding the rods with hands close together, clamped tight against the chest; but in practice it’s perhaps not a good idea. It might feel safer, perhaps, or more controlled, but for purely mechanical reasons, holding the rods in that way will make it harder to get good results. Keep things simple, keep it free and easy, to give quality a chance to come through.

The classic angle-rods response is the cross-over – also known as ‘X marks the spot’. But we really need to develop a full vocabulary of responses, to give us a broader ranger of pointers to interpretations. Some common examples include:

- cross-over – the point where the rods cross is the location

- squint (rods leaning slightly towards each other) – often used as active-neutral, such as when tracking along a line

- double-point (both rods pointing to one side) – in tracking, line bends in the direction shown by the rods

- single-point (one rod continues to point forward, the other points outward or across) – in tracking, typically implies a junction, or another line crossing at a different level

- splay (both rods pointing in opposite directions) – T-junction on a line, or dead-end

- spin (one or both rods spinning) – variously interpreted as a ‘blind spring’ (water moving up or down), or some kind of ‘energy node’

- null (both rods exactly parallel, accompanied by a ‘nothing’ feel) – passive-neutral, often implies ‘lost it’, lost the connection

As for what this means? Well, more on that in a moment. First, though, the other most common instrument, the pendulum.

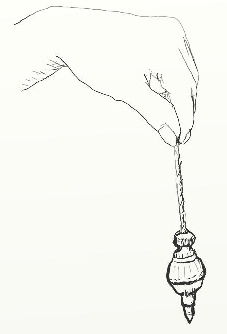

Holding a pendulum

This is a small weight suspended below the fingers, so that, again, a small side-to-side movement of your hand is made more visible. The mechanical criteria are as follows:

- the closer the weight is to symmetrical in shape, the more stable and predictable in response

- a point at the base of the weight makes it easier to see what’s going on

- the string-length should be constant – hence holding the string between finger and thumb is more reliable than draping it over a finger

- the string-length determines period of swing, and should ideally match the natural resonance of the hand- and arm-muscles – hence a typical length of around one to three inches (3-8cm)

- the weight needs to be light enough to respond quickly, but heavy enough to not be blown around by the wind

From the above, the ‘best’ pendulum is a spherical shape with a point, such as smallish version of a traditional brass builder’s plumb-bob; use a lighter one for indoor work, a heavier one on site. In principle, though, you can use whatever you like – we’ve seen people use anything from a tiny crystal to a wooden toy-soldier, from a four-pound pottery gnome to a used teabag – but note that it does tend to get harder to use the further you go from those mechanical criteria.

There’s also one mechanical criterion about usage, to do with starting-inertia. Some people use a ‘static neutral’ – in other words the pendulum indicates neutral when it’s completely still. The problem with that is that it takes time for the pendulum to ‘wake up’, in a mechanical sense – which means that you may have already moved past a point by the time there’s any visible response on the pendulum. So we usually recommend a ‘dynamic neutral’, where a small forward-and-back movement indicates neutral, because the pendulum can ‘wake up’ much more quickly.

Many people use opposite rotations to distinguish between positive and negative responses to questions – for example, clockwise means ‘Yes’, counter-clockwise means ‘No’. As with the angle-rods, though, it’s useful to build a broader vocabulary of responses, including:

- positive and negative – clockwise and counter-clockwise, as above, are typically used for this

- pointer – typically, the angle of swing indicates direction

- ‘idiot’ response, as ‘unask the question’, because the context is such that neither ‘Yes’ nor ‘No’ would make sense – a side-to-side swing is often used for this

- null, the ‘lost it’ response – a dead stop is often used to indicate this, confirmed by a ‘nothing’ feel

Whatever the instrument we use, the trick is that it should feel as if it’s moving all by itself. Just remember that it isn’t: it’s the hands that are actually doing it.

As for why the hands are moving, and what it all means – well, it’s just coincidence, really… And to make sense of that, we need to look a little more closely at ‘coincidence’.

It’s all coincidence

Dowsing is all about finding a coincidence between what you’re looking for, and where you are. The complication is that the ways we define what we’re looking for, and sometimes even where we are, may well be imaginary, in the sense we create some kind of image of them to work with. So when someone dismisses dowsing as “entirely coincidence and mostly imaginary”, we might have to sort-of agree with them, because it is indeed entirely coincide-ence and mostly image-inary.

Let’s put that in more practical terms:

- you need some way to define what you’re looking for

- you need some way to identify where you are

- you need some way to recognise the coincide-ence between them

To define what you’re looking for, the classic method is to carry a sample or ‘witness’ – a small bottle of water, perhaps, or a chunk of copper wire or drain-pipe or Roman tile or whatever the target might be. It’s easy, it’s obvious, it’s tangible, and it makes sense; it’s certainly the best approach to use when you first start dowsing. Yet oddly it’s clear that this physical sample isn’t actually required, in the way that it would be for a machine-based sensor. In fact there’s one well-known commercial set of dowsing-rods, used by maintenance crews on councils across the country, whose manual insists that whatever sample is held will be what is not found – so you find a clay drainage-pipe, for example, by not getting a response with a clay sample. Other people will use a photograph or a word or symbol as the ‘ sample’ – it’s often done that way in healing-related dowsing, for example. And for so-called ‘energy dowsing’, there’s no physical sample that we can carry: instead, we have to use some kind of imagined pattern or symbol, or look for an identifiable ‘signature’-pattern of responses.

The same applies to identifying the location. The simple way is to walk around, so that the location called ‘where I am’ is literally wherever I am – the leading edge of the leading foot is a useful marker for this. But again, this isn’t an absolute restriction: we can instead imagine ‘where I am’, on a map, a drawing, an abstract diagram or the like – hence map-dowsing and so on. It gets harder, and potentially less reliable, the further we move away from the physical realm: but there’s nothing to stop us doing so.

A classic example of this is what’s known as the Bishop’s Rule, a depth-finding technique that’s been used by water-diviners for well over a century. We start off by finding water in our usual way, with a water-sample, or a colour-coded disc, or whatever. Typically, the best spot is going to be where two water-lines cross, or spiral upward in what’s known as a ‘blind spring’. We mark that point. We then walk away from that spot, this time dowsing for the depth of the water there. At some point there should be another response. We then apply the Bishop’s Rule, which asserts that distance out is distance down: the distance away from the water-line is the depth.

We identify a ‘meaningful coincidence’ from the instrument’s responses: the rods cross, the pendulum swings in a circle, and so on. The point is that we decide beforehand what will be meaningful, and what will not – much like tuning a radio to separate out ‘signal’ (the information we want) from ‘noise’ (which is everything else).

No-one knows how any of this ‘really works’: it just does. (Or at least, with practice it does!) What we do know is that belief seems to play an important part. So here we run up against Gooch’s Paradox: things not only have to be seen to be believed, but often also have to believed to be seen. If we don’t believe that dowsing can work, we’re right – it doesn’t work. It won’t work well if we don’t pay attention to what we’re thinking; and it also often won’t work if we try too hard. Getting the balance right around that paradox is one of the trickiest parts of the skill of dowsing…

One of the other points that’s known about dowsing is that it’s similar to our other kinds of physiological perception. This differs from pure physical sensing – such as with metal-detector, for example – in that what we perceive is always an interpretation, not the thing itself; and whilst it’s good at identifying edges or other kinds of sharp change, it’s not so good with continuities or with subtle change. To give an everyday example, our eyes are very good at noticing when something flicks past in a second or so, but are not so good at spotting changes that take place over minutes or more; and when given something that is completely continuous – such as in the ‘white-out’ of a blizzard – most people will start to hallucinate quite quickly, as the eyes try to create edges where none exist at all. The same is true in dowsing. What we perceive seems to be made up of edges, but that isn’t necessarily what’s ‘really there’ – it’s just the way we perceive it.

So whilst may we talk about ‘water lines’ or ‘underground streams’, for example, what’s actually down there below is unlikely to be the subterranean equivalent of a pretty babbling brook. If we dig down, what we’re more likely to find is a band of seepage through small cracks and fissures, perhaps without even a clearly-defined cut-off between ‘stream’ and dry rock. But we’ll perceive this as a distinct line, centred on the mid-point of the seepage, perhaps with an apparent width indicating the amount of flow. In other words, what we perceive is always going to be in part ‘imaginary’, because of the way that perception creates these pre-interpretive overlays. The same especially applies to ‘energy lines’ and the like: there’s probably no direct equivalence to anything physical, but we perceive them as if they’re physical lines. We do need to remember, though, that they’re technically ‘image-inary’ – with everything that that implies in terms of conceptual quality. More on this later.

What’s the need?

There’s also what we might call ‘aspirational quality’, or ‘ethical quality’, in that need seems to be a factor in determining what works and what doesn’t. Again, we don’t know why, but it’s a common experience that results tend to be more reliable if there’s a genuine need – and especially a need on behalf of others rather than for ourselves.

Many dowsers use a checklist for need, which they use before starting any work on-site:

- Can I? – am I capable of doing the work? do I have the required skill and experience?

- May I? – do I have both the need and the permission of the place or context to do the work?

- Am I ready? – am I in the right physical and mental state to do the work?

If any of the answers is ‘No’, we should stop work straight away – otherwise the results are all but guaranteed to be unreliable.

This ‘equation of need’ also seems to be one reason why scientific-style ‘tests’ of dowsing tend to fail, or at least give ambiguous results. Members of the Skeptics Society and the like will point to such problems as ‘proof’ that dowsing ‘cannot work’, but in fact it’s an inherent fault in science, not in the dowsing. To make sense in scientific terms, we need to be able to repeat conditions exactly, and only vary one parameter at a time. But if need is part of the overall equation, we have no repeatable controls for the ‘need’ factor, and hence no way to conduct a meaningful test. Which is a problem.

Yet it’s only a problem if we depend on science for our belief. Instead, we can take a technology view, concerning ourselves not with ‘how it works’, but ‘how it can be worked’. The laws of science, it seems can never be broken, so statistically we should end up with its predicted nothing-much-ness. But whilst the ‘laws of science’ can’t be broken as such, inverse-Murphy shows us that, under the right conditions, they can be bent, locally, and sometimes a lot – which gives us the gap in which we can do our work. We just need to remember that whenever we do so, it’s Murphy that’s in charge here – with everything that that implies, too!

A more subtle concern around ‘need’ in dowsing relates to its nature as a skill. The process of developing a new skill – any skill, that is, not just dowsing – will always bring up some personal challenges around commitment to the skill itself. To get through those challenges, we have to find some way to access our own passion for the skill – a drive to improve, no matter what it takes. If we can’t find that burning ‘inner need’, our skills – and the quality of our results – may well fade away to nothing.

This applies at every stage of the process, but particularly so at that bleak point known as ‘the dark night of the soul’. To understand this better, and what to do about it, we need to go round the bend a bit – by taking a brief detour through the labyrinthine process of learning.

Round the bend

The usual view of skills-development is that it’s a linear process: we gain a steady increase in ability, each layer of training building upon those before. That seems obvious enough, yet in practice it doesn’t describe the difficulties, the uncertainties, the common feeling of ‘one step forward, two steps back’, that are so often experienced in skills-development, and which make the development of any new skill so challenging. It’s also far more than mere training: it’s the education of experience, literally ‘out-leading’ that experience from within the inner depths of each person.

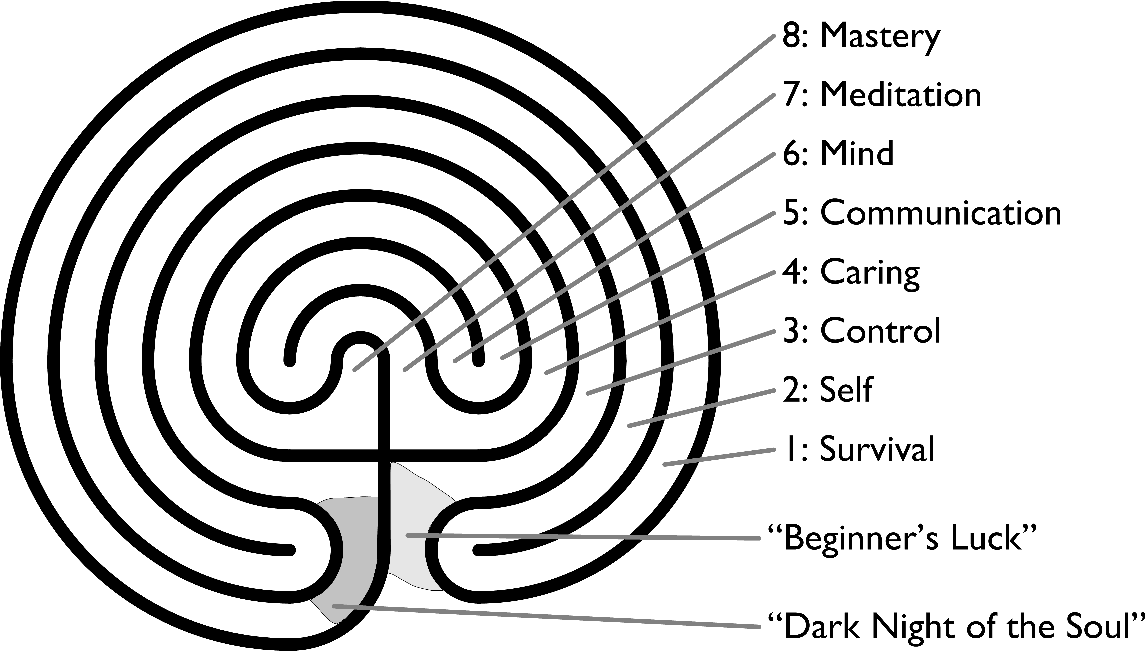

The ‘skills-labyrinth’ provides a precise metaphor that deals with these issues, in a way that’s common to every skill – so it makes the learning of any skill an easier, less stressful experience. It uses the classic single-path maze – found in many cultures around the world – to model the various stages in the personal process of learning new skills.

The skills-labyrinth

The classic labyrinth pattern is a kind of maze, but with only a single twisted path. There are no choices, no branches, no junctions – so as long as we can keep going, we will eventually get to the centre. Yet with all skills, reaching that central goal – the personal mastery of some aspect of the skill – can take a lot longer than we’d expect: and there are plenty of opportunities to get lost along the way…

The most useful version for this has seven distinct sections, in what would seem to be a linear order: survival, self, control, caring, communication, mind, meditation, mastery. But that’s not the sequence in which we experience them…

We start with ‘beginner’s luck’, the classic one-weekend-workshop ‘success’ where we succeed because we don’t know what we’re doing. There’s then a choice: either run away from the challenge – an all too common characteristic of the dilettante New Age mindset – or dive into the depths of the skill itself. If we do keep going, we move straight into ‘control’ – the limited sort-of-mastery that we can attain through training. But to go deeper, we have to go outward, to look at ‘self’, our own involvement in the skill; and then outward again, to the long, slow, painful and often barely-productive ‘survival’ stage – practice, practice, practice, often without much apparent point.

At the end of that ‘survival’ section is the worst point of all, where many people give up and abandon the skill forever. Traditionally known as ‘the dark night of the soul’ – and the exact opposite of the exuberance of ‘beginner’s luck’ – it’s often experienced the day before the exam, or the first live demonstration on-site, or some other crucial challenge. There is a way through that bleak stage: caring – a commitment to the self and to the skill itself, as much as caring in general – is the essential attribute that helps this happen. From that moment on, the skills learned so far are never lost – although as the model shows, there are a few more twists and turns to go before true mastery can be achieved!

The labyrinth model is fractal, or ‘self-similar’, in that it applies as much within each stage of skills-development as to the overall skill. As we’ll see later, in the section on Lost in the learning labyrinth, it illustrates several common mistakes, such as the tendency to cling on to the brief success of ‘beginner’s luck’. (Playing New Age dilettante is fun, of course, but nothing actually improves…) It shows how interactions between people at different stages of a skill will contribute to confusions and mistakes; it also helps explain why reliability and proficiency necessarily go down during some stages of development. And by showing that the ‘dark night of the soul’ is an inherent part of the process, it helps to reduce the risk that people will abandon their development of skill at the moment before success – at what would be great cost to themselves and their self-esteem.

Developing our skill in dowsing is the only way we’ll improve the quality of our dowsing. In turn, though, we also need to be able to identify what quality actually is – and in particular, the key distinctions between objective and subjective quality that underpin quality as a whole. That question of quality is what we need to look at next.