Practice – enhancing the senses

Enough of theory – time to get out of the armchair! So much of the dowsing space at present seems to be dominated by conversations over the Net: but whilst talk may be pleasant, on its own it rarely provides anything new. Instead, we need to engage the subtle senses of the Artist mode: and for that, getting our boots muddy, so to speak, is the only way that real change in discipline is likely to happen.

If your interest, like ours, is in archaeology and ‘earth-mysteries’, that literally means going out and getting your boots muddy: there’s a real shift that happens in spending time out in the field, dowsing in any weather, struggling with wind blowing the rods around, and rain down the back of the anorak! Or if your dowsing focus is more on healing and the like, get away from the charts and diagrams and lists for a while: your equivalent of ‘fieldwork’ would be something like massage, using the fingers and wrists and elbows to sense out the ‘musclescape’, its folds and curves, its overlays and layers, its smooth flows and locked, tangled places.

In fieldwork, we build relationship with place – whatever ‘place’ in the respective context might be. A New Age-style quick flit from one site to another won’t give space for this: it’d only deliver a few fleeting experiences, perhaps, a few brief encounters with beginner’s luck. Perhaps some sort of shallow appreciation overall, it’s true, but not much depth, nothing on which to build a real understanding. From our own experience, reaching for a deeper connection with place is like building a relationship with a skittish horse: there’s a crucial change in perspective that starts to settle in after three to six months or so – and that requires patience, a commitment to place, in all its modes and moods.

Also crucial is that most of the subtle details are visible only in the field. To see them, we need to develop ‘fieldworker’s eyes’, the fieldworker’s senses – and learn notice the differences, the edges, the subtle – or not-so-subtle – hints that things have changed.

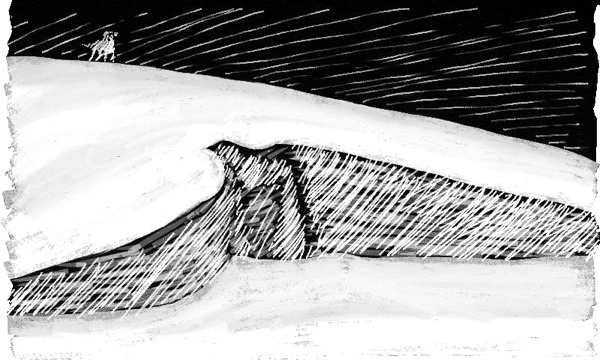

Intervisibility is another type of connection that can only be identified in the field. At Avebury stone circle, for example, the ancient mound of Silbury Hill is just visible over the skyline: anyone standing on its summit would appear to float between the nearby ridge and the distant hills. More to the point, the notches on its sides, close to the top – which, courtesy of some truly amazing early engineering, have not faded or slumped in several thousand years – line up exactly with the line of the intervening ridge. There’s no way to identify this from a map, or an air-photograph: you’d have to be there to see it.

The same is true of most ‘ley-hunting’, searching for alignments of ancient sites in the landscape. Anyone can find any number of these with a ruler dropped onto a map – a matter of considerable excitement a few decades ago – but in reality, in most cases, it’s probably ‘just coincidence’. There are real alignments to be found: but they can only be verified by cross-checking the map with what can be seen and felt in the field. John Michell, in his study of ley-type alignments in Land’s End at the tip of Cornwall, found that the key standing-stones were each exactly on the skyline from one to the next – yet usually only one could be seen in each direction, on a line ‘of rifle-barrel accuracy’ over many miles. In a dowsing sense, there’s also a distinct ‘feel’ that goes with an alignment of ancient sites that seems to have been intentional: and one that’s not will usually feel ‘flat’, or ‘dead’, or simply have no feel at all.

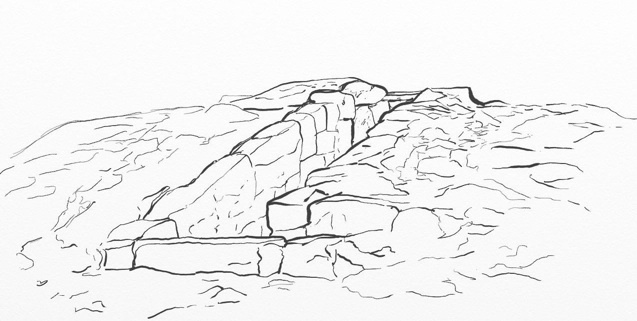

So in fieldwork we need to get out of the usual over-reliance on the head, the intellect, the ‘truth’ of the Scientist and the Mystic, and instead explore the feel of places in their own context. The journey, the process of ‘pilgrimage’ to the place, often matters as much as the destination. And we need to engage not just our eyes, but sight, sound, scent, taste, touch, synaesthesia – all of the senses, all of the elements. Notice the nature of the site itself: slow down to notice the pace of the place, its seasons, its subtleties… moss, plants, water, the sound of wind through the leaves… butterflies and birds and other small creatures scuttling around in the undergrowth…

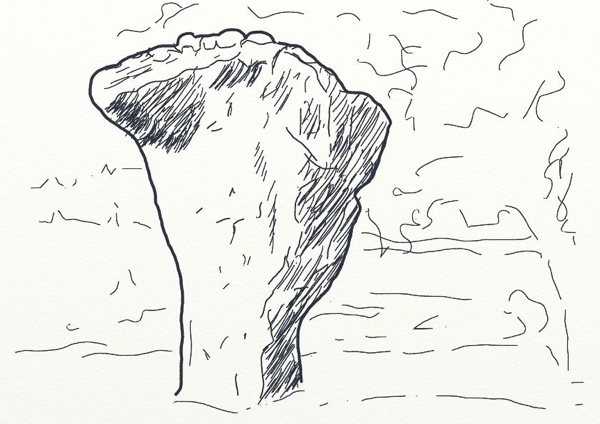

Belas Knap forecourt, with dog

It’s important, too, to watch for the Mystic mode’s tendency to create arbitrary boundaries between things, because they rarely help in the field. One such example is the imagined separation between city and country, and especially the common assumption amongst would-be pagans that ‘country is good, city is bad’ – because city-spaces do each have their own magic, even if it may be disguised deep beneath detritus, dust and diesel-fumes!

Enjoyment is important, too. Ritual and music and the like can help to engage the senses, but perhaps the wisest way is simply to have fun – laughter and merriment do matter! Having fun is also the best way to cope with fieldwork’s inevitable chaos… We do need also to watch for the tendency to be over-serious: we need a little craziness to break free of assumptions, and to jiggle the propensity to settle into the ruts of the Meaning Mistake or the Possession Problem.

To break free from the Meaning Mistake – and for that matter the Golden Age Game, or the Newage Nuisance in general – it’s essential to be able to go back to first principles, and use the Artist mode to provide hints and suggestions for suitable questions in the respective context.

This sense of the importance of small subtleties has been championed by the English charity Common Ground. For example, their Rules for Local Distinctiveness provides a useful checklist to help open an awareness of these subtleties of place. One such theme that we’ve come across before, in the discussion on the Possession Problem, is that every place is both itself and part of something greater – a locale, a district, a region of the landscape. Everything is separate, yet there also is no separation: every place contains within itself every other place.

So history is also now – the interweaving of past and present and future. Everywhere is an interaction between people and place – and sometimes the place has choices too. Sometimes the interweaving may be uneasy, a somewhat unwilling coexistence, such as the modern highway that follows the Roman road in bending around the ancient mound of Silbury Hill. Sometimes the times can collide, as with the Puritan fanatic ‘Stonekiller Robinson’, who set out to destroy all of the megaliths at nearby Avebury, and was almost killed by them instead. But what doesn’t work is an attempt to ‘freeze’ time in the present, Heritage-style – because when a place can no longer change, it dies…

Common Ground also warn us that, if we’re not careful, we can end up ‘loving a site to death’. One example would be the Anta Grande dolmen, near Almendres in central Portugal. As the name suggests, it’s big: the passage is almost forty feet long, five feet wide, more than six feet high, whilst the inside of the chamber is an astonishing twenty feet high, and the vast mound – what’s left of it – is higher still.

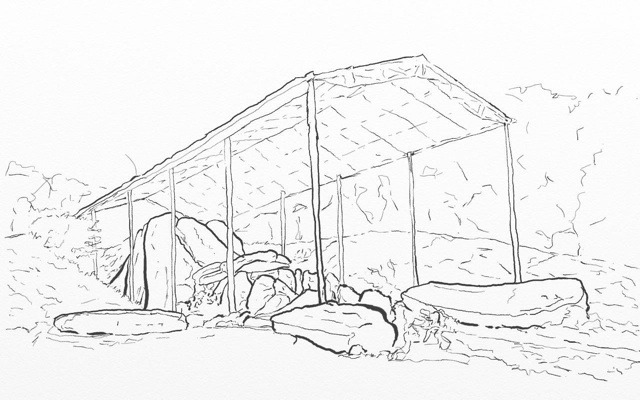

Remains of Anta Grande dolmen, Almendres, central Portugal

But after fifty years as an unmanaged tourist-site, it is, bluntly, a wreck: not much litter or graffiti, amazingly, but the passage is blocked with shoring-timbers, one of the main capstones has fallen, another fallen stone almost worn through by the footprints of countless visitors, whilst the whole is covered over by a rickety, rusting tin roof. Too popular. Too many people. Too many unrestored excavations. Ouch.

The same goes for so many places like poor old Stonehenge, of course, with something like a half a million disappointed tourists every year. Avebury is a much larger site, but even that shows many signs of struggling to cope. So we need a bit more discipline in this, too: spread the load among a much wider range of places rather than focussing only on the well-known few.

Might learn a bit more that way, too.