A question of quality

What is quality

What is quality? In the practical worlds of manufacturing and production-management, they have a definite answer to that question: quality is a kind of truth. Quality is at its best when the end-product matches exactly to some predefined standard – a reference-pattern, a rule-book, a design-specification or the like.

So there’s a whole industry built up around ‘quality’ in the business context. For straightforward commercial reasons, there’s a great deal of sense in amongst those impenetrable acronyms such as ISO-9000, Six Sigma, TQM and the rest – so if you’re interested in improving quality in general, you’ll find it worth exploring the reference-sites such as Wikipedia.

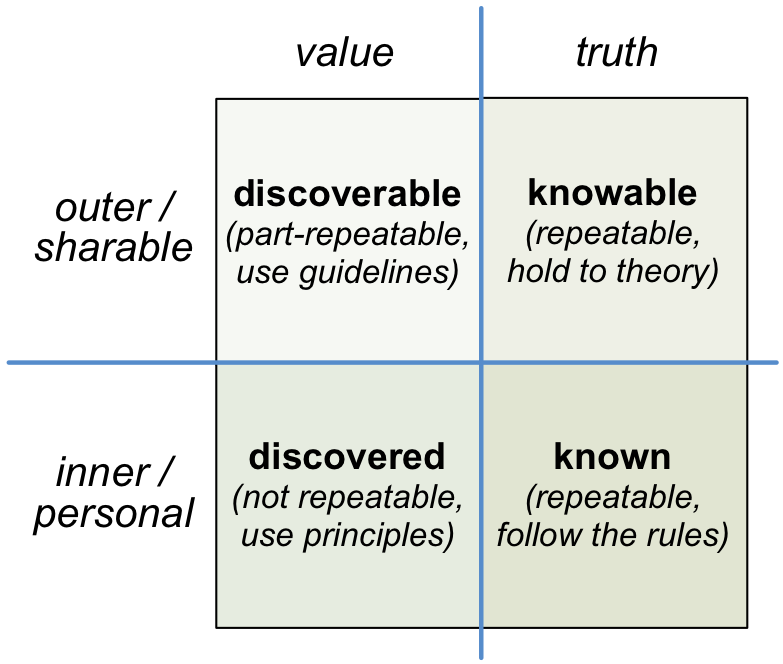

Yet in practice, quality isn’t quite as simple and straightforward as that. To illustrate this, there’s a useful model in which we partition sensemaking about quality into four domains or modes or ‘ways of working’: known, knowable, discoverable, and discovered.

Sensemaking modes

Over the next few chapters we’ll see how this kind of model applies to the disciplines of dowsing. For now, though, let’s continue exploring that notion of ‘quality’: what is it, exactly?

Predictable quality

In principle at least, that kind of quality that we see in business (sometimes described as ‘objective’ quality, though it’s actually a bit of a misnomer) should be the exact same for everyone. It expects its world to be certain, known – based on clear rules, clear patterns of cause and effect. There are procedures, work-instructions, the fast-food franchise handbook that describes ‘the one right way’ to mop the floor. Deviation from the standard is anathema: there’s no time or tolerance for anything more than training, no place for skill or personal difference. Following the rules assures a quality result; and the rules alone will suffice.

When the world becomes too complicated for that, we move on to analysis, the domain of the knowable. But there’s still always an assumption of certainty and control, that there will always be some true standard against which quality can be confirmed. So it’s here that we’ll find a focus on facts, on statistical analysis of results.

Here too we’ll see a detailed exploration of ‘best practice’ in every possible work-context - leading to outcomes that we might describe more as discoverable than ‘knowable’. Unlike the procedure-manuals, the idea of best-practice and the like does at least acknowledge that the world could perhaps be different in different places and for different people. It doesn’t assume there’s only one ‘right way to do it’: instead, it describes what’s been known to work well elsewhere, and provide some guidance as to how to adapt it to the local conditions. Which is a lot more helpful, really.

But it still doesn’t make much allowance for uncertainty, or the kind of ‘one-off’ contexts which we find ourselves dealing with so often in dowsing - those moments that are more discovered than ‘known’. For those, we need to consider more than just ‘objective’ quality: we also need to understand and maintain an appropriate balance with the subjective side of quality.

Subjective quality

As soon as we introduce skill – in fact as soon as we introduce a real person – there has to be a subjective or personal side to quality. What’s true for me – my understanding of what is quality, and what is not - may well not be true for you, and vice versa. Quality exists, quality is real, but we can’t define what it is: there’s no fixed standard against which to measure.

Instead of ‘truth’, the measure of quality here is value – what it means, how it feels, in a personal sense. There is still a kind of truth, though, that comes from respect for the material, the context itself, as typified in Michelangelo’s comment about ‘to free the sculpture from within the stone’.

There’s also a need for commitment to the skill ‘for its own sake’. Good workmanship shows good quality, clear evidence of what Robert Pirsig, in his classic Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, described as ‘gumption’. We may not be able to define beforehand what the end-result will be, yet we have a clear idea of what it would look like – and even more of what it won’t. The end-result may be finely-polished, perhaps, the work of months or years, or it may be rough-hewn, simple, assembled in a matter of moments; yet the quality – or lack of it – will usually be evident for all to see, or feel. In that sense, qualitative value both has and is its own truth.

So called ‘objective’ quality expects its world to be certain, to be repeatable, and repeatable by anyone. Subjective quality doesn’t: instead, it accepts that its world is acausal, complex, chaotic – in a word, messy. There may well be some kind of ‘self-similarity’, but nothing is ever quite the same. Yet even if there are no certainties, no fixed rules to follow, quality still exists: we don’t simply throw our hands up in the air and say “anything goes”. In the discoverable sensemaking-domain, where things still have a semblance of repeatability, we can hold to proven guidelines and ‘rules of thumb’; and in the discovered domain, the domain of ‘the unknown’, where things aren’t repeatable at all, we turn to principles that have stood the test of time – such as an awareness of the different layers in the skills-labyrinth. It works.

What also works is a different kind of sharing. Where the complicated, ‘knowable’ end of objective quality relies on supposed certainties, those who deal with worlds that are inherently uncertain – maintenance engineers, for example – will turn to ‘worst-practice’, stories about what didn’t work, and the experiments they went through to fix it. There’s also more emphasis on ‘communities of practice’, to help that sharing of stories, and assist newcomers in making sense of what’s going on in their personal quest for quality.

Quality in practice

So what does all of this mean for the disciplines of dowsing, and for other subjective skills?

The first answer is that all of the above applies: we’re always dealing with all those kinds of quality, objective and subjective, personal and sharable. Because dowsing is a personal skill, subjective quality will tend to come to the fore; but the moment we want to do anything with our results, we’d better be sure that the objective facts are there too.

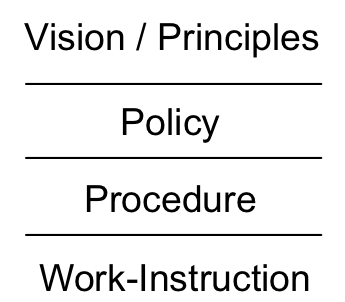

So how do we do that? One tactic is to use the same layered approach as in business quality-management:

- principles – the overall ‘guiding star’ for all of the work

- policies – ‘approaches’, decisions about how we approach changes to the work

- procedures – ‘mechanics’, decisions about how we think about the work, how we change what we do and how we do it

- work-instructions – ‘methods’, decisions about how we do the work.

Our starting point is the ‘product’ of the work – which in the case of dowsing is an opinion, about a desired or identified coincidence of what is looked for and where we are. We then use those opinions as appropriate, according to the context, but those opinions or judgements are at the core of what we do.

Layers of quality-management

In practice, we run the quality-management sequence backwards. We start from the work-instructions – for which the dowsing equivalents are things like ‘hold the rods this way’, ‘mark your location this way’, ‘use this kind of sample for this purpose’, and so on. That gives us something repeatable, a known reference-point, which will be drawn from some kind of best-practice – either from someone else, or our own.

When that work-instruction doesn’t fit any more, or doesn’t seem to work well, we move upward to the procedure, to create a new work-instruction. This is where we need that information about mechanical criteria for the instrument; likewise the more subtle ‘mechanics’ about thinking-processes and the like. We use these to assess the context, and guide a design for another way of working.

When the context changes so much that this doesn’t work either, the standard says that we need to move upward again to policy. In a dowsing sense, this is where we shift from ‘objective’ to subjective: not so much about what we do, as the way in which we approach what we do, how we make our decisions, and so on.

When appropriate care in all of this still doesn’t give us the results we need, we move all the way up to vision and principle – the final ‘guiding stars’ for everything we do. This is where that ‘equation of need’ comes in, for example: hence one useful principle in dowsing is a cultivated selflessness – “take of the fruit for others, or forebear”.

Yet this also takes us back full circle, because the ultimate root of dowsing is in precision of feeling. What exactly do we feel, at each place, at each moment, at each potential co-incidence? The instrument’s responses may be the only visible part of what we do; yet the instrument itself is just a way to externalise feelings – angle-rods as crutches for a limping intuition, if you like.

So the ‘guiding stars’ for quality in dowsing are those four principles we saw earlier:

- precision in sensing

- precision in identifying locations and facts

- precision in deriving meaning from coincide-ence of sensing and location

- precision in use of meaning – which also includes ethics.

Ultimately, what use is it? How do we identify quality in that use? For each of these, the answer lies in discipline – the four disciplines of the disciplined dowser.