What’s inside the object?

What are object’s peers?

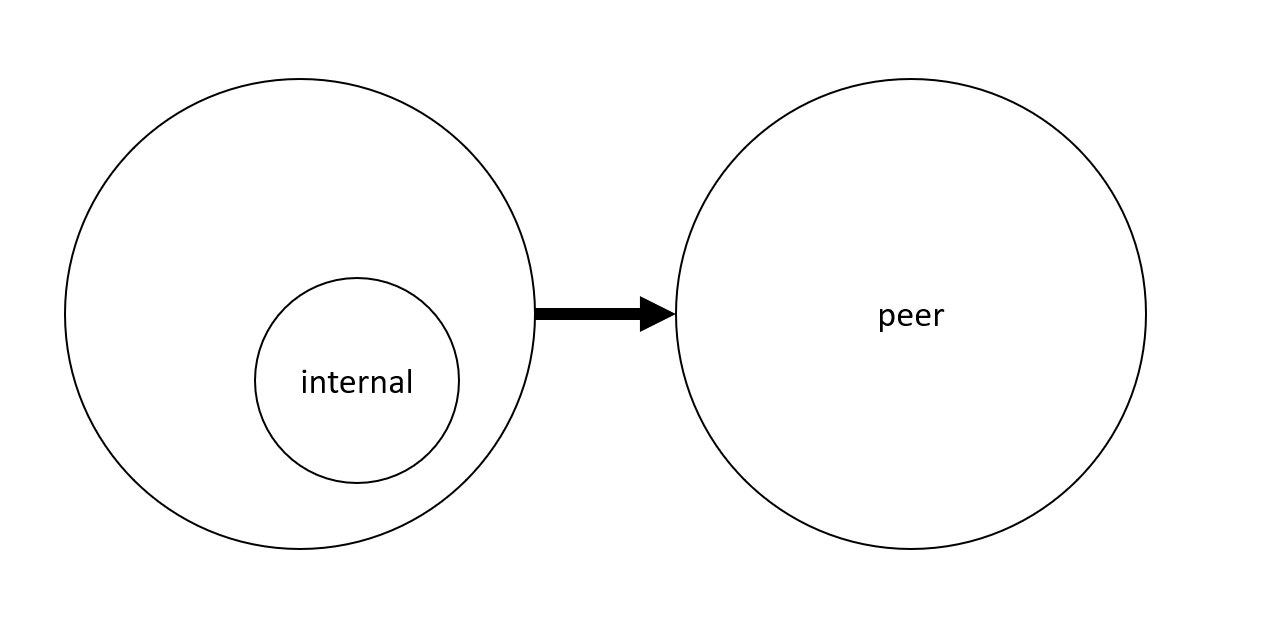

So far I talked a lot about objects being composed in a web and communicating by sending messages to each other. They work together as peers.

The name peer comes from the objects working on equal footing – there is no hierarchical relationship between peers. When two peers collaborate, none of them can be called an “owner” of the other. They are connected by one object receiving a reference to another object - its “address”.

Here’s an example

1 class Sender

2 {

3 public Sender(Recipient recipient)

4 {

5 _recipient = recipient;

6 //...

7 }

8 }

In this example, the Recipient is a peer of Sender (provided Recipient is not a value object or a data structure). The sender doesn’t know:

- the concrete type of

recipient - when

recipientwas created - by whom

recipientwas created - how long will

recipientobject live after theSenderinstance is destroyed - which other objects collaborate with

recipient

What are object’s internals?

Not every object is part of the web. I already mentioned value objects and data structures. They might be part of the public API of a class but are not its peers.

Another useful category are internals – objects created and owned by other objects, tied to the lifespans of their owners.

Internals are encapsulated inside its owner objects, hidden from the outside world. Exposing internals should be considered a rare exception rather than a rule. They are a part of why their owner objects behave the way they do, but we cannot pass our own implementation to customize that behavior. This is also why we can’t mock the internals - there is no extension point we can use. Luckily we also don’t want to. Meddling into the internals of an object would be breaking encapsulation and coupling to the things that are volatile in our design.

Internals can be sometimes passed to other objects without breaking encapsulation. Let’s take a look at this piece of code:

1 public class MessageChain

2 {

3 private IReadOnlyList<Message> _messages = new List<Message>();

4 private string _recipientAddress;

5

6 public MessageChain(string recipientAddress)

7 {

8 _recipientAddress = recipientAddress;

9 }

10

11 public void Add(string title, string body)

12 {

13 _messages.Add(new Message(_recipientAddress, title, body));

14 }

15

16 public void Send(MessageDestination destination)

17 {

18 destination.SendMany(_messages);

19 }

20 }

In this example, the _messages object is passed to the destination, but the destination doesn’t know where it got this list from, so this interaction doesn’t necessarily expose structural details of the MessageChain class.

The distinction between peers and internals was introduced by Steve Freeman and Nat Pryce in their book Growing Object-Oriented Software Guided By Tests.

Examples of internals

How to discover that an object should be an internal rather than a peer? Below, I listed several examples of categories of objects that can become internals of other objects. I hope these examples help you train the sense of identifying the internals in your design.

Primitives

Consider the following CountingObserver toy class that counts how many times it was notified and when a threshold is reached, passes that notification further:

1 class ObserverWithThreshold : Observer

2 {

3 private int _count = 0;

4 private Observer _nextObserver;

5 private int _threshold;

6

7 public ObserverWithThreshold(int threshold, Observer nextObserver)

8 {

9 _threshold = threshold;

10 _nextObserver = nextObserver;

11 }

12

13 public void Notify()

14 {

15 _count++;

16 if(_count > _threshold)

17 {

18 _count = 0;

19 _nextObserver.Notify();

20 }

21 }

22 }

The _count field is owned and maintained by a CountingObserver instance. It’s invisible outside an ObserverWithThreshold object.

An example Statement of behavior for this class could look like this:

1 [Fact] public void

2 ShouldNotifyTheNextObserverWhenItIsNotifiedMoreTimesThanTheThreshold()

3 {

4 //GIVEN

5 var nextObserver = Substitute.For<Observer>();

6 var observer = new ObserverWithThreshold(2, nextObserver);

7

8 observer.Notify();

9 observer.Notify();

10

11 //WHEN

12 observer.Notify();

13

14 //THEN

15 nextObserver.Received(1).Notify();

16 }

The current notification count is not exposed outside of the ObserverWithThreshold object. I am only passing the threshold that the notification count needs to exceed. If I really wanted, I could, instead of using an int, introduce a collaborator interface for the counter, e.g. called Counter, give it methods like Increment() and GetValue() and the pass a mock from the Statement, but for me, if all I want is counting how many times something is called, I’d rather make it a part of the class implementation to do the counting. It feels simpler if the counter is not exposed.

Value object fields

The counter from the last example was already a value, but I thought I’d mention about richer value objects.

Consider a class representing a commandline session. It allows executing commands within the scope of a working directory. An implementation of this class could look like this:

1 public class CommandlineSession

2 {

3 private AbsolutePath _workingDirectory;

4

5 public CommandlineSession(PathRoot root)

6 {

7 _workingDirectory = root.AsAbsolutePath();

8 }

9

10 public void Enter(DirectoryName dirName)

11 {

12 _workingDirectory = _workingDirectory.Append(dirName);

13 }

14

15 public void Execute(Command command)

16 {

17 command.ExecuteIn(_workingDirectory);

18 }

19 //...

20 }

This CommandlineSession class has a private field called _workingDirectory, representing the working directory of the current commandline session. Even though the initial value is based on the constructor argument, the field is managed internally from there on and only passed to a command so that it knows where to execute. An example Statement for the behavior of the CommandLineSession could look like this:

1 [Fact] public void

2 ShouldExecuteCommandInEnteredWorkingDirectory()

3 {

4 //GIVEN

5 var pathRoot = Any.Instance<PathRoot>();

6 var commandline = new CommandLineSession(pathRoot);

7 var subDirectoryLevel1 = Any,Insytance<DirectoryName>();

8 var subDirectoryLevel2 = Any,Insytance<DirectoryName>();

9 var subDirectoryLevel3 = Any,Insytance<DirectoryName>();

10 var command = Substitute.For<Command>();

11

12 commandline.Enter(subDirectoryLevel1);

13 commandline.Enter(subDirectoryLevel2);

14 commandline.Enter(subDirectoryLevel3);

15

16 //WHEN

17 commandLine.Execute(command);

18

19 //THEN

20 command.Received(1).Execute(

21 AbsolutePath.Combine(

22 pathRoot,

23 subDirectoryLevel1,

24 subDirectoryLevel2,

25 subDirectoryLevel3));

26 }

Again, I don’t have any access to the internal _workingDirectory field. I can only predict its value and create an expected value in my Statement. Note that I am not even using the same methods to combine the paths in both the Statement and the production code - while the production code is using the Append() method, my Statement is using a static Combine method on an AbsolutePath type. This shows that my Statement is oblivious to how exactly the internal state is managed by the CommandLineSession class.

Collections

Raw collections of items (like lists, hashsets, arrays etc.) aren’t typically viewed as peers. Even if I write a class that accepts a collection interface (e.g. IList in C#) as a parameter, I never mock the collection interface, but rather, use one of the built-in collections.

Here’s an example of a InMemorySessions class initializing and utilizing a collection:

1 public class InMemorySessions : Sessions

2 {

3 private Dictionary<SessionId, Session> _sessions

4 = new Dictionary<SessionId, Session>();

5 private SessionFactory _sessionFactory;

6

7 public InMemorySessions(SessionFactory sessionFactory)

8 {

9 _sessionFactory = sessionFactory;

10 }

11

12 public void StartNew(SessionId id)

13 {

14 var session = _sessionFactory.CreateNewSession(id);

15 session.Start();

16 _sessions[id] = session;

17 }

18

19 public void StopAll()

20 {

21 foreach(var session in _sessions.Values())

22 {

23 _session.Stop();

24 }

25 }

26 //...

27 }

The dictionary used here is not exposed at all to the external world. It’s only used internally. I can’t pass a mock implementation and even if I could, I’d rather leave the behavior as owned by the InMemorySessions. An example Statement for the InMemorySessions class demonstrated how the dictionary is not visible outside the class:

1 [Fact] public void

2 ShouldStopAddedSessionsWhenAskedToStopAll()

3 {

4 //GIVEN

5 var sessionFactory = Substitute.For<SessionFactory>();

6 var sessions = new InMemorySessions(sessionFactory);

7 var sessionId1 = Any.Instance<SessionId>();

8 var sessionId2 = Any.Instance<SessionId>();

9 var sessionId3 = Any.Instance<SessionId>();

10 var session1 = Substitute.For<Session>();

11 var session2 = Substitute.For<Session>();

12 var session3 = Substitute.For<Session>();

13

14 sessionFactory.CreateNewSession(sessionId1)

15 .Returns(session1);

16 sessionFactory.CreateNewSession(sessionId2)

17 .Returns(session2);

18 sessionFactory.CreateNewSession(sessionId3)

19 .Returns(session3);

20

21 sessions.StartNew(sessionId1);

22 sessions.StartNew(sessionId2);

23 sessions.StartNew(sessionId3);

24

25 //WHEN

26 sessions.StopAll();

27

28 //THEN

29 session1.Received(1).Stop();

30 session2.Received(1).Stop();

31 session3.Received(1).Stop();

32 }

Toolbox classes and objects

Toolbox classes and objects are not really abstractions of any specific problem domain, but they help make the implementation more concise, reducing the number of lines of code I have to write to get the job done. One example is a C# Regex class for regular expressions. Here’s an example of a line count calculator that utilizes a Regex instance to count the number of lines in a piece of text:

1 class LocCalculator

2 {

3 private static readonly Regex NewlineRegex

4 = new Regex(@"\r\n|\n", RegexOptions.Compiled);

5

6 public uint CountLinesIn(string content)

7 {

8 return NewlineRegex.Split(contentText).Length;

9 }

10 }

Again, I feel like the knowledge on how to split a string into several lines should belong to the LocCalculator class. I wouldn’t introduce and mock an abstraction (e.g. called a LineSplitter unless there were some kind of domain rules associated with splitting the text). An example Statement describing the behavior of the calculator would look like this:

1 [Fact] public void

2 ShouldCountLinesDelimitedByCrLf()

3 {

4 //GIVEN

5 var text = $"{Any.String()}\r\n{Any.String()}\r\n{Any.String()}";

6 var calculator = new LocCalculator();

7

8 //WHEN

9 var lineCount = calculator.CountLinesIn(text);

10

11 //THEN

12 Assert.Equal(3, lineCount);

13 }

The regular expression object is nowhere to be seen - it remains hidden as an implementation detail of the LocCalculator class.

Some third-party library classes

Below is an example that uses a C# fault injection framework, Simmy. The class decorates a real storage class and allows to configure throwing exceptions instead of talking to the storage object. The example might seem a little convoluted and the class isn’t production-ready anyway. Note that a lot of classes and methods are only used inside the class and not visible from the outside.

1 public class FaultInjectablePersonStorage : PersonStorage

2 {

3 private readonly PersonStorage _storage;

4 private readonly InjectOutcomePolicy _chaosPolicy;

5

6 public FaultInjectablePersonStorage(bool injectionEnabled, PersonStorage storage)

7 {

8 _storage = storage;

9 _chaosPolicy = MonkeyPolicy.InjectException(with =>

10 with.Fault(new Exception("thrown from exception attack!"))

11 .InjectionRate(1)

12 .EnabledWhen((context, token) => injectionEnabled)

13 );

14 }

15

16 public List<Person> GetPeople()

17 {

18 var capturedResult = _chaosPolicy.ExecuteAndCapture(() => _storage.GetPeople());

19 if (capturedResult.Outcome == OutcomeType.Failure)

20 {

21 throw capturedResult.FinalException;

22 }

23 else

24 {

25 return capturedResult.Result;

26 }

27 }

28 }

An example Statement could look like this:

1 [Fact] public void

2 ShouldReturnPeopleFromInnerInstanceWhenTheirRetrievalIsSuccessfulAndInjectionIsDi\

3 sabled()

4 {

5 //GIVEN

6 var innerStorage = Substitute.For<PersonStorage>();

7 var peopleInInnerStorage = Any.List<Person>();

8 var storage = new FaultInjectablePersonStorage(false, innerStorage);

9

10 innerStorage.GetPeople().Returns(peopleFromInnerStorage);

11

12 //WHEN

13 var result = storage.GetPeople();

14

15 //THEN

16 Assert.Equal(peopleInInnerStorage, result);

17 }

and it has no trace of the Simmy library.

Summary

In this chapter, I argued that not all communication between objects should be represented as public protocols. Instead, some of it should be encapsulated inside the object. I also provided several examples to help you find such internal collaborators.