Setting up the Raspberry Pi Software

While the Raspberry Pi is a capable computer, we still need to install software on it to allow us to gather, store and present our data.

The software we will be using is based on the Linux Operating System. Because this is potentially unfamiliar territory (for those who haven’t used Linux or had some practical computing experience), we will take our time and explain things as we go.

Web Server, PHP and Database

Because we want to be able to present the data we will be collecting, we need to set up a web server that will return measurements to other computers that will be browsing within the network (remembering that this is not intended to be connected to the Internet, just inside your home network). This type of connection is called a RESTful service.

At the same time as setting up a web server on the Pi we will install PHP. PHP is a scripting language that is widely used in developing web pages. And because we will want to store our data somewhere we will add in the SQLite database. SQLite is a self-contained database engine that reads and writes directly to ordinary disk files. A complete SQL database is contained in a single file which can be transferred between platforms for backup or restoration purposes. SQLite is touted as the most widely used database engine in the world.

Install NGINX and PHP

The web server that we will use is called NGINX (pronounced “Engine X”). NGINX is an open-source web server that is often recommended for its performance and low resource consumption. This obviously makes it ideal for hardware such as the Raspberry Pi. In spite of being targeted as something of a ‘light’ application, it is extremely powerful, capable and it is widely used in large scale applications.

We can start the install process using the following;

We’re familiar with apt-get already, but this time we’re including more than one package in the installation process. Specifically we’re including nginx and php-fpm.

‘nginx’ is obviously the name of the NGINX web server and php-fpm is for PHP.

The Raspberry Pi will advise you of the range of additional packages that will be installed at the same time (to support those we’re installing (these additional packages are ‘dependencies’)). Agree to continue and the installation will proceed. This should take a few minutes or more (depending on the speed of your Internet connection).

Configuration

Firstly we should edit the default file that will get displayed as a web page if none is specified. What we want to do is to include the option to redirect to an index.php file.:

Replace the line:

with

Now we want to edit the portion of the file that will handle all requests for resources that end in .php.

Replace the section of the file that looks like this;

With this;

NGINX has its default web page location at /var/www/html on Raspbian. We are going to change the permissions / ownership of that folder by running following two commands:

This is necessary to let the ‘pi’ user edit the files in that location easily.

Now let’s create a suitable index.php test file with the following command:

We can restart the NGINX service so that the changes we have made can take effect:

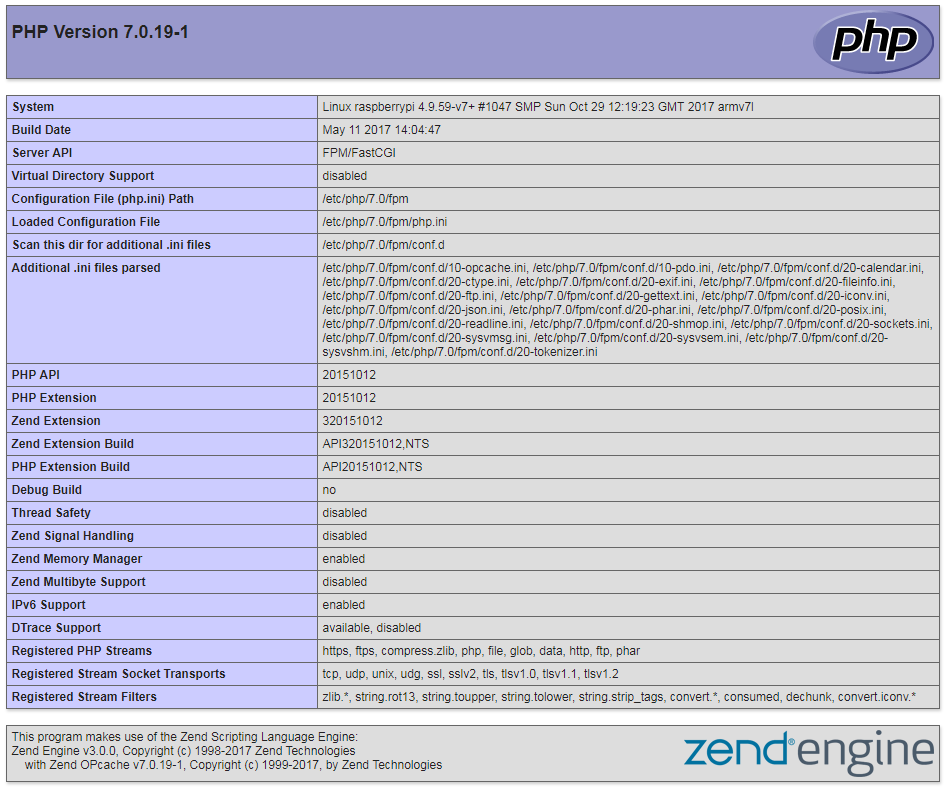

Now if we go to to the IP address of our Pi in a browser (in the example we are using it’s 10.1.1.120) and type it in to the URL bar to test. Something like the following should be displayed;

Marvellous.

Database

As mentioned earlier, we will use a SQLite database to store the information that we collect.

SQLite is incredibly easy to install.

And that’s it!

Because SQLite does not rely on a client-server relationship, applications that interact with the SQLite database read and write directly to the database file (or files). It therefore relies on the security of the permissions on the operating system to provide separation. This means that accessing the database from a separate computer is problematic, but it simplifies interaction for the user that is operating the database locally.

Create a database and a table

When we read data from our sensor, we will record it in a database. SQLite is a database program, but we still need to set up a database file that SQLite will read. In fact when we come to record and explore our data we will be dealing with a ‘table’ of data that will exist inside a database.

We will create a database called ‘measurements’ and in that database we will create a table called ‘light’ That table will record regular values from our light sensor (LDR) and the time that they were taken.

Creating our database and initiating interaction with it is done as follows;

Once the program is started we are presented with a prompt for the database;

From this prompt we can begin to provide commands and when we are finished we can exit from SQLite by typing in .quit. At any stage if we forget what command we should be running we can type in .help and the program will give us a list of commands.

We will create a table called ‘light’ which will contain a date time group field called ‘dtg’.

For the light value we will name the field ‘ldr’ and we will use the ‘INTEGER’ type.

Enter each of the following lines at the sqlite> prompt. The semicolon represents the end of the command.

We can then confirm that the table exists using the command ‘.table’;

There we have it! A simple database and a table ready to go.