Value Stream 2: Money & Economics

Value Stream 2 A3 Report:

- Monetary value may be measured through the “U2” framework of Usefulness and Uniqueness of any given PAOS

- Money represents the legal right and economic power to direct the flow of matter and energy in the form of goods and/or services

- Whether this right and power represents true-north value may be effected by creative financing, cognitive biases, bartering, substitutions, unpaid labor, legal regulations and criminal activity

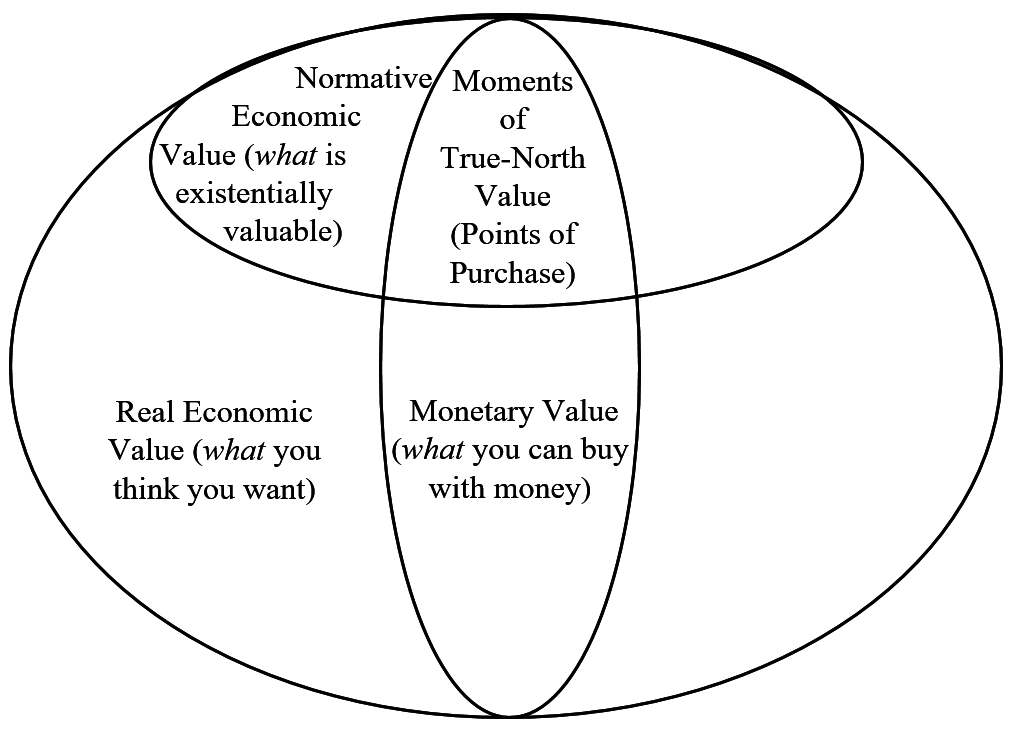

- True-north value in business is the intersection of normative value, real value, and monetary value at consumers’ point of purchasing a product and/or service that is uniquely useful to their lives and/or existences

- Energy is the fundamental element of money’s power, as evidenced by gold and silver being the direct and indirect color of sunlight, and some cryptocurrencies being limited by the amount of energy necessary to produce them. All fiat currencies likewise reflect these fundamental power constraints that include governments’ power to enforce them

- Consumers optimize their spending choices in neo-Darwinian fashion, constantly adjusting their budgets against their evolving survival needs

- True-north value measurement will never conform to Pareto-optimal models because of the above effects, and because optimization itself requires a degree of irrationality to stochastically discover what may be most beneficial in an open-ended universe

In Value Stream 2: Money & Economics, I remove the veil covering what makes money meaningful by introducing the categories of truth-value that lean metaphysically. This Value Stream 2 describes how money represents the true-north value that is derived directly from the conditional fact of consumers’ lives and existences, which most fundamentally defines who they are. Going one step further, this Value Stream 2 specifies that money, once received, gives you the contractual and economic power to redirect the flow of matter and energy back to yourself, customers, organizations and/or society through taxes and philanthropy. To manage cash flows well, you must keep in mind that while matter and energy move inversely to money, financial mechanisms like saving, investing and philanthropy can complicate that relationship.

In this Value Stream 2, I further relate the existential and physical value of money to what you commonly consider economics that in turn reflects itself in the money people pass along. Governments, businesses and investors quantitatively measure, model and report real value, but the secret meaning of money is found in truly normative value, which money on its face only partially reveals. This is because we generally monetize the real value that we need to live in order to seek the normative value that we live for. Thus, in the philosophy of Lean, normative economic value relates to customers’ metaphysical existences, and real value relates physically to customers’ real lives. The sales, marketing, operations, product development and strategy departments of organizations must understand these nuances of truly normative and real value to best support the prices they charge for product.

The prices charged to customers support who customers are at the point of purchase by intersecting why they buy and what they most truly value at the other end of the value equation. Since money measures the relative tradeoffs customers make among all available choices for best extending and optimizing their lives and existences, you must analyze these tradeoffs in the context of consumers’ overall real needs and all possible substitutes they have available to extend and optimize themselves. “Economics” as an academic discipline is simply a theoretical slot into which we place our ideas on how to estimate and quantify that true-north value best. Thus, separate and apart from money, real value is relative to a consumer’s wealth, his or her alternative means of consumption and individual preferences – real value is not directly correlated with the price of a product set in the marketplace that business people often confuse as being true-north value to an individual customer. This makes money two steps removed from Lean, true-north value.

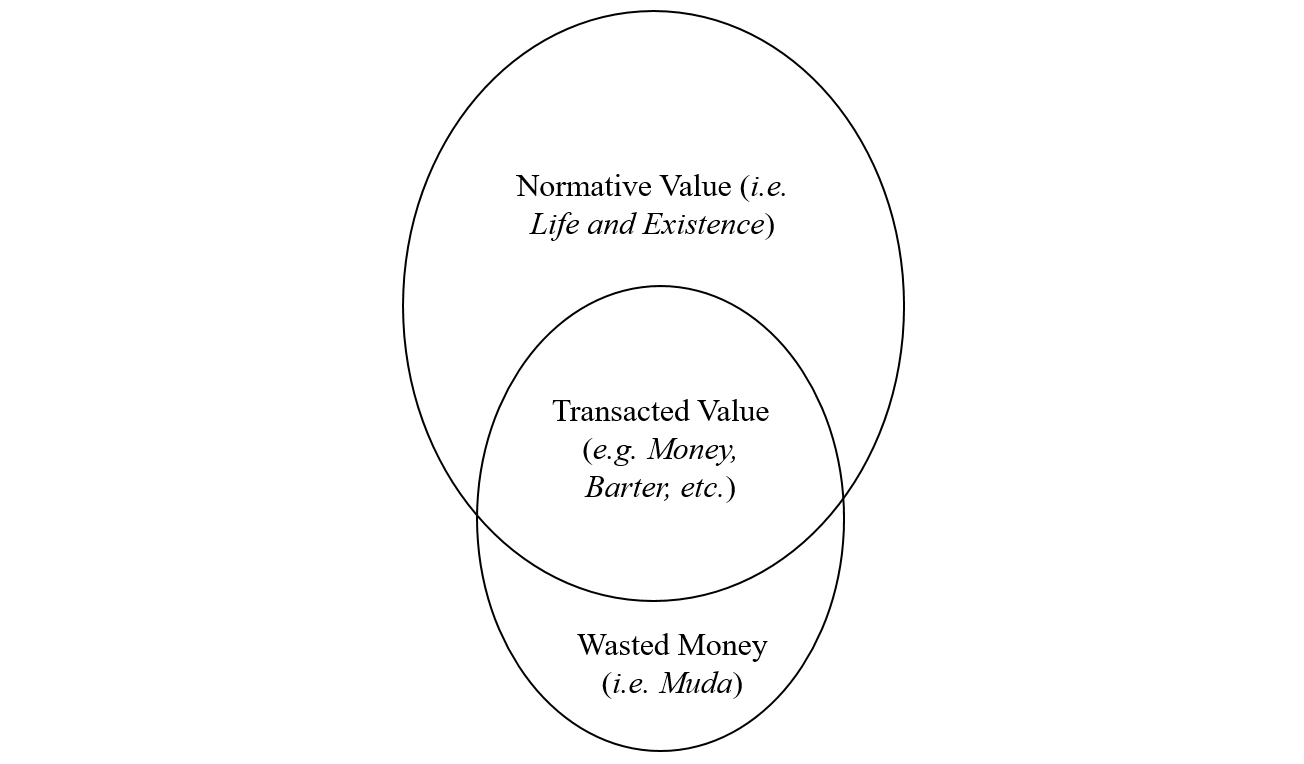

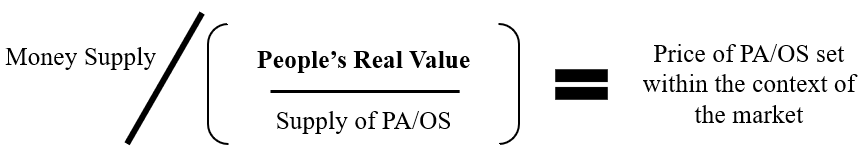

So while the philosophy of Lean generally defines “value” by how much money people willingly pay for some product, money is iconic but not wholly representative of the true-north value of life and business.1 As the well-respected Institute for Managerial Accounting recently confirmed, money is only the meta-language of economic activity and not the activity itself.2 But to create satisfactory models, economists tend to equate relative prices wholeheartedly with the relative normative value of all life and business, even though we know that is not always the case. In economic terms, these relatives prices of product at any given point in time are referred to as their monetary values. Start-ups and established companies usually describe the process of exchanging value for money as monetization, which can be seen here:

Through this monetization, the transacted value that customers most abstractly experience as the price of product is established in terms of money as follows:

In this Lean equation, you can determine the money supply, the supply of product, and the price of product in the market to approximate what people find meaningful by analyzing what they bought for the most money within their budgets. Note here that “People’s Real Value” is also a measure of product’ usefulness to people. You can reformulate this equation as the monetary supply over units of utility per product. Since this is a measure of supply (money and product) and demand (utility), this formula may be simplified into a “U2” formula, which is the measure of a product’s Uniqueness (supply) and Usefulness (demand), with the value in money being the final measure. To determine how much products are worth in money, one must simply measure its degree of Uniqueness and Usefuleness with this graph:

This makes perfect sense when you consider that there are many Unique things that are not useful, like “bad” art that no one cares to see. At the same time there are many very useful things that are not particularly unique, like the air we breath. The things we spend money on are both to some degree unique and useful to us. It is nonetheless a hard task predicting exactly what people most believe is unique and useful, and thus valuable, before they actually make a purchase. The IDEOs, CEOs and CMOs in all established businesses and start-ups try to do this each and every day when they decide what to produce and how to market their products.

Lasting, true-north value depends on normative value, which is both an economic and philosophical term meaning the true-north value that ought to be. Let’s define true-north value now in real value terms by saying that real value is the degree that consumers believe, rationally or not, that product will be uniquely useful. This means that a product will uniquely improve their lives and existences from their own personal perspectives in some way. On the other hand, truly normative value is that which actually makes a constructive difference in consumers’ lives and existences toward what ought to be within the universe, which businesses attempt to objectively measure via real and monetary value.3

When considering normative true-north value and money, this side of common sense says that while monetization is a para-scientific litmus test and one of the highest forms of value exchange, not everything worth something can be bought and sold with money. Much of economics is actually studying a subset of all normative and/or real value that gets exchanged in the market transactions that use money. It is common sense that not everything that is unique and useful can be exchanged for money, like the emotion of love. Likewise, other things are traded without using money at all. Barter represents the transacted true-north value of product without using money as a medium of exchange. For example, a significant portion of the global economy is in the form of unpaid, domestic labor from family members who freely work at home. Thus, money captures a large but incomplete portion of all transacted value as a lagging indicator of all that people find meaningful.

At the same time, as everyone well knows, not all money exchanged produces lasting, normatively true-north value. The real value for which businesses charge customers may possibly normatively affirm consumers’ lives and existences, but not necessarily. For example, eating may be normatively valuable for consumers to get energy. But eating junk food because it tastes delicious is not necessarily normatively valuable and useful in the long-run because other than the short-term matter and energy it provides, it harms consumers’ bodies and may cause illness. Consumers’ intervening factors like their physiological needs, their psychologies, ignorance or perverse economic incentives often create divergence between truly normative and real value.

Differences between normative and real value result because while normative value serves as the origin of all true-north value, consumers only experience normative value to the extent they really live and continually exist. While consumers only consider real value in the context of their real lives, their lives are only actually sustained by normative value as the only thing that truly matters. Real value just serves that need. Any real value that does not align with normative value will eventually fail on its own accord because it does not positively reaffirm consumers’ lives and existences.

However, consumers can sometimes be deluded by marketing tricksters to produce short-term profits.4 Consumers’ psychology within the context of their lives and who they are mediates - sometimes well and sometimes not - between monetary, real and normative value. Just like the divergence between normative and real value within consumers’ lives and existences, money as the narrative motif of true-north value may diverge symbolically from normative value. For example, do you know of a time when something was paid for when neither normative nor real value was fully received, such as when there was wasteful spending (i.e. Muda)? If you experienced that, then you or your organization transferred its money to the vendor, and along with it a right to direct the flow of a certain amount of matter and energy, but did not receive the normative or even real value bargained for in exchange. The money the vendor received likewise did not represent either the normative or real value it ought to have as determined by the deal you made with the vendor. Thus, ideally, real value is synonymous with normative value, which becomes moments of true-north value realized by organizations and customers at the point of purchase during a meaningful exchange of money - but that does not always happen the way it ought.5

To illustrate these moments of true-north value, here is a chart and equation showing the values as realized by consumers at their points of purchase within the possibly circular nature of their lives and existences:

Positive real value (economic supply/demand)

* Money Value (monetary, actual prices)

—————————————————————-

= Moments of True-North Value at the Point of Purchase

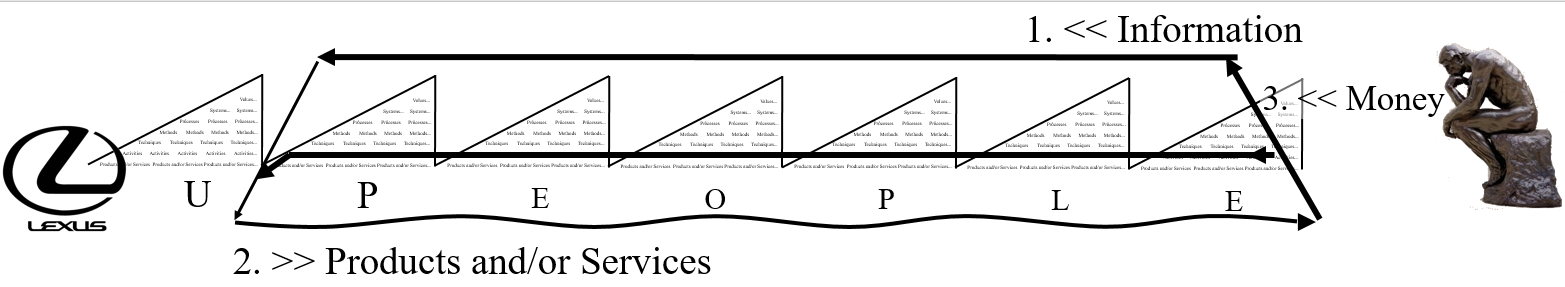

You can actually see these types of value realized in why consumers’ demand for what is uniquely useful flows down into organizations, and how customers pull out what organizations produce to satisfy those needs in return. Inversely, corporations pull their organizational information from consumers, and flow the product customers demand back up to them in Takt time. Organizations do this by comparing what customers demand to what organizations believe customers will value and purchase. They faithfully align their product with what they believe customers normatively and really want to buy now. In exchange, customers hope that the products they pull from an organization matches what they normatively and really value and find most uniquely useful to extend and optimize their lives and existences.

As described in Value Stream 1, you can see again below the pull and flow of these types of value reflected across the ID Katas for all the Value Streams of the U/People business model. In this picture, you can see who consumers are on the right and what they really value emerging from right to left in item (1). An organization ought to reflect what real value customers demand from left to right in how it produces and delivers product to customers in item (2). In item (3), customers return money in exchange for products across the point of purchase from right to left by faithfully believing that the products will give them real (and hopefully normatively) true-north value:

(1) < < An organization observes who consumers are from right to left<<

(2) >> It demonstrates why it understands what consumers truly, normatively value with the product that gets bought from left to right >>

(3) << Customers return money back to the business in exchange from right to left based on their perception of the value generated for them, which is itself largely driven by the products’ normative value <<

Ideally you want products reproduced in (2) to provide the fundamental, long-term, normative value demanded in (1). You want products’ real and hopefully normative value to support the meaningful money you receive in (3), which completes the infinite sigma σ around and through U/People as you can see above.

Since this intersection of normative, real and monetary value has the highest probability of being supported by society and law, an organization will be built to last if it focuses on this fundamental value exchange well before reporting season. When people speak of producing products that customers want, they largely mean providing products that builds people upward toward why people are in a normative sense, as may be adjusted by the circumstances of consumers’ real lives. That is the only legally and environmentally sustainable business value, as is fairly well recognized in this age by enlightened leaders, but is still extremely difficult for these leaders to justify and execute well in the face of short-term cost and competitive pressures from markets.

The Brazilian Real

Brazil’s economy during the 1980s and 1990s serves as a useful story to describe the relationship between normative and real value acting out within the secret life of money. During the last two decades of the 20th century, Brazil experienced hyper-inflation in all six of its currencies it issued during those decades. Prices in those currencies diverged significantly from the growth rates in real value based on the amount of products Brazilians received in exchange for their Brazilian currency. For example, Brazilians during that time might have been able to afford slightly more food for their families with what currency they earned, but that food cost many times as much in the prevailing Brazilian currency than they had on hand to pay for that food.

Inflation in Brazil became so extreme that in 1994 the Brazilian government began the “Real Plan.” Brazil began listing prices for basic commodities, like food, under the Real Plan in a fictitious currency called Units of Real Value, or URV, unlike the actual currency that was then in effect. Brazil invented Units of Real Value so that its citizens could see what monetary value they could use for basic commodities if Brazil had a stable currency like URVs. These fictional Units of Real Value became so powerful in the minds of Brazilians that they eventually named their currency the Real, which is still used today in Brazil. If you wanted to, you can exchange U.S. Dollars (U.S.D. $) for Brazilian Reals (R $). Below is a picture of a Real with the Effigy of the Republic wearing a Roman-style crown of bay leaves and a phrygian liberty cap. Notice that she is leaning toward people while looking back on economic history.

Precious Metals and the Locke-Lowndes Debates

Going back farther in time, The Great Recoinage of 1696 in England explains well why money functions mainly as a conduit for normative and positive real value within the channels of consumers’ value streams. The English government in the late 17th century decided to maintain a fixed rate of exchange between silver and gold. The great debates about this decision revolved around the writings of the famous philosopher John Locke, who is the same philosopher that conjectured many of the political theories supporting the American Revolution during the 18th century. To decide this issue, John Locke engaged in the “Locke-Lowndes Debates” with William Lowndes about England’s exchange rate between its pound sterling and gold bouillon.6

The reason for the great debate regarding the silver/gold exchange rate, was that England couldn’t keep people from physically shaving off their silver coins to less than a full “pound” of sterling and passing them forward as if they were. The silver Pound’s physical attributes literally diverged from the exchange value stamped on its face. Thus, the principle arguments of the Locke-Lowndes Debates revolved around two options for money: (1) whether money is best fixed to a specific physical element that people universally valued like silver or gold; or (2) whether money should be denominated in fictional units like the Brazilian Units of Real Value supported only by the government’s willingness to take it for payment and support its true-north value so people can exchange it for things they need to live and continue to exist.

Ultimately, John Locke successfully argued that the government should recoin its silver bullion to its official weight, making it truly represent what it purported to physically be. However, Locke’s arguments for the true-north value of money within the Lowndes-Locke Debates actually settled very little because centuries of similar debates have not resolved this issue. In case you didn’t know, the book, “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz,” originally written in 1900 and filmed in 1939 with its Technicolor yellow brick road is an allegory of this debate. Dorothy’s shoes were silver in the book, rather than ruby colored as they were in the movie, when she went to see the wizard of true-north value to get home to the golden wheat fields of Kansas that produce real food for people to consume.

The currency debates represented in “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz” culminated in meetings held in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, United States after World War II. The meetings resulted in channeling the value of the U.S. dollar through gold like the Lowndes-Locke debates. However in 1971, the U.S. government shifted the value of its currency to its own full faith and credit, thereby making the U.S. Dollar a truly “fiat” currency for people to believe in, so that the U.S. government could artificially regulate its monetary supply beyond what was possible with physical commodities like gold.7

Despite the U.S.’s and other nations’ currencies becoming “fiat” in modern times so governments can manipulate the money supply, gold and other precious metals still form the standard, physical “thing” that many governments hold in reserve to support the full faith and credit people have in those currencies. Investors likewise still hold precious metals to maintain the value of their investments during times of crises. After centuries of debate from Lock-Lowndes to The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, precious metals still stand as the most universal means of exchanging and storing true, economic value, and are what the U.S. Dollar would depend on if necessary. This begs the fundamental question:

They can sell precious metals for use in jewelry and dental fillings. Some electronics and chemical applications use them. However, in regards to the vast majority of the needs for consumers’ lives and existences that they normatively and really value, gold is an odd choice. Gold cannot be eaten other than in some liqueurs and chocolates as far as I know. Unless they were King Midas or Scrooge McDuck, consumers couldn’t possibly own enough gold to clothe or shelter themselves.

So, what is the normative and positive real value of precious metals that generally makes them the most popular basis for money? Consider the not very subtle coincidence that gold is the direct color, and silver the indirect color, of sunlight. Both symbolize consumers’ fundamental source of energy, which consumers subconsciously equate with beauty and ethics, which is technically referred to as, “Axiology.” Consumers’ lives and existences depend on capturing and converting matter and energy to live and exist with real and normative value, and precious metals simultaneously represent both. Energy is the uniquely useful thing any living system needs to exist, and precious metals represent it best.

With Money Comes Great Power

Thus, the very concept of making money is quite strange since it’s generally not used for anything but exchanging value and meaning. Who or what makes money a reliable source of meaningful, lean value for this exchange? Can you can make money simply by digging precious metals out of the ground? Can governments produce money merely because they enforce exchange value? Can a computer programmer make money meaningfully by trading a digital currency whose scarcity is in part dictated by the amount of computational energy required to make it, as is the case with BitCoin?

Since precious metals can only be mined to a limited extent, and only governments can make fiat money literally at will, modern business people clearly do not make money in any real sense, but rather, they make money truly valuable instead. An organization only makes money valuable by exchanging it for products that supports customers’ lives and existences. People only make money meaningfully valuable by transacting with it in this transcendental exchange. This is the classic question discussed by John Locke, John Maynard Keynes, and many other philosopher economists as to whether governments give currency true-north value in commerce.

Generally, these mainstream economists agree that, in the long run, money’s true-north value only gets made from the usefulness of the products exchanged for it – a usefulness measured by the extent it uplifts who and why consumers are toward what they most value and how they live and exist. However, in the short run, because prices coordinate when, where, how and how much people work, buy and trade, the quantity of money and the manipulation of financial instruments like interest rates really affect how consumers perceive the value of the products they consume. Denominations of money attempt to accurately symbolize this perceived value nonetheless.

Customers in an open economy ultimately make currency have meaning by trading, lending and/or investing it in exchange for products to live and exist. This in-turn allows customers to some extent use money to measure the real and normative value that products provides. On the flip-side, organizations make money valuable by solving problems that help people live and exist in normative and real value terms. Outside this customer-producer relationship, society measures an organization’s worth by how much currency customers exchanged for its products. The net volume of this exchange determines how much right an organization has to redistribute power throughout society, which is what society truly adores.

At the highest level of this discussion, not accounting for the many valid qualifiers in how things occur in the “real economy,” customers measure an organization’s normative and real value with the money they give to it. Thus, from a basic business perspective, people largely make money by affirming other people’s lives and existences to a greater and greater degree. The value of money gets “made” in the economy through this process to the extent that each person’s life is in fact improved in normative value terms. Real wealth gets made in the knowledge of the difference between what was, is, and ought to be. This affirmation thereby imbues money with ever increasing normative value because people’s lives and existences become increasingly sophisticated with its exchange.

Cash flowing through the economy makes money meaningful in upward fashion through customers’ specific wants and needs to live and exist. Even financial services create normative value through saving, lending, risk-shifting, and investing by altering the time and division by which people consume energy, thereby helping them become upwardly mobile within the cardinal order of the economic value stream. This economic value stream, which is the ever increasing volume of exchange of money for more products, makes money have true-north value as customers’ lives become improved by consuming more structured matter and energy to further exist in the real world. Thus, customers’ standard of living gets measured in-part by the flood of money exchanged overall.

Evidencing the physical origin of true-north value represented by money, even before John Locke first used “currency” to mean money, currency simply meant “run or flow” in old English.8 Locke applied the term currency to the units of cash or money to further emphasize the flow of Pound sterling silver and gold Bouillon though the economic value stream for the sole purpose of normalizing the standard ratios of exchange.[^122] In this way, money flowed from Locke’s perspective similar to how Toyota Motor Corporation perceives its Lean production processes flowing to Toyota’s customers in response to their pulling demand in Takt time, making Toyota’s customers rain money back down on the company in return. Thus, turning back to the original question, customers make money meaningful by exchanging it for products that makes the biggest positive difference to who they believe they are and wish to be. People refer to this market as the real economy.

Caveats to Measuring Money

Despite money’s surprising effectiveness in measuring the wealth of true-north value captured within all products, the process of making money meaningfully through a lean business ideology within an HQ requires you to consider some caveats to how money making actually works in the real world. I will now outline three major caveats to the ability of prices to semiotically reflect nominal and real value as:

- Supply and Substitutes;

- Barter and Self-service; and

- Other Market Distortions.

(1) Supply, Substitutes and the Warhol Paradox

Money’s ability to measure what consumers truly value in Lean terms depends on:

- The degree to which all customers believe all products exchanged for money in commerce will expand and optimize their lives and existences, or in other words, will be useful;

- The relative abundance of all products that can be bought with money to serve customers’ physical, emotional, and spiritual wants and needs, which more fundamentally energizes and optimizes customers’ lives and existences, which measures uniqueness; and

- The availability of substitutes (like barter or using one’s imagination for entertainment), for the satisfaction that all products bought with money delivers to all customers, which again is a measure of uniqueness.

To the extent customers believe that certain products with limited substitutes will extend and optimize their lives and existences, they must then set their budgets and spending priorities for that product accordingly amongst everything else they need and want to consume. Just like you, consumers estimate how product will affect their lives and existences and will adapt their consumption priorities accordingly.

Consumers adapt their spending priorities to best optimize and extend their lives and existences each time they consume. Thus, consumers behave like the finches on the Galapagos Islands, which optimize their beak sizes through successive generations to reach more food and water and thereby re-energize the lives and existences of their species. Like consumers, Finches on the Galapagos Islands right-size their beaks (i.e. consumers adapt their spending priorities) to consume the right amount of food and water (i.e. consumers adjust their spending budgets) to extend and optimize their species overall.9

However well adapted people might be, while some product may be really necessary for people’s lives and existences, like food and shelter, a critical product may be in such abundance that customers need to exchange very little money in order to obtain sufficient quantities of it, like water. The H20 molecule that is water may itself be unique, but water molecules as a whole exist in such quantity that they are (thankfully) not especially unique to most consumers. Water thus exemplifies well the relationship of transaction prices to normative value given that people need water to live, and nothing can substitute for water, but they must generally still pay for it, at least in the developed world. Consumers must generally exchange something to get drinkable water because unlike air, water usually gets monetized. We might though want to pay the Matsés people of the Amazonian rain forests to maintain its ecology so we all may continue breathing air well in the future. However, people generally assume that water will always be available at low cost, even though each person’s life and existence generally depends on other people to provide it consistently.

Should water become extremely scarce, assuming water was only available on an open market without governmental intervention, consumers would be forced out of necessity to exchange all of their money for it to the extent they needed more of it to live. Water at that point would be far more valuable and useful in normative and real value terms than any money in a person’s possession, as if an alchemist had turned water into gold. Water can thus be considered one of the most disproportionately inexpensive products that consumers purchase relative to its normative and real value to who and why they are.

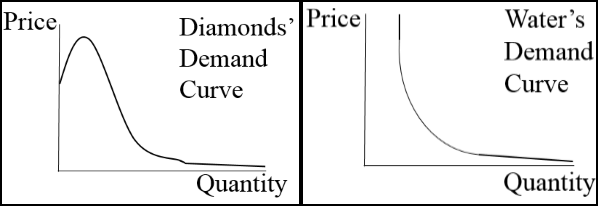

The famous economist Adam Smith, while chairman of the Moral Philosophy Department at Glasgow University, recognized this dynamic in what has come to be called his, “Paradox of Diamonds and Water.” Adam Smith first described the seemingly contradictory and divergent values between water that people need to live, and diamonds, that consumers do not need in any immediate sense to support their lives and existences. Adam Smith wrote that the prevailing price of water does not reflect the extent that consumers need it to live and would pay for it if really needed.10 Adam Smith used the terms “value in use” and “value in exchange” to differentiate between these differences in normative, real and monetary values.11

In economics terms, the relatively low market price of water tells you nothing about the price elasticity of water, or what consumers would pay for water should they really need it. Consumers’ biological needs in relation to their existences tell you that water would have one of the lowest price elasticities of demand, or in other words, customers would generally consume the same amount of water even when its price changed.12 Water’s price elasticity of demand tells you everything about its true-north value to consumers’ lives and existences in real and normative value terms and what consumers would be willing to pay you for it if necessary. Water is core to consumers’ being, and thus its demand is tremendously inelastic from a true-north value perspective.

In contrast to water, diamonds largely get demanded because they are both extremely reflective of sunlight and are abundant enough to be widely used for ceremonial purposes, such as for weddings and other gifts. And yet diamonds are kept scarce enough by the diamond industry to command high prices, even though artificially manufacture diamonds in laboratories do compete. I speculate that if only one diamond was ever found, its monetary value would be less than the prices for large diamonds today because nobody would be able to relate it to the one they, their loved ones or ancestors had on their fingers, or associate it with the religious ceremony of marriage. Thus, the diamond industry attempts to maintain an optimal level of scarcity for diamonds by providing neither too many nor too few of them, so the De Beers cartel maintains an optimally sloping supply curve in order to maximize the prevailing price of diamonds that you pay to them in exchange for love.

Substitutes, on the other hand, work in tandem with supply to mitigate the extent to which money accurately reflects the normative and positive real value of product to consumers in the context of their real lives.13 Consider this alternative. If water became scarce, its exchange value would exceed diamonds at some point, becoming higher than diamonds ever would as supplies of both diamonds and water reached zero. We can see some hypothetical demand curves for diamonds and water here as available quantities increase or decrease:

To illustrate the difference between use and exchange value in the philosophy of Lean, suppose that customers consume a liquid that provided every benefit of water as a perfect substitute.14 The prevailing market price of water and the price elasticity of demand against a changing price of water would be effected by the supply and resulting price of that other liquid in relation to water. Consumers’ demand curve for water would change because they now had a substitute to quench their thirst.

For one other comparison of this diamond-and-water paradox for a business ideology, I ask you to think about the differences in the relative monetary, real and normative true-north value between the Andy Warhol painting, Campbell’s Soup Can (Tomato), Lot 12, Sale 2355 (1962) that sold for $9,042,500 USD recently at a Christie’s auction house,15 and a picture taken by me of a Campbell’s soup can you might find at a local grocery store selling for $1 USD.

(2) Barter and Self-service

As a second caveat to the meaningful money making process that you should consider for a Lean business ideology, consumers only serve a certain proportion of their wants and needs in the process of purchasing the products you sell them. In other words, even in well-developed market economies, customers often serve their normative and positively real values by bartering for products with other people without using any money, just like how members of a family constantly renegotiate who does which household chores without paying one another for the favor. Consumers may serve their wants and needs through their own thoughts and labor, and directly exchange their own product with others through barter rather than with money. While neither barter nor consumers’ own thoughts or labor involve financial transactions, these activities that do not involve money effect the price of product consumers will pay you. Barter either substitutes for or displaces the product you sell due to the limited time people have to consume within their day-to-day lives and existences.

Books like, Leanism, exemplify this second caveat well by illustrating the limited ability of prices to measure the normative and positively real value, i.e. the full usefulness, of books. Consumers can often trade or lend physical books to other people instead of exchanging money for the same books from sellers. Also, consumers may write their own books, which would take a lot of the time they would have had to buy and read more books. Also, the satisfaction consumers receive from reading - the normative and positively real value received - largely comes from the intersection of their imaginations, knowledge, memories, and intentions with the books’ contents, which can only be truly determined after they buy and read a book.

Books’ prices do not effectively capture all of this true-north value to consumers since they may have a much richer set of experiences related to one book rather than another due to their life experiences, demographics, educations, interests and imaginations - essentially all that affects who and why consumers are. The price of a book may only reflect the normative and positively real value of that book in the aggregate if all the people who read such book then decided that reading experience was worth a specific price to pay among everything else they could have bought with the same amount of money. However, books’ prices, like for nearly all other product, do not adjust themselves in retrospect based on each customer’s individual circumstances and experiences from consuming them.

(3) Market Structural Distortions

The third caveat to measuring normatively and positively real value by prices paid considers factors such as monopolies, governmental interventions, structural market inefficiencies, and crimes. These factors often distort the connection between normative and positively real value, and the money exchanged for business’ product. For example, if you found that to do business someone asked you for a bribe, the “price” of the product you charged would then exceed that which would otherwise be set on balance by the market if you wanted to keep the same profit. On the other side of this analysis, if someone stole product from an organization, it would force the exchange of product for less than what would have otherwise been exchanged in a free market, which may drive up costs for all other customers. Likewise, addictive product like nicotine nearly eliminates customers’ ability to decide whether consuming that product best extends and optimizes their lives and existences once they identify themselves as being a smoker. All these factors keep the markets in which you operate from accurately reflecting consumers’ purely normative and real values.

Structural inefficiencies inherent in certain tax codes, political processes and financial institutions – each hopefully designed to combat other ills – inhibit the free operation of the economy in a way that would allow prices for product to more accurately reflect the normative and positive real value that customers consider product having in their lives and existences. For example, financial institutions and governmental intervention, while possibly useful, can also distort the ability of prices to measure what people truly value accurately. The collusion of government incentives and financial engineering, such as in the most recent global housing bubble, exemplify this point. Further, some industries like utilities tend to structure themselves into monopolies or oligopolies, either naturally from economies of scale, through collusion, or by governmental edict (think public utilities), thereby affecting prices through the monopoly’s or oligopoly’s purchasing power.

While not by any means exhaustive, all three of these major caveats exemplify the limited extent you can say that money’s nominal value exchanged for a product reflects its normative and positive real value to consumers’ lives and existences. You must understand these limitations to the process of making money truly meaningful to reach the greatest profit in the philosophy of Lean, unless you are a crook, which you are not.

Economics throughout history has addressed all of these subjects in some form or another, some of which you could find by procuring any economics textbook. I only mention these caveats to reemphasize how limited money prices are in identifying Lean normative and real value. You must understand what ultimately guides consumers’ consumption of product that indirectly leads to an organization’s functional profitability, making CFOs happy. I will now further explain the secret life of money as follows, due to money’s central importance in the philosophy of Lean, people’s notion of value and how money gets made meaningfully.

People’s Money Veil

Economists call these caveats about prices’ ability to measure true-north value a “Money Veil.” This money veil presents a significant problem with accurately pricing product and optimizing what people will buy. Prices will increase or decrease in the long run in response to changes in supply and substitutes serving consumers’ fundamental human needs, and changes in the supply of money, holding all else constant. Why? Because prices at their best merely reflect the amount of real value you provide that ought to contain the normative value that supports consumers’ lives and existences, and thus who and why consumers are. The money veil never ends because the only way you can measure the units of normative, true-north value you produce is by dividing the infinite universe by the finite number of people you serve, which leaves you endlessly speculating what units of product are truly worth. As our equation earlier in this Value Stream 2 describes, measuring the value of money simply sub-divides the universal demand to live and exist among all people currently buying and selling products to do so, which is the only value that truly matters for making money meaningfully.

Critically, the philosophy of Lean as described in much of this Value Stream 2 and the balance of this book brings this fundamental economic utility back into the business conversation like “The Lean Startup” did with empiricism. Leanism aligns true-north value with the rigorous test of normative and real value on their own terms. As demonstrated in the paragraph above, units of true-north value (i.e. universe / people) may not be measured in discrete units, but only through degrees of confidence as to what those units either may be or are not. Thus, however useful neoclassical economic models might be with their presumption of Pareto optimality neatly factoring what all people prefer, they do not explain how the Lean value that those models attempt to measure actually gets made, and thus how the greatest profit gets reached in an infinite universe, because rationality does not entirely contain what matters most.16

Off to See the Wizard

I will now further elaborate on the foundations of money’s use in commerce for you to get more meaning out of it regardless of how difficult it might be to measure money’s true worth. Most plainly, money has both tangible and intangible qualities. Tangibly, money assumes the form of coins, paper, or other commodities like precious metals. Intangibly, money forms accounting entries, and more recently, digital certificates like BitCoin. These digital currencies on their own exemplify money that is disconnected from a tangible commodity like gold. BitCoin takes money to the fictional extreme as a digital asset whose only use and support is its ability to facilitate exchanges of the contractual right to receive energizing product – exchanges that consumers somehow find meaningful to their lives and existences. Whether virtual currencies will succeed in the long-run given that they lack deeply rooted customs, governmental support, widespread acceptance as payment, and carry technological risk, remains to be seen.17

However, the only difference between a digital currency like BitCoin and a governmentally issued fiat currency like the U.S. Dollar at this point in time, is that a government enforces its own currency’s use as legal tender, accepts it as payment for taxes and government fees, has substantial reserves of tangible commodities like gold, and supports it with a military if necessary – most digital currencies have none of these qualities.18 These qualities of governmental fiat currency vastly differ from any privately created digital currency disconnected from any legal or military enforcement or commodity with normative and positive real value like gold, diamonds or water.19

Still, even digital currencies have some normative and positive real value, which they share with fiat currency. First, they create economic flexibility by allowing efficient online storage of true-north value that does not require any intermediaries like governments or private institutions. They provide the same psychological benefit of possessing money by providing a sense of security, opportunity or superiority. They improve on barter by keeping records, facilitating value comparisons, and allowing saving, credit, investment and speculation. But all money, in the form of digital currencies or otherwise, mainly serves as a conduit for normative and real value supporting who, why, what and how consumers are.

In contrast to digital currencies, people trade things that they can feed, shelter or clothe themselves with in exchange for precious metals so they may see the gold, silver and other beautiful colors they present. Precious metals serve people’s need for beauty, and for relating to other people by showing them off as status symbols. Also, the transferability, natural scarcity, and permanence of precious metals supports their longevity and ubiquity as a lean, global medium of normative and real value around the world.20

Funny Money

You can see further how funny money really is by looking at the seemingly counterintuitive relationship between currency, inflation, and productivity. Assume that a generic product costs one Unit of Real Value today, and new technology suddenly allows you to produce twice as much tomorrow with the same matter and energy. Keeping all else constant, the product’s price in URV would decrease in half. With this increase in productivity, holding all else constant, the price of the product has achieved disruptive deflation. People could then use their extra money to consume other product besides that generic product to better fulfill all of their wants and needs supporting who and why they are.

However, in the real world, while organizations constantly increase their productivity with new technology, you generally experience inflation in the product for which there are no substitutes, such as certain commodities like electricity. Despite our constantly reproducing more, you generally exchange more money for commodities like milk, rice, corn and water that does not change in character.21 Why should that be when we are producing most of these things more efficiently with less labor? The answer generally lies in understanding that over the course of history, governments increase the quantity of currency in their economies either by acquiring precious metals or by producing fiat currency in various proportions to the demand for and supply of product in their economies. Countries’ treasuries and central banks attempt to actively make enough money to control inflation in response to changing productivity, populations and demand, among other factors. But again, why?

Nations generally try to create some inflation to incentivize people to spend money sooner rather than later. By creating some inflation in tension with the deflationary forces of technological and business model disruption, people generally get more for the same amount of money today than they would tomorrow, which encourages consumers to spend rather than save. Deflation disincentivizes people from spending, which leads to what economists call the “deflationary spiral” leading to a vicious cycle of reduced spending. Thriving economies must encourage people to trade currency for the product they think will best satisfy who and why they are. The economy overall would decrease if everyone excessively waited to spend. The complete reasons for central banks’ attempts to maintain an inflation rate in the prices of product are beyond the scope of this book, but this illustrates governments’ manipulation of the ratio of currency and normative and real value being provided, and the divergence between prices and productivity.

Traditional, neoclassical economists and their books model in great detail the regulation of the supply of currency in equilibrium, and the tying and decoupling of currency to precious metals such as gold along with rising populations and living standards. In the end though, for purposes of this book and fundamentally understanding what lean meaning money has, you should understand what fiat currency is in relation to those things with material value, like precious metals. In the long run, setting aside any of the relatively minor practical uses of precious metals, the quantity of money really does not matter but for people’s using prices to coordinate the relative trade-offs they must make between their options to consume product to better live and exist within the context of who and why they think they are and want to become. Ultimately, customers don’t care about the cost of products, but rather only what opportunities they can realize or threats they can diminish with all the money they have at any given point in time to extend and optimize their lives and existences in relation to all other consumers in the marketplace. Prices only determine what solutions consumers must trade to best resolve their problems within their given situations, and if a price drops they simply shift that calculus along the slope of their demand curves.

However, as the famous economist John Maynard Keynes pointed out, even if money was just a medium of exchange, meaning very little by itself in the long run, prices affect many consumers’ short-term decisions.22 Further, the neoliberal Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek famously showed that people used the prices of product to coordinate what they bought across the economy, which is how prices change people’s behavior in the short run. Thus, central bankers adjust their short-run policies about money to align money’s value with what consumers really need to better live and exist.

Traditional and Modern Measurements of Money

Mainstream neoclassical economics, which has done as much as any field to try to measure and quantify the true-north value of money as utility23 or revealed preferences,24 has generally abdicated the task of understanding the foundation of money’s value to others. Neoclassical economists reasonably decided that they could not peer into consumers’ minds with any precision given the complexity of people’s thoughts, emotions and actions in the context of their real lives.25 Instead, mainstream, neoclassical economists chose to examine people’s purchase decisions retrospectively, to consider only what they reveal as being truly valuable with the money they spend. These economists do not try to measure what people will buy or pay based on underlying positive real value (or much less normative value) measurements other than what people have bought in the past.

Economist Paul Samuelson introduced Revealed Preference Theory in 1938, which mainstream economists have used ever since to quantify what people truly value through what they buy, rather than peering inside people’s needs, motives, morals and ethics.26 Samuelson mathematically modelled his Revealed Preference Theory as being logically circular or tautological toward customers’ end-goals, since he assumed that people only act to maximize their own utility as expressed by what they reveal they prefer.27 In other words, Samuelson believed that people buy simply to further be without any further objective supposed, which is important philosophically as you will see. Please keep this circular perspective on Revealed Preference Theory firmly in mind as we go through the balance of this book because it is a conundrum that the metaphysics of Lean attempts to delineate.

Not coincidentally, on the cover of Eric Ries’ book, “The Lean Startup,” you can see the Zen symbol of ensō of a near-circle created by a single brush stroke that symbolizes minimalism, strength, elegance, and the universe. This symbol also represents Ries’ “Build-Measure-Learn,” mythology, and the seemingly tautological empiricism of Samuelson’s Revealed Preference Theory:

Similar to the ensō duality as a near-circle, Revealed Preference Theory and most mathematical economic models fail to completely predict actual economic data since they do not account for consumers’ bounded rationality. For example, economists have shown limited ability to accurately predict countries’ Gross Domestic Product,28 even though a little additional accuracy can be highly profitable.29 The fact that marketing departments and advertising agencies do not widely use these econometric measurements like GDP at the micro-economic level to predict what consumers will want to buy evidences econometrics’ general lack of both accuracy and precision at the micro-economic scale, boiling up to a similar lack of accuracy and precision at the macro-economic level.30

Thus, in practice, neither marketers nor financiers primarily base their decisions on neoclassical economic models like Revealed Preference Theory, though they might use them within a stream of larger analysis. Governments’ central banks rely on neoclassical economics to a much greater degree. Central banks’ use of econometrics leads to the irony that what business people use to measure what people want is largely done under economic policies set by completely different value measurement methodologies.31 Due to these known deficiencies in neoclassical equilibrium models, we are witnessing today a thoughtful, and empirically based reintegration of new forms of true-north value analysis into them. Behavioral economics represents one of these new fields, but other fields such as anthropological, evolutionary and agent-based economics are increasingly employed as well.

The problem with Revealed Preference Theory is that people’s choices in determining how to best be who and why they are, such as choosing a lean diet because they consider themselves to be health nuts, are often contextually influenced by both physiological and psychological factors that exceed simple calculation, which reflects the imperfect relationship between real and normative value discussed earlier. For example, physiological factors may include ones such as varying nutritional needs, such as if you were otherwise deprived of nutrients provided by certain food that your body craved. Psychological factors could include suggestive advertising such as from the orange juice industry that made you associate the color orange with good health due to the vitamins in tropical fruits. The interplay between consumers’ psychological and their physiological processes influences what they decide to purchase and prefer to reveal.

Despite those psychological distortions to measuring normative value, the purchases consumers make still reveal their normative preferences to a large, though imperfect, degree. Normative value originates much further back from the point of purchase than is usually understood as “value” since normative value emerges from consumers’ fundamental living processes. Thus, people’s revealed preferences could be measured in front of the point of purchase if you knew every possible detail regarding consumers’ physiological and psychological processes in choosing, say, between apples and oranges, cashews and almonds. We loose the ability to directly measure normative value in customers’ sheer complexity. In contrast, consider how much simpler insects’ revealed preferences are to model than people’s since you can more easily map the value streams leading to who insects are, and what insects demand.

The problem with measuring and predicting utility through revealed preferences is not only a matter of accurately measuring the pathways of all of consumers’ physiological processes, but also the part of people’s physiological processes that generate psychological meaning and ultimately their preferences. Psychological meaning created by what cannot be proven or readily measured often causes consumers to act irrationally. Hopefully, consumers act predictably irrational32 so as to optimize their lives and existences, but we know they do not always succeed.

In recent decades the field of behavioral economics and increasing amounts of digital information have provided some insight into the pathways leading to human preferences beyond just what people bought with money. Behavioral economics attempts to explain how people value things through the intersection of the fields of psychology and economics to move past traditional, mainstream neoclassical economists’ default position that positive real value can only be measured in any meaningful way through market transactions and equilibrium models. Behavioral economists do not assume that people always make rational decisions when consuming in the confusing confluence of life.

Psychologist Daniel Kahneman and economist Amos Tversky produced some of the best known of this work when they elaborated on the rational biases people have when making decisions.33 Kahneman and Tversky won a Nobel Prize for demonstrating something called “Prospect Theory”34 that people would rather not risk losing more than they would chance gaining when they know the specific probabilities of realizing each of their choices. However, in real life, people very rarely know the specific probabilities of the outcomes of their possible choices, as they would when gambling or playing a lottery. Prospect Theory can only tell you what people would rationally decide to do based on what they prospectively believed or guessed the probability of something was holding all else equal. However, since people are very bad at guessing the true probabilities of events, most of the time consumers must still attempt to measure what best extends and optimizes their lives and existences with limited data and bad guesses. Prospect Theory and other behavioral economic theories can only aid with better decision making by prospectively revealing and helping compensate for these rational biases where information or our capacity to process it is not sufficient. Both you and consumers must estimate probabilities so complex they generally trail off into purely intuitive speculation. Behavioral economics recognizes this boundary on consumers’ ability to pierce through complexity and accurately assess true-north value.35

Irrational, Process-Oriented Value Estimation

You can more logically and scientifically measure the lean meaning of money and economics if you shift your conception of exchanging product for money at customers’ point of purchase. You must exchange what you previously thought of as products and/or services as being objects and/or activities. The existential value of objects and/or activities (i.e. products and/or services) to one another is in many ways abstracted and quantified by the prices people pay for them. Consider instead products’ advancement of the physical and meta-physical processes inherent in people’s lives and existences for which they allocate their budgets and change their spending priorities to improve regardless of how much absolute cash they have available to spend or borrow.

You can measure these allocation processes in well established ways, such as through marginal, game and identity value theories. To truly measure the meaning produced by products though, you must measure all of the constituent processes that aggregate into who, why, what, and how customers need and want to live and exist, which is admittedly very challenging. These processes lead to people’s normative and real values that ultimately make meaningful amounts of money get exchanged for product throughout the real economy.

However, these processes also have an irrational element within the unbounded domain of an open-ended universe.36 For example, consider the study of ants by researchers such as E.O. Wilson, Eleanor Rosch, and Deborah Gordon who have substantially uncovered why, what and how ants consume. These researchers have shown that ants execute a mixed strategy of purely rational and intentionally randomized discovery models at the individual and colony levels, leading to some evidence that the collective activity of ants generates enough information to make and execute mathematically rational decisions without having to be conscious like you and me. Ants do this by incorporating seemingly irrational, randomized search as one of their Modi Operandi (their “MOs”).37 E.O. Wilson was even rumored to have an ant encased in Lucite etched with the phrase, “Onward and Upward!” to emphasize this rational end-goal of living ants despite their sometimes seemingly random behaviors and lack of conscious intent.

Optimal Slack

So is this why people do not likewise conform well to purely rational, Pareto optimal models of spending money when aggregated as a society? I (among others) propose that, yes that is why, because consumers’ adaptive processes produce by necessity a certain degree of statistical anomaly at the genetic and cognitive levels to optimize adaptive discovery. You might call this “optimal slack.” Ultimately, a Lean organization ought not become brittle like a permanently pensive thinker, but rather athletically lean as the Greek soldier Philippides running to Athens during the Battle of Marathon. Like ants in a colony, organizations and consumers ought to flexibly think to optimize who they are through creative and somewhat randomized adaptation to win the battle for survival. As will be seen, the search for meaning in life as the ultimate knowledge in an open-ended existence helps organizations and consumers accomplish that task. Understanding this can help you make meaningful amounts of wealth as well.38

Presuming you measured every human process comprising who consumers are that a given product advanced, you would still need some random variables in your estimations and predictions of true-north value because people are constantly extending and optimizing their lives against what they believe provides meaning as a form of Bayesian rational irrationality and mathematical optimization.39 This is a notion that is constantly shifting for people as they self-define the true-north value of what they find personally meaningful. Contemporary genetic and other evolutionary “best fit” optimization algorithms include random variables as essential components, which you see mimicked in consumers who behave in similarly random ways in order to best extend and optimize their lives against a universe of meaningful opportunities.40

Cash and Credit Flow as Meta-Economic Value Streams

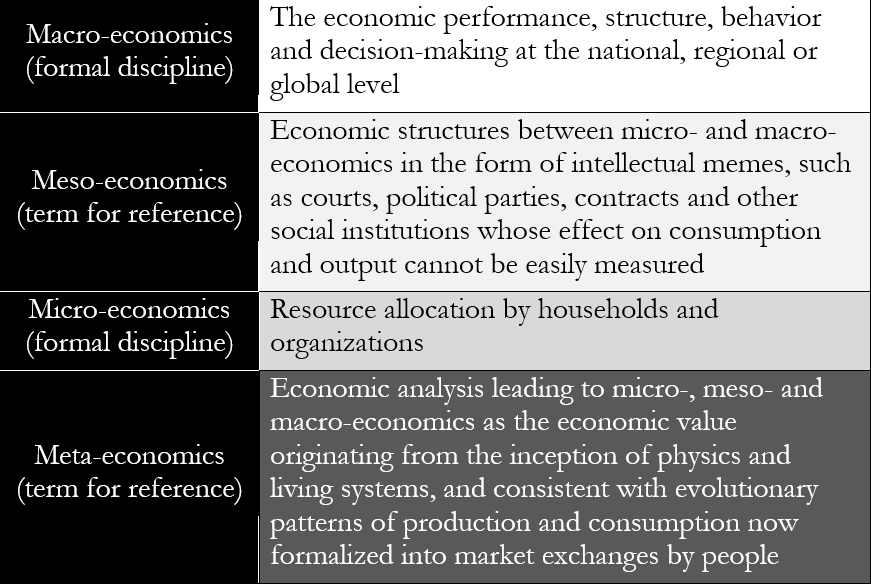

Because the search for meaning within the metaphysics of Lean inevitably takes you into unchartered waters beyond traditional philosophical and economic systems, you ought to peer into meta-economic and meso-economic matters, in the spaces around and between micro-economic and macro-economic ones. Doing so will allow you to see the entire, universal value stream that makes money meaningful overall by transferring matter and energy up and around the production and consumption cycle.

While, micro-economics studies true-north value at the individual, family, corporate and organizational level, and macro-economics studies economic performance and decision-making at the national, regional or global level,41 I define meta-economics as economic analysis that underpins micro- and macro-economic conclusions. Meta-economic value emerges from metaphysics and what consumers personally intuitively believe as to who they are and why they exist. Meta-economics then realizes itself in physics and living systems that ultimately create micro- and macro-economic data. Meta-economics is thus consistent with evolutionary patterns of micro-and macro-economics as demonstrated by market behaviors.42

Like meta-economics, meso-economics is also not a formal academic discipline but rather a term describing the lean economic structures residing between micro- and macro-economics.43 I further define meso-economics as the study of what affect intellectual memes, such as courts, political parties, contracts and other social institutions, have on organizations and people’s consumption and output in ways that are increasingly easy to measure as we improve the digital information about why and how people do what they do.

An organization’s people-focused, Lean ideology will mostly relate to the field of micro-economics at the firm level, but thinking in meta-economic and meso-economic terms should help you identify economic issues around traditional micro-economics to help you make money meaningfully. Here is a chart of these terms outlining these economic differences so you may lean through them:

Surprisingly, with the great time and minds dedicated these issues, many of the larger economic issues remain unsettled. For example, people still debate macro-economic issues like the appropriate levels of taxation and monetary policy.44 And they debate micro-economic issues like measuring how valuable something is to people by how much they pay for product. So a Lean ideology must still adapt to the changing micro and macro-economic social and political and academic environment in which an organization operates - all with degrees of uncertainty.45

The meta-economic chains extending through the business process of people serving other people in complex situations where the probabilities are not known in advance with precision, may be analyzed through the range of quantitative and qualitative analysis and micro and macro economic tools that we have discussed. However, this movement to the most fundamental aspects of Lean true-north value leads back to the natural sciences and the humanities to best measure and produce normative, real and money value.

Given all this uncertainty, I ask you at this point to further shift your conception of money as a means of exchange for product, to an even more abstract one whose store of true-north value is really more analogous to that of the real or perceived potential of product to improve who and why consumers are. Consider money to be the means by which you enhance consumers’ living processes by flowing to them the highly structured matter and energy (products and services, things and actions) that an organization produces. Since what consumers pay measures what consumers perceive to be the net benefit to their living processes among all available product, hope that consumers consider a product to be good and worth every cent to make money meaningfully within the metaphysics of Lean that a good business embodies.46

truth-value as Two Sides of the Same Physical Coin

Normative economics are thus equivalent to capturing, structuring and delivering matter and energy, which physically are two sides of the same coin of consumers’ physiological and psychological processes, to produce all normative value. In the prehistoric era, at the very inception of economic trading before the use of money, you generally would have traded an amount of product that took the same amount of matter and energy you used to produce it for other product that took an equivalent amount of matter and energy for that product to be reproduced. The product traded would have had the same marginal cost of effort spent to produce it.

This exchange value of matter and energy aligns with the labor theory of value heavily favored by Karl Marx. That fact does not make this discussion “Marxist” because once trade advanced in any small degree of sophistication, people produced advanced product that solved for strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats to who, why, what, and how people are, i.e. their real world problems regardless of the effort necessary to solve them. This trade related not just to the energy used to produce products but also to the relative energy efficiencies that product reproduced within those people who consumed them to more effectively support whole societies and nations. Comparative advantage depends on the extent trade extends and optimizes the lives of all people as a species, and not on the labor inputs into an economy, which is at most only an indirect indicator of the extent a nation’s product produces true utility.

The Marxist labor theory of true-north value should have been easily debunked as well on purely common sense grounds given Adam Smith’s “Diamonds and Water Paradox,” as well as the “Warhol Paradox” discussed earlier regarding Campbell soup cans on store shelves and museum canvases. You could sell a cup of water to a very thirsty person for far more than the energy you spent obtaining the water because of that customer’s need to live and exist. Instead of pure labor value, people subjectively decide and then verify whether a product helps their adaptation, regeneration and energization. Water uniquely does this if you or anyone else is thirsty, and owning a Warhol painting of a soup can may infinitely improve a person’s social status.

In modern society, people also contractually pool money, separating labor or energy values from the time the labor value was originally generated. Finance further removes labor from Marxist notions of value, because in addition to labor, time also allows people to better live and exist. Thus, prices reside in the tension between the energy (a.k.a. labor) cost of producing product on the supply side, and the optimization that product subjectively produces to customers’ lives and existences among all available substitutes on the demand side of the economic equation at a universal scale. That modern financial mechanisms imperfectly balance this tension is money and capitalism’s dirty little secret.

Nonetheless, the Marxist labor theory of value erred in two key ways, ultimately making it less desirable than capitalism as a commercial ideology. First, it ignored normative values that dictate what true-north value that products have as to who and why consumers are and personally consider themselves to be; and second, it failed to understand the real values that change the extent money represents normative economic value. Keep in mind though, economic conditions where competition is nearly perfect often drive the exchange value of commodities down to the cost of the matter and energy expended in producing them. Thus, the labor theory of truth-value has some validity as background information within a business ideology, but it should not predominate.

Thus, the only fundamental physical axiom in measuring real economic value is consumers’ tautologically self-regulating purchase history – either consumers are buying a product or they are not – which determines degrees of confidence you may have that a product will continue to be purchased by consumers. While economic formulas may model economic activity with increasing accuracy, you can only reduce economic analysis to mathematical formulas at either the meta, micro, meso or macro levels if they accurately model the fluidity of the systems grounded in natural laws of unknown origin that reproduce consumers’ lives and existences in an open-ended universe. Yet, history thus far quantifiably confirms that no consistent set of axiomatic expressions has been shown to represent and accurately predict all natural systems through economic data. So, we consistently progress onward and upward, eventually increasing our standard of existence, by further explaining what makes life even better in the best economic system we have to date without being totally confident as to whether we will continue to make money meaningfully.

Regardless of what system people may find themselves in along the twisting arrow of economic history, people will iteratively perfect themselves as living systems, however impossible that perfection may be. While the Japanese word, Kaizen, means good change, in Lean terms Kaizen further means a hypothetical, iterative pursuit of perfection.47 By capturing and converting more and more matter and energy overall and applying matter and energy toward universalizing who people are as living systems, an organization iteratively reduces disorder through the process of Kaizen in society.48 Customers’ marginal benefit in economic terms can generally be equated with the iterative, natural benefit an organization reproduces for them. Customers’ increasingly real and perceived need for product in order to try and perfect their adaptive, reproductive and energy gathering processes dictates how much of their budgets they are willing to give to achieve that end-goal. This energy expended to support the normative and real value of customers’ lives and existences makes the true, metaphysical value of money have meaning.

From this meta-economic perspective, money prices really equal a systemic benefit that customers perceive from consuming product that furthers some aspect of their living processes and ultimate existence. product provides structured matter and energy that systemically plugs-in like a hybrid into customers’ living processes, analogously to how software applications do within a computer’s operating system. All product functions like an App on an iPhone. All true-north value likewise systemically extends and/or optimizes some aspect of consumers’ living processes from their normative, real and really personal perspectives.

Inversely, consumers generally get money made by expending energy through their shopping as guided by their knowledge by deciding what works best for them. They decide how to receive matter and energy by allocating their money to various vendors in order to optimize their living processes. They allocate what best optimizes their living processes across who and why they consider themselves to be. Who consumers consider themselves to be includes who they associate with their identities. Consumers’ identities may include their families, friends, communities, nations or otherwise into the whole universe… or they may define themselves by the inverse of what is not or what people speculate may be but not everyone believes to be for sure. People generally engage in this identity crisis on a dynamic basis by balancing over time a very large variety of variables, including their religions. This makes specifically measuring and predicting true-north value, and people’s actions in general, so difficult. Thus, you must at least understand how structured matter and energy enhances consumers’ living processes for which they will pay meaningful amounts of money over the point of purchase for perhaps seemingly irrational reasons within the context of who and why consumers believe they are.

Moving Forward

With the meaning of money defined, now go beyond products, past the point of purchase, to the most fundamental levels of consumers’ lives and existences, to the place you want to go in their hearts and minds so you can most effectively exchange what they highly value in exchange for more meaningful amounts of money. After you move through the next few Value Streams of “Leanism: The Philosophy of Business,” you will find new channels through the U/People business model to apply your Lean business ideology to your organization.