Value Stream 1: Headwaters to Leanism

Value Stream 1 A3 Report:

- Lean is a global business discipline used to make money by improving commercial outcomes

- Lean has been applied throughout the business environment to all size companies and extended to all types of organizations

- Lean combines Western philosophies that investigate what is true through the scientific process, along with some aspects of Eastern religious philosophies like Buddhism to determine what has real value

- Many of the most truly successful business leaders today have seriously studied and written about philosophy

- Leanism leverages this tradition by summarizing and extending the philosophy of Lean to explain what “True-North Value” truly means in the context of all Lean business activity and life in general

- Leanism synthesizes and delivers this knowledge through creative symbolism and writing for improved learning

- Leanism provides a people-focused business model and a heuristic called an “ID Kata” that allows you to apply the philosophy of Lean to all business and life in general

- The ID Kata teaches you a method of forward analysis to discover true-north value by pursuing a series of who, why, what, and how questions

The business discipline of Lean is more than a set of manufacturing techniques or a way to start up new organizations. It is a holistic philosophy that can help you identify what to produce that people will truly value and purchase. Leanism shows you the way to wealth in all its many forms.1 To reach the greatest profit of all, you ought to lean philosophically to reach the highest point of true-north value for your customers using the metaphysics of Lean. You can make money using Lean by meaningfully observing and fervently divining who consumers are, why they may buy something, and what they want to buy from you, so you can delight them the most. Leanism extends your abstract thinking toward better understanding what creates true-north value to help you implement that knowledge in life and business. You lean philosophically so you can make meaningful amounts of money while feeling satisfied that you did good work.

However, like looking at the sun, such high-level, abstract thinking is painful, disorienting, and best done through a conceptual lens for you to see customers most clearly. Leanism filters all complex subjects to help you better see who consumers truly are from their deepest problems up through the universal value stream. You will then discover what they find most personally meaningful in the products and/or services you serve. I suggest that you put on a thinking cap and eye-shades before reading further because these abstract concepts will help you see true-north value if you learn to look carefully enough.

Since commercial value gets measured in money, money is the mythical icon toward which all true-north value in business leans. When deciding whether to buy now and receive meaningful true-north value from you, consumers consider how much money they must pay at the point of purchasing products and/or services. Likewise, you as a business person want to know how much money you can earn through great work. Without clearly understanding why and what consumers want to buy, and how you deliver their greatest satisfaction, you cannot uplift your profits to where you think they ought to be.

While what exactly consumers individually believe to be truly valuable remains beyond what all people commonly agree, philosophy logically coheres and mediates the true-north value of money within our overlapping consensus of the way life is.2 Importantly, philosophy will also guide you past any idolatry of money that will blind you to consumers’ true religion. When you lean metaphysically, you will consider how best to create true-north value for all people, which in-turn supports who consumers are and what consumers individually believe to be most worth their money.

Why Lean?

While the concepts behind Lean that lead to producing superior products have a long intellectual tradition primarily formed from the Western “Philosophy of Science” and Eastern religious philosophies, Lean consolidated those ideas and has become the leading business discipline/fad/trend/paradigm used by people to make money in our time. Lean as a formal business discipline was formed from studying what made the Toyota Motor Corporation so successful for so long. In the 1980s, business researchers developed the modern concept of Lean from this intellectual legacy and extensive body of practical knowledge. A gentleman named John Krafcik, under the tutelage of James Womack, first coined the term “Lean” in a 1988 article he wrote for the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) about Toyota’s highly successful production systems when he said, “[I]t needs less of everything to create a given amount of value, so let’s call it ‘lean.’”3 From that point forward, the term “Lean” represented a modern business philosophy whose tenets organizations continue to pursue and iteratively perfect today, which is well captured by this quote from Antoine de Saint Exupéry in 1939:

From a fundamental metaphysical perspective, Lean business techniques focus on creating the truest value by removing all forms of waste and adding only what most satisfies consumers’ demands, just as Toyota continues to do today. However, while not complex on its face, Lean demands a different way of doing business.5 In fact, since one of Lean’s main points is to wash away everything but that which provides consumers with value however truly defined, it is a far more abstract money making methodology than most businesses are used to considering. At the same time, businesses have evolved Lean into a practical philosophy of continuous improvement, which the Japanese word, Kaizen (改善), represents. Kaizen is a portmanteau meaning to restore (Kai (佳)) and make good (Zen (禅)) through thoughtful reflection, and is key to any continuous effort to reduce waste in an HQ.

In the spirit of Kaizen, Lean was iteratively improved in the 1990s and 2000s by intersecting it with more quantitative disciplines like Six Sigma that Motorola (once a division of Google but now a part of Lenovo) developed at the same time. Motorola designed Six Sigma in the 1980s to ensure production of its information technology within six standard deviations of statistical precision. Thus, businesses use Lean to accurately target what people most value, while Six Sigma and other quantitative methods precisely lean organizations of people in that direction. Countless books evidence this intellectual legacy of Lean, Six Sigma and other people-oriented, evidence-focused business insights that are referenced throughout the ten “Value Streams” of Leanism that you can surface with any search.

Thus, Lean is the best paradigm for philosophically analyzing business because it has the highest rate of problem solving power as evidenced by its efficacy in generating consistent profits.6 Lean has evolved to become widely used by most companies7 of all sizes in some way as part of their organizational DNA — from start-ups to large corporations — just ask any business person whether his or her organization uses Lean in some way!

Lean, like most business theories, must be approached abstractly but applied concretely through specific actions to determine what delights the most customers for the greatest profit. However, if any criticism has been levelled at Lean, it’s the irony that Lean practitioners overly rely on the plethora of tools, diagrams and instruments that Lean consultants produce without espousing an overriding ethos for their detailed implementation in the chaos of everyday business. Consultants promote these tools because customers prefer to pay for repeatable mechanisms than abstract theories that require deep thought to implement.

However, if you move beyond all of the tools, diagrams and instruments provided by Lean, if you study it carefully enough, you will see that Lean represents a history of thought from the Ancient Greeks, the European Scientific Renaissance and the Far East that extends into all we as producers and consumers think about today. In this amalgamation, Lean articulates a good overriding ideology - a good unified philosophy - because Lean accepts the possibility of, desirability for and progress toward an infinitely optimistic future to reach commercial Nirvana.8

Why Leanism?

The intersection of Lean tools along with the sound business philosophy of Lean can generate radical wealth in this domain.9 Yet, despite countless business books falling into the Lean canon, a gap still exists in the Lean literature due to these proponents failing to identify what true-north value businesses actually lean toward. “Leanism: The Philosophy of Business,” attempts to fill this void by embodying the intellectual legacy of Lean in a set of high-level steps you can take to make money meaningfully in-line with all consumers’ value streams.

While philosophy is said to “bake no bread,” the metaphysics of Lean helps you analyze what bread you ought to bake and how to bake bread that gets bought and broken. For example, baking either a wedding cake, Communion bread, or table bread requires you to satisfy consumers’ very different fundamental needs in Lean fashion. Knowing who consumers are and why and what they most truly value further determines how you will bake bread that helps customers better become who they want to be, whether that is either married, saved or well-nourished. If philosophy is dead, why not put it to practical use within Lean to find the true-north value of life and business and make money meaningfully? Lean metaphysically if for nothing else than to more effectively guide you to consumers’ point of physical, emotional and intuitive satisfaction.10

Leaning metaphysically toward consumers is not about endless speculation, but rather about analyzing data with continuously new metaphysical perspectives in a unified way to make real decisions about how to make money well in all business environments. This isn’t science fiction, but rather the best knowledge available about reality itself. It solves the problem of explaining what true-north value is and how to create it for money. It does that by explaining who and why consumers are in the grandest scheme of things for you to apply specifically to business. Knowing how to analyze business data implies that an organization knows what realistic, true-north value that data reflects and why the data means anything at all to consumers and other stakeholders, which philosophy explains. Thus, organizations lean metaphysically to extend and optimize their businesses through their data about consumers’ lives and existences and what they personally find meaningful.

However, analyzing valuable data without continuously knowing who consumers are and what they find most meaningful prevents an organization from reporting as much money as possible inside its headquarters.11 Getting to this point of profit in the metaphysics of Lean requires both deeply respecting humanity and always improving, such as how Pfizer’s upper management periodically does within so within its global HQ.12

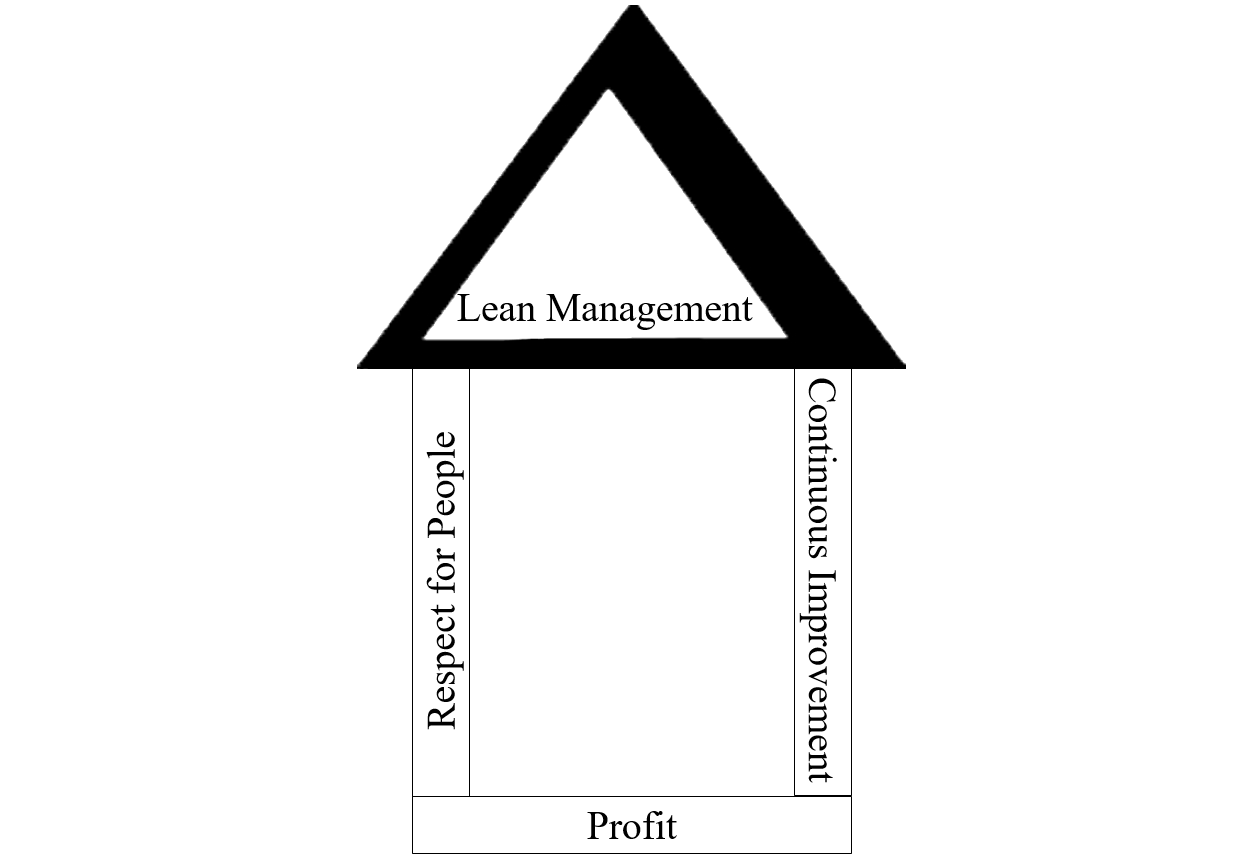

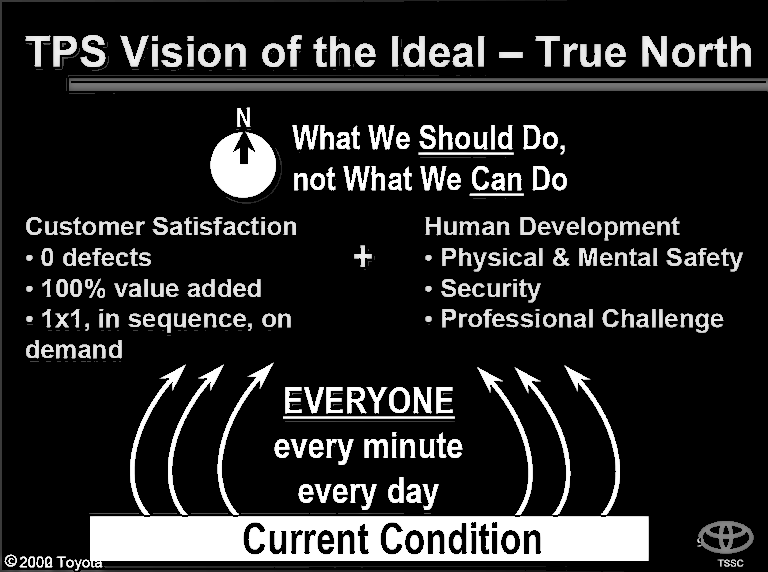

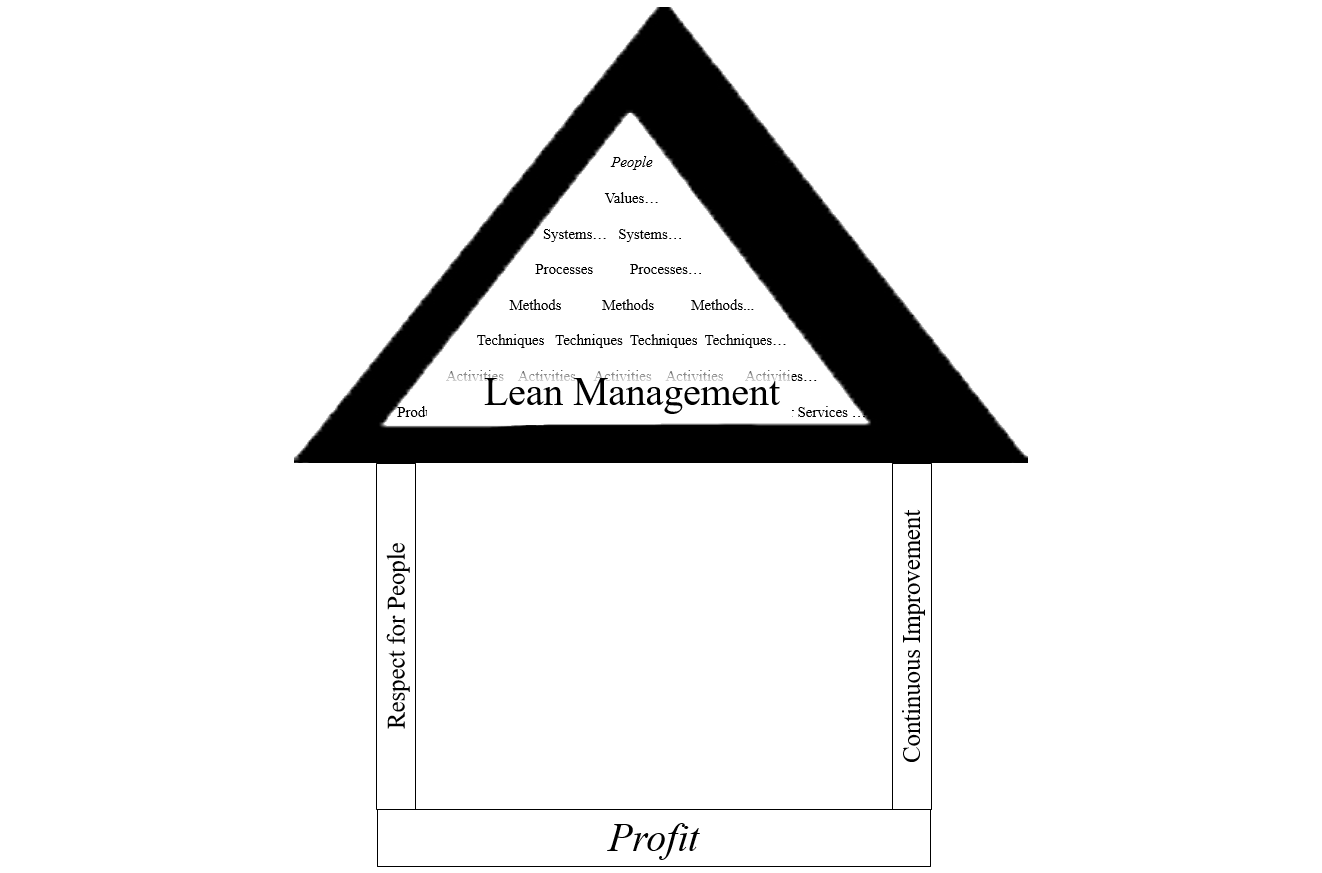

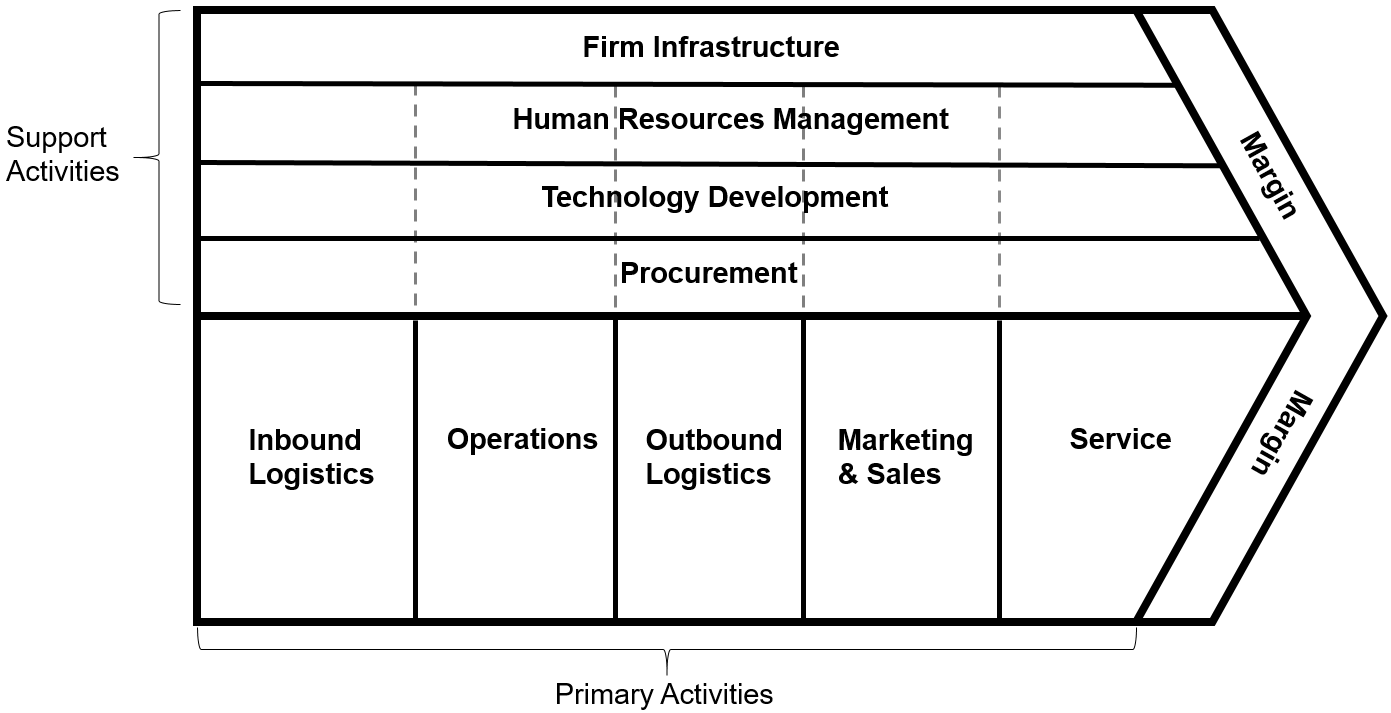

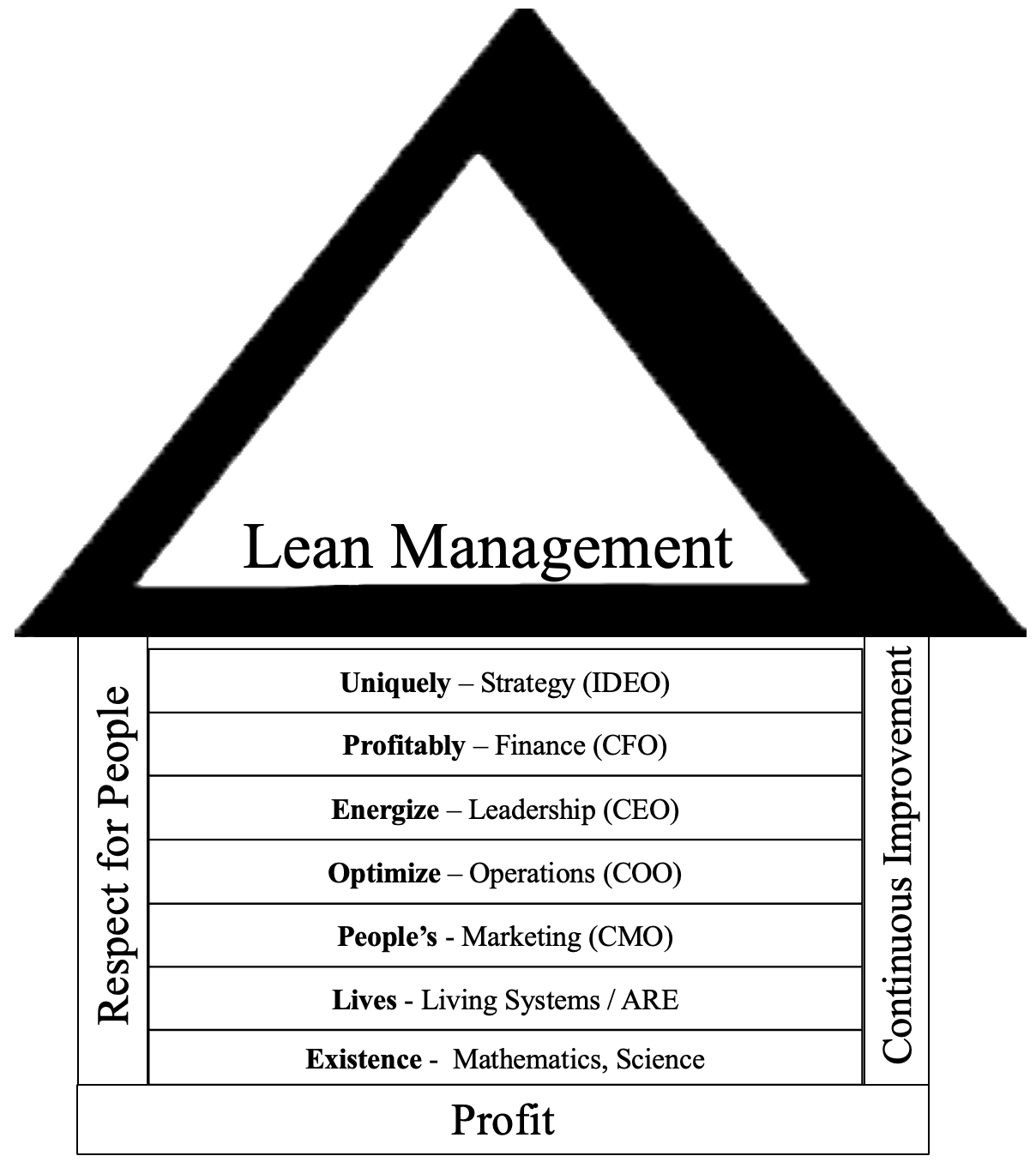

Thus, the two pillars of any Lean HQ are Sonchō (尊重), which is Japanese for “Respect for People,” and Kaizen (改善), which means good change and has evolved to further mean “Continuous Improvement” in Lean parlance. To help you visualize these concepts, here is a diagram of a corporation’s HQ with a Lean management system up top using profit as its foundation and bottom line:13

Getting Around “Leanism”

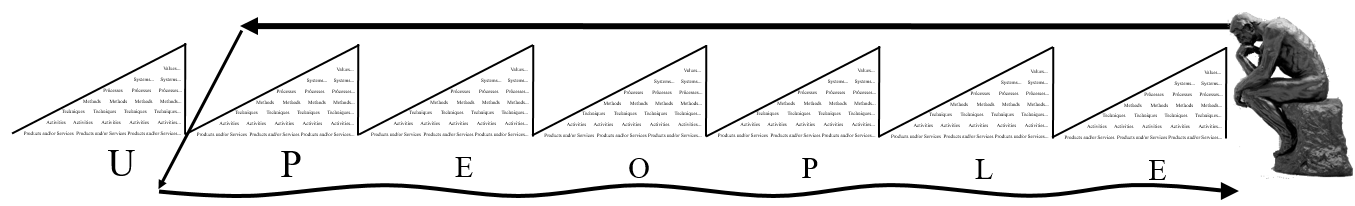

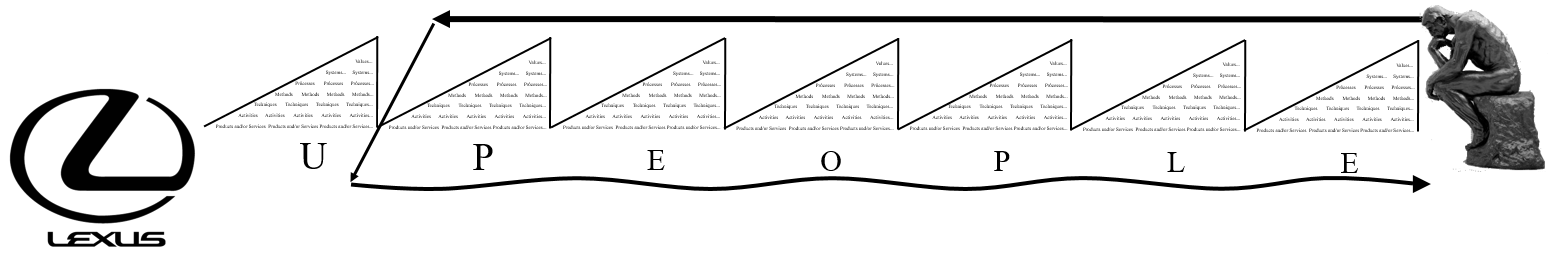

Leanism structures its chapters, which I call “Value Streams,” around the “U/People” (again, “You lean toward people”) acronym. U/People stands as a meta-heuristic, upper ontology and business model14 for use by an organization to Uniquely/Profitably Extend and Optimize People’s Lives and Existences.15 “Lean” (aka “/”) within this “You lean toward people” acronym stands as an adjective indicating those people and organizations that lean metaphysically toward other people. Lean also acts as a verb implementing the philosophical imperative to make money the right way toward what consumers most truly value. For example, Toyota Motor Corporation leans metaphysically as a fictitious person,16 through its employees and other stakeholders as natural people, and toward its customers’ true-north value in an open-ended universe, which I will explain further as we go along.

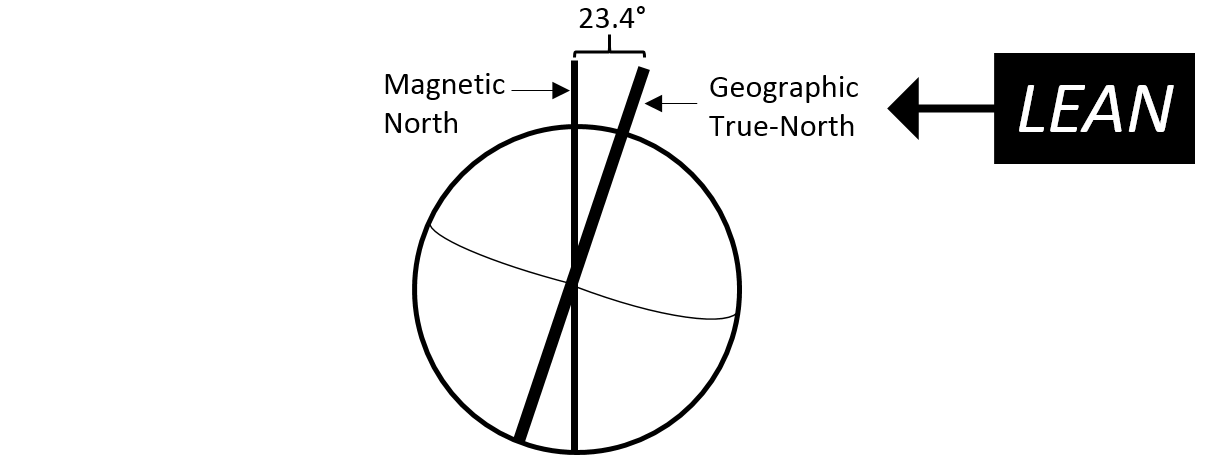

Leanism runs quickly through each part of its main acronym, from one Value Stream to the next, by synthesizing the essential qualities of each for you to better relate subjects and build a personal “AHA” moment and organizational House of Quality (an HQ (舎)) and ideology from its two pillars - Respect for People17 and Continuous Improvement. This business model and vocabulary - as supplemented by all the work cited within this book - allows an organization to point its own “True-North” value compass leading out from its “House of Quality” toward profitably analyzing data to increase consumers’ standard of existence. “True-North” is the metaphorical direction of all true-value in Lean terminology, and an HQ / House of Quality / Head Quarters is where true-north value is reproduced and a profit is reached.18 As you can see here, “Lean” symbolism gets conveyed in the geographical direction of “True-North,” around which the earth circles while moving forward in time.

And “True-North” is where you chart your way to the greatest profit, slightly off-center, up and to the right.

As you might anticipate, this monograph on the philosophy of Lean could never be exhaustive within a single volume, much less a part, Value Stream, section, paragraph, sentence and/or word as may be devoted to any given aspect of this universal subject of true-north value that defines all problems, which ultimately makes all money meaningful as well. The further analysis and research I could do for this book is necessarily limitless, since like every thing, it could be infinitely improved. My end-goal is to provide you with a fountain of knowledge that always allows you to identify and improve who consumers are by intuiting, inferring and possibly inducing why they buy, and then assumptively deducing what should be reproduced and how you ought to create truly valuable products and/or services for them.

To help with this stretch assignment in plain-language philosophy so you may better understand the genesis of true-north value, this discussion cites the brilliant19 work of those who understand the contents of this book so well. The biblical amount of footnotes and further commentary ought to supplement your own personal discovery and learning while building a Lean HQ and ideology for making money meaningfully. I footnote where I can recognize prior thoughts, but given the breadth of this discussion bridging together diverse disciplines, please forgive inadvertent omissions that I am sure you will surface! I strongly encourage you to use the references and footnotes as best fits your reason to lean philosophically that you have in an HQ. The footnoted references support all that I write by providing you from the ground up with even better explanations that will give your own research further reach.

The business concept of Lean, as philosophically expanded by this book, is a vector of discovery by which you may synthesize existing, well-regarded Eastern and Western philosophies, ideologies, -isms, and business concepts in an HQ toward the ultimate goal of delighting customers for a profit. If you must call this something, you might call it a “Universal Optimism,” which anticipates the panglossian future value consumers and organizations will receive by your doing the right thing.20

Further Reasons to Leanism

If you need some further reason to lean metaphysically toward making money meaningfully, the following six reasons elaborate on why you ought to do so:

1) Consistently Reach Higher Profits. You can help an organization meaningfully differentiate the products and/or services it creates to reach a profit the right way. Ideally, a profit represents the true-north value in customers’ lives and existences created with products and/or services over and above the economic cost deducted in order to produce and provide for them. In a competitive environment, a profit also represents the true-north value provided to consumers in excess of the similar value consumers could have received from competitors.21 However, as you know, you must qualify this idea of true-north value’s association with financial profit since it comes with many caveats, like the “Tragedy of the Commons” where people free-ride on public goods like natural resources.22 Nonetheless, ideally, you profitably uplift customers, employees, investors and society best while avoiding such pitfalls by leaning up toward true-north value. In the end, you must lean metaphysically so you can consistently understand what will be truly profitable for all.

2) Develop a Core Ideology, Purpose and Values: You ought to adapt the U/People acronym and business model to an organization’s core value theory to make money meaningfully by leaning through all business fads/trends/disciplines/paradigms, including Lean itself that will eventually fade away given sufficient time.23 Ray Dalio, founder of the world’s largest hedge fund, Bridgewater Associates, writes, “… adopting pre-packaged principles without much thought exposes you to the risk of inconsistency with your true values.”24 Ultimately, an organization must relate customers’ true-north values to what they pay so a business can more effectively serve them products and/or services that expand and optimize the profits that rain down on managers and other stakeholders.

3) Evidence Long-term Efficacy. Beyond zealously producing short-term profits, applying humanities-focused business models like “U/People” and concepts such as “Corporate Social Responsibility,” improves business performance and increases stakeholder returns in the long run.25 Common justifications for humanities-focused value streams flowing within such business models and concepts include reputation management, risk management, employee satisfaction, innovation and learning, access to capital, and financial performance.26 Collins and Porras in “Built to Last” said that they did not find a profit motive to be the dominant explicit motivation of successful companies, but rather found that profits were generated by successful companies as a consequence of their seeking to provide the greatest value to consumers.27 The authors found that organizations pursuing consumers’ greater purposes are better able to motivate employees and other stakeholders while uniquely expanding and optimizing their profits over the long-run as an indirect effect.28 This concept has been reinforced by numerous other studies as you see referenced throughout this book.

In regards to how a business treats internal stakeholders, scholars Jeffery Pfeffer and John Veiga wrote a well-received article in 1999 titled, “Putting People First for Organizational Success.” Pfeffer and Veiga compiled a number of studies correlating the efficacy of well-run people-services programs and organizational profitability.29 A number of subsequent studies confirmed this as well.30 These authors’ research suggests that corporate cultures that self-organize themselves around what people most value perform better overall in the short, medium and long-run.

4) Innovation. Chiat\Day art director Craig Tanimoto asked each of us to “Think Different” in Apple’s same titled 1987 ad campaign.31 By pursuing the philosophy of Lean in the practice of true-north value discovery, you too will think differently about how you may build wealth by upgrading consumers’ lives and existences. Where the metaphysics of Lean really takes off is in pursuing orthogonal innovation because this solution space is where you can become unmoored from organizational constraints.32 As André Gide wrote in, “Les Faux-Monnayeurs,” in 1925, “You can’t discover new lands without losing sight of the shore.” When you lean metaphysically, your business analysis reaches further heights to allow you to experience greater consumer insights. Philosophical, abstract thinking allows you to draw lines between science and the fundamental human needs being addressed, providing a way for you to exchange competitors’ solutions for truly novel ones that are at least ten times better. Philosophy thereby allows you to evaluate Lean and all business theories organically from first principles to reach new outcomes to make money meaningfully at a workplace.

An organization ought to lean toward who consumers are to identify how to improve their basic human condition for a profit. Clearly understanding what consumers believe is phenomenally valuable and allows an organization to pivot flexibly toward what better solves consumers’ problems for the widest margins. As Steve Jobs said to the BBC in 1990, “No market research could have led to the development of the Macintosh or the personal computer in the first place,” However, I believe that Jobs used a combination of his intuitive empathy combined with the Japanese religious philosophy of Zen Buddhism, as evidenced by the correlations between his quotes and the philosophy of Lean espoused within this book.

Innovating requires an organization to find the confluence of what is possible, practical and demanded. Data analyzed through metaphysics toward what consumers most meaningfully value can help you find this intersection. By leaning philosophically, you may iteratively reconfirm that your Lean thinking remains on this side of non-sense (or non-cents) as you develop and market products and/or services. You can then incrementally test whether customers really experience a revelation of true-north value from the products and/or services you reproduce. Through this process, an organization coheres its business ideology with what consumers will actually purchase so they increasingly congregate at its stores.

5) Increase the Probability of Profitability. The principles described in this book increase the probability that you will make profitable business decisions despite fickle markets. While empirically studying whether you make more money when you lean toward what consumers most meaningfully value is outside the scope of this book, these principles cohere with well-regarded advice from scores of renowned tycoons, scholars, philosophers, theologians and poets who are all liberally quoted here.33 Leanism improves the chances of effectively achieving its obvious yet often disregarded main point that an organization ought to fervently seek true-north value to make money meaningfully. This book provides the fundamental structure for you to answer for yourself why and how that occurs.

You may quickly measure how effectively you lean metaphysically by analyzing how consumers respond when you follow this book’s precepts with what they purchase. While predicting human behavior always involves some degree of randomness due to consumers’ rational irrationality, which limits the accuracy of any business projections you make, Leanism allows you to better identify the difference between what is tactically correct and what is not for the greatest chance of achieving profitable success. Or, as John McKay the founder of Whole Foods Market that was sold to Amazon says, “Values Matter.”34

6) Meaningfully Analyze Data. Most importantly, observing true-north value in life and business allows you to guide your business methods, particularly when clean data is lacking, as increasingly large datasets improve the ability to quantify and understand what consumers most truly value beyond what they purchased. Leanism connects metaphysical abstraction to how consumers actually live, exist and confess their deepest needs within whatever blessed consumption data you may obtain.35 Lean is the philosophy of business, and business remains the most legible of all the social sciences.

The best, most recent attempts to quantify true-north value outside of economics and marketing have been in the fields of psychology and neurology. Behavioral economics and “marketing neuroscience” increasingly identify what consumers most truly value before they pay a price by quantifying consumers’ systemic biases and responses. However, to complement these studies and balance a dogmatic focus on obtaining data, Leanism leverages conjecture through theory to discover what matters most both before it can be counted and when it cannot be counted at all. While the management consultant W. Edwards Deming famously said, “In God we trust; all others must bring data,” Leanism helps you get the right data and make sense of the data you receive by asking the right questions in the first place.

This mentality of approaching business through profound interrogatories is similar to what the famous management guru Peter Drucker wrote about the Japanese, the same Asian culture that produced Toyota’s Production System, when he stated that the most important element in decision making to them is defining the questions to be asked.36 Likewise, Jeffrey Leek, Ph.D., professor of data science at Johns Hopkins said, when further quoting Dan Meyer, that asking the best questions goes to the heart of the philosophy of data science itself.37 Or, as Albert Einstein and Leopold Infeld wrote in their 1938 book, “The Evolution of Physics,” that the formulation of a problem is more essential than its solution, which the philosophy of Lean helps you to do.38

The philosophy of Lean truly excels at asking the best open-ended business questions to discover the highest value. Since all problems are solvable within the universal value stream,39 Leanism allows you to properly infer and deductively question the meaning of and correlations within data as it applies to consumers’ lives and existences. Leanism bridges gaps in business analysis so you may ask beautiful questions and answer wicked problems with what good data you can obtain.40 To reach the greatest profit, you ask the biggest questions to reach the deepest problems you can find that customers will pay you to resolve. Thus, Leanism’s Socratic method represents a form of Design Thinking by leading with empathy and crossing all business disciplines within the U/People business model. This allows an organization to wholly identify why, what and how consumers will buy goods and/or services. You ask “who” to maintain an empathetic customer-centeredness, “why” to define problems, pierce ambiguities and achieve more “AHA” moments, “what” to ideate and produce, and “how” to prototype and test really tangible benefits that may be exchanged for money.41

Thus, by normalizing how you discuss true-north value across an organization through “Design Thinking,” “Systems Thinking,” and altogether “Lean Thinking,” you can better connect all topics and disciplines to holistically identify and quantify how you can meaningfully make the most money by doing good from analyzing the data you have well. For example, of any business fields, finance excels at gathering and synthesizing big data sets, and yet, finance still shows limited (though still highly lucrative) success in accurately predicting true-north value creation.42 As I hope you will see, all financial analysis boils down to philosophical perspectives as well and could be improved through these same Socratic methods.

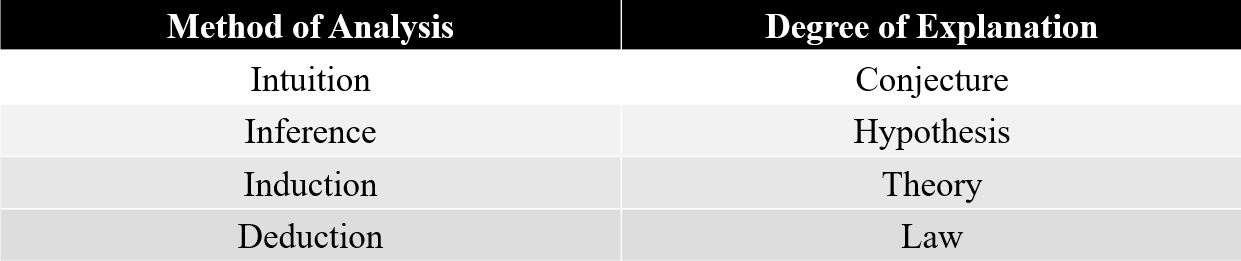

Every organization must ask beautifully inspired intuitive, inferential, inductive and deductive questions43 to create true-north value with either a lot, little or no data by knowing why and how its business leans toward who consumers truly are.44 Once a business determines who its customers are or who they ought to be mostly by what they do, it then can relate why consumers value those activities to what it can satisfy them with the most. It deduces what metaphysically related products and/or services, functions, features or benefits consumers will actually buy. This allows a business to better hypothesize how to make the most meaningful amounts of money by identifying and relating these metaphysical factors to consumers’ lives and existences to enter, expand or create new markets. This process will naturally transform an organization’s upper-management into chiefly functional, meaningful and innovative officers. Once this is done, its HQ will uniquely/profitably extend and optimize consumers’ lives and existences from analysis to execution.

Why Lean More Specifically?

You lean in business by developing customers to consume products and/or services that you efficiently reproduce in exchange for the money on which every corporation’s very existence and identity depends. Given the basic use of Lean principles in business, let’s look at the common definitions of Lean to understand why the term “Lean” philosophically applies to business. And since the formal use of Lean as a business term is relatively new in the history of the English language, I suggest that you ought to use all of its ancient meaning as a vehicle for a people-oriented, business ideology to pursue the greatest profit.

In the common vernacular of Old English, the Oxford English Dictionary defines “Lean” as “Reward, recompense,” which accords with the modern spelling of “Lien” as meaning a right to a debt to be repaid in exchange for a product and/or service that has been provided. A Lean business owes its customers and society at large true-north value for the money it charged, deducted and now gets to redistribute to shareholders, employees, contractors, vendors, philanthropies and politicians.

The Oxford English Dictionary also defines “Lean” as, “The act or condition of leaning; inclination.” This definition means that whatever or whoever leans, does so against something or someone else, just like how any business organization fundamentally supports itself by leaning on its paying customers, and just like how shareholders do in-turn by leaning on the organizations in which they invest.

Lastly, the Oxford English Dictionary defines Lean as, “Wanting in flesh; not plump or fat; thin.” This definition indicates that whatever or whoever is lean efficiently processes energy, much like any effective organization maximizing stakeholder value; however, this definition of “Lean” does not mean gaunt, but rather athletically tautological as you will see.

With all this intellectual heritage, Lean can be summarized in formal terms as meaning the creation of “value” by removing waste from an organization’s production system on which stakeholders depend. Any waste that does not create true-north value is referred to in Lean as “Muda” (無駄). The other forms of Lean waste are “Mura” (斑), meaning any unproductive variance in reproduction such as those caused by bad performance metrics so often employed by companies, and “Muri” (無理), meaning waste caused by overburdening production systems and not fully respecting people. This Lean legacy of waste avoidance can be traced to the Buddhist and Shinto concept of Mottainai (もったいない), which is a term of Japanese origin meaning to reproduce, re-use, recycle, and reinspect wherever possible. Leanism synthesizes these forms of waste by defining Lean waste as activities that do not reduce consumers’ existential pains.

Lean, like most business theories, determines what most profitably satisfies the most customers and how to do that best. Like the formal discipline of “Lean” in quotes, the U/People business model directs you to bow from within an organization’s HQ toward uniquely/profitably extending and optimizing consumers’ lives and existences by solving their greatest problems for a profit.45 The world’s largest companies lean philosophically in this way, since “Lean” is, as we have discussed, also a term-of-art commonly used in business to mean a set of principles organized from studying of what made the Toyota Motor Corporation so successful for so long by being amazingly prophetic about the future of the automobile industry.46

Academics have further developed and defined Lean principles. James Womack and Daniel Jones in their well-regarded 2010 book, “Lean Thinking,” established the five fundamental principals of Lean as:

- Identify value: “The critical starting point for lean thinking is value…Value can only be defined by the ultimate customer. And it’s only meaningful when expressed in terms of a specific product (a good or a service, and often both at once) which meets the customer’s needs at a specific price at a specific time”; 47

- Identify value stream: “The value stream is the set of all the specific actions required to bring a specific product (whether a good, a service, or, increasingly, a combination of the two) through the three critical management tasks of any business…problem solving…information management…and the physical transformation”;48

- Flow: “In short, things work better when you focus on the product and its needs, rather than the organization or the equipment, so that all the activities needed to design, order, and provide a product occur in continuous flow”;49

- Pull: “You can let the customer pull the product from you as needed rather than pushing products, often unwanted, onto the customer”; and

- Perfection: “As organizations begin to accurately specify value, identify the entire value stream, make the value-creating steps for specific products flow continuously, and let customers pull value from the enterprise, something very odd begins to happen. It dawns on those involved that there is no end to the process of reducing effort, time, space, cost, and mistakes while offering a product which is ever more nearly what the customer actually wants. Suddenly perfection, the fifth and final principle of lean thinking, doesn’t seem like a crazy idea.”50

While Krafcik, Womack, Jones and others established Lean as a business discipline following Krafcik’s coining the term, a lot more has been written about Lean processes and application to making money since then, even if not a lot has been written regarding “Lean Thinking’s” item number (1) Identify Value. For example, the entrepreneur Eric Ries applied Lean to early stage product and/or service development by coining the term, “Lean Startup,” in his same titled book, “The Lean Startup.” Ries described how he built an online avatar business, “Instant Message Virtual Universe” (“IMVU”), through iterative user testing. However, Ries’ para-scientific, “Build-Measure-Learn” methodology focused entirely on people’s revealed preferences without philosophically identifying the meaning of the data being received from end-users. Observing what people do and the how they pay for it follows a process of trial and error correction, but without any guiding insight as to what to ask and how to identify meaningful revelations. This leads to waste and missed commercial opportunities.51

Thus, despite Lean’s various applications to date, very little has been written to fully identify true-north value, other than this iterative process of offering minimally viable products and/or services to see what consumers purchase. This is because people have somewhat ignored the historical and philosophical legacy of Lean that consistently points in the proper direction. By better understanding the history and philosophy of Lean, organizations may quickly apply Lean to all their operations, while improving their insights with market testing. For example, people ought to know the origin of the Lean Japanese term “Jidoka” (自働化) to apply Lean best. Jidoka originated from Sakichi Toyoda, the founder of the Toyota Group, when he installed a device called a “jido” on an automatic textile loom that allowed human operators to make autonomous judgments to improve production.52 Jidoka is thus a historical process of human trial and error correction in the context of the industrial revolution, which Toyota has now modernized to mean automation with a touch of guiding human knowledge.53 True-north value identification through Jidoka comes from the integration of human philosophical insight (in Lean terms, “Genchi Genbutsu” (現地現物)) and error correction (in Lean terms, “Poka-Yoke”) to create the greatest true-north value for consumers. Jidoka is the best measure of quality that any Lean system of management can apply as it iteratively tests whether its products and/or services fit its markets well.

As you extend the iterative process of Jidoka out toward consumers and business in general, you ought to:

- Follow the Western philosophical tradition of empathizing who consumers truly are called “Phenomenology” (which is best described in Lean terms again as, “Genchi Genbutsu”);

- Conjecture, hypothesize, and theorize what creates the most true-north value for them with your guiding intellect (which is best described in Lean terms again as, “Jidoka”); and

- Then criticize through market tests whether a solution provides at least an adequate profit (which is best described in Lean terms again as, “Poka-Yoke”).

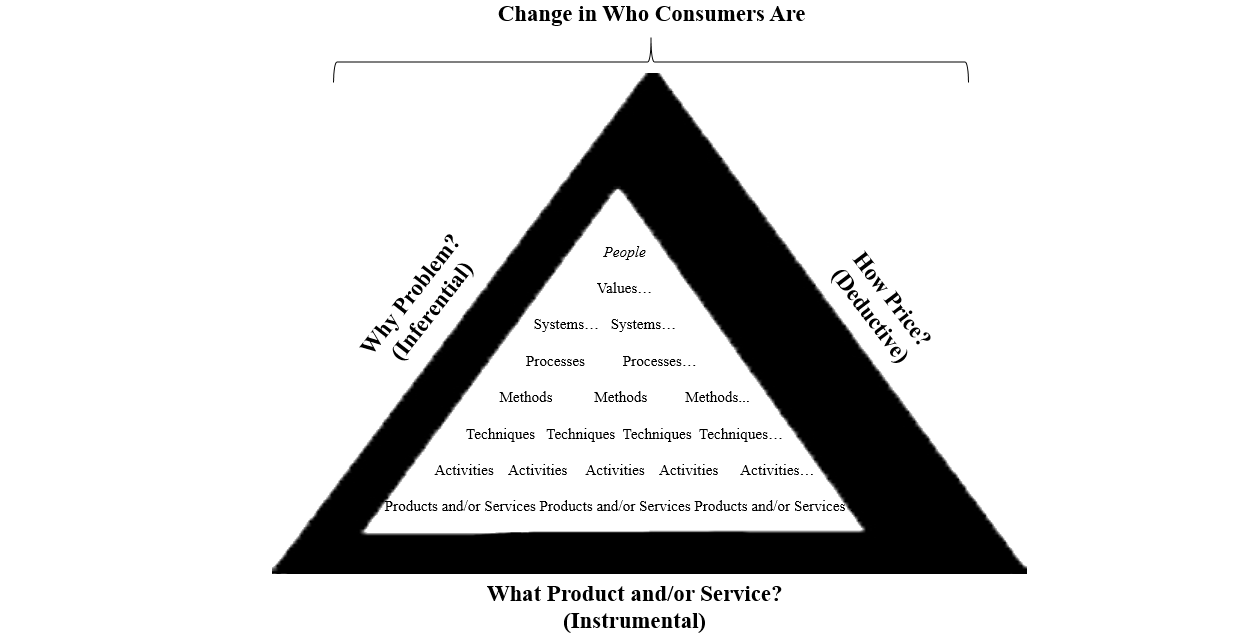

Thus, to align value streams toward a horizon of commercial possibility, you must fully lean toward consumers by empathizing with the best evidence you can gather from the start. Then, from this universe of empathy, you relate the unlimited problems consumers have to the price you may charge them for their resolution. The Japanese company Nissan reflects this notion in its implementation of a variety of Lean called, “Nissan Production Way” (“NPW”). NPW pursues the “Two Neverendings” of: (1) “Douki-seisan” (同気生産)) which is a perpetual synchronization with the customer, and (2) the, “never ending quest to identify problems and put in place solutions” for a price.54 You can see where the value streams of problem and price meet at the point of empathy with the customer in the logo for Nissan’s luxury car brand, Infiniti:

Leanism’s four primary interrogatories of who, why, what and how complement the never-ending, iterative development processes of Kaizen and Jidoka by uniquely guiding product and/or service ideation, innovation, design and monetization.55 These lean interrogatories will lead you toward products and/or services that are practically useful, aspirational and profitable. I summarize the Socratic questions of who, why, what and how in the shorthand form of “3WH.” Since these interrogatories are critical to the philosophy of Lean, here are their definitions from the Oxford English Dictionary:

- Who, pron. (and n.), As the ordinary interrogative pronoun, in the nominative singular or plural, used of a person or persons: corresponding to “what” of things;

- Why, adv. (n. and int.), In a direct question: For what reason? From what cause or motive? For what purpose?;

-

What, pron., adj., and adv., int., conj., and n.:

1. As the ordinary interrogative pronoun of neuter gender, orig. sing., in later use also pl., used of a thing or things: corresponding to the demonstrative “that”;

2. Of a person (or persons), In predicative use: formerly generally, in reference to name or identity, and thus equivalent to “who”; in later use only in reference to nature, character, function, or the like; and - How, adv. and n., Qualifying a verb: In what way or manner? By what means?

Notice that the interrogatory “what” flows through all these definitions, and that “who” and “what” are essentially equivalent by their reciprocal references to one another in their above definitions. All of the 3WH interrogatories are interrelated to derive “what” matters most as a whole in ontological, and thus metaphysical terms, much like the four interlocking rings of the Audi automobile logo:

By following these interrelated, four-word steps of 3WH, you will consistently reach epiphanies about what you ought to produce to most uniquely, profitably extend and optimize consumers’ lives and existences in all commercial environments.56 However, instead of only reviewing what consumers say or reveal, Leanism’s 3WH method of analysis abstracts Lean value theory toward philosophically framing true-north value in life and business within which all consumers’ preferences best fit. 3WH is a reformation of true-north value when you recognize that consumers ultimately seek true-north value beyond what is immediately known. Thus, the power of a Lean business ideology is to apply this abstract knowledge to identify specific solutions across all business problems you may face.

Leanism, through the 3WH process, makes Lean applicable to all aspects of business by further intersecting Lean with the Western study of true-north value called “Axiology.” Axiology may be considered the combination of what attracts consumers to buy through aesthetics, and what consumers ought to do through ethics. The Japanese term, Kinobi (機能美) standing for the principle that aesthetics (and by extension ethics) equate with utility, is used in Leanism to channel both sides of Axiology through sound Lean value theory within business to help you make money meaningfully.

Philosophically Leaning Your Business Ideology

Those attempting to philosophize like me often paraphrase the famous 20th Century mathematician and philosopher Alfred North Whitehead57 as saying that the whole of Western philosophy was, “… a series of footnotes to Plato.”58 Whitehead captured the notion that trying to build a true-north value theory is like attempting to add your own deeply buried footnotes to countless thinkers before. Similarly, you lean metaphysically by collecting ideas together and applying them within your own context. You use Lean as a vessel to navigate through channels of timeless value streams.

By explaining who consumers are, and why and what they most value, Leanism enhances the art and para-science of business. Like Eric Ries described with his, “Build-Measure-Learn” methodology in “The Lean Startup,” business as a whole is a para-science because while science tests the causes of various effects, the desired effect of producing a profit in business is plainly obvious.59 The challenge is causing such a financial outcome by universalizing true-north value for consumers as exceptionally complex people. You as a businessperson have the difficult task of optimizing consumers’ standard of existence to the greatest extent in all domains, leaving neither markets untapped nor money on the table.

Philosopher Kings and Queens

As Jim Collins wrote in “Good to Great”, “The good-to-great leaders… They are more like Lincoln and Socrates than Patton or Caesar.”60 World famous business people today most often describe their own, “business philosophies,” with modern philosophical and scientific principles. For example, the famous entrepreneur Elon Musk advocates for all people to reason from first principles when he said during a 2012 interview,

First principles is kind of a physics way of looking at the world. You boil things down to the most fundamental truths and say, ‘What are we sure is true?’ … and then reason up from there.

However, none of these business people seem to provide other people with a way to think effectively from first principles without thoroughly educating themselves in esoteric philosophy and similarly dense subjects – this Leanism book is enough! Thus, business philosophy often devolves either into vague aphorisms that do not lend themselves to functional analysis, or into logically weak insights that eventually become entangled in their own reasoning when rigorously applied, leaving other business people frustrated when trying to borrow from these billionaires’ brilliance.61

However, quite a few examples of rigorously philosophical billionaires exist. Billionaire trader George Soros writes with diligence and vigor when describing his philosophical concept of “Reflexivity” in his 1983 book, “The Alchemy of Finance.” You can also see Soros’ concept of reflexivity in Alfred North Whitehead’s and Nicholas Rescher’s, “Process Philosophy.”62 Carl Icahn earned a B.A. in philosophy at Princeton, having written his senior thesis about the definition of meaning from the empiricist tradition.63 These philosophical concepts from Soros and Icahn even play themselves out in the tautological economic models of Revealed Preference Theory proposed by Herbert Simon, which is widely used by mainstream economists today.

For further examples of self-made philosophical billionaires, Dr. Patrick Byrne, founder of Overstock.com, earned a Ph.D. in philosophy from Stanford University. Reid Hoffman, founder of LinkedIn, earned a masters degree in philosophy at Oxford before joining Apple.64 Michael Bloomberg studied philosophy at New School after graduating from Harvard Business School.65 Steve Jobs, CEO and one of the principal founders of Apple Inc., studied, practiced and was influenced by the Eastern religious philosophy of Zen Buddhism.66 Ray Dalio, founder of Bridgewater Associates, described his value theory in his manifesto, “Principles,” where he begins by instructing all to start their business analysis by asking the epistemological and ontological question, “Is it true?” like Elon Musk.67 Apple Inc. espoused this epistemological sentiment when the company designed its logo to be a piece of fruit from the tree of all knowledge with a byte taken out of it.68

While each of these business people lean philosophically in some way, try as they might none provides a broadly applicable, logical framework for organizing the first principles of the human condition from which all meaningful true-north value, and thus all consumer demand, ultimately originates. Business people write business books that invoke philosophy, but what may be more helpful in making real progress is a philosophy book about business, particularly one that places the philosophy of science at its core while synthesizing ancient wisdom through the modern business discipline of Lean. I present what I consider to be the philosophy of business within the paradigm of Lean, and hope to channel the thoughts of these great leaders for you to lean an organization’s business philosophy forward in their homage.69

Supporting this approach, Collins and Porras in “Built to Last” stated, “Contrary to popular wisdom, the proper first response to a changing world is not to ask, ‘How should we change?’ but rather to ask, ‘What do we stand for and why do we exist?”’70 Collins and Porras described their pragmatic idealism as one that companies built to last use in the Yin and Yang symbols, adapting while preserving core values and purposes around a figurative fly wheel.71 Steve Jobs said when introducing the “Think Different” advertising campaign to Apple employees:

All these great business leaders propose a Yin/Yang approach to business, mixing oriental with occidental philosophies together as a business ideology to make money consistently. Thus, oriental religious philosophies, like Confucianism, Shintoism and Buddhism, combine in tension in a Yin/Yang with the occidental Philosophy of Science and Western consumerism to great effect. Lean is a philosophy of business grounded in ancient wisdom while always changing in the face of new demands and discoveries. Likewise, Lean is the existential core of every business, and what essentially changes is its implementation. Or, to paraphrase Aristotle from the 4th century B.C.E., “[Lean] philosophy begins in wonder, seeking the most fundamental causes or principles of things, and seems the least necessary but is in fact the most divine of [business] sciences.”73 Or, as Marcus Aurelius more recently said in 167 A.C.E., “No [organizational] role is so well suited for [Lean] philosophy as the one you happen to be in right now.”74 [the bracketed additions are my own of course].

By going beyond what a company certainly knows, the philosophy of Lean can help an organization determine what ought to be its core true-north values whatever it decides best extends and optimizes all people. Alfred North Whitehead, the previously referenced philosopher and mathematician who wrote “Mathematica Principia” with Bertrand Russell, said, “Philosophy is the critic of cosmologies, whose job it is to synthesize, scrutinize and make coherent the divergent intuitions gained through ethical, aesthetic, religious, and scientific experience.”75 I would add that the philosophy of Lean also upends false assumptions and enhances a business’ perspective to guide an organization’s quantitative and qualitative insights into what consumers and all stakeholders find most meaningful.

Going one step further, Greek philosophers such as Cynics, Skeptics, Epicureans and Stoics analyzed: (1) what was truly valuable and what was not, and (2) how one could find true-north value and protect oneself against longing for false, valueless things.76 Further in time, the Roman Cicero said that, “To study philosophy is to prepare oneself for death.” This means that you ought to use the philosophy of Lean to discover what consumers truly value for the most meaningful amounts of money before a business meets that same fate.77 Thus, I hope you agree that the philosophy of Lean is the formal study of true-north value in life and business, and that the exchange of Lean value for money is (or perhaps ought to be) all organizations’ ultimate source of viability.

In the end, Leanism does not see philosophy so much as a means toward an independent truth (though philosophy can be a leading indicator for science), but more as an effective way to bridge your understanding of consumers’ personal perspectives with what you know about them from math and science, or otherwise emotionally intuit.78 Philosophy in this way helps guide you toward best satisfying consumers’ basic needs so they will be shattering the doors of stores to become customers!

The Philosophy of Lean in the Grand Design

However, to make clear philosophy’s role in analyzing true-north value, let’s play devil’s advocate with the great, late Stephen Hawking. Stephen Hawking was a famous theoretical physicist, who once derided traditional philosophy as having lost its ability to answer the bigger questions of existence given recent scientific advancements toward that goal.79 He said that philosophy has nothing to say regarding the origin of what consumers most truly value, and thus says nothing about how an organization may make money meaningfully.80

Presuming for argumentative purposes that Stephen Hawking was and still is correct, which he could very well be, and theoretical physics succeeded philosophy (and religion for that matter) as the tool with the greatest explanatory power for consumers’ lives and existences, I propose that philosophy’s rigorously analytical tools developed by tremendous minds over millennia can and ought to be repurposed to frame the analytical questions of what Lean true-north value in business is so it can be most effectively monetized by you. Summarized well, philosophy can structure products and/or service innovation and guide business processes toward profitable and ethical success to make meaningful amounts of money over generations, which is all that truly matters to the ultimate viability of an organization.

In sum, mathematical, scientific, philosophical and intuitive insights into who and why consumers are provide the logical underpinnings of Lean true-north value theory, and thus, the foundation for organic growth. The philosophy of Lean acts both as the middleware between an organization’s scientific and intuitive business analysis, and helps you identify true-north value at the intersection all reason and speculation. By implementing these insights, an organization will make money meaningfully when the currents of science, economics and philosophy intersect at the fjord of satisfaction that products and/or services ought to produce for consumers. Leanism thus approaches Lean true-north value from its very inception and streamlines it for business success.81

So while modern philosophy and the rest of the humanities respect mathematics and scientific knowledge as the most widely shared and predictable true-north values, the humanities still function to illuminate and speculate what are the overall ultimate processes leading to consumers’ lives and existences and the associated meaning their lives may have. In the end, the humanities inform the existential limits an organization and consumers inevitably run into, bounded by their ignorance, circularities, infinities and paradoxes.82 No matter how intelligent they are, consumers and organizations are surrounded by marginal event horizons and cosmic censorship, left only to hope for something more. Where neither science nor philosophy fully informs who consumers are and why they buy products and/or services, consumers’ individual agnosticism, intuitive spiritualism or speculative scientism fulfills the third rail in businesses’ value worship. As Steve Jobs famously said,

Part of what made the Macintosh great was that the people working on it were musicians and poets and artists and zoologists and historians who also happened to be the best computer scientists in the world.83

From the modern, post-modern, or post-post-modern (sometimes referred to as “pseudo-modern” or “meta-modern”) perspectives, you can see levels of validated, commonly shared beliefs about consumers’ reality in the golden braid of mathematics, science, philosophy and intuition. These domains identify Lean true-north value with decreasing levels of common agreement among all potential customers as you move up the universal value stream:

Mathematics and science provide the most technically validated and commonly agreed forms of information.84 On the other end of this spectrum, religious, spiritual and scientismic intuition fills a void where science and philosophy do not qualify as commonly agreed values. Consumers realize these latter forms of true-north value by what they intuitively/religiously/spiritually/scientismically speculate, even if what they believe is not commonly held by all people. In contrast, philosophical principles function as abstractions that may be used to reach better solutions to business problems by seeing through to the truth (“Is it true?”) underlying all technical detail. The Lean business philosopher thus ought to have a competitive advantage to more effectively reproduce and monetize true-north value for this reason. So, you will walk away from this text with new, Lean philosophical acronyms and analogies that you may use as rules of thumb to monetize meaning regardless of the origin of your ideas.

An excellent question exemplifying a point where science, philosophy and intuition intermix to determine what consumers most truly value is, “What created natural, physical laws, consumers, and the universe in the first place?” This question is represented by the question mark “?” at the beginning and end of the above value stream running through fields of inquiry. I’m sure consumers have some intuitive belief, faith, or agnosticism marking that question, and their attitudes toward it particularly determine why, what, and how they purchase. Let’s look at this question briefly from the respective perspectives of science and religion to see what role the philosophy of Lean plays in mediating between these fields today to identify true-north value and the secret meaning of money as we move along all fields of knowledge to reach the greatest profit.

Science

Physicists generally attempt to describe the origin of consumers’ existences, and thus all true-north value, by statistically analyzing theories, or they theorize classical notions of what the universe is or is not to get to that same point. Scientists generally make these physical explanations for why consumers exist intentionally circular since they base these explanations on physical laws of unknown origin.85

For example, a certain classical theory in vogue is multi-verses specifying that the universe consumers personally know is one of an infinite number of them, and they are but one variation of infinite possibility. The laws in such universes are randomly created with whatever probabilities might exist in such warped domains. Within some variations of this theory, each black hole holds a universe unto itself, each with its own variation of the laws of physics. Another theoretical variation demonstrates the multi-verse by explaining quantum mechanics itself as a consequence of the coherence and discoherence of the subatomic units of parallel universes within the multi-verse. These theories hold that each parallel universe is well designed in its own unique way while remaining fungible at its most basic level, much like the multiple meanings simultaneously arising from the homonyms, symbolism and acronyms.86

Alternatively, consider that if consumers could see past the limit of the speed of light racing toward them from the edges of the known universe, they might find further cosmoses within the same spacetime continuum if only they could lean far enough to see them. Finally, if you project far enough into the future, you might conclude that video games, like Eric Ries’ Instant Message Virtual Universe, or The Sims, would improve to such a degree with each new version that this universe you know so well might itself be a simulation.87 We might be characters within IMVU at this very moment. Who is winning?

While these scientific theories are all grand, consumers must recognize that no such purely physical or computational theory to date conclusively answers in non-circular fashion why the physics (or programs) guiding their lives exists at all- what explains why anything exists at all, and thus why consumers live and buy anything at all other than to subsist. The ongoing faith an organization has that consumers will find the products and/or services it provides truly valuable leaves open all forms of intuitive speculation by upper management.88 Ultimately, consumers’ true religion is hard to define, but Leanism diagrams its contours for you as you will see below.

Religion

To begin understanding what creates Lean true-north value, you cannot ignore the very personal topic of religion. It must be discussed for this conversation to be complete. To address it head on for your Lean business ideology, look at one of the most widely adopted academic definitions89 of religion that was proposed by the anthropologist Clifford Geertz. Geertz described religion as a system of symbols that acts to:90

- Establish powerful, pervasive, and long-lasting moods and motivations in people;

- Formulate conceptions of a general order of existence;

- Give these conceptions an aura of factuality; and

- Make these moods and motivations seem uniquely realistic.

Not coincidentally, Geertz’s definition of religion leans a business metaphysically through the 3WH value creation interrogatories of who, why, what, and how. Like the four parts of Geertz’s definition, consumers’ true-north values determine:

- Who consumers are as emotionally motivated people;

- Why consumers buy products and/or services to better exist;

- What consumers conceive as factually valuable; and

- How consumers really get uniquely and emotionally motivated to buy products and/or services with money.

Thus, religion, just like science, also seeks to answer who, why, what, and how, except with intuitive speculation rather than scientific investigation. “Why” in religion speculates a general order of existence from a higher power, while “what” grounds religion in the soil of experience by what people actually believe. “Who” in religion divines who people are by which deities they ultimately follow, while “how” in religion determines the beliefs held, rituals followed, sacrifices made, indulgences paid, or lives lived to reach Nirvana. We will explore further these 3WH interrogatories as you proceed up through the U/People business model with a religious devotion to all consumers whatever they may believe.

Limits to Business Quantification

You as a business person reasonably tend to rely heavily on the quantifiable aspects of true-north value measurement, such as with accounting, finance or econometrics. Monetary or other quantitative measurements provides a fairly uniform way to discuss business processes globally. However, the common expressions, “Not everything that counts can be counted,” and, “Businesses measure everything and understand nothing,” articulate the fact that, significant, unresolved, and often under-appreciated limits exist in money’s ability to quantify and measure what people truly find meaningful in an absolute sense. In the difference between science and religion, you come to the natural limits of what the four-step Lean 3WH value interrogatories can quantify and predict since no one has a firm grasp on what permits or limits open-ended, infinite intuitive, spiritual, scientific and/or religious speculation.91

Leanism will clarify and explain those limits more precisely for understanding exactly what money and other metrics do and do not measure and mean. Understanding the difference will not only improve a business for societal profit, but will also improve financial profits by taking you to the edge of what an organization can monetize so you can focus on what you have reason to believe is most profitable.92 The difference between making meaningful amounts of money and making money meaningfully is that while the former immediately satisfices, the latter allows you to achieve greatness and build a company that will carry your legacy onward and upward.

So while money reasonably accurately quantifies people’s preferences, accounting, finance and econometrics cannot entirely direct research, development and marketing toward what best satisfices and optimizes consumers – many things are difficult to measure well, due to incomplete information and knowledge, which are often referred to as business intangibles. In fact, the more knowledge we as people have and apply toward our own ends, the less we can predict the future.93 Thus, despite very well developed financial measures and operational metrics, businesses still pray for epiphanies as to what meaningfully making money means through the Lean value stream, and how such insight might further guide quantitative analysis toward blue oceans of profit in an unchartered universe.

The U/People Business Model

By constructing a comprehensive true-north value theory to apply Lean thinking to an organization, you ought to be able to understand the context in which an organization measures true-north value for all of its stakeholders regardless of their religious beliefs. By all stakeholders, I mean customers, employees, board members, shareholders, and/or society. Thus, a Lean business ideology ought to be a universal system of thought grounded in true-north values, but also related to the apparent paradoxes inherent in all stakeholders’ lives and existences. It ought to bring together a wide range of ideas and disciplines in a unified structure for analyzing and predicting what all stakeholders find most truly valuable and therefore will want to buy.

By way of example of Leanism’s flexibility for building a meaningful true-north value theory, references to businesses, corporations, or organizations may likewise be read throughout this book to include governmental or not-for-profit entities. You can replace “customers” with taxpayers, donors, or congregants, since they are all ultimately “consumers” of existential solutions. For example, in the charitable context, charitable recipients and society are the indirect beneficiaries of charitable activities. Charitable beneficiaries are part of the products and/or services actually sold to donors. Donors in-turn indulge in the satisfaction of, possibly receive some prestige for, and certainly universalize their influence as a result of naming buildings and institutions after themselves.94 That is a very real way to look at the business of charity, but making abstract theory really applicable to what consumers most truly value is why you lean philosophically toward people.

Synthesizing Subjects

Hopefully, given this introduction to Leanism thus far feeding a Lean analysis of what matters most to stakeholders, you can appreciate how an overarching true-north value theory that philosophically organizes business information ought to be useful to you. Quite commonly, researchers at the highest levels of different fields independently examine the same concepts from different perspectives within their own disciplines. Authors generally write in one discipline or another without interrelating their disciplines to others with which their domain of expertise intersects. However, as you have seen, the philosophy of Lean will help you do just that for remarkable business insights.

For example, as Fred Gluck, the founder of McKinsey’s strategy practice, said that strategic planning is an exercise in continuously evolving the most effective rules of thumb that yield the greatest business results.95 Philosophical metaphysics and strategic metadata create these rules of thumb exceedingly well if brought down to Earth. For example, consider all knowledge from the top down. Philosophy was the intellectual parent of modern physics, which in turn determines chemistry, which informs biology, which affects psychology, which combines chemistry and biology into psychopharmacology that can change who consumers are and their philosophical perspectives on life and existence. At some point, all these fields of knowledge intersect and inform one another in circular fashion, since all academic subjects ultimately reduce themselves toward the goal of best understanding and improving consumers’ lives and existences, which is philosophy’s ultimate domain of inquiry as well.

Steve Jobs consistently said as much, as further evidenced by his interview with the Smithsonian Institution on April 20th, 1995 while he was running NeXT Computer:96

I actually think there’s actually very little distinction between an artist and a scientist or engineer of the highest caliber… They’ve just been to me people who pursue different paths but basically kind of headed to the same goal, which is to express something of what they perceive to be the truth around them so that others can benefit by it.

However, the polymath- a person who could truly excel across multiple disciplines- is increasingly rare if not already extinct due to the fact that the quantity of knowledge needed to enhance any part of the body of knowledge of any given general field of knowledge stands beyond what any one person is currently capable of understanding in a lifetime.97 This has been truly said for some time, and will only become truer as our knowledge exponentially increases, and sub-disciplines of knowledge continually grow, while we increasingly rely on artificial intelligence to cross these domains.98

Making a genuine contribution of knowledge to any given subject these days consumes a person’s entire intellect and a lifetime of dedication, so seeing beyond existing knowledge and interrelating the collective body of knowledge in general, particularly in business, becomes increasingly difficult even as the information within sub-disciplines becomes more effective at addressing specific problems. This situation is sub-optimal for leaning an entire organization toward all that consumers most truly value because of the difficulty in knowing and synthesizing all this information intelligently.99

Leanism thus becomes a type of product and/or service of its own, a philosophical and pragmatic body of knowledge for a corporation, constituting the sum of the expertise that went into creating and aligning it with what consumers truly value, allowing you to lean across multiple disciplines, and ask AI better questions, to serve them best. Likewise, think about what consumers truly value when they employ chemical and mechanical engineers the next time they use a toothbrush. Think about the expertise of the aerospace engineers consumers hire the next time they fly. Consider the cumulative medical knowledge gathered through millennia of trial and error in the process of Jidoka and Kaizen that doctors currently lean on and re-transmit when a consumer enters a doctor’s office for a check-up.100

While Leanism provides this intellectual leverage, an organization will never make money rotely with the philosophy of Lean and the U/People business model.101 Even though Leanism is not a deductive formula for success, I guarantee that you will gain confidence from knowing when you are on the right path if you flow that embodied expertise about customers’ lives and existences through your own business ideology. You will have the confidence that you are providing the products and/or service you ought, which ought to produce for you the greatest profit of all.

For example, if making money meaningfully involves understanding consumers’ lives and existences, then even the financial industry can make more money by following these precepts when they intuitively understand the human condition and why people enter into economic exchanges to live and exist. While financial engineering does not require understanding people’s lives in all the ways described in this book, the negotiations and strategies used to execute financial transactions require understanding the counter-parties engaging in those transactions and all that they truly value, which the money being negotiated reflects.102 As another example, leverage aside, private equity does actually depend to a great extent on effectively operating companies as much as mathematically engineering their acquisition and divestment to produce financial gain.103 This means that even private equity firms and hedge funds must have a business ideology to understand what and how products and/or services get bought and sold to produce satisfactory returns most days.

While the U/People business model and acronym may describe what creates wealth and what you ought to lean toward in greater detail, and describes how wealth gets generated by higher order economic activity, it will fail to identify how to make money meaningfully in mechanical fashion, since money making is of course an open-ended endeavor.104 The philosophy of Lean is about your developing a value theory of continuously improving and pursuing perfection however unattainable it might be. The U/People business model by no means automates economic advancement, but it will provide you with a universal set of true-north values, processes, and methods to guide you to make the money you earn genuinely meaningful for everyone’s benefit.

Quantifying Lean Abstraction and Analogies for Sales Success

In addition to the foregoing benefits to studying Lean, the analogical (or dis-analogical) reasoning that is pervasive throughout the philosophy of Lean allows you to differentiate between partial and impartial truths that drive sales efficiency. Analogies, similes, metaphors, phrases, proverbs and fables all go into telling the sales stories of true-north value that get products and/or services bought and sold. You can in-turn use mathematics to produce precise descriptions, probabilities and measurements of these partial or impartial true-north values to determine the corresponding accuracy of analogies and similes in consumers’ minds. Examples include any time you compare a new business initiative to others and see the differences in how you served people’s true-north values from one period to the next. Once you identify the analogical comparables, you may ask questions like:

The philosophy of Lean provides a business ideology with tools to see the organic essence of any given situation and analogically reason from there to provide a greater return on customers’ investments in a product and/or service. True-north value originates from existential dichotomies in the difference between one period in time to the next, and how you reason analogically between those periods to identify and classify what has Lean value and what does not for consumers. This is especially true when comparing two different points in time from the present state to a future state, which lets you readily communicate and quantify the change in that true-north value to consumers.105 You lean metaphysically through a binary business ideology of what has true-north value and what does not toward an infinite sales potential.

From Zero to One106

Consumers make analogies and use binary computers to improve their human condition and better describe themselves in relation to what is or is not in the universe. In dichotomous fashion, they compute 1 as being not like 0 just like they self-reflexively identify their I as not being like not into infinite, counterfactual detail.107 In fact, consumers do this to determine how best to ontologically realize themselves being in the universe. Through the processes of time, however, the data of life and existence defines consumers and describes their behavior in some of these ways, which allows you to attempt to predict what consumers truly value. Both analogy making and mathematics converge to illuminate the fundamental, binary condition of consumers’ existence in all of its probability of “being” or “not being” to help you determine what might get bought by and sold to people.

Since Leanism improves analogical thinking, it also sharpens your business acumen by helping you make more sense out of markets, since abstract concepts in consumers’ minds shape their behavior, to which you can relate. The better you understand the abstractions consumers are thinking, the more fully you will be able to explain who consumers truly are.108 For example, the modern sociological researcher James Flynn, famous for the “Flynn Effect” demonstrating rising IQs across time, presented significant data showing that your own IQ score will increase once you increase your capacity to abstract and analogize between yourself and other people.109

As abstraction increases your own intelligence quotient, it likewise increases your appreciation of consumers’ and all other stakeholders’ IQs as well. Absorbing new true-north value streams grows your mindset110 toward abstracting a metaphysical business ideology to more intelligently serve your markets. Leanism is thus like the abstract artwork you pass by everyday in the hallways of an organization, which serves as a palette for your imagining ways to grow your future profits by meaningfully providing true-north value to customers.111

The U/People business model and acronym - Uniquely/Profitably Extending and Optimizing People’s Lives and Existences - and all the acronyms I use throughout this book, are acrobatic rules of thumb for you to use in a metaphysical business ideology to compress and unify widely divergent information together to lean toward consumers more profitably.112 The multiple definitions, word combinations, acronyms and phrases derived from Leanism’s meaning demonstrate that the business model’s concepts exceed the individual letters, symbols and words composing it, allowing you to reach across all value streams.113 At its very best, Leanism might even be analogized (or dis-analogized) to a long poem, since actual poetry represents the most compressed and extreme example of analogy making between concepts, thereby further abstracting and re-categorizing life, value and meaning for all people.114

You will in-fact find quite a bit of actual poetry interwoven throughout Leanism. With this, hopefully, you will see how analogy making is a powerful tool for abstraction that complements quantification to guide an organization’s faith toward better learning, understanding and predicting what really works.

For example, much of the premium you place on an employees’ work experience originates from their generally large set of examples of past problems, failures and solutions so they may efficiently analogize toward an iterative, Lean solution to present business problems. A business ideology will allow you to better see how employees lean their past experiences toward solving consumers’ problems by serving their fundamental true-north values. Think of the last time you were at work or took a test and you recognized familiar problems and were able to more effectively propose solutions or answers – that is how you analogically lean philosophically.

Analogy making from past experiences particularly relates to the details of the industry in which you operate. Look at how an organization asks interview questions of candidates’ past experiences, like the Gallup-style tests for employee selection repeatedly questioning interviewees from different perspectives.115 Look also at the interaction of qualitative and quantitative analysis when employers decide who to hire based on their own past experience within an industry. Analogy making is especially important in day-to-day situations in organizations that seek to continually improve, and a true-north value theory enhances an organization’s ability to analogize when it does not have the ability to quantify every decision.

The Symbols - The Forward Slash, Circumflex, and Sigmas

To facilitate the highly conceptual and artistic nature of this discussion, you will notice some instances where I use homonyms, homographs and homophones, and refine standard English with additional symbolism as listed in the Glossary. For example, I use the forward slash / to mean Lean, which is a segment of the spiraling value curve of the ontological teleology. I use this symbolism because while I write in American English, you lean philosophically in a sign-language that all consumers comprehend, such as through the trademarks that businesses use.116

I look to reveal the implicit meaning within the words we use in business every day regardless of whether a word’s etymology explicitly supports that meaning. So, using symbols like “/” will likewise help you universally improve the lives of all people for a profit. I also hope to reveal how business vocabulary itself guides the direction of true-north value when you pause for a moment to examine and deconstruct it carefully.117 As the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein wrote in 1953 at paragraph 129 of his, “Philosophical Investigations”:

The aspects of things that are most important for us are hidden because of their simplicity and familiarity… — And this means: we fail to be struck by what, once seen, is most striking and most powerful.