8. Typeclass Derivation

Typeclasses provide polymorphic functionality to our applications. But to use a typeclass we need instances for our business domain objects.

The creation of a typeclass instance from existing instances is known as typeclass derivation and is the topic of this chapter.

There are four approaches to typeclass derivation:

- Manual instances for every domain object. This is infeasible for real world

applications as it results in hundreds of lines of boilerplate for every line

of a

case class. It is useful only for educational purposes and adhoc performance optimisations. - Abstract over the typeclass by an existing scalaz typeclass. This is the

approach of

scalaz-deriving, producing automated tests and derivations for products and coproducts - Macros. However, writing a macro for each typeclass requires an advanced and experienced developer. Fortunately, Jon Pretty’s Magnolia library abstracts over hand-rolled macros with a simple API, centralising the complex interaction with the compiler.

- Write a generic program using the Shapeless library. The

implicitmechanism is a language within the Scala language and can be used to write programs at the type level.

In this chapter we will study increasingly complex typeclasses and their

derivations. We will begin with scalaz-deriving as the most principled

mechanism, repeating some lessons from Chapter 5 “Scalaz Typeclasses”, then

Magnolia (the easiest to use), finishing with Shapeless (the most powerful) for

typeclasses with complex derivation logic.

8.1 Running Examples

This chapter will show how to define derivations for five specific typeclasses. Each example exhibits a feature that can be generalised:

8.2 scalaz-deriving

The scalaz-deriving library is an extension to Scalaz and can be added to a

project’s build.sbt with

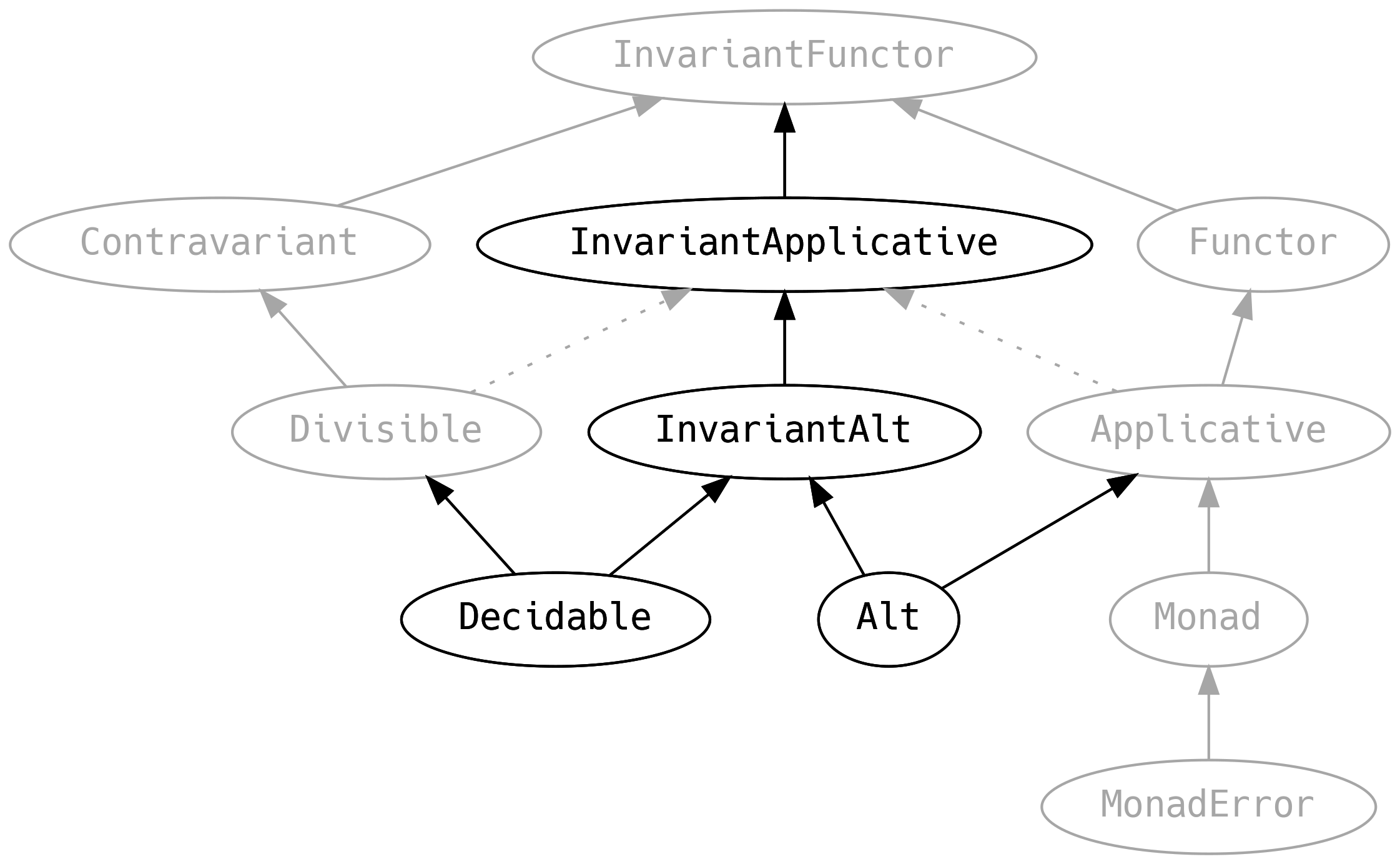

providing new typeclasses, shown below in relation to core scalaz typeclasses:

Before we proceed, here is a quick recap of the core scalaz typeclasses:

8.2.1 Don’t Repeat Yourself

The simplest way to derive a typeclass is to reuse one that already exists.

The Equal typeclass has an instance of Contravariant[Equal], providing

.contramap:

As users of Equal, we can use .contramap for our single parameter data

types. Recall that typeclass instances go on the data type companions to be in

their implicit scope:

However, not all typeclasses can have an instance of Contravariant. In

particular, typeclasses with type parameters in covariant position may have a

Functor instead:

We can now derive a Default[Foo]

If a typeclass has parameters in both covariant and contravariant position, as

is the case with Semigroup, it may provide an InvariantFunctor

and we can call .xmap

Generally, it is simpler to just use .xmap instead of .map or .contramap:

8.2.2 MonadError

Typically things that write from a polymorphic value have a Contravariant,

and things that read into a polymorphic value have a Functor. However, it is

very much expected that reading can fail. For example, if we have a default

String it does not mean that we can simply derive a default String Refined

NonEmpty from it

fails to compile with

Recall from Chapter 4.1 that refineV returns an Either, as the compiler has

reminded us.

As the typeclass author of Default, we can do better than Functor and

provide a MonadError[Default, String]:

Now we have access to .emap syntax and can derive our refined type

In fact, we can provide a derivation rule for all refined types

where Validate is from the refined library and is required by refineV.

Similarly we can use .emap to derive an Int decoder from a Long, with

protection around the non-total .toInt stdlib method.

As authors of the Default typeclass, we might want to reconsider our API

design so that it can never fail, e.g. with the following type signature

We would not be able to define a MonadError, forcing us to provide instances

that always succeed. This will result in more boilerplate but trades runtime

failure detection for compiletime safety. However, we will continue with String

\/ A as the return type as it is by far the more common use case.

8.2.3 .fromIso

All of the typeclasses in scalaz have a method on their companion with a signature similar to the following:

These mean that if we have a type F, and a way to convert it into a G that

has an instance, we can call Equal.fromIso to obtain an instance for F.

For example, as typeclass users, if we have a data type Bar we can define an

isomorphism to (String, Int)

and then derive Equal[Bar] because there is already an Equal for all tuples:

The .fromIso mechanism can also assist us as typeclass authors. Consider

Default which has a core type signature of the form Unit => F[A]. Our

default method is in fact isomorphic to Kleisli[F, Unit, A], the ReaderT

monad transformer.

Since Kleisli already provides a MonadError (if F has one), we can derive

MonadError[Default, String] by creating an isomorphism between Default and

Kleisli:

giving us the .map, .xmap and .emap that we’ve been making use of so far,

effectively for free.

8.2.4 Divisible and Applicative

To derive the Equal for our case class with two parameters, we reused the

instance that scalaz provides for tuples. But where did the tuple instance come

from?

A more specific typeclass than Contravariant is Divisible, and Equal

provides an instance:

And from divide2, Divisible is able to build up derivations all the way to

divide22. We can call these methods directly for our data types:

The equivalent for type parameters in covariant position is Applicative:

But we must be careful that we do not break the typeclass laws when we implement

Divisible or Applicative. In particular, it is easy to break the law of

composition which says that the following two codepaths must yield exactly the

same output

divide2(divide2(a1, a2)(dupe), a3)(dupe)divide2(a1, divide2(a2, a3)(dupe))(dupe)- for any

dupe: A => (A, A)

with similar laws for Applicative.

Consider JsEncoder and a proposed instance of Divisible

On one side of the composition laws, for a String input, we get

and on the other

which are different. We could experiment with variations of the divide

implementation, but it will never satisfy the laws for all inputs.

We therefore cannot provide a Divisible[JsEncoder], even though we can write

one down, because it breaks the mathematical laws and invalidates all the

assumptions that users of Divisible rely upon.

To aid in testing laws, scalaz typeclasses contain the codified versions of their laws on the typeclass itself. We can write an automated test, asserting that the law fails, to remind us of this fact:

On the other hand, a similar JsDecoder test meets the Applicative composition laws

for some test data

Now we are reasonably confident that our derived MonadError is lawful.

However, just because we have a test that passes for a small set of data does not prove that the laws are satisfied. We must also reason through the implementation to convince ourselves that it should satisfy the laws, and try to propose corner cases where it could fail.

One way of generating a wide variety of test data is to use the scalacheck

library, which provides an Arbitrary typeclass that integrates with most

testing frameworks to repeat a test with randomly generated data.

The jsonformat library provides an Arbitrary[JsValue] (everybody should

provide an Arbitrary for their ADTs!) allowing us to make use of scalatest’s

forAll feature:

This test gives us even more confidence that our typeclass meets the

Applicative composition laws. By checking all the laws on Divisible and

MonadError we also get a lot of smoke tests for free.

8.2.5 Decidable and Alt

Where Divisible and Applicative give us typeclass derivation for products

(built from tuples), Decidable and Alt give us the coproducts (built from

nested disjunctions):

The four core typeclasses have symmetric signatures:

| Typeclass | method | given | signature | returns |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Applicative |

apply2 |

F[A1], F[A2] |

(A1, A2) => Z |

F[Z] |

Alt |

altly2 |

F[A1], F[A2] |

(A1 \/ A2) => Z |

F[Z] |

Divisible |

divide2 |

F[A1], F[A2] |

Z => (A1, A2) |

F[Z] |

Decidable |

choose2 |

F[A1], F[A2] |

Z => (A1 \/ A2) |

F[Z] |

supporting covariant products; covariant coproducts; contravariant products; contravariant coproducts.

We can write a Decidable[Equal], letting us derive Equal for any ADT!

For an ADT

where the products (Vader and JarJar) have an Equal

we can derive the equal for the whole ADT

Typeclasses that have an Applicative can be eligible for an Alt. If we want

to use our Kleisli.iso trick, we have to extend IsomorphismMonadError and

mix in Alt. Let’s upgrade our MonadError[Default, String] to have an

Alt[Default]:

Letting us derive our Default[Darth]

Returning to the scalaz-deriving typeclasses, the invariant parents of Alt

and Decidable are:

Letting us write consistent boilerplate for all derivations:

This boilerplate also works when we have a typeclass like Semigroup that can

only provide an InvariantApplicative, not an Applicative.

8.2.6 Arbitrary Arity and @deriving

There are two problems with InvariantApplicative and InvariantAlt:

- they only support products of four fields and coproducts of four entries.

- there is a lot of boilerplate on the data type companions.

In this section we solve both problems with additional typeclasses introduced by

scalaz-deriving

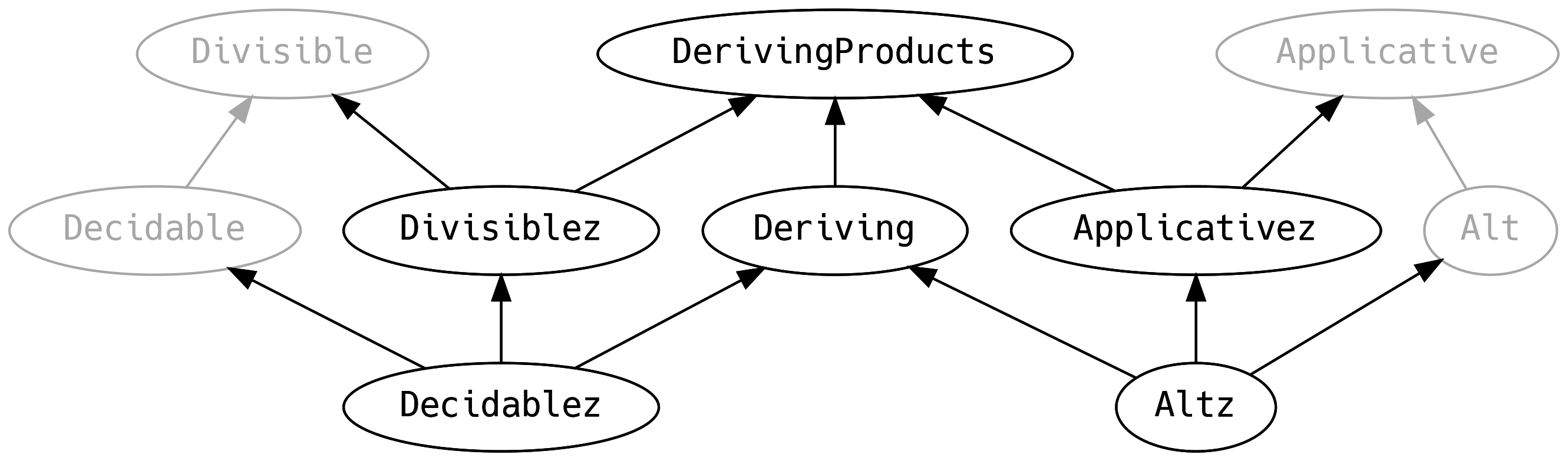

Effectively, our four central typeclasses Applicative, Divisible, Alt and

Decidable all get extended to arbitrary arity using the iotaz library, hence

the z postfix.

The iotaz library has three main types:

-

TListwhich describes arbitrary length chains of types -

Prod[A <: TList]for products -

Cop[A <: TList]for coproducts

By way of example, a TList representation of Darth from the previous

section is

which can be instantiated:

To be able to use the scalaz-deriving API, we need an Isomorphism between

our ADTs and the iotaz generic representation. It’s a lot of boilerplate, but

it pays off:

With that out of the way we can call the Deriving API for Equal, possible

because scalaz-deriving provides an optimised instance of Deriving[Equal]

To be able to do the same for our Default typeclass, we need to provide an

instance of Deriving[Default]. This is just a case of wrapping our existing

Alt with a helper:

and then calling it from the companions

We have solved the problem of arbitrary arity, but we have introduced even more boilerplate.

The punchline is that the @deriving annotation, which comes from

deriving-plugin, generates all this boilerplate automatically and only needs

to be applied at the top level of an ADT:

Also included in scalaz-deriving are instances for Order, Semigroup and

Monoid. Instances of Show and Arbitrary are available by installing the

scalaz-deriving-magnolia and scalaz-deriving-scalacheck extras.

You’re welcome!

8.2.7 Examples

We finish our study of scalaz-deriving with fully worked implementations of

all the example typeclasses. Before we do that we need to know about a new data

type: /~\, aka the snake in the road, for containing two higher kinded

structures that share the same type parameter:

We typically use this in the context of Id /~\ TC where TC is our typeclass,

meaning that we have a value, and an instance of a typeclass for that value,

without knowing anything about the value.

In addition, all the methods on the Deriving API have implicit evidence of the

form A PairedWith FA, allowing the iotaz library to be able to perform

.zip, .traverse, and other operations on Prod and Cop. We can ignore

these parameters, as we don’t use them directly.

8.2.7.1 Equal

As with Default we could define a regular fixed-arity Decidable and wrap it

with ExtendedInvariantAlt (the simplest approach), but we choose to implement

Decidablez directly for the performance benefit. We make two additional

optimisations:

- perform instance equality

.eqbefore applying theEqual.equal, allowing for shortcut equality between identical values. -

Foldable.allallowing early exit when any comparison isfalse. e.g. if the first fields don’t match, we don’t even request theEqualfor remaining values.

8.2.7.2 Default

We’ve already seen how to define an Alt and lift it to a Deriving with the

ExtendedInvariantAlt helper. However, for completeness, say we wish to define

an Altz directly.

Unfortunately, the iotaz API for .traverse (and its analogy, .coptraverse)

requires us to define natural transformations, which have a clunky syntax, even

with the kind-projector plugin.

8.2.7.3 Semigroup

It is not possible to define a Semigroup for general coproducts, however it is

possible to define one for general products. We can use the arbitrary arity

InvariantApplicative:

8.2.7.4 JsEncoder and JsDecoder

scalaz-deriving does not provide access to field names so it is not possible,

which is why we will study Magnolia in the next section.

8.3 Magnolia

The Magnolia macro library provides a clean API for writing typeclass

derivations. It is installed with the following build.sbt entry

A typeclass author implements the following members:

The Magnolia objects are:

with helpers

The Monadic typeclass, used in constructMonadic, is automatically generated

if our data type has a .map and .flatMap method when we import mercator._

It does not make sense to use Magnolia for typeclasses that can be abstracted by

Divisible, Decidable, Applicative or Alt, since those abstractions

provide a lot of extra structure and tests for free. However, Magnolia offers

features that scalaz-deriving cannot provide: access to field names, type

names, annotations and default values.

8.3.1 Example: JSON

We have some design choices to make with regards to JSON serialisation:

- Should we include fields with

nullvalues? - Should decoding treat missing vs

nulldifferently? - How do we encode the name of a coproduct?

- How do we deal with coproducts that are not

JsObject?

We choose sensible defaults

- do not include fields if the value is a

JsNull. - handle missing fields the same as

nullvalues. - use a special field

"type"to disambiguate coproducts using the type name. - put primitive values into a special field

"xvalue".

and let the users attach an annotation to coproducts and product fields to customise their formats:

For example

These user preferences also allow us to distinguish between null, missing and

valid values without any further modifications to JsValue, JsEncoder or

JsDecoder. For example, through this ADT

we can say that we require null values, otherwise using a default, then check

for null with Option:

Let’s start with a JsDecoder that handles only our “sensible defaults”:

We can see how the Magnolia API makes it easy to access field names and typeclasses for each parameter.

Now add support for annotations to handle user preferences. To avoid looking up the annotations on every encoding, we’ll cache them in an array. Although field access to an array is non-total, we are guaranteed that the indices will always align. Performance is usually the victim in the trade-off between specialisation and generalisation.

For the decoder we use .constructMonadic which has a type signature similar to

.traverse

Again, adding support for user preferences and default field values, along with some optimisations:

We call the JsMagnoliaEncoder.gen or JsMagnoliaDecoder.gen method from the

companion of our data types. For example, the Google Maps API

Thankfully, the @deriving annotation supports Magnolia! If the typeclass

author provides a file deriving.conf with their jar, containing this text

the deriving-macro will call the user-provided method:

8.3.2 Fully Automatic Derivation

Generating implicit instances on the companion of the data type is

historically known as semi-auto derivation, in contrast to full-auto which

is when the .gen is made implicit

Users can import these methods into their scope and get magical derivation at the point of use

This may sound tempting, as it involves the least amount of typing, but there are two caveats:

- the macro is invoked at every use site, i.e. every time we call

.toJson. This slows down compilation and also produces more objects at runtime, which will impact runtime performance. - unexpected things may be derived.

The first caveat is self evident, but unexpected derivations manifests as subtle bugs. Consider what would happen for

if we forgot to provide an implicit derivation for Option. We might expect a

Foo(Some("hello")) to look like

But it would instead be

because Magnolia derived an Option encoder for us.

This is confusing, we would rather have the compiler tell us if we forgot something. Full auto is therefore not recommended.

8.4 Shapeless

The Shapeless library is notoriously the most complicated library in Scala. The

reason why it has such a reputation is because it takes the implicit language

feature to the extreme: creating a kind of generic programming language at the

level of the types.

This is not an entirely foreign concept: in Scalaz we try to limit our use of

the implicit language feature to typeclasses, but we sometimes ask the

compiler to provide us with evidence relating types. For example Liskov or

Leibniz relationship (<~< and ===), and to Inject a free algebra into a

scalaz.Coproduct of algebras.

To install Shapeless, add the following to build.sbt

At the core of Shapeless are the HList and Coproduct data types

which are generic representations of products and coproducts, respectively.

The sealed trait HNil is for convenience so we never need to type HNil.type.

Shapeless has a clone of the IsoSet datatype, called Generic, which allows

us to move between an ADT and its generic representation:

Many of the data types have a type member (Repr) and an .Aux type alias on

their companion that makes the second type visible. This allows us to request

the Generic[Foo] for a type Foo without having to provide the verbose type

of the generic representation, instead generated by a .materialize macro:

There is a complementary LabelledGeneric that includes the field names

Note that the value of a LabelledGeneric representation is the same as the

Generic representation: field names only exist in the type and are erased at

runtime.

We never need to type KeyTag manually, we use the type alias:

If we want to access the field name from a FieldType[K, A], we ask for

implicit evidence Witness.Aux[K], which allows us to access the value of K

at runtime.

Superficially, this is all we need to know about Shapeless to be able to derive a typeclass. However, things get increasingly complex, so we will proceed with increasingly complex examples.

8.4.1 Example: Equal

A typical pattern to follow is to extend the typeclass that we wish to derive, and put the Shapeless code on its companion. This gives us an implicit scope that the compiler can search with without requiring the user to provide complex imports

The entry point to a Shapeless derivation is a method, gen, requiring two type

parameters: the A that we are deriving and the R for its generic

representation. We then ask for the Generic.Aux[A, R], relating A to R,

and an instance of the Derived typeclass for the R. We begin with this

signature and simple implementation:

We’ve reduced the problem to providing an implicit Equal[R] for an arbitrary

R that has an instance of a Generic. Let’s first consider products, where R

<: HList. This is the signature we want to implement:

because if we can implement it for a head and a tail, the compiler will be able

to recurse on this method until it reaches the end of the list. Where we will

need to provide an instance for the empty HNil

Let’s look to implement these methods

and for coproducts we want to implement these signatures

There is no instance for cnil so it can just throw an exception as it will

never be called: it’s a leak in the type system

For the coproduct case we can only compare two things if they align, which is

when they are both Inl or Inr

It is noteworthy that our methods align with the concept of conquer (hnil),

divide2 (hlist) and alt2 (coproduct)! However, we don’t get any of the

advantages of implementing Decidable, as now we must start from scratch when

writing tests for this code.

So let’s test this thing with a simple ADT

We need to provide instances on the companions:

But it doesn’t compile

Welcome to Shapeless compilation errors!

The problem, which is not at all evident in the error, is that the compiler is unable to work out what R is, and gets caught thinking it is something else. We need to provide the explicit type parameters when calling gen, e.g.

or we can use the Generic macro to help us and let the compiler infer the generic representation

The reason why this fixes the problem is because the type signature

desugars into

The Scala compiler solves type constraints left to right, so it finds many

different solutions to DerivedEqual[R] before constraining it with the

Generic.Aux[A, R]. Another way to solve this is to not use context bounds.

With this in mind, we no longer need the implicit val generic or the explicit

type parameters on the call to .gen. We can wire up @deriving by adding an

entry in deriving.conf (assuming we want to override the scalaz-deriving

implementation)

and write

But replacing the scalaz-deriving version means that compile times get slower.

This is because the compiler is solving N implicit searches for each product

of N fields or coproduct of N products, whereas scalaz-deriving and

Magnolia do not.

Note that when using scalaz-deriving or Magnolia we can put the @deriving on

just the top member of an ADT, but for Shapeless we must add it to all entries.

However, this implementation still has a bug: it fails for recursive types at runtime, e.g.

The reason why this happens is because Equal[Tree] depends on the

Equal[Branch], which depends on the Equal[Tree]. Recursion and BANG!

It must be loaded lazily, not eagerly.

Both scalaz-deriving and Magnolia deal with lazy automatically, but in

Shapeless it is the responsibility of the typeclass author.

The macro types Cached, Strict and Lazy modify the compiler’s type

inference behaviour allowing us to achieve the laziness we require. The pattern

to follow is to use Cached[Strict[_]] on the entry point and Lazy[_] around

the H instances.

It is best to depart from context bounds and SAM types entirely at this point:

While we were at it, we optimised using the quick shortcut from

scalaz-deriving.

We can now call

without a runtime exception.

8.4.2 Example: Default

There are no new snares in the implementation of a typeclass with a type

parameter in covariant position. Here we create HList and Coproduct values,

and must provide a value for the CNil case as it corresponds to the case where

no coproduct is able to provide a value.

Much as we could draw an analogy between Equal and Decidable, we can see the

relationship to Alt in .point (hnil), .apply2 (.hcons) and .altly2

(.ccons).

There is little to be learned from an example like Semigroup, so we will skip

to encoders and decoders.

8.4.3 Example: JsEncoder

To be able to reproduce our Magnolia JSON encoder, we must be able to access:

- field names and class names

- annotations for user preferences

- default values on a

case class

We’ll begin by creating an encoder that handles only the sensible defaults.

To get field names, we use LabelledGeneric instead of Generic, and when

defining the type of the head element, use FieldType[K, H] instead of just

H. Request a Witness.Aux[K] to be able to access the value of the

field name K at runtime.

Shapeless selects codepaths at compiletime based on the presence of annotations, which can lead to more optimised code, at the expense of code repetition. This means that the number of annotations we are dealing with, and their subtypes, must minimised or we can find ourselves writing 10x the amount of code. Let’s refactor our three annotations into one containing all the customisation parameters:

All users of the annotation must provide all three values since default values and convenience methods are not available to annotation constructors. We can write custom extractors so we don’t have to change our Magnolia code

We can request Annotation[json, A] for a case class or sealed trait to get access to the annotation, but we must write an hcons and a ccons dealing with both cases because the evidence will not be generated if the annotation is not present. We therefore have to introduce a lower priority implicit scope and put the “no annotation” evidence there.

We can also request Annotations.Aux[json, A, J] evidence to obtain an HList

of the json annotation for type A. Again, we must provide hcons and

ccons dealing with the case where there is and is not an annotation.

To support this one annotation, we must write four times as much code as before!

Lets start by rewriting the JsEncoder, only handling user code that doesn’t

have any annotations. Now any code that uses the @json will fail to compile,

which is a good safety net.

We must add an A and J type to the DerivedJsEncoder and thread through the

annotations on its .toJsObject method. Our .hcons and .ccons evidence now

provides instances for DerivedJsEncoder with a None.type annotation and we

move them to a lower priority so that we can deal with Annotation[json, A] in

the higher priority.

Note that the evidence for J is listed before R. This is important, since

the compiler must first fix the type of J before it can solve for R.

Now we can add the type signatures for the six new methods, covering all the possibilities of where the annotation can be. Note that we only support one annotation in each position. If the user provides multiple annotations, anything after the first will be silently ignored.

We’re now running out of names for things, so we will arbitrarily call it

Annotated when there is an annotation on the A, and Custom when there is

an annotation on a field:

We don’t actually need .hconsAnnotated or .hconsAnnotatedCustom for

anything, since an annotation on a case class does not mean anything to the

encoding of that product, it is only used in .cconsAnnotated*. We can therefore

delete two methods.

.cconsAnnotated and .cconsAnnotatedCustom can be defined as

and

The use of .head and .get may be concerned but recall that the types here

are :: and Some meaning that these methods are total and safe to use.

.hconsCustom and .cconsCustom are written

and

Obviously, there is a lot of boilerplate, but looking closely one can see that each method is implemented as efficiently as possible with the information it has available: codepaths are selected at compiletime rather than runtime.

The performance obsessed may be able to refactor this code so all annotation

information is available in advance, rather than injected via the .toJsFields

method, with another layer of indirection. For absolute performance, we could

also treat each customisation as a separate annotation, but that would multiply

the amount of code we’ve written yet again, with additional cost to compilation

time on downstream users. Such optimisations are beyond the scope of this book,

but they are possible and people do them: the ability to shift work from runtime

to compiletime is one of the most appealing things about generic programming.

One more caveat that we need to be aware of: LabelledGeneric is not compatible

with scalaz.@@, but there is a workaround. Say we want to effectively ignore

tags so we add the following derivation rules to the companions of our encoder

and decoder

We would then expect to be able to derive a JsDecoder for something like our

TradeTemplate from Chapter 5

But we instead get a compiler error

The error message is as helpful as always. The workaround is to introduce evidence for H @@ Z on the lower priority implicit scope, and then just call the code that the compiler should have found in the first place:

Thankfully, we only need to consider products, since coproducts cannot be tagged.

8.4.4 JsDecoder

The decoding side is much as we can expect based on previous examples. We can

construct an instance of a FieldType[K, H] with the helper field[K](h: H).

Supporting only the sensible defaults means we write:

Adding user preferences via annotations follows the same route as

DerivedJsEncoder and is mechanical, so left as an exercise to the reader.

One final thing is missing: case class default values. We can request evidence

but a big problem is that we can no longer use the same derivation mechanism for

products and coproducts: the evidence is never created for coproducts.

The solution is quite drastic. We must split our DerivedJsDecoder into

DerivedCoproductJsDecoder and DerivedProductJsDecoder. We will focus our

attention on the DerivedProductJsDecoder, and while we are at it we will

use a Map for faster field lookup:

We can request evidence of default values with Default.Aux[A, D] and duplicate

all the methods to deal with the case where we do and do not have a default

value. However, Shapeless is merciful (for once) and provides

Default.AsOptions.Aux[A, D] letting us handle defaults at runtime.

We must move the .hcons and .hnil methods onto the companion of the new

sealed typeclass, which can handle default values

We can’t use @deriving any more for products and coproducts. One possible hack

is to make DerivedCoproductJsDecoder extend from JsDecoder, adding an entry

in the deriving.conf for DerivedCoproductJsDecoder as well as one for

JsDecoder (which points to DerivedProductJsDecoder), but this adds to the

mental burden at the point of use, which is not ideal.

Oh, and don’t forget to add @@ support

8.4.5 Complicated Derivations

Shapeless allows for a lot more kinds of derivations than are possible with

scalaz-deriving or Magnolia. As an example of an encoder / decoder than are

not possible with Magnolia, consider this simple XML model from xmlformat

Given the nature of XML it makes sense to have separate encoder / decoder pairs

for XChildren and XString content. We could provide a derivation for the

XChildren with Shapeless but we want to special case fields based on the kind

of typeclass they have, as well as Option fields. We could even require that

fields are annotated with their encoded name. In addition, when decoding we wish

to have different strategies for handling XML element bodies, which can be

multipart, depending on if our type has a Semigroup, Monoid or neither.

8.4.6 Example: UrlQueryWriter

Along similar lines as xmlformat, our drone-dynamic-agents application could

benefit from a typeclass derivation of the UrlQueryWriter typeclass, which is

built out of UrlEncodedWriter instances for each field entry. It does not

support coproducts:

It is reasonable to ask if these 30 lines are an improvement over the 16 lines for the 3 manual instances our application needs.

8.4.7 The Dark Side of Derivation

“Beware fully automatic derivation. Anger, fear, aggression; the dark side of the derivation are they. Easily they flow, quick to join you in a fight. If once you start down the dark path, forever will it dominate your compiler, consume you it will.”

― an ancient Shapeless master

In addition to all the warnings about fully automatic derivation that were mentioned for Magnolia, Shapeless is much worse. Not only is fully automatic Shapeless derivation the most common cause of slow compiles, it is also a painful source of typeclass coherence bugs.

Fully automatic derivation is when the def gen are implicit such that a call

will recurse for all entries in the ADT. Because of the way that implicit scopes

work, an imported implicit def will have a higher priority than custom

instances on companions, creating a source of typeclass decoherence. For

example, consider this code if our .gen were implicit

We might expect the full-auto encoded form of Bar("hello") to look like

because we have used xderiving for Foo. But it can instead be

Worse yet is when implicit methods are added to the companion of the typeclass, meaning that the typeclass is always derived at the point of use and users are unable opt out.

Fundamentally, when writing generic programs, implicits can be ignored by the compiler depending on scope, meaning that we lose the compiletime safety that was our motivation for programming at the type level in the first place!

Everything is much simpler in the light side, where implicit is only used for

coherent, globally unique, typeclasses. Fear of boilerplate is the path to the

dark side. Fear leads to anger. Anger leads to hate. Hate leads to suffering.

8.5 Performance

There is no silver bullet when it comes to typeclass derivation. An axis to consider is performance: both at compiletime and runtime.

8.5.0.1 Compile Times

When it comes to compilation times, Shapeless is the outlier. It is not uncommon

to see a small project expand from a one second compile to a one minute compile.

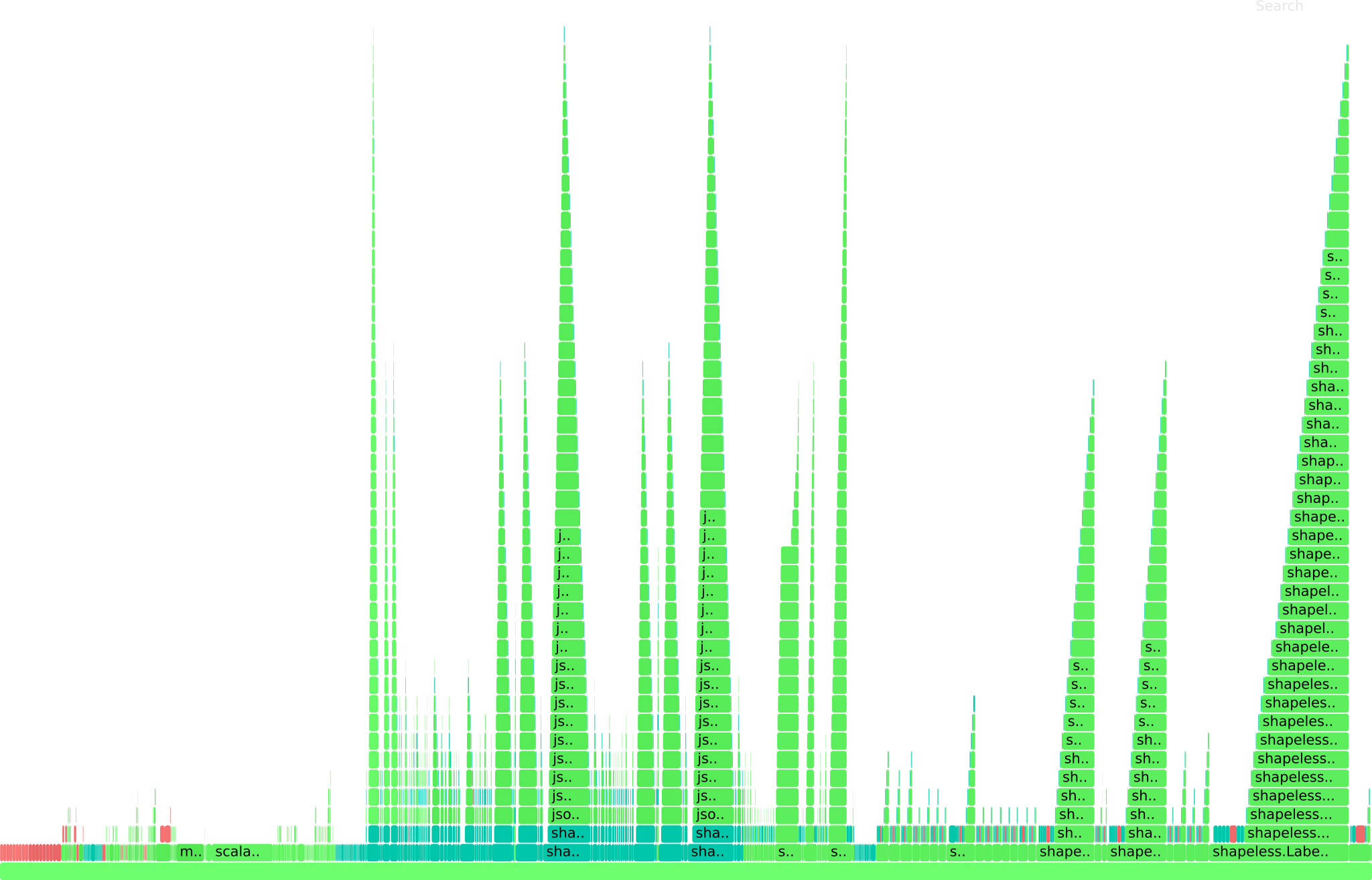

To investigate compilation issues, we can profile our applications with the

scalac-profiling plugin

It produces output that can generate a flame graph.

For a typical Shapeless derivation, we get a lively chart

almost the entire compile time is spent in implicit resolution. Note that this

also includes compiling the scalaz-deriving, Magnolia and manual instances,

but the Shapeless computations dominate. Implicit resolution for

scalaz-deriving, Magnolia and manual instances are simple: everything is on

the data type companions.

And this is when it works. If there is a problem with a shapeless derivation, the compiler can get stuck in an infinite loop and must be killed.

8.5.0.2 Runtime Performance

If we move to runtime performance, the answer is always it depends.

Assuming that the derivation logic has been written in an efficient way, it is only possible to know which is faster through experimentation.

The jsonformat library uses the Java Microbenchmark Harness (JMH) on models

that map to GeoJSON, Google Maps, and Twitter, contributed by Andriy

Plokhotnyuk. There are three tests per model:

- encoding the

ADTto aJsValue - a successful decoding of the same

JsValueback into an ADT - a failure decoding of a

JsValuewith a data error

applied to the following implementations:

- Magnolia

- Shapeless

- manually written

with the equivalent optimisations in each. The results are in operations per second (higher is better), on a powerful desktop computer, using a single thread:

We see that the manual implementations are in the lead, followed by Magnolia, with Shapeless from 30% to 70% the performance of the manual instances. Now for decoding

This is a tighter race, with Shapeless keeping pace with Magnolia, by and large,

and manual instances performing the best on the GeoJSON data. Finally, decoding

from a JsValue that contains invalid data (in an intentionally awkward

position)

Just when we thought we were seeing a pattern, both Magnolia and Shapeless win the race when decoding invalid GeoJSON data, but manual instances win the Google Maps and Twitter challenges.

We want to include scalaz-deriving in the comparison, so we compare an

equivalent implementation of Equal, tested on two values that contain the same

contents (True) and two values that contain slightly different contents

(False)

As expected, the manual instances are far ahead of the crowd, with Shapeless

mostly leading the automatic derivations. scalaz-deriving makes a great effort

for GeoJSON but falls far behind in both the Google Maps and Twitter tests. The

False tests are more of the same:

The runtime performance of scalaz-deriving, Magnolia and Shapeless is usually

good enough. Let’s be honest: we are not writing applications that need to be

able to encode more than 130,000 values to JSON, per second, on a single core,

on the JVM. If that’s a problem, you might want to look into C++.

It is unlikely that derived instances will be an application’s bottleneck. Even if it is, there is the manually written escape hatch, which is more powerful and therefore more dangerous: it is easy to introduce typos, bugs, and even performance regressions by accident when writing a manual instance.

In conclusion: hokey derivations and ancient macros are no match for a good hand written instance at your side, kid.

8.6 Summary

When deciding on a technology to use for typeclass derivation, this feature chart may help:

| Feature | Scalaz | Magnolia | Shapeless | Manual |

|---|---|---|---|---|

@deriving |

yes | yes | yes | |

| Laws | yes | |||

| Fast compiles | yes | yes | yes | |

| Field names | yes | yes | ||

| Annotations | yes | partially | ||

| Default values | yes | with caveats | ||

| Complicated | painfully so | |||

| Performance | hold my beer |

Prefer scalaz-deriving if possible, using Magnolia for encoders / decoders or

if performance is a larger concern, escalating to Shapeless for complicated

derivations only if compilation times are not a concern.

Manual instances are always an escape hatch for special cases and to achieve the ultimate performance. Avoid introducing typo bugs with manual instances by using a code generation tool.