5. Scalaz Typeclasses

In this chapter we will tour most of the typeclasses in scalaz-core.

We don’t use everything in drone-dynamic-agents so we will give

standalone examples when appropriate.

There has been criticism of the naming in scalaz, and functional

programming in general. Most names follow the conventions introduced

in the Haskell programming language, based on Category Theory. Feel

free to set up type aliases in your own codebase if you would prefer

to use verbs based on the primary functionality of the typeclass (e.g.

Mappable, Pureable, FlatMappable) until you are comfortable with

the standard names.

Before we introduce the typeclass hierarchy, we will peek at the four most important methods from a control flow perspective: the methods we will use the most in typical FP applications:

| Typeclass | Method | From | Given | To |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Functor |

map |

F[A] |

A => B |

F[B] |

Applicative |

pure |

A |

F[A] |

|

Monad |

flatMap |

F[A] |

A => F[B] |

F[B] |

Traverse |

traverse |

F[A] |

A => G[B] |

G[F[B]] |

We know that operations which return a F[_] can be run sequentially

in a for comprehension by .flatMap, defined on its Monad[F]. The

context F[_] can be thought of as a container for an intentional

effect with A as the output: flatMap allows us to generate new

effects F[B] at runtime based on the results of evaluating previous

effects.

Of course, not all type constructors F[_] are effectful, even if

they have a Monad[F]. Often they are data structures. By using the

least specific abstraction, we can reuse code for List, Either,

Future and more.

If we only need to transform the output from an F[_], that’s just

map, introduced by Functor. In Chapter 3, we ran effects in

parallel by creating a product and mapping over them. In Functional

Programming, parallelisable computations are considered less

powerful than sequential ones.

In between Monad and Functor is Applicative, defining pure

that lets us lift a value into an effect, or create a data structure

from a single value.

traverse is useful for rearranging type constructors. If you find

yourself with an F[G[_]] but you really need a G[F[_]] then you

need Traverse. For example, say you have a List[Future[Int]] but

you need it to be a Future[List[Int]], just call

.traverse(identity), or its simpler sibling .sequence.

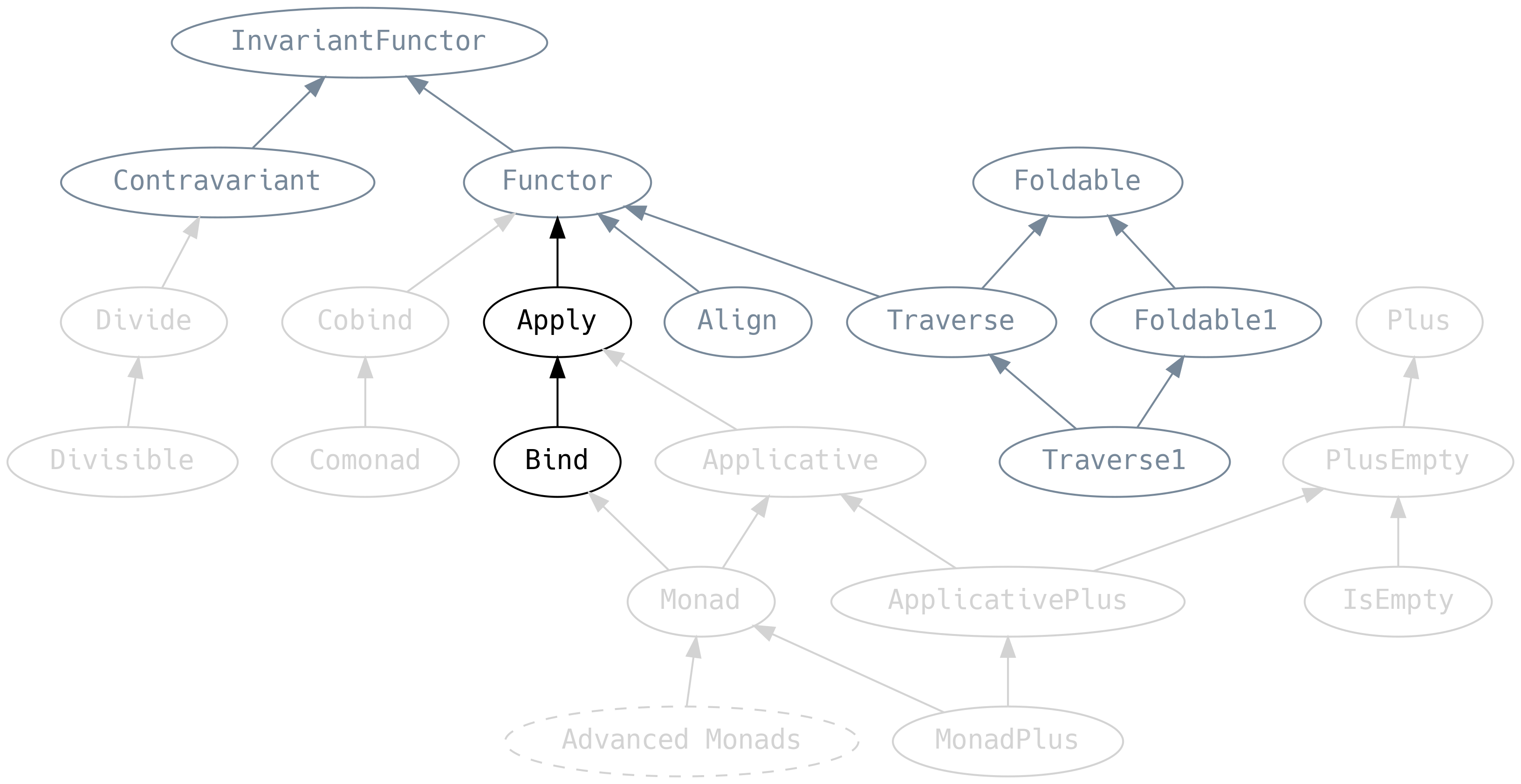

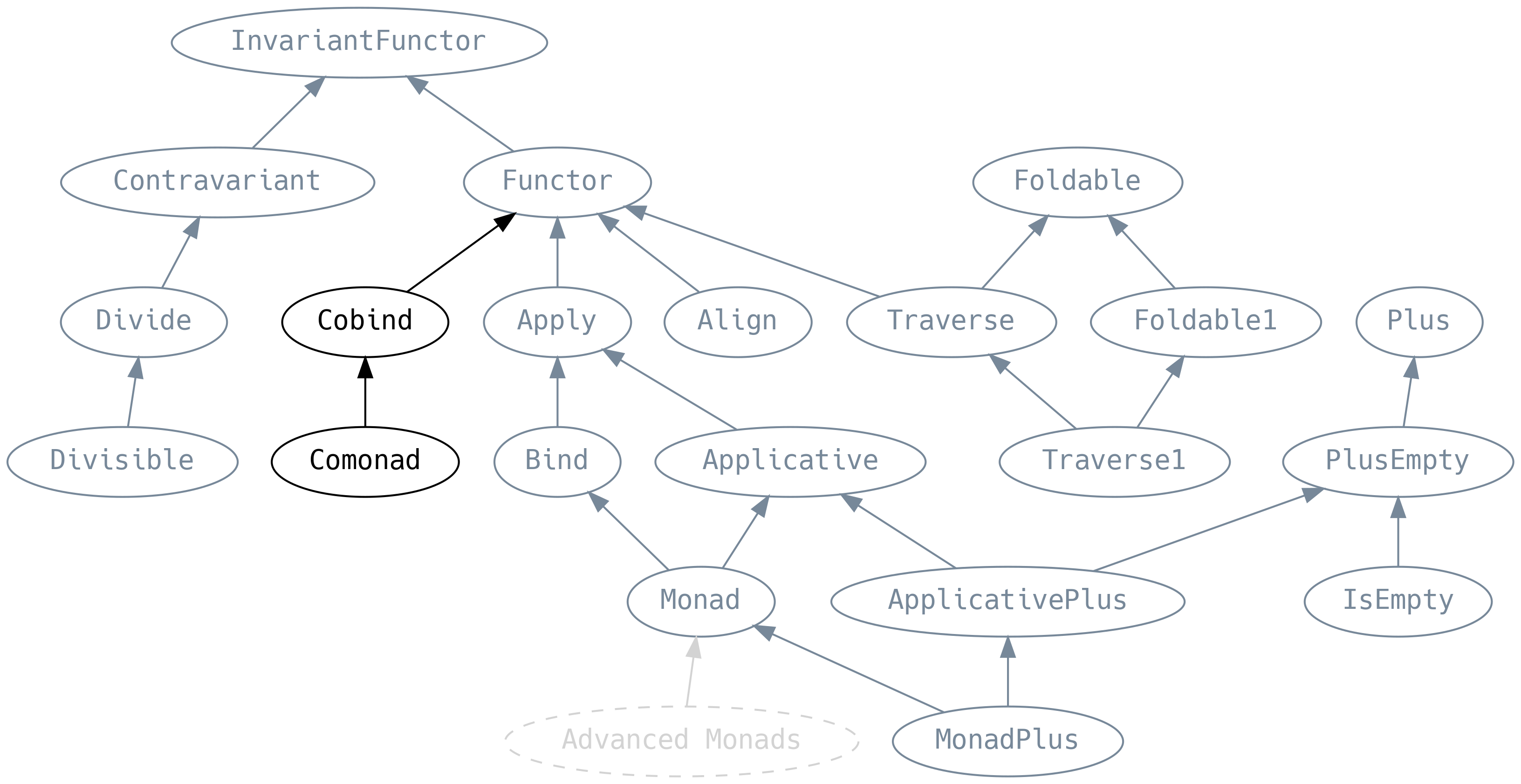

5.1 Agenda

This chapter is longer than usual and jam-packed with information: it is perfectly reasonable to attack it over several sittings. You are not expected to remember everything (doing so would require super-human powers) so treat this chapter as a way of knowing where to look for more information.

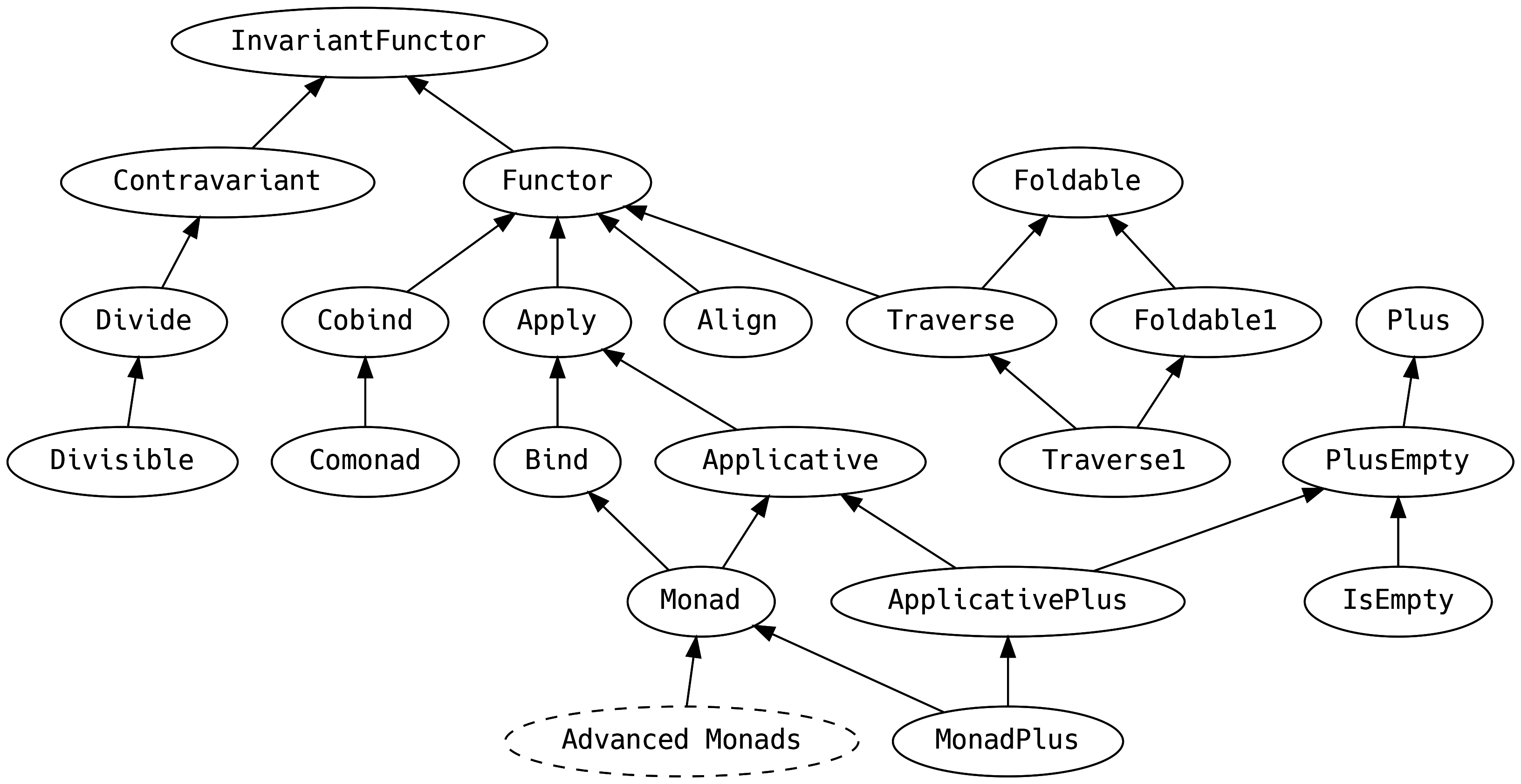

Notably absent are typeclasses that extend Monad, which get their

own chapter later.

Scalaz uses code generation, not simulacrum. However, for brevity, we present

code snippets with @typeclass. Equivalent syntax is available when we import

scalaz._, Scalaz._ and is available under the scalaz.syntax package in the

scalaz source code.

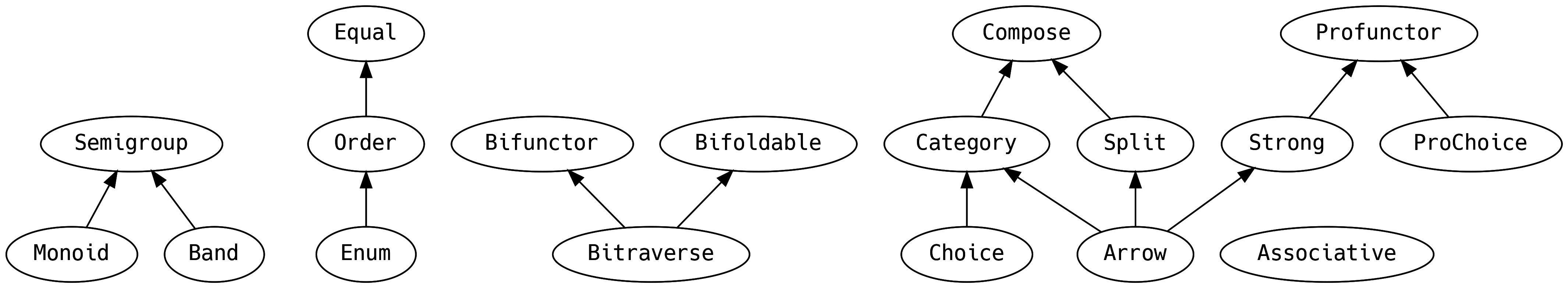

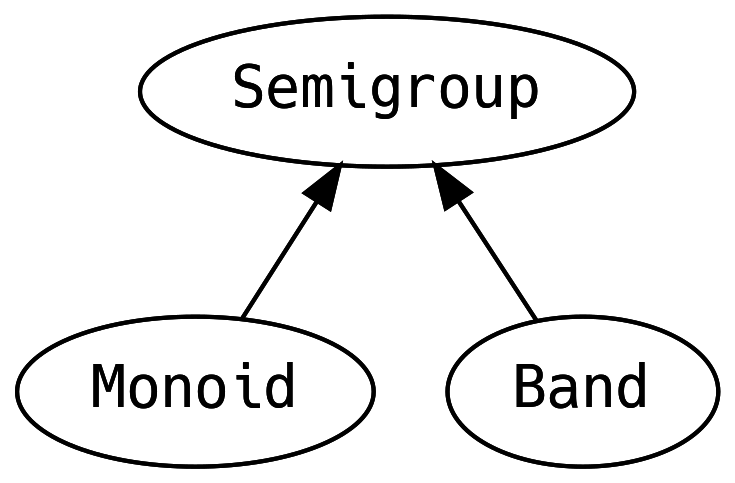

5.2 Appendable Things

A Semigroup should exist for a type if two elements can be combined

to produce another element of the same type. The operation must be

associative, meaning that the order of nested operations should not

matter, i.e.

A Monoid is a Semigroup with a zero element (also called empty

or identity). Combining zero with any other a should give a.

This is probably bringing back memories of Numeric from Chapter 4,

which tried to do too much and was unusable beyond the most basic of

number types. There are implementations of Monoid for all the

primitive numbers, but the concept of appendable things is useful

beyond numbers.

Band has the law that the append operation of the same two

elements is idempotent, i.e. gives the same value. Examples are

anything that can only be one value, such as Unit, least upper

bounds, or a Set. Band provides no further methods yet users can

make use of the guarantees for performance optimisation.

As a realistic example for Monoid, consider a trading system that

has a large database of reusable trade templates. Creating the default

values for a new trade involves selecting and combining templates with

a “last rule wins” merge policy (e.g. if templates have a value for

the same field).

We’ll create a simple template schema to demonstrate the principle, but keep in mind that a realistic system would have a more complicated ADT.

If we write a method that takes templates: List[TradeTemplate], we

only need to call

and our job is done!

But to get zero or call |+| we must have an instance of

Monoid[TradeTemplate]. Although we will generically derive this in a

later chapter, for now we’ll create an instance on the companion:

However, this doesn’t do what we want because Monoid[Option[A]] will append

its contents, e.g.

whereas we want “last rule wins”. We can override the default

Monoid[Option[A]] with our own:

Now everything compiles, let’s try it out…

All we needed to do was implement one piece of business logic and

Monoid took care of everything else for us!

Note that the list of payments are concatenated. This is because the

default Monoid[List] uses concatenation of elements and happens to

be the desired behaviour. If the business requirement was different,

it would be a simple case of providing a custom

Monoid[List[LocalDate]]. Recall from Chapter 4 that with compiletime

polymorphism we can have a different implementation of append

depending on the E in List[E], not just the base runtime class

List.

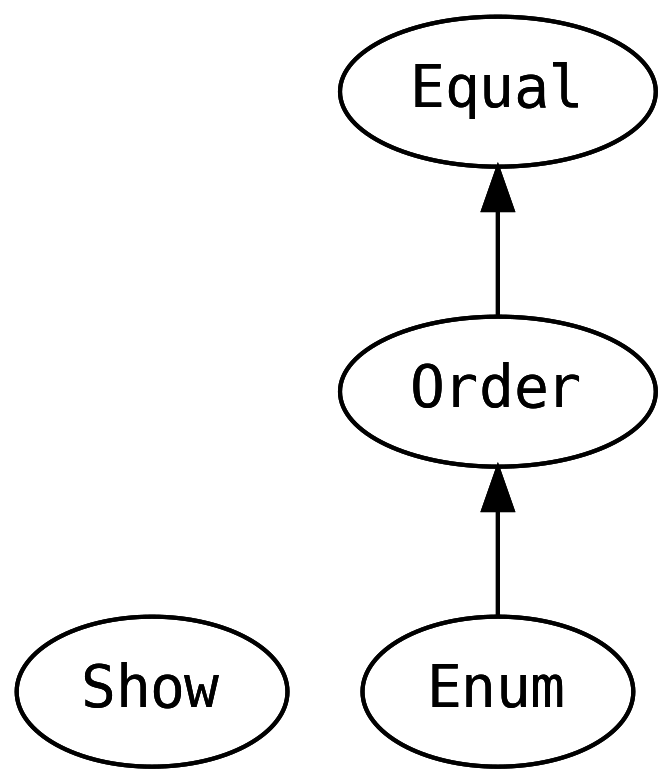

5.3 Objecty Things

In the chapter on Data and Functionality we said that the JVM’s notion

of equality breaks down for many things that we can put into an ADT.

The problem is that the JVM was designed for Java, and equals is

defined on java.lang.Object whether it makes sense or not. There is

no way to remove equals and no way to guarantee that it is

implemented.

However, in FP we prefer typeclasses for polymorphic functionality and even concepts as simple equality are captured at compiletime.

Indeed === (triple equals) is more typesafe than == (double

equals) because it can only be compiled when the types are the same

on both sides of the comparison. You’d be surprised how many bugs this

catches.

equal has the same implementation requirements as Object.equals

-

commutative

f1 === f2impliesf2 === f1 -

reflexive

f === f -

transitive

f1 === f2 && f2 === f3impliesf1 === f3

By throwing away the universal concept of Object.equals we don’t

take equality for granted when we construct an ADT, stopping us at

compiletime from expecting equality when there is none.

Continuing the trend of replacing old Java concepts, rather than data

being a java.lang.Comparable, they now have an Order according

to:

Order implements .equal in terms of the new primitive .order. When a

typeclass implements a parent’s primitive combinator with a derived

combinator, an implied law of substitution for the typeclass is added. If an

instance of Order were to override .equal for performance reasons, it must

behave identically the same as the original.

Things that have an order may also be discrete, allowing us to walk successors and predecessors:

We’ll discuss EphemeralStream in the next chapter, for now you just

need to know that it is a potentially infinite data structure that

avoids memory retention problems in the stdlib Stream.

Similarly to Object.equals, the concept of a .toString on every

class does not make sense in Java. We would like to enforce

stringyness at compiletime and this is exactly what Show achieves:

We’ll explore Cord in more detail in the chapter on data types, you

need only know that it is an efficient data structure for storing and

manipulating String.

Unfortunately, due to Scala’s default implicit conversions in

Predef, and language level support for toString in interpolated

strings, it can be incredibly hard to remember to use shows instead

of toString.

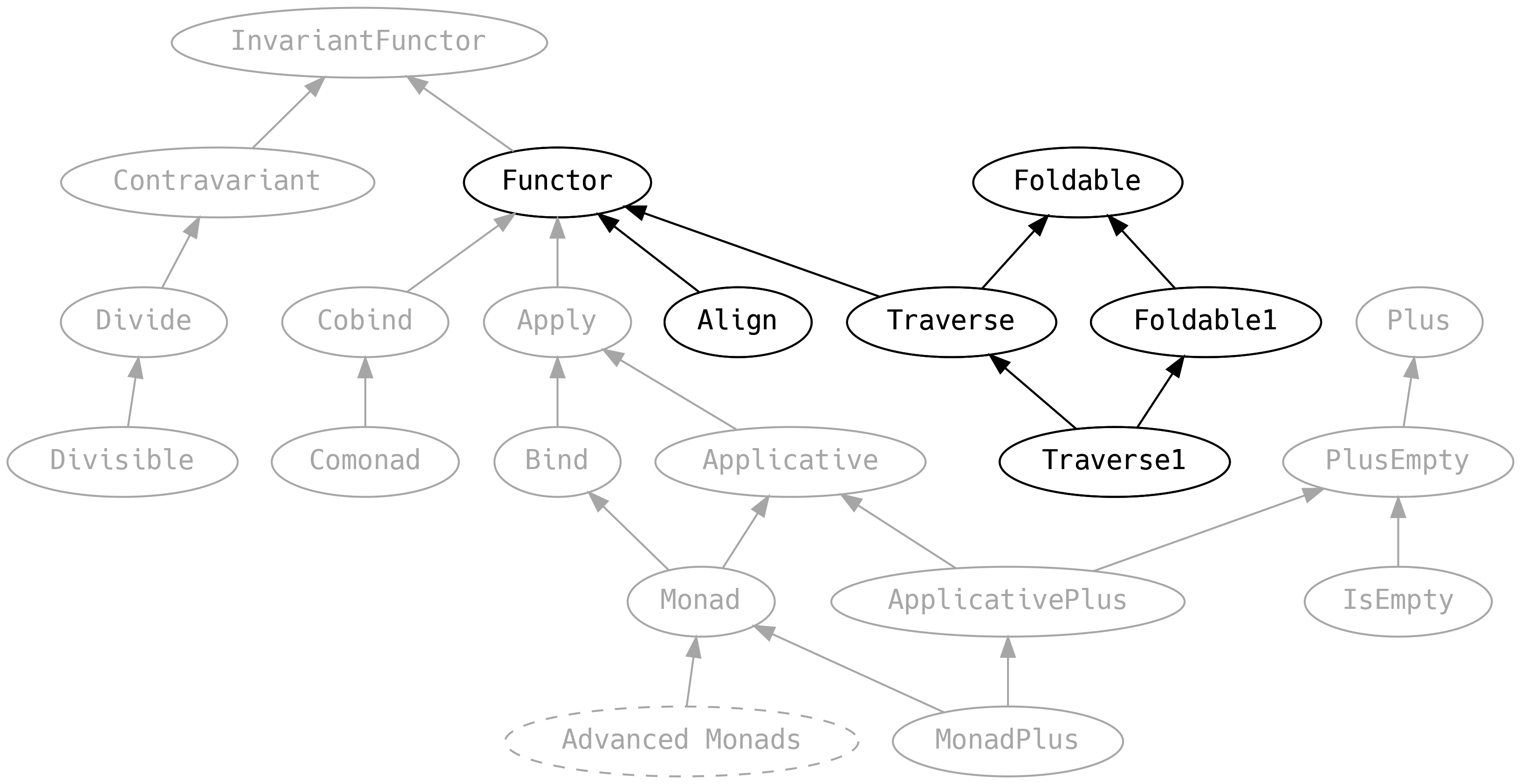

5.4 Mappable Things

We’re focusing on things that can be mapped over, or traversed, in some sense:

5.4.1 Functor

The only abstract method is map, and it must compose, i.e. mapping

with f and then again with g is the same as mapping once with the

composition of f and g:

The map should also perform a no-op if the provided function is

identity (i.e. x => x)

Functor defines some convenience methods around map that can be

optimised by specific instances. The documentation has been

intentionally omitted in the above definitions to encourage you to

guess what a method does before looking at the implementation. Please

spend a moment studying only the type signature of the following

before reading further:

-

voidtakes an instance of theF[A]and always returns anF[Unit], it forgets all the values whilst preserving the structure. -

fproducttakes the same input asmapbut returnsF[(A, B)], i.e. it tuples the contents with the result of applying the function. This is useful when we wish to retain the input. -

fpairtwins all the elements ofAinto a tupleF[(A, A)] -

strengthLpairs the contents of anF[B]with a constantAon the left. -

strengthRpairs the contents of anF[A]with a constantBon the right. -

lifttakes a functionA => Band returns aF[A] => F[B]. In other words, it takes a function over the contents of anF[A]and returns a function that operates on theF[A]directly. -

mapplyis a mind bender. Say you have anF[_]of functionsA => Band a valueA, then you can get anF[B]. It has a similar signature topurebut requires the caller to provide theF[A => B].

fpair, strengthL and strengthR look pretty useless, but they are

useful when we wish to retain some information that would otherwise be

lost to scope.

Functor has some special syntax:

as and >| are a way of replacing the output with a constant.

In our example application, as a nasty hack (which we didn’t even

admit to until now), we defined start and stop to return their

input:

This allowed us to write terse business logic such as

and

But this hack pushes unnecessary complexity into the implementations. It is

better if we let our algebras return F[Unit] and use as:

and

As a bonus, we are now using the less powerful Functor instead of

Monad when starting a node.

5.4.2 Foldable

Technically, Foldable is for data structures that can be walked to

produce a summary value. However, this undersells the fact that it is

a one-typeclass army that can provide most of what you’d expect to see

in a Collections API.

There are so many methods we are going to have to split them out, beginning with the abstract methods:

An instance of Foldable need only implement foldMap and

foldRight to get all of the functionality in this typeclass,

although methods are typically optimised for specific data structures.

You might recognise foldMap by its marketing buzzword name, MapReduce. Given

an F[A], a function from A to B, and a way to combine B (provided by the

Monoid, along with a zero B), we can produce a summary value of type B.

There is no enforced operation order, allowing for parallel computation.

foldRight does not require its parameters to have a Monoid,

meaning that it needs a starting value z and a way to combine each

element of the data structure with the summary value. The order for

traversing the elements is from right to left and therefore it cannot

be parallelised.

foldLeft traverses elements from left to right. foldLeft can be

implemented in terms of foldMap, but most instances choose to

implement it because it is such a basic operation. Since it is usually

implemented with tail recursion, there are no byname parameters.

The only law for Foldable is that foldLeft and foldRight should

each be consistent with foldMap for monoidal operations. e.g.

appending an element to a list for foldLeft and prepending an

element to a list for foldRight. However, foldLeft and foldRight

do not need to be consistent with each other: in fact they often

produce the reverse of each other.

The simplest thing to do with foldMap is to use the identity

function, giving fold (the natural sum of the monoidal elements),

with left/right variants to allow choosing based on performance

criteria:

Recall that when we learnt about Monoid, we wrote this:

We now know this is silly and we should have written:

.fold doesn’t work on stdlib List because it already has a method

called fold that does it is own thing in its own special way.

The strangely named intercalate inserts a specific A between each

element before performing the fold

which is a generalised version of the stdlib’s mkString:

The foldLeft provides the means to obtain any element by traversal

index, including a bunch of other related methods:

Scalaz is a pure library of only total functions, whereas the stdlib .apply

returns A and can throw an exception, Foldable.index returns an Option[A]

with the convenient .indexOr returning an A when a default value is

provided. .element is similar to the stdlib .contains but uses Equal

rather than ill-defined JVM equality.

These methods really sound like a collections API. And, of course,

anything with a Foldable can be converted into a List

There are also conversions to other stdlib and scalaz data types such

as .toSet, .toVector, .toStream, .to[T <: TraversableLike],

.toIList and so on.

There are useful predicate checks

filterLength is a way of counting how many elements are true for a

predicate, all and any return true if all (or any) element meets

the predicate, and may exit early.

We can split an F[A] into parts that result in the same B with

splitBy

for example

noting that there are two parts indexed by f.

splitByRelation avoids the need for an Equal but we must provide

the comparison operator.

splitWith splits the elements into groups that alternatively satisfy

and don’t satisfy the predicate. selectSplit selects groups of

elements that satisfy the predicate, discarding others. This is one of

those rare occasions when two methods share the same type signature

but have different meanings.

findLeft and findRight are for extracting the first element (from

the left, or right, respectively) that matches a predicate.

Making further use of Equal and Order, we have the distinct

methods which return groupings.

distinct is implemented more efficiently than distinctE because it

can make use of ordering and therefore use a quicksort-esque algorithm

that is much faster than the stdlib’s naive List.distinct. Data

structures (such as sets) can implement distinct in their Foldable

without doing any work.

distinctBy allows grouping by the result of applying a function to

the elements. For example, grouping names by their first letter.

We can make further use of Order by extracting the minimum or

maximum element (or both extrema) including variations using the Of

or By pattern to first map to another type or to use a different

type to do the order comparison.

For example we can ask which String is maximum By length, or what

is the maximum length Of the elements.

This concludes the key features of Foldable. You are forgiven for

already forgetting all the methods you’ve just seen: the key takeaway

is that anything you’d expect to find in a collection library is

probably on Foldable and if it isn’t already, it probably should be.

We’ll conclude with some variations of the methods we’ve already seen.

First there are methods that take a Semigroup instead of a Monoid:

returning Option to account for empty data structures (recall that

Semigroup does not have a zero).

The typeclass Foldable1 contains a lot more Semigroup variants of

the Monoid methods shown here (all suffixed 1) and makes sense for

data structures which are never empty, without requiring a Monoid on

the elements.

Very importantly, there are variants that take monadic return values.

We already used foldLeftM when we first wrote the business logic of

our application, now you know that Foldable is where it came from:

You may also see Curried versions, e.g.

5.4.3 Traverse

Traverse is what happens when you cross a Functor with a Foldable

At the beginning of the chapter we showed the importance of traverse

and sequence for swapping around type constructors to fit a

requirement (e.g. List[Future[_]] to Future[List[_]]). You will

use these methods more than you could possibly imagine.

In Foldable we weren’t able to assume that reverse was a universal

concept, but now we can reverse a thing.

We can also zip together two things that have a Traverse, getting

back None when one side runs out of elements, using zipL or zipR

to decide which side to truncate when the lengths don’t match. A

special case of zip is to add an index to every entry with

indexed.

zipWithL and zipWithR allow combining the two sides of a zip

into a new type, and then returning just an F[C].

mapAccumL and mapAccumR are regular map combined with an

accumulator. If you find your old Java sins are making you want to

reach for a var, and refer to it from a map, you want mapAccumL.

For example, let’s say we have a list of words and we want to blank out words we’ve already seen. The filtering algorithm is not allowed to process the list of words a second time so it can be scaled to an infinite stream:

Finally Traverse1, like Foldable1, provides variants of these

methods for data structures that cannot be empty, accepting the weaker

Semigroup instead of a Monoid, and an Apply instead of an

Applicative.

5.4.4 Align

Align is about merging and padding anything with a Functor. Before

looking at Align, meet the \&/ data type (spoken as These, or

hurray!).

i.e. it is a data encoding of inclusive logical OR.

Hopefully by this point you are becoming more capable of reading type signatures to understand the purpose of a method.

alignWith takes a function from either an A or a B (or both) to

a C and returns a lifted function from a tuple of F[A] and F[B]

to an F[C]. align constructs a \&/ out of two F[_].

merge allows us to combine two F[A] when A has a Semigroup. For example,

the implementation of Semigroup[Map[K, V]] defers to Semigroup[V], combining

two entries results in combining their values, having the consequence that

Map[K, List[A]] behaves like a multimap:

and a Map[K, Int] simply tally their contents when merging:

.pad and .padWith are for partially merging two data structures that might

be missing values on one side. For example if we wanted to aggregate independent

votes and retain the knowledge of where the votes came from

There are convenient variants of align that make use of the

structure of \&/

which should make sense from their type signatures. Examples:

Note that the A and B variants use inclusive OR, whereas the

This and That variants are exclusive, returning None if there is

a value in both sides, or no value on either side.

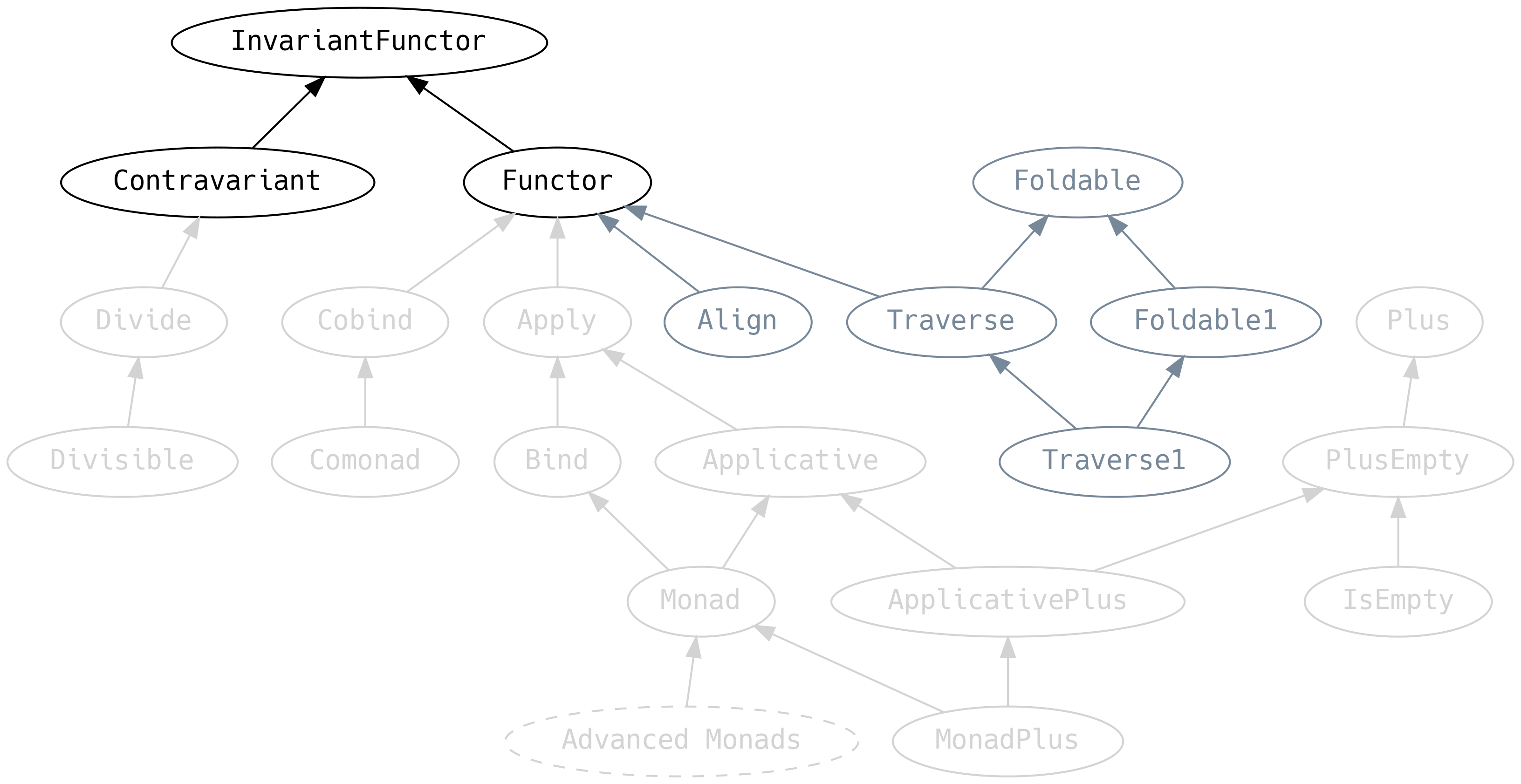

5.5 Variance

We must return to Functor for a moment and discuss an ancestor that

we previously ignored:

InvariantFunctor, also known as the exponential functor, has a

method xmap which says that given a function from A to B, and a

function from B to A, then we can convert F[A] to F[B].

Functor is a short name for what should be covariant functor. But

since Functor is so popular it gets the nickname. Likewise

Contravariant should really be contravariant functor.

Functor implements xmap with map and ignores the function from

B to A. Contravariant, on the other hand, implements xmap with

contramap and ignores the function from A to B:

It is important to note that, although related at a theoretical level,

the words covariant, contravariant and invariant do not directly

refer to Scala type variance (i.e. + and - prefixes that may be

written in type signatures). Invariance here means that it is

possible to map the contents of a structure F[A] into F[B]. Using

identity we can see that A can be safely downcast (or upcast) into

B depending on the variance of the functor.

This sounds so hopelessly abstract that it needs a practical example

immediately, before we can take it seriously. In Chapter 4 we used jsonformat

to derive a JSON encoder for our data types and we gave a brief description of

the JsEncoder typeclass. This is an expanded version:

Now consider the case where we want to write an instance of an JsEncoder[B] in

terms of another JsEncoder[A]: we have a data type Alpha that simply wraps a

Double. This is exactly what contramap is for:

On the other hand, a JsDecoder has a Functor:

Methods on a typeclass can have their type parameters in contravariant position (method parameters) or in covariant position (return type). If a typeclass has a combination of covariant and contravariant positions, it might have an invariant functor.

5.5.1 Composition

Invariants can be composed via methods with intimidating type

signatures. There are many permutations of compose on most

typeclasses, we will not list them all.

The α => type syntax is a kind-projector type lambda that says if

Functor[F] is composed with a type G[_] (that has a Functor[G]), we get a

Functor[F[G[_]]] that operates on the A in F[G[A]].

An example of Functor.compose is where F[_] is List, G[_] is

Option, and we want to be able to map over the Int inside a

List[Option[Int]] without changing the two structures:

This lets us jump into nested effects and structures and apply a function at the layer we want.

5.6 Apply and Bind

Consider this the warm-up act to Applicative and Monad

5.6.1 Apply

Apply extends Functor by adding a method named ap which is

similar to map in that it applies a function to values. However,

with ap, the function is in a similar context to the values.

It is worth taking a moment to consider what that means for a simple data

structure like Option[A], having the following implementation of .ap

To implement .ap, we must first extract the function ff: A => B from f:

Option[A => B], then we can map over fa. The extraction of the function from

the context is the important power that Apply brings, allowing multiple

function to be combined inside the context.

Returning to Apply, we find .applyX boilerplate that allows us to combine

parallel functions and then map over their combined output:

Read .apply2 as a contract promising: “if you give me an F of A and an F

of B, with a way of combining A and B into a C, then I can give you an

F of C”. There are many uses for this contract and the two most important are:

- constructing some typeclasses for a product type

Cfrom its constituentsAandB - performing effects in parallel, like the drone and google algebras we created in Chapter 3, and then combining their results.

Indeed, Apply is so useful that it has special syntax:

which is exactly what we used in Chapter 3:

The syntax <* and *> (left bird and right bird) offer a convenient way to

ignore the output from one of two parallel effects.

Unfortunately, although the |@| syntax is clear, there is a problem

in that a new ApplicativeBuilder object is allocated for each

additional effect. If the work is I/O-bound, the memory allocation

cost is insignificant. However, when performing CPU-bound work, use

the alternative lifting with arity syntax, which does not produce

any intermediate objects:

used like

or directly call applyX

Despite being of most value for dealing with effects, Apply provides

convenient syntax for dealing with data structures. Consider rewriting

as

If we only want the combined output as a tuple, methods exist to do just that:

There are also the generalised versions of ap for more than two

parameters:

along with lift methods that take normal functions and lift them into the

F[_] context, the generalisation of Functor.lift

and apF, a partially applied syntax for ap

Finally forever

repeating an effect without stopping. The instance of Apply must be

stack safe or we’ll get StackOverflowError.

5.6.2 Bind

Bind introduces bind, synonymous with flatMap, which allows

functions over the result of an effect to return a new effect, or for

functions over the values of a data structure to return new data

structures that are then joined.

The .join may be familiar if you have ever used .flatten in the stdlib, it

takes a nested context and squashes it into one.

Although not necessarily implemented as such, we can think of .bind as being a

Functor.map followed by .join

Derived combinators are introduced for .ap and .apply2 that require

consistency with .bind. We will see later that this law has consequences for

parallelisation strategies.

mproduct is like Functor.fproduct and pairs the function’s input

with its output, inside the F.

ifM is a way to construct a conditional data structure or effect:

ifM and ap are optimised to cache and reuse code branches, compare

to the longer form

which produces a fresh List(0) or List(1, 1) every time the branch

is invoked.

Bind also has some special syntax

>> is when we wish to discard the input to bind and >>! is when

we want to run an effect but discard its output.

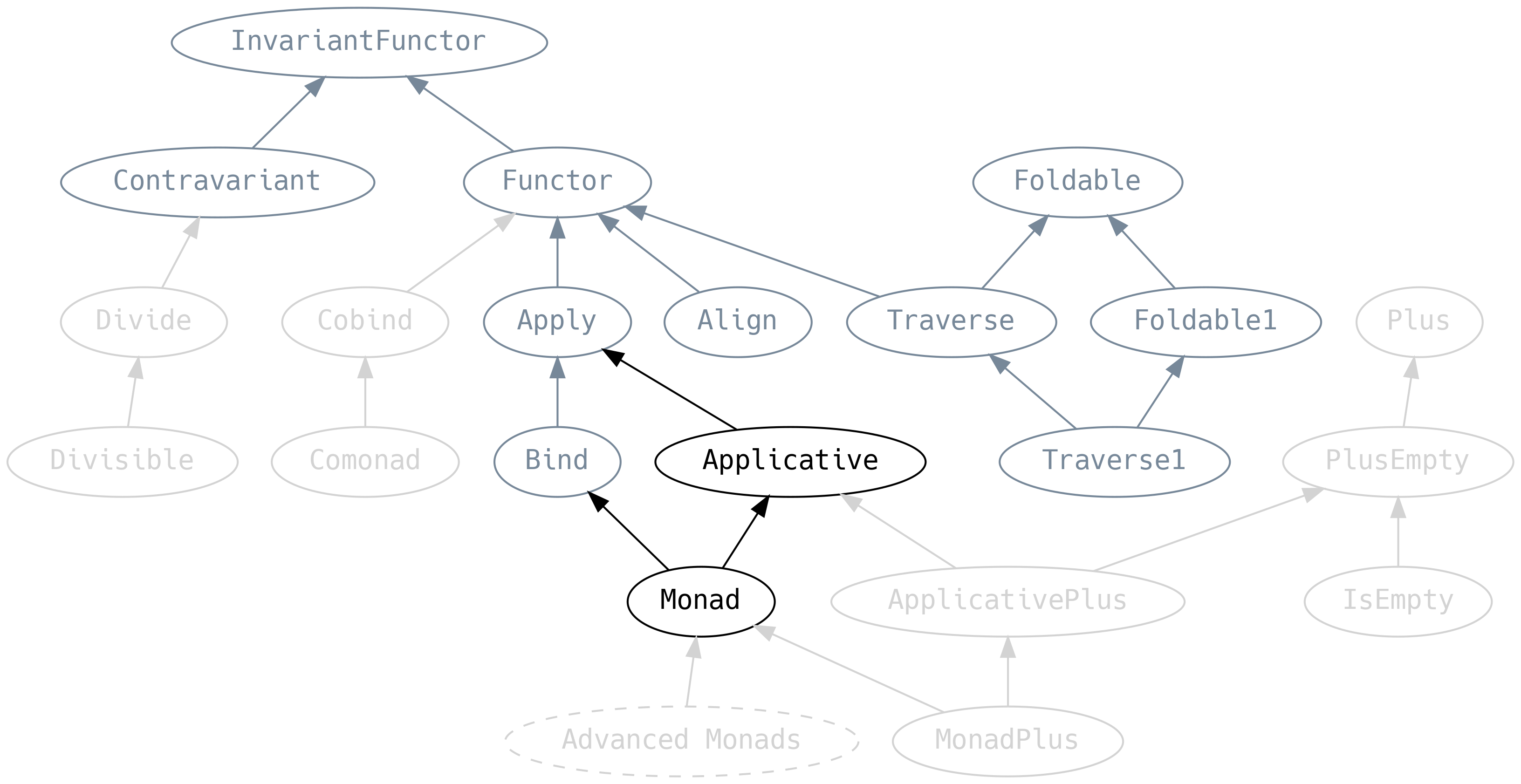

5.7 Applicative and Monad

From a functionality point of view, Applicative is Apply with a

pure method, and Monad extends Applicative with Bind.

In many ways, Applicative and Monad are the culmination of everything we’ve

seen in this chapter. .pure (or .point as it is more commonly known for data

structures) allows us to create effects or data structures from values.

Instances of Applicative must meet some laws, effectively asserting

that all the methods are consistent:

-

Identity:

fa <*> pure(identity) === fa, (wherefais anF[A]) i.e. applyingpure(identity)does nothing. -

Homomorphism:

pure(a) <*> pure(ab) === pure(ab(a))(whereabis anA => B), i.e. applying apurefunction to apurevalue is the same as applying the function to the value and then usingpureon the result. -

Interchange:

pure(a) <*> fab === fab <*> pure(f => f(a)), (wherefabis anF[A => B]), i.e.pureis a left and right identity -

Mappy:

map(fa)(f) === fa <*> pure(f)

Monad adds additional laws:

-

Left Identity:

pure(a).bind(f) === f(a) -

Right Identity:

a.bind(pure(_)) === a -

Associativity:

fa.bind(f).bind(g) === fa.bind(a => f(a).bind(g))wherefais anF[A],fis anA => F[B]andgis aB => F[C].

Associativity says that chained bind calls must agree with nested

bind. However, it does not mean that we can rearrange the order,

which would be commutativity. For example, recalling that flatMap

is an alias to bind, we cannot rearrange

as

start and stop are non-commutative, because the intended

effect of starting then stopping a node is different to stopping then

starting it!

But start is commutative with itself, and stop is commutative with

itself, so we can rewrite

as

which are equivalent. We’re making a lot of assumptions about the Google Container API here, but this is a reasonable choice to make.

A practical consequence is that a Monad must be commutative if its

applyX methods can be allowed to run in parallel. We cheated in

Chapter 3 when we ran these effects in parallel

because we know that they are commutative among themselves. When it comes to interpreting our application, later in the book, we will have to provide evidence that these effects are in fact commutative, or an asynchronous implementation may choose to sequence the operations to be on the safe side.

The subtleties of how we deal with (re)-ordering of effects, and what those effects are, deserves a dedicated chapter on Advanced Monads.

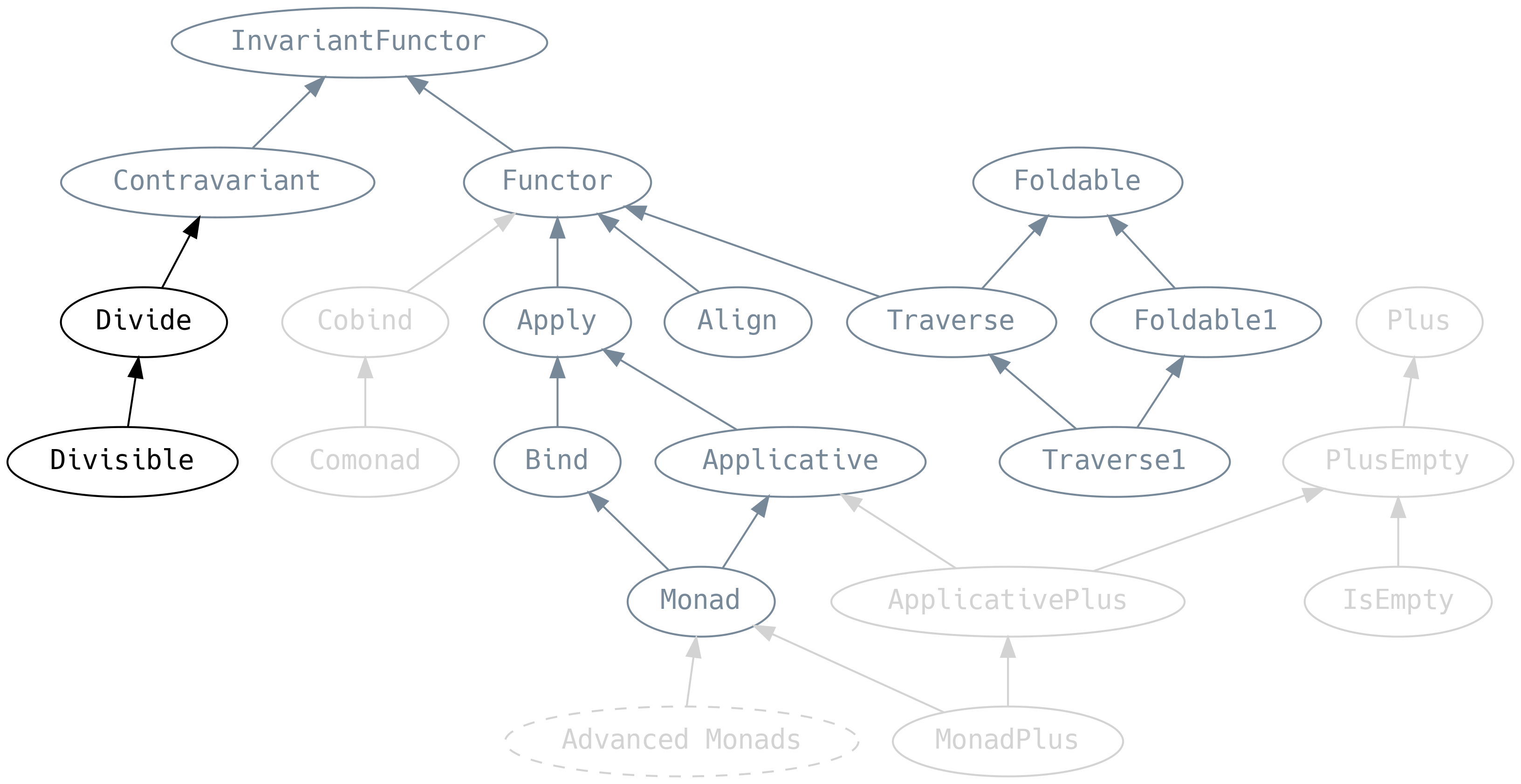

5.8 Divide and Conquer

Divide is the Contravariant analogue of Apply

divide says that if we can break a C into an A and a B, and

we’re given an F[A] and an F[B], then we can get an F[C]. Hence,

divide and conquer.

This is a great way to generate contravariant typeclass instances for

product types by breaking the products into their parts. Scalaz has an

instance of Divide[Equal], let’s construct an Equal for a new

product type Foo

It is a good moment to look again at Apply

It is now easier to spot that applyX is how we can derive typeclasses

for covariant typeclasses.

Mirroring Apply, Divide also has terse syntax for tuples. A softer

divide so that you may reign approach to world domination:

and deriving, which is even more convenient to use for typeclass

derivation:

Generally, if encoder typeclasses can provide an instance of Divide,

rather than stopping at Contravariant, it makes it possible to

derive instances for any case class. Similarly, decoder typeclasses

can provide an Apply instance. We will explore this in a dedicated

chapter on Typeclass Derivation.

Divisible is the Contravariant analogue of Applicative and

introduces conquer, the equivalent of pure

conquer allows creating fallback implementations that effectively ignore the

type parameter. Such values are called universally quantified. For example,

the Divisible[Equal].conquer[String] returns a trivial implementation of

Equal that always returns true, which allows us to implement contramap in

terms of divide

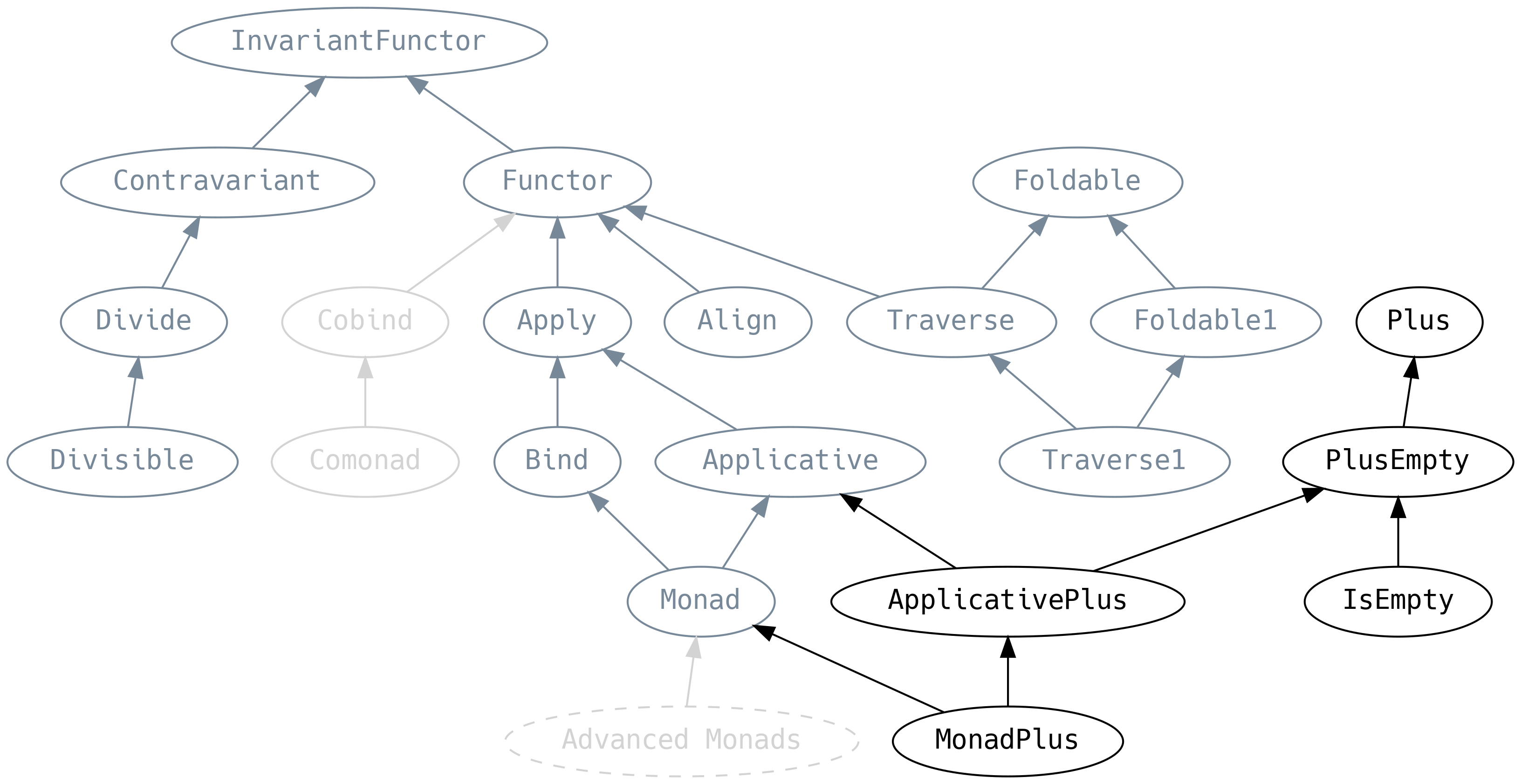

5.9 Plus

Plus is Semigroup but for type constructors, and PlusEmpty is

the equivalent of Monoid (they even have the same laws) whereas

IsEmpty is novel and allows us to query if an F[A] is empty:

Although it may look on the surface as if <+> behaves like |+|

it is best to think of it as operating only at the F[_] level, never looking

into the contents. Plus has the convention that it should ignore failures and

“pick the first winner”. <+> can therefore be used as a mechanism for early

exit (losing information) and failure-handling via fallbacks:

For example, if we have a NonEmptyList[Option[Int]] and we want to ignore

None values (failures) and pick the first winner (Some), we can call <+>

from Foldable1.foldRight1:

In fact, now that we know about Plus, we release that we didn’t need to break

typeclass coherence (when we defined a locally scoped Monoid[Option[A]]) in

the section on Appendable Things. Our objective was to “pick the last winner”,

which is the same as “pick the winner” if the arguments are swapped. Note the

use of the TIE Interceptor for ccy and otc and that b comes before a in

Applicative and Monad have specialised versions of PlusEmpty

ApplicativePlus is also known as Alternative.

unite looks a Foldable.fold on the contents of F[_] but is

folding with the PlusEmpty[F].monoid (not the Monoid[A]). For

example, uniting List[Either[_, _]] means Left becomes empty

(Nil) and the contents of Right become single element List,

which are then concatenated:

withFilter allows us to make use of for comprehension language

support as discussed in Chapter 2. It is fair to say that the Scala

language has built-in language support for MonadPlus, not just

Monad!

Returning to Foldable for a moment, we can reveal some methods that

we did not discuss earlier

msuml does a fold using the Monoid from the PlusEmpty[G] and

collapse does a foldRight using the PlusEmpty of the target

type:

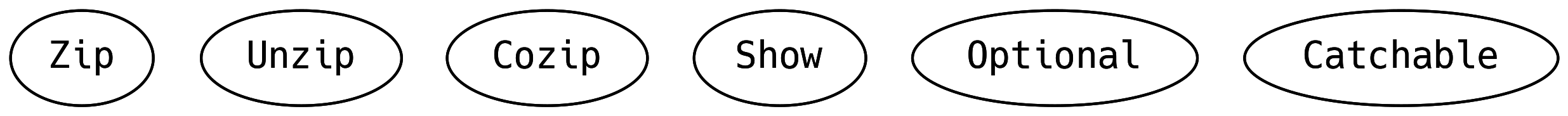

5.10 Lone Wolves

Some of the typeclasses in scalaz are stand-alone and not part of the larger hierarchy.

5.10.1 Zippy

The core method is zip which is a less powerful version of

Divide.tuple2, and if a Functor[F] is provided then zipWith can

behave like Apply.apply2. Indeed, an Apply[F] can be created from

a Zip[F] and a Functor[F] by calling ap.

apzip takes an F[A] and a lifted function from F[A] => F[B],

producing an F[(A, B)] similar to Functor.fproduct.

The core method is unzip with firsts and seconds allowing for

selecting either the first or second element of a tuple in the F.

Importantly, unzip is the opposite of zip.

The methods unzip3 to unzip7 are repeated applications of unzip

to save on boilerplate. For example, if handed a bunch of nested

tuples, the Unzip[Id] is a handy way to flatten them:

In a nutshell, Zip and Unzip are less powerful versions of

Divide and Apply, providing useful features without requiring the

F to make too many promises.

5.10.2 Optional

Optional is a generalisation of data structures that can optionally

contain a value, like Option and Either.

Recall that \/ (disjunction) is scalaz’s improvement of

scala.Either. We will also see Maybe, scalaz’s improvement of

scala.Option

These are methods that should be familiar, except perhaps pextract,

which is a way of letting the F[_] return some implementation

specific F[B] or the value. For example, Optional[Option].pextract

returns Option[Nothing] \/ A, i.e. None \/ A.

Scalaz gives a ternary operator to things that have an Optional

for example

Next time you write a function that takes an Option, consider

rewriting it to take Optional instead: it’ll make it easier to

migrate to data structures that have better error handling without any

loss of functionality.

5.10.3 Catchable

Our grand plans to write total functions that return a value for every input may be in ruins when exceptions are the norm in the Java standard library, the Scala standard library, and the myriad of legacy systems that we must interact with.

scalaz does not magically handle exceptions automatically, but it does provide the mechanism to protect against bad legacy systems.

attempt will catch any exceptions inside F[_] and make the JVM

Throwable an explicit return type that can be mapped into an error

reporting ADT, or left as an indicator to downstream callers that

Here be Dragons.

fail permits callers to throw an exception in the F[_] context

and, since this breaks purity, will be removed from scalaz. Exceptions

that are raised via fail must be later handled by attempt since it

is just as bad as calling legacy code that throws an exception.

It is worth noting that Catchable[Id] cannot be implemented. An

Id[A] cannot exist in a state that may contain an exception.

However, there are instances for both scala.concurrent.Future

(asynchronous) and scala.Either (synchronous), allowing Catchable

to abstract over the unhappy path. MonadError, as we will see in a

later chapter, is a superior replacement.

5.11 Co-things

A co-thing typically has some opposite type signature to whatever thing does, but is not necessarily its inverse. To highlight the relationship between thing and co-thing, we will include the type signature of thing wherever we can.

5.11.1 Cobind

cobind (also known as coflatmap) takes an F[A] => B that acts on

an F[A] rather than its elements. But this is not necessarily the

full fa, it is usually some substructure as defined by cojoin

(also known as coflatten) which expands a data structure.

Compelling use-cases for Cobind are rare, although when shown in the

Functor permutation table (for F[_], A and B) it is difficult

to argue why any method should be less important than the others:

| method | parameter |

|---|---|

map |

A => B |

contramap |

B => A |

xmap |

(A => B, B => A) |

ap |

F[A => B] |

bind |

A => F[B] |

cobind |

F[A] => B |

5.11.2 Comonad

copoint (also copure) unwraps an element from a context. When

interpreting a pure program, we typically require a Comonad to run

the interpreter inside the application’s def main entry point. For

example, Comonad[Future].copoint will await the execution of a

Future[Unit].

Far more interesting is the Comonad of a data structure. This is a

way to construct a view of all elements alongside their neighbours.

Consider a neighbourhood (Hood for short) for a list containing

all the elements to the left of an element (lefts), the element

itself (the focus), and all the elements to its right (rights).

The lefts and rights should each be ordered with the nearest to

the focus at the head, such that we can recover the original IList

via .toList

We can write methods that let us move the focus one to the left

(previous) and one to the right (next)

By introducing more to repeatedly apply an optional function to

Hood we can calculate all the positions that Hood can take in

the list

We can now implement Comonad[Hood]

cojoin gives us a Hood[Hood[IList]] containing all the possible

neighbourhoods in our initial IList

Indeed, cojoin is just positions! We can override it with a more

direct (and performant) implementation

Comonad generalises the concept of Hood to arbitrary data

structures. Hood is an example of a zipper (unrelated to Zip).

Scalaz comes with a Zipper data type for streams (i.e. infinite 1D

data structures), which we will discuss in the next chapter.

One application of a zipper is for cellular automata, which compute the value of each cell in the next generation by performing a computation based on the neighbourhood of that cell.

5.11.3 Cozip

Although named cozip, it is perhaps more appropriate to talk about

its symmetry with unzip. Whereas unzip splits F[_] of tuples

(products) into tuples of F[_], cozip splits F[_] of

disjunctions (coproducts) into disjunctions of F[_].

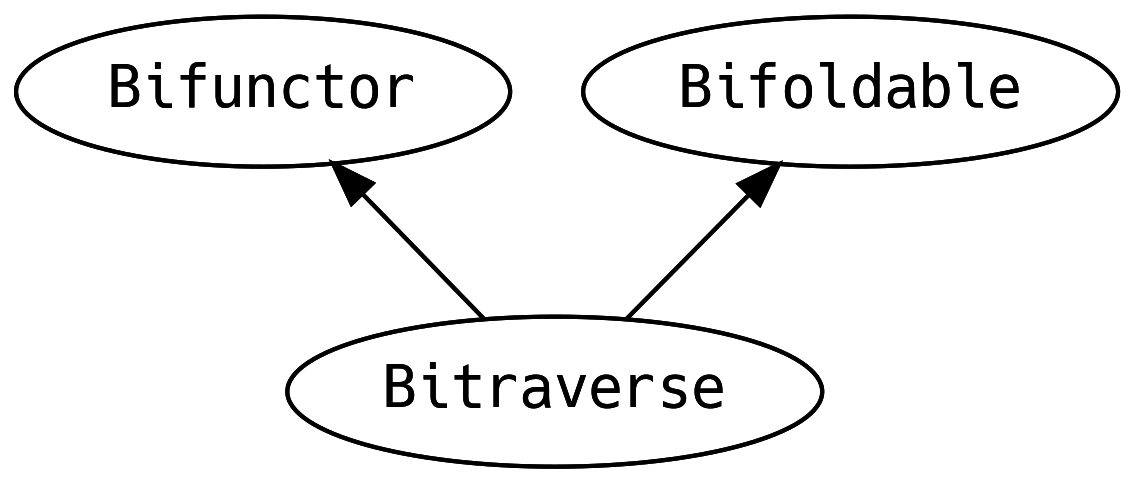

5.12 Bi-things

Sometimes we may find ourselves with a thing that has two type holes

and we want to map over both sides. For example we might be tracking

failures in the left of an Either and we want to do something with the

failure messages.

The Functor / Foldable / Traverse typeclasses have bizarro

relatives that allow us to map both ways.

Although the type signatures are verbose, these are nothing more than

the core methods of Functor, Foldable and Bitraverse taking two

functions instead of one, often requiring both functions to return the

same type so that their results can be combined with a Monoid or

Semigroup.

In addition, we can revisit MonadPlus (recall it is Monad with the

ability to filterWith and unite) and see that it can separate

Bifoldable contents of a Monad

This is very useful if we have a collection of bi-things and we want

to reorganise them into a collection of A and a collection of B

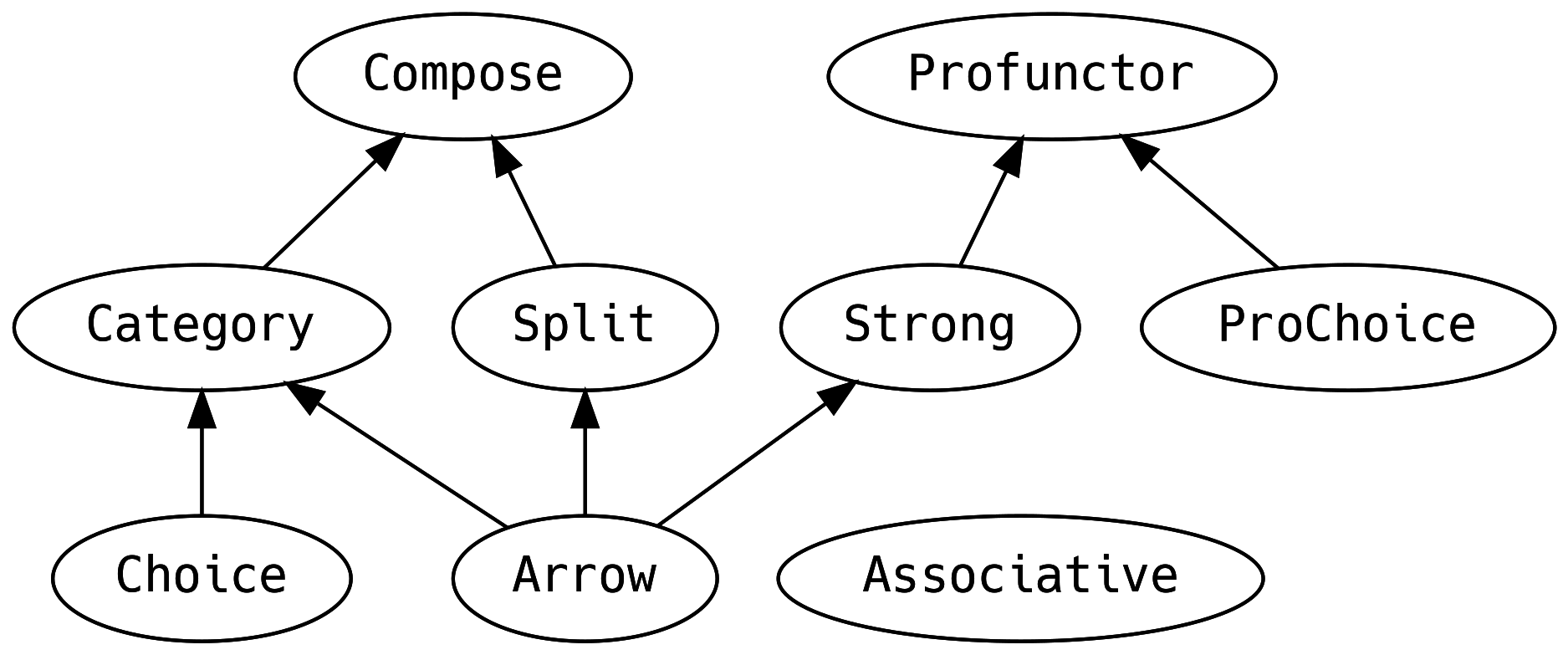

5.13 Very Abstract Things

What remains of the typeclass hierarchy are things that allow us to meta-reason about functional programming and scalaz. We are not going to discuss these yet as they deserve a full chapter on Category Theory and are not needed in typical FP applications.

5.14 Summary

That was a lot of material! We have just explored a standard library of polymorphic functionality. But to put it into perspective: there are more traits in the Scala stdlib Collections API than typeclasses in scalaz.

It is normal for an FP application to only touch a small percentage of the typeclass hierarchy, with most functionality coming from domain-specific typeclasses. Even if the domain-specific typeclasses are just specialised clones of something in scalaz, it is better to write the code and later refactor it, than to over-abstract too early.

To help, we have included a cheat-sheet of the typeclasses and their primary methods in the Appendix, inspired by Adam Rosien’s Scalaz Cheatsheet. These cheat-sheets make an excellent replacement for the family portrait on your office desk.

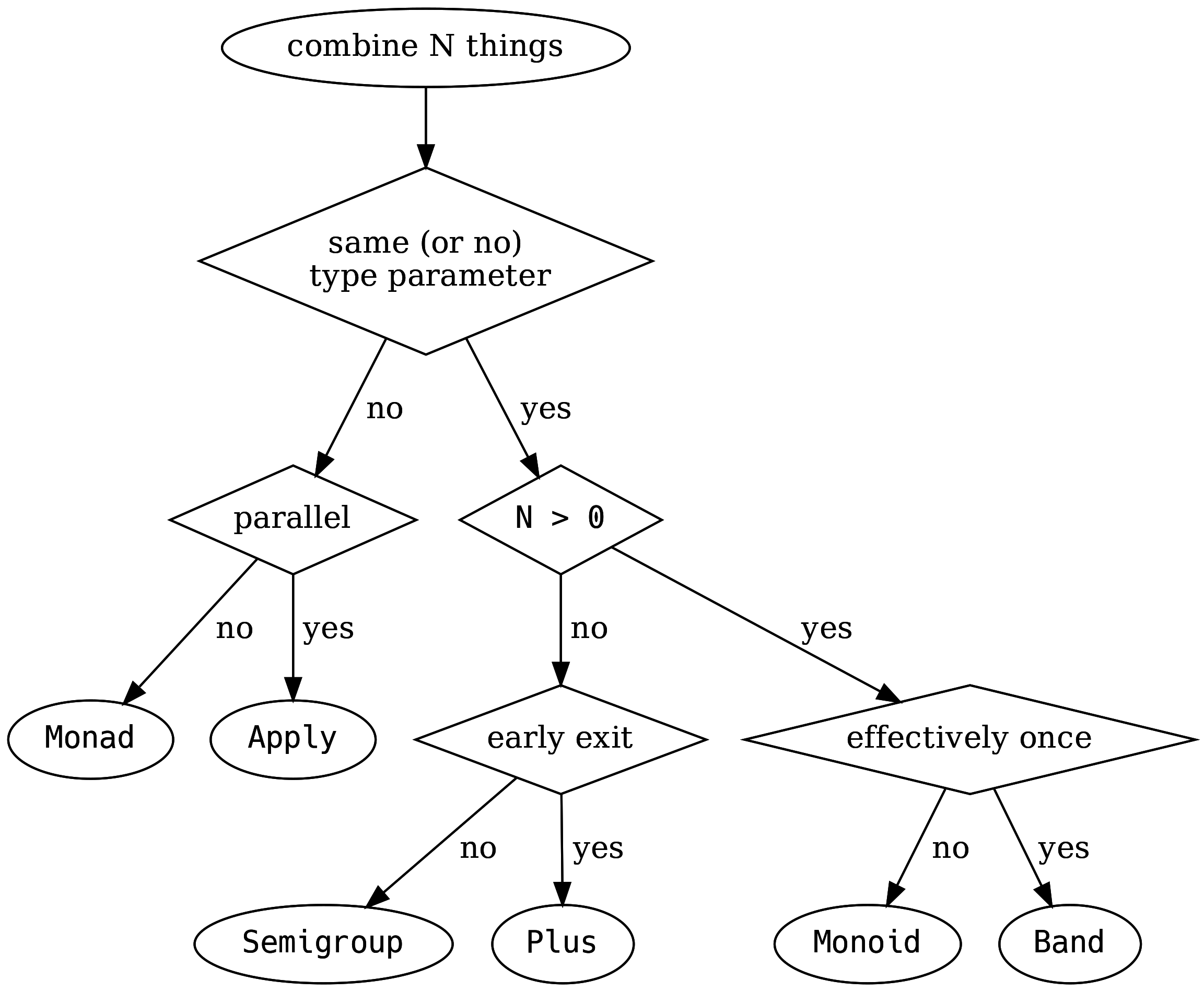

To help further, Valentin Kasas explains how to combine N things: