3. Application Design

In this chapter we will write the business logic and tests for a purely

functional server application. The source code for this application is included

under the example directory along with the book’s source, however it is

recommended not to read the source code until the final chapter as there will be

significant refactors as we learn more about FP.

3.1 Specification

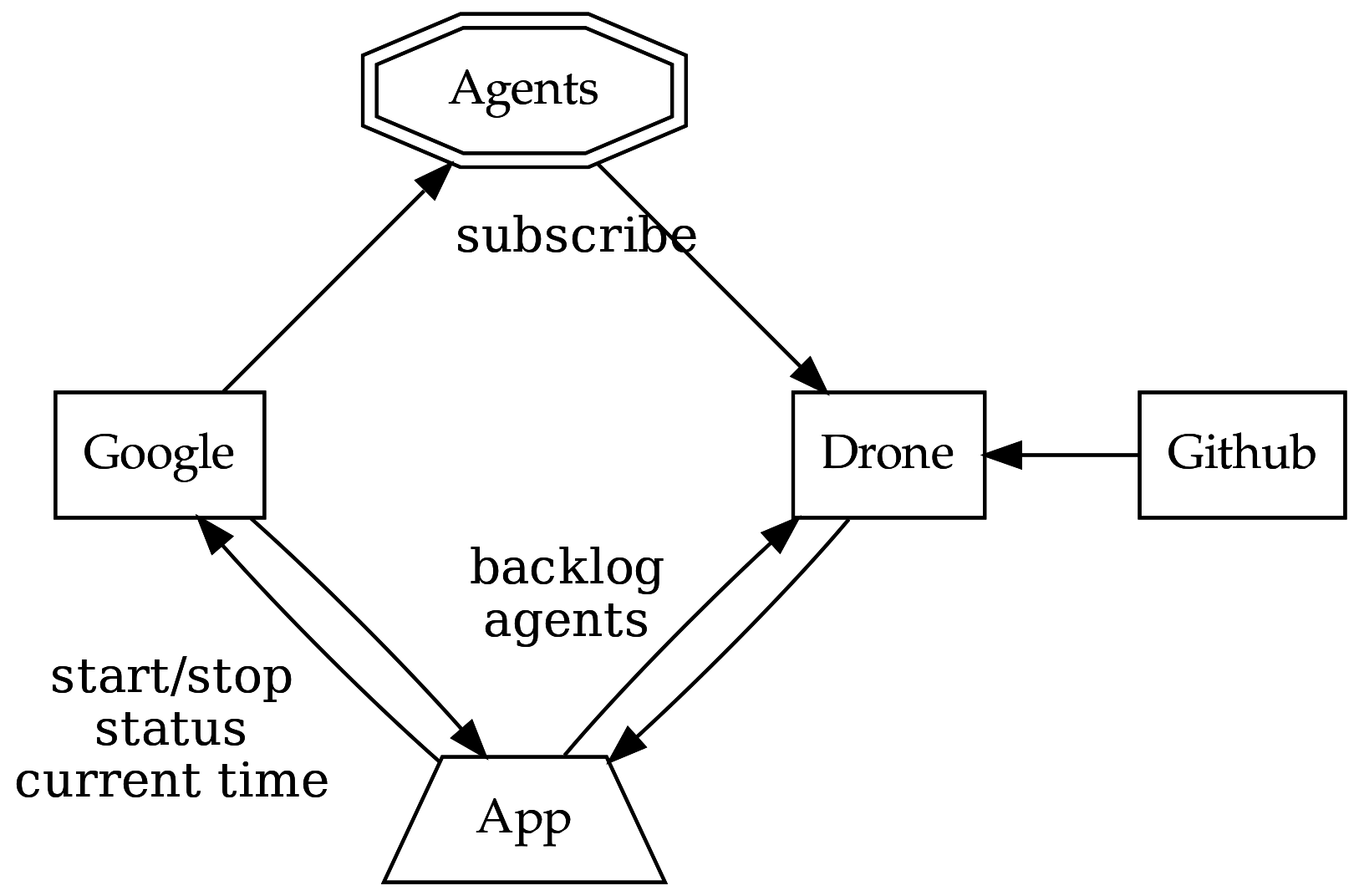

Our application will manage a just-in-time build farm on a shoestring budget. It will listen to a Drone Continuous Integration server, and spawn worker agents using Google Container Engine (GKE) to meet the demand of the work queue.

Drone receives work when a contributor submits a github pull request to a managed project. Drone assigns the work to its agents, each processing one job at a time.

The goal of our app is to ensure that there are enough agents to complete the work, with a cap on the number of agents, whilst minimising the total cost. Our app needs to know the number of items in the backlog and the number of available agents.

Google can spawn nodes, each can host multiple drone agents. When an agent starts up, it registers itself with drone and drone takes care of the lifecycle (including keep-alive calls to detect removed agents).

GKE charges a fee per minute of uptime, rounded up to the nearest hour for each node. One does not simply spawn a new node for each job in the work queue, we must re-use nodes and retain them until their 59th minute to get the most value for money.

Our app needs to be able to start and stop nodes, as well as check their status (e.g. uptimes, list of inactive nodes) and to know what time GKE believes it to be.

In addition, there is no API to talk directly to an agent so we do not know if any individual agent is performing any work for the drone server. If we accidentally stop an agent whilst it is performing work, it is inconvenient and requires a human to restart the job.

Contributors can manually add agents to the farm, so counting agents and nodes is not equivalent. We don’t need to supply any nodes if there are agents available.

The failure mode should always be to take the least costly option.

Both Drone and GKE have a JSON over REST API with OAuth 2.0 authentication.

3.2 Interfaces / Algebras

Let’s codify the architecture diagram from the previous section. Firstly, we need a need a simple data type to capture a millisecond timestamp because such a simple thing does not exist in either the Java or Scala standard libraries:

In FP, an algebra takes the place of an interface in Java, or the

set of valid messages for an Actor in Akka. This is the layer where

we define all side-effecting interactions of our system.

There is tight iteration between writing the business logic and the algebra: it is a good level of abstraction to design a system.

We’ve used NonEmptyList, easily created by calling .toNel on the

stdlib’s List (returning an Option[NonEmptyList]), otherwise

everything should be familiar.

3.3 Business Logic

Now we write the business logic that defines the application’s behaviour, considering only the happy path.

First, the imports

We need a WorldView class to hold a snapshot of our knowledge of the

world. If we were designing this application in Akka, WorldView

would probably be a var in a stateful Actor.

WorldView aggregates the return values of all the methods in the

algebras, and adds a pending field to track unfulfilled requests.

Now we are ready to write our business logic, but we need to indicate

that we depend on Drone and Machines.

We can write the interface for the business logic

and implement it with a module. A module depends only on other modules,

algebras and pure functions, and can be abstracted over F. If an

implementation of an algebraic interface is tied to a specific type, e.g. IO,

it is called an interpreter.

The Monad context bound means that F is monadic, allowing us to use map,

pure and, of course, flatMap via for comprehensions.

We have access to the algebra of Drone and Machines as D and M,

respectively. Using a single capital letter name is a common naming convention

for monad and algebra implementations.

Our business logic will run in an infinite loop (pseudocode)

We must write three functions: initial, update and act, all

returning an F[WorldView].

3.3.1 initial

In initial we call all external services and aggregate their results

into a WorldView. We default the pending field to an empty Map.

Recall from Chapter 1 that flatMap (i.e. when we use the <-

generator) allows us to operate on a value that is computed at

runtime. When we return an F[_] we are returning another program to

be interpreted at runtime, that we can then flatMap. This is how we

safely chain together sequential side-effecting code, whilst being

able to provide a pure implementation for tests. FP could be described

as Extreme Mocking.

3.3.2 update

update should call initial to refresh our world view, preserving

known pending actions.

If a node has changed state, we remove it from pending and if a

pending action is taking longer than 10 minutes to do anything, we

assume that it failed and forget that we asked to do it.

Pure functions don’t need test mocks, they have explicit inputs and outputs, so

we could move all pure code into standalone methods on a stateless object,

testable in isolation. We’re happy testing only the public methods, preferring

that our business logic is easy to read.

3.3.3 act

The act method is slightly more complex, so we’ll split it into two

parts for clarity: detection of when an action needs to be taken,

followed by taking action. This simplification means that we can only

perform one action per invocation, but that is reasonable because we

can control the invocations and may choose to re-run act until no

further action is taken.

We write the scenario detectors as extractors for WorldView, which

is nothing more than an expressive way of writing if / else

conditions.

We need to add agents to the farm if there is a backlog of work, we have no agents, we have no nodes alive, and there are no pending actions. We return a candidate node that we would like to start:

If there is no backlog, we should stop all nodes that have become stale (they are not doing any work). However, since Google charge per hour we only shut down machines in their 58th+ minute to get the most out of our money. We return the non-empty list of nodes to stop.

As a financial safety net, all nodes should have a maximum lifetime of 5 hours.

Now that we have detected the scenarios that can occur, we can write

the act method. When we schedule a node to be started or stopped, we

add it to pending noting the time that we scheduled the action.

Because NeedsAgent and Stale do not cover all possible situations,

we need a catch-all case _ to do nothing. Recall from Chapter 2 that

.pure creates the for’s (monadic) context from a value.

foldLeftM is like foldLeft over nodes, but each iteration of the

fold may return a monadic value. In our case, each iteration of the

fold returns F[WorldView].

The M is for Monadic and you will find more of these lifted

methods that behave as one would expect, taking monadic values in

place of values.

3.4 Unit Tests

The FP approach to writing applications is a designer’s dream: you can delegate writing the implementations of algebras to your team members while focusing on making your business logic meet the requirements.

Our application is highly dependent on timing and third party webservices. If this was a traditional OOP application, we’d create mocks for all the method calls, or test actors for the outgoing mailboxes. FP mocking is equivalent to providing an alternative implementation of dependency algebras. The algebras already isolate the parts of the system that need to be mocked — everything else is pure.

We’ll start with some test data

We implement algebras by extending Drone and Machines with a specific

monadic context, Id being the simplest.

Our “mock” implementations simply play back a fixed WorldView. We’ve

isolated the state of our system, so we can use var to store the

state:

When we write a unit test (here using FlatSpec from scalatest), we create an

instance of Mutable and then import all of its members.

Our implicit drone and machines both use the Id execution

context and therefore interpreting this program with them returns an

Id[WorldView] that we can assert on.

In this trivial case we just check that the initial method returns

the same value that we use in the static implementations:

We can create more advanced tests of the update and act methods,

helping us flush out bugs and refine the requirements:

It would be boring to go through the full test suite. Convince yourself with a thought experiment that the following tests are easy to implement using the same approach:

- not request agents when pending

- don’t shut down agents if nodes are too young

- shut down agents when there is no backlog and nodes will shortly incur new costs

- not shut down agents if there are pending actions

- shut down agents when there is no backlog if they are too old

- shut down agents, even if they are potentially doing work, if they are too old

- ignore unresponsive pending actions during update

All of these tests are synchronous and isolated to the test runner’s thread (which could be running tests in parallel). If we’d designed our test suite in Akka, our tests would be subject to arbitrary timeouts and failures would be hidden in logfiles.

The productivity boost of simple tests for business logic cannot be overstated. Consider that 90% of an application developer’s time interacting with the customer is in refining, updating and fixing these business rules. Everything else is implementation detail.

3.5 Parallel

The application that we have designed runs each of its algebraic methods sequentially. But there are some obvious places where work can be performed in parallel.

3.5.1 initial

In our definition of initial we could ask for all the information we

need at the same time instead of one query at a time.

As opposed to flatMap for sequential operations, scalaz uses

Apply syntax for parallel operations:

which can also use infix notation:

If each of the parallel operations returns a value in the same monadic

context, we can apply a function to the results when they all return.

Rewriting update to take advantage of this:

3.5.2 act

In the current logic for act, we are stopping each node

sequentially, waiting for the result, and then proceeding. But we

could stop all the nodes in parallel and then update our view of the

world.

A disadvantage of doing it this way is that any failures will cause us

to short-circuit before updating the pending field. But that’s a

reasonable tradeoff since our update will gracefully handle the case

where a node is shut down unexpectedly.

We need a method that operates on NonEmptyList that allows us to

map each element into an F[MachineNode], returning an

F[NonEmptyList[MachineNode]]. The method is called traverse, and

when we flatMap over it we get a NonEmptyList[MachineNode] that we

can deal with in a simple way:

Arguably, this is easier to understand than the sequential version.

3.5.3 Parallel Interpretation

Marking something as suitable for parallel execution does not guarantee that it

will be executed in parallel: that is the responsibility of the implementation.

Not to state the obvious: parallel execution is supported by Future, but not

Id.

Of course, we need to be careful when implementing algebras such that they can perform operations safely in parallel, perhaps requiring protecting internal state with concurrency locks or actors.

3.6 Summary

- algebras define the interface between systems.

- modules define pure logic and depend on algebras and other modules.

- Test implementations can mock out the side-effecting parts of the system, enabling a high level of test coverage for the business logic.

- algebraic methods can be performed in parallel by taking their product or traversing sequences (caveat emptor, revisited later).