7. Advanced Monads

You have to know things like Advanced Monads in order to be an advanced

functional programmer. However, we are developers yearning for a simple life,

and our idea of “advanced” is modest. To put it into context:

scala.concurrent.Future is more complicated and nuanced than any Monad in

this chapter.

In this chapter we will study some of the most important implementations of

Monad and explain why Future needlessly complicates an application: we will

offer simpler and faster alternatives.

7.1 Always in motion is the Future

The biggest problem with Future is that it eagerly schedules work during

construction. As we discovered in the introduction, Future conflates the

definition of a program with interpreting it (i.e. running it).

Future is also bad from a performance perspective: every time .flatMap is

called, a closure is submitted to an Executor, resulting in unnecessary thread

scheduling and context switching. It is not unusual to see 50% of our CPU power

dealing with thread scheduling, instead of doing the work. So much so that

parallelising work with Future can often make it slower.

Combined, eager evaluation and executor submission means that it is impossible to know when a job started, when it finished, or the sub-tasks that were spawned to calculate the final result. It should not surprise us that performance monitoring “solutions” are a solid earner for the modern day snake oil merchant.

Furthermore, Future.flatMap requires an ExecutionContext to be in implicit

scope: users are forced to think about business logic and execution semantics at

the same time.

7.2 Effects and Side Effects

If we can’t call side-effecting methods in our business logic, or in Future

(or Id, or Either, or Const, etc), when can we write them? The answer

is: in a Monad that delays execution until it is interpreted at the

application’s entrypoint. We can now refer to I/O and mutation as an effect on

the world, captured by the type system, as opposed to having a hidden

side-effect.

The simplest implementation of such a Monad is IO, formalising the version

we wrote in the introduction:

The .interpret method is only called once, in the entrypoint of an

application:

However, there are two big problems with this simple IO:

- it can stack overflow

- it doesn’t support parallel computations

Both of these problems will be overcome in this chapter. However, no matter how

complicated the internal implementation of a Monad, the principles described

here remain true: we’re modularising the definition of a program and its

execution, such that we can capture effects in type signatures, allowing us to

reason about them, and reuse more code.

7.3 Stack Safety

On the JVM, every method call adds an entry to the call stack of the Thread,

like adding to the front of a List. When the method completes, the method at

the head is thrown away. The maximum length of the call stack is determined by

the -Xss flag when starting up java. Tail recursive methods are detected by

the scala compiler and do not add an entry. If we hit the limit, by calling too

many chained methods, we get a StackOverflowError.

Unfortunately, every nested call to our IO’s .flatMap adds another method

call to the stack. The easiest way to see this is to repeat an action forever,

and see if it survives for longer than a few seconds. We can use .forever,

from Apply (a parent of Monad):

Scalaz has a typeclass that Monad instances can implement if they are stack

safe: BindRec requires a constant stack space for recursive bind:

We don’t need BindRec for all programs, but it is essential for a general

purpose Monad implementation.

The way to achieve stack safety is to convert method calls into references to an

ADT, the Free monad:

The Free monad is named because it can be generated for free for any S[_].

For example, we could set S to be the Drone or Machines algebras from

Chapter 3 and generate a data structure representation of our program. We’ll

return to why this is useful at the end of this chapter.

7.3.1 Trampoline

Free is more general than we need for now. Setting the algebra S[_] to ()

=> ?, a deferred calculation or thunk, we get Trampoline and can implement

a stack safe Monad

The Free ADT is a natural data type representation of the Monad interface:

-

Returnrepresents.point -

Gosubrepresents.bind/.flatMap

When an ADT mirrors the arguments of related functions, it is called a Church encoding.

The BindRec implementation, .tailrecM, runs .bind until we get a B.

Although this is not technically a @tailrec implementation, it uses constant

stack space because each call returns a heap object, with delayed recursion.

Convenient functions are provided to create a Trampoline eagerly (.done) or

by-name (.delay). We can also create a Trampoline from a by-name

Trampoline (.suspend):

When we see Trampoline[A] in a codebase we can always mentally substitute it

with A, because it is simply adding stack safety to the pure computation. We

get the A by interpreting Free, provided by .run.

7.3.2 Example: Stack Safe DList

In the previous chapter we described the data type DList as

However, the actual implementation looks more like:

Instead of applying nested calls to f we use a suspended Trampoline. We

interpret the trampoline with .run only when needed, e.g. in toIList. The

changes are minimal, but we now have a stack safe DList that can rearrange the

concatenation of a large number lists without blowing the stack!

7.3.3 Stack Safe IO

Similarly, our IO can be made stack safe thanks to Trampoline:

The interpreter, .unsafePerformIO(), has an intentionally scary name to

discourage using it except in the entrypoint of the application.

This time, we don’t get a stack overflow error:

Using a Trampoline typically introduces a performance regression vs a regular

reference. It is Free in the sense of freely generated, not free as in

beer.

7.4 Monad Transformer Library

Monad transformers are data structures that wrap an underlying value and provide a monadic effect.

For example, in Chapter 2 we used OptionT to let us use F[Option[A]] in a

for comprehension as if it was just a F[A]. This gave our program the effect

of an optional value. Alternatively, we can get the effect of optionality if

we have a MonadPlus.

This subset of data types and extensions to Monad are often referred to as the

Monad Transformer Library (MTL), summarised below. In this section, we will

explain each of the transformers, why they are useful, and how they work.

| Effect | Underlying | Transformer | Typeclass |

|---|---|---|---|

| optionality | F[Maybe[A]] |

MaybeT |

MonadPlus |

| errors | F[E \/ A] |

EitherT |

MonadError |

| a runtime value | A => F[B] |

ReaderT |

MonadReader |

| journal / multitask | F[(W, A)] |

WriterT |

MonadTell |

| evolving state | S => F[(S, A)] |

StateT |

MonadState |

| keep calm & carry on | F[E \&/ A] |

TheseT |

|

| control flow | (A => F[B]) => F[B] |

ContT |

7.4.1 MonadTrans

Each transformer has the general shape T[F[_], A], providing at least an

instance of Monad and Hoist (and therefore MonadTrans):

.liftM lets us create a monad transformer if we have an F[A]. For example,

we can create an OptionT[IO, String] by calling .liftM[OptionT] on an

IO[String].

.hoist is the same idea, but for natural transformations.

Generally, there are three ways to create a monad transformer:

- from the underlying, using the transformer’s constructor

- from a single value

A, using.purefrom theMonadsyntax - from an

F[A], using.liftMfrom theMonadTranssyntax

Due to the way that type inference works in Scala, this often means that a complex type parameter must be explicitly written. As a workaround, transformers provide convenient constructors on their companion that are easier to use.

7.4.2 MaybeT

OptionT, MaybeT and LazyOptionT have similar implementations, providing

optionality through Option, Maybe and LazyOption, respectively. We will

focus on MaybeT to avoid repetition.

providing a MonadPlus

This monad looks fiddly, but it is just delegating everything to the Monad[F]

and then re-wrapping with a MaybeT. It is plumbing.

With this monad we can write logic that handles optionality in the F[_]

context, rather than carrying around Option or Maybe.

For example, say we are interfacing with a social media website to count the

number of stars a user has, and we start with a String that may or may not

correspond to a user. We have this algebra:

We need to call getUser followed by getStars. If we use Monad as our

context, our function is difficult because we have to handle the Empty case:

However, if we have a MonadPlus as our context, we can suck Maybe into the

F[_] with .orEmpty, and forget about it:

However adding a MonadPlus requirement can cause problems downstream if the

context does not have one. The solution is to either change the context of the

program to MaybeT[F, ?] (lifting the Monad[F] into a MonadPlus), or to

explicitly use MaybeT in the return type, at the cost of slightly more code:

The decision to require a more powerful Monad vs returning a transformer is

something that each team can decide for themselves based on the interpreters

that they plan on using for their program.

7.4.3 EitherT

An optional value is a special case of a value that may be an error, but we

don’t know anything about the error. EitherT (and the lazy variant

LazyEitherT) allows us to use any type we want as the error value, providing

contextual information about what went wrong.

Where \/ and Validation is the FP equivalent of a checked exception,

EitherT makes it convenient to both create and ignore errors until something

can be done about it.

EitherT is a wrapper around an F[A \/ B]

The Monad is a MonadError

.raiseError and .handleError are self-descriptive: the equivalent of throw

and catch an exception, respectively.

.emap, either map, is for functions that could fail and is very useful for

writing decoders in terms of existing ones, much as we used .contramap to

define new encoders in terms of existing ones. For example, say we have an XML

decoder like

we can define a decoder for Char in terms of a String decoder

The MonadError for EitherT is:

It should be of no surprise that we can rewrite the MonadPlus example with

MonadError, inserting informative error messages:

where .orError is a convenience method on Maybe

The version using EitherT directly looks like

The simplest instance of MonadError is for \/, perfect for testing business

logic that requires a MonadError. For example,

Our unit tests for .stars might cover these cases:

As we’ve now seen several times, we can focus on testing the pure business logic without distraction.

Finally, if we return to our JsonClient algebra from Chapter 4.3

recall that we only coded the happy path into the API. If our interpreter for

this algebra only works for an F having a MonadError we get to define the

kinds of errors as a tangential concern. Indeed, we can have two layers of

error if we define the interpreter for a EitherT[IO, JsonClient.Error, ?]

which cover I/O (network) problems, server status problems, and issues with our modelling of the server’s JSON payloads.

7.4.3.1 Choosing an error type

The community is undecided on the best strategy for the error type E in

MonadError.

One school of thought says that we should pick something general, like a

String. The other school says that an application should have an ADT of

errors, allowing different errors to be reported or handled differently. An

unprincipled gang prefers using Throwable for maximum JVM compatibility.

There are two problems with an ADT of errors on the application level:

- it is very awkward to create a new error. One file becomes a monolithic repository of errors, aggregating the ADTs of individual subsystems.

- no matter how granular the errors are, the resolution is often the same: log it and try it again, or give up. We don’t need an ADT for this.

An error ADT is of value if every entry allows a different kind of recovery to be performed.

A compromise between an error ADT and a String is an intermediary format. JSON

is a good choice as it can be understood by most logging and monitoring

frameworks.

A problem with not having a stacktrace is that it can be hard to localise which

piece of code was the source of an error. With sourcecode by Li Haoyi, we can

include contextual information as metadata in our errors:

Although Err is referentially transparent, the implicit construction of a

Meta does not appear to be referentially transparent from a natural reading:

two calls to Meta.gen (invoked implicitly when creating an Err) will produce

different values because the location in the source code impacts the returned

value:

To understand this, we have to appreciate that sourcecode.* methods are macros

that are generating source code for us. If we were to write the above explicitly

it is clear what is happening:

Yes, we’ve made a deal with the macro devil, but we could also write the Meta

manually and have it go out of date quicker than our documentation.

7.4.3.2 IO and Throwable

IO does not have a MonadError but instead implements something similar to

throw, catch and finally for Throwable errors:

It is good to avoid using keywords where possible, as it means we have to

remember less caveats of the language. If we need to interact with a legacy API

with a predictable exception, like a string parser, we can use Maybe.attempt

or \/.attempt and convert the non referentially transparent Throwable into a

descriptive String.

7.4.4 ReaderT

The reader monad wraps A => F[B] allowing a program F[B] to depend on a

runtime value A. For those familiar with dependency injection, the reader

monad is the FP equivalent of Spring or Guice’s @Inject, without the XML and

reflection.

ReaderT is just an alias to another more generally useful data type named

after the mathematician Heinrich Kleisli.

An implicit conversion on the companion allows us to use a Kleisli in place

of a function, so we can provide it as the parameter to a monad’s .bind, or

>>=.

The most common use for ReaderT is to provide environment information to a

program. In drone-dynamic-agents we need access to the user’s Oauth 2.0

Refresh Token to be able to contact Google. The obvious thing is to load the

RefreshTokens from disk on startup, and make every method take an implicit

tokens: RefreshToken. In fact, this is such a common requirement that Martin

Odersky has proposed implicit functions.

A better solution is for our program to have an algebra that provides the configuration when needed, e.g.

We have reinvented MonadReader, the typeclass associated to ReaderT, where

.ask is the same as our .token, and S is RefreshToken:

with the implementation

A law of MonadReader is that the S cannot change between invocations, i.e.

ask >> ask === ask. For our usecase, this is to say that the configuration is

read once. If we decide later that we want to reload configuration every time we

need it, e.g. allowing us to change the token without restarting the

application, we can reintroduce ConfigReader which has no such law.

In our OAuth 2.0 implementation we could first move the Monad evidence onto the

methods:

and then refactor the refresh parameter to be part of the Monad

Fundamentally, any parameter can be moved into the MonadReader. This is of

most value to your immediate caller when they simply want to thread through this

information from above. With ReaderT, we can reserve implicit parameter

blocks entirely for the use of typeclasses, reducing the mental burden of using

Scala.

The other method in MonadReader is .local

We can change S and run a program fa within that local context, returning to

the original S. A use case for .local is to generate a “stack trace” that

makes sense to our domain. giving us nested logging! Leaning on the Meta data

structure from the previous section, we define a function to checkpoint:

and we can use it to wrap functions that operate in this context.

automatically passing through anything that is not explicitly traced. A compiler plugin or macro could do the opposite, opting everything in by default.

If we access .ask we can see the breadcrumb trail of exactly how we were

called, without the distraction of bytecode implementation details. A

referentially transparent stacktrace!

A defensive programmer may wish to truncate the IList[Meta] at a certain

length to avoid the equivalent of a stack overflow. Indeed, a more appropriate

data structure is Dequeue.

.local can also be used to keep track of contextual information that is

directly relevant to the task at hand, like the number of spaces that must

indent a line when pretty printing a human readable file format, bumping it by

two spaces when we enter a nested structure.

Finally, if we cannot request a MonadReader because our application does not

provide one, we can always return a ReaderT

If a caller receives a ReaderT, and they have the token parameter to hand,

they can call access.run(token) and get back an F[BearerToken].

Admittedly, since we don’t have many callers, we should just revert to a regular

function parameter. MonadReader is of most use when:

- we may wish to refactor the code later to reload config

- the value is not needed by intermediate callers

- or, we want to locally scope some variable

In a nutshell, dotty can keep its implicit functions… we already have

ReaderT and MonadReader.

One last example. Monad transformers typically provide specialised Monad

instances if their underlying type has one. So, for example, ReaderT has a

MonadError, MonadPlus, etc if the underlying has one. Decoder typeclasses

tend to have a signature that looks like A => F[B], recall

which has a single method of signature XNode => String \/ A, isomorphic to

ReaderT[String \/ ?, Xml, A]. We can formalise this relationship with an

Isomorphism. It’s easier to read by introducing type aliases

Now our XDecoder has access to all the typeclasses that ReaderT has. The

typeclass we need is MonadError[Decoder, String]

which we know to be useful for defining new decoders in terms of existing ones.

7.4.5 WriterT

The opposite to reading is writing. The WriterT monad transformer is typically

for writing to a journal.

The wrapped type is F[(W, A)] with the journal accumulated in W.

There is not just one associated monad, but two! MonadTell and MonadListen

MonadTell is for writing to the journal and MonadListen is to recover it.

The WriterT implementation is

The most obvious example is to use MonadTell for logging, or audit reporting.

Reusing Meta from our error reporting we could imagine creating a log

structure like

and use Dequeue[Log] as our journal type. We could change our OAuth2

authenticate method to

We could even combine this with the ReaderT traces and get structured logs.

The caller can recover the logs with .written and do something with them.

However, there is a strong argument that logging deserves its own algebra. The log level is often needed at the point of creation for performance reasons and writing out the logs is typically managed at the application level rather than something each component needs to be concerned about.

The W in WriterT has a Monoid, allowing us to journal any kind of

monoidic calculation as a secondary value along with our primary program. For

example, counting the number of times we do something, building up an

explanation of a calculation, or building up a TradeTemplate for a new trade

while we price it.

A popular specialisation of WriterT is when the monad is Id, meaning the

underlying run value is just a simple tuple (W, A).

which allows us to let any value carry around a secondary monoidal calculation,

without needing a context F[_].

In a nutshell, WriterT / MonadTell is how to multi-task in FP.

7.4.6 StateT

StateT lets us .put, .get and .modify a value that is handled by the

monadic context. It is the FP replacement of var.

If we were to write an impure method that has access to some mutable state, held

in a var, it might have the signature () => F[A] and return a different

value on every call, breaking referential transparency. With pure FP the

function takes the state as input and returns the updated state as output, which

is why the underlying type of StateT is S => F[(S, A)].

The associated monad is MonadState

StateT is implemented slightly differently than the monad transformers we have

studied so far. Instead of being a case class it is an ADT with two members:

which are a specialised form of Trampoline, giving us stack safety when we

want to recover the underlying data structure, .run:

StateT can straightforwardly implement MonadState with its ADT:

With .pure mirrored on the companion as .stateT:

and MonadTrans.liftM providing the F[A] => StateT[F, S, A] constructor as

usual.

A common variant of StateT is when F = Id, giving the underlying type

signature S => (S, A). Scalaz provides a type alias and convenience functions

for interacting with the State monad transformer directly, and mirroring

MonadState:

For an example we can return to the business logic tests of

drone-dynamic-agents. Recall from Chapter 3 that we created Mutable as test

interpreters for our application and we stored the number of started and

stoped nodes in var.

We now know that we can write a much better test simulator with State. We’ll

take the opportunity to upgrade the accuracy of the simulation at the same time.

Recall that a core domain object is our application’s view of the world:

Since we’re writing a simulation of the world for our tests, we can create a data type that captures the ground truth of everything

The key difference being that the started and stopped nodes can be separated

out. Our interpreter can be implemented in terms of State[World, a] and we can

write our tests to assert on what both the World and WorldView looks like

after the business logic has run.

The interpreters, which are mocking out contacting external Drone and Google services, may be implemented like this:

and we can rewrite our tests to follow a convention where:

-

world1is the state of the world before running the program -

view1is the application’s belief about the world -

world2is the state of the world after running the program -

view2is the application’s belief after running the program

For example,

We would be forgiven for looking back to our business logic loop

and use StateT to manage the state. However, our DynAgents business logic

requires only Applicative and we would be violating the Rule of Least Power

to require the more powerful MonadState. It is therefore entirely reasonable

to handle the state manually by passing it in to update and act, and let

whoever calls us use a StateT if they wish.

7.4.7 IndexedStateT

The code that we have studied thus far is not how scalaz implements StateT.

Instead, a type alias points to IndexedStateT

The implementation of IndexedStateT is much as we have studied, with an extra

type parameter allowing the input state S1 and output state S2 to differ:

IndexedStateT does not have a MonadState when S1 ! S2=, although it has a

Monad.

The following example is adapted from Index your State by Vincent Marquez.

Consider the scenario where we must design an algebraic interface to access a

key: Int to value: String lookup. This may have a networked implementation

and the order of calls is essential. Our first attempt at the API may look

something like:

with runtime errors if .update or .commit is called without a .lock. A

more complex design may involve multiple traits and a custom DSL that nobody

remembers how to use.

Instead, we can use IndexedStateT to require that the caller is in the correct

state. First we define our possible states as an ADT

and then revisit our algebra

which will give a compiletime error if we try to .update without a .lock

but allowing us to construct functions that can be composed by explicitly including their state:

7.4.8 IndexedReaderWriterStateT

Those wanting to have a combination of ReaderT, WriterT and IndexedStateT

will not be disappointed. The transformer IndexedReaderWriterStateT wraps (R,

S1) => F[(W, A, S2)] with R having Reader semantics, W for monoidic

writes, and the S parameters for indexed state updates.

Abbreviations are provided because otherwise, let’s be honest, these types are so long they look like they are part of a J2EE API:

IRWST is a more efficient implementation than a manually created transformer

stack of ReaderT[WriterT[IndexedStateT[F, ...], ...], ...].

7.4.9 TheseT

TheseT allows errors to either abort the calculation or to be accumulated if

there is some partial success. Hence keep calm and carry on.

The underlying data type is F[A \&/ B] with A being the error type,

requiring a Semigroup to enable the accumulation of errors.

There is no special monad associated with TheseT, it is just a regular

Monad. If we wish to abort a calculation we can return a This value, but we

accumulate errors when we return a Both which also contains a successful part

of the calculation.

TheseT can also be thought of from a different angle: A does not need to be

an error. Similarly to WriterT, the A may be a secondary calculation that

we are computing along with the primary calculation B. TheseT allows early

exit when something special about A demands it, like when Charlie Bucket found

the last golden ticket (A) he threw away his chocolate bar (B).

7.4.10 ContT

Continuation Passing Style (CPS) is a style of programming where functions never return, instead continuing to the next computation. CPS is popular in Javascript and Lisp as they allow non-blocking I/O via callbacks when data is available. A direct translation of the pattern into impure Scala looks like

We can make this pure by introducing an F[_] context

and refactor to return a function for the provided input

ContT is just a container for this signature, with a Monad instance

and convenient syntax to create a ContT from a monadic value:

However, the simple callback use of continuations brings nothing to pure

functional programming because we already know how to sequence non-blocking,

potentially distributed, computations: that’s what Monad is for and we can do

this with .bind or a Kleisli arrow. To see why continuations are useful we

need to consider a more complex example under a rigid design constraint.

7.4.10.1 Control Flow

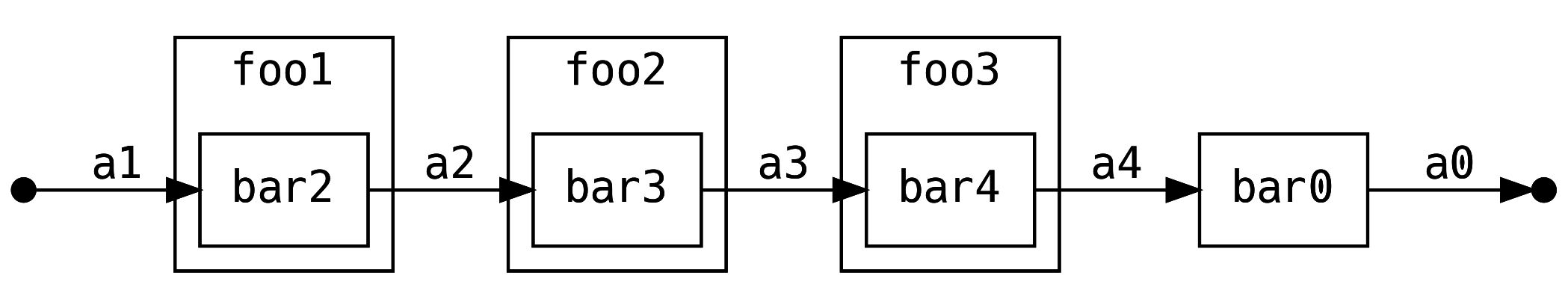

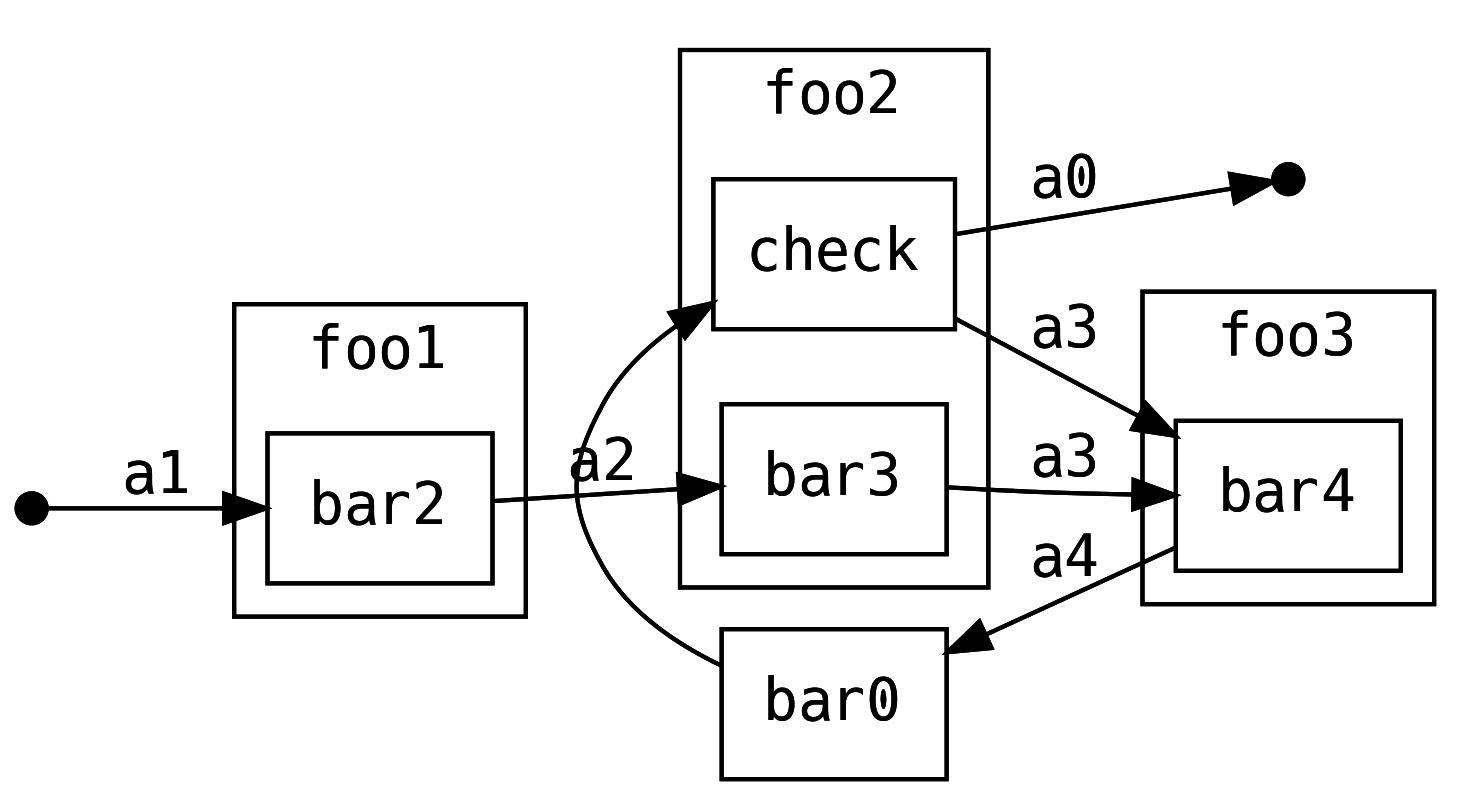

Say we have modularised our application into components that can perform I/O, with each component owned by a different development team:

Our goal is to produce an A0 given an A1. Whereas Javascript and Lisp would

reach for continuations to solve this problem (because the I/O could block) we

can just chain the functions

We can lift .simple into its continuation form by using the convenient .cps

syntax and a little bit of extra boilerplate for each step:

So what does this buy us? Firstly, it’s worth noting that the control flow of this application is left to right

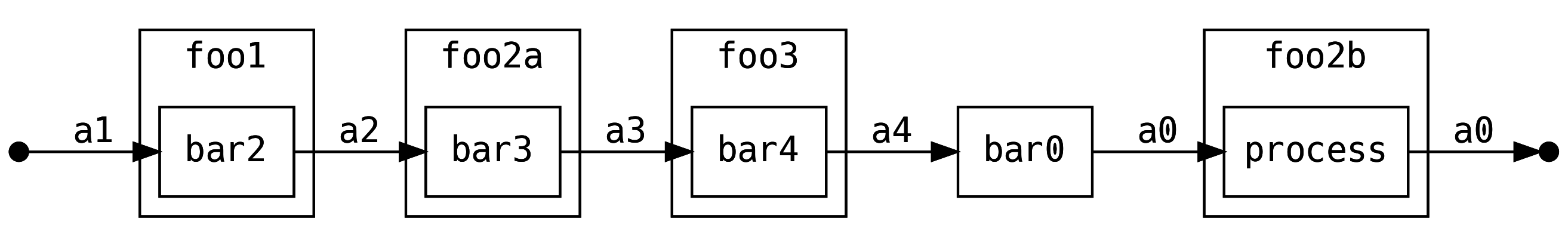

What if we are the authors of foo2 and we want to post-process the a0 that

we receive from the right (downstream), i.e. we want to split our foo2 into

foo2a and foo2b

Let’s add the constraint that we cannot change the definition of flow or

bar0, perhaps it is not our code and is defined by the framework we are

using.

It is not possible to process the output of a0 by modifying any of the

remaining barX methods. However, with ContT we can modify foo2 to process

the result of the next continuation:

Which can be defined with

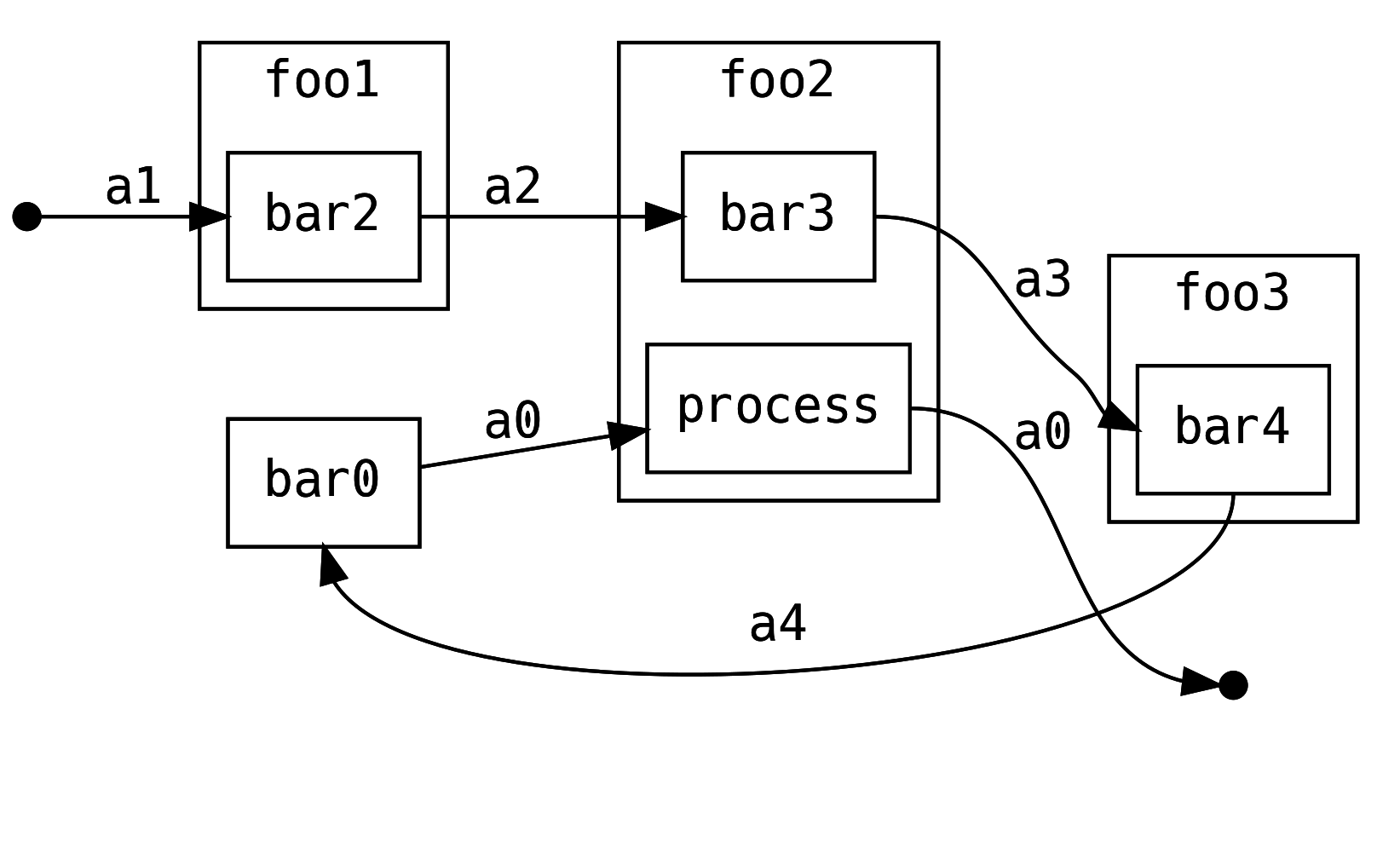

We are not limited to .map over the return value, we can .bind into another

control flow turning the linear flow into a graph!

Or we can stay within the original flow and retry everything downstream

This is just one retry, not an infinite loop. For example, we might want downstream to reconfirm a potentially dangerous action.

Finally, we can perform actions that are specific to the context of the ContT,

in this case IO which lets us do error handling and resource cleanup:

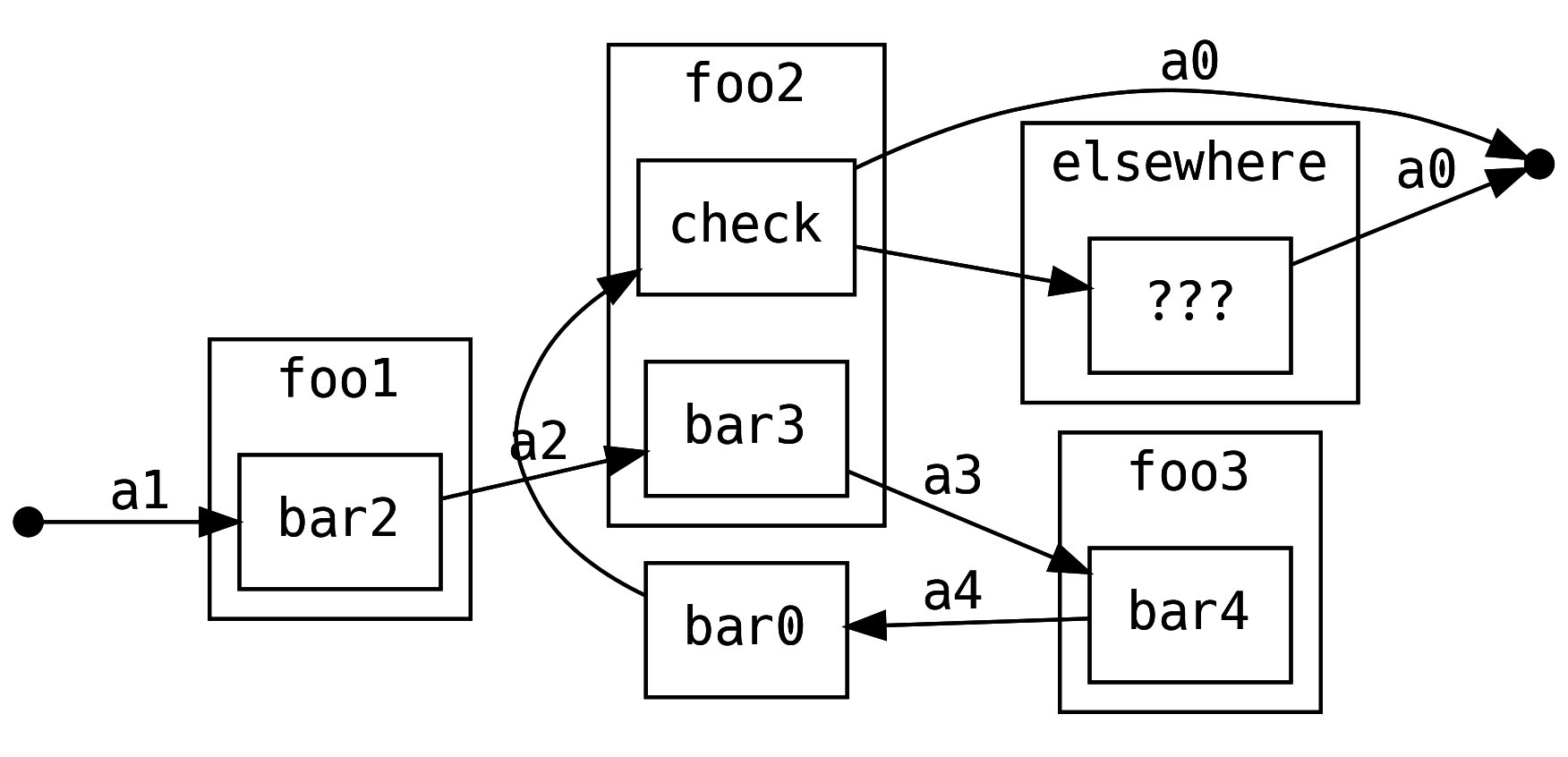

7.4.10.2 When to Order Spaghetti

It is not an accident that these diagrams look like spaghetti, that’s just what

happens when we start messing with control flow. All the mechanisms we’ve

discussed in this section are simple to implement directly if we can edit the

definition of flow, therefore we do not typically need to use ContT.

However, if we are designing a framework, we should consider exposing the plugin

system as ContT callbacks to allow our users more power over their control

flow. Sometimes the customer just really wants the spaghetti.

For example, if the Scala compiler was written using CPS, it would allow for a principled approach to communication between compiler phases. A compiler plugin would be able to perform some action based on the inferred type of an expression, computed at a later stage in the compile. Similarly, continuations would be a good API for an extensible build tool or text editor.

A caveat with ContT is that it is not stack safe, so cannot be used for

programs that run forever.

7.4.10.3 Great, kid. Don’t get ContT.

A more complex variant of ContT called IndexedContT wraps (A => F[B]) =>

F[C]. The new type parameter C allows the return type of the entire

computation to be different to the return type between each component. But if

B is not equal to C then there is no Monad.

Not missing an opportunity to generalise as much as possible, IndexedContT is

actually implemented in terms of an even more general structure (note the extra

s before the T)

where W[_] has a Comonad, and ContT is actually implemented as a type

alias. Companion objects exist for these type aliases with convenient

constructors.

Admittedly, five type parameters is perhaps a generalisation too far. But then again, over-generalisation is consistent with the sensibilities of continuations.

7.4.11 Transformer Stacks and Ambiguous Implicits

This concludes our tour of the monad transformers in scalaz.

When multiple transformers are combined, we call this a transformer stack and

although it is verbose, it is possible to read off the features by reading the

transformers. For example if we construct an F[_] context which is a set of

composed transformers, such as

we know that we are adding error handling with error type E (there is a

MonadError[Ctx, E]) and we are managing state A (there is a MonadState[Ctx,

S]).

But there are unfortunately practical drawbacks to using monad transformers and

their companion Monad typeclasses:

- Multiple implicit

Monadparameters mean that the compiler cannot find the correct syntax to use for the context. - Monads do not compose in the general case, which means that the order of nesting of the transformers is important.

- All the interpreters must be lifted into the common context. For example, we

might have an implementation of some algebra that uses for

IOand now we need to wrap it withStateTandEitherTeven though they are unused inside the interpreter. - There is a performance cost associated to each layer. And some monad

transformers are worse than others.

StateTis particularly bad but evenEitherTcan cause memory allocation problems for high throughput applications.

Let’s talk about workarounds.

7.4.11.1 No Syntax

Let’s say we have an algebra

and some data types

that we want to use in our business logic

The first problem we encounter is that this fails to compile

There are some tactical solutions to this problem. The most obvious is to make all the parameters explicit

and require only Monad to be passed implicitly via context bounds. However,

this means that we must manually wire up the MonadError and MonadState when

calling foo1 and when calling out to another method that requires an

implicit.

A second solution is to leave the parameters implicit and use name shadowing

to make all but one of the parameters explicit. This allows upstream to use

implicit resolution when calling us but we still need to pass parameters

explicitly if we call out.

or we could shadow just one Monad, leaving the other one to provide our syntax

and to be available for when we call out to other methods

A third option, with a higher up-front cost, is to create a custom Monad

typeclass that holds implicit references to the two Monad classes that we

care about

and a derivation of the typeclass given a MonadError and MonadState

Now if we want access to S or E we get them via F.S or F.E

Like the second solution, we can choose one of the Monad instances to be

implicit within the block, achieved by importing it

7.4.11.2 Composing Transformers

An EitherT[StateT[...], ...] has a MonadError but does not have a

MonadState, whereas StateT[EitherT[...], ...] can provide both.

The workaround is to study the implicit derivations on the companion of the transformers and to make sure that the outer most transformer provides everything we need.

A rule of thumb is that more complex transformers go on the outside, with this chapter presenting transformers in increasing order of complex.

7.4.11.3 Lifting Interpreters

Continuing the same example, let’s say our Lookup algebra has an IO

interpreter

but we want our context to be

to give us a MonadError and a MonadState. This means we need to wrap

LookupRandom to operate over Ctx.

Firstly, we want to make use of the .liftM syntax on Monad, which uses

MonadTrans to lift from our starting F[A] into G[F, A]

It is important to realise that the type parameters to .liftM have two type

holes, one of shape _[_] and another of shape _. If we create type aliases

of this shape

We can abstract over MonadTrans to lift a Lookup[F] to any Lookup[G[F, ?]]

where G is a Monad Transformer:

Allowing us to wrap once for EitherT, and then again for StateT

Another way to achieve this, in a single step, is to use MonadIO which enables

lifting an IO into a transformer stack:

with MonadIO instances for all the common combinations of transformers.

The boilerplate overhead to lift an IO interpreter to anything with a

MonadIO instance is therefore two lines of code (for the interpreter

definition), plus one line per element of the algebra, and a final line to call

it:

7.4.11.4 Performance

The biggest problem with Monad Transformers is their performance overhead.

EitherT has a reasonably low overhead, with every .flatMap call generating a

handful of objects, but this can impact high throughput applications where every

object allocation matters. Other transformers, such as StateT, effectively add

a trampoline, and ContT keeps the entire call-chain retained in memory.

If performance becomes a problem, the solution is to not use Monad Transformers.

At least not the transformer data structures. A big advantage of the Monad

typeclasses, like MonadState is that we can create an optimised F[_] for our

application that provides the typeclasses naturally. We will learn how to create

an optimal F[_] over the next two chapters, when we deep dive into two

structures which we have already seen: Free and IO.

7.5 A Free Lunch

Our industry craves safe high-level languages, trading developer efficiency and reliability for reduced runtime performance.

The Just In Time (JIT) compiler on the JVM performs so well that simple functions can have comparable performance to their C or C++ equivalents, ignoring the cost of garbage collection. However, the JIT only performs low level optimisations: branch prediction, inlining methods, unrolling loops, and so on.

The JIT does not perform optimisations of our business logic, for example batching network calls or parallelising independent tasks. The developer is responsible for writing the business logic and optimisations at the same time, reducing readability and making it harder to maintain. It would be good if optimisation was a tangential concern.

If instead, we have a data structure that describes our business logic in terms of high level concepts, not machine instructions, we can perform high level optimisation. Data structures of this nature are typically called Free structures and can be generated for free for the members of the algebraic interfaces of our program. For example, a Free Applicative can be generated that allows us to batch or de-duplicate expensive network I/O.

In this section we will learn how to create free structures, and how they can be used.

7.5.1 Free (Monad)

Fundamentally, a monad describes a sequential program where every step depends on the previous one. We are therefore limited to modifications that only know about things that we’ve already run and the next thing we are going to run.

As a refresher, Free is the data structure representation of a Monad and is

defined by three members

-

Suspendrepresents a program that has not yet been interpreted -

Returnis.pure -

Gosubis.bind

A Free[S, A] can be freely generated for any algebra S. To make this

explicit, consider our application’s Machines algebra

We define a freely generated Free for Machines by creating a GADT with a

data type for each element of the algebra. Each data type has the same input

parameters as its corresponding element, is parameterised over the return type,

and has the same name:

The GADT defines an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) because each member is representing a computation in a program.

We then define .liftF, an implementation of Machines, with Free[Ast, ?] as

the context. Every method simply delegates to Free.liftT to create a Suspend

When we construct our program, parameterised over a Free, we run it by

providing an interpreter (a natural transformation Ast ~> M) to the

.foldMap method. For example, if we could provide an interpreter that maps to

IO we can construct an IO[Unit] program via the free AST

For completeness, an interpreter that delegates to a direct implementation is

easy to write. This might be useful if the rest of the application is using

Free as the context and we already have an IO implementation that we want to

use:

But our business logic needs more than just Machines, we also need access to

the Drone algebra, recall defined as

What we want is for our AST to be a combination of the Machines and Drone

ASTs. We studied Coproduct in Chapter 6, a higher kinded disjunction:

Now we can use the context Free[Coproduct[Machines.Ast, Drone.Ast, ?], ?].

We could manually create the coproduct but we would be swimming in boilerplate, and we’d have to do it all again if we wanted to add a third algebra.

The scalaz.Inject typeclass helps:

The implicit derivations generate Inject instances when we need them,

letting us rewrite our liftF to work for any combination of ASTs:

It is nice that F :<: G reads as if our Ast is a member of the complete F

instruction set: this syntax is intentional.

Putting it all together, lets say we have a program that we wrote abstracting over Monad

and we have some existing implementations of Machines and Drone, we can

create interpreters from them:

and combine them into the larger instruction set using a convenience method from

the NaturalTransformation companion

Then use it to produce an IO

But we’ve gone in circles! We could have used IO as the context for our

program in the first place and avoided Free. So why did we put ourselves

through all this pain? Let’s see some reasons why Free might be useful.

7.5.1.1 Testing: Mocks and Stubs

It might sound hypocritical to propose that Free can be used to reduce

boilerplate, given how much code we have written. However, there is a tipping

point where the Ast pays for itself when we have many tests that require stub

implementations.

If the .Ast and .liftF is defined for an algebra, we can create partial

interpreters

which can be used to test our program

By using partial functions, and not total functions, we are exposing ourselves to runtime errors. Many teams are happy to accept this risk in their unit tests since the test would fail if there is a programmer error.

Arguably we could also achieve the same thing with implementations of our

algebras that implement every method with ???, overriding what we need on a

case by case basis.

7.5.1.2 Monitoring

It is typical for server applications to be monitored by runtime agents that manipulate bytecode to insert profilers and extract various kinds of usage or performance information.

If our application’s context is Free, we do not need to resort to bytecode

manipulation, we can instead implement a side-effecting monitor as an

interpreter that we have complete control over.

For example, consider using this Ast ~> Ast “agent”

which records method invocations: we would use a vendor-specific routine in real code. We could also watch for specific messages of interest and log them as a debugging aid.

We can attach Monitor to our production Free application with

or combine the natural transformations and run with a single

7.5.1.3 Monkey Patching: Part 1

As engineers, we know that our business users often ask for bizarre workarounds to be added to the core logic of the application. We might want to codify such corner cases as exceptions to the rule and handle them tangentially to our core logic.

For example, suppose we get a memo from accounting telling us

URGENT: Bob is using node

#c0ffeeto run the year end. DO NOT STOP THIS MACHINE!1!

There is no possibility to discuss why Bob shouldn’t be using our machines for his super-important accounts, so we have to hack our business logic and put out a release to production as soon as possible.

Our monkey patch can map into a Free structure, allowing us to return a

pre-canned result (Free.pure) instead of scheduling the instruction. We

special case the instruction in a custom natural transformation with its return

value:

eyeball that it works, push it to prod, and set an alarm for next week to remind us to remove it, and revoke Bob’s access to our servers.

Our unit test could use State as the target context, so we can keep track of

all the nodes we stopped:

along with a test that “normal” nodes are not affected.

An advantage of using Free to avoid stopping the #c0ffee nodes is that we

can be sure to catch all the usages instead of having to go through the business

logic and look for all usages of .stop. If our application context is just an

IO we could, of course, implement this logic in the Machines[IO]

implementation but an advantage of using Free is that we don’t need to touch

the existing code and can instead isolate and test this (temporary) behaviour,

without being tied to the IO implementations.

7.5.1.4 Monkey Patching: Part 2

Infrastructure sends a memo:

To meet the CEO’s vision for this quarter, we are on a cost rationalisation and reorientation initiative.

Therefore, we paid Google a million dollars to develop a Batch API so we can start nodes more cost effectively.

PS: Your bonus depends on using the new API.

When we monkey patch, we are not limited to the original instruction set: we can

introduce new ASTs. Rather than change our core business logic, we might decide

to translate existing instructions into an extended set, introducing Batch:

Let’s first set up a test for a simple program by defining the AST and target type:

We track the started nodes in a data container so we can assert on them later

and introduce some stub implementations

We can expect that the following simple program will behave as expected and call

Machines.Start twice:

But we don’t want to use Machines.Start, we need Batch.Start to get

our bonus. Expand the AST to keep track of the Waiting nodes that we are

delaying, and add the Batch instructions:

along with a stub for the Batch algebra

We can convert from the Orig AST into Patched by providing a natural

transformation that batches node starts:

We’re using .strengthL to set the value of the Waiting state, with .pure

again letting us avoid sending an instruction in this code branch.

We .foldMap twice because of the state, and combine the stubs again with

.or:

Then we run the program and assert: that there are no nodes in the Waiting

list, no node has been launched using the old API, and all nodes have been

launched in one call to the batch API.

Congratulations, we’ve saved the company $50 every month, and it only cost a million dollars. But that was some other team’s budget, so it is OK.

We could have done the same monkey patch by hard coding the batching logic into

our algebra implementations. In the defence of Free, we have decoupled the

patch from the implementation, which means we can test it more thoroughly.

7.5.2 FreeAp (Applicative)

Despite this chapter being called Advanced Monads, the takeaway is: don’t use

monads unless you really really have to. In this section, we will see why

FreeAp (free applicative) is preferable to Free monads.

FreeAp is defined as the data structure representation of the ap and pure

methods from the Applicative typeclass:

The methods .hoist and .foldMap are like their Free analogues

.mapSuspension and .foldMap.

As a convenience, we can generate a Free[S, A] from our FreeAp[S, A] with

.monadic. This is especially useful to optimise smaller Applicative

subsystems yet use them as part of a larger Free program.

Like Free, we must create a FreeAp for our ASTs, more boilerplate…

7.5.2.1 Batching Network Calls

We opened this chapter with grand claims about performance. Time to deliver.

Philip Stark’s Humanised version of Peter Norvig’s Latency Numbers serve as motivation for why we should focus on reducing network calls to optimise an application:

| Computer | Human Timescale | Human Analogy |

|---|---|---|

| L1 cache reference | 0.5 secs | One heart beat |

| Branch mispredict | 5 secs | Yawn |

| L2 cache reference | 7 secs | Long yawn |

| Mutex lock/unlock | 25 secs | Making a cup of tea |

| Main memory reference | 100 secs | Brushing your teeth |

| Compress 1K bytes with Zippy | 50 min | Scala compiler CI pipeline |

| Send 2K bytes over 1Gbps network | 5.5 hr | Train London to Edinburgh |

| SSD random read | 1.7 days | Weekend |

| Read 1MB sequentially from memory | 2.9 days | Long weekend |

| Round trip within same datacenter | 5.8 days | Long US Vacation |

| Read 1MB sequentially from SSD | 11.6 days | Short EU Holiday |

| Disk seek | 16.5 weeks | Term of university |

| Read 1MB sequentially from disk | 7.8 months | Fully paid maternity in Norway |

| Send packet CA->Netherlands->CA | 4.8 years | Government’s term |

Although Free and FreeAp incur a memory allocation overhead, the equivalent

of 100 seconds in the humanised chart, every time we can turn two sequential

network calls into one batch call, we save nearly 5 years.

When we are in a Applicative context, we can safely optimise our application

without breaking any of the expectations of the original program, and without

cluttering the business logic.

Luckily, our main business logic only requires an Applicative, recall

To begin, we create the lift boilerplate for the Batch algebra

and then we’ll create an instance of DynAgentsModule with FreeAp as the context

In Chapter 6, we studied the Const data type, which allows us to analyse a

program. It should not be surprising that FreeAp.analyze is implemented in

terms of Const:

We provide a natural transformation to record all node starts and .analyze our

program to get all the nodes that need to be started:

The next step is to extend the instruction set from Orig to Extended, which

includes the Batch.Ast and write a FreeAp program that starts all our

gathered nodes in a single network call

We also need to remove all the calls to Machines.Start, which we can do with a natural transformation

Now we have two programs, and need to combine them. Recall the *> syntax for Functor

Putting it all together under a single method:

That’s it! We .optimise every time we call act in our main loop, which is

just a matter of plumbing.

7.5.3 Coyoneda (Functor)

Named after mathematician Nobuo Yoneda, we can freely generate a Functor data

structure for any algebra S[_]

and there is also a contravariant version

The API is somewhat simpler than Free and FreeAp, allowing a natural

transformation with .trans and a .run (taking an actual Functor or

Contravariant, respectively) to escape the free structure.

Coyo and cocoyo can be a useful utility if we want to .map or .contramap

over a type, and we know that we can convert into a data type that has a Functor

but we don’t want to commit to the final data structure too early. For example,

we create a Coyoneda[ISet, ?] (recall ISet does not have a Functor) to use

methods that require a Functor, then convert into IList later on.

If we want to optimise a program with coyo or cocoyo we have to provide the expected boilerplate for each algebra:

An optimisation we get by using Coyoneda is map fusion (and contramap

fusion), which allows us to rewrite

into

avoiding intermediate representations. For example, if xs is a List of a

thousand elements, we save two thousand object allocations because we only map

over the data structure once.

However it is arguably a lot easier to just make this kind of change in the

original function by hand, or to wait for the better-monadic-for project to

automatically perform these optimisations across our codebase.

7.5.4 Extensible Effects

Programs are just data: free structures help to make this explicit and give us the ability to rearrange and optimise that data.

Free is more special than it appears: it can sequence arbitrary algebras and

typeclasses.

For example, a free structure for MonadState is available. The Ast and

.liftF are more complicated than usual because we have to account for the S

type parameter on MonadState, and the inheritance from Monad:

This gives us the opportunity to use optimised interpreters. For example, we

could store the S in an atomic field instead of building up a nested StateT

trampoline.

We can create an Ast and .liftF for almost any algebra or typeclass! The

only restriction is that the F[_] does not appear as a parameter to any of the

instructions, i.e. it must be possible for the algebra to have an instance of

Functor. This unfortunately rules out MonadError and Monoid.

As the AST of a free program grows, performance degrades because the interpreter

must match over instruction sets with an O(n) cost. An alternative to

scalaz.Coproduct is iotaz’s encoding, which uses an optimised data structure

to perform O(1) dynamic dispatch (using integers that are assigned to each

coproduct at compiletime).

For historical reasons a free AST for an algebra or typeclass is called Initial

Encoding, and a direct implementation (e.g. with IO) is called Finally

Tagless. Although we have explored interesting ideas with Free, it is

generally accepted that finally tagless is superior. But to use finally tagless

style, we need a high performance effect type that provides all the monad

typeclasses we’ve covered in this chapter. We also still need to be able to run

our Applicative code in parallel. This is exactly what we will cover next.

7.6 Parallel

There are two effectful operations that we almost always want to run in parallel:

-

.mapover a collection of effects, returning a single effect. This is achieved by.traverse, which delegates to the effect’s.apply2. - running a fixed number of effects with the scream operator

|@|, and combining their output, again delegating to.apply2.

However, in practice, neither of these operations execute in parallel by

default. The reason is that if our F[_] is implemented by a Monad, then the

derived combinator laws for .apply2 must be satisfied, which say

In other words, Monad is explicitly forbidden from running effects in

parallel.

However, if we have an F[_] that is not monadic, then it may implement

.apply2 in parallel. We can use the @@ (tag) mechanism to create an instance

of Applicative for F[_] @@ Parallel, which is conveniently assigned to the

type alias Applicative.Par

Monadic programs can then request an implicit Par in addition to their Monad

Scalaz’s Traverse syntax supports parallelism:

If the implicit Applicative.Par[IO] is in scope, we can choose between

sequential and parallel traversal:

Similarly, we can call .parApply or .parTupled after using scream operators

It is worth nothing that when we have Applicative programs, such as

we can use F[A] @@ Parallel as our program’s context and get parallelism as

the default on .traverse and |@|. Converting between the raw and @@

Parallel versions of F[_] must be handled manually in the glue code, which

can be painful. Therefore it is often easier to simply request both forms of

Applicative

7.6.1 Breaking the Law

We can take a more daring approach to parallelism: opt-out of the law that

.apply2 must be sequential for Monad. This is highly controversial, but

works well for the majority of real world applications. we must first audit our

codebase (including third party dependencies) to ensure that nothing is making

use of the .apply2 implied law.

We wrap IO

and provide our own implementation of Monad which runs .apply2 in parallel

by delegating to a @@ Parallel instance

We can now use MyIO as our application’s context instead of IO, and get

parallelism by default.

For completeness: a naive and inefficient implementation of Applicative.Par

for our toy IO could use Future:

and due to a bug in the scala compiler that treats all @@ instances as

orphans, we must explicitly import the implicit:

In the final section of this chapter we will see how scalaz’s IO is actually

implemented.

7.7 IO

Scalaz’s IO is the fastest asynchronous programming construct in the Scala

ecosystem: up to 50 times faster than Future and 20% faster than Monix.

IO is a free data structure specialised for use as a general effect monad.

IO has two type parameters: it has a Bifunctor allowing the error type to

be an application specific ADT. But because we are on the JVM, and must interact

with legacy libraries, a convenient type alias is provided that uses exceptions

for the error type:

7.7.1 Creating

There are multiple ways to create an IO that cover a variety of eager, lazy,

safe and unsafe code blocks:

with convenient Task constructors:

The most common constructors, by far, when dealing with legacy code are

Task.apply and Task.fromFuture:

We can’t pass around raw Future, because it eagerly evaluates, so must always

be constructed inside a safe block.

Note that the ExecutionContext is not implicit, contrary to the

convention. Recall that in scalaz we reserve the implicit keyword for

typeclass derivation, to simplify the language: ExecutionContext is

configuration that must be provided explicitly.

7.7.2 Running

The IO interpreter is called RTS, for runtime system. Its implementation

is beyond the scope of this book. We will instead focus on the features that

IO provides.

IO is just a data structure, and is interpreted at the end of the world by

extending SafeApp and implementing .run

If we are integrating with a legacy system and are not in control of the entry

point of our application, we can extend the RTS and gain access to unsafe

methods to evaluate the IO at the entry point to our principled FP code.

For example, if we have an algebra that canonicalises values, and may hit disk or network to resolve filenames and URLs:

we can write a scalatest that extends RTS and call unsafePerformIO to

interpret the IO

7.7.3 Features

IO provides typeclass instances for Bifunctor, MonadError[E, ?],

BindRec, Plus, MonadPlus (if E forms a Monoid), and an

Applicative[IO.Par[E, ?]].

In addition to the functionality from the typeclasses, there are implementation specific methods:

It is possible for an IO to be in a terminated state, which represents work

that is intended to be discarded (it is neither an error nor a success). The

utilities related to termination are:

7.7.4 Fiber

An IO may spawn fibers, a lightweight abstraction over a JVM Thread. We

can .fork an IO, and .supervise any incomplete fibers to ensure that they

are terminated when the IO action completes

When we have a Fiber we can .join back into the IO, or interrupt the

underlying work.

We can use fibers to achieve a form of optimistic concurrency control. Consider

the case where we have data that we need to analyse, but we also need to

validate it. We can optimistically begin the analysis and cancel the work if the

validation fails, which is performed in parallel.

Another usecase for fibers is when we need to perform a fire and forget action. For example, low priority logging over a network.

7.7.5 Promise

A promise represents an asynchronous variable that can be set exactly once (with

complete or error). An unbounded number of listeners can get the variable.

Promise is not something that we typically use in application code. It is a

building block for high level concurrency frameworks.

7.7.6 IORef

IORef is the IO equivalent of an atomic mutable variable.

We can read the variable and we have a variety of ways to write or update it.

IORef is another building block and can be used to provide a high performance

MonadState. For example, create a newtype specialised to Task

We can make use of this optimised StateMonad implementation in a SafeApp,

where our .program depends on optimised MTL typeclasses:

A more realistic application would take a variety of algebras and typeclasses as input.

7.7.6.1 MonadIO

The MonadIO that we previously studied was simplified to hide the E

parameter. The actual typeclass is

with a minor change to the boilerplate on the companion of our algebra,

accounting for the extra E:

7.8 Summary

- The

Futureis broke, don’t go there. - Manage stack safety with a

Trampoline. - The Monad Transformer Library (MTL) abstracts over common effects.

- Monad Transformers provide default implementations of the MTL.

-

Freedata structures let us analyse, optimise and easily test our programs. -

IOgives us the ability to implement algebras as effects on the outside world and interact with legacy systems. -

IOcan perform effects in parallel and provides a high performance implementation of the MTL.