6. Scalaz Data Types

Who doesn’t love a good data structure? The answer is nobody, because data structures are awesome.

In this chapter we’ll explore the collection-like data types in scalaz, as well as data types that augment the Scala language with useful semantics and additional type safety.

The primary reason we care about having lots of collections at our disposal is performance. A vector and a list can do the same things, but their performance characteristics are different: a vector has constant lookup cost whereas a list must be traversed.

All of the collections presented here are persistent: if we add or remove an element we can still use the old version. Structural sharing is essential to the performance of persistent data structures, otherwise the entire collection is rebuilt with every operation.

Unlike the Java and Scala collections, there is no hierarchy to the data types in scalaz: these collections are much simpler to understand. Polymorphic functionality is provided by optimised instances of the typeclasses we studied in the previous chapter. This makes it a lot easier to swap implementations for performance reasons, and to provide our own.

6.1 Type Variance

Many of scalaz’s data types are invariant in their type parameters.

For example, IList[A] is not a subtype of IList[B] when A <:

B.

6.1.1 Covariance

The problem with covariant type parameters, such as class

List[+A], is that List[A] is a subtype of List[Any] and it is

easy to accidentally lose type information.

Note that the second list is a List[Char] and the compiler has

unhelpfully inferred the Least Upper Bound (LUB) to be Any.

Compare to IList, which requires explicit .widen[Any] to permit

the heinous crime:

Similarly, when the compiler infers a type with Product with

Serializable it is a strong indicator that accidental widening has

occurred due to covariance.

Unfortunately we must be careful when constructing invariant data types because LUB calculations are performed on the parameters:

Another similar problem arises from Scala’s Nothing type, which is a subtype

of all other types, including sealed ADTs, final classes, primitives and

null.

There are no values of type Nothing: functions that take a Nothing as a

parameter cannot be run and functions that return Nothing will never return.

Nothing was introduced as a mechanism to enable covariant type parameters, but

a consequence is that we can write un-runnable code, by accident. Scalaz says we

do not need covariant type parameters which means that we are limiting ourselves

to writing practical code that can be run.

6.1.2 Contrarivariance

On the other hand, contravariant type parameters, such as trait

Thing[-A], can expose devastating bugs in the compiler. Consider Paul

Phillips’ (ex-scalac team) demonstration of what he calls

contrarivariance:

As expected, the compiler is finding the most specific argument in

each call to f. However, implicit resolution gives unexpected

results:

Implicit resolution flips its definition of “most specific” for contravariant types, rendering them useless for typeclasses or anything that requires polymorphic functionality.

6.1.3 Limitations of subtyping

scala.Option has a method .flatten which will convert

Option[Option[B]] into an Option[B]. However, Scala’s type system

is unable to let us write the required type signature. Consider the

following that appears correct, but has a subtle bug:

The A introduced on .flatten is shadowing the A introduced on

the class. It is equivalent to writing

which is not the constraint we want.

To workaround this limitation, Scala defines infix classes <:< and

=:= along with implicit evidence that always creates a witness

=:= can be used to require that two type parameters are exactly the

same and <:< is used to describe subtype relationships, letting us

implement .flatten as

Scalaz improves on <:< and =:= with Liskov (aliased to <~<)

and Leibniz (===).

Other than generally useful methods and implicit conversions, the

scalaz <~< and === evidence is more principled than in the stdlib.

6.2 Evaluation

Java is a strict evaluation language: all the parameters to a method

must be evaluated to a value before the method is called. Scala

introduces the notion of by-name parameters on methods with a: =>A

syntax. These parameters are wrapped up as a zero argument function

which is called every time the a is referenced. We seen by-name a

lot in the typeclasses.

Scala also has by-need evaluation of values, with the lazy

keyword: the computation is evaluated at most once to produce the

value. Unfortunately, scala does not support by-need evaluation of

method parameters.

Scalaz formalises the three evaluation strategies with an ADT

The weakest form of evaluation is Name, giving no computational

guarantees. Next is Need, guaranteeing at most once evaluation,

whereas Value is pre-computed and therefore exactly once

evaluation.

If we wanted to be super-pedantic we could go back to all the

typeclasses and make their methods take Name, Need or Value

parameters. Instead we can assume that normal parameters can always be

wrapped in a Value, and by-name parameters can be wrapped with

Name.

When we write pure programs, we are free to replace any Name with

Need or Value, and vice versa, with no change to the correctness

of the program. This is the essence of referential transparency: the

ability to replace a computation by its value, or a value by its

computation.

In functional programming we almost always want Value or Need

(also known as strict and lazy): there is little value in Name.

Because there is no language level support for lazy method parameters,

methods typically ask for a by-name parameter and then convert it

into a Need internally, getting a boost to performance.

Name provides instances of the following typeclasses

MonadComonadDistributiveTraverse1Align-

Zip/Unzip/Cozip

6.3 Memoisation

Scalaz has the capability to memoise functions, formalised by Memo,

which doesn’t make any guarantees about evaluation because of the

diversity of implementations:

memo allows us to create custom implementations of Memo, nilMemo

doesn’t memoise, evaluating the function normally. The remaining

implementations intercept calls to the function and cache results

backed by stdlib collection implementations.

To use Memo we simply wrap a function with a Memo implementation

and then call the memoised function:

If the function takes more than one parameter, we must tupled the

method, with the memoised version taking a tuple.

Memo is typically treated as a special construct and the usual rule

about purity is relaxed for implementations. To be pure only

requires that our implementations of Memo are referential

transparent in the evaluation of K => V. We may use mutable data and

perform I/O in the implementation of Memo, e.g. with an LRU or

distributed cache, without having to declare an effect in the type

signature. Other functional programming languages have automatic

memoisation managed by their runtime environment and Memo is our way

of extending the JVM to have similar support, unfortunately only on an

opt-in basis.

6.4 Tagging

In the section introducing Monoid we built a Monoid[TradeTemplate] and

realised that scalaz does not do what we wanted with Monoid[Option[A]]. This

is not an oversight of scalaz: often we find that a data type can implement a

fundamental typeclass in multiple valid ways and that the default implementation

doesn’t do what we want, or simply isn’t defined.

Basic examples are Monoid[Boolean] (conjunction && vs disjunction ||) and

Monoid[Int] (multiplication vs addition).

To implement Monoid[TradeTemplate] we found ourselves either breaking

typeclass coherency, or using a different typeclass.

scalaz.Tag is designed to address the multiple typeclass implementation

problem without breaking typeclass coherency.

The definition is quite contorted, but the syntax to use it is very clean. This

is how we trick the compiler into allowing us to define an infix type A @@ T

that is erased to A at runtime:

Some useful tags are provided in the Tags object

First / Last are used to select Monoid instances that pick the first or

last non-zero operand. Multiplication is for numeric multiplication instead of

addition. Disjunction / Conjunction are to select && or ||,

respectively.

In our TradeTemplate, instead of using Option[Currency] we can use

Option[Currency] @@ Tags.Last. Indeed this is so common that we can use the

built-in alias, LastOption

letting us write a much cleaner Monoid[TradeTemplate]

To create a raw value of type LastOption, we apply Tag to an Option. Here

we are calling Tag(None).

In the chapter on typeclass derivation, we’ll go one step further and

automatically derive the monoid.

It is tempting to use Tag to markup data types for some form of validation

(e.g. String @@ PersonName), but this should be avoided because there are no

checks on the content of the runtime value. Tag should only be used for

typeclass selection purposes, and we will dedicate a chapter on type

refinement which is how we can mark up types with arbitrary value-level

constraints.

6.5 Natural Transformations

A function from one type to another is written as A => B in scala, which is

syntax sugar for a Function1[A, B]. Scalaz provides similar syntax sugar F ~>

G for functions over type constructors F[_] to G[_].

These F ~> G are called natural transformations and are universally

quantified because they don’t care about the contents of F[_].

An example of a natural transformation is a function that converts an IList

into a List

Or, more concisely, making use of kind-projector’s syntax sugar:

However, in day-to-day development, it is far more likely that we will use a

natural transformation to map between algebras. For example, in

drone-dynamic-agents we may want to implement our Google Container Engine

Machines algebra with an off-the-shelf algebra, BigMachines. Instead of

changing all our business logic and tests to use this new BigMachines

interface, we may be able to write a transformation from Machines ~>

BigMachines. We will return to this idea in the chapter on Advanced Monads.

There is also a natural transformation for type constructors with two type holes:

6.6 Isomorphism

Sometimes we have two types that are really the same thing, causing compatibility problems because the compiler doesn’t know what we know. This typically happens when we use third party code that is the same as something we already have.

This is when Isomorphism can help us out. An isomorphism defines a formal “is

equivalent to” relationship between two types. There are three variants, to

account for types of different shapes:

The type aliases IsoSet, IsoFunctor and IsoBifunctor cover the common

cases: a regular function, natural transformation and binatural. Convenience

functions allow us to generate instances from existing functions or natural

transformations. However, it is often easier to use one of the abstract

Template classes to define an isomorphism. For example:

If we introduce an isomorphism, we can generate many of the standard typeclasses. For example

allows us to derive a Semigroup[F] for a type F if we have an F <=> G and

a Semigroup[G]. Almost all the typeclasses in the hierarchy provide an

isomorphic variant. If we find ourselves copying and pasting a typeclass

implementation, it is worth considering if Isomorphism is the better solution.

6.7 Containers

6.7.1 Maybe

We have already encountered scalaz’s improvement over scala.Option,

called Maybe. It is an improvement because it does not have any

unsafe methods like Option.get, which can throw an exception, and is

invariant.

It is typically used to represent when a thing may be present or not without giving any extra context as to why it may be missing.

The .empty and .just companion methods are preferred to creating

raw Empty or Just instances because they return a Maybe, helping

with type inference. This pattern is often referred to as returning a

sum type, which is when we have multiple implementations of a

sealed trait but never use a specific subtype in a method signature.

A convenient implicit class allows us to call .just on any value

and receive a Maybe

Maybe has a typeclass instance for all the things

AlignTraverse-

MonadPlus/IsEmpty Cobind-

Cozip/Zip/Unzip Optional

and delegate instances depending on A

-

Monoid/Band/SemiLattice -

Equal/Order/Show

In addition to the above, Maybe has some niche functionality that is

not supported by a polymorphic typeclass.

.cata is a terser alternative to .map(f).getOrElse(b) and has the

simpler form | if the map is identity (i.e. just .getOrElse).

.toLeft and .toRight, and their symbolic aliases, create a disjunction

(explained in the next section) by taking a fallback for the Empty case.

.orZero (having ~foo syntax) takes a Monoid to define the

default value.

.orEmpty uses an ApplicativePlus to create a single element or

empty container, not forgetting that we already get support for stdlib

collections from the Foldable instance’s .to method.

6.7.2 Either

Scalaz’s improvement over scala.Either is symbolic, but it is common

to speak about it as either or Disjunction

with corresponding syntax

allowing for easy construction of values. Note that the extension

method takes the type of the other side. So if we wish to create a

String \/ Int and we have an Int, we must pass String when

calling .right

The symbolic nature of \/ makes it read well in type signatures when

shown infix. Note that symbolic types in Scala associate from the left

and nested \/ must have parentheses, e.g. (A \/ (B \/ (C \/ D)).

\/ has right-biased (i.e. flatMap applies to \/-) typeclass

instances for:

-

Monad/MonadError -

Traverse/Bitraverse PlusOptionalCozip

and depending on the contents

-

Equal/Order -

Semigroup/Monoid/Band

In addition, there are custom methods

.fold is similar to Maybe.cata and requires that both the left and

right sides are mapped to the same type.

.swap (and the ~foo syntax) swaps a left into a right and a right

into a left.

The | alias to getOrElse appears similarly to Maybe. We also get

||| as an alias to orElse.

+++ is for combining disjunctions with lefts taking preference over

right:

-

right(v1) +++ right(v2)givesright(v1 |+| v2) -

right(v1) +++ left (v2)givesleft (v2) -

left (v1) +++ right(v2)givesleft (v1) -

left (v1) +++ left (v2)givesleft (v1 |+| v2)

.toEither is provided for backwards compatibility with the Scala

stdlib.

The combination of :?>> and <<?: allow for a convenient syntax to

ignore the contents of an \/, but pick a default based on its type

Scalaz also comes with Either3, for storing one of three values

However, it is common to use nested disjunctions A \/ (B \/ C), making

Either3 redundant.

6.7.3 Validation

At first sight, Validation (aliased with \?/, happy Elvis)

appears to be a clone of Disjunction:

With convenient syntax

However, the data structure itself is not the complete story.

Validation intentionally does not have an instance of any Monad,

restricting itself to success-biased versions of:

Applicative-

Traverse/Bitraverse CozipPlusOptional

and depending on the contents

-

Equal/Order Show-

Semigroup/Monoid

The big advantage of restricting to Applicative is that Validation

is explicitly for situations where we wish to report all failures,

whereas Disjunction is used to stop at the first failure. To

accommodate failure accumulation, a popular form of Validation is

ValidationNel, having a NonEmptyList[E] in the failure position.

Consider performing input validation of data provided by a user using

Disjunction and flatMap:

If we use |@| syntax

we still get back the first failure. This is because Disjunction is

a Monad, its .applyX methods must be consistent with .flatMap

and not assume that any operations can be performed out of order.

Compare to:

This time, we get back all the failures!

Validation has many of the same methods as Disjunction, such as

.fold, .swap and +++, plus some extra:

.append (aliased by +|+) has the same type signature as +++ but

prefers the success case

-

failure(v1) +|+ failure(v2)givesfailure(v1 |+| v2) -

failure(v1) +|+ success(v2)givessuccess(v2) -

success(v1) +|+ failure(v2)givessuccess(v1) -

success(v1) +|+ success(v2)givessuccess(v1 |+| v2)

.disjunction converts a Validated[A, B] into an A \/ B.

Disjunction has the mirror .validation and .validationNel to

convert into Validation, allowing for easy conversion between

sequential and parallel failure accumulation.

\/ and Validation are the more performant FP equivalent of a checked

exception for input validation, avoiding both a stacktrace and requiring the

caller to deal with the failure resulting in more robust systems.

6.7.4 These

We encountered These, a data encoding of inclusive logical OR,

when we learnt about Align. Let’s take a closer look:

with convenient construction syntax

Annoyingly, this is a keyword in Scala and must be called with

back-ticks, or as .wrapThis.

These has typeclass instances for

MonadBitraverseTraverseCobind

and depending on contents

-

Semigroup/Monoid/Band -

Equal/Order Show

These (\&/) has many of the methods we have come to expect of

Disjunction (\/) and Validation (\?/)

.append has 9 possible arrangements and data is never thrown away

because cases of This and That can always be converted into a

Both.

.flatMap is right-biased (Both and That), taking a Semigroup

of the left content (This) to combine rather than break early. &&&

is a convenient way of binding over two of these, creating a tuple

on the right and dropping data if it is not present in each of

these.

Although it is tempting to use \&/ in return types, overuse is an

anti-pattern. The main reason to use \&/ is to combine or split

potentially infinite streams of data in finite memory. Convenient

functions exist on the companion to deal with EphemeralStream

(aliased here to fit in a single line) or anything with a MonadPlus

6.7.5 Higher Kinded Either

The Coproduct data type (not to be confused with the more general concept of a

coproduct in an ADT) wraps Disjunction for type constructors:

Typeclass instances simply delegate to those of the F[_] and G[_].

The most popular use case for Coproduct is when we want to create an anonymous

coproduct for a GADT.

6.7.6 Not So Eager

Built-in Scala tuples, and basic data types like Maybe and

Disjunction are eagerly-evaluated value types.

For convenience, by-name alternatives to Name are provided, having

the expected typeclass instances:

The astute reader will note that Lazy* is a misnomer, and these data

types should perhaps be: ByNameTupleX, ByNameOption and

ByNameEither.

6.7.7 Const

Const, for constant, is a wrapper for a value of type A, along with a

spare type parameter B.

Const provides an instance of Applicative[Const[A, ?]] if there is a

Monoid[A] available:

The most important thing about this Applicative is that it ignores the B

parameters, continuing on without failing and only combining the constant values

that it encounters.

Going back to our example application drone-dynamic-agents, we should first

refactor our logic.scala file to use Applicative instead of Monad. We

wrote logic.scala before we learnt about Applicative and now we know better:

Since our business logic only requires an Applicative, we can write mock

implementations with F[a] as Const[String, a]. In each case, we return the

name of the function that is called:

With this interpretation of our program, we can assert on the methods that are called:

Alternatively, we could have counted total method calls by using Const[Int, ?]

or an IMap[String, Int].

With this test, we’ve gone beyond traditional Mock testing with a Const test

that asserts on what is called without having to provide implementations. This

is useful if our specification demands that we make certain calls for certain

input, e.g. for accounting purposes. Furthermore, we’ve achieved this with

compiletime safety.

Let’s take this line of thinking a little further and say we want to monitor (in

production) the nodes that we are stopping in act. We can create

implementations of Drone and Machines with Const, calling it from our

wrapped version of act

We can do this because monitor is pure and running it produces no side

effects.

This runs the program with ConstImpl, extracting all the calls to

Machines.stop, then returning it alongside the WorldView. We can unit test

this:

We have used Const to do something that looks like Aspect Oriented

Programming, once popular in Java. We built on top of our business logic to

support a monitoring concern, without having to complicate the business logic.

It gets even better. We can run ConstImpl in production to gather what we want

to stop, and then provide an optimised implementation of act that can make

use of implementation-specific batched calls.

The silent hero of this story is Applicative. Const lets us show off what is

possible. If we need to change our program to require a Monad, we can no

longer use Const and must write full mocks to be able to assert on what is

called under certain inputs. The Rule of Least Power demands that we use

Applicative instead of Monad wherever we can.

6.8 Collections

Unlike the stdlib Collections API, the scalaz approach describes collection

behaviours in the typeclass hierarchy, e.g. Foldable, Traverse, Monoid.

What remains to be studied are the implementations in terms of data structures,

which have different performance characteristics and niche methods.

Because all the collection data types provide more or less the same list of typeclass instances, we shall avoid repeating the list, which is often some variation of:

Monoid-

Traverse/Foldable -

MonadPlus/IsEmpty -

Cobind/Comonad -

Zip/Unzip Align-

Equal/Order Show

Data structures that are provably non-empty are able to provide

-

Traverse1/Foldable1

and provide Semigroup instead of Monoid, Plus instead of IsEmpty.

6.8.1 Lists

We have used IList[A] and NonEmptyList[A] so many times by now that they

should be familiar. They codify a classic linked list data structure:

The main advantage of IList over stdlib List is that there are no

unsafe methods, like .head which throws an exception on an empty

list.

In addition, IList is a lot simpler, having no hierarchy and a

much smaller bytecode footprint. Furthermore, the stdlib List has a

terrifying implementation that uses var to workaround performance

problems in the stdlib collection design:

List creation requires careful, and slow, Thread synchronisation

to ensure safe publishing. IList requires no such hacks and can

therefore outperform List.

6.8.2 EphemeralStream

The stdlib Stream is a lazy version of List, but is riddled with

memory leaks and unsafe methods. EphemeralStream does not keep

references to computed values, helping to alleviate the memory

retention problem, and removing unsafe methods in the same spirit as

IList.

.cons, .unfold and .iterate are mechanisms for creating streams, and the

convenient syntax ##:: puts a new element at the head of a by-name EStream

reference. .unfold is for creating a finite (but possibly infinite) stream by

repeatedly applying a function f to get the next value and input for the

following f. .iterate creates an infinite stream by repeating a function f

on the previous element.

EStream may appear in pattern matches with the symbol ##::,

matching the syntax for .cons.

Although EStream addresses the value memory retention problem, it is

still possible to suffer from slow memory leaks if a live reference

points to the head of an infinite stream. Problems of this nature, as

well as the need to compose effectful streams, are why fs2 exists.

6.8.3 CorecursiveList

Corecursion is when we start from a base state and produce subsequent steps

deterministically, like the EphemeralStream.unfold method that we just

studied:

Contrast to recursion, which breaks data into a base state and then terminates.

A CorecursiveList is a data encoding of EphemeralStream.unfold, offering an

alternative to EStream that may perform better in some circumstances:

Corecursion is useful when implementing Comonad.cojoin, like our Hood

example. CorecursiveList is a good way to codify non-linear recurrence

equations like those used in biology population models, drone control systems,

macro economics, and investment banking models.

6.8.4 ImmutableArray

A simple wrapper around mutable stdlib Array, with primitive

specialisations:

Array is unrivalled in terms of read performance and heap size.

However, there is zero structural sharing when creating new arrays,

therefore arrays are typically used only when their contents are not

expected to change, or as a way of safely wrapping raw data from a

legacy system.

6.8.5 Dequeue

A Dequeue (pronounced like a “deck” of cards) is a linked list that

allows items to be put onto or retrieved from the front (cons) or

the back (snoc) in constant time. Removing an element from either

end is constant time on average.

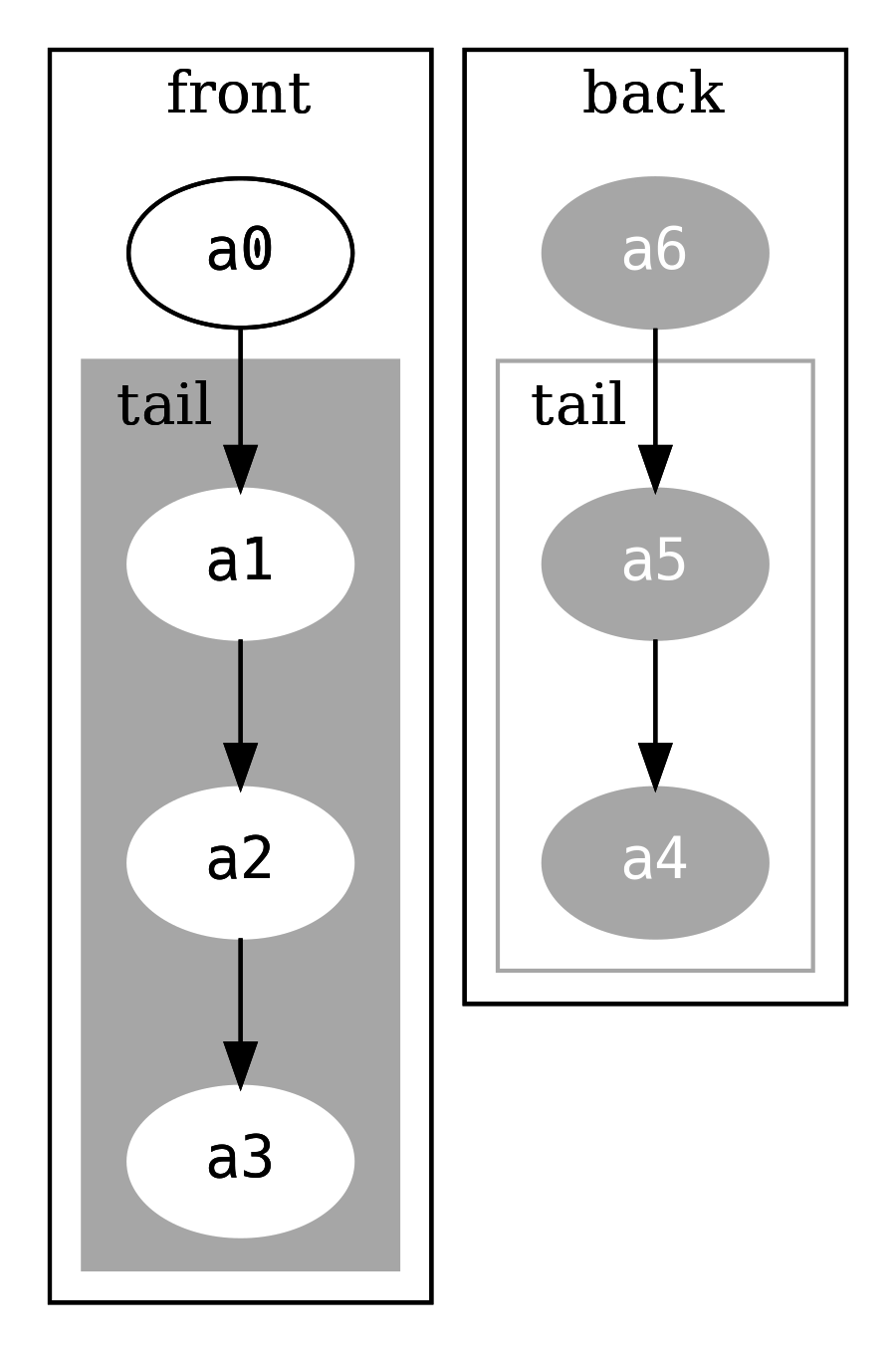

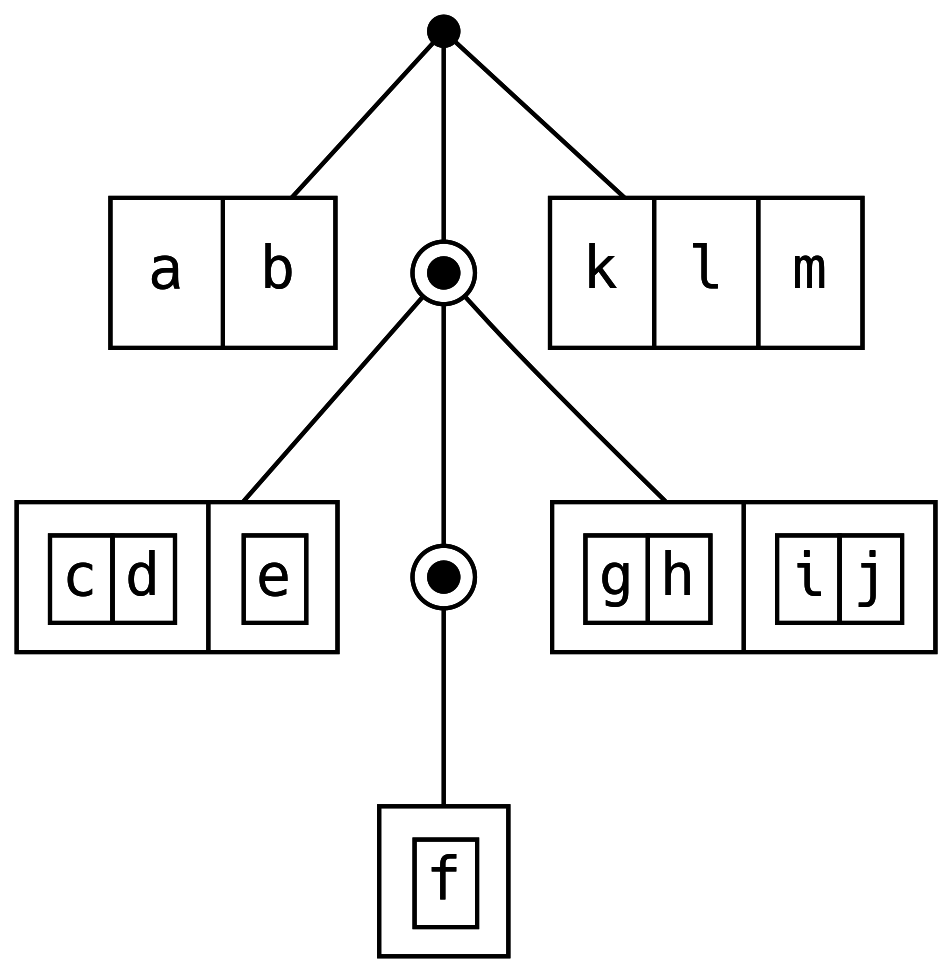

The way it works is that there are two lists, one for the front data

and another for the back. Consider an instance holding symbols a0,

a1, a2, a3, a4, a5, a6

which can be visualised as

Note that the list holding the back is in reverse order.

Reading the snoc (final element) is a simple lookup into

back.head. Adding an element to the end of the Dequeue means

adding a new element to the head of the back, and recreating the

FullDequeue wrapper (which will increase backSize by one). Almost

all of the original structure is shared. Compare to adding a new

element to the end of an IList, which would involve recreating the

entire structure.

The frontSize and backSize are used to re-balance the front and

back so that they are always approximately the same size.

Re-balancing means that some operations can be slower than others

(e.g. when the entire structure must be rebuilt) but because it

happens only occasionally, we can take the average of the cost and say

that it is constant.

6.8.6 DList

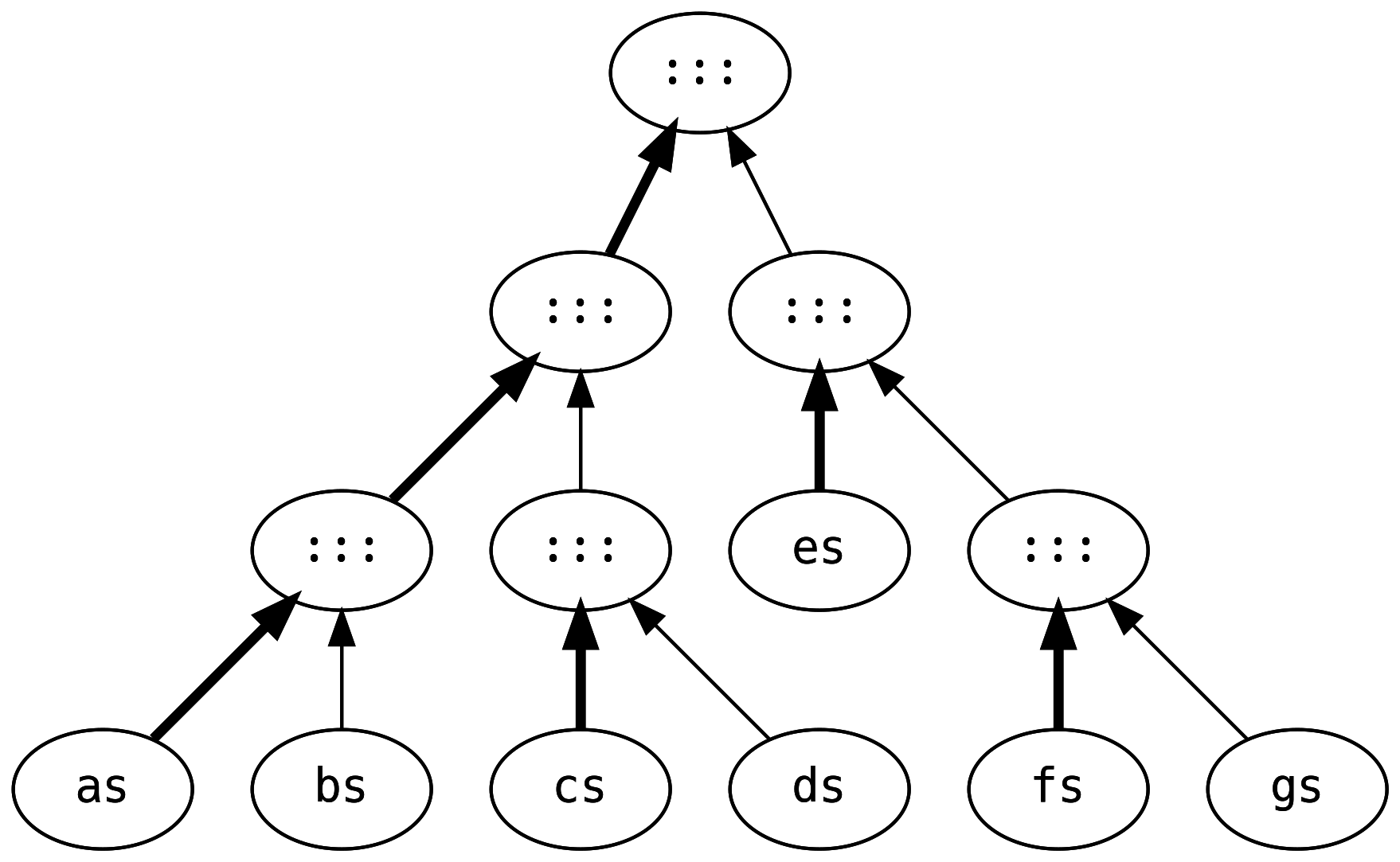

Linked lists have poor performance characteristics when large lists are appended together. Consider the work that goes into evaluating the following:

This creates six intermediate lists, traversing and rebuilding every list three

times (except for gs which is shared between all stages).

The DList (for difference list) is a more efficient solution for this

scenario. Instead of performing the calculations at each stage, it is

represented as a function IList[A] => IList[A]

The equivalent calculation is (the symbols created via DList.fromIList)

which breaks the work into right-associative (i.e. fast) appends

utilising the fast constructor on IList.

As always, there is no free lunch. There is a memory allocation overhead that

can slow down code that naturally results in right-associative appends. The

largest speedup is when IList operations are left-associative, e.g.

Difference lists suffer from bad marketing. If they were called a

ListBuilderFactory they’d probably be in the standard library.

6.8.7 ISet

Tree structures are excellent for storing ordered data, with every binary node holding elements that are less than in one branch, and greater than in the other. However, naive implementations of a tree structure can become unbalanced depending on the insertion order. It is possible to maintain a perfectly balanced tree, but it is incredibly inefficient as every insertion effectively rebuilds the entire tree.

ISet is an implementation of a tree of bounded balance, meaning that it is

approximately balanced, using the size of each branch to balance a node.

ISet requires A to have an Order. The Order[A] instance must remain the

same between calls or internal assumptions will be invalid, leading to data

corruption: i.e. we are assuming typeclass coherence such that Order[A] is

unique for any A.

The ISet ADT unfortunately permits invalid trees. We strive to write ADTs that

fully describe what is and isn’t valid through type restrictions, but sometimes

there are situations where it can only be achieved by the inspired touch of an

immortal. Instead, Tip / Bin are private, to stop users from accidentally

constructing invalid trees. .insert is the only way to build an ISet,

therefore defining what constitutes a valid tree.

The internal methods .balanceL and .balanceR are mirrors of each other, so

we only study .balanceL, which is called when the value we are inserting is

less than the current node. It is also called by the .delete method.

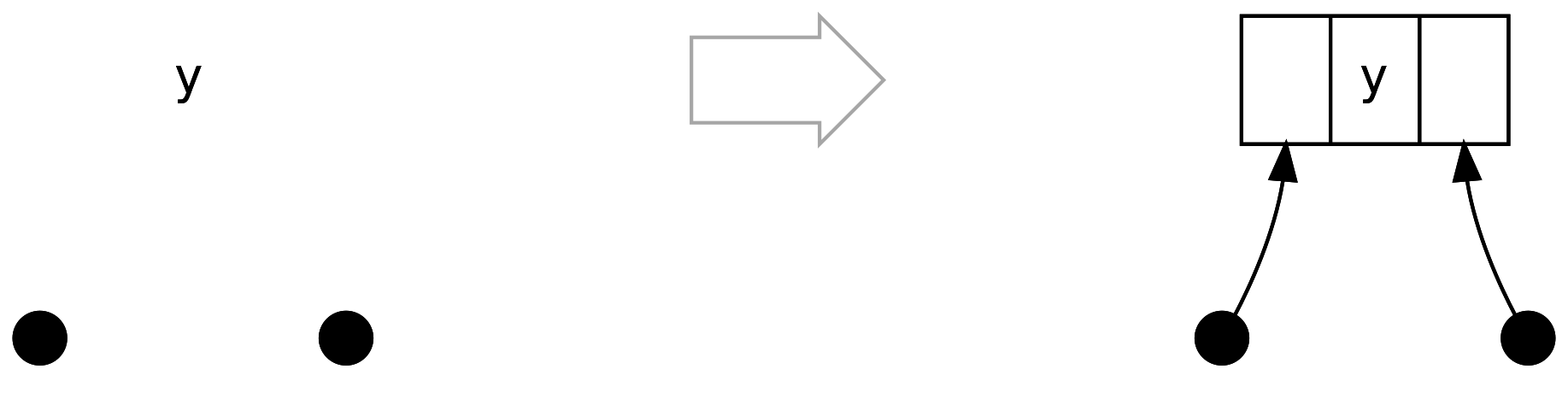

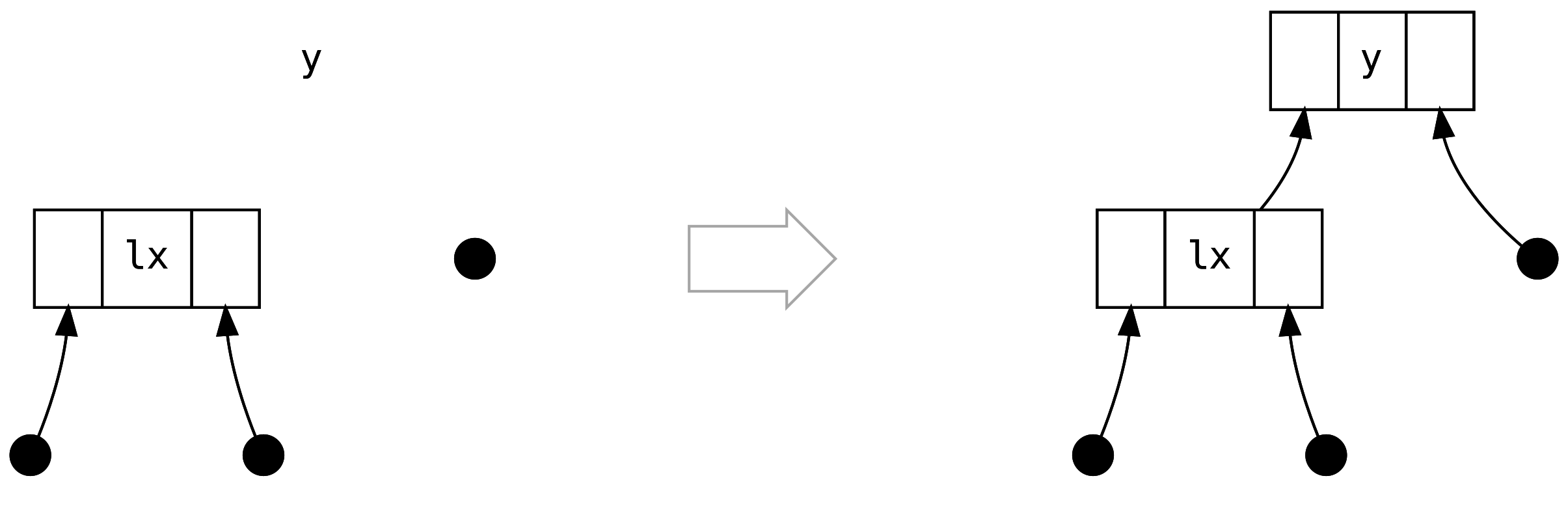

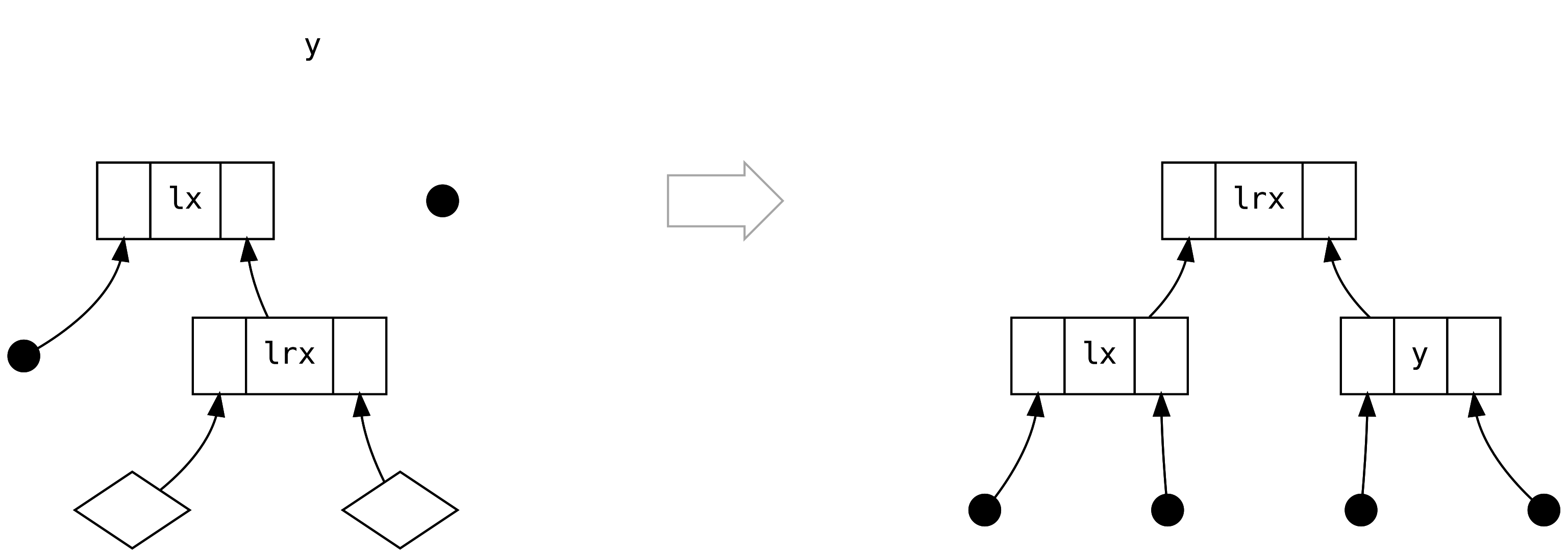

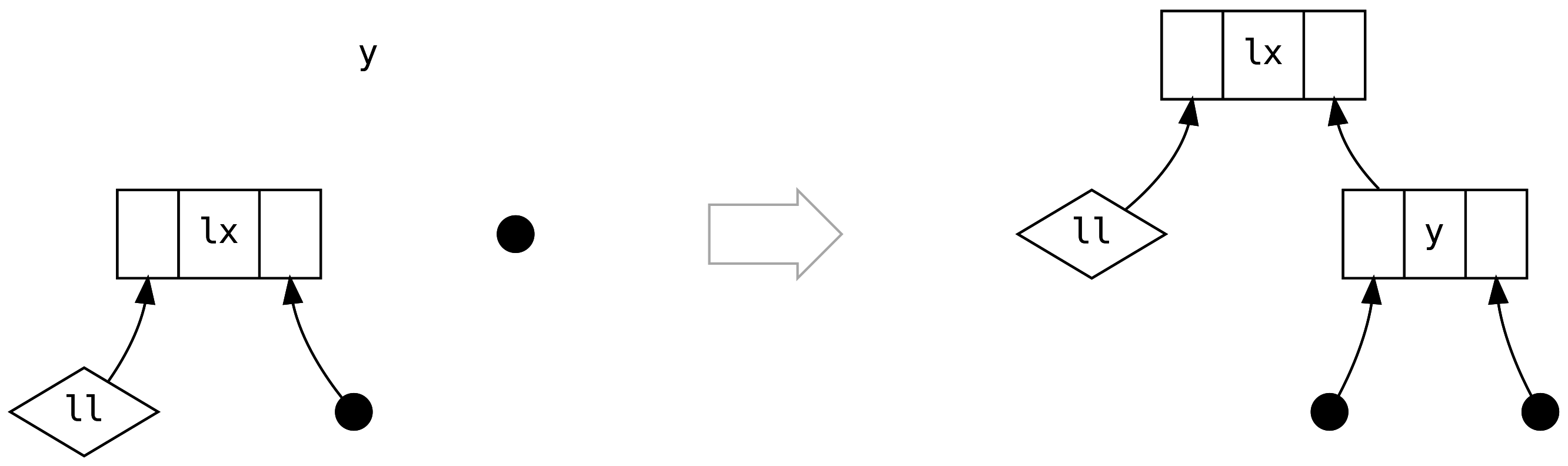

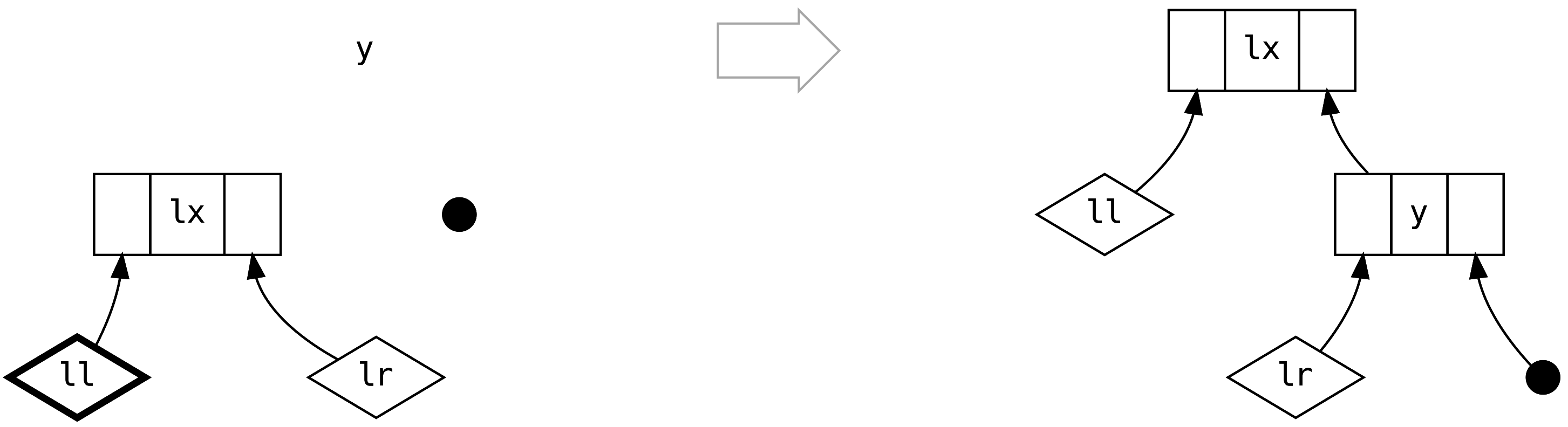

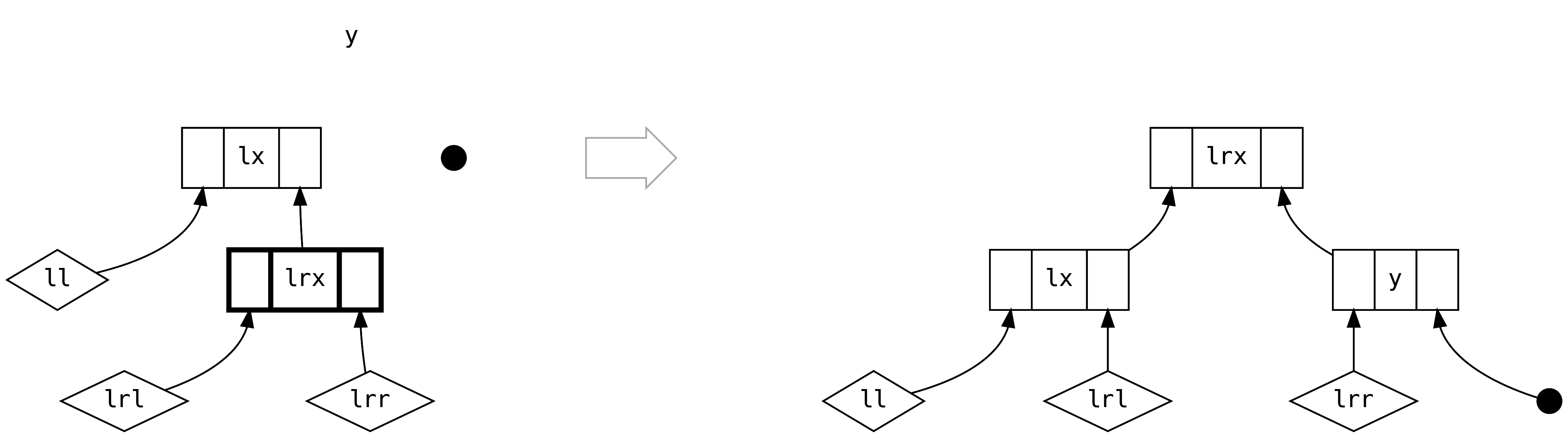

Balancing requires us to classify the scenarios that can occur. We will go

through each possible scenario, visualising the (y, left, right) on the left

side of the page, with the balanced structure on the right, also known as the

rotated tree.

- filled circles visualise a

Tip - three columns visualise the

left | value | rightfields ofBin - diamonds visualise any

ISet

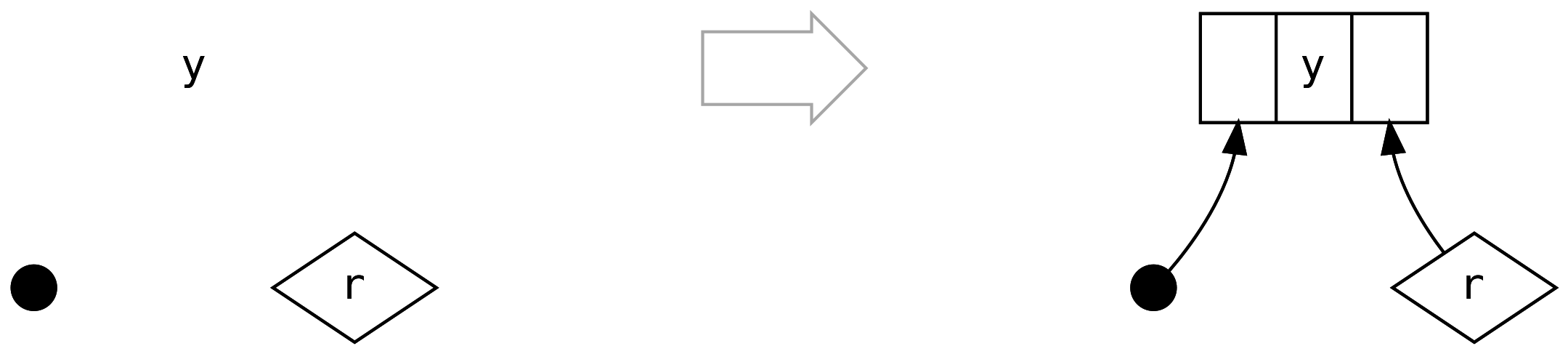

The first scenario is the trivial case, which is when both the left and

right are Tip. In fact we will never encounter this scenario from .insert,

but we hit it in .delete

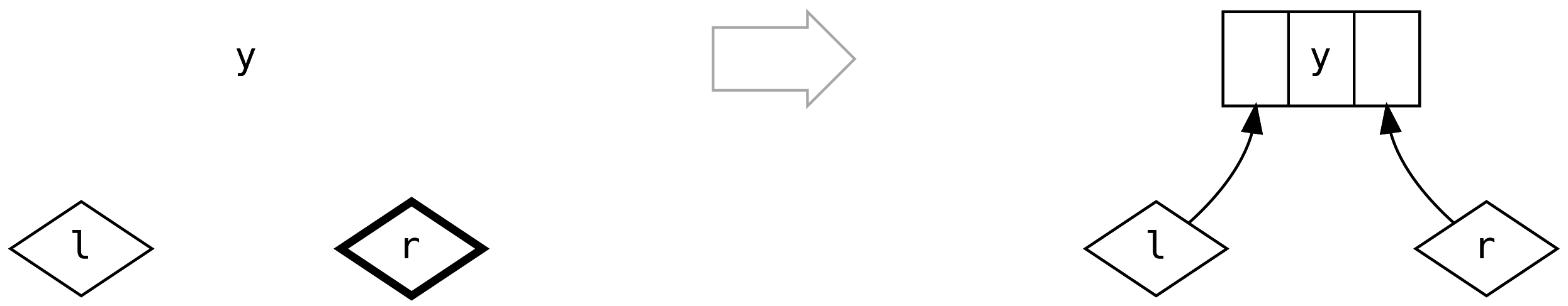

The second case is when left is a Bin containing only Tip, we don’t need

to balance anything, we just create the obvious connection:

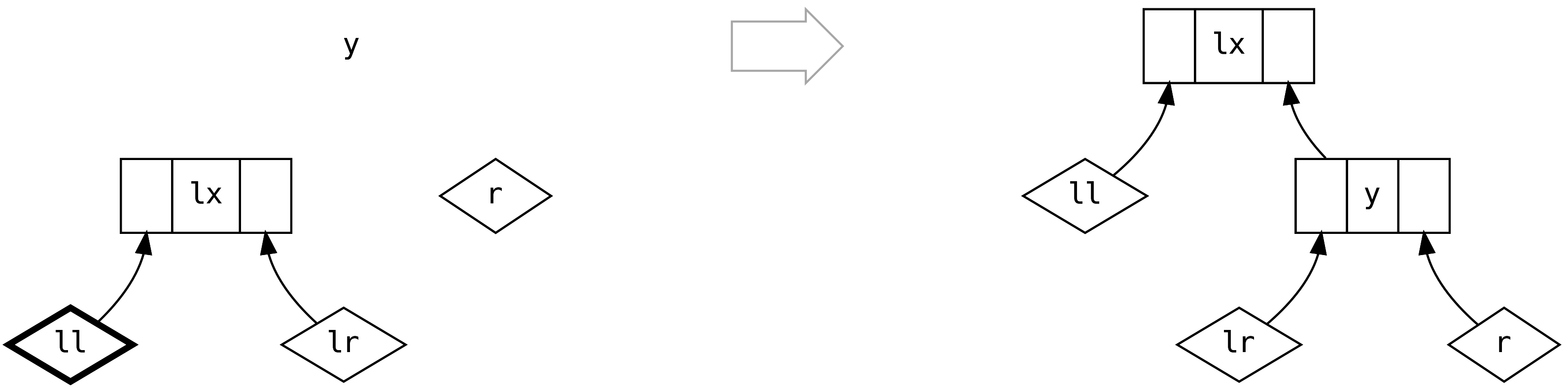

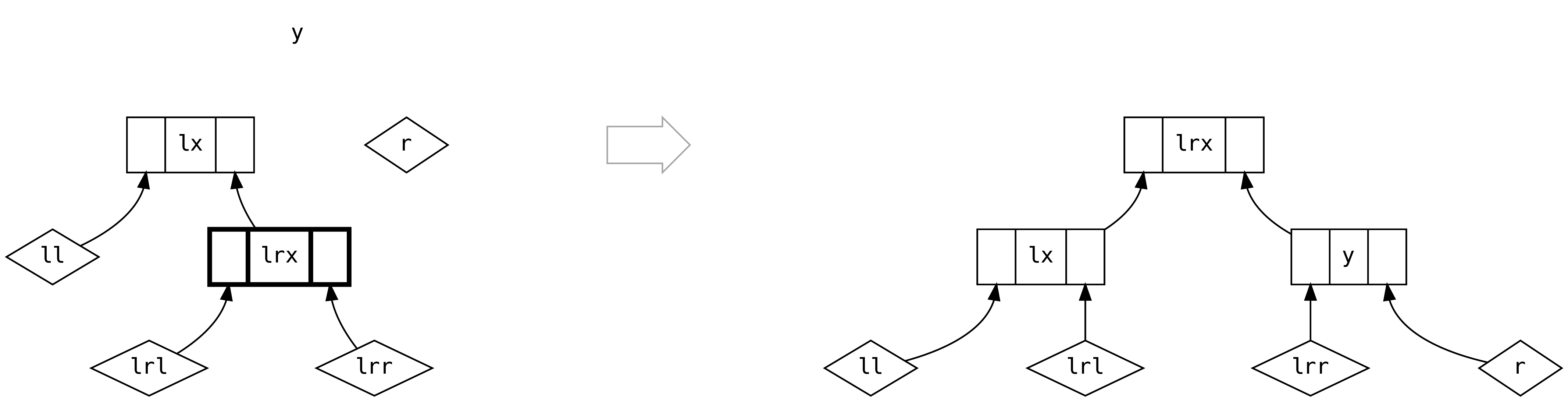

The third case is when it starts to get interesting: left is a Bin

containing a Bin in its right

But what happened to the two diamonds sitting below lrx? Didn’t we just lose

information? No, we didn’t lose information, because we can reason (based on

size balancing) that they are always Tip! There is no rule in any of the

following scenarios (or in .balanceR) that can produce a tree of the shape

where the diamonds are Bin.

The fourth case is the opposite of the third case.

The fifth case is when we have full trees on both sides of the left and we

must use their relative sizes to decide on how to re-balance.

For the first branch, 2*ll.size > lr.size

and for the second branch 2*ll.size <= lr.size

The sixth scenario introduces a tree on the right. When the left is empty we

create the obvious connection. This scenario never arises from .insert because

the left is always non-empty:

The final scenario is when we have non-empty trees on both sides. Unless the

left is three times or more the size of the right, we can do the simple

thing and create a new Bin

However, should the left be more than three times the size of the right, we

must balance based on the relative sizes of ll and lr, like in scenario

five.

This concludes our study of the .insert method and how the ISet is

constructed. It should be of no surprise that Foldable is implemented in terms

of depth-first search along the left or right, as appropriate. Methods such

as .minimum and .maximum are optimal because the data structure already

encodes the ordering.

It is worth noting that some typeclass methods cannot be implemented as

efficiently as we would like. Consider the signature of Foldable.element

The obvious implementation for .element is to defer to (almost) binary-search

ISet.contains. However, it is not possible because .element provides Equal

whereas .contains requires Order.

ISet is unable to provide a Functor for the same reason. In practice this

turns out to be a sensible constraint: performing a .map would involve

rebuilding the entire structure. It is sensible to convert to some other

datatype, such as IList, perform the .map, and convert back. A consequence

is that it is not possible to have Traverse[ISet] or Applicative[ISet].

6.8.8 IMap

This is very familiar! Indeed, IMap (an alias to the lightspeed operator

==>>) is another size-balanced tree, but with an extra value: B field in

each binary branch, allowing it to store key/value pairs. Only the key type A

needs an Order and a suite of convenient methods are provided to allow easy

entry updating

6.8.9 StrictTree and Tree

Both StrictTree and Tree are implementations of a Rose Tree, a tree

structure with an unbounded number of branches in every node (unfortunately

built from standard library collections for legacy reasons):

Tree is a by-need version of StrictTree with convenient constructors

The user of a Rose Tree is expected to manually balance it, which makes it suitable for cases where it is useful to encode domain knowledge of a hierarchy into the data structure. For example, in artificial intelligence, a Rose Tree can be used in clustering algorithms to organise data into a hierarchy of increasingly similar things. It is possible to represent XML documents with a Rose Tree.

If you find yourself working with hierarchical data, consider using a Rose Tree instead of rolling a custom data structure.

6.8.10 FingerTree

Finger trees are generalised sequences with amortised constant cost lookup and

logarithmic concatenation. A is the type of data and it may help to ignore

V:

Visualising FingerTree as dots, Finger as boxes and Node as boxes within

boxes:

Adding elements to the front of a FingerTree with +: is efficient because

Deep simply adds the new element to its left finger. If the finger is a

Four, we rebuild the spine to take 3 of the elements as a Node3. Adding to

the end, :+, is the same but in reverse.

Appending |+| (also <++>) is more efficient than adding one element at a

time because the case of two Deep trees can retain the outer branches,

rebuilding the spine based on the 16 possible combinations of the two Finger

values in the middle.

In the above we skipped over V. Not shown in the ADT description is an

implicit measurer: Reducer[A, V] on every element of the ADT.

Reducer is an extension of Monoid that allows for single elements to be

added to an M

For example, Reducer[A, IList[A]] can provide an efficient .cons

6.8.10.1 IndSeq

If we use Int as V, we can get an indexed sequence, where the measure is

size, allowing us to perform index-based lookup by comparing the desired index

with the size at each branch in the structure:

Another use of FingerTree is as an ordered sequence, where the measure stores

the largest value contained by each branch:

6.8.10.2 OrdSeq

OrdSeq has no typeclass instances so it is only useful for incrementally

building up an ordered sequence, with duplicates. We can access the underlying

FingerTree when needed.

6.8.10.3 Cord

The most common use of FingerTree is as an efficient intermediate holder for

String representations in Show. Building a single String can be thousands

of times faster than the default case class implementation of nested

.toString, which builds a String for every layer in the ADT.

For example, the Cord[String] instance returns a Three with the string in

the middle and quotes on either side

Therefore a String renders as it is written in source code

6.8.11 Heap Priority Queue

A priority queue is a data structure that allows fast insertion of ordered elements, allowing duplicates, with fast access to the minimum value (highest priority). The structure is not required to store the non-minimal elements in order. A naive implementation of a priority queue could be

This push is a very fast O(1), but reorder (and therefore pop) relies on

IList.sorted costing O(n log n).

Scalaz encodes a priority queue, with a tree structure where every node has a

value less than its children, called a Heap Priority Queue. Heap has fast

push (insert), union, size, pop (uncons) and peek (minimumO)

operations:

Heap is implemented with a Rose Tree of Ranked values, where the rank is

the depth of a subtree, allowing us to depth-balance the tree. We manually

maintain the tree so the minimum value is at the top. An advantage of encoding

the minimum value in the data structure is that minimumO (also known as

peek) is a free lookup:

When inserting a new entry, we compare to the current minimum and replace if the new entry is lower:

Insertions of non-minimal values result in an unordered structure in the branches of the minimum. When we encounter two or more subtrees of equal rank, we optimistically put the minimum to the front:

Avoiding a full ordering of the tree makes insert very fast, O(1), such that

producers adding to the queue are not penalised. However, the consumer pays the

cost when calling uncons, with deleteMin costing O(log n) because it must

search for the minimum value, and remove it from the tree by rebuilding. That’s

fast when compared to the naive implementation.

The union operation also delays ordering allowing it to be O(1).

If the Order[Foo] does not correctly capture the priority we want for the

Heap[Foo], we can use Tag and provide a custom Order[Foo @@ Custom] for a

Heap[Foo @@ Custom].

6.8.12 Diev (Discrete Intervals)

We can efficiently encode the (unordered) integer values 6, 9, 2, 13, 8, 14, 10,

7, 5 as inclusive intervals [2, 2], [5, 10], [13, 14]. Diev is an efficient

encoding of intervals for elements A that have an Enum[A], getting more

efficient as the contents become denser.

When updating the Diev, adjacent intervals are merged (and then ordered) such

that there is a unique representation for a given set of values.

A great usecase for Diev is for storing time periods. For example, in our

TradeTemplate from the previous chapter

if we find that the payments are very dense, we may wish to swap to a Diev

representation for performance reasons, without any change in our business logic

because we used Monoid, not any List specific methods. We would, however,

have to provide an Enum[LocalDate], which is an otherwise useful thing to

have.

6.8.13 OneAnd

Recall that Foldable is the scalaz equivalent of a collections API and

Foldable1 is for non-empty collections. So far we have only seen

NonEmptyList to provide a Foldable1. The simple data structure OneAnd

wraps any other collection to turn it into a Foldable1:

NonEmptyList[A] could be an alias to OneAnd[IList, A]. Similarly, we can

create non-empty Stream, DList and Tree structures. However it may break

ordering and uniqueness characteristics of the underlying structure: a

OneAnd[ISet, A] is not a non-empty ISet, it is an ISet with a guaranteed

first element that may also be in the ISet.

6.9 Summary

In this chapter we have skimmed over the data types that scalaz has to offer.

It is not necessary to remember everything in this chapter: think of each section as having planted the kernel of an idea in your mind. If, in a few months, you find yourself thinking “I remember reading about a data structure that might be useful here” and you return to these pages, we have succeeded.

The world of functional data structures is an active area of research. Academic publications appear regularly with new approaches to old problems. If you are the kind of person who would like to contribute back to scalaz, finding a functional data structure to implement would be greatly appreciated.