6: I and We and I

What am I? I am… something… I… whatever ‘I’ is, I suppose. “I think, therefore I am”? Not really: it would be just as true to say “I relate, therefore I am” - and certainly far closer to many people’s experience. “I am a rock, I am an island”? Makes a good song, but it doesn’t work out that way in practice: in fact, it would probably make more sense to say that I’m the sea - part of the sea, in the sea, an expression of the sea as a whole. The sea of wyrd, that is… and in that weird sense, ‘I’ is not that which changes: ‘I’ is that which chooses.

So we can choose to think of ‘I’ - or experience ‘I’ - as a thought, a relating, a rock, an island, an amorphous sea, or anything else: it’s up to us. Each choice of ‘I’ is a thread, a path with many possibilities and an ultimate ending - and many, many interesting twists upon the way…

But if that’s ‘I’, what is ‘We’? If We is what happens between us, between your ‘I’ and mine, then where - if anywhere - is the boundary of We, the boundaries between I and We and I? Weird… wyrd… ‘wyrder’, perhaps?

Which I is We?

“‘I’ is not that which changes: ‘I’ is that which chooses.” Yeah. Sure. If you say so. No problem.

Hey, wait a minute… that’s not right! What about the times when it isn’t my choice to change: like when I have to do what others tell me to do? Or the different things I find myself doing when I’m with other people? Who’s doing the choosing there - because it certainly isn’t me… is it?

We do change in different circumstances, and with different people: our behaviour certainly changes, though whether that’s truly ‘I’ is another matter… The issue is more about choice, about whether we choose to change our surface ‘I’ in response to the changes in our surroundings - and the answer to that question would have to be ‘Sometimes’! Sometimes we do consciously choose to change, to ‘fit in’ with what everyone else seems to be doing - which in itself can cause problems, for us or for others; and sometimes we change more ‘by default’ for much the same reasons, but without really being conscious that we’ve chosen to do so.

Even when we ‘have to’ change our behaviour to suit others - pandering to a bullying boss, perhaps - it is still a choice: there’d be different consequences for choosing to do otherwise, of course, of which we’re no doubt all too aware - but the choice is ours. That’s important, because if we say they’ve ‘made’ us or ‘forced’ us to change our behaviour, we’ve surrendered our power of choice to them. They haven’t ‘taken’ it from us - though no doubt in many cases that’s what they’d want us to believe… A central part of reclaiming our power with others is in becoming more aware that our power to choose our ‘I’ actually resides in us - and nowhere else. The hard part is in taking responsibility for that fact: it always seems much easier to hide from responsibility with that ever-popular excuse, “oh, sorry, I wasn’t myself there…”, or - even more popular - to blame others instead!

The temptation to duck that responsibility is always strongest when there’s a lot of weird energy flying around. ‘Being in love’ (or, as the veteran feminist Glen Tomasetti wryly put it, being caught up in ‘romanticised lust’!) is one obvious obvious example; so too is the bizarre behaviour - and even more bizarre childish language - many people indulge in when they’re around newborn babies! But perhaps the strangest twists in behaviour occur in religious or supposedly ‘spiritual’ settings: in some cases people literally ‘abandon themselves’ to whatever happens to be going on… infamous examples of which include the ritualised murders committed by the original ‘assassins’ - Arabs caught up in an hashish-induced ‘religious experience’ - and ‘thugs’ - devotees of an obscure Indian cult known as ‘thuggee’. I remember one well-known Indian ‘guru’ being very careful to point out that the ‘weird energies’ that his followers experienced around him - and which they inevitably attributed to him - were, strictly speaking, entirely their own: he provided conditions under which people could become aware of their own power - conditions which were as safe and stable as he could provide, which was by no means easy - but he could not and would not take responsibility for what was, he reminded them, their choice of what to do with that power.

‘We’ is the interweaving of ‘I’ and ‘I’ (or, when many people are involved, at least as many ‘I’s as there are people); ‘We’ is a kind of compound-‘I’ created by many people’s choices interweaving and echoing along the threads of wyrd. In the guru’s example, he was being responsible for his own ‘I’, and for its part - his part - in the ‘We’ being created at that gathering: but precious few other people there were doing so… If no-one (or almost no-one) is taking responsibility for their own ‘I’ - as is often the case with any large crowd - then which ‘I’ is ‘We’? Without awareness, and without responsibility, ‘We’ could be anything: often that which is least conscious, and most suppressed and denied - as we can see all too clearly in many large crowds… But we can begin to have choice - and a better awareness of our own choices - by noticing how we change in the company of others: by listening to ‘We’, we gain a better understanding of ‘I’.

Listening to We

‘Listening’ is far more than just hearing what someone says: it’s about being aware of the whole of the communication, and being an involved - and often active - part of that communication. (‘Communication’ itself literally means a ‘one-ness’, an acknowledgement of the interwovenness of each other on the threads of wyrd.) Words themselves can easily go ‘in one ear and out of the other’: it’s the communication as a whole - the words, the tone and pitch of voice, the ‘body language’ and everything else - to which we need to pay attention in listening. The first part of listening to ‘We’, then, is that we need to become more aware of the dance of ‘We’.

In some ways this is easier to notice when there’s only the dance, and nothing else. Even when there’s no verbal component to the communication, there’s still always communication…

Adapting ourselves to others is still a choice; especially, adapting ourselves for the approval of others, or to keep others ‘happy’, is still a choice. And if we’re not aware of the choices we make - if we’ve abandoned our awareness to the ‘senses taker’ of habit, for example - then we have, in effect, lost that choice. If we abandon that choice, we in effect abandon ‘I’ - and then can’t exactly be surprised if we repeatedly find ourselves engulfed in whatever ‘We’ happens to be passing by… So another central part of listening to ‘We’ is learning to listen, very carefully, to ‘I’.

One of the weirder paradoxes of ‘We’ - and one that illustrates well the nature of the wyrd - is that whatever is not being expressed by someone invariably ends up being expressed elsewhere by someone else. It’s as though unexpressed anger, for example, has to come out somewhere: a kind of automatic, unconscious version of what’s known in psychology as ‘projection’, but projected out to the wyrd in general rather than onto a selected individual who can be blamed for it. By becoming aware of what is our choice, if we find ourselves doing or feeling something that is not our choice, then it’s probably coming not from us but from ‘We’, our interaction with others through the wyrd. The computer consultant Gerald Weinberg, borrowing from fellow-consultant Nancy Brown, describes this awareness as ‘listening to the inner music’: when we’re with someone else, and there’s a kind of dischord in the inner music, it’s time to bring it into conscious awareness - and, if appropriate, conscious action.

But this only works when we’re rigorously honest with ourselves about what is our ‘stuff’, and what isn’t… If we’re not, we’ll end up ‘projecting’, onto others, what are actually our feelings that we want to pretend we don’t have: for example, we’ll say that they’re the ones who are angry, not us - because it’s too dangerous for us to admit, even to ourselves, that in reality we’re the ones who are angry. That dishonesty - that self-dishonesty - is where the whole mess starts: it always seems much easier to blame others than to face the responsibility for our own issues ourselves…

This is why the sociologist Hugh Mackay describes true listening not just as an act of generosity, but an act of courage. To be rigorously honest about our own web of beliefs and assumptions - what Mackay calls ‘the cage’ - is embarrassing, disturbing, even frightening, and always real work: as Mackay put it, “if you’re not sensing the strain involved in stepping outside of the cage to listen, then you are probably not listening fully, openly, non-judgementally”.

But if what I’m ‘listening’ out for in myself, in these situations, is actually someone else’s feelings - someone else’s anger, perhaps - then what on earth is ‘We’? If I’m finding myself angry because someone else is, but isn’t admitting it, then where - if anywhere - is the boundary between my ‘I’ and theirs? Weird? Too right it is…

The circles of We

At this point it’s obvious that we need some kind of model or analogy, to clear away some of the muddiness of these confusing experiences! So let’s go back to the beginning, to that analogy of the Möbius loop as a boundary between ‘I’ and ‘not-I’. Because of the twist in that loop, the inside becomes the outside becomes the inside again; there is a definite boundary, and yet at the same time there is no boundary. That’s wyrd…

Let’s hang on that that analogy for a while. First there’s ‘I’, all alone - literally, ‘all-one’ - a single circle, or a single loop:

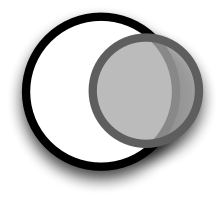

Along comes someone else. From my perspective, that’s another person, a ‘Thou’; but from their perspective, they’re also ‘I’, so now we have two circles, two loops:

And that’s what we’d have if it was true that “I am a rock, I am an island”: two entirely separate ‘I’s, never communicating in any way at all. But we do know, from those weird experiences, that there is always some kind of interweaving or overlap. The threads of wyrd pass through every point; every choice echoes up and down the threads; there is a boundary between ‘I’ and ‘I’, and yet there is no boundary. That area of overlap, we could say, is what we experience as ‘We’: an area where we both experience that we have choices - if we allow ourselves to do so…

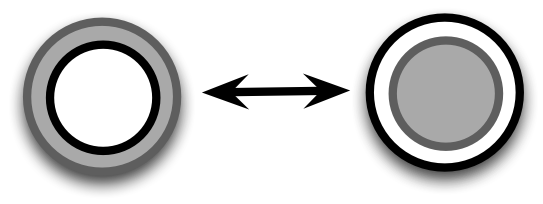

So in the classic concept of dependence, one person has all but abandoned their ‘I’ in favour of what they believe ‘We’ to be:

That ‘included’ space feels protected - for a while… and also apparently in control of the other person, because there’s so much overlap. The assumption is that because the entire focus is on ‘We’, there is only ‘We’ - neither ‘I’ exists, or needs to exist, since each is submerged into the sea of ‘We’. But since there is always ‘I’, and ‘We’, and ‘I’, with no boundary between them, and yet always a boundary, it’s as unrealistic as the ‘island I’ concept. No matter how much we might like to abandon our ‘I’ into someone else’s care - in effect, to try to return to the ‘centre of the universe’ feeling back in the womb - we are different from everyone else: and if we try to pretend otherwise, there’s going to be trouble eventually. By the time we get to classic codependency, the two parties are oscillating between the ‘enclosed’ and ‘outside’ positions:

The inner ‘I’ of the pair is enclosed, protected, yet trapped - there’s a sense of being stifled, a need to break out; the outer ‘I’ feels clung to, is forced to take responsibility for both, and loses the sense of comfort and protection that occurs - for a while - in the ‘enclosed’ position. So the two end up continually changing places, via any - or many - of the classic ‘push-pull’ dynamics: clingy, then withdrawn; responsible, then childish; overpowering, then manipulated; demanding commitment, then fleeing from commitment; and so on. What’s interesting is that whilst each ‘I’ is unstable - sometimes very unstable - their ‘We’ is not: it remains constant, or at least relatively so. Despite all the turmoil, the characteristics - the threads of the wyrd - that are emphasised in their ‘We’ remain much the same throughout: all that changes is which ‘I’ of the two is acting out each characteristic…

There’s a real human need for ‘We’ - that spiritual need for ‘that which is greater than self’. In dependent relationships - and especially in codependent relationships - what’s missing is awareness: the apparent need to hold onto ‘We’ at any cost is allowed to take priority over almost any awareness of the personal choices of ‘I’. That creates the tension, because every now and then one or other party will notice that what they’re doing is not what they choose; but since their definition of ‘We’ must remain unchanged, the other party finds that their behaviour is automatically changing to compensate. That person then realises that this isn’t what they want either, but equally clings to ‘We’: so round and round the garden they go…

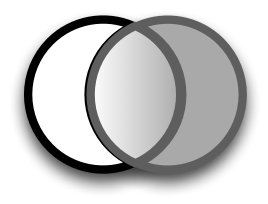

Independence - “I’ll never be in relationship again!” - looks like an alternative, but isn’t, because it happens to be impossible - the wyrd makes certain of that… Inter-dependence, however, is a genuine alternative:

Each ‘I’ is seen as having the same size, the same priority - “the needs, concerns, feelings and fears of [each person] are of exactly equal value and importance”; there’s a full acknowledgement of both ‘I’ and ‘I’. That each has choices that may vary from the shared choices of ‘We’ is also fully acknowledged: in a classic magical perspective, the old Christian symbol of the ‘vesica piscis’ (or fish-bladder shape) between them, is created because the circumference of each one exactly touches the centre of the other. The commitment to ‘We’ is still there, but it is, if anything, stronger than in a dependent relationship; and it changes dynamically, both as the choices of each ‘I’ change, and as their shared choices for ‘We’ change.

Most of all, a stable and constructive ‘We’ depends on awareness: awareness by each ‘I’ of their own choices, for themselves and for their ‘We’; and awareness also of the natural weirdness in the interweaving threads of ‘We’.

The interweaving of We

‘We’ is the interweaving of ‘I’ and ‘I’; ‘We’ is a kind of compound-‘I’ created by and between us. ‘We’ is not that which changes; ‘We’ is that which ‘I’ and ‘I’ chooses. And it has characteristics of its own: so much so that a company, for example, is legally a separate entity, a ‘person’ in its own right, and defined as a chosen type of relationship between people. A company’s ‘purpose statement’ is a formal statement of the choices - the function and direction - that make up that ‘We’; and if we take up a job with a company whose purpose is unclear, or which clashes with our own choice for ‘I’, there’s going to be trouble… usually for us, since the company’s ‘We’ is considerably larger, and naturally tends to subsume others’ choices into itself. In fact any large group tends to develop its own ‘We’, its own direction, its own habitual choices: the ‘We’ of a football crowd is usually noisy and territorial, whilst a crowd of shoppers out bargain-hunting in the ‘Sales’ season has a ‘We’ that’s usually quite a bit quieter, but can be very possessive…

So we need to understand the boundary between ‘I’ and ‘We’ and ‘I’. The problem is that there isn’t one as such: there is a boundary between each, but the boundary blurs, because our own boundaries are blurred, and overlap with everyone else.

The boundary - whatever it is - denotes the limits of what we might call ‘personal space’: which takes us straight back to that ‘I’m the centre of the universe’ problem. If I expand my sense of personal space right out to infinity, then I’m again ‘the centre of the universe’: everything is me, everything is mine. But it includes, or overlaps, or interweaves, with everyone else’s personal space - which also, in principle at least, stretch out to infinity. Reality Department requires us to share, whether we like it or not: so what we sense as our boundaries denotes the limits of ‘me, mine’, outside of which we feel comfortable sharing, but within which we don’t want to share - or don’t feel safe in sharing.

Like ‘I’ itself, every boundary is a choice: do I, or We, choose to feel open to - overlap with - this person’s ‘I’, or not? At this moment, in this circumstance, are their choices - or what I sense as their choices - compatible with mine? The point at which the answer changes from ‘Yes’ to ‘No’ is what we feel as our boundary. When someone else’s choices, for whatever reason, happen to pass that point, we then have another choice: to pull in our ‘personal space’ to a smaller boundary; to accept the feeling of ‘unsafety’, and work with the fears that arise with it; or to blame the other person entirely for the transgression, and try to force them to change their choices, so that we don’t have to take responsibility for ours. In these paediarchal days, where so many people are taught that safety is their ‘right’ but never their responsibility, guess which of these options is more popular? Time to look more closely at boundaries!