Appendix 4: Mathematics of HTM

This article describes some of the mathematics underlying the theory and implementations of Jeff Hawkins’ Hierarchical Temporal Memory (HTM), which seeks to explain how the neocortex processes information and forms models of the world.

The HTM Model Neuron - Pattern Memory (aka Spatial Pooling)

We’ll illustrate the mathematics of HTM by describing the simplest operation in HTM’s Cortical Learning Algorithm: Pattern Memory, also known as Spatial Pooling, forms a Sparse Distributed Representation from a binary input vector. We begin with a layer (a 1- or 2-dimensional array) of single neurons, which will form a pattern of activity aimed at efficiently representing the input vectors.

Feedforward Processing on Proximal Dendrites

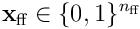

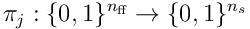

The HTM model neuron has a single proximal dendrite, which is used to process and recognise feedforward or afferent inputs to the neuron. We model the entire feedforward input to a cortical layer as a bit vector  , where

, where  is the width of the input.

is the width of the input.

The dendrite is composed of  synapses which each act as a binary gate for a single bit in the input vector. Each synapse has a permanence

synapses which each act as a binary gate for a single bit in the input vector. Each synapse has a permanence ![p_ i\in{[0,1]}](/preview_site_images/realsmartmachines/leanpub_equation_3.png) which represents the size and efficiency of the dendritic spine and synaptic junction. The synapse will transmit a 1-bit (or on-bit) if the permanence exceeds a threshold

which represents the size and efficiency of the dendritic spine and synaptic junction. The synapse will transmit a 1-bit (or on-bit) if the permanence exceeds a threshold  (often a global constant

(often a global constant  ). When this is true, we say the synapse is connected.

). When this is true, we say the synapse is connected.

Each neuron samples  bits from the

bits from the  feedforward inputs, and so there are

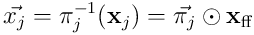

feedforward inputs, and so there are  possible choices of input for a single neuron. A single proximal dendrite represents a projection

possible choices of input for a single neuron. A single proximal dendrite represents a projection  , so a population of neurons corresponds to a set of subspaces of the sensory space. Each dendrite has an input vector

, so a population of neurons corresponds to a set of subspaces of the sensory space. Each dendrite has an input vector  which is the projection of the entire input into this neuron’s subspace.

which is the projection of the entire input into this neuron’s subspace.

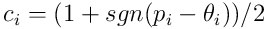

A synapse is connected if its permanence  exceeds its threshold

exceeds its threshold  . If we subtract

. If we subtract  , take the elementwise sign of the result, and map to

, take the elementwise sign of the result, and map to  , we derive the binary connection vector

, we derive the binary connection vector  for the dendrite. Thus:

for the dendrite. Thus:

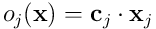

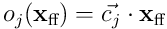

The dot product  now represents the feedforward overlap of the neuron with the input, ie the number of connected synapses which have an incoming activation potential. Later, we’ll see how this number is used in the neuron’s processing.

now represents the feedforward overlap of the neuron with the input, ie the number of connected synapses which have an incoming activation potential. Later, we’ll see how this number is used in the neuron’s processing.

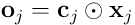

The elementwise product  is the vector in the neuron’s subspace which represents the input vector

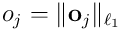

is the vector in the neuron’s subspace which represents the input vector  as “seen” by this neuron. This is known as the overlap vector. The length

as “seen” by this neuron. This is known as the overlap vector. The length  of this vector corresponds to the extent to which the neuron recognises the input, and the direction (in the neuron’s subspace) is that vector which has on-bits shared by both the connection vector and the input.

of this vector corresponds to the extent to which the neuron recognises the input, and the direction (in the neuron’s subspace) is that vector which has on-bits shared by both the connection vector and the input.

If we project this vector back into the input space, the result  is this neuron’s approximation of the part of the input vector which this neuron matches. If we add a set of such vectors, we will form an increasingly close approximation to the original input vector as we choose more and more neurons to collectively represent it.

is this neuron’s approximation of the part of the input vector which this neuron matches. If we add a set of such vectors, we will form an increasingly close approximation to the original input vector as we choose more and more neurons to collectively represent it.

Sparse Distributed Representations (SDRs)

We now show how a layer of neurons transforms an input vector into a sparse representation. From the above description, every neuron is producing an estimate  of the input

of the input  , with length

, with length  reflecting how well the neuron represents or recognises the input. We form a sparse representation of the input by choosing a set

reflecting how well the neuron represents or recognises the input. We form a sparse representation of the input by choosing a set  of the top

of the top  neurons, where

neurons, where  is the number of neurons in the layer, and

is the number of neurons in the layer, and  is the chosen sparsity we wish to impose (typically

is the chosen sparsity we wish to impose (typically  ).

).

The algorithm for choosing the top  neurons may vary. In neocortex, this is achieved using a mechanism involving cascading inhibition: a cell firing quickly (because it depolarises quickly due to its input) activates nearby inhibitory cells, which shut down neighbouring excitatory cells, and also trigger further nearby inhibitory cells, spreading the inhibition outwards. This type of local inhibition can also be used in software simulations, but it is expensive and is only used where the design involves spatial topology (ie where the semantics of the data is to be reflected in the position of the neurons). A more efficient global inhibition algorithm - simply choosing the top

neurons may vary. In neocortex, this is achieved using a mechanism involving cascading inhibition: a cell firing quickly (because it depolarises quickly due to its input) activates nearby inhibitory cells, which shut down neighbouring excitatory cells, and also trigger further nearby inhibitory cells, spreading the inhibition outwards. This type of local inhibition can also be used in software simulations, but it is expensive and is only used where the design involves spatial topology (ie where the semantics of the data is to be reflected in the position of the neurons). A more efficient global inhibition algorithm - simply choosing the top  neurons by their depolarisation values - is often used in practise.

neurons by their depolarisation values - is often used in practise.

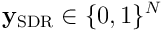

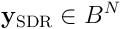

If we form a bit vector  , we have a function which maps an input

, we have a function which maps an input  to a sparse output

to a sparse output  , where the length of each output vector is

, where the length of each output vector is  .

.

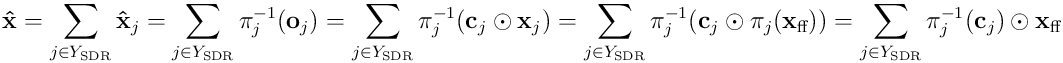

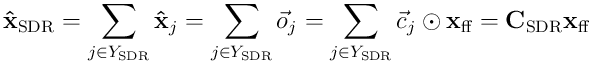

The reverse mapping or estimate of the input vector by the set  of neurons in the SDR is given by the sum:

of neurons in the SDR is given by the sum:

Matrix Form

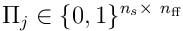

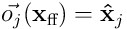

The above can be represented straightforwardly in matrix form. The projection  can be represented as a matrix

can be represented as a matrix  .

.

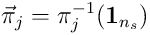

Alternatively, we can stay in the input space  , and model

, and model  as a vector

as a vector  , ie where

, ie where  .

.

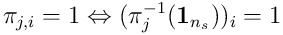

The elementwise product  represents the neuron’s view of the input vector

represents the neuron’s view of the input vector  .

.

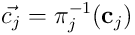

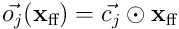

We can similarly project the connection vector for the dendrite by elementwise multiplication:  , and thus

, and thus  is the overlap vector projected back into

is the overlap vector projected back into  , and the dot product

, and the dot product  gives the same overlap score for the neuron given

gives the same overlap score for the neuron given  as input. Note that

as input. Note that  , the partial estimate of the input produced by neuron

, the partial estimate of the input produced by neuron  .

.

We can reconstruct the estimate of the input by an SDR of neurons  :

:

where  is a matrix formed from the

is a matrix formed from the  for

for  .

.

Optimisation Problem

We can now measure the distance between the input vector  and the reconstructed estimate

and the reconstructed estimate  by taking a norm of the difference. Using this, we can frame learning in HTM as an optimisation problem. We wish to minimise the estimation error over all inputs to the layer. Given a set of (usually random) projection vectors

by taking a norm of the difference. Using this, we can frame learning in HTM as an optimisation problem. We wish to minimise the estimation error over all inputs to the layer. Given a set of (usually random) projection vectors  for the N neurons, the parameters of the model are the permanence vectors

for the N neurons, the parameters of the model are the permanence vectors  , which we adjust using a simple Hebbian update model.

, which we adjust using a simple Hebbian update model.

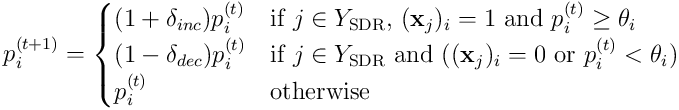

The update model for the permanence of a synapse  on neuron

on neuron  is:

is:

This update rule increases the permanence of active synapses, those that were connected to an active input when the cell became active, and decreases those which were either disconnected or received a zero when the cell fired. In addition to this rule, an external process gently boosts synapses on cells which either have a lower than target rate of activation, or a lower than target average overlap score.

I do not yet have the proof that this optimisation problem converges, or whether it can be represented as a convex optimisation problem. I am confident such a proof can be easily found. Perhaps a kind reader who is more familiar with a problem framed like this would be able to confirm this. I’ll update this post with more functions from HTM in coming weeks.

Transition Memory - Making Predictions

In Part One, we saw how a layer of neurons learns to form a Sparse Distributed Representation (SDR) of an input pattern. In this section, we’ll describe the process of learning temporal sequences.

We showed in part one that the HTM model neuron learns to recognise subpatterns of feedforward input on its proximal dendrites. This is somewhat similar to the manner by which a Restricted Boltzmann Machine can learn to represent its input in an unsupervised learning process. One distinguishing feature of HTM is that the evolution of the world over time is a critical aspect of what, and how, the system learns. The premise for this is that objects and processes in the world persist over time, and may only display a portion of their structure at any given moment. By learning to model this evolving revelation of structure, the neocortex can more efficiently recognise and remember objects and concepts in the world.

Distal Dendrites and Prediction

In addition to its one proximal dendrite, a HTM model neuron has a collection of distal (far) dendrite segments (or simply dendrites), which gather information from sources other than the feedforward inputs to the layer. In some layers of neocortex, these dendrites combine signals from neurons in the same layer as well as from other layers in the same region, and even receive indirect inputs from neurons in higher regions of cortex. We will describe the structure and function of each of these.

The simplest case involves distal dendrites which gather signals from neurons within the same layer.

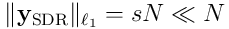

In Part One, we showed that a layer of  neurons converted an input vector

neurons converted an input vector  into a SDR

into a SDR  , with length

, with length , where the sparsity

, where the sparsity  is usually of the order of 2% (

is usually of the order of 2% ( is typically 2048, so the SDR

is typically 2048, so the SDR  will have 40 active neurons).

will have 40 active neurons).

The layer of HTM neurons can now be extended to treat its own activation pattern as a separate and complementary input for the next timestep. This is done using a collection of distal dendrite segments, which each receive as input the signals from other neurons in the layer itself. Unlike the proximal dendrite, which transmits signals directly to the neuron, each distal dendrite acts individually as an active coincidence detector, firing only when it receives enough signals to exceed its individual threshold.

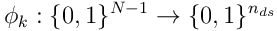

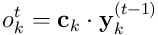

We proceed with the analysis in a manner analogous to the earlier discussion. The input to the distal dendrite segment  at time

at time  is a sample of the bit vector

is a sample of the bit vector  . We have

. We have  distal synapses per segment, a permanence vector

distal synapses per segment, a permanence vector ![\mathbf{p}_ k \in [0,1]^ {n_ {ds}}](/preview_site_images/realsmartmachines/leanpub_equation_76.png) and a synapse threshold vector

and a synapse threshold vector ![\vec{\theta}_ k \in [0,1]^ {n_ {ds}}](/preview_site_images/realsmartmachines/leanpub_equation_77.png) , where typically

, where typically  for all synapses.

for all synapses.

Following the process for proximal dendrites, we get the distal segment’s connection vector  :

:

The input for segment  is the vector

is the vector  formed by the projection

formed by the projection  from the SDR to the subspace of the segment. There are

from the SDR to the subspace of the segment. There are  such projections (there are no connections from a neuron to itself, so there are

such projections (there are no connections from a neuron to itself, so there are  to choose from).

to choose from).

The overlap of the segment for a given  is the dot product

is the dot product  . If this overlap exceeds the threshold

. If this overlap exceeds the threshold  of the segment, the segment is active and sends a dendritic spike of size

of the segment, the segment is active and sends a dendritic spike of size  to the neuron’s cell body.

to the neuron’s cell body.

This process takes place before the processing of the feedforward input, which allows the layer to combine contextual knowledge of recent activity with recognition of the incoming feedforward signals. In order to facilitate this, we will change the algorithm for Pattern Memory as follows.

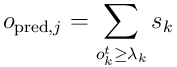

Each neuron  begins a timestep

begins a timestep  by performing the above processing on its

by performing the above processing on its  distal dendrites. This results in some number

distal dendrites. This results in some number  of segments becoming active and sending spikes to the neuron. The total predictive activation potential is given by:

of segments becoming active and sending spikes to the neuron. The total predictive activation potential is given by:

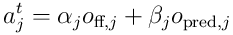

The predictive potential is combined with the overlap score from the feedforward overlap coming from the proximal dendrite to give the total activation potential:

and these  potentials are used to choose the top neurons, forming the SDR

potentials are used to choose the top neurons, forming the SDR  at time

at time  . The mixing factors

. The mixing factors  and

and  are design parameters of the simulation.

are design parameters of the simulation.

Learning Predictions

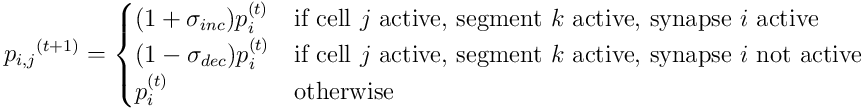

We use a very similar learning rule for distal dendrite segments as we did for the feedforward inputs:

Again, this reinforces synapses which contribute to activity of the cell, and decreases the contribution of synapses which don’t. A boosting rule, similar to that for proximal synapses, allows poorly performing distal connections to improve until they are good enough to use the main rule.

Interpretation

We can now view the layer of neurons as forming a number of representations at each timestep. The field of predictive potentials  can be viewed as a map of the layer’s confidence in its prediction of the next input. The field of feedforward potentials

can be viewed as a map of the layer’s confidence in its prediction of the next input. The field of feedforward potentials  can be viewed as a map of the layer’s recognition of current reality. Combined, these maps allow for prediction-assisted recognition, which, in the presence of temporal correlations between sensory inputs, will improve the recognition and representation significantly.

can be viewed as a map of the layer’s recognition of current reality. Combined, these maps allow for prediction-assisted recognition, which, in the presence of temporal correlations between sensory inputs, will improve the recognition and representation significantly.

We can quantify the properties of the predictions formed by such a layer in terms of the mutual information between the SDRs at time  and

and  . I intend to provide this analysis as soon as possible, and I’d appreciate the kind reader’s assistance if she could point me to papers which might be of help.

. I intend to provide this analysis as soon as possible, and I’d appreciate the kind reader’s assistance if she could point me to papers which might be of help.

A layer of neurons connected as described here is a Transition Memory, and is a kind of first-order memory of temporally correlated transitions between sensory patterns. This kind of memory may only learn one-step transitions, because the SDR is formed only by combining potentials one timestep in the past with current inputs.

Since the neocortex clearly learns to identify and model much longer sequences, we need to modify our layer significantly in order to construct a system which can learn high-order sequences. This is the subject of the next part of this Appendix.

Note: For brevity, I’ve omitted the matrix treatment of the above. See Part One for how this is done for Pattern Memory; the extension to Transition Memory is simple but somewhat arduous.