Chapter 5: Functor, Bifunctor, Trifunctor?

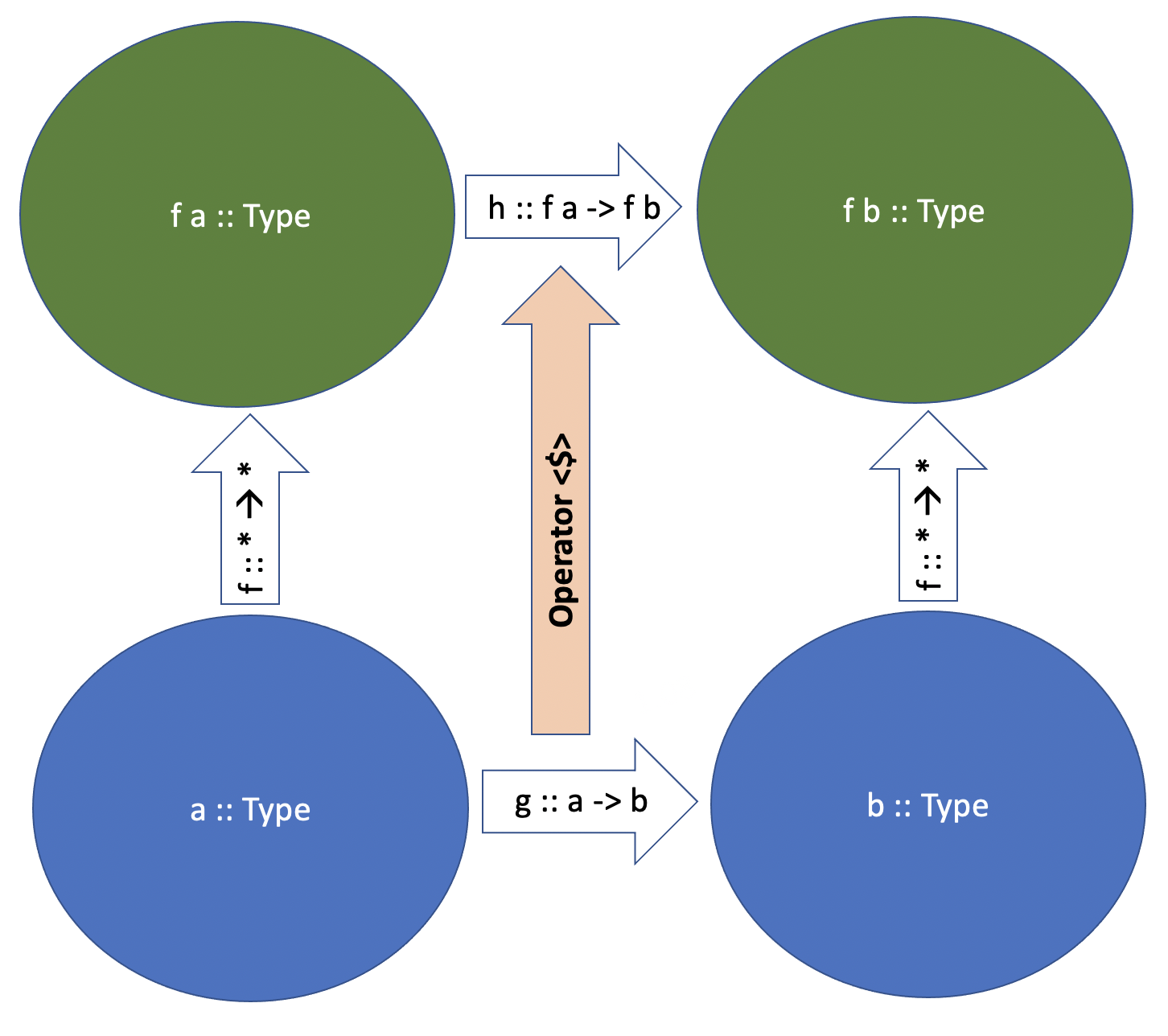

Recall how we “invented” a Functor a couple of chapters ago when we needed a good way to apply functions between two concrete types \(a \rightarrow b\) to values of List a or Maybe a? To recap, a Functor is merely any type function f :: * -> *, like Maybe a or list [a] that has an operator <$> defined, which “converts” or lifts functions between two concrete types – g :: a -> b – to functions between values of types constructed from a and b with the help of our type function f – h :: f a -> f b.

In Haskell, Functor is also a typeclass, which we will fully define and discuss below. Making your types an instance of a Functor is a very good way to avoid writing a lot of boilerplate code. If you have some experience with imperative languages such as C++ or Java, it can be a good exercise to try to define a Functor for C++ templates or Java generics - which are as close as those can get to typeclasses. Once you spend an hour writing <$> for a List and a Maybe, and trying to generalize the approach - you will start appreciating the beauty and consizeness of Haskell a great deal.

Since both Maybe a and [a] are instances of a Functor, you can write extremely concise code such as (*2) <$> (Just 4) or (++ " hello") <$> ["world", "me"] instead of writing a separate function with nested case analysis statements each time. That’s one of the reasons you can’t evaluate Haskell programmers performance in “lines of code” - if anything, we pride ourselves in having as few lines of code as possible to achieve a goal.

Strictly speaking, a Functor is not only a type function \(f : * \rightarrow *\) with the “lifting” operator <$> defined, but it also has some laws - just like a Monoid which we discussed in the previous section. The laws are as follows:

- (<$>) id == id – identity function should remain an identity function even when lifted.

- (<$>) (f • g) == (<$>) f • (<$>) g – function composition must be respected - whether we lift a composed function f•g or lift f first, then g, and then compose them - the result should be the same.

Formal(ish) type-theoretic definition of our Functor can be given as follows:

Here fmap is simply a synonim for the infix operator <$>. As a Haskell typeclass, Functor is defined with a bunch of additional useful functions with default implementation - again, just as we have seen with Monoid:

1 class Functor f where

2 fmap :: (a -> b) -> f a -> f b

So how would you use Functor abstraction in real life? If you know some type function is an instance of a Functor - such as Maybe or List - you can use fmap or <$> to easily “lift” any a -> b function application to a value of such a type. When you design a new type function f :: * -> * that takes a type and creates another type out of it - think if you can make it an instance of a Functor so that your code is concise and maintainable. It is trivially useful for all kinds of containers other than list, but every time you see a data type in Haskell with type signature * -> * - it’s worth checking if it is a Functor or whether it can be made one. This is also a good exercise to develop your intuition for other abstractions, such as Applicative and Monad that we will look at in the next sections. They are nothing scarier than a Functor - in fact, they are a Functor just with some more structure added!

3-Dimensional Vector Example

Let’s work through a simplified example for the task above. Suppose we are developing a physics model where we need to store 3-dimensional coordinates in a vector, but we may want to use Double or Int or even complex numbers as elements of our vector. We can define the following type for this purpose:

1 data Vector3 a = Vec3 a a a

Now, in real life there are much more efficient data structures for such a task, so please never model real physics with a data structure as above, but it helps to work through such a simplified example to understand more complex types later on. Based on this definition, we can have Vector3 Double or Vector3 Int, while defining polymporphic vector-related functions such as summation, dot product, etc.

Can we make our type an instance of a Functor? It has the right type - Vector3 :: * -> * - as it takes a concrete type and makes another type out of it. To turn it into a functor, we need to define the function fmap that will have the following type signature: fmap :: (a -> b) -> Vector3 a -> Vector3 b. Just by looking at the signature we can see such a function would be quite useful - we would definitely want to convert a Vector3 Int into Vector3 Double and since there is a function already that converts Int to Double (fromIntegral) - so if we have an fmap as above we can simply lift it and not worry about writing a separate conversion function for each case!

Let’s define it:

1 instance Functor Vector3 where

2 fmap f (Vec3 x y z) = Vec3 (f x) (f y) (f z)

So, we simply apply function f::a->b to all components of our vector and return a new vector, very easy and makes sense!

You are Either Functor or a Bifunctor

By now you should have seen that there is nothing scary about a Functor save for a name. In this section, we will look at type functions from several type parameters and will easily invent something sounding even scarier than a Functor - a Bifunctor, which is again just another useful and natural abstraction.

So far, we have looked at the type functions with the type * -> * such as Maybe a or [a]. However, nothing prevents us from writing type functions with several type parameters - however many we want, just as with “real” functions. The simplest example of such a type is Either:

1 data Either a b = Left a | Right b

If we write down Either with full type it will be Either :: * -> * -> *, which reads simply as “give me two concrete types and I’ll make a new concrete type out of it”. It has two data constructors and is very similar to Maybe with the key difference being that instead of Nothing as the second data constructor, here we can actually store some info along with it. As such, its most popular use is also for handling errors or failure, just as Maybe, but with additional information. Consider the safeDivide function we defined before:

1 safeDivide :: Double -> Double -> Maybe Double

2 safeDivide _ 0 = Nothing

3 safeDivide x y = x / y

In case someone divides by zero using our safeDivide it won’t break or throw an exception, it will simply return Nothing - so we can continue our safe computations. But what if we want to return some more information in case of errors, or if we want to distinguish between errors? We can use Either a b! For instance:

1 verySafeDivide :: Double -> Double -> Either String Double

2 verySafeDivide _ 0 = Left "Please don't divide by zero!"

3 verySafeDivide _ 100 = Left "We don't want you to divide by 100 either!"

4 verySafeDivide x y = Right (x / y)

This function takes two doubles and returns a value of type Either String Double. From its definition the pattern of usage is pretty obvious - errors are marked with Left data constructor, “regular” results - with Right. Pretty cool and more useful than Maybe in many more complex cases (of course we don’t really need Either for safe arithmetic, but in many real-world cases it it very handy).

However, here we immediately run into an issue by asking the same question as in chapter 2 - what if I want to square the result of our verySafeDivide operation? For Maybe, we have a Functor instance, so we can simply write square <$> safeDivide 4 3 and it will work like a charm. But we cannot turn Either a b into a Functor, it has the wrong type for it! Functor expects * -> *, and Either has * -> * -> *. So what do we do? Are we forced to write long and ugly “case” analysis functions to be able to use Either?

Of course not, that is not the Haskell way! We can design another generic function and see if it can be abstracted away into some other typeclass similar to a Functor. What we need to apply square to verySafeDivide is a function that takes Double -> Double and makes it work with Either String Double, so that we can write something like eitherLift square (verySafeDivide 5 2) and it would work. Let’s write it:

1 eitherLift :: (Double -> Double) -> Either String Double -> Either String Double

2 eitherLift f (Left err) = Left $ "Applied a function to an error message: " ++ err

3 eitherLift f (Right res) = Right (f res)

If we are giving an error (Left value) to eitherLift it simply translates the error further, if we are giving a proper result (Right value) - we apply the function and put it under another Right value. Clean and easy, and very similar to what we did when we invented lifting for Maybe Double, right?

So how about we generalize it further, by looking at the above and squinting hard, and deciding that what we really want is the function with the following type signature:

1 eitherMap :: (a -> c) -> (b -> d) -> (Either a b -> Either c d)

Just like our maybeMap took a function between a -> b and “lifted it” into Maybe by turning it into a function between Maybe a -> Maybe b, here we take two functions - a -> c and b -> d and lifting them into Either by turning both of them into one function between Either a b -> Either c d.

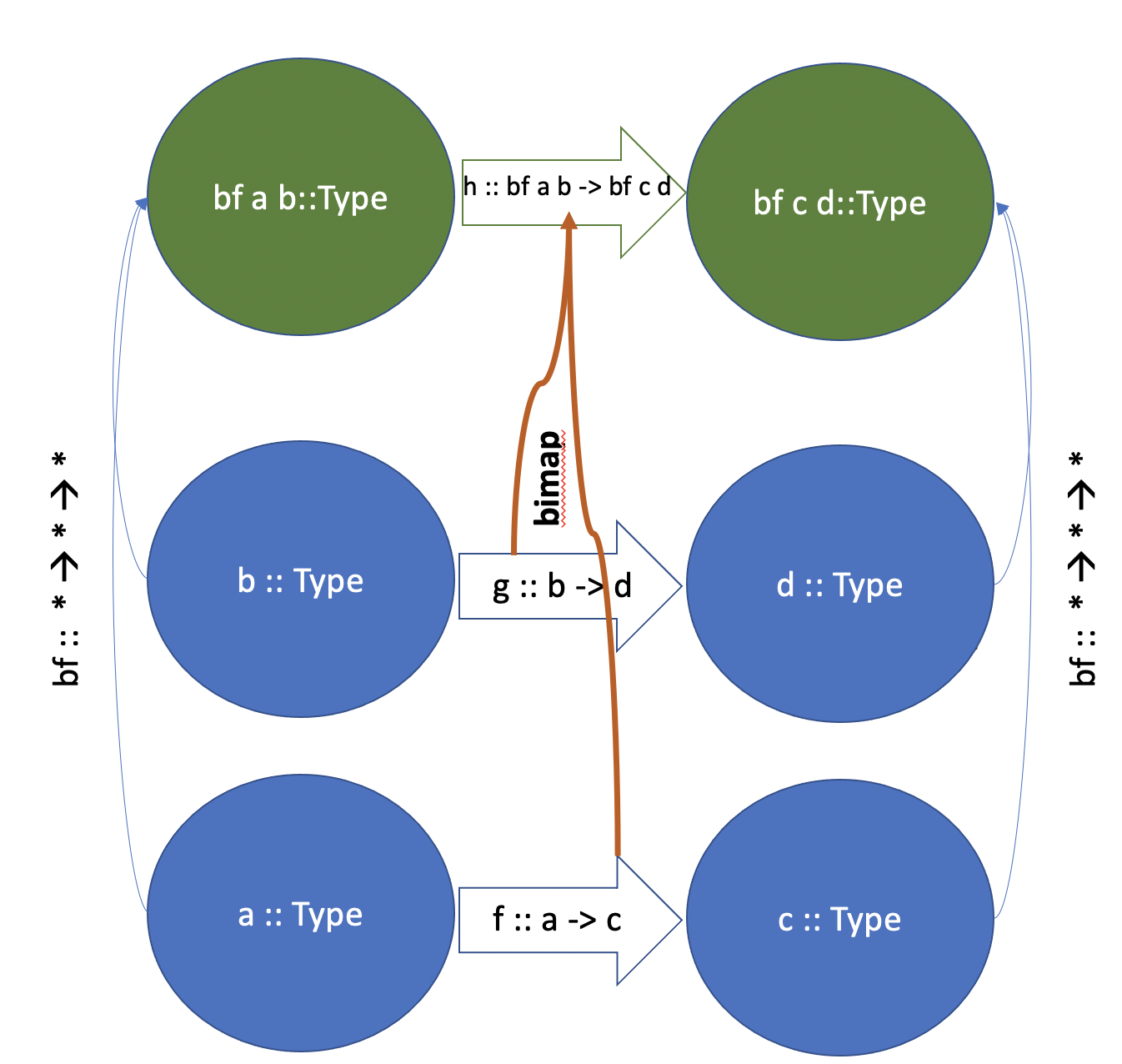

But why stop here? Let’s take it a step further and make such a function not just for Either, but for any type function with type * -> * -> *? This is very similar to what we did when inventing a Functor, only now we invented a Bifunctor:

1 class Bifunctor bf where

2 bimap :: (a -> c) -> (b -> d) -> (bf a b -> bf c d)

So, Bifunctor is a type function with type * -> * -> *, i.e. the one that takes two type parameters and creates a new type, with function bimap defined, which lifts two functions f :: a -> c and g :: b -> d into our Bifunctor by turning them into one function h :: bf a b -> bf c d. Here is a picture to help you visualize the concept:

Do you notice a beautiful symmetry? bf takes two types and “lifts” them in a new type; bimap takes two functions and “lifts” them into new one.

Making Either an instance of Bifunctor is very straightforward:

1 instance Bifunctor Either where

2 bimap f g (Left x) = Left (f x)

3 bimap f g (Right y) = Right (g y)

Again, in a couple of paragraphs of text, by solving a practical task of dealing with errors in our computations, we invented something with a very scary name, which is nothing more than a really cool and useful abstraction for type functions with two type parameters.

You should now be able to rewrite our pretty specific eitherLift function from above via general bimap function. Try doing it on your own before reading further.

To solve this task, you need to realize that we were lifting b -> d function, in our case Double -> Double, while the a -> c one, in our case String -> String was added implicitly in the body of the Left case. Realizing this, we can define eitherLift as follows:

1 eitherLift :: (Double -> Double) -> Either String Double -> Either String Double

2 eitherLift = bimap (\err -> "Applied a function to an error message: " ++ err)

Please dwell on these two lines for some time until you fully understand what is happening here and you are fully convinced this definition is equivalent to the one given above. Strictly speaking, the function above will have a more generic type: eitherLift :: (a -> b) -> Either String a -> Either String b, so we will be able to lift not just functions of type Double -> Double with its help, but functions between any two types a -> b. Convince yourself why this is the case.