Chapter 1: Wizards, Types, and Functions

In this chapter: functional programming is magic * solving problems the functional way * putting something on the screen * introducing types * introducing type functions

Functional Programming Is Magic

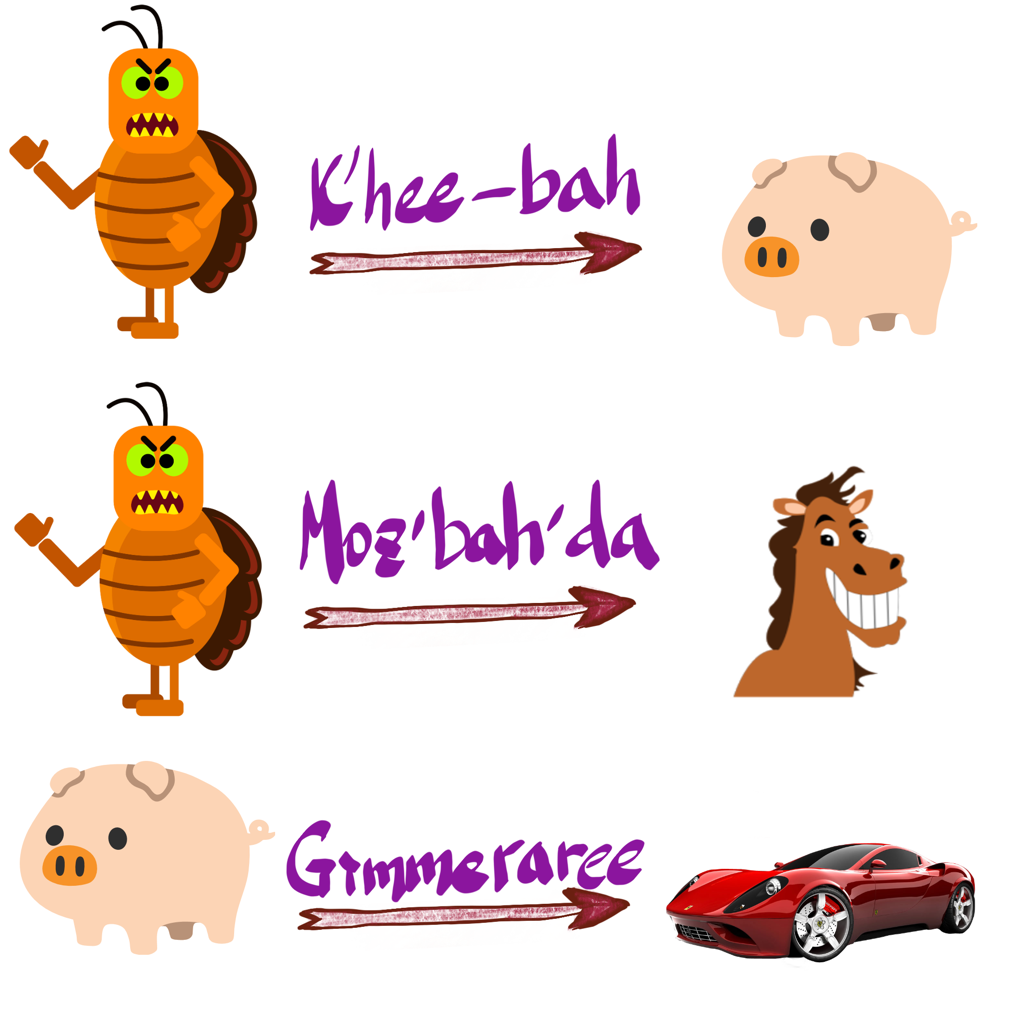

You wake up in a cheap motel room in Brooklyn. You hear police sirens outside, the ceiling is grey and dirty, and a big cockroach is slowly crawling across. You don’t remember much, except that you need to be in a fancy restaurant in Manhattan at 7 pm — oh my, it’s in 15 minutes! — and that you are a wizard. The problem is, you only remember three spells:

You are obviously in a hurry, so, looking attentively at a cockroach, you wave your hands and go: “Moz’bah’da!” — and puff! — there is a beautiful white horse right beside the bed! In a short moment, you realize that riding a horse through New York might not get you there on time, plus you are not sure you even can ride a horse, so you wave your hands again and shout: “Gimmeraree!”

The horse disappears in a puff of smoke, and all you get is a pile of stinking goo on the floor. Oh-oh. You forgot that “Gimmeraree” works only on pigs! Poor horse. You catch another cockroach, go outside, and this time say your spells in the correct order — “K’hee-bah!”, “Gimmeraree!” — and there you go, red Ferrari Spider, in mint condition standing right there besides the garbage bins. Hastily, you jump into the car and drive away to a meeting that will hopefully clear up your past, present, and future destiny.

Typed functional programming is just like magic. Your spells are functions. They turn something into something else (like pigs to Ferraris or strings to numbers) or produce some effect (like putting Ogres to sleep or drawing a circle on the screen), and you need to combine different spells in the right order to get to the desired result.

What happened in the story above was dynamically typed magic: you used a spell that works only on pigs on a horse instead, and your “program” crashed, killing the horse in the process (that’s what often happens with JavaScript programs). With the statically typed magic that we will use from now on, a powerful being called Typechecker would see your mistake, stop your hand, and would tell you that “Gimmeraree” expects a pig as its’ input — which would indeed make you a much more powerful and successful mage than if you go around killing other people’s horses.

Solving Problems As Wizards Do

So how do we approach solving problems the functional way? The mage above needed to get a fast mode of transportation, and all he had were cockroaches. So, he had to think about how he could get from a cockroach to a Ferrari using the spells he knows by combining them in the correct order. He started with an end-result — Ferrari — and worked backward from there, getting to the correct sequence by composing spells that work on the right subjects.

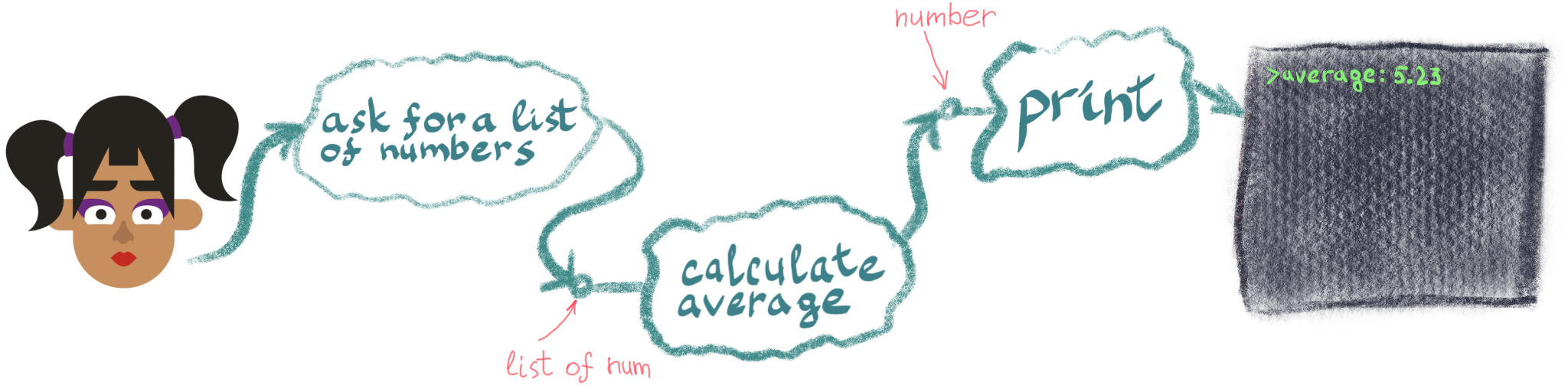

Now, let’s get real and say you need to calculate an average of a list of numbers and show it on the screen. Please resist the imperative urge to start telling the computer what to do and how to do it and let’s focus on the problem as a wizard would instead.

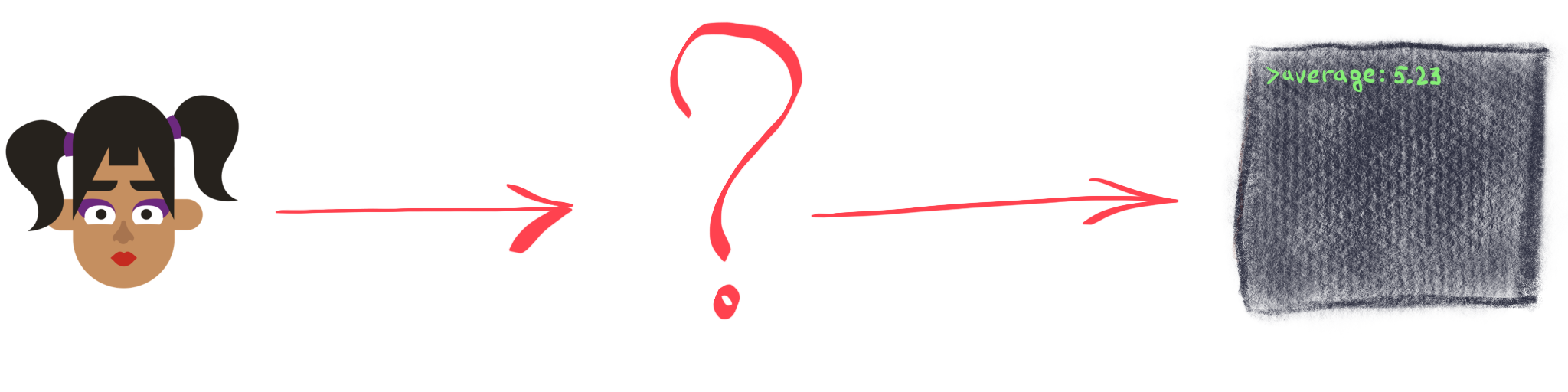

You have a human, and you need to turn her into a line on the screen, hopefully without killing anyone. Let’s work backward from our desired result — “a line on the screen with the average printed out”.

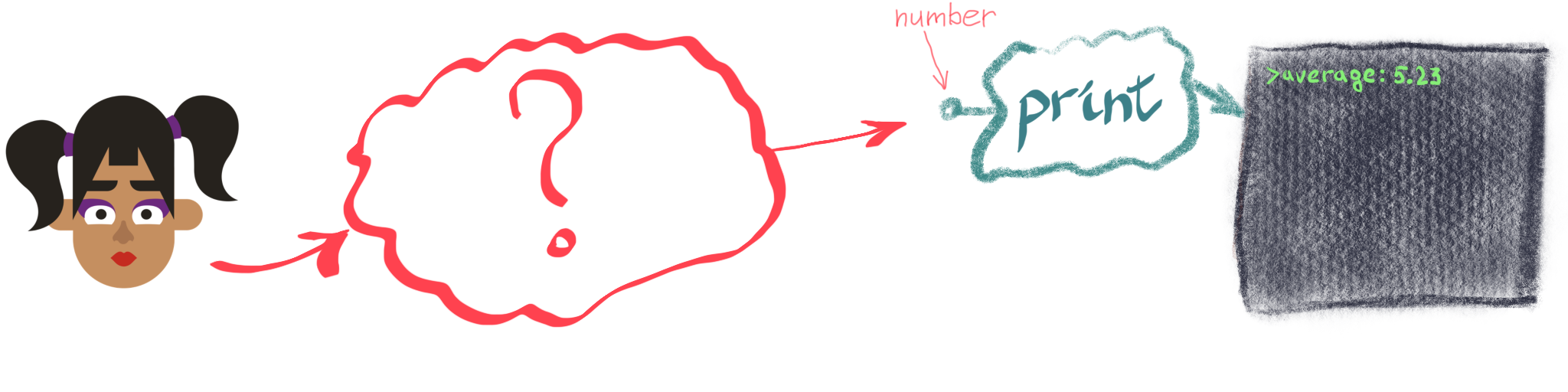

To get to this result, we need something that takes a number and shows it on the screen. Let’s call this something “print”:

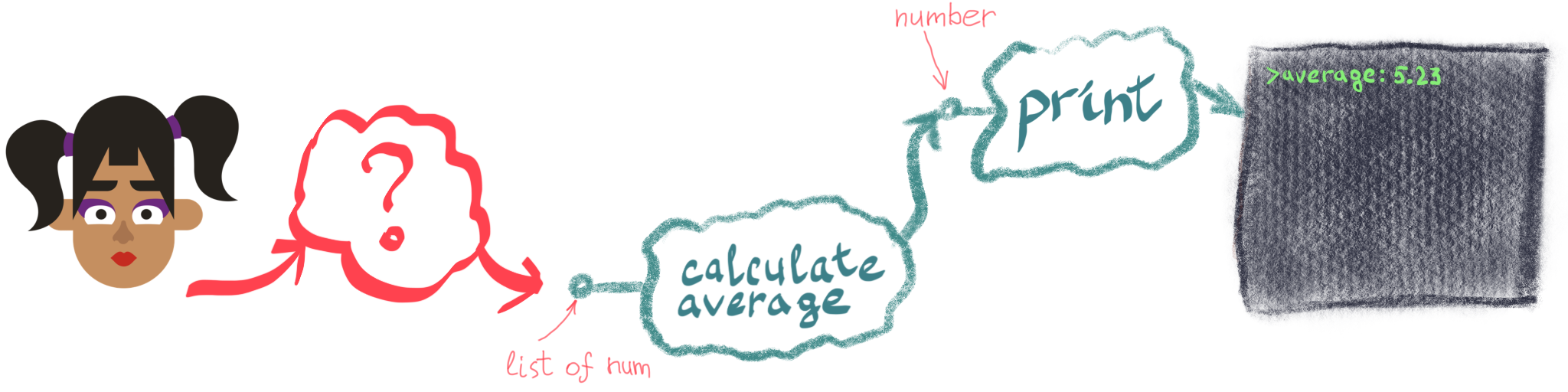

Now our problem is a bit easier - we need to get from a human to a number. “Print”, whatever it is, needs a number to operate. Since our goal is to calculate and show an average value, the previous step needs to take a list of numbers and, uhm, calculate their average:

Our problem became easier still - now we just need to extract the list of numbers from our human and the solution is ready!

What did we just do? We have broken down or decomposed our problem into smaller pieces, solutions to which we already know or can come up with easily enough, and combined them in the right order to get to the desired result. Just like with the mage above, we cannot give a string or a horse to our calculate average - it expects a list of numbers, so it will not compose with functions that produce something other than a list of numbers! Thus, we came up not only with “spells”-functions that we would need to solve our problem, but also with types that our functions should work with: a list of numbers, a number, an effect of putting something on screen. From the start, just by thinking about how to solve a problem, we “invented” two most important concepts in programming, computer science and mathematics itself: Functions and Types.

We’ll start looking at them more closely later on in this chapter. For now, here’s a bit of real magic: as it turns out, Haskell code maps virtually 1:1 to this approach! Look at the first line of the code below (don’t mind the rest for now) and try it live in your browser:

1 main = ask >> getLine >>= toList >>= calcAverage >>= printResult

2

3 where calcAverage l = pure $ (sum l) / (lengthF l)

4 printResult n = putStrLn $ "Average of your list is: " ++ (show n)

5 ask = putStrLn "Enter list of numbers, e.g. [1,3,4,5]:"

6 toList = pure . read

The first line is our sequence of “spells”, or, really, functions, that start with a human sitting at the keyboard and get us to the line on the screen with calculated average shown. First, we ask a human to enter the list of numbers with ask and pass whatever was entered to the next function - toList - to convert the string she enters to an actual List. Resulting list is given to calcAverage function that in turn passes its’ result to printResult. Exactly what we came up with, reasoning about the problem in the passage above.

We started with the desired end result, worked backwards by decomposing the big problem into smaller pieces and connected or composed them so that the output type of one function fits to the input types of the next. This is the essence of every functional program. Lines of code after where further detail how the “spells” we are chaining should behave - don’t concern yourself with them yet. What’s important, is to get a feel of the process:

- What is our desired result?

- What is our input?

- Work backwards from the result to the input, decomposing the problem into smaller pieces that we know how to solve, by thinking about how to convert between types along the way

- Compose smaller functions, each of which solves a smaller problem piece, together into a bigger function, making sure the types fit

Practice this approach on some other problems you would like to solve. We will use it on quite a bit of the real-world problems further along.

Let’s Fall In Love With Types!

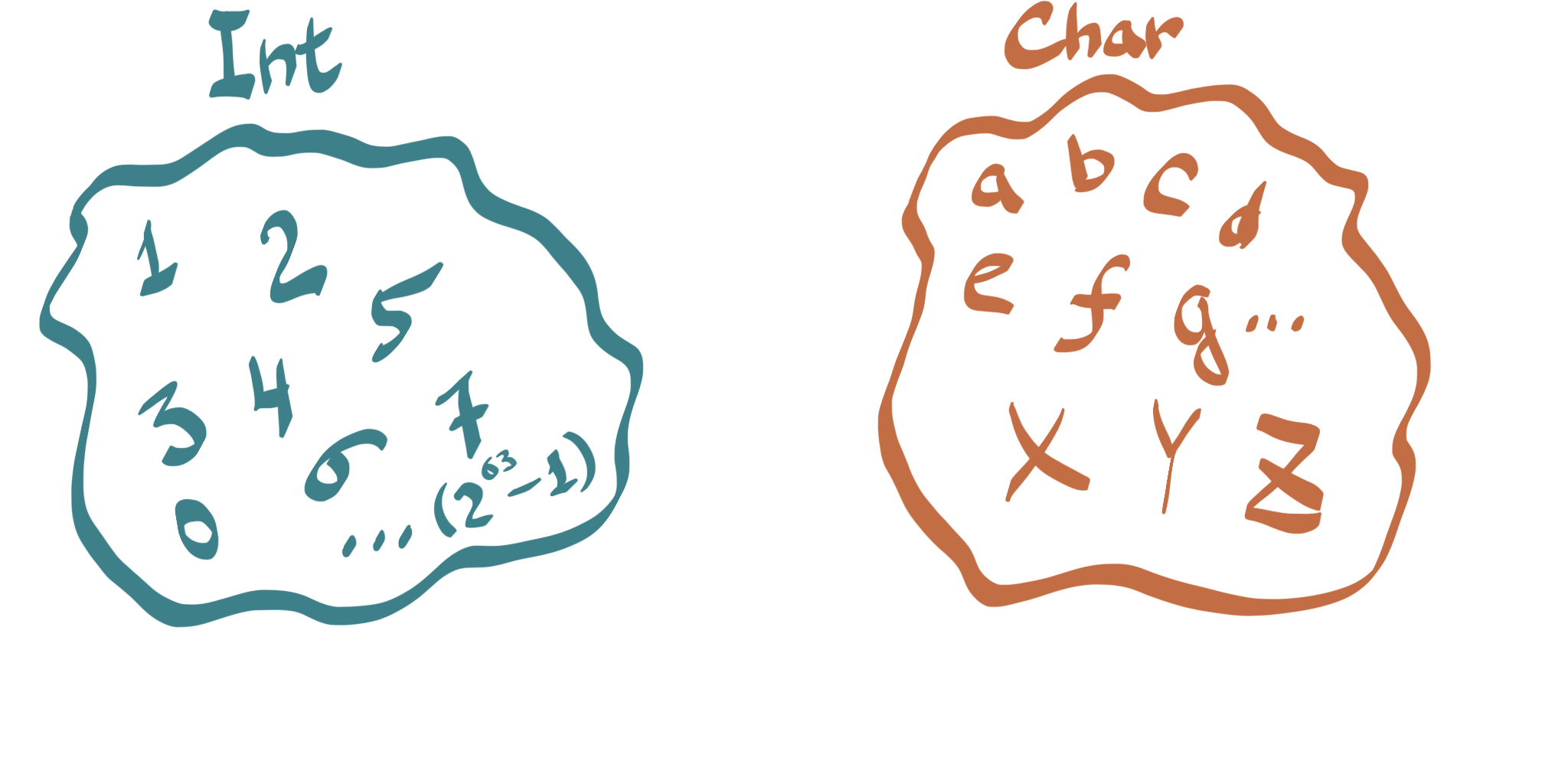

To become a really powerful Haskell mage, you need to get to know and understand Types intimately: Their birth, their daily lives, and their relations with each other. Types come before functions and functions are meaningless without types. So, what are types? Intuitively, a type is just a bunch of objects (or subjects) sharing some common characteristic(s) thrown in a pot together. You could say that the type of your Ferrari Spider is Car, as is the type of that Toyota Prius. The type of both a pig and a horse is Animal. The type of 1, 114, 27428 is Natural Number. The type of the letters ‘a’, ‘C’, ‘e’, ‘z’ is Char (that’s an actual type for characters in Haskell). The last two are ubiquitous in programming, so let’s look at them more closely.

Let’s not forget that we are creative wizards, so we will be building a whole new world from scratch. We will call this world Category ‘Hask’ (for reasons that will become apparent much later), or simply Hask from now on, and it will be inhabited by Types, their members, or values, Functions, and some other interesting characters. As we create this world, we will gradually become more and more powerful, and eventually will be able to write efficient, elegant, and robust Haskell programs for any practical task.

A Char and an Int walk into a bar and make a Function

Natural numbers is the most intuitive math concept that everyone is familiar with - that is what you use when counting times you read confusing monad tutorial articles. Natural numbers start with nothing, zero, and go on forever. Once you subtract the number of times you read confusing monad tutorials (at least 37) from the number of times it made sense (0), you realize the need for negative numbers, which together with naturals give you another infinite type - Integers. Various “ints” that you might be used to from the C-land, as well as the type Int in Haskell, is the teeny-tiny subset of real Integers, limited by 231-1 or 263-1 on the 64-bit systems. What is 9,223,372,036,854,775,807 compared to infinity? Same as nothing, but, fortunately, it is enough for most practical purposes, including counting all the money in the world if you want to write a new Automated Banking System at some point.

Char is our second foundational type - a pot of all characters we use when writing stuff in different languages, including mathematics or Egyptian pictography if we want to get fancy. It is also a finite type and quite a bit smaller than Int at that.

By themselves, these types are quite boring, and we can’t do much with them - it’s just lonely numbers and characters hanging out all by themselves. They are sort of like prisoners in solitary confinement with no way to interact with others. Let’s break them out and set them free to roam the world and talk to each other! To do this, we are going to need functions.

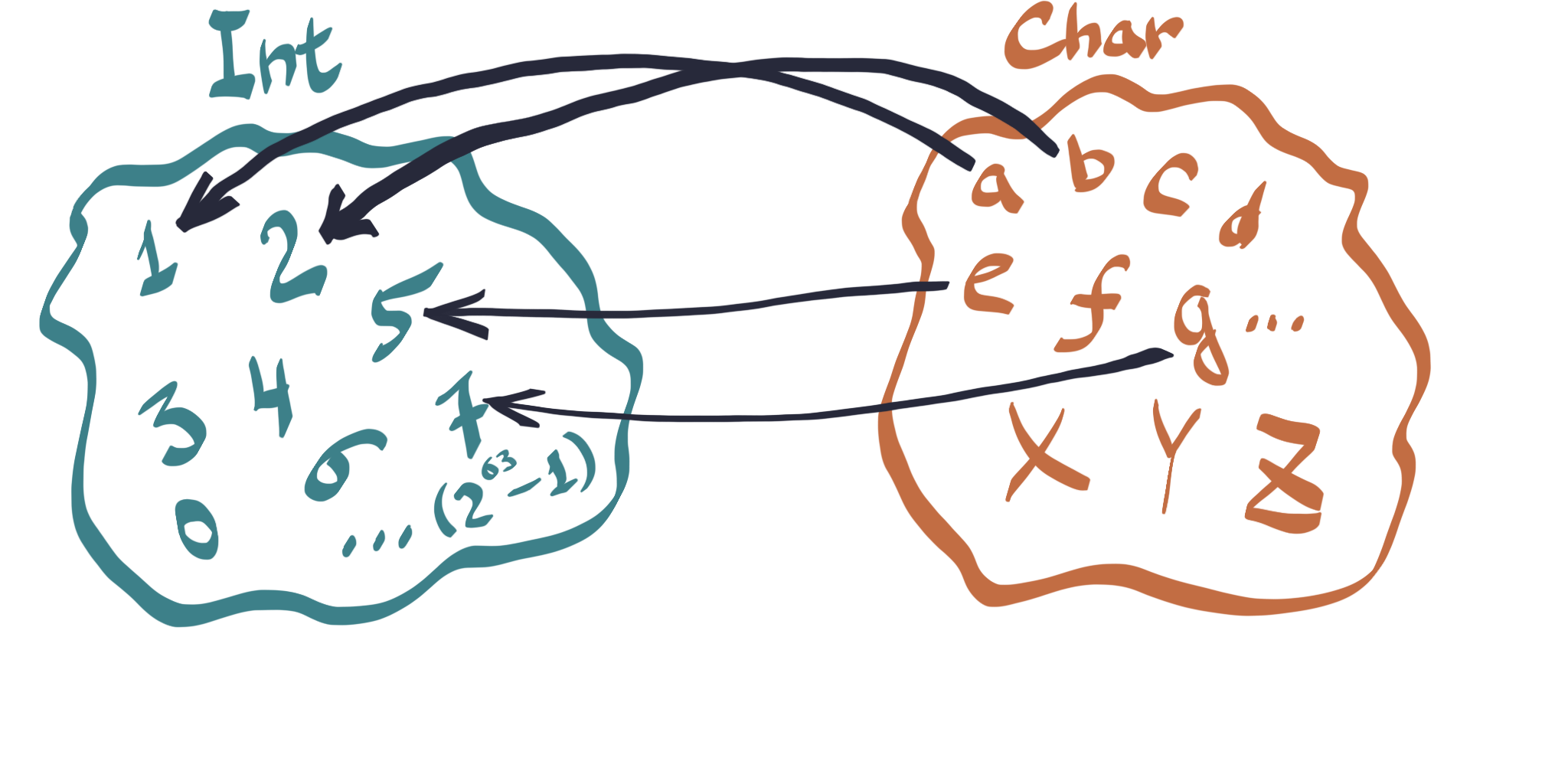

Let’s line up our characters from the Char type as they do in an English alphabet. Then we can ask each letter - “which number are you?” - like in the picture on the right.

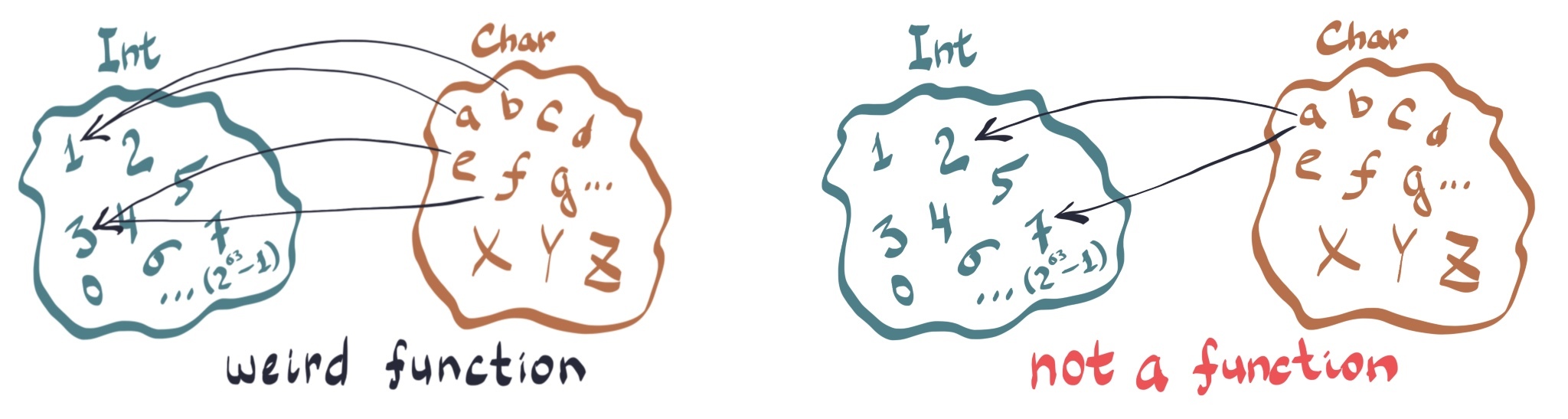

We have just constructed our first function! What it does is match each letter with a number. Now, this is very important: it matches all letters with a number. We could match just some letters to certain numbers - then our function would be called a partial function since it would be defined not for all members of our type. A function can map several members of a type to one member of another type, e.g., we could define a function that matches ‘a’ and ‘b’ to 1, ‘c’ and ‘d’ to 2 etc - it would be a perfectly fine, even if a bit weird, function. However, what we cannot do is define a function that matches a member of a type to several members of another type:

On the other hand, an imperative procedure, for instance, a JavaScript “function”, can take an ‘a’ and return 1 on one day, ‘32’ on another, or crash if the temperature in Alaska drops below zero. Our function, as any other real mathematical function, always gives you the same result for the same arguments, no matter what.

You can trust the word of a function. You cannot trust anything from a procedure.

Our function (let’s call it whichNumberIsChar) takes a Char and gives an Int as a result. In Haskell, we write: whichNumberIsChar :: Char -> Int. You can try it live in your browser here. Just type (cheating a bit since we are using another, much more powerful polymorphic Haskell function to define ours): let whichNumberIsChar = fromEnum :: Char -> Int. Then you can type whichNumberIsChar 'Z' (or some other character) and see what happens.

Our world is still very boring. We have two basic types living in it, and we have one function between them, but we can’t even add two numbers together! That’s not enough to solve a simple calculate an average for some numbers problem, let alone do something more interesting. However, it turns out that Int, Char, and some imagination can get us much further than may appear. Let’s make some more magic!

How FunTypical!

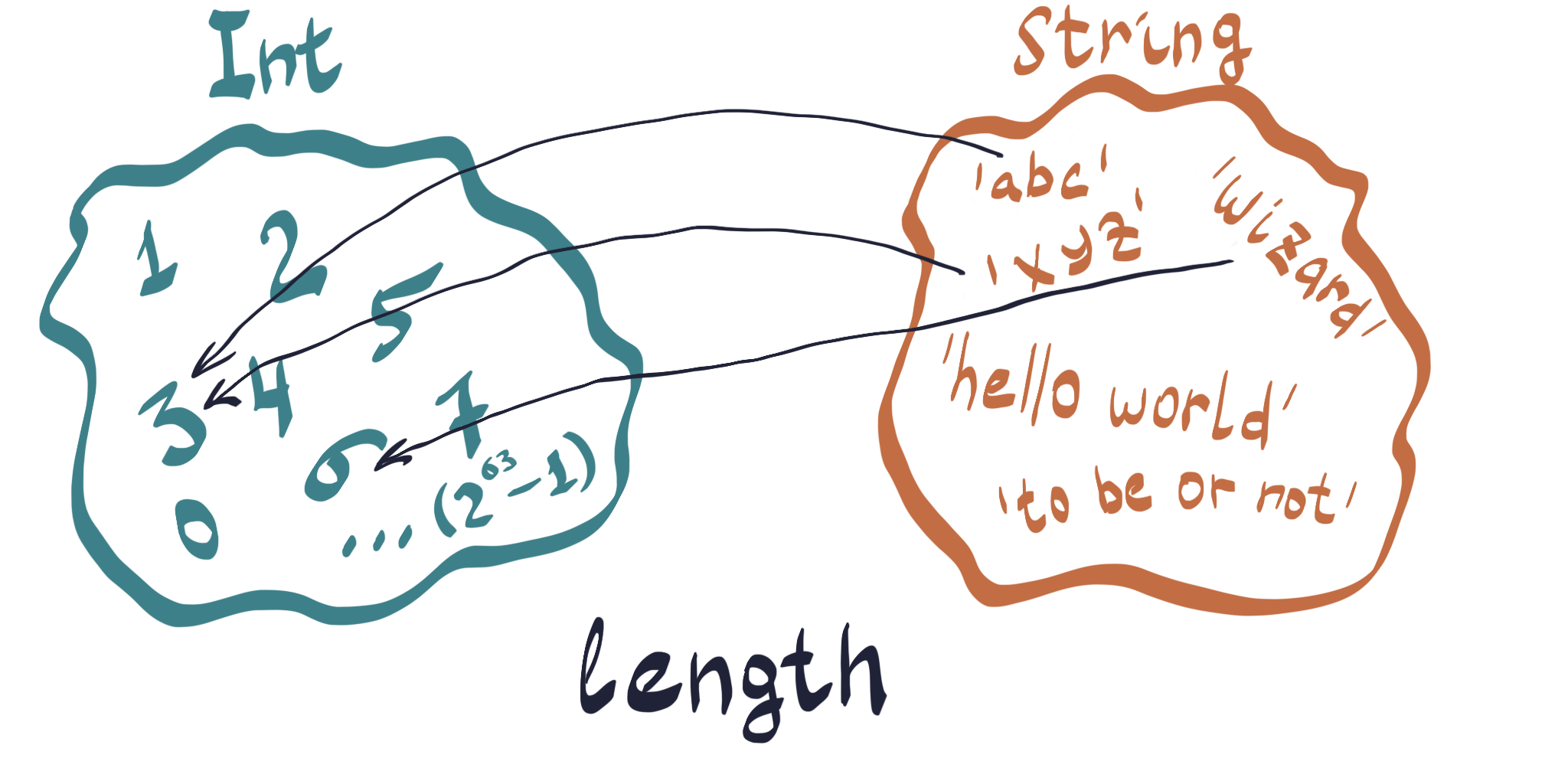

First, we need strings. What is a string? It’s basically just a bunch of characters put together in order. Like “abc”, “xyz” or “Hello World”. This hints at how we can introduce the type String: it’s a set of all possible combinations of characters from Char. Easy, right? We can also introduce another obvious useful function right away, between String and Int, that gives us the length of a string: length :: String -> Int. Try it out in our repl and you should see something like:

1 GHCi, version 8.0.1

2 > length "abc"

3 => 3

4 > length "hello world"

5 => 11

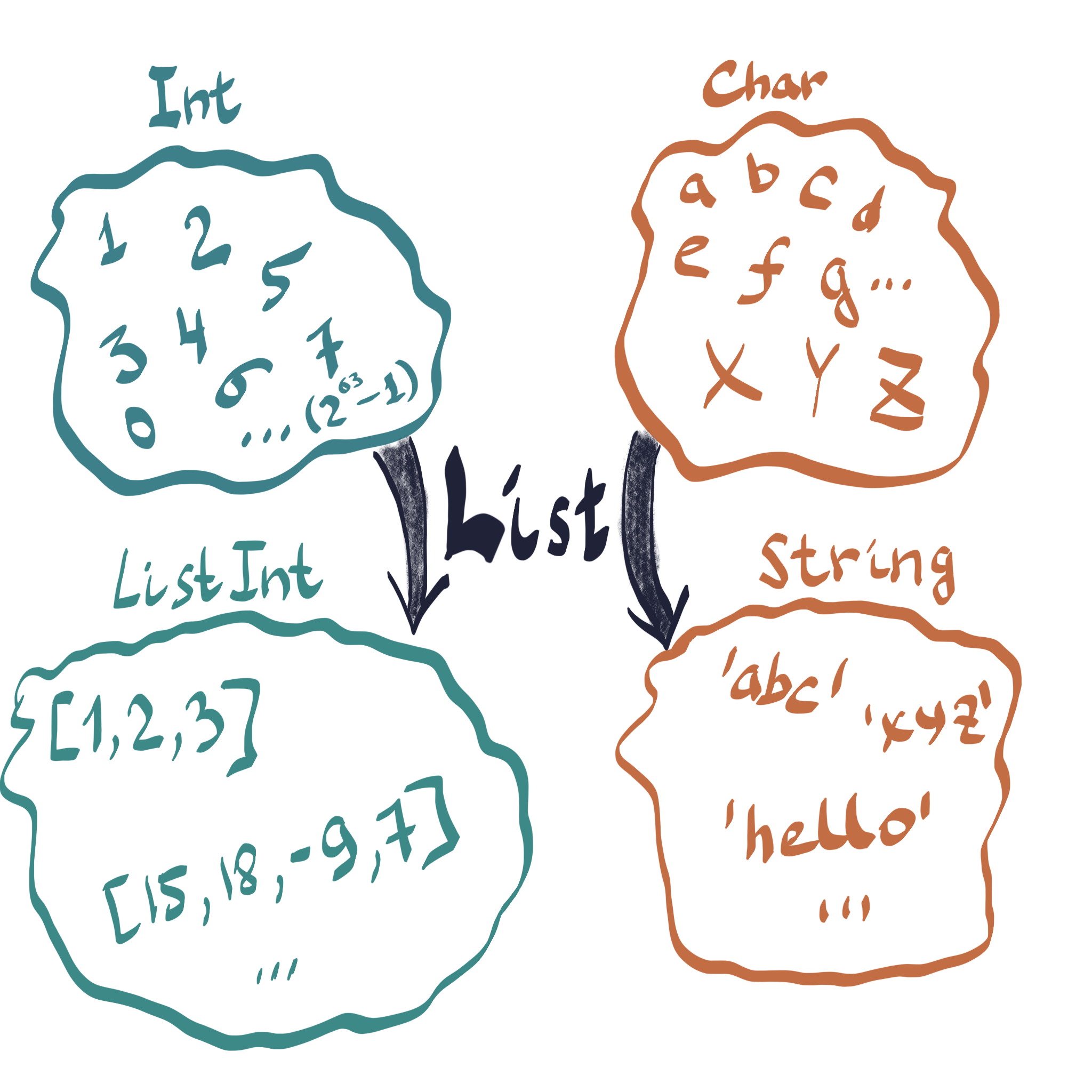

How about “some numbers” type? We can use the same logic as above and introduce the type ListInt - a set of all possible ordered combinations of numbers from Int - such as [1, 2, 3] or [10, 500, 42, -18]. What if we treat each string as a sentence and want to define a type Book that would contain a bunch of sentences together? Again, we can define it as a set of all possible ordered combinations of strings from String.

Do you notice a pattern? We take a type, apply some manipulation we describe as “a set of all possible ordered combinations” to members of this type, and get a new type as a result. Doesn’t it look just like a function?!

Let’s call it List. Just like we have defined functions whichNumberIsChar :: Char -> Int and length :: String -> Int, List is also indeed a function, one that takes a Type and creates a different Type! In Haskell, we write List :: * -> * (‘*’ is a synonym for concrete Type in Haskell). They are sometimes more formally called type level functions and they are the core of the beauty, elegance, and efficiency of Haskell. We will be doing a lot of type creating down the line!

Curry and Recurse!

We saw that a function takes one argument of one type and maps it to exactly one value of another or the same type. A couple of questions should arise at this point:

- what do we do with functions of several arguments that exist even in math – like

f(x,y) = x + y, – not just C-land programming languages, and - how do we actually define functions without resorting to writing explicit tables that map arguments to results, something like “1 + 1 = 2, 0 + 1 = 1, 1 + 0 = 1..” etc for all numbers. You could certainly do that, but it’s a bit unpractical, where by “unpractical” I mean totally nuts.

There are a couple of ways to tackle the first one. Let’s say we want a function that takes a Char and an Int, converts a character to a number with the help of our whichNumberIsChar function and calculates the sum of the two, something like anotherWeirdFunction c i = (whichNumberIsChar c) + i – but we can’t do this since the functions we defined take only one argument! One way to work around it would be to somehow combine our Char and an Int into a new type of pairs (Int, Char) – similar to what we have done with List above – and write:

1 anotherWeirdFunction :: (Char, Int) -> Int

2 anotherWeirdFunction (c, i) = (whichNumberIsChar c) + i

Now we are ok - our function takes just one argument. This is a perfectly valid way to do it, and we will see how to construct pairs from other types in the next chapter. However, it turns out it is much more powerful to use a different approach. First, one very important point:

Functions are first-class citizens in functional programming (that’s kind of why it’s called functional programming) - which means you can pass a function to another function as an argument and return a different function as a result.

Let’s say you want to take a ListInt we defined above and multiply all its elements by some number n. In the imperative world, you would write a function that takes a list and a number n, goes through some cycle, and multiplies it. An ok approach; but what if later on you’d need to add a number n to all list elements? You’d need to write a different cycle that now adds numbers. Wouldn’t it be great if we could just pass a function that we want to apply to all list elements, whatever it is? In Haskell, you can, by simply writing:

1 map (*2) [1,2,3]

2 => [2,4,6]

3 map (+2) [0,8,18]

4 => [2, 10, 20]

We pass a function that adds 2 - (+2) - or multiplies by 2 - (*2) - and a ListInt to a function called map (we will define it in the next chapter), and get another list as a result. Much more concise and powerful than writing a lot of boilerplate imperative cycles, and also hints at how we can define functions of multiple arguments by looking at some further examples:

-

(+) x yis a function of one argument that takes an Int and returns a new function that takes an Int and returns an Int. So,(+2)is a function that adds 2 to any number,(+18)adds 18 etc - and we create these functions on the fly by passing only 1 argument to (+) first. So, the type signature of (+) is:(+) :: Int -> Int -> Int, which you can read as(+) :: Int -> (Int -> Int), i.e. exactly what we just wrote - it takes an Int and returns a function that converts Int to Int! - Our

anotherWeirdFunctionis defined similarly: it’s a function of one argument that takes a Char and returns a function of one argument that takes an Int and returns an Int:

1 anotherWeirdFunction :: Char -> Int -> Int

2 anotherWeirdFunction c i = (whichNumberIsChar c) + i

So, in general, function of many arguments can be defined as a function that takes 1 argument and returns a function that takes 1 argument and returns a function… etc. This technique is called currying, because that’s how you make chicken curry. No, not really. It was invented by Haskell Curry, in whose name both the currying and the Haskell language itself was named.

Currying is extremely useful, because it makes the math much simpler and allows you to create different functions on the fly and pass them around as you see fit. If you want to dig into details, there’s a special optional chapter on Lambda Calculus - it’s quite educational if you want to look into internal machinery of pretty much any modern functional language.

Now, let’s turn to the second question - how to construct functions efficiently.

It is in fact possible to start with an empty set and define all of Haskell - first, you construct natural numbers starting with an empty set as we showed in an aside above, then you can define operation of addition on these numbers, invent integers once you realize you need negative numbers, then define multiplication via addition etc. It is a long and winding road.

We won’t be doing that (although it’s a pretty cool exercise to do on your own after you read the Lambda Calculus chapter) - since existing computer architectures provide a bunch of operations, such as addition, multiplication and memory manipulation for us much more efficiently than if we were to implement them from scratch by translating pure functional lambda calculus logic. Haskell additionally defines a bunch of so called primops, or primitive operations, on top of those, and then a bunch of useful functions in its’ standard library called Prelude - so you can obviously use all of them when writing your functions and do things like:

1 square x = x * x

2 polynom2 x y = square x + 2 * y * x + y

Having said that, a very important concept in functional programming that we need to understand is recursion. It allows you to write concise code for some pretty complex concepts. Let’s start with “hello world” of functional programming - factorial function. Factorial of a number n is defined simply as a product of all numbers from 1 to n, and in Haskell you can in fact simply write product [1..n] - but it’s too easy, so let’s create our factorial function recursively:

1 fact :: Int -> Int -> Int

2 fact n = if n == 0 then 1 else n * fact (n - 1)

What’s happening in recursion is that a function calls itself under certain conditions - in the case of fact, when n > 0. Try executing fact function on the piece of paper with different arguments. E.g., if we call fact 1 here’s what’s going to happen:

1 [1] fact 1

2 [2] if 1 == 0 then 1 else 1 * fact (1 - 1)

3 [3] if False then 1 else 1 * fact 0

4 [4] 1 * fact 0

5 [5] 1 * (if 0 == 0 then 1 else 0 * fact (0 - 1))

6 [6] 1 * (if True then 1 else ...)

7 [7] 1 * 1

8 [8] 1

Phew. Now try expanding fact 10 on paper when you have half an hour to waste. There’s nothing complex about recursion - you (or a computer) simply substitutes function call to the function’s body as normal, and the main thing to remember is that your recursion needs to terminate at some point. That’s why you need boundary cases, such as fact 0 = 1 in the case of factorial, but it can be completely different conditions in other functions.

That’s in essence all there’s to it.

Conclusion

In a very short time, starting with barely anything but an empty set, we have come up with the concepts of:

- Types, inhabited by their members, also called values, and introduced two very simple types: Int and Char

- Functions, which map values of one type to values of another (or the same) type

- Type Functions, which create new types from other types, and introduced a couple of useful complex types: String and ListInt

- Composition, an essence of a functional program (and, incidentally, Category Theory, but we won’t be going there for quite some time yet)

- Ways to construct functions via currying and recursion

This is pretty much everything we need to gradually build our magical Hask world!

What is currently missing is details on how exactly we can define and use functions such as length, that give us the length of a String (or, as we have seen above, any other Type constructed with the help of our List type function!) and List, that creates new types. We can’t just tell a computer “give me a set of all possible combinations” - we need to be slightly more specific. In the next chapter, we will continue following the adventures of our mage and will focus on card magic, while constructing different types and intimately understanding their internal structure - which is an absolute requirement for designing efficient functions.

Let’s roll up our sleeves and get to it!

Mage’s Toolbox 1: Simple Types, Simple Functions, Recursion, If-Else

Download and install haskell from http://haskell.org or via package system on your OS. Run ghci to work with repl, or use online repl.

Type names and Type Constructor names always start with a capital letter.

Functions are defined as:

1 -- type signature first: a function converting Int to Int

2 fact :: Int -> Int

3 -- recursive definition via if-then-else statement:

4 fact n = if n == 0 then 1 else n * fact (n-1)

5 -- no need for parenthesis or comas between function arguments

Definition via pattern matching:

1 fact :: Int -> Int

2 fact 0 = 1

3 fact n = n * fact (n - 1)

4 -- patterns are translated into nested case statements inside the hood, in order

5

6 -- fibonacci numbers:

7 fib :: Int -> Int

8 fib 0 = 1

9 fib 1 = 1

10 fib n = fib (n - 1) + fib (n - 2)

Functions of many arguments defined via currying - as a function of one argument that returns a function of one argument that returns a function…:

1 -- function that takes a Char and an Int and returns an int,

2 -- is really a function that takes a Char and returns a function

3 -- that takes an Int and returns an Int

4 anotherWeirdFunction :: Char -> Int -> Int

5 anotherWeirdFunction c i = (whichNumberIsChar c) + i

6

7 -- useless 3 argument multiplication function:

8 mult3 :: Double -> Double -> Double -> Double

9 mult3 x y z = x * y * z