Linux Commands

<<[../../jelinux/manuscript/passwd.md]

apt-get

The apt-get command is a program, that is used with Debian based Linux distributions to install, remove or upgrade software packages. It’s a vital tool for installing and managing software and should be used on a regular basis to ensure that software is up to date and security patching requirements are met.

There are a plethora of uses for apt-get, but we will consider the basics that will allow us to get by. These will include;

- Updating the database of available applications (

apt-get update) - Upgrading the applications on the system (

apt-get upgrade) - Installing an application (

apt-get install *package-name*) - Un-installing an application (

apt-get remove *package-name*)

The apt-get command

The apt part of apt-get stands for ‘advanced packaging tool’. The program is a process for managing software packages installed on Linux machines, or more specifically Debian based Linux machines (Since those based on ‘redhat’ typically use their rpm (red hat package management (or more lately the recursively named ‘rpm package management’) system). As Raspbian is based on Debian, so the examples we will be using are based on apt-get.

APT simplifies the process of managing software on Unix-like computer systems by automating the retrieval, configuration and installation of software packages. This was historically a process best described as ‘dependency hell’ where the requirements for different packages could mean a manual installation of a simple software application could lead a user into a sink-hole of despair.

In common apt-get usage we will be prefixing the command with sudo to give ourselves the appropriate permissions;

apt-get update

This will resynchronize our local list of packages files, updating information about new and recently changed packages. If an apt-get upgrade (see below) is planned, an apt-get update should always be performed first.

Once the command is executed, the computer will delve into the internet to source the lists of current packages and download them so that we will see a list of software sources similar to the following appear;

[490 B]

Get:2 http://archive.raspberrypi.org wheezy Release.gpg [473 B]

Hit http://raspberrypi.collabora.com wheezy Release

Get:3 http://mirrordirector.raspbian.org wheezy Release [14.4 kB]

Get:4 http://archive.raspberrypi.org wheezy Release [17.6 kB]

Hit http://raspberrypi.collabora.com wheezy/rpi armhf Packages

Get:5 http://mirrordirector.raspbian.org wheezy/main armhf Packages [6,904 kB]

Get:6 http://archive.raspberrypi.org wheezy/main armhf Packages [130 kB]

Ign http://raspberrypi.collabora.com wheezy/rpi Translation-en

Ign http://mirrordirector.raspbian.org wheezy/contrib Translation-en

Ign http://mirrordirector.raspbian.org wheezy/main Translation-en

Ign http://mirrordirector.raspbian.org wheezy/non-free Translation-en

Ign http://mirrordirector.raspbian.org wheezy/rpi Translation-en

Fetched 7,140 kB in 35s (200 kB/s)

Reading package lists... Done

apt-get upgrade

The apt-get upgrade command will install the newest versions of all packages currently installed on the system. If a package is currently installed and a new version is available, it will be retrieved and upgraded. Any new versions of current packages that cannot be upgraded without changing the install status of another package will be left as they are.

As mentioned above, an apt-get update should always be performed first so that apt-get upgrade knows which new versions of packages are available.

Once the command is executed, the computer will consider its installed applications against the databases list of the most up to date packages and it will prompt us with a message that will let us know how many packages are available for upgrade, how much data will need to be downloaded and what impact this will have on our local storage. At this point we get to decide whether or not we want to continue;

6 upgraded, 0 newly installed, 0 to remove and 0 not upgraded.

Need to get 10.7 MB of archives.

After this operation, 556 kB disk space will be freed.

Do you want to continue [Y/n]?

Once we say yes (‘Y’) the upgrade kicks off and we will see a list of the packages as they are downloaded unpacked and installed (what follows is an edited example);

continue [Y/n]? y

Get:1 http://archive.raspberrypi.org/debian/wheezy/main libsdl1.2debian

armhf 1.2.15-5+rpi1 [205 kB]

Get:2 http://archive.raspberrypi.org/debian/wheezy/main raspi-config all

20150131-5 [13.3 kB]

Get:3 http://mirrordirector.raspbian.org/raspbian/ wheezy/main libsqlite3-0

armhf 3.7.13-1+deb7u2 [414 kB]

Fetched 10.7 MB in 31s (343 kB/s)

Preconfiguring packages ...

(Reading database ... 80703 files and directories currently installed.)

Preparing to replace cups-common 1.5.3-5+deb7u5

(using .../cups-common_1.5.3-5+deb7u6_all.deb) ...

Unpacking replacement cups-common ...

Preparing to replace cups-bsd 1.5.3-5+deb7u5

(using .../cups-bsd_1.5.3-5+deb7u6_armhf.deb) ...

Unpacking replacement cups-bsd ...

Preparing to replace php5-gd 5.4.39-0+deb7u2

(using .../php5-gd_5.4.41-0+deb7u1_armhf.deb) ...

Unpacking replacement php5-gd ...

Processing triggers for man-db ...

Setting up libssl1.0.0:armhf (1.0.1e-2+rvt+deb7u17) ...

Setting up libsqlite3-0:armhf (3.7.13-1+deb7u2) ...

Setting up cups-common (1.5.3-5+deb7u6) ...

Setting up cups-client (1.5.3-5+deb7u6) ...

There can often be alerts as the process identifies different issues that it thinks the system might strike (different aliases, runtime levels or missing fully qualified domain names). This is not necessarily a sign of problems so much as an indication that the process had to take certain configurations into account when upgrading and these are worth noting. Whenever there is any doubt about what has occurred, Google will be your friend :-).

apt-get install

The apt-get install command installs or upgrades one (or more) packages. All additional (dependency) packages required will also be retrieved and installed.

If we want to install multiple packages we can simply list each package separated by a space after the command as follows;

apt-get remove

The apt-get remove command removes one (or more) packages.

Test yourself

- How could you install a range of packages with similar names (for example all packages starting with ‘mysql’)?

- When removing a package, is the configuration for that package retained or deleted (Google will be your friend)?

- How could you remove multiple packages with a single command?

cd

The cd command is used to move around in the directory structure of the file system (change directory). It is one of the fundamental commands for navigating the Linux directory structure.

cd [options] directory : Used to change the current directory.

For example, when we first log into the Raspberry Pi as the ‘pi’ user we will find ourselves in the /home/pi directory. If we wanted to change into the /home directory (go up a level) we could use the command;

Take some time to get familiar with the concept of moving around the directory structure from the command line as it is an important skill to establish early in Linux.

The cd command

The cd command will be one of the first commands that someone starting with Linux will use. It is used to move around in the directory structure of the file system (hence cd = change directory). It only has two options and these are seldom used. The arguments consist of pointing to the directory that we want to go to and these can be absolute or relative paths.

The cd command can be used without options or arguments. In this case it returns us to our home directory as specified in the /etc/passwd file.

If we cd into any random directory (try cd /var) we can then run cd by itself;

… and in the case of a vanilla installation of Raspbian, we will change to the /home/pi directory;

cd /var

pi@raspberrypi /var $ cd

pi@raspberrypi ~ $ pwd

/home/pi

In the example above, we changed to /var and then ran the cd command by itself and then we ran the pwd command which showed us that the present working directory is /home/pi. This is the Raspbian default home directory for the pi user.

Options

As mentioned, there are only two options available to use with the cd command. This is -P which instructs cd to use the physical directory structure instead of following symbolic links and the -L option which forces symbolic links to be followed.

For those beginning Linux, there is little likelihood of using either of these two options in the immediate future and I suggest that you use your valuable memory to remember other Linux stuff.

Arguments

As mentioned earlier, the default argument (if none is included) is to return to the users home directory as specified in the /etc/passwd file.

When specifying a directory we can do this by absolute or relative addressing. So if we started in the /home/pi directory, we could go the /home directory by executing;

… or using relative addressing and we can use the .. symbols to designate the parent directory;

Once in the /home directory, we can change into the /home/pi/Desktop directory using relative addressing as follows;

We can also use the - argument to navigate to the previous directory we were in.

Examples

Change into the root (/) directory;

Test yourself

- Having just changed from the

/home/pidirectory to the/homedirectory, what are the five variations of using thecdcommand that will take the pi user to the/home/pidirectory - Starting in the

/home/pidirectory and using only relative addressing, usecdto change into the/vardirectory.

groupadd

The groupadd command is used by a superuser (typically via sudo) to add a group account. It’s a fundamental command in the sense that Linux as a complex multi user system required a mechanism for adding groups. Not that this command will get used every day, but it’s important to know to enable us to administer users on the computer.

-

groupadd[options] group : add a group account

The following example is the simplest application of the command;

This creates the group ‘pigroup’ using the default values from the system.

The groupadd command

The groupadd command is not utilised on a regular basis but it is useful to recognise its role. It adds a group account using the default values from the system. The new group will be entered into the system files as needed.. It can only be used by the root user, so it is often prefixed by the sudo command. Group names may only be up to 32 characters long and if the group name already exists in an external group database such as NIS or LDAP, groupadd will deny the group creation request.

When groupadd is executed it does so utilising the following files;

-

/etc/group: Group account information. -

/etc/gshadow: Secure group account information. -

/etc/login.defs: Shadow password suite configuration.

Test yourself

- What other command that we have looked at utilises the files above?

ifconfig

The ifconfig command can be used to view the configuration of, or to configure a network interface. Networking is a fundamental function of modern computers. ifconfig allows us to configure the network interfaces to allow that connection.

-

ifconfig[arguments] [interface]

or

-

ifconfig[arguments] interface [options]

Used with no ‘interface’ declared ifconfig will display information about all the operational network interfaces. For example running;

… produces something similar to the following on a simple Raspberry Pi.

(0.0 B) TX bytes:0 (0.0 B)

lo Link encap:Local Loopback

inet addr:127.0.0.1 Mask:255.0.0.0

UP LOOPBACK RUNNING MTU:65536 Metric:1

RX packets:0 errors:0 dropped:0 overruns:0 frame:0

TX packets:0 errors:0 dropped:0 overruns:0 carrier:0

collisions:0 txqueuelen:0

RX bytes:0 (0.0 B) TX bytes:0 (0.0 B)

wlan0 Link encap:Ethernet HWaddr 09:87:65:54:43:32

inet addr:10.1.1.8 Bcast:10.1.1.255 Mask:255.255.255.0

UP BROADCAST RUNNING MULTICAST MTU:1500 Metric:1

RX packets:3978 errors:0 dropped:898 overruns:0 frame:0

TX packets:347 errors:0 dropped:0 overruns:0 carrier:0

collisions:0 txqueuelen:1000

RX bytes:859773 (839.6 KiB) TX bytes:39625 (38.6 KiB)

The output above is broken into three sections; eth0, lo and wlan0.

-

eth0is the first Ethernet interface and in our case represents the RJ45 network port on the Raspberry Pi (in this specific case on a B+ model). If we had more than one Ethernet interface, they would be namedeth1,eth2, etc. -

lois the loopback interface. This is a special network interface that the system uses to communicate with itself. You can notice that it has the IP address 127.0.0.1 assigned to it. This is described as designating the ‘localhost’. -

wlan0is the name of the first wireless network interface on the computer. This reflects a wireless interface (if installed). Any additional wireless interfaces would be namedwlan1,wlan2, etc.

The ifconfig command

The ifconfig command is used to read and manage a servers network interface configuration (hence ifconfig = interface configuration).

We can use the ifconfig command to display the current network configuration information, set up an ip address, netmask or broadcast address on an network interface, create an alias for network interface, set up hardware addresses and enable or disable network interfaces.

To view the details of a specific interface we can specify that interface as an argument;

Which will produce something similar to the following;

(8.4 MiB) TX bytes:879127 (858.5 KiB)

The configuration details being displayed above can be interpreted as follows;

-

Link encap:Ethernet- This tells us that the interface is an Ethernet related device. -

HWaddr b8:27:eb:2c:bc:62- This is the hardware address or Media Access Control (MAC) address which is unique to each Ethernet card. Kind of like a serial number. -

inet addr:10.1.1.8- indicates the interfaces IP address. -

Bcast:10.1.1.255- denotes the interfaces broadcast address -

Mask:255.255.255.0- is the network mask for that interface. -

UP- Indicates that the kernel modules for the Ethernet interface have been loaded. -

BROADCAST- Tells us that the Ethernet device supports broadcasting (used to obtain IP address via DHCP). -

RUNNING- Lets us know that the interface is ready to accept data. -

MULTICAST- Indicates that the Ethernet interface supports multicasting. -

MTU:1500- Short for for Maximum Transmission Unit is the size of each packet received by the Ethernet card. -

Metric:1- The value for the Metric of an interface decides the priority of the device (to designate which of more than one devices should be used for routing packets). -

RX packets:119833 errors:0 dropped:0 overruns:0 frame:0andTX packets:8279 errors:0 dropped:0 overruns:0 carrier:0- Show the total number of packets received and transmitted with their respective errors, number of dropped packets and overruns respectively. -

collisions:0- Shows the number of packets which are colliding while traversing the network. -

txqueuelen:1000- Tells us the length of the transmit queue of the device. -

RX bytes:8895891 (8.4 MiB)andTX bytes:879127 (858.5 KiB)- Indicates the total amount of data that has passed through the Ethernet interface in transmit and receive.

Options

The main option that would be used with ifconfig is -a which will will display all of the interfaces on the interfaces available (ones that are ‘up’ (active) and ‘down’ (shut down). The default use of the ifconfig command without any arguments or options will display only the active interfaces.

Arguments

We can disable an interface (turn it down) by specifying the interface name and using the suffix ‘down’ as follows;

Or we can make it active (bring it up) by specifying the interface name and using the suffix ‘up’ as follows;

To assign a IP address to a specific interface we can specify the interface name and use the IP address as the suffix;

To add a netmask to a a specific interface we can specify the interface name and use the netmask argument followed by the netmask value;

To assign an IP address and a netmask at the same time we can combine the arguments into the same command;

Test yourself

- List all the network interfaces on your server.

- Why might it be a bad idea to turn down a network interface while working on a server remotely?

- Display the information about a specific interface, turn it down, display the information about it again then turn it up. What differences do you see?

ln

The ln command is used to make links between files. This allows us to have a single file or directory referred to by different names.

-

ln[options] originalfile linkfile : Create links between files or directories -

ln[options] originalfile : Create a link to the original file in the current directory

The ln command will create a hard link by default and a soft link (symlink) by using the -s option.

For example to create a hard link in the folder /home/pi/foobar/ to the file foo.txt which is in /home/pi/ we could use;

The target directory for the new link must exist for the command to be successful.

Once the link is created if we were to edit the file from either location it will be the same file that is being changed.

The ln command

The ln command is used to make links between files (hence ln = link). By default the links will be ‘hard’ meaning that the links point to the same inode and therefore are pointing to the same data on the hard drive. By using the -s option a soft link (also known as a symbolic link or a symlink) can be created. A soft link has it’s own inode and can span partitions.

This allows us to have a single file of directory referred to by different names.

Hard links

- Will only link to a file (no directories)

- Will not link to a file on a different hard drive / partition

- Will link to a file even when it is moved

- Links to an inode and a physical location on the disk

Soft links (or symbolic links or symlinks)

- Will link to directories or files

- Will link to a file or directory on a different hard drive / partition

- Links will remain if the original file is deleted

- Links will not connect to the file if it is moved

- Links connect via abstract (hence symbolic) conventions, not physical locations on the disk. They have their own inode

Options

There are several different options, but the main one that will be used the most is the -s option to create a soft link.

If we repeat our example from earlier where we wanted to create a link in the folder /home/pi/foobar/ to the file foo.txt which is in /home/pi/, by including the -s option we can make the link soft instead;

If we then list the contents of the foobar directory we will see the following;

1 pi pi 16 Aug 16 01:30 foo.txt -> /home/pi/foo.txt

The read/write/execute descriptors for the permissions are prefixed by an l (for link) and there is a stylised arrow (->) linking the files.

Test yourself

- Can the ‘root’ user create a hard link for a directory?

- What command would be used to create links for multiple ‘txt’ files at the same time?

mv

The mv command is used to rename and move files or directories. It is one of the basic Linux commands that allow for management of files from the command line.

-

mv[options] source destination : Move and/or rename files and directories

For example: to rename the file foo.txt and to call it foo-2.txt we would enter the following;

This makes the assumption that we are in the same directory as the file foo.txt, but even if we weren’t we could explicitly name the file with the directory structure and thereby not just rename the file, but move it somewhere different;

To move the file without renaming it we would simply omit the new name at the destination as so;

The mv command

The mv command is used to move or rename files and directories (mv is an abbreviated form of the word move). This is a similar command to the cp (copy) command but it does not create a duplicate of the files it is acting on.

If we want to move multiple files, we can put them on the same line separated by spaces.

The normal set of wildcards and addressing options are available to make the process more flexible and extensible.

Options

While there are a few options available for the mv command the one most commonly ones used would be -u and -i.

-

uThis updates moved files by only moving the file when the source file is newer than the destination file or when the destination file does not exist. -

iInitiates an interactive mode where we are prompted for confirmation whenever the move would overwrite an existing target.

Examples

To move all the files from directory1 to directory2 (directory2 must initially exist);

To rename a directory from directory1 to directory2 (directory2 must not already exist);

To move the files foo.txt and bar.txt to the directory foobar;

To move all the ‘txt’ files from the users home directory to a directory called backup but to only do so if the file being moved is newer than the destination file;

Test yourself

- How can we move a file to a new location when that act might overwrite an already existing file?

- What characters cannot be used when naming directories or files?

passwd

The passwd command is a vital system administrator tool to manage the passwords for user accounts. We can change our own account, or as the root user we can change other accounts.

-

passwd[options] username : change the user password

To change the current user account all we need to do is execute the passwd command;

To allow our password to be changed, first we need to enter the password we’re going to change;

The we enter the new password;

Then we enter the new password again to confirm that we typed it right the first time;

Then we’re told that the update has been successful;

This is one of the simplest tasks using the passwd command, but there are others that engage a greater degree of complexity for user and password management.

The passwd command

The passwd command allows us to change passwords for user accounts. As a normal user we can only change the password for our own account, while as the superuser (‘root’) we can change the password for any account. The passwd command can also change the properties of an accounts password via options such as;

-

-n: set the minimum number of days between password changes -

-x: set the maximum number of days a password remains valid -

-w: Set the number of days of warning before a password change is required

To view the properties for our password we can use the chage command with the -l option to list the details of the user ‘newpi’s’ password;

This will show us details similar to the following;

We can set the minimum number of days between password changes (via -n), the maximum number of days a password remains valid (via -x) or the number of days of warning before a password change is required (via -w) as follows;

The other administrative functions revolve around administration of other users passwords via the following options;

-

l: locking a users passwordsudo passwd -l newpi -

u: unlocking a users passwordsudo passwd -u newpi(the password used previous to locking is available again) -

e: expire a users passwordsudo passwd -l newpi(forces them to change their password at next login)

Test yourself

- Can you change your own number of days of warning before a password change if you aren’t on the sudo-ers list?

- What is the maximum number of days between a password change?

ssh

The ssh command is used to securely access a remote machine so that a user can log on and execute commands. In spite of its significance, the ssh command is simple to use and is a vital tool for managing computers that are connected on a network. In situations where a computer is running ‘headless’ (without a screen or keyboard) it is especially useful.

-

ssh[options] [login name] server : securely access a remote computer.

For example, operating as the user ‘pi’ we want to login to the computer at the network address 10.1.1.33

We initiate the process by running the command;

If we have never tried to securely login to that computer before, we are presented with a warning asking if we’re sure and is this actually the computer we’re intending to login to;

Assuming that this is correct we can respond with ‘y’ and the process will continue and will ask for the password for the ‘pi’ user (since we executed the command as ‘pi’, the default action is to assume that we are trying to login to the remote computer as the user ‘pi’);

Since we have confirmed this as the correct host it gets added to a master list of know hosts so that we don’t get asked if we know about it in the future. Then we are asked for the ‘pi’ users password on the remote host. Once entered we are logged in and presented with some details of the machine we are connecting to;

At this point we are logged into the computer at 10.1.1.33 and can execute commands as the user ‘pi’ on that machine.

To close this connection we can simply press the key combination CTRL-d and the connection will close with the following message;

The next time we login to the same machine we won’t be asked if we’re sure about the connection and we will be directed straight to the password request.

The ssh command

The ssh command is designed to provide a user with secure access to a shell on a remote computer. There are a number of different ways that users can interact with networked computers, but one of the key functions that needs to be enabled is the ability to execute commands as if you were sitting at a terminal with a keyboard directly attached to the machine.

Often this isn’t possible because the computer is located in another room or even another country. Sometimes the machine has no keyboard or monitor connected and is sitting in a rack or on a shelf. Sometimes the server will be a virtual machine with no ‘real’ hardware at all. For these instances we still want to be able to connect to the machine in some way and execute commands.

There are different commands and programs that will provide this remote access, but one of the increasingly prevailing themes is the need to provide a secure connection between the remote host and the user. This is because control of those remote machines needs to be limited to those who are authorised to carry out work on the machines for the safe operation of the functions they are carrying out (think of remotely controlling an electricity supply or traffic control computers). Without going into the mechanics of it (this would be a book in itself) the ssh command provides a connection between the user and a remote host that has a high degree of security against someone intercepting the information being transmitted.

The example above demonstrated the connection to a remote server as the currently logged in user. However, if we wanted to log in as a different user (let’s call the user ‘newpi’) we would execute the command as follows;

The two examples thus far have used IP addresses to designate the host-name, however, if the remote host had a designated name ‘pinode’ the same command could be entered as follows;

There are a huge number of uses which the ssh command makes possible, but for a new user, the takeaway should be that access between two servers can be carried out easily and the information that is transferred can be done so securely using the ssh command.

Test yourself

- What are the two main functions of the

sshcommand?

sudo

The sudo command allows a user to execute a command as the ‘superuser’ (or as another user). It is a vital tool for system administration and management.

-

sudo[options] [command] : Execute a command as the superuser

For example, if we want to update and upgrade our software packages, we will need to do so as the super user. All we need to do is prefix the command apt-get with sudo as follows;

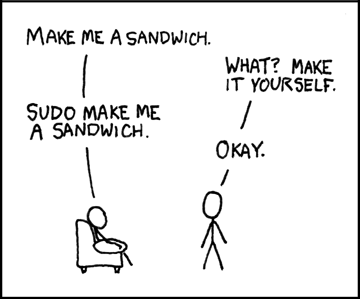

One of the best illustrations of this is via the excellent cartoon work of the xkcd comic strip (Buy his stuff, it’s awesome!).

The sudo command

The sudo command is shorthand for ‘superuser do’.

When we use sudo an authorised user is determined by the contents of the file /etc/sudoers.

As an example of usage we should check out the file /etc/sudoers. If we use the cat command to list the file like so;

We get the following response;

That’s correct, the ‘pi’ user does not have permissions to view the file

Let’s confirm that with ls;

Which will result in the following;

1 root root 696 May 7 10:39 /etc/sudoers

It would appear that only the root user can read the file!

So let’s use sudo to cat the file as follows;

That will result in the following output;

There’s a lot of information in the file, but there, right at the bottom is the line that determines the privileges for the ‘pi’ user;

We can break down what each section means;

pi

pi ALL=(ALL) NOPASSWD: ALL

The pi portion is the user that this particular rule will apply to.

ALL

pi ALL=(ALL) NOPASSWD: ALL

The first ALL portion tells us that the rule applies to all hosts.

ALL

pi ALL=(ALL) NOPASSWD: ALL

The second ALL tells us that the user ‘pi’ can run commands as all users and all groups.

NOPASSWD

pi ALL=(ALL) NOPASSWD: ALL

The NOPASSWD tells us that the user ‘pi’ won’t be asked for their password when executing a command with sudo.

All

pi ALL=(ALL) NOPASSWD: ALL`

The last ALL tells us that the rules on the line apply to all commands.

Under normal situations the use of sudo would require a user to be authorised and then enter their password. By default the Raspbian operating system has the ‘pi’ user configured in the /etc/sudoers file to avoid entering the password every time.

If your curious about what privileges (if any) a user has, we can execute sudo with the -l option to list them;

This will result in output that looks similar to the following;

for pi on this host:

env_reset, mail_badpass,

secure_path=/usr/local/sbin\:/usr/local/bin\:/usr/sbin\:/usr/bin\:/sbin\:/bin

User pi may run the following commands on this host:

(ALL : ALL) ALL

(ALL) NOPASSWD: ALL

The ‘sudoers’ file

As mentioned above, the file that determines permissions for users is /etc/sudoers. DO NOT EDIT THIS BY HAND. Use the visudo command to edit. Of course you will be required to run the command using sudo;

sudo vs su

There is a degree of confusion about the roles of the sudo command vs the su command. While both can be used to gain root privileges, the su command actually switches the user to another user, while sudo only runs the specified command with different privileges. While there will be a degree of debate about their use, it is widely agreed that for simple on-off elevation, sudo is ideal.

Test yourself

- Write an entry for the

sudoersfile that provides sudo privileges to a user for only thecatcommand. - Under what circumstances can you edit the

sudoersfile with a standard text editor.

tar

The tar command is designed to facilitate the creation of an archive of files by combining a range of files and directories into a single file and providing the ability to extract these files again. While tar does not include compression as part of its base function, it is available via an option. tar is a useful program for archiving data and as such forms an important command for good maintenance of files and systems.

-

tar[options] archivename [file(s)] : archive or extract files

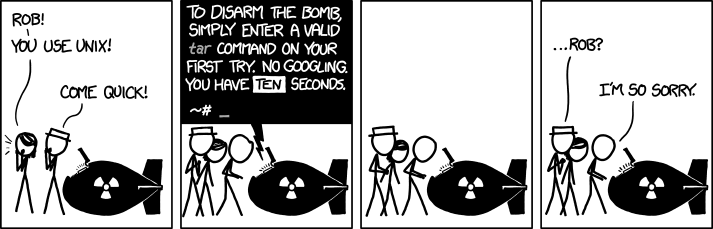

tar is renowned as a command that has a plethora of options and flexibility. So much so that it can appear slightly arcane and (dare I say it) ‘over-flexible’. This has been well illustrated in the excellent cartoon work of the xkcd comic strip (Buy his stuff, it’s awesome!).

However, just because it has a lot of options does not mean that it needs to be difficult to use for a standard set of tasks and at its most basic is the creation of an archive of files as follows;

Here we are creating an archive in a file called foobar.tar of the files foo.txt and bar.txt.

The options used allow us to;

-

c: create a new archive -

v: verbosely list files which are processed. -

f: specify the following name as the archive file name

The output of the command is the echoing of the files that are placed in the archive;

The additional result is the creation of the file containing our archive foobar.tar.

To carry the example through to its logical conclusion we would want to extract the files from the archive as follows;

The options used allow us to;

-

x: extract an archive -

v: verbosely list files which are processed. -

f: specify the following name as the archive file name

The output of the command is the echoing of the files that are extracted from the archive;

The tar command

tape archive, or tar for short, is a command for converting files and directories into a single data file. While originally written for reading and writing from sequential devices such as tape drives, it is nowadays used more commonly as a file archive tool. In this sense it can be considered similar to archiving tools such as WinZip or 7zip. The resulting file created as a result of using the tar command is commonly called a ‘tarball’.

Note that tar does not provide any compression, so in order to reduce the size of a tarball we need to use an external compression utility such as gzip. While this is the most common, any other compression type can be used. These switches are the equivalent of piping the created archive through gzip.

One advantage to using tar over other archiving tools such as zip is that tar is designed to preserve Unix filesystem features such as user and group permissions, access and modification dates, and directory structures.

Another advantage to using tar for compressed archives is the fact that any compression is applied to the tarball in its entirety, rather than individual files within the archive as is the case with zip files. This allows for more efficient compression as the process can take advantage of data redundancy across multiple files.

Options

-

c: Create a new tar archive. -

x: Extract a tar archive. -

f: Work on a file. -

z: Use Gzip compression or decompression when creating or extracting. -

t: List the contents of a tar archive.

The tar program does not compress the files, but it can incorporate the gzip compression via the -z option as follows;

If we want to lit the contents of a tarball without un-archiving it we can use the -t option as follows;

When using tar to distribute files to others it is considered good etiquette to have the tarball extract into a directory of the same name as the tar file itself. This saves the recipient from having a mess of files on their hands when they extract the archive. Think of it the same way as giving your friends a set of books. They would much rather you hand them a box than dump a pile of loose books on the floor.

For example, if you wish to distribute the files in the foodir directory then we would create a tarball from the directory containing these files, rather than the files themselves:

Remember that tar operates recursively by default, so we don’t need to specify all of the files below this directory ourselves.

Test yourself

- Do you need to include the

zoption when decompressing atararchive? - Enter a valid tar command on the first try. No Googling. You have 10 seconds.

useradd

The useradd command is used by a superuser (typically via sudo) to add a user system account. It’s a fundamental command in the sense that Linux as a multi user system required a mechanism for adding users. Not that this command will get used every day, but it’s important to know to enable us to administer users on the computer.

-

useradd[options] username : add a user account

The following example is the simplest application of the command;

This creates the user, but in doing so it is set in a ‘locked’ state because it doesn’t have a password associated with it. This can be set using the passwd command.

The useradd command

The useradd command is not utilised on a regular basis, in fact, the man page for the command recommends using adduser which is a friendlier front end to this low level tool. It adds a user to the list of entities able to access the computer system although used without any options, the command leaves the new account locked until a password is set with passwd. It can only be used by the root user, so it is often prefixed by the sudo command.

Options

There are several useful options that can be used with useradd, but the commonly used ones we will examine are;

-

-m: Add the user’s home directory if it doesn’t exist -

-s: Specify the user’s login shell

To add the home directory for the ‘newpi’ user and set their login shell to bash we would use the following command;

Test yourself

- What is the more user friendly alternative to

useradd?

usermod

The usermod command is used by a superuser (typically via sudo) to change a user’s system account settings. It’s not a command that will get used every day, but it’s important to know that it’s there to enable us to administer user details on the computer.

-

usermod[options] username : Modify a users account configuration

The following example is one used in the early stages of setting up the Raspberry Pi where we want to make our user ‘pi’ a member of the group ‘www-data’ which will allow (in conjunction with other steps) the user to edit the files in a web server;

The -a option adds the user to an additional ‘supplementary’ group (-a must only be used in a situation where it is followed by the use of a -G option). The -G option lists the supplementary group to which a user will be added. In this case the group is www-data. Finally the user which is getting added to the supplementary group is pi.

The usermod command

The usermod command is not utilised on a regular basis, but when required to administer a users administrative details it is useful to know what it is able to do and how to configure the command. It modifies a users settings (hence usermod = user modify) and can be used for such tasks as changing a users home directory, password expiry date, their default shell and the groups that the user belongs to. It can only be used by the root user, so it is often prefixed by the sudo command.

When usermod changes a users settings it does so utilising the following files;

-

/etc/group: Group account information. -

/etc/gshadow: Secure group account information. -

/etc/login.defs: Shadow password suite configuration. -

/etc/passwd: User account information. -

/etc/shadow: Secure user account information.

Options

There are about 15 options that can be used with usermod, but the commonly used ones we will examine are;

-

-d: Change the user’s home directory -

-g: Change the user’s primary group -

-a -Ggroup : Add the user to a supplemental group -

-s: Change the users default shell -

-L: Lock the users account by disabling the password -

-U: Unlock the users account by re-enabling the previous password

To change the home directory for the ‘pi’ user to the directory /home/newpi we would use the following command;

To make ‘pigroup’ the primary group for the user ‘pi’;

Different users will be comfortable in different shells. To change the users default shell we can use the -s option. The following example changes the default shell for the ‘pi’ user to the ‘Korn’ shell;

We can lock a users account using the -L option which modifies the /etc/shadow file by putting an exclamation mark in front of the encrypted password. The following example does this for the ‘pi’ user;

Then we will want to unlock the locked user account with the -U option as follows;

Test yourself

- What might we need to do before changing the primary group of a user to a new group?

- How might we manually unlock a users account without using the

usermodcommand?

wget

The wget command (or perhaps a better description is ‘utility’) is a program designed to make downloading files from the Internet easy using the command line. It supports the HTTP, HTTPS and FTP protocols and is designed to be robust to accomplish its job even on a network connection that is slow or unstable. It is similar in function to curl for retrieving files, but there are some key differences between the two, with the main one for wget being that it is capable of downloading files recursively (where resources are linked from web pages).

-

wget[options] [URL] : download or upload files from the web non-interactivly.

In it’s simplest example of use it is only necessary to provide the URL of the file that is required and the download will begin;

The program will then connect to the remote server, confirm the file details and start downloading the file;

As the downloading process proceeds a simple text animation advises of the progress with an indication of the amount downloaded and the rate

Once complete the successful download will be reported accompanied by some statistics of the transfer;

The file is downloaded into the current working directory.

The wget command

wget is a utility that exists slightly out of the scope of a pure command in the sense that it is an Open Source program that has been complied to work on a range of operating systems. The name is a derivation of web get where the function of the program is to ‘get’ files from the world wide web.

It does this via support for the HTTP, HTTPS and FTP protocols such that if you could paste a URL in a browser and have it subsequently download a file, the same file could be downloaded from the command line using wget. wget is not the only file downloading utility that is commonly used in Linux. curl is also widely used for similar functions. However both programs have different strengths and in the case of wget that strength is in support of recursive downloading where an entire web site could be downloaded while maintaining its directory structure and links. There are other differences as well, but this would be the major one.

There is a large range of options that can be used to ensure that downloads are configured correctly. We will examine a few of the more basic examples below and after that we will check out the recursive function of wget.

-

--limit-rate: limit the download speed / download rate. -

-O: download and store with a different file name -

-b: download in the background -

-i: download multiple files / URLs -

--ftp-userand--ftp-password: FTP download using wget with username and password authentication

Rate limit the bandwidth

There will be times when we will be somewhere that the bandwidth is limited or we want to prioritise the bandwidth in some way. We can restrict the download speed with the option --limit-rate as follows;

Here we’ve limited the download speed to 20 kilo bytes per second. The amount may be expressed in bytes, kilobytes with the k suffix, or megabytes with the m suffix.

Rename the downloaded file

If we try to download a file with the same name into the working directory it will be saved with an incrementing numerical suffix (i.e. .1, .2 etc). However, we can give the file a different name when downloaded using the -O option (that’s a capital ‘o’ by the way). For example to save the file with the name alpha.zip we would do the following;

Download in the background

Because it may take some considerable time to download a file we can tell the process to run in the background which will release the terminal to carry on working. This is accomplished with the -b option as follows;

While the download continues, the progress that would normally be echoed to the screen is passed to the file wget-log that will be in the working directory. We can check this file to determine progress as necessary.

Download multiple files

While we can download multiple files by simply including them one after the other in the command as follows;

While that is good, it can start to get a little confusing if a large number of URL’s are included. To make things easier, we can create a text file with the URL’s/names of the files we want to download and then we specify the file with the -i option.

For example, if we have a file named files.txt in the current working directory that has the following contents;

Then we can run the command…

… and it will work through each file and download it.

Download files that require a username and password

The examples shown thus far have been able to be downloaded without providing any form of authentication (no user / password). However this will be a requirement for some downloads. To include a username and password in the command we include the --ftp-user and --ftp-password options. For example if we needed to use the username ‘adam’ and the password ‘1234’ we would form or command as follows;

You may be thinking to yourself “Is this secure?”. To which the answer should probably be “No”. It is one step above anonymous access, but not a lot more. This is not a method by which things that should remain private should be secured, but it does provide a method of restricting anonymous access.

Download files recursively

One of the main features of wget is it’s ability to download a large complex directory structure that exists on many levels. The best example of this would be the structure of files and directories that exist to make up a web site. While there is a wide range of options that can be passed to make the process work properly in a wide variety of situations, it is still possible to use a fairly generic set to get us going.

For example, to download the contents of the web site at dnoob.runkite.com we can execute the following command;

The options used here do the following;

-

-e robots=off: the execute option allows us to run a separate command and in this case it’s the commandrobots=offwhich tells the web site that we are visiting that it should ignore the fact that we’re running a command that is acting like a robot and to allow us to download the files. -

-r: the recursive option enables recursive downloading. -

-np: the no-parent option makes sure that a recursive retrieval only works on pages that are below the specified directory. -

-c: the continue option ensures that any partially downloaded file continues from the place it left off. -

-nc: the no-clobber option ensures that duplicate files are not overridden

Once entered the program will display a running listing of the progress and a summary telling us how many file and the time taken at the end. The end result is a directory called dnoob.runkite.com in the working directory that has the entire website including all the linked pages and files in it. If we examine the directory structure it will look a little like the following;

Using wget for recursive downloading should be used appropriately. It would be considered poor manners to pillage a web site for anything other than good reason. When in doubt contact the person responsible for a site or a repository just to make sure there isn’t a simpler way that you might be able to accomplish your task if it’s something ‘weird’.

Test yourself

- Craft a

wgetcommand that downloads a file to a different name, limiting the download rate to 10 kilobytes per second and which operates in the background. - Once question 1 above is carried out, where do we find the output of the downloads progress?