III. Fundamentals of Effective Documentation

When designing and implementing complex systems, it is very helpful to distinguish between requirements (the problem) and the solution. When you improve your understanding of the problem, you can align the solution way better to these requirements.

Let’s begin by discussing the requirements to technical documentation and communication, independent of arc42. Afterwards we’ll present numerous pragmatic tips how you can create effective documentation simple, fast and with less effort than you ever imagined. Painless, nonviolent, without sophisticated tools or elaborate processes.

III.1 Documentation Requirements

Requirements for technical documentation will come from various stakeholders:

- Consumers (readers), who want to get their specific tasks done with help of the documentation. This group includes software developers, who want to read the documentation to implement new features in their system easily and quickly.

- Producers (authors), who produce and maintain documentation. They want to make changes in the system with minimal effort to update the doucemtation.

The following paragraphs summarize the seven commandments4 or rules for architecture documentation. The rest of the book focusses on how you can achieve these.

Rule 1: Helpful

Rule 1: Helpful

Documentation has to be help all readers to perform their concrete tasks. It should ease or facilitate their work. Therefore the following relation must be true:

Even during system development architecture documentation should be helpful and not be regarded as an unnecessarily burdening extra effort.

Rule 2: Correct

Rule 2: Correct

Incorrect information in (technical) documentation can be as bad as software bugs. Even worse: Readers who find mistakes in one part of the documentation quickly loose their trust in the rest: The perceived value of the documentation vastly decreases.

Therefore, one important requirement for documentation is its correctness: Never (ever!) allow incorrect information in documentation. Correctness is the highest goal that you should never jeopardize!

Rule 3: Current

Rule 3: Current

Correctness of documentation changes over time. What was correct yesterday could already be wrong today. You want your documentation to be current.

Rule 4: Easy to find

A specialization of “easy to use”: Documentation consumers shall be able to find information easily and quickly. Fixed structures (like arc42) and conventions help with that.

Rule 5: Easy to understand

Consumers (readers) have to understand documentation easily. Documentation has to fulfil their expectations in many dimensions: language, notation, form and tooling. Easier said than done - because sometimes the producers of documentation do not (yet) know all consumers that might need that documentation in the future.

Rule 6: Easy to change

Every change (enhancements, reconstructions, maintenance, and even bugfixes) can lead to necessary changes in the documentations. The easier it is for developers to adapt documentation, the higher the chances that the documentation really gets updated.

On the other hand, if changing the documentation is difficult and costly it is simple not done. Documentation then becomes outdated (loosing its correctness).

Many tips in this book address this requirement and show how to improve changeability of documentation.

Rule 7: Adequat

We don’t know how much documentation you really need for your system, how detailed you need it, and which notation you prefer. The stakeholders of your system may have special requirements and wishes concerning documentation based upon their specific tasks and experiences. arc42 suggests a pragmatic structure, but you have to determine the level of detail, adequate notations, and sufficient formalism for your system.

See also section VII.2 on the minimal amount of documentation.

III.2 Fundamental Tips for Documentation

Tip III-1: Appoint a Responsible Person (The Docu-Gardener)

![]() In real life,

gardeners have at least two different tasks: to plant (create new documentation)and to weed

(remove outdated or unnecessary documentation). For (software architecture) documentation your gardener needs to:

In real life,

gardeners have at least two different tasks: to plant (create new documentation)and to weed

(remove outdated or unnecessary documentation). For (software architecture) documentation your gardener needs to:

- care for the adequate form and content and

- proactively search for unnecessary or outdated parts and remove them.

Please note: care does not mean your gardener shall create all content by her- or himself, but identify appropriate producers within the team or among associated stakeholders.

Tip III-2: Document economically (“Less is often more”)

![]() When you create documentation, you implicitly create a mortgage

for future generation: Whenever you modify your system, someone might need to

maintain or adjust the corresponding documentation.

When you create documentation, you implicitly create a mortgage

for future generation: Whenever you modify your system, someone might need to

maintain or adjust the corresponding documentation.

We really believe that documentation can be helpful and ease development work - but only in an extend and degree appropriate for the system and its stakeholders.

Our tips for appropriate (economical or thrifty) documentation:

- Less (shorter) documentation can be often read and digested in shorter time (but beware of overly cryptic brevity, so no Perl, APG or regular expressions).

- Less documentation implies fewer future changes or modifications.

- Explicitly decide what kind and amount of documentation is appropriate, and with what level of detail.

- Differentiate between short-lived, volatile documentation (i.e. flipcharts for your project work) and long-lived system documentation. See [tip V-6]{#tip-v-6}

- Dare to leave gaps: Deliberately leave certain parts of your (arc42) documentation empty. Especially within arc42-section 8 (crosscutting concepts) you can often remove numerous subsections that might not be relevant for your specific system.

Tip III-3: Clarify appropriateness and needs through early feedback

![]() Type, amount and level of details of your

documentation should be appropiate,

Type, amount and level of details of your

documentation should be appropiate,

in relation to the system, the affected people, domain, risks, criticality,

effort/cost and possibly even other factors.

arc42 supports you with suggesting a documentation/communication structure,

but does not suggests a certain form, notation, level of detail or target audience.

What appropriateness means in your specific case and for your system you have to find out for yourself, with help of your stakeholders:

At first, describe only a little part or aspect of your system - and get specific feedback for this documentation from involved stakeholders.

Ask stakeholders:

- What parts of this documentation is helpful?

- Which aspects need improvement? What kind of improvement?

- Which parts of the documentation should we enhance?

- Where can we shorten the documentation?

- Is the way of presenting, level of details and notation appropriate?

- Is the type of output (e.g.: pdf, html, docx, Wiki) acceptable?

- Do we have to document the parameters at the interface X in the architecture, or are the unit-tests enough?

For example, create diagrams in several iterations or refinements: Your first draft can be handwritten and really schematic. Through feedback you should quickly find out, if either your figure actually goes in the right direction (good) - or if your documentation does in no way fulfill the information demand of the stakeholders (bad). This way, you can sort out expectations through feedback. The more concrete you ask affected people for specific feedback and/or points of view, the more concrete their answers will turn out.

Avoid closed questions like “Is the documentation okay this way?” - because neither after a “yes” nor after a “no” you concretely know what to do!

Better ask open questions like “What do we have to change or enhance so that this documentation can support your work better?”

Tip III-4: Communicate top-down, work differently if necessary

Top-down means presenting circumstances starting from a high level of abstraction (few details), stepwise refining up to more details and concretisation. Such top-down communication generally facilitates understanding for all kinds of stakeholders.

On the other hand, a top-down communication structure should never enforce a specific developement method or a specific order of development activities.

Especially during developement it is often more effective to solve problems bottom-up. Communication and documentation of results should nevertheless be organized top-down.

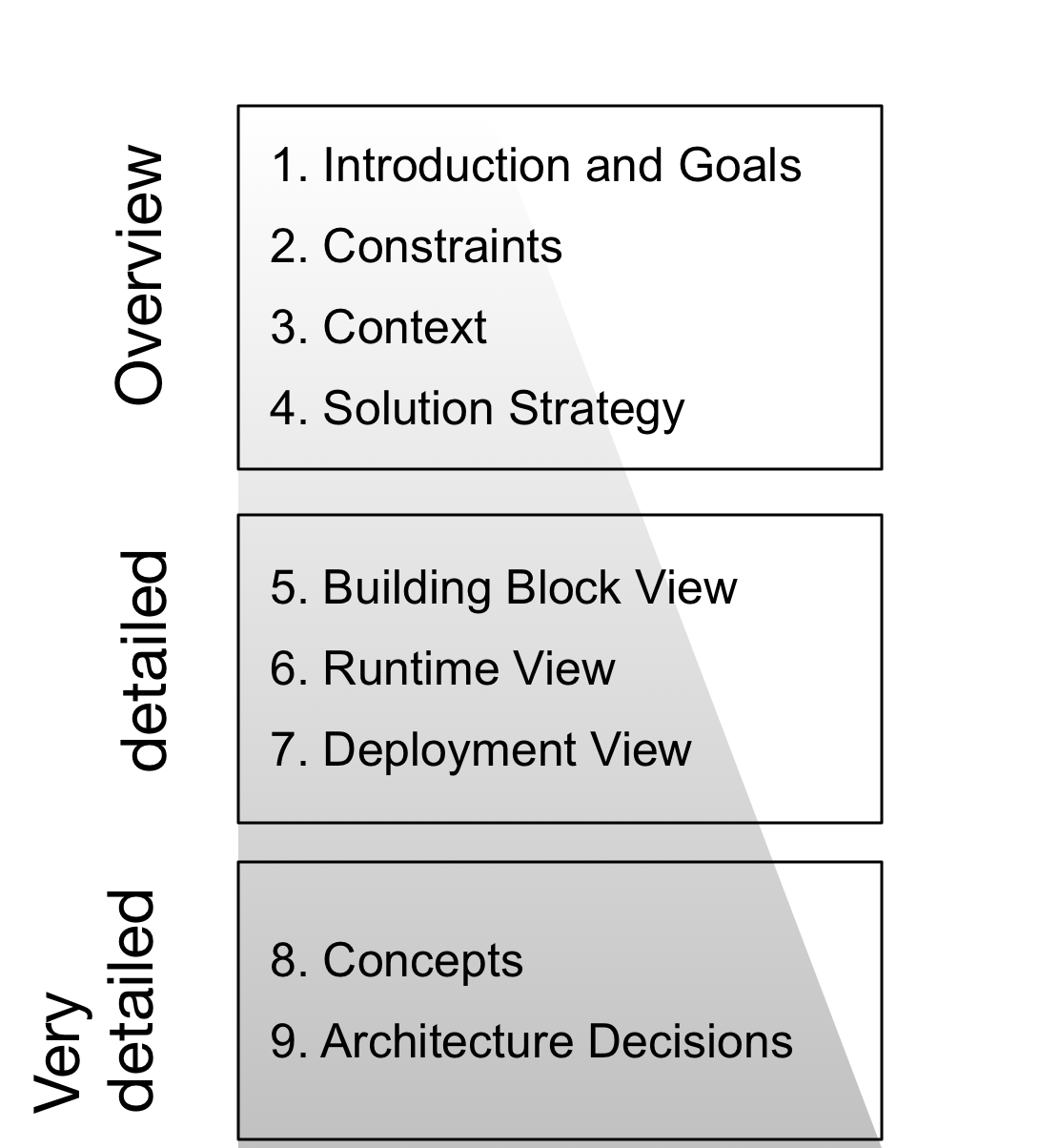

arc42 supports this advice with it’s strict top-down scheme, see figure arc42 top-down.

- arc42 sections 1 & 2 contain the introduction and goals, a brief summary of the systems’ requirements. This is the birds’ eye perspective on the system.

- arc42 section 3 describes the context with the external interfaces. It’s an high-level overview and adds only little detail.

- arc42 section 4, the solution strategy, gives a glimpse into the systems’ most influential decisions, concepts or approaches.

- The building block view in section 5 is inherently organized top-down. It adds an arbitrary amount of detail to describe the how the source code of the system is structured.

- The runtime view in arc42 section 6 shows typical or important scenarios that show how the building blocks interact at runtime.

- Often the crosscutting concepts in arc42 section 8 contain detailed descriptions or specifications how certain recurring problems within the system are solved. Quite often this will be the most detailed part of architecture documentation.

- The decisions in arc42 section 9 might be detailed, although several real-world documentations we encountered remained quite brief here, and instead focussed on the concepts in the preceeding section.

Tip III-5: Focus on Explanation and Rationale, Not Only Facts

Most facts about a software system can be found in its source code - but not their explanation, reasoning and rationale:

- Why is a specific white box structured as it is? Why does it consist of five blackboxes, not seven or eleven?

- Why was this (and not another) library/framework chosen to generate pdf documents?

- Why is one building block deployed on different hardware than all the others?

For arc42 documentation we propose to (briefly) explain at least the whitebox structures of the building block view. Furthermore you should elaborate surprising, special or risky decisions or concepts.

Tip III-6: Rate Requirements Higher than Principles

Specific requirements or goals shall always be more important than generic or global principles - as most of use are valued by reaching our goals, and only very few of for adhering to principles.

You should therefore treat arc42 or similar templates as pragmatic means, and definitely not as strict regulation.

Never treat arc42 as a form (like the yearly income-tax-form), but as a well-formed and prestructured cabinet with drawers (see figure “arc42-metaphor”).

Use these drawers as appropriate in your current and specific situation.

Stefan Zörner calls this approach (in his German book [Zörner-15]): „Use templates pragmatically“.

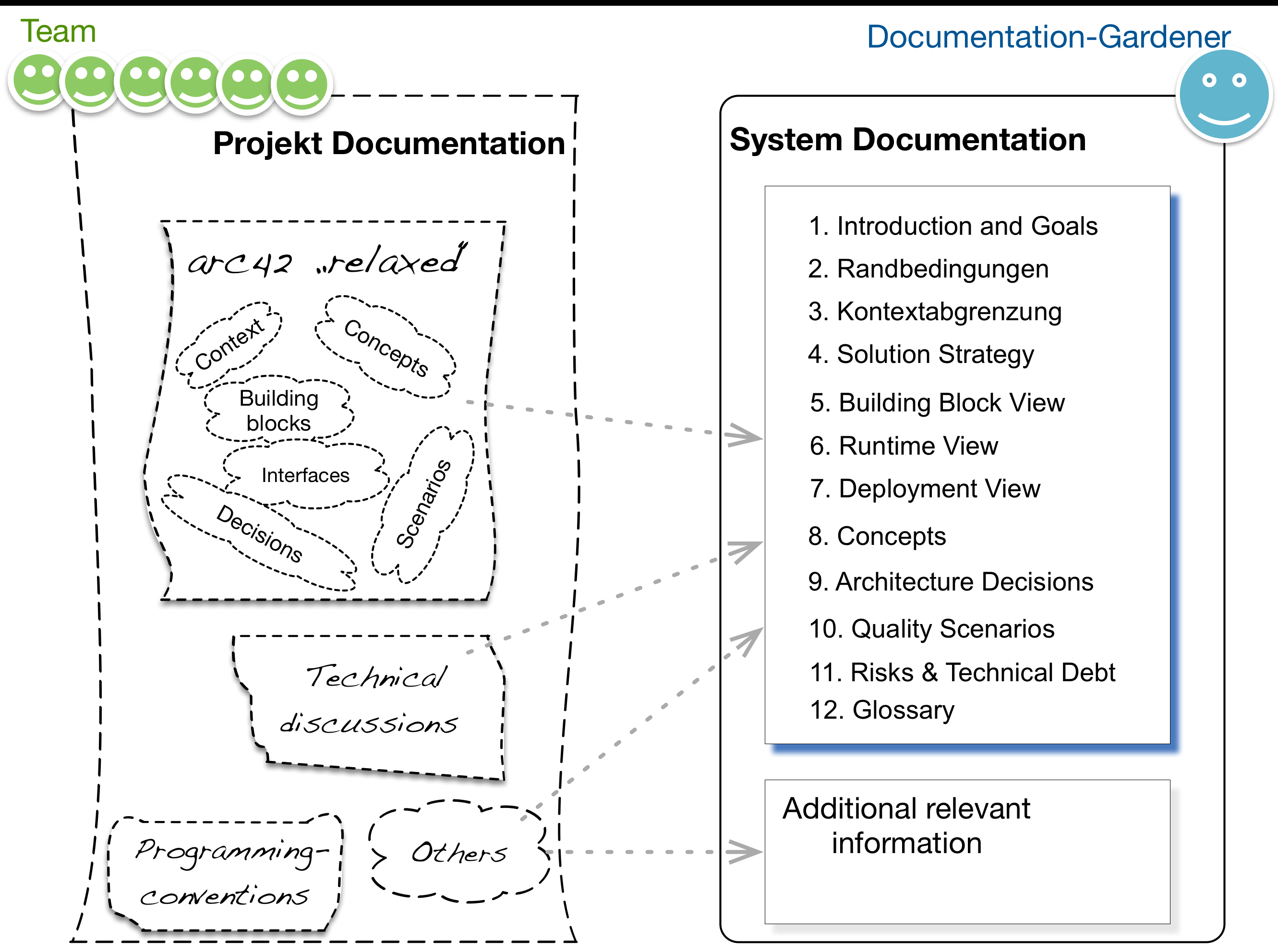

Tip III-7: Separate Volatile and Stable Documentation

We assume that you work in a project (rather short-lived) on a system (rather long-lived):

During development or maintenance of a system the development team needs efficient means for ad-hoc and often short-lived, temporary communication. For such project documentation, refrain from any formal or process requirements, if possible.

- Keep the entrance barrier for (written) communication as low as possible,

- Prefer low-tech tools over sophisticated electronic or online gadgets.

We call such documentation volatile, as teams need it only to support their development work - and many of these topics will not be relevant for the system on the long run.

See also tip V-6.

Eine verantwortliche Person (der Doku-Gärtner aus Tipp 1‑1) sollte diese Struktur (gemäß arc42) festlegen und gemeinsam mit dem Team angemessen mit Inhalt füllen.

Tip III-8: Don’t Repeat Yourself, If Possible

Vermeiden Sie unnötige Wiederholungen. Mehrfache Darstellung identischer Sachverhalte erzeugt überhöhten Pflegeaufwand bei Änderungen, und macht obendrein die Nutzung von Dokumentation schwieriger. Bei Redundanz ist die Chance recht groß, dass Sachverhalte an einer Stelle leicht anders beschrieben werden als an anderen Stellen. Das verwirrt Leser: Sind diese Unterschiede gewollt oder ein Versehen? Auf welche dieser Stellen kann ich mich verlassen, und auf welche eher nicht? Warum schränken wir dann bereits im Namen dieses Tipps auf „falls möglich“ ein, und fordern keine absolute Redundanzfreiheit? Der Grund liegt im Lesekomfort: An manchen Stellen möchten Sie Ihren Lesern Sachverhalte „als Ganzes“ vermitteln. Beispiel: Der arc42-Abschnitt 1 (Einführung und Ziele) erläutert die Anforderungen an das System. Hoffentlich haben Sie die Anforderungen in einem Requirements-Dokument, einem Lastenheft, einer Sammlung von User-Stories oder ähnlicher Dokumentation beschrieben. In der Architekturdokumentation möchten wir die wesentlichen Inhalte dieser Anforderungen komprimiert wiedergeben (Gewollte Redundanz!) – weil wir Lesern komfortabel diesen Extrakt der Anforderungen vorstellen möchten. Würden wir in diesem Abschnitt lediglich Hyperlinks auf andere Dokumente einfügen, wären wir einerseits redundanzfrei, andererseits zwängen wir die Leser dazu, die Informationen an völlig anderer Stelle nachzulesen… Also: Erlauben Sie Redundanz nur dort, wo sie den Lesekomfort oder das Verständnis erhöht.

Tip III-9: Document Unmistakably

Dokumentation sollte von allen Konsumenten gleichermaßen (eindeutig, non-ambiguous) verstanden werden. Nennen Sie gleiche Dinge überall gleich. Unterschiedliche Dinge brauchen unterschiedliche Namen. Eine Spezialisierung dieses Tipps lautet: „Erklären Sie Ihre Notation“: Sorgen Sie dafür, dass alle Beteiligten die verwendeten Notationen kennen. Bei Bedarf verwenden Sie Legenden oder verweisen (im Falle von Standardnotationen wie UML oder ER-Diagrammen) auf die gängige Literatur. Das hört sich vielleicht überflüssig an („ist doch jedem klar, was hier gemeint ist…“) – aber andere Personen könnten Ihre Symbole auf ganz unterschiedliche Arten interpretieren:

Ohne Erklärung der Symbole könnten Foo, Bar und bazz beispielsweise folgende (unterschiedliche) Bedeutung haben: ¥ Vom Hardware-Server Foo fließen bazz-Daten zum DB-Server Bar. ¥ Die fachliche Aktivität Foo sendet einen bazz-Event an den Prozess Bar. ¥ Das Skript Foo startet die Funktion bazz im Modul Bar… ¥ Die Funktion bazz übersetzt Foo in Bar

Sie sehen – ohne weitere Erklärung droht Missverständnis. Agieren Sie in dieser Hinsicht präventiv – und stellen Eindeutigkeit a priori sicher!

Tip III-10: Establish a Positive Documentation Culture

Ensure that documentation is a positive and friendly term within your team. Documentation shall support your stakeholders, never hinder them.

Persisting important architectural decisions, structures or concepts shall be regarded as something good, it’s positive for you and other stakeholders of your system.

For example, incorporate documentation in your Definition-of-Done (DoD), at least in case you’re developing in agile ways (what we really hope for you).

Tip III-11: Create Documentation From The Reader’s Point of View

Erstellen Sie Dokumentation für und aus der Sicht von deren Konsumenten ([Clements-11] nennt das „write documentation from the reader’s point of view“). Nehmen Sie die Stakeholder-Tabelle von arc42 (siehe arc42-Abschnitt 1.3) ernst: Darin sammeln Sie die konkreten Wünsche und Anforderungen Ihrer Stakeholder an das System und dessen Dokumentation!