A Technical Introduction to Model Context Protocol and Experiments with LM Studio

Here I will guide you, dear reader, through the process of using the Model Context Protocol (MCP). This is a long chapter. We will start with some background material and then work through a few examples that you can easily modify for your own applications.

An Introduction to the Model Context Protocol

The rapid evolution of Large Language Models (LLMs) has shifted the focus of AI development from model creation to model application. The primary challenge in this new era is no longer just generating coherent text, images, and videos, but also enabling LLMs to perceive, reason about, and act upon the world through external data and software tools. Here we learn a definitive architectural guide to the MCP, an open standard designed to solve this integration challenge. We study a complete strategy for leveraging MCP within a local, privacy-centric environment using LM Studio, culminating in an example Python implementation of a custom MCP compatible services that interact with models running on LM Studio.

The Post-Integration Era: Why MCP is Necessary

The process of connecting LLMs to external systems has been a significant bottleneck for innovation. Each new application, data source, or API required a bespoke, one-off integration. For example, a developer wanting an LLM to access a customer’s Salesforce data, query a local database, and send a notification via Slack would need to write three separate, brittle, and non-interoperable pieces of code. This approach created deep “information silos,” where the LLM’s potential was hamstrung by the immense engineering effort required to grant it context. This ad-hoc integration paradigm was fundamentally unscalable from a software development viewpoint, hindering the development of complex, multi-tool AI agents.

In response to this systemic problem, Anthropic introduced the Model Context Protocol in November 2024. MCP is an open-source, open-standard framework designed to be the universal interface for AI systems. The protocol was almost immediately adopted by other major industry players, including OpenAI, Google DeepMind, and Microsoft, signaling a collective recognition of the need for a unified standard.

The most effective way to understand MCP’s purpose is through the “USB cables for AI” analogy. Before USB, every device had a proprietary connector, requiring a different cable for charging, data transfer, and video output. USB replaced this chaos with a single, standardized port that could handle all these functions. Similarly, MCP replaces the chaos of bespoke AI integrations with a single, standardized protocol. It provides a universal way for an AI model to connect to any compliant data source or tool, whether it’s reading files from a local computer, searching a knowledge base, or executing actions in a project management tool.

The vision of MCP is to enable the creation of sophisticated, agentic workflows that can be maintained inexpensively as individual tool and service interfaces may occasioanlly change internally. By providing a common interface language for tools, MCP allows an AI to compose multiple capabilities in a coordinated fashion. For example, an agent could use one tool to look up a document, a second tool to query a CRM system for related customer data, and a third tool to draft and send a message via a messaging API. This ability to chain together actions across distributed resources is the foundation of advanced, context-aware AI reasoning and automation. The rapid, cross-industry adoption of MCP was not merely the embrace of a new feature, but a strategic acknowledgment that the entire AI ecosystem would benefit more from a shared protocol layer than from maintaining proprietary integration moats. The N-to-M integration problem connecting N applications to M tools was a drag on the entire industry. By solving it, MCP unlocked a new frontier of possibility, shifting developer focus from building brittle pipes to orchestrating intelligent workflows.

Architectural Deep Dive: Hosts, Clients, and Servers

The MCP architecture is built upon a clear separation of concerns, defined by three primary actors: Hosts, Clients, and Servers. Understanding the distinct role of each is critical to designing and implementing MCP-compliant systems:

- MCP Host: The Host is the primary LLM application that the end-user interacts with. It is responsible for managing the overall session, initiating connections, and, most importantly, responsibility for user security. The Host discovers the tools available from connected servers and presents them to the LLM. When the LLM decides to use a tool, the Host intercepts the request and presents it to the user for explicit approval. In the context of this discusion, LM Studio serves as the MCP Host. Other examples include the Claude Desktop application or IDEs with MCP plugins.

- MCP Server: A Server is a program that exposes external capabilities, data and tools to an MCP Host. This is the component that bridges the gap between the abstract world of the LLM and the concrete functionality of an external system. A server could be a lightweight script providing access to the local file system (the focus of our implementation), or it could be a robust enterprise service providing access to a platform like GitHub, Stripe, or Google Drive. Developers can use pre-built servers or create their own to connect proprietary systems to the MCP ecosystem.

- MCP Client: The Client is a connector component that resides within the Host. This is a subtle but important architectural detail. The Host application spawns a separate Client for each MCP Server it connects to. Each Client is responsible for maintaining a single, stateful, and isolated connection with its corresponding Server. It handles protocol negotiations, routes messages, and manages the security boundaries between different servers. This one-to-one relationship between a Client and a Server ensures that connections are modular and a failure in one server does not impact others.

The conceptual design of MCP draws significant inspiration from the Language Server Protocol (LSP), a standard pioneered by Microsoft for use in development tools like Visual Studio Code, Emacs, and other editors and IDEs. Before LSP, adding support for a new programming language to an IDE required writing a complex, IDE specific extension. LSP standardized the communication between IDEs (the client) and language-specific servers. A developer could now write a single “language server” for Python, and it would provide features like code completion, linting, and syntax highlighting to any LSP-compliant editor. In the same way, MCP standardizes the communication between AI applications (the Host) and context providers (the Server). A developer can write a single MCP server for their API, and it can provide tools and resources to any MCP-compliant application, be it Claude, LM Studio, or a custom-built agent.

The MCP Specification: Communication and Primitives

The MCP specification defines the rules of interoperability between Hosts and Servers, ensuring robust communication across the ecosystem. It is built on established web standards and defines a clear set of capabilities.

At its core, all communication within MCP is conducted using JSON-RPC 2.0 messages. This is a lightweight, stateless, and text-based remote procedure call protocol. Its simplicity and wide support across programming languages make it an ideal choice for a universal standard. The protocol defines three message types: Requests (which expect a response), Responses (which contain the result or an error), and Notifications (one-way messages that don’t require a response).

An MCP Server can offer three fundamental types of capabilities, known as primitives, to a Host:

- Tools: These are executable functions that allow an LLM to perform actions and produce side effects in the external world. A tool could be anything from write_file to send_email or create_calendar_event. Tools are the primary mechanism for building agentic systems that can act on the user’s behalf. This primitive is the main focus of the implementation in this chapter.

- Resources: These are read-only blocks of contextual data that can be provided to the LLM to inform its reasoning. A resource could be the content of a document, a record from a database, or the result of an API call. Unlike tools, resources do not have side effects; they are purely for information retrieval.

- Prompts: These are pre-defined, templated messages or workflows that a server can expose to the user. They act as shortcuts for common tasks, allowing a user to easily invoke a complex chain of actions through a simple command.

To manage compatibility as the protocol evolves, MCP uses a simple, date-based versioning scheme in the format YYYY-MM-DD. When a Host and Server first connect, they negotiate a common protocol version to use for the session. This ensures that both parties understand the same set of rules and capabilities, allowing for graceful degradation or connection termination if a compatible version cannot be found.

Security and Trust: The User-in-the-Loop Paradigm

The power of MCP in enabling an AI to access files and execute arbitrary code necessitates a security model that is both robust and transparent. The protocol’s design is founded on the principle of explicit user consent and control.

The MCP specification deliberately places the responsibility for enforcing security on the MCP Host application, not on the protocol itself. The protocol documentation uses formal language to state that Hosts must obtain explicit user consent before invoking any tool and should provide clear user interfaces for reviewing and authorizing all data access and operations. This is a pragmatic design choice. Rather than attempting to build a complex, universal sandboxing mechanism into the protocol, a task of immense difficulty, the specification keeps the protocol itself simple and pushes the responsibility for security to the application layer, which is better equipped to handle user interaction.

This places a significant burden on developers of Host applications like LM Studio. They are required to implement effective safety features, such as the tool call confirmation dialog, which intercepts every action the LLM wants to take and presents it to the user for approval. This “human-in-the-loop” approach makes the user the final arbiter of any action.

Furthermore, the protocol treats tool descriptions themselves as potentially untrusted. A malicious server could misrepresent what a tool does. Therefore, the user must understand the implications of a tool call before authorizing it. This security model is powerful because it is flexible, but its effectiveness is entirely dependent on the vigilance of the end-user and the clarity of the Host’s UI.

The following table compares MCP to previous tool-use paradigms, illustrating its advantages in standardization, discoverability, and composability.

Table 1: Comparison of Tool-Use Paradigms

| Paradigm | Standards | Discovery | Security | Developer Overhead | Composability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manual API Integration | None | Manual (API Docs) | Application-Specific | High (per integration) | Difficult |

| Proprietary Function Calling | Vendor-Specific | API-Based | Platform-Enforced | Medium (per platform) | Limited (within vendor ecosystem) |

| Model Context Protocol (MCP) | Open Standard | Protocol-Based (tools/list) | Host/User-Enforced | Low (per tool server) | High (cross-platform) |

The Local AI Ecosystem: LM Studio as an MCP Host

To move from the theory of MCP to a practical implementation, a suitable Host environment is required. LM Studio, a popular desktop application for running LLMs locally and the topic of this book, has emerged as a key player in the local AI ecosystem and now functions as a full-featured MCP Host. This section details the relevant capabilities of LM Studio and the specific mechanisms for configuring and using it with MCP servers.

Overview of LM Studio for Local LLM Inference

LM Studio is designed to make local LLM inference accessible to a broad audience. It is free for internal business use and runs on consumer-grade hardware across macOS, Windows, and Linux. By leveraging highly optimized inference backends like llama.cpp for cross-platform support and Apple’s MLX for Apple Silicon, LM Studio allows users to run a wide variety of open-source models from Hugging Face directly on their own machines, ensuring data privacy and offline operation.

For developers, LM Studio provides two critical functionalities that form the foundation of our local agentic system:

- OpenAI-Compatible API Server: LM Studio includes a built-in local server that mimics the OpenAI REST API. This server, typically running at http://localhost:1234/v1, accepts requests on standard OpenAI endpoints like /v1/chat/completions and /v1/embeddings. This is a powerful feature because it allows developers to use the vast ecosystem of existing OpenAI client libraries (for Python, TypeScript, etc.) with local models, often by simply changing the base_url parameter in their client configuration. Our testing client will use this API to interact with the LLM running in LM Studio.

- MCP Host Capabilities: Beginning with version 0.3.17, LM Studio officially supports acting as an MCP Host. This important update allows the application to connect to, manage, and utilize both local and remote MCP servers. This capability bridges the gap between raw local inference and true agentic functionality, enabling local models to interact with the outside world through the standardized MCP interface. The rapid implementation of this feature was likely driven by strong community demand for standardized tool-use capabilities in local environments.

This combination of a user-friendly interface, a powerful local inference engine, an OpenAI-compatible API, and full MCP Host support makes LM Studio an ideal platform for developing and experimenting with private, local-first AI agents. It democratizes access to technologies that were previously the exclusive domain of large, cloud-based providers, allowing any developer to build sophisticated agents on their own hardware.

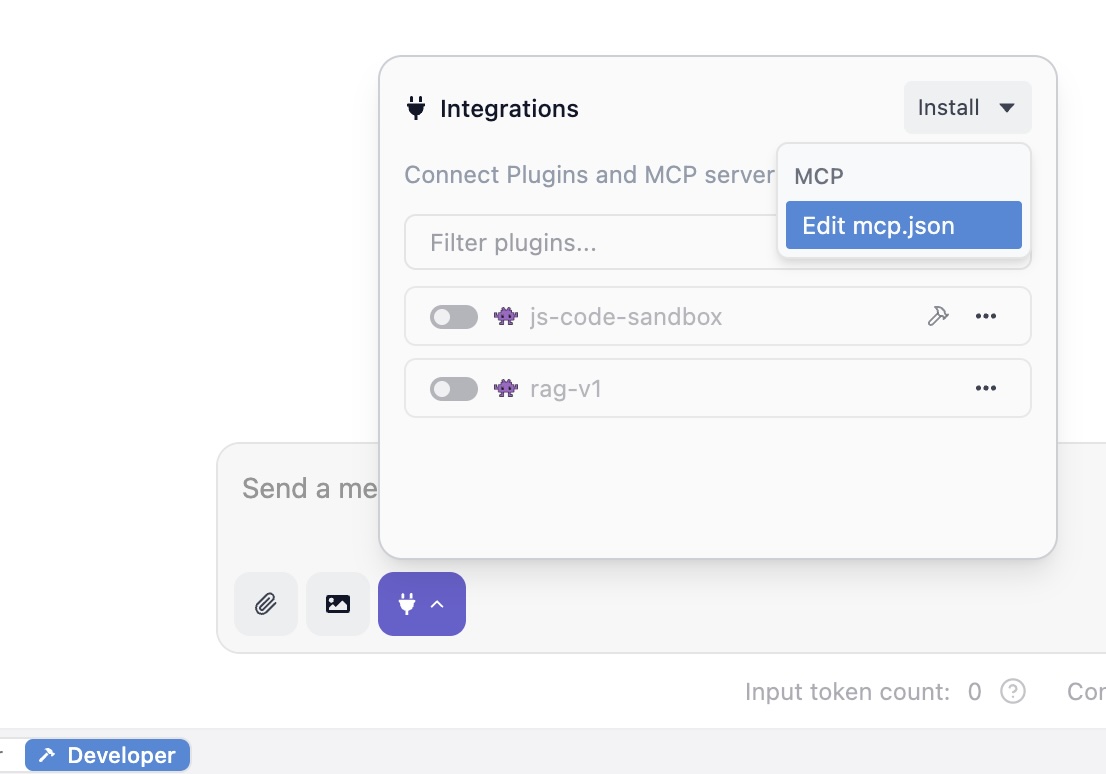

Enabling the Bridge: The mcp.json Manifest

The configuration of all MCP servers within LM Studio is centralized in a single JSON file named mcp.json. This file acts as a manifest, telling the LM Studio Host which servers to connect to and how to run them.

The file is located in the LM Studio application data directory:

1 macOS & Linux: ~/.lmstudio/mcp.json

2 Windows: %USERPROFILE%/.lmstudio/mcp.json

While it can be edited directly, the recommended method is to use the in-app editor, which can be seen in a later figure showing a screenshot of LM Studio. This approach avoids potential file permission issues and ensures the application reloads the configuration correctly.

The structure of mcp.json follows a notation originally established by the Cursor code editor, another MCP-enabled application. The root of the JSON object contains a single key, mcpServers, which holds an object where each key is a unique identifier for a server and the value is an object defining that server’s configuration.

LM Studio supports two types of server configurations:

- Local Servers: These are servers that LM Studio will launch and manage as local child processes. This is the method used later for running our example Python services. The configuration requires the command and args keys to specify the executable and its arguments. An optional env key can be used to set environment variables for the server process.

- Remote Servers: These are pre-existing servers running on a network, which LM Studio will connect to as a client. This configuration uses the url key to specify the server’s HTTP(S) endpoint. An optional headers key can be used to provide HTTP headers, which is commonly used for passing authorization tokens.

The reliance on a plain JSON file for configuration is characteristic of a rapidly evolving open-source tool. While a full graphical user interface for managing servers would be more user-friendly, a configuration file is significantly faster to implement and provides full power to technical users. This often results in a scenario where community-generated resources, such as blog posts and forum guides, become the de facto documentation for new features, supplementing the official guides. The following table consolidates this community knowledge into a clear reference:

Table: Table 2: LM Studio mcp.json Configuration Parameters

| Key | Type | Scope | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

command |

String | Local Server | The executable program used to start the server process. | "python" |

args |

Array of Strings | Local Server | A list of command-line arguments to pass to the executable. | ["server.py", "--port", "8000"] |

env |

Object | Local Server | Key-value pairs of environment variables to set for the server process. | {"API_KEY": "secret"} |

url |

String | Remote Server | The full HTTP or HTTPS endpoint of a running remote MCP server. | "https://huggingface.co/mcp" |

headers |

Object | Remote Server | Key-value pairs of HTTP headers to include in every request to the server. | {"Authorization": "Bearer <token>"} |

Practical Host-Side Security: Intercepting and Approving Tool Calls

In alignment with the MCP security philosophy, LM Studio implements a critical safety feature: the tool call confirmation dialog. This mechanism acts as the practical enforcement of the “user consent” principle.

When an LLM running within LM Studio determines that it needs to use an external tool, it generates a structured request. Before this request is sent to the corresponding MCP server, the LM Studio Host intercepts it and pauses the execution. It then presents a modal dialog to the user, clearly stating which tool the model wants to invoke and displaying the exact arguments it intends to use.

This dialog empowers the user with complete agency over the process. They can:

- Inspect: Carefully review the tool name and its parameters to ensure the action is intended and safe.

- Edit: Modify the arguments before execution if necessary.

- Approve: Allow the tool call to proceed for this one instance.

- Deny: Block the tool call entirely.

- Whitelist: Choose to “always allow” a specific, trusted tool. This adds the tool to a whitelist (managed in App Settings > Tools & Integrations), and LM Studio will no longer prompt for confirmation for that particular tool, streamlining workflows for trusted operations.

This user-in-the-loop system is the cornerstone of MCP’s security in a local environment. It acknowledges that local models can be made to call powerful, and potentially dangerous, tools. By making the user the final checkpoint, it mitigates the risk of unintended or malicious actions. Additionally, LM Studio enhances stability by running each configured MCP server in a separate, isolated process, ensuring that a crash or error in one tool server does not affect the main application or other connected servers.

Strategic Integration: A Blueprint for Local MCP-Powered Agents

With a solid understanding of MCP principles and the LM Studio Host environment, the next step is to formulate a clear strategy for building a functional agent. This section outlines a concrete project plan, defining the agent’s capabilities, the end-to-end workflow, model selection criteria, and an approach to error handling.

Defining the Goal: Implementing Three Example Agent Resources

The project goal is to design and build a Local File System Agent. This is an ideal first project as it is both useful and intuitive. In the next Python example we limit file system operations to fetching the names of files in a local directory but you are free to extend this example to match your specific use cases. It directly demonstrates the value of MCP for local AI by enabling an LLM to interact with the user’s own files, a common and highly useful task.

The agent will be equipped with three fundamental capabilities, which will be exposed as MCP tools:

- List Directory Contents: The ability to receive a directory path and return a list of the files and subdirectories within it.

- Perform exact arithmetic: This circumvents the problems LLMs sometimes have perfroming precise math operations.

- Get the local time of day: This show how to make system calls in Python.

These three tools provide solid examples for implementing external resources for a wide range of tasks, from summarizing documents to generating code and saving it locally.

The End-to-End Workflow: From Prompt to Action

The complete operational flow of our agent involves a multi-step dance between the user, the LLM, the MCP Host (LM Studio), and our custom MCP Server. The following sequence illustrates this process for a typical user request:

Step 1: User Prompt: The user initiates the workflow by typing a natural language command into the LM Studio chat interface. For example: “Read the file named project_brief.md located in my Downloads folder and give me a summary.”

Step 2: LLM Inference and Tool Selection: The local LLM, loaded in LM Studio, processes this prompt. Because it is a model trained for tool use, it recognizes the user’s intent to read a file. It consults the list of available tools provided in its context by the Host and determines that the read_file tool is the most appropriate. It then formulates a structured tool call, specifying the tool’s name and the argument it has extracted from the prompt (e.g., {‘path’: ‘~/Downloads/project_brief.md’}).

Step 3: Host Interception and User Confirmation: LM Studio, acting as the vigilant Host, intercepts this tool call before it is executed. It presents the user with the confirmation dialog, displaying a message like: “The model wants to run read_file with arguments: {‘path’: ‘~/Downloads/project_brief.md’}. Allow?”. Step 4: User Approval: The user verifies that the request is legitimate and safe so the model is asking to read the correct file and clicks the “Allow” button.

Step 5: Client-Server Communication: Upon approval, LM Studio’s internal MCP Client for our server sends a formal JSON-RPC request over its stdio connection to our running Python MCP Server process.

Step 6: Server-Side Execution: Our Python server receives the tools/call request. It parses the method name (read_file) and the parameters, and invokes the corresponding Python function. The function executes the file system operation, opening and reading the contents of ~/Downloads/project_brief.md.

Step 7: Response and Contextualization: The server packages the file’s content into a successful JSON-RPC response and sends it back to the LM Studio Host. The Host receives the response and injects the file content back into the LLM’s context for its next turn.

Step 8: Final LLM Response: The LLM now has the full text of the document in its context. It proceeds to perform the final part of the user’s request, summarization, and generates the final, helpful response in the chat window: “The project brief outlines a plan to develop a new mobile application…”

This entire loop, from prompt to action to final answer, happens seamlessly from the user’s perspective, but relies on the clear, standardized communication defined by MCP.

Model Selection Criteria for Effective Tool Use

A critical component of this strategy is selecting an appropriate LLM. Not all models are created equal when it comes to tool use. The ability to correctly interpret a user’s request, select the right tool from a list, and generate a syntactically correct, structured JSON call is a specialized skill that must be explicitly trained into a model.

Using a generic base model or an older chat model not fine-tuned for this capability will almost certainly fail. Such models lack the ability to follow the complex instructions required for tool use and will likely respond with plain text instead of a tool call.

For this project, it is essential to select a model known for its strong instruction-following and function-calling capabilities. Excellent candidates available through LM Studio include modern, open-source models such as:

- Qwen3 variants

- Gemma 3 variants

- Llama 3 variants

- Mixtral variants

These models have been specifically trained on datasets that include examples of tool use, making them proficient at recognizing when a tool is needed and how to call it correctly.

The success of any MCP-powered agent is fundamentally dependent on the quality of the “semantic contract” established between the LLM and the tools it can use. This contract is not written in code but in natural language and structured data: the tool’s name, its parameters, and, most importantly, its description. The LLM has no innate understanding of a Python function; it only sees the text-based manifest provided by the MCP server. Its ability to make an intelligent choice hinges on how clearly and accurately this manifest describes the tool’s purpose and usage. A vague description like:

1 def tool1(arg1):

is useless. A clear, descriptive one like:

1 def read_file_content(path: str) -> str:

2 "Reads the entire text content of a file at the given local path."

3 ...

provides a strong signal that the model can understand and act upon. In agentic development, therefore, writing high-quality docstrings and schemas transitions from being a documentation “best practice” to a core functional requirement for the system to work at all.

Error Handling and Recovery Strategy

A robust agent must be able to handle failure gracefully. The MCP specification provides a two-tiered error handling mechanism, and our strategy must leverage it correctly:

- Protocol-Level Errors: These errors relate to the MCP communication itself. Examples include the LLM trying to call a tool that doesn’t exist (tool_not_found) or providing arguments in the wrong format (invalid_parameters). These failures indicate a problem with the system’s mechanics. Our server should respond with a standard JSON-RPC error object. These errors are typically logged by the Host and are not intended for the LLM to reason about.

- Tool Execution Errors: These errors occur when the tool itself runs but fails for a logical reason. For example, the read_file tool might be called with a path to a file that does not exist, or the write_file tool might be denied permission by the operating system. These are not protocol failures; they are runtime failures. In these cases, the server should return a successful JSON-RPC response. However, the content of the response should be an error object that includes a descriptive message for the LLM (e.g., {“isError”: true, “message”: “File not found at the specified path.”}).

This distinction is crucial. By reporting execution errors back to the LLM as content, we empower it to be more intelligent. The LLM can see the error message, understand what went wrong, and decide on a next step. It might inform the user (“I couldn’t find that file. Could you please verify the path?”), or it might even try to recover by using a different tool (e.g., using list_directory to see the available files). This approach makes the agent more resilient and the user experience more interactive.

Architectural Design for a Python-Based MCP Server

This section provides a detailed architectural design for the custom MCP server. It outlines the project setup, code structure, and the key design patterns that leverage the official MCP Python SDK to create a robust and maintainable server with minimal boilerplate.

Setting up the Development Environment

A clean and consistent development environment is the first step toward a successful implementation. The recommended tool for managing Python packages for this project is uv, a high-performance package manager and resolver written in Rust. The official MCP Python SDK documentation recommends its use for its speed and modern approach to dependency management.

The environment setup process is as follows:

Install uv: If not already installed, uv can be installed with a single command:

- On macOS or Linux: curl -LsSf https://astral.sh/uv/install.sh | sh

- On Windows (PowerShell): powershell -ExecutionPolicy ByPass -c “irm https://astral.sh/uv/install.ps1 | iex”

Initialize the Project: Create a new directory for the project and initialize it with uv.

1 mkdir math-and-time-and-files

2 cd math-and-time-and-files

3 uv init

4 uv venv

5 source.venv/bin/activate # On macOS/Linux

6 #.venv\Scripts\activate # On Windows

7 uv add fastmcp "mcp[cli]" openai

This setup provides a self-contained environment with all the necessary tools, ready for development. The last statement installs most libraries that you would likely need.

Designing the Server: A Modular and Declarative Approach

The design of the server will prioritize clarity, simplicity, and adherence to modern Python best practices. For a project of this scope, a single Python file, server.py, is sufficient and keeps the entire implementation in one place for easy review.

The central component of our architecture is the fastmcp.FastMCP class from the Python fastmcp package. This high-level class is an abstraction layer that handles the vast majority of the protocol’s complexity automatically. It manages the underlying JSON-RPC message parsing, the connection lifecycle (initialization, shutdown), and the dynamic registration of tools. By using FastMCP, the design can focus on implementing the business logic of the tools rather than the intricacies of the protocol.

The primary design pattern for defining tools will be declarative programming using decorators. The SDK provides the @tool() decorator, which can be applied to a standard Python function to expose it as an MCP tool. This approach is exceptionally clean and “Pythonic.” It allows the tool’s implementation and its MCP definition to coexist in a single, readable block of code, as opposed to requiring separate registration logic or configuration files.

The design of the fastmcp Python SDK, and the FastMCP class in particular, is a prime example of excellent developer experience. The raw MCP specification would require a developer to manually construct complex JSON-RPC messages and write JSON Schemas to define their tools. This process is both tedious and highly prone to error. The SDK’s designers abstracted this friction away by creating the FastMCP wrapper and the @tool decorator. This design cleverly leverages existing Python language features, functions, docstrings, and type hints that developers already use as part of writing high-quality, maintainable code. The SDK performs the complex translation from this familiar Pythonic representation to the formal protocol-level representation automatically. This significantly lowers the cognitive overhead and barrier to entry, making MCP server development accessible to a much wider audience of Python developers.

Defining the Tool Contract: Signatures, Type Hints, and Docstrings

The FastMCP class works through introspection. When it encounters a function decorated with @mcp.tool(), it automatically inspects the function’s signature to generate the formal MCP tool manifest that will be sent to the Host. This automated process relies on three key elements of the Python function:

- Function Name: The name of the Python function (e.g., def list_directory(…)) is used directly as the unique name of the tool in the MCP manifest.

- Docstring: The function’s docstring (the string literal within “““…”””) is used as the description of the tool. As discussed previously, this is the most critical element for the LLM’s ability to understand what the tool does and when to use it.

- Type Hints: The Python type hints for the function’s parameters and return value (e.g., path: str -> list[str]) are used to automatically generate the inputSchema and output schema for the tool. This provides a structured contract that the LLM must adhere to when generating a tool call, ensuring that the server receives data in the expected format.

The example file LM_Studio_BOOK/src/mcp_examples/server.py contains the definitions of three tools. The following script, server.py, implements the MCP server with the three defined file system tools. The code is heavily commented to explain not only the “what” but also the “why” behind the implementation choices, particularly concerning error handling and security.

1 from fastmcp import FastMCP

2 import os

3

4 # Initialize the MCP server

5 app = FastMCP("my-mcp-server")

6

7 @app.tool()

8 def add_numbers(a: int, b: int) -> int:

9 """Adds two numbers together."""

10 return a + b

11

12 @app.tool()

13 def get_current_time_for_mark() -> str:

14 """Returns the current time."""

15 import datetime

16 return datetime.datetime.now().strftime("%H:%M:%S")

17

18 @app.tool()

19 def list_directory(path: str = ".") -> list[str]:

20 """

21 Lists all files and subdirectories within a given local directory path.

22 The path should be an absolute path or relative to the user's home directory.

23 """

24 try:

25 # Implementation logic will go here

26 expanded_path = os.path.expanduser(path)

27 return os.listdir(expanded_path)

28 except FileNotFoundError:

29 return # Return an empty list if path not found

30

31 # To run the server (e.g., via stdio for local development)

32 if __name__ == "__main__":

33 app.run()

Later we will see how to activate these three tools in LM Studio.

Data Flow and State Management

In general the tools will be designed to be stateless. Each tool call is an atomic, self-contained operation. The get_current_time_for_mark function, for example, simply calls a Python operating system function to get the local time. It does not rely on any previous state stored on the server. This is a robust design principle for MCP servers, as it makes them simple to reason about, test, and scale. The state of the conversation is managed by the LLM and the Host within the chat history, not by the tool server.

The data flow for a tool call is a straightforward JSON-RPC exchange. The Host sends a request object containing the method (“tools/call”) and params (the tool name and arguments). The server processes this request and sends back a response object containing either the result of the successful operation or an error object if a protocol-level failure occurred.

The following table provides a quick reference to the key SDK components used in this design.

| Component Type | Purpose | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

FastMCP Class |

High-level server implementation that simplifies tool registration and lifecycle management. | app = FastMCP() |

@app.tool() Decorator |

Registers a Python function as an MCP tool, automatically generating its manifest from its signature and docstring. | @app.tool() def my_function():... |

app.run() Method |

Starts the MCP server, listening for connections via the standard input/output (stdio) transport. | if __name__ == "__main__": app.run() |

str, int, list, dict, bool, None

|

Used with type hints to define the inputSchema for tool arguments. All types must be JSON-serializable. |

def get_user(id: int) -> dict: |

The following table provides a quick reference to the key SDK components used in this design.

| Component Type | Purpose | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

FastMCP Class |

High-level server implementation that simplifies tool registration and lifecycle management. | app = FastMCP() |

@app.tool() Decorator |

Registers a Python function as an MCP tool, automatically generating its manifest from its signature and docstring. | @app.tool() def my_function():... |

app.run() Method |

Starts the MCP server, listening for connections via the standard input/output (stdio) transport. | if __name__ == "__main__": app.run() |

str, int, list, dict, bool, None

|

Used with type hints to define the inputSchema for tool arguments. All types must be JSON-serializable. |

def get_user(id: int) -> dict: |

LM Studio Integration and Execution Guide

Follow these steps to run the complete system:

- Start LM Studio: Launch the LM Studio application. In the “Search” tab (magnifying glass icon), download a tool-capable model like lmstudio-community/Meta-Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct-GGUF. Once downloaded, go to the “Chat” tab (speech bubble icon) and select the model from the dropdown at the top to load it into memory.

- Start the API Server: Navigate to the “Local Server” tab (two arrows icon) in LM Studio and click the “Start Server” button. This will activate the OpenAI-compatible API at http://localhost:1234/v1.

- Configure mcp.json:

Paste the following JSON configuration into the editor. Replace /Users/markw/GITHUB/LM_Studio_BOOK/src/mcp_examples/ with the absolute path to the math-and-time-and-files directory you created.

1 {

2 "math-and-time-and-files": {

3 "command": "/Users/markw/GITHUB/LM_Studio_BOOK/src/mcp_examples/.venv/bin/python",

4 "args": [

5 "/Users/markw/GITHUB/LM_Studio_BOOK/src/mcp_examples/server.py"

6 ]

7 }

8 }

Note that we will be running the tools in the file server.py that we saw earlier.

Save the file (Ctrl+S or Cmd+S). LM Studio will automatically detect the change and launch your server.py script in a background process. You should see the log messages from your server appear in the “Program” tab’s log viewer.

Run the New Tools

Open a new chat tab in LM Studio. Enter a prompt like what time is it?

Please remember that using the “electrical plug” icon seen in the last figure, you must enable tools to use in each new chat session. By default tools are configured to require human approval for their use - often turn this setting to auto after the Python code for a tool is complete.

You will by default see a popup dialog asking you to approve the tool tall. Review the request (“The model wants to run get_current_time_for_mark …”) and click “Allow”.

Observe the result: after you approve the tool call the model running in LM Studio uses the results of the tool call to print a human-readable (not JSON) result.

Advanced Considerations and Future Trajectories

Having successfully implemented tools, it is valuable to consider the broader context and future potential of this technology. MCP is more than just a protocol for single-tool use; it is an architectural primitive for building complex, multi-faceted AI systems.

Composing Multiple MCP Servers for Complex Workflows

The true power of the Model Context Protocol is realized through composability. An MCP Host like LM Studio is not limited to a single server; it can connect to and manage multiple MCP servers simultaneously. This enables the creation of agents that can orchestrate actions across disparate systems and data sources.

Consider a more advanced workflow that combines, for example, a hypothetical custom LocalFileSystemServer with a pre-built, community-provided MCP server for GitHub. An agent could execute the following sequence:

- Read a local bug report: The agent uses the read_file tool from the LocalFileSystemServer to ingest the details of a bug from a local text file.

- Search for related issues: The agent then uses a search_issues tool provided by the GitHub MCP server, using keywords from the bug report to find similar, existing issues in a specific repository.

- Analyze and summarize: The agent processes the search results and the original bug report.

- Write a summary file: Finally, the agent uses the write_file tool from this hypothetical server to save a new file containing a summary of its findings and a list of potentially related GitHub issues.

This entire workflow is orchestrated by the LLM, which seamlessly switches between tools provided by two different, independent servers. This level of interoperability, made simple by the standardized protocol, is what enables the development of truly powerful and versatile AI assistants.

The Emerging MCP Ecosystem: Registries and Pre-built Servers

The standardization provided by MCP is fostering a vibrant ecosystem of tools and integrations. A growing number of pre-built MCP servers are available for popular enterprise and developer tools, including Google Drive, Slack, GitHub, Postgres, and Stripe. This allows developers to quickly add powerful capabilities to their agents without having to write the integration code themselves.

To facilitate the discovery and management of these servers, the community is developing MCP Registries. A registry acts as a centralized or distributed repository, like to a package manager where developers can publish, find, and share MCP servers. The official MCP organization on GitHub hosts a community-driven registry service, and Microsoft has announced plans to contribute a registry for discovering servers within its ecosystem.

This trend points toward the creation of a true “app store” or “plugin marketplace” for AI tools. A developer building an agent will be able to browse a registry, select the tools they need (e.g., a calendar tool, a weather tool, a stock trading tool), and easily add them to their Host application. This will dramatically accelerate the development of feature-rich agents and create a new “Tool Economy,” where companies and individual developers can create and even monetize specialized MCP servers for niche applications.

The Trajectory of Local-First AI Agents

The convergence of powerful open-source LLMs, accessible local inference engines like LM Studio, and a standardized tool protocol like MCP marks an inflection point for AI. It signals the rise of the local-first AI agent that is a new class of applications that are private, personalized, and deeply integrated into a user’s personal computing environment.

The future of this technology extends beyond simple chat interfaces. We can anticipate the emergence of “ambient assistants” embedded directly into operating systems, IDEs, and other desktop applications. These assistants will use MCP as the common language to securely access and reason about a user’s personal context like their local files, emails, calendar appointments, and contacts without sending sensitive data to the cloud. They will be able to perform complex, multi-step tasks on the user’s behalf, seamlessly blending the reasoning power of LLMs with the practical utility of desktop and web applications. MCP provides the critical, standardized plumbing that makes this future possible.

The importance of using local inference tools like LM Studio and Ollama is enabling developers to develop “privacy first” systems that either leak no personal or proprietary data, or less private data, to third party providers.

Concluding Analysis and Recommendations

Here we have detailed the architecture, strategy, and implementation of tools written in Python and addressed the possibility of building a local AI agent using the Model Context Protocol. The key conclusions are:

- MCP successfully standardizes tool use, solving a fundamental integration problem and creating a foundation for a new, interoperable ecosystem of AI capabilities. Its design, inspired by the Language Server Protocol, effectively decouples tool providers from AI application providers.

- LM Studio democratizes agentic AI development. By acting as a robust MCP Host, it empowers any developer to build and experiment with sophisticated, tool-using agents on their own hardware, using private data and open-source models.

- The MCP and fastMCP Python SDKs both offer an exemplary developer experience. The FastMCP class and its declarative, decorator-based approach abstract away the protocol’s complexity, allowing developers to create powerful custom tools with minimal boilerplate and in a familiar, “Pythonic” style.

For developers embarking on building with MCP, the following recommendations are advised:

- Start with Read-Only Tools: Begin by implementing tools that only read data (like

list_directoryandread_file). This allows for safe experimentation with the protocol and workflow without the risk of unintended side effects. - Prioritize Descriptive Tool Manifests: The most critical element for a tool’s success is its description. Write clear, unambiguous docstrings that accurately describe what the tool does, its parameters, and what it returns. This “semantic contract” is what the LLM relies on to make intelligent decisions.

- Exercise Extreme Caution with Write-Enabled Tools: Tools that modify the file system or have other side effects are incredibly powerful but also dangerous. The security of the system relies on the user’s vigilance. Always assume a tool could be called with malicious intent and rely on the Host’s confirmation dialog as the final, essential safeguard.

The Model Context Protocol is more than just a technical specification; it is a key piece of infrastructure for the next generation of computing. By providing a secure and standardized bridge between the reasoning capabilities of Large Language Models and the vast world of external data and tools, MCP is paving the way for a future of more helpful, capable, and personalized AI assistants.

MCP Wrap Up

Dear reader, while we have looked at the architecture and rationale behind MCP, we have barely skimmed the surface of possible applications. I am a computer scientist with a preference for manually designing and writing code. My personal approach to using MCP with tools to build agentic systems is to put most of the complexity in the Python tool implementations and to rely less on LLMs except to primarily act as a human friendly interface between user interactions and backend systems and data stores. In fairness, I have a “minority opinion” compared to most people working in our industry.

I enjoy writing my own MCP servers and perhaps dear reader you do also. That said, a web search for “open source MCP server examples” shows a rich and developing ecosystem of open source projects that can easily be used with LM Studio and other MCP-compliant platforms. Some open source projects you might enjoy or find useful are:

- Brave Search API https://github.com/brave/brave-search-mcp-server

- Fetch content of web pages https://github.com/modelcontextprotocol/servers/tree/main/src/fetch

- Access local file systems https://github.com/modelcontextprotocol/servers/tree/main/src/filesystem

Here are a few maintained lists of MCP servers:

- GitHub user wong2’s list: https://github.com/wong2/awesome-mcp-servers

- MCP servers from Docker: https://github.com/docker/mcp-servers