Explore capabilities, not features

As software features are implemented, and user stories become ready for exploratory testing, it’s only logical to base exploratory testing sessions on new stories or changed features. Although it might sound counter-intuitive, story-oriented exploratory testing sessions lead to tunnel vision and prevent teams from getting the most out of their effort.

Stories and features are a solid starting point for coming up with good deterministic checks. However, they aren’t so good for exploratory testing. When exploratory testing is focused on a feature, or a set of changes delivered by a user story, people end up evaluating whether the feature works, and rarely stray off the path. In a sense, teams end up proving what they expect to see. However, exploratory testing is most powerful when it deals with the unexpected and the unknown. For this, we need to allow tangential observations and insights, and design new tests around unexpected discoveries. To achieve this, exploratory testing can’t be focused purely on features.

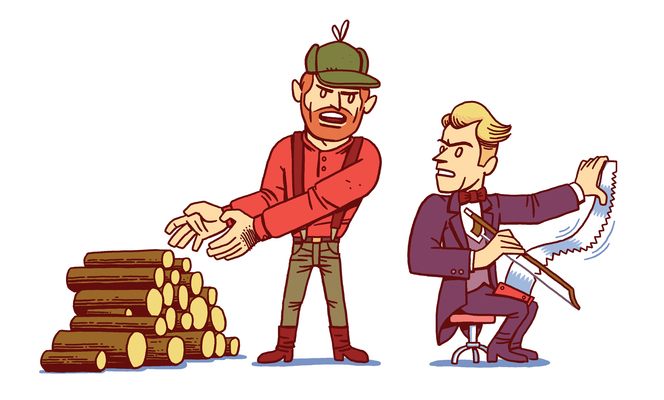

Good exploratory testing deals with unexpected risks, and for this we need to look beyond the current piece of work. On the other hand, we can’t cast the net too widely, because testing would lack focus. A good perspective for investigations that balances wider scope with focus is around user capabilities. Features provide capabilities to users to do something useful, or take away user capabilities to do something dangerous or damaging. A good way to look for unexpected risks is not to explore features, but related capabilities instead.

Key benefits

Focusing exploratory testing on capabilities instead of features leads to deeper insights and prevents tunnel vision.

A good example is the contact form we built for MindMup. The related software feature was that a support request is sent when a user fills in the form. We could have explored the feature using multiple vectors, such as field content length, email formats, international character sets in the name or the message, but ultimately this would only focus on proving that the form worked. Casting the net a bit wider, we identified two capabilities related to the contact form:

- A user should be able to contact us for support easily in case of trouble. We should be able to support them easily, and solve their problems.

- Nobody should be able to block or break the contact channels for other users through intentional or unintentional misuse.

We set those capabilities as the focus of our exploratory testing session, and this led us to look at the accessibility of the contact form in case of trouble, and the ease of reporting typical problem scenarios. We discovered two critically important insights.

The first was that a major cause of trouble would not be covered by the initial solution. Flaky and unreliable network access was responsible for many incoming support requests. But when the Internet connection for users went down randomly, even though the form was filled in correctly, the browser might fail to connect to our servers. If someone suddenly went completely offline, the contact form wouldn’t actually help at all. None of those situations should happen in an ideal world, but when they did, that’s when users actually needed support. So the feature was implemented correctly, but there was still a big capability risk. This led us to offer an alternative contact channel for when the network was not accessible. We displayed the alternative contact email address prominently on the form, and also repeated it in the error message if the form submission failed.

The second big insight was that people might be able to contact us, but without knowing the internals of the application, they wouldn’t be able to provide information for troubleshooting in case of data corruption or software bugs. That would pretty much leave us in the dark, and disrupt our ability to provide support. As a result, we decided not to even ask for common troubleshooting information, but instead obtain and send it automatically in the background. We also pulled out the last 1000 events that happened in the user interface, and sent them automatically with the support request, so that we could replay and investigate what exactly happened.

How to make it work

To get to good capabilities for exploring, brainstorm what a feature allows users to do, or what it prevents them from doing. When exploring user stories, try to focus on the user value part (‘In order to…’) rather than the feature description (‘I want …’).

If you use impact maps for planning work, the third level of the map (actor impacts) are a good starting point for discussing capabilities. Impacts are typically changes to capabilities. If you use user story maps, the top-level item in the user story map spine related to the current user story is a nice starting point for discussion.