Describe what, not how

By far the most common mistake inexperienced teams make when describing acceptance criteria for a story is to mix the mechanics of test execution with the purpose of the test. They try to describe what they want to test and how something will be tested all at once, and get lost very quickly.

Here is a typical example of a description of how something is to be tested:

Scenario: basic scenario

Given the user Mike logs on

And the user clicks on "Deposit"

And the page reloads

Then the page is "Deposit"

And the user clicks on "10 USD"

And the page reloads

Then the page is "Card Payment"

When the user enters a valid card number

And the user clicks on "Submit"

And the payment is approved

And the page reloads

Then the page is "Account"

And the account field shows 10 USD

And the user clicks on "Find tickets"

And the user clicks on "Quick trip"

And the page reloads

Then the page is "Tickets"

And the price is 7 USD

And the user clicks on "Buy tickets"

Then the purchase is approved

And the page reloads

And a ticket confirmation number is displayed

And the account field shows 3 USD

This is a good test only in the sense that someone with half a brain can follow the steps mechanically and check whether the end result is 3 USD. It is not a particularly useful test, because it hides the purpose in all the clicks and reloads, and leaves the team with only one choice for validating the story. Even if only a tiny fraction of the code contains most of the risk for this scenario, it’s impossible to narrow down the execution. Every time we need to run the test, it will have to involve the entire end-to-end application stack. Such tests unnecessarily slow down validation, make automation more expensive, make tests more difficult to maintain in the future, and generally just create a headache for everyone involved.

An even worse problem is that specifying acceptance criteria like this pretty much defeats the point of user stories – to have a useful conversation. This level of detail is too low to keep people interested in discussing the underlying assumptions.

Avoid describing the mechanics of test execution or implementation details with user stories. Don’t describe how you will be testing something, keep the discussion focused on what you want to test instead. For example:

Scenario: pre-paid account purchases

Given a user with 10 USD in a pre-paid account

When the user attempts to buy a 7 USD ticket

Then the purchase is approved

And the user is left with 3 USD in the account

When most of the clutter is gone, it’s easier to discuss more examples. For example, what if there is not enough money in the account?

| Pre-paid balance | Ticket cost | Purchase status | Resulting balance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 USD | 7 USD | approved | 3 USD |

| 5 USD | 7 USD | rejected | 5 USD |

This is where the really interesting part comes in. Once we remove the noise, it’s easy to spot interesting boundaries and discuss them. For example, what if the pre-paid balance is 6.99 and someone wants to buy a 7 USD ticket?

As an experiment, go and talk to someone in sales about that case – most likely they’ll tell you that you should take the customer’s money. Talk to a developer, and most likely they’ll tell you that the purchase should be rejected. Such discussions are impossible to have when the difficult decisions are hidden behind clicks and page loads.

Key benefits

It’s much faster to discuss what needs to be done instead of how it will be tested in detail, so keeping the discussion on a higher level allows the team to go through more stories faster, or in more depth. This is particularly important for teams that have limited access to business sponsors, and need to use their time effectively.

Separately describing the purpose and the mechanics of a test makes it easier to use tests for communication and documentation. The next time a team needs to discuss purchase approval rules with business stakeholders, such tests will be a great help. Although the mechanics of testing will probably be irrelevant, a clear description of what the current system does will be an excellent start for the discussion. In particular it will help to remind the team of all the difficult business decisions that were made months ago while working on previous stories. An acceptance criterion that mixes clicks and page loads with business decisions is useless for this.

Decoupling how something will be tested from what is being tested significantly reduces future test maintenance costs. When a link on a web page becomes a button, or users are required to log in before selecting products, we only have to update the mechanics of testing. If the purpose and the mechanics are mixed together, it is impossible to identify what needs to change. That’s the reason why so many teams suffer from record-and-replay test maintenance.

How to make it work

A good rule of thumb is to split the discussions on how and what into two separate meetings. Business sponsors are most likely not interested in the mechanics of testing, but they need to make decisions such as the $6.99 purchase. Engage decision-makers in whiteboard discussions on what needs to be tested, and postpone the discussion on how to test it for the delivery team later.

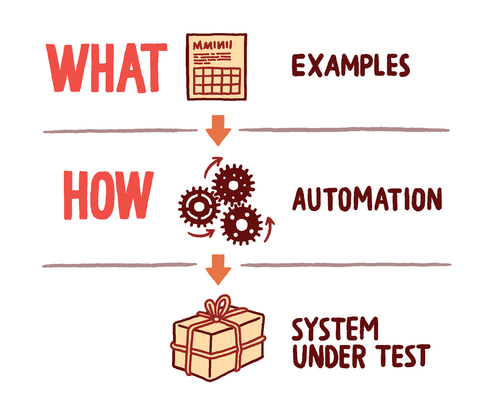

If you use a tool to capture specifications with examples, such as Cucumber, FitNesse or Concordion, keep the human-readable level focused on what needs to be tested, and keep the automation level focused on how you’re checking the examples. If you use a different tool, then clearly divide the purpose of the test and the mechanics of execution into different layers.