7. Talking to the system

So far we’ve looked at software that communicates with your users, via text based or graphical interfaces, and system software that doesn’t need to talk to users at all. One thing that both types of software have in common is the need to deal with the underlying system that it sits on top of. That system is a structure containing the file system, operating system, hardware interfaces and various system level services.

When programming for the web you typically don’t interact with hardware, lower level aspects of the system and so on. Indeed in many cases you specifically take steps to prohibit your users from doing so! In contrast, dealing with printers, sound-cards and other hardware is a common requirement when constructing many types of software, and interfacing with system level services is often a necessity. You will work with portions of the file system from web pages, but with off-line software you usually have the freedom and resources to work with a wider range of file formats, larger file sizes and more privileged files.

In this chapter we’ll look at some of the different ways to interact with these resources both from within PHP and with the aid of helper applications, and some of the issues to consider when doing so.

7.1 Filesystem interactions

There are many different types of data files that software needs to commonly interact with, from images to text files, formatted documents to videos, structured data to configuration files, and many more. PHP has built in functions for reading, writing, parsing and displaying many different types of data files, and between Pear, Pecl, Composer and third party libraries even more types are covered. On many systems, particularly Unix variants, helper applications can also be called to further extend the range of file types covered. In fact, there are very few file types that you will struggle to deal with in PHP, and those tend to be proprietary formats with closely guarded specifications. If you stick to open formats, and in particular standards-based formats, you will invariably find the tools you need in the PHP eco-system.

7.2 Data files & formats

Appendix B contains a reference list of functions/libraries/helpers available for a wide range of common formats. Remember that where a particular version of a format doesn’t appear, it is often usable using the functions for the generic format it is based on (e.g. many XML based formats are perfectly amenable to being manipulated by the XML tools listed).

Always bear in mind that data files are a large vector for security exploits, and even where software is operated locally by trusted users, those users may inadvertently try to open files from malicious sources. Always treat external data as potentially tainted, and treat un-vetted extensions/helpers as if they have potential security vulnerabilities.

7.3 Dealing with large files

When you don’t have a limit on the time your script can run, you will find that you can work with bigger files than you may be used to when using PHP on the web. In general, you can deal with them in the same way as you would with smaller files. However one big problem you may run into is memory usage. It’s important to understand how PHP uses memory when loading and processing files so that you can make appropriate choices in your code. Many of the libraries for handling particular file formats listed in Appendix B will deal with opening and processing large files efficiently on your behalf, so this section is most relevant when you do your own file processing, or use a library that requires you to pass it raw data (rather than a filename).

First lets look at simple methods for reading in a file in one go. PHP has two easy to use functions for doing this, file() and file_get_contents(). The former reads the file into an array, the latter into a single string.

1 <?

2

3 $filename = 'bigfile.csv';

4

5 echo("Size of file : ".filesize($filename)." bytes\n");

6

7 $memory1 = memory_get_usage();

8

9 $file_array = file($filename);

10

11 $memory2 = memory_get_usage();

12

13 $file_string = file_get_contents($filename);

14

15 $memory3 = memory_get_usage();

16

17 echo("Memory used by array : ".($memory2-$memory1)." bytes\n");

18

19 echo("Memory used by string : ".($memory3-$memory2)." bytes\n");

Running this on a sample large file I had lying around, gave the following output

1 Size of file : 186097433 bytes

2 Memory used by array : 296969824 bytes

3 Memory used by string : 186097588 bytes

So we can see that reading the file (about 177Mb) into a string adds an overhead of 155 bytes, which is not too bad at all. However reading this file into an array adds an additional 105Mb to the original size of the file! In PHP, arrays are a very versatile data structure, they “can be treated as an array, list (vector), hash table (an implementation of a map), dictionary, collection, stack, queue, and probably more” (according to the PHP manual). However this versatility comes at a price, and that is the additional memory used for storing the structure information. So before loading the file, consider whether the processing you are going to do on the data can be done on a string, or whether the extra overhead of an array is worth it for the manipulation capabilities. If you need a traditional array or hash like structure without the versatility of the PHP array type, look into the PHP SPL (Standard PHP Library) which contains a range of “traditional” data structures that may be more optimised for your use case.

|

Further Reading SPL book in the PHP Manual |

Sometimes, no matter what type of data structure you read your file into, there isn’t enough memory available on the system, you hit a memory limit imposed for your script, or you just need to keep memory usage low in general. Often processing of a datafile can be done on a line-by-line (or chunk-by-chunk) basis, and PHP allows us to read in a file piece by piece rather that in one go. Assuming you discard the data you’ve read before you read some more (unset it, overwrite it or write it out to a file, for example), then you will just use enough memory to store that one line or chunk.

1 <?

2

3 $filename = 'bigfile.csv';

4

5 $memory1 = memory_get_usage();

6

7 $file_string = file_get_contents($filename);

8

9 $memory2 = memory_get_usage();

10

11 unset($file_string);

12

13 $memoryBase = memory_get_usage();

14

15 $file_handle = fopen($filename, 'r');

16

17 while ($line = fgets($file_handle)) {

18

19 $memoryCurrent = memory_get_usage();

20

21 if ($memoryCurrent > $memoryBase) { $memoryHigh = $memoryCurrent;};

22

23 };

24

25 echo("Memory used by single string : ".($memory2-$memory1)." bytes\n");

26 echo("Max memory used when reading by line : ".

27 ($memoryHigh-$memoryBase)." bytes\n");

On my sample file this gave the output :

1 Memory used by single string : 186097768 bytes

2 Max memory used when reading by line : 9000 bytes

which should illustrate the extreme differences in memory usage using the two different techniques.

If you’re working with files that are, or may be, greater than 2Gb in size you should also be aware that some filesystem functions may not return the correct (or any) result for files bigger than that on many platforms. This is because these platforms use a 32-bit integer, PHP’s integer type is signed, and 2Gb is the largest size that can be represented by a signed 32-bit integer. This affects functions like filesize(), stat() and fseek(). You can of course access external commands to replace some of these functions, for instance wc -c on Linux will return the number of bytes in a file for all files supported by the operating system. On 64 bit Linux, with a recent version of glibc installed, you can compile PHP with the D_LARGEFILE_SOURCE -D_FILE_OFFSET_BITS=64 flag for better large file support, though be aware if you are writing scripts for distribution that this obviously won’t be an available option for all.

In all of these examples, remember that your script has to work within any memory limit you or PHP has imposed. By default the PHP CLI SAPI turns off the memory limit, you can type php -r "echo(ini_get('memory_limit'));" at the command line to see the default memory limit (-1 means no limit). From within your script, ini_get('memory_limit') will tell you the current maximum, and memory_get_usage() will tell you what you’re currently using.

Handling memory usage when dealing with large amounts of data is something that often trips programmers up. As we’ve seen, understanding how the various functions we use operate can help us process that data more efficiently and help us to minimise the memory we use.

7.4 Understanding filesystem interactions

PHP has a number of filesystem related extensions, many of which are part of the PHP core or compiled into most PHP distributions and contain hundreds of useful functions. Most of them operate in a simple straight-forward manner, allowing you to get and set file and directory information and manipulate files and the filesystem as you would expect. We won’t cover most of them here, as I’m sure many will be familiar to you from your web projects and they are covered well in the PHP manual.

|

Further Reading Filesystem related functions in the PHP manual |

Many of these functions ape command line programs that you may be used to, like chmod, mkdir, touch and so on, and operate broadly how you expect. However there is a difference that raises its head in longer running script, and revolves around PHP caching filesystem information to increase performance, which we will look at next.

7.5 The PHP file status and realpath caches

On the web, speed is king. PHP operates two information caches to speed up access to the filesystem. The first is the file status cache, which caches information about a given file (like whether it exists, whether it is readable, it’s size and type, and so on). The second is the realpath cache, which caches the actual, real path for a given file or directory (expanding out symlinks, relative paths, ‘.’ and ‘..’ paths, include_path’s and so on). Information is added to the cache automatically by PHP each time it encounters a new file, and is then used by any number of functions the next time they attempt to look at that same file. With a web page that’s gone in the blink of an eye where little may have happened on the filesystem, this is often a good trade-off for increased performance.

However the chances that the details of a file or path may change while your script runs obviously increase with the length of time that your script takes to execute. Therefore PHP gives us a couple of options for working with these two caches.

The following example shows the file status cache in action, and how to use clearstatcache() to clear it.

7.6 Working with cross platform & remote filesystems

7.7 Accessing the Windows Registry

The Windows Registry is a structured hierarchical database which Windows and other applications use to store configuration information. While not used universally by all applications, most will store some information in the Registry, and the operating system itself uses it extensively. We can access the registry from PHP too, allowing us to check and set configuration information both for our own applications, and if we have the right permissions, other applications and the OS itself. To do this, we need to use the win32std extension with PHP.

7.8 Linux signals

On Unix and Linux systems, “signals” are a method that the Operating System (possibly at the behest of a user) can use to send, well, signals to a process. The OS interrupts the normal execution flow of the process to deliver the signal, allowing the process to act on the signal immediately (if it wishes to do so). There are a wide range of signals that can be passed, including requests to terminate, error condition signalling and polling notifications. Common signals have been codified in the POSIX standards and a full list can be found on Wikipedia, and the list supported by PHP can be found in the PHP manual :

|

Further Reading POSIX signals on Wikipedia PHP supported signals in the PHP manual “Signaling PHP” by Cal Evans, a whole book just about signals! |

We can listen and respond to these signals from our PHP scripts using the PCNTL extension. The following script demonstrates how to do this. It uses a PHP feature called “ticks”, which allow a callback function be executed after every N statements. We don’t need to do anything with ticks, we simply need to enable it (using a declare construct) so that it is available to the PCNTL functions to use as they deem fit.

7.8.1 Sending Signals

7.9 Linux timed-event signals

Sometimes we want our scripts to do something every-so-often, for example checking the status of a resource, do some clean-up, update a log file or similar. There are a couple of ways to achieve this. The simplest is by using the sleep() or usleep() functions to sit and wait for a number of seconds/microseconds before performing a task. This is not always of use, as when you call sleep() the script simply stops and waits for that amount of time rather than continuing to do other useful work. In the previous section we briefly looked at PHP “ticks”, which allows us to run a callback function every N (potentially useful) statements. This allows us to do useful work in-between calls to the callback function, however there is no guarantee on how long those statements will take to execute so we can’t wait for a specific length of time. In fact, PHP has no internal way of keeping track of time in this way. However using POSIX signals, which we looked at in the previous section, we can ask the system to set an “alarm” for us a certain number of seconds into the future. When the “alarm” goes off, the system will interrupt PHP with a signal, which we can handle to run our callback function.

7.10 Printing (to paper)

7.11 Audio

7.12 Databases - no change here

7.13 Other hardware and system interactions

7.14 Raspberry Pi : PHP and the RP

The purpose of the following sections (aside from being an excuse for the author to buy a new toy) are to explore the low-power, credit-card-sized-PC phenomenon that is the Raspberry Pi (RP). We’ll look at how to get started using PHP on the RP, how to build some basic electronic switch circuits for the GPIO (General Purpose Input Output) connector, and how to access GPIO connected electronics from within PHP. These sections are only an introduction to the subject, covering the points essential to using PHP on the RP, so we will also point you in the direction of other comprehensive (and usually programming language agnostic) information covering everything the RP can do. You will be building PHP controlled robot overlords in no time!

At its heart, the RP is simply another Linux computer with a low power ARM-based CPU. There are an assortment of operating systems freely available for the RP, mostly based on either Debian, Fedora or Arch Linux. There is also a version of Risc OS (the ARM-native OS) available, however we’ll assume that you are using one of the Linux based distro’s. Any commands given have only been tested on Raspbian (the official OS of the RP) which is a Debian derivative, but should work in a similar manner (or functionality should be similarly available) on the other Linux based OSes.

7.15 Raspberry Pi : The basics of tri-state logic

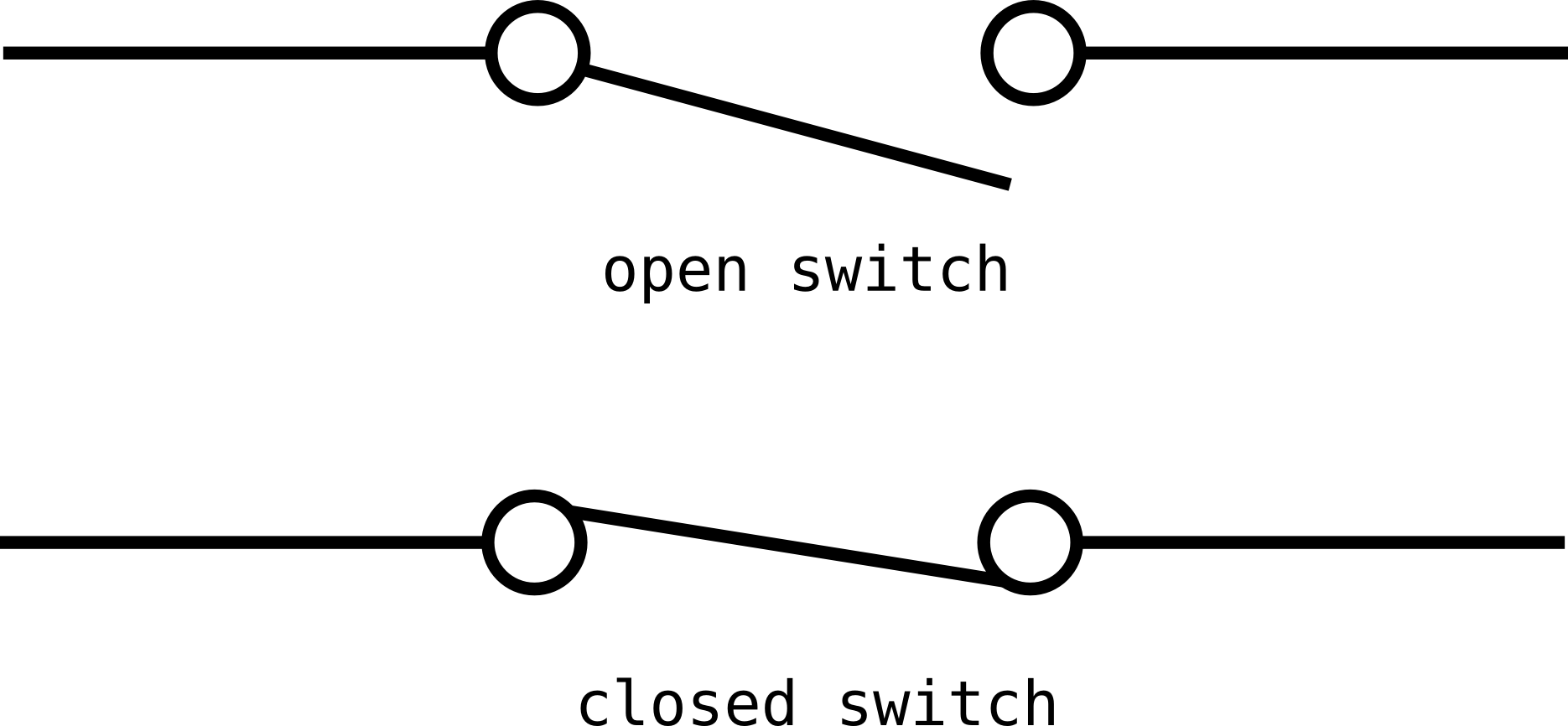

As programmers we’re all very familiar with binary logic. True or false, yes or no, 1 or 0, on or off. These binary states form the basis of all programming, and even in high level languages like PHP they are a staple of keeping program state. Likewise, one of the staples of electronic input is the switch. Whether it’s a light switch, a key on a keyboard, a magnetic reed switch, a PIR motion sensor or many other input types, it often boils down to (one or more) logical switches which we can measure to see if they are in one state (open, unpressed, no motion) or the other (closed, pressed, motion detected). The symbols in wiring diagrams for basic switches usually look like the following :

Example switch symbols

Very binary. The temptation as a programmer with little electronics experience, when presented with a RP and a switch, is to connect one of the GPIO pins to Gnd (ground) via the switch, and poll it to see its state. If you do this, you’ll probably notice the state change when you switch the switch back and forth. Great. But keep watching. You’ll probably start to see the input changing state all on its own, somewhat randomly. What you’re actually seeing is third flapping or “floating” state. Without a direct connection to a positive voltage or ground, the state of the GPIO pin will float or flap about and can’t be relied upon to be correct. It’s a bit like a PHP variable with register_globals turned on : if you haven’t explicitly set it yourself, you can’t trust its value.

7.16 Raspberry Pi : Accessing the GPIO ports from PHP

Let’s say we’ve built ourself a basic switch circuit like the one described above. Perhaps the switch is a door bell push button, connected to, say, GPIO pin 17, and we want to ring out the chimes via a connected speaker when someone pushes the button. We need to whip up a PHP script that can poll the GPIO pin for it’s state, and detect when the button is pushed. This is really a “hello world” type script, the very basics of what you can do, but it should serve to introduce you to GPIO programming.

Before we look at the PHP code necessary to do this, it is helpful to understand how things work “under the hood”. The Linux kernel contains a special interface module for dealing with GPIO pins (not just on the RP, but also on other PCs and embedded boards that have them), and as the interface is implemented using the Unix model of “everything is a file”, you can actually access them with standard shell commands by hand, if necessary.

7.17 Raspberry Pi : Using the rest of the hardware

Much of the RP hardware is standard PC type hardware, accessing the sound jack, USB ports or HMDI output is pretty much as you would expect. Beyond those, and the standard GPIO pins discussed above, there are a couple more specialised pieces of hardware on the RP that you can play with, including I2C and SPI interfaces which we’ll look at below.

7.18 Raspberry Pi : Further resources

There are many, many more RP tutorials, articles, books and kits available. I’ve listed some of the more popular online RP resources below, and while many of them don’t use PHP for the software portion of projects, you should be able to use the PHP libraries above to create most of the software you need. Education is one of the drivers behind the RP project, so many tutorials use higher-level languages aimed at programming beginners. This should make it easier to understand them and thus help when “translating” into PHP.