5. System software

In the previous chapter we looked at user facing software, that is, software which the human user interacts with directly. In this chapter we are going to look at what I will term “system software”, software that does things (generally) without a human driving it.

To write system software we typically need to create a “daemon”, which is a continuously running process. Once we’ve created the Daemon, we need to decide its primary function. Some daemons work continuously (measuring, monitoring, communicating and so on), others wait and work in response to events (network connections, system changes, user actions). We will look at how to create a daemon in PHP and set it working continuously. We will then look at how we can take that basic daemon and instead of working continuously, make it just spring into life to react to certain events that occur in our system.

In the user facing software we looked at in the previous chapter, the software is typically used by one person or process at a time. System software, on the other hand, often serves many different “clients” at the same time. A “client” in this context may be a network client (e.g. a web browser for a web server), a user process (a GUI client accessing your API server), a file (a log file for a logging server) or similar. While doing so it needs to remain “responsive”, that is one client shouldn’t have to wait while another client’s request finishes. Think how backed up the web would get if Apache could only serve one web page at at time! To manage concurrent tasks in PHP and maintain a responsive daemon, we can use task dispatch and management systems, which we will look at in the final part of this chapter.

5.1 Daemons in PHP

A daemon is a program that runs, usually continuously, as a background process. It often doesn’t interact with users directly, but performs background tasks or responds to system events or calls from other software, network requests or other machine-to-machine events. Examples of programs that run as daemons include Cron (which waits in the background and executes tasks based on the current time), and Apache (which sits and waits for calls from remote machines for web resources). Daemons usually :

- run permanently (or for a long time, or until a predetermined event),

- start up at boot time

- perform useful tasks

- are owned by root or a (non-human) system user.

However these criteria don’t universally apply to all daemons, in fact the only concrete thing daemons have in common is that they don’t have a controlling terminal (tty), and thus are deemed to be running “in the background”. Without a tty the software cannot get user input from the keyboard or display output back to the user 0via the terminal (though there are other ways to directly and indirectly interact with a user). Although consuming minimal resources was traditionally a key trait of background processes, that is not now commonly the case. Software “servers” such as Database Management Systems and Web Servers run as background daemons but often consume large (or even all) of the system resources and often have machines dedicated just to running them. So it may be best to think of daemons as any permanently running software which doesn’t usually directly interact with the user.

5.2 Creating a daemon

To create a daemon in PHP we use the PHP process control extension, or PCNTL, which is only available on Unix/Linux type systems. On Windows you can use the win32service pecl extension to control Windows “services” (aka daemons), including turning your own PHP script into a service. This extension is only in beta and documentation is sparse, so we won’t cover it here.

Most pre-compiled versions of PHP include the PCNTL extension, but if not you will need to re-compile PHP using the --enable-pcntl option, or install the extension using your package manager. See Appendix A for details.

The outline process for creating a daemon is as follows :

- We run a process (PHP script). We will call this the parent process.

- From the parent, we fork (copy) a child process.

- The parent process then exits. The child process is now parent-less.

-

initadopts the parent-less child process.initis the original process started by the kernel when it boots and is the ancestor of all processes. - We then dissociate (detach the child) from the terminal we started the parent in. This is so that

- any of our output doesn’t appear in the terminal

- killing the terminal won’t kill our child process

- we are truly running in the background

- To dissociate (detach), we need to :

- move the child process into it’s own POSIX process session

- fork it once again (into the grandchild process) and kill the child process

- close any file descriptors such as STDIN that may tie it to the terminal

Once all this is done, you will be returned to the command prompt in the terminal (assuming thats where you started your original parent process from) and your (grandchild) daemon will be running on its own. You will only be able to interact indirectly with your daemon from now on. Finally, assuming that the daemon is to run continuously (or for a set period of time) rather than just completing a task and exiting, the process will need to enter a loop where it will continuously cycle and, for instance, await events or perform continuous tasks. Its probably also wise to give it the ability to exit upon demand.

This may sound quite a long and involved process, however it is fairly straight forward in PHP. The following script follows this process and outlines the basics.

5.3 Network daemons using libevent

In the previous section we used a fairly basic while(1) { } event loop to keep our daemon running and responding to events or doing useful work. The advantage of that approach is that is very simple for basic needs and is implemented natively in PHP with no external dependencies. The downside however is that it leaves you to implement all of the details, and the complexity increases as your project grows.

One popular alternative to consider is libevent, a library which provides a framework for dealing with event based programming. This library can be accessed in PHP though two different PECL modules :

- pecl-libevent : This is an older module, and is fairly simple and straight forward to use. However it doesn’t support libevent2 (only 1.x versions, 1.4.0 or above.), and thus has fewer features

- pecl-event : This is a complete rewrite of previous Pecl module of the same name abandoned in 2004. It is currently actively developed, and supports libevent2. This has more options including specific classes tailored for HTTP, DNS, SSL and other types of event connections. For these reasons this is the module we will use in the examples below.

Libevent describes itself as “… a library that provides a mechanism to execute a callback function when a specific event occurs on a file descriptor or after a time-out has been reached”. In layman’s terms, this means that libevent will execute a function of your choice either at pre-determined time intervals, or when a particular “file descriptor” event occurs. “File descriptors” in PHP cover not just events occurring on actual files, but anything that can be treated as a file or stream. This includes network sockets and system streams like STDIN. In fact, due to a problem with epoll (a Linux kernel event notification system, used by libevent) compatibility, libevent typically cannot be used for file events (detecting file accesses and modifications etc.) on many platforms. Because of this, we will additionally look at inotify in the next section for use with file events. Indeed, you should only really consider libevent for network/stream type events, which is where it really shines.

Libevent also offers event buffering, so in demanding environments it will queue events for you to process at your leisure, and you won’t risk missing something because your script was off doing something else. This is particularly important in a non-multitasking environment like PHP. Note that libevent just deals with responding to events, not creating a daemon in the first place, so you will still need to use code from the previous section to turn your script into a daemon before using Libevent to do the work.

The following example shows how we can use the pecl-event module to call libevent to act as a very simple http server. For brevity the following example runs as a standard CLI process, you can daemonise it using the techniques discussed in the previous section if you need to.

5.4 File monitoring daemons using inotify

5.4.1 Using the inotify PECL extension

5.4.2 Using the inotifywait command

5.4.3 Inotify limits

5.5 Task dispatch & management systems

Earlier in this chapter we looked at how you can fork new processes, and we’ll look in the next chapter at how to execute or call, and talk to, other external commands. These examples should give you some good ideas of how you can create worker tasks to carry out processing in parallel with your main PHP scripts. There are many cases where rolling your own task/worker dispatch and management scripts is a good idea, but there are also many times when it may be more prudent to use something already written by an expert. Luckily in these cases we can take advantage of any one of a number of excellent task dispatch and management systems that work with PHP. A few of the more common and useful systems are listed below, but first we’ll look at one particular system - Gearman - which has fantastic PHP bindings and good community support, and is an ideal task system to break your teeth in with.

5.6 Gearman and PHP

From the PHP manual :

- “Gearman is a generic application framework for farming out work to multiple machines or processes. It allows applications to complete tasks in parallel, to load balance processing, and to call functions between languages. The framework can be used in a variety of applications, from high-availability web sites to the transport of database replication events.” http://www.php.net/manual/en/intro.gearman.php

In essence, Gearman is a “middle-man” between your main scripts and your worker scripts. Your main scripts can fire off tasks to Gearman, and Gearman will allocated those tasks to workers when they become available. It will then monitor the workers and report their progress back to the main script along with the results of the task. You can have multiple Gearman servers for redundancy, and you can operate everything in a distributed manner across many different machines. You simply tell your main scripts where your Gearman server(s) are, and start firing off tasks. You don’t even have to wait for the results of the tasks if you don’t want to, and you can register call-back functions to handle results from multiple tasks as they come in. To configure the worker scripts, you tell them where the Gearman server(s) are and specify which tasks that particular script can handle, and add a little code to feed back progress during the task if you wish. You then fire up your worker scripts and they sit and wait for tasks to come in.

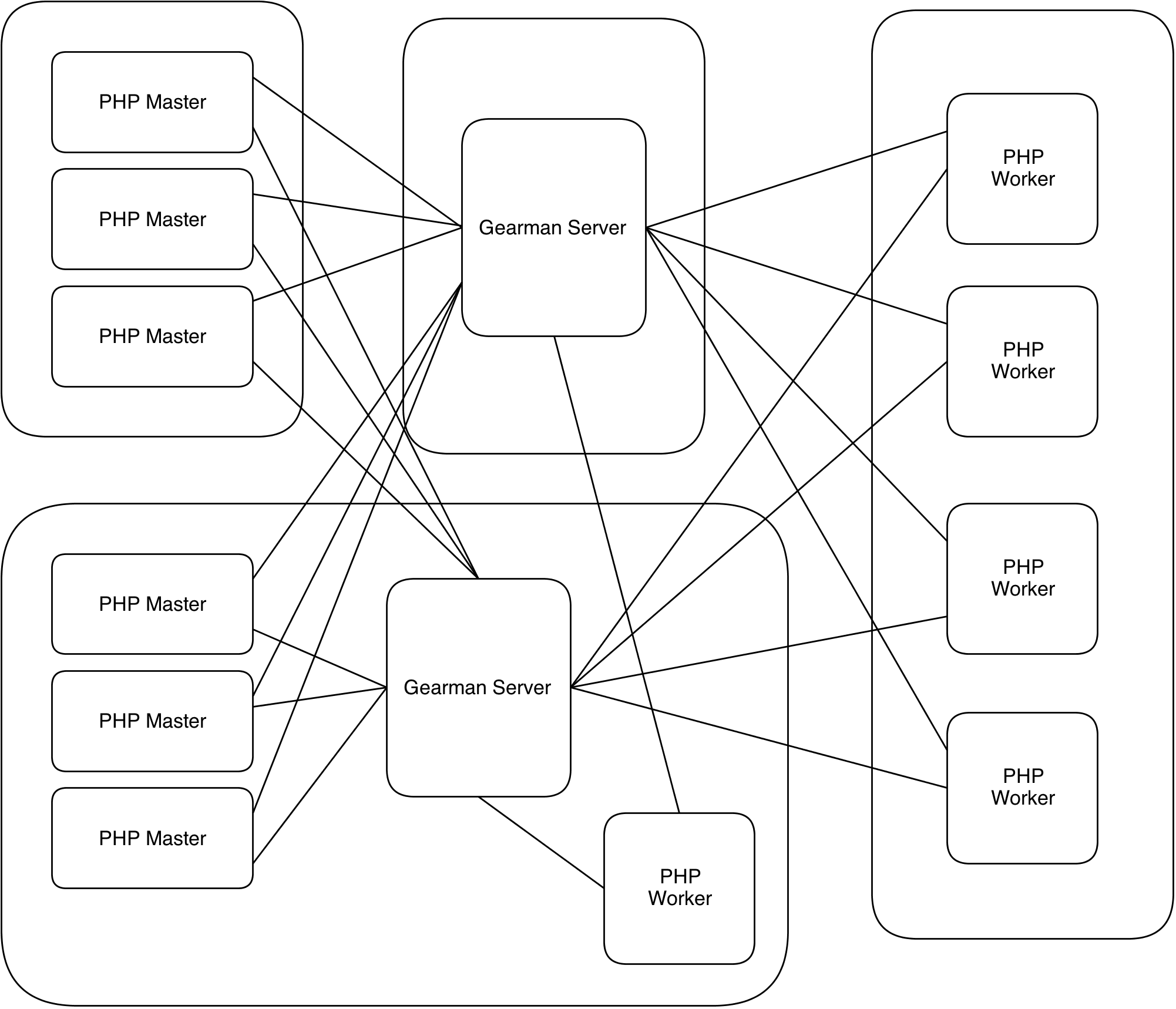

To help you visualise the possibilities available with Gearman, the diagram below shows a multi-machine setup with redundant Gearman servers.

Example with multiple machines/masters/clients/servers

In this particular network, we have six PHP “master” scripts running on two different machines. Each of these masters are connected to two Gearman server instances, one running on its own machine and one on a shared machine. In turn, there are five PHP “worker” scripts, four running on their own machine and one on the shared machine. All of the worker scripts are also connected to both of the two Gearman server instances. In this set up, you can see that if one of the Gearman server instances are unavailable, the system would continue to run as all components are connected to both server instances at the same time, and so can use either. Likewise if one or more master or worker scripts are unavailable, work still happens as the Gearman server instances dish out the jobs to the remaining scripts. And the best thing of all is that Gearman takes care of this “fallback” system for you. You simply point your masters and workers at the Gearman servers and Gearman deals with routing the jobs appropriately.