4 Thinking about thinking

The importance of not thinking

Now that you have some practice behind you, a little theorising would probably not be amiss here, and might even make some degree of sense.

So it worked.

Not spectacularly; but you did get some credible results.

You’ve proved that, to yourself, in practice.

But what worked?

Exactly. Whatever it was that worked, it worked best when you couldn’t see how it was going to work. It worked best when you let it. And if you tried to force it to work, it didn’t. The harder you look at it, the less there is to look at: it simply disappears into nothing. Yet if you pretend to turn away, and forget that it’s there, so to speak, it comes out quite happily on its own and does what is asked of it. Shy little beast, the pendulum.

It’s like looking at a dim star on a clear night. You can see it quite easily out of the corner of your eye: but look straight at it, and it vanishes. The centre of the eye’s field of vision can see colour, which the outer field can’t, but it isn’t so sensitive to dim light. And the harder you look, the less you can see. Since our central vision is so acute, logically it must, it seems, be better for looking at anything: but it doesn’t work that way. Instead, we have to flounder around at night trying to look at something by not looking at it, in order to get a better view of it. Strange.

The same’s true of working with a pendulum: we can get it to work best by not looking at how it works. We can think most clearly about it by looking at how not to think about it. A maze of paradoxes: thinking by not thinking. Contortions of the mind – no wonder dowsing seems insane at times!

A chaos of causes

The worst mistake is trying to find out how the pendulum really works, where the answers really come from, what really makes the pendulum move. That’ll drive you crazy. Don’t bother, just get on with it.

All right: so you insist. You want an answer: none of my usual evasions. There must be a single cause, a simple causal explanation, surely? After all, everything else does, doesn’t it? Well, doesn’t it?

Well, not exactly.

To be honest: no. It doesn’t.

In fact that’s the problem, that’s the mistake I keep going on about.

We’re taught in school that everything has a simple explanation, that everything can be shown to be caused by something else in a known way: and as long as you do leave it at school-level platitudes which explain everything so neatly, you can indeed ignore it at that. Everything fits, everything is certain, everything works within the ‘laws of nature’. As long as you don’t look too closely, that is: because it turns out that there are always exceptions to every rule. And those exceptions, we’re told, make up a further set of rules, the ones we’re taught as ‘fact’ at college rather than school. Except that there are exceptions to those rules; and so on and so on, ad infinitum. Those so-certain absolute rules turn out to be vague explanations that describe how things seem to work most of the time, probably, perhaps, as long as you don’t mind a few inconsistencies here and there, you can just ignore those. They don’t matter. Honest.

And that’s what we’re told is ‘scientific truth’ (even if it doesn’t bear much resemblance to real science as practised). Just sweep the inconsistencies under the carpet and they’ll disappear. Honestly. A pity about all those lumps in the carpet, though…

You still want to try to understand it all scientifically? Because it has to make sense that way, otherwise it can’t possibly work? All right, so let’s try to be scientific, to break it down into a simple chain of events caused by other events, other causes.

First, we know that the pendulum moves because your hand moves. All perfectly normal, strictly according to the laws of physics: nothing paranormal about that.

Your hand moves because a reflex muscular response is triggered. All perfectly normal, according to the laws of physiology – or rather, as far as we understand what we sometimes hope are laws of physiology.

And the reflex response is triggered by… um… er… well, let’s just forget that, shall we?

No?

Well, you did ask for it:

It’s caused by heat. Atmospheric changes. Ultrasonic scanning. Minute variations in magnetic fields. Radio waves. Geological and cosmic radiation. Interpretation of small clues in the landscape. An ultra-sensitive sense of smell. Special radiations that obviously must be physical even though no-one’s managed to isolate them yet. Resonance between the length of the pendulum thread and the natural vibrations of the object you’re looking for. Telepathy from the cat, which somehow knew anyway. Accessing the Akashic record. Astral projection. A message from your deceased great-grandmother. A small demon reaching out and moving your hand. It seemed like a good idea to move my hand then, honest. And – the all-time favourite – ‘it’s only coincidence’.

A chaos of causes – or non-causes. Pick your own: there’s plenty more in the bunch.

Explanations: they’re all explanations. Any one of them would do: in my time I’ve seen ‘proofs’ that demonstrate that all of them are true, in their own terms at least. Any explanation you care to cook up. But in a sense none of them are true, since most of them are mutually exclusive and very few of them make practical sense.

And you thought there would be just one, nice, neat, simple explanation?

On their own, none of these explanations are much use, either. Each explains just one thing, and then limits the possibilities to look further: to stop you getting it done another way. The most common of these explanations, of course, is that anyway it can’t work because it isn’t scientific, it doesn’t fit with the laws of chance, the laws of nature. Round the same loop we go… again and again. The only way out of the loop is to see that the explanation doesn’t matter: the use of the explanation does.

Take an explanation which says that getting the pendulum to work is well-nigh impossible, and suddenly it’s well-nigh impossible to get the pendulum to work. Invent an explanation that makes it easy, and suddenly it’s easy (or easier, at any rate). Why make things difficult? Don’t try to make it make sense in theory: it won’t. Get it to make sense in practice: that’s what matters. And you can use whatever explanation you like – however banal, however crazy – to make it work in practice: what matters is whether the explanation makes things easier, whether it makes sense in use.

That’s why I keep going on about the pendulum being part of a technology, ‘a practical art’, rather than a science. Technology is not ‘applied science’: it may use some scientific ideas from time to time, but it doesn’t have to be stuck with the rigid limitations of science at all.

In science, we have to pretend we know everything, understand everything; and everything has to fit within one interrelated structure of causes and effects, a closed net of logic with no loose ends. If something doesn’t fit, we’re in real trouble. That’s why so many scientists get so upset about intimations of the paranormal: if something can’t be forced to fit within the structure, it could actually destroy the whole beautiful edifice that’s been built up over so many centuries. So the solution that many scientists go for when faced with oddities like dowsing is to say that because it doesn’t fit, it can’t exist. In reality, that’s not science at all: that’s a parody of science, even if it is a very common one…

But in technology, we don’t have that problem: we don’t have to make things fit. They only have to work – whether they fit someone’s supposed rules or not. We quite happily admit the absence of omniscience, admit we don’t actually know how things work, and just get on with it instead. We don’t have a clue how even a simple thing like a light-bulb works in the way it does: if you take the explanations all the way down, you’ll find that every one of them is based on unknowns – for example, we don’t have a clue what magnetism or electricity really are at all. But we can use them. And we do use them. Using explanations that make it easier to use them, rather than ones that make it harder.

So let’s do the same with the pendulum. We know the basics of how to make it easier: holding the pendulum so that it can move freely, or so that it doesn’t argue with the wind. And we also know that thinking about causes, or trying to control the pendulum’s movements rather than letting it work ‘by itself’, don’t actually help either: we don’t know why it doesn’t help, but we do know that it doesn’t help, and that’s enough for now. Get on and use it. Don’t worry about it. It’s quite happy to work if you let it, as you’ll find out in time and in practice.

Getting through the maze

Learning any new skill is a confusing maze. At first it works wonderfully: then it doesn’t. At all. Beginner’s luck lapses into neophyte’s gloom, as you try harder and harder to get back at the ease with which you started as a beginner. Trying harder can be very trying: the bitter joke of “Try hard to relax”.

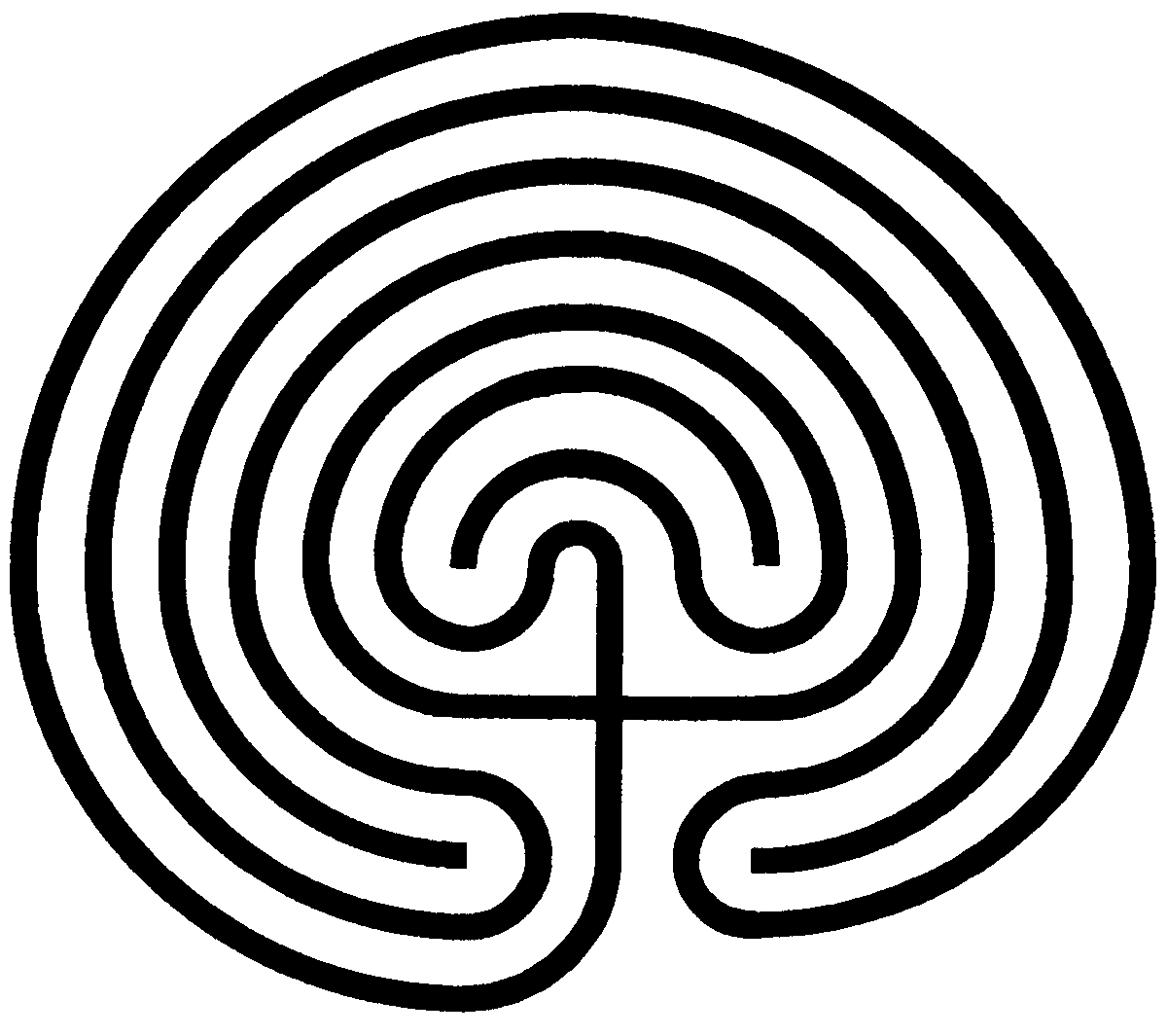

I find it useful to play with that analogy of the learning process as a maze – or rather a labyrinth, the old single-path maze design that occurs in so many cultures. Single-path because you know you’ll get there in the end if you don’t give up!

As you enter the labyrinth you move almost immediately to be very near the centre: beginner’s luck, we call it. You know what the target is, but you don’t know any ‘right’ way of doing it: and since you want to get there, you get there your own way, the way that suits you best.

Well, nearly there, at any rate. Not quite all the way there. Right, you say, how can I improve on this: and thinking hard, and asking around of various authorities who happen to be passing by (the opposite way, as you’ll notice later), you try harder. Missing the centre. Skirting round it, in fact.

Eventually you come round to another corner. This isn’t working well, you’re getting no closer to the centre, in fact you’re further away than you were at the best part of beginner’s luck. Try another way.

And back round the circle: further out than before. Eventually you notice: that way wasn’t right either, better try the way I started with. So back round the circle you go — further out than ever.

When you come back close to where you started again, realisation hits: you’re further out than when you started! I’m useless! I’ll never learn how to do it! I may as well give up now… It’s what I call ‘the dark night of the soul’.

But if you can make it round that curve, instead of jumping out of the maze in despair, almost immediately you’re close to the centre again: a boost to your morale. Second wind, we call it.

But again things get worse. After skirting the centre again (from the opposite direction to your original path as a beginner), you find yourself working outward. The path twists and turns, until you probably feel you’re going round the bend.

And then, without warning, you’re there. At the centre, the place you’ve been trying to reach for so long. Mastery of the skill. You know: you have the knowledge of how to use it, of how to use you with it, through it. It’s been a longer journey than it looked at first, perhaps. The only catch is: you now have to re-tread your steps to explain to others how you got there; and confuse them in the process, since you’re always looking outward from knowledge while they’re looking inward without it. Confusing; frustrating at times.

The Labyrinth

Every skill is like that. With most skills it’s not so obvious – there’s so much mechanical detail to learn for each, so many differing physical manipulations to master, that the sameness gets concealed. But learning to use a pendulum is exactly the same in that respect as learning cookery or carpentry: it’s just that there’s so little to it that you can hardly see the learned nature of it all at times. But you can learn it; have already learned a lot of it, although you may not realise it as yet.

Coincidence and imaginary

One ever-popular explanation used by people watching a pendulum going through its motions is “It’s all coincidence”. A generalised catch-all statement, that: anything you don’t understand, anything which doesn’t fit ‘the rules’, you can dismiss as ‘a mere coincidence’. If you can’t show the one true cause, in the best school-scientific manner – which, as we’ve seen, we can’t – then it can’t possibly be anything other than coincidence.

The problem is: that’s exactly what it is. The pendulum’s responses are just that: coincidence. Worse, they’re coincidences relating to things that are mostly imaginary. As I said before, one of the shortest and most accurate descriptions of dowsing is to say that it’s entirely coincidence and mostly imaginary.

Which puts an end to everything we’ve done so far. If it’s only coincidence, it must be meaningless.

That’s it: it’s only coincidence.

Except: we were actually getting some useful results back there. Your results may not have been brilliant, but you were able to sort those cards fairly well (at least, if you didn’t try too hard); you were able to use the pendulum to find the right cup of tea; you could tell which way up a battery was.

To call something ‘a mere coincidence’ isn’t actually an explanation at all: it’s a dismissal, a non-explanation that’s running away from explaining something because it knows perfectly well that it doesn’t have an explanation. And explanations, as we’ve seen, are only useful if they can show us a better way to use the pendulum: if not, they’re useless. Worse than useless, in fact, because they’re a hindrance that can stop us from being able to do anything at all.

The pendulum works; or rather you work and it tells you that you’re working by apparently working by itself. All coincidence, really. The pendulum’s fine, and so is your use of it: it’s the common understanding about what coincidence is – and isn’t – that’s wrong. And things imaginary, for that matter.

So we need a better look at this thing that’s ‘entirely coincidence and mostly imaginary’.

“It’s all coincidence’’

I have known people get rather upset at my description of the responses of the pendulum as ‘only coincidence’. It sounds too dismissive: but, as you’ll have realised by now, that isn’t what I mean at all. Equally I don’t like assigning too much meaning to coincidences: I’ve seen far too often the results of people taking every trivial event as immediate proof of the paranormal or else having some huge global significance. We can do without that problem here, thank you!

My difficulty here is that I don’t like inventing new words for the sake of it, and I can’t find a better word than ‘coincidence’. Sure, I could use Jung’s term ‘synchronicity’: but I’d only be mangling that one too. Although a lot of people do use it in a sense of ‘it wasn’t coincidence, it was a synchronicity’, in other words some kind of meaningful coincidence, Jung did originally design the word to have a specific meaning in relation to time: taken back to its component root-words, it literally means ‘the same time’. But the problem is that when we start to use a pendulum to investigate events within time – finding where something has been, or what the water-flow in a stream was like last year – the one thing we haven’t got is ‘the same time’. In fact what we have there is a coincidence of two times – the present and the past – in one place! So it’s much easier to stick with the word ‘coincidence’, and use it in its literal sense of ‘co-incidence’ (with the hyphen emphasised) rather than the mangled meaningless sense that most people seem to use so carelessly.

So let’s get one thing clear. To try to dismiss something by saying that it’s ‘only a coincidence’ doesn’t explain anything: in fact it’s an evasion, a non-explanation that doesn’t tell us anything at all. A ‘co-incidence’ is when two things happen to co-incide, happen to meet in some sense: what we would call an ‘event’, in conventional scientific terms. And that’s all it is: an event in which two things happen to co-incide, in space, in time or whatever. It doesn’t mean anything by itself; but it doesn’t mean nothing, either. A coincidence doesn’t have a meaning: coincidence and meaning are entirely separate.

The coincidence, or event, has no meaning – it’s just an event. What it means depends not on the event, but on the context of that event, what else is happening at the same place, the same time or whatever. In other words we assign meaning to coincidences according to what we see as significant, according to what we see as patterns of events. We see what we think is a regular pattern to a set of coincidences, and from that say that the later part of the pattern, the later set of events, is caused by the earlier stages of the pattern. That’s an explanation: it fits the facts. But those facts are themselves all coincidences, events. And it’s a moot point as to whether the pattern of events is really there, or whether we imagined the pattern to be there because it fits the explanation, and then say that the explanation fits the pattern because it fits the explanation because it fits the pattern… We determine what is ‘real’ and what is ‘mere coincidence’; we choose what to consider as ‘signal’ events and what to ignore as unimportant ‘noise’.

We’d go insane if we didn’t separate them, if we didn’t filter out the signal from the background noise. We call it discrimination, judgement, but perhaps a better word might be ‘sanity’. But it’s our choice as to which is which. Our choice as to what is sane and normal, and what is not. In other words, we have another paradox, first described by Stan Gooch: “Things have not only to be seen to be believed, but also have to be believed to be seen”.

This goes a great deal beyond playing games with a pendulum, so perhaps I’d better come back to the point: which is, how does this affect our use of the pendulum?

The answer is: a lot. Totally, in fact.

Because the pendulum’s responses are entirely coincidental.

What meaning we can glean from those responses comes from what we see as happening at that same time, at that same place.

But we choose to see what we expect to see, and have real difficulty in seeing what we don’t expect to see.

We ask a question: and expect an answer. The pendulum’s response coincides with the question: Yes or No. We hope.

It gains its meaning from the coincidence of the question with the response.

The catch is: the total question. The total context in which the response occurred: not just the question you hope you had framed so clearly in your mind. Absolutely everything. And I mean everything: in principle, the fact that you had marmalade for breakfast last Tuesday and that it’s raining in Guatemala at the moment could have a bearing on the pendulum’s response.

In most technology we cheat, and say that only information within a certain set of limits will matter. We call those limitations ‘the laws of nature’. And television pundits and others whose sanity and whose pay-cheques depend on you believing what they believe would certainly tell you that these laws of nature define the entirety of the universe. Which proves, they’ll insist, that anything that doesn’t fit these laws is ‘supernatural’ and therefore (by a rather neat piece of circular reasoning) doesn’t exist.

In fact these ‘laws’ are nothing of the kind. The reality is that we don’t know everything; indeed it’s quite easy to prove that we never will know everything (other than in a fleeting, intuitive sense, perhaps). And if we don’t know everything, we don’t actually know anything absolutely. In practical experience and in the real world of trying to get things to work the way we want them to, the result is, as any engineer will tell you, that there’s just one absolute law of the universe. It’s usually called ‘Murphy’s Law’. And it’s very simple: “if something can go wrong, it probably will – and usually in the worst possible way”.

The trouble is: there’s always something that can go wrong. Because there’s always something we hadn’t allowed for; there’s always something we didn’t know.

All the ‘laws of nature’ that we’re taught at school and college and beyond are, in practice, only guidelines, a kind of default that we’ve found nature tends to follow when it’s feeling co-operative. Murphy’s Law, however, really is a law. An absolute, unbreakable rule. And that’s final.

But Murphy’s Law is only one side, the pessimistic side, of something that is more wide-ranging. Engineers are paid to be cautious, after all. So Murphy’s Law has an opposite, a more optimistic side, one that is better known in the magical tradition and elsewhere: we could call it Nasruddin’s Law, perhaps, after the eccentric hero of Idries Shah’s well-known Sufi tales. And it’s equally simple: “if something can go right, it probably will – if you let it – and usually in the most unexpected way”.

The trouble with Nasruddin’s Law is that it is completely anarchic and completely eclectic. Anything goes, anything and nothing is true, there is no definable cause or effect, just a sense that ‘things happen because they happen to happen’. To get it to work for you, you have to allow absolutely everything in. Fishing for facts, if you like, or the ones you want will swim away downstream and hide. Somewhere in an endless mass of information, all of it happening now and somewhen, somewhere: all of it coincidences, events. A meaningless morass – except that somehow you want to extract meaning from it, extract the facts you need to find.

In effect what we’re saying in using a pendulum is that we don’t care how the information arrives – from what source, physical or otherwise, or via what channel or mechanism, physical or otherwise. All we care about is that the right piece of information should arrive. And that it should show itself by provoking a specific reflex twitch in the arm that’s holding the pendulum, so that it shows up as a pendulum response that we’ve previously defined as Yes or No or some other recognisable interpretation.

We don’t care at all what the mechanism shall be: we invoke Nasruddin’s Law, without trying, and see what we get. We get what we get – all coincidence, of course. But what it means depends on the context: it depends on us. The rules that define meaning are not defined in someone else’s ‘laws of nature’, but are up to us.

Which can be disturbing, even frightening at times: to get the pendulum to work well, you’re scratching at the surface of a suddenly uncertain world, a world in which everything and nothing is true at the same time, a world in which things can be both real and imaginary at the same time.

So the world’s uncertain: so what’s new? The only thing that is certain is uncertainty; the only constant is change itself, and even that isn’t constant. We use explanations to try to pin things down to a certainty, only to have them get up and play peek-a-boo with us just for the fun of it. The real and the imaginary become blurred, confused; yet it’s there, where everything is coincidence and mostly imaginary, that we can do the most.

Imaging – “imaginary worlds”

A classic mistake, encouraged by school-level ideas about reality, is to take the physical world that we can touch and smell and see to be the only way in which things can be real. It’s such a pervasive part of our training in our culture’s assumptions that it’s not easy to see that it is only an assumption, rather than something which is absolute, fixed, real. For example, it’s often a mistake to ask about something “Is it real or imaginary?” Because, once again, the answer’s usually “Yes”. Both. At the same time: not real or imaginary, but real and imaginary. Real – but in an imaginary sense.

Watch a dog or a cat sleeping. Suddenly, still fast asleep, its paws twitch, its claws come out, it makes little running movements. It’s hunting, it’s seen prey – in its dreams. Entirely imaginary – yet real at the same time, otherwise you wouldn’t see the effects. It’s not your dream, after all. But if the cat’s sleeping in your lap, its claws will be all too real as they sink themselves into your leg!

Let’s take another example. Imagine an orange. It’s floating just above these pages. (All right, so oranges don’t usually float in mid-air, but this one can: it’s imaginary, it doesn’t have to obey the law of gravity). Look at it. Look at its colour, its texture. Look at the label they put on it in the imaginary shop you imagined you bought it from. Reach out and touch it; feel its texture, its weight, its scent. Give it a squeeze: feel it yield slightly. Now dig your fingernails in: mind that the juice doesn’t hit you in the eye! And now you can smell it, too. Strip the peel away. And break off a segment. Put the segment in your mouth: rest it on the tip of your tongue, like a small neatly-wrapped parcel, tasting of nothing much. Now bite on it… and as the juice bursts into your mouth, now you taste it!

Except it’s entirely imaginary.

Yet you felt it, smelt it, tasted it.

Sensed it in a way that we could record and measure physically.

So it’s real.

Real and imaginary.

At the same time.

Fine. So things can be real and imaginary. Very interesting. So what’s the use, you ask.

The answer is that that’s how we can set up the context so that the pendulum’s responses can be meaningful. We build a complete image of what we’re looking for; then, coincidentally, we find it. Entirely coincidence; mostly imaginary. That’s how I described dowsing earlier: now it should be starting to make sense, even if it didn’t before.

In a sense, we’re playing with sympathetic magic again. We say the pendulum responds in ‘sympathy’ to the coincidence between what we’re looking for and where we are. Without needing to worry about a connection or a cause. And both of those – what we’re looking for and where we are – are defined, in part at least, in an imaginary way.

Normally we say we ‘are’ where we’re standing, where we’re sitting: in other words we define our position physically. But if someone interrupts me when I’m thinking, I might well say “Sorry, I was miles away” – and in an imaginary sense that’s entirely true. I may have been here physically, but my thoughts were miles away, I was imagining a place miles away.

Take a practical example. I’ll assume that you’re sitting down at the moment. Now, without getting up from your chair, imagine that you’re walking out through the door. (It sometimes helps to close your eyes to do this, but then you couldn’t be reading this at the same time… perhaps). Look around you as you do so: what can you see? Looking through your mind’s eye.

In imagination, walk on out into the street. Build an image of that street. Recall the image of it as you last saw it; then feel what it’s like now rather than then. Watch the traffic go by. Hear the traffic go by, the chatter of people and birds, the world outside in the street; sense it, smell it, feel it. Go to the shop where you imagined you bought that imaginary orange; look around in there, sense around in there. You can, with practice, move about freely in this imaginary world, collecting information just as you would if you were physically there.

Which you’re not.

It’s all in your mind’s eye.

All imaginary.

And real.

At the same time.

Imagination. Image-ination. Building images.

An imaginary world that’s real enough to collect information from.

Information that could be of use.

Does anything stand out at the moment? Is there anything that’s different, odd; something trying to say Hello?

Fishing for facts.

Watching, sensing; letting the world talk to us instead of us talking at the world.

It’s that sensing that we’re using in working with a pendulum. Building an imaginary world, letting the answers arise and show themselves, through the movements of the pendulum. In a sense what we’re doing is using something close to a ritual to switch into a state in which we’re looking in an imaginary world, fishing for facts, for information that could be of use. Using the pendulum to say ‘look at this piece of information’ — not so much an extra-sensory tool as an extra sensing tool that combines and links the senses together. Imaginary senses as well as ‘real’, physical ones.

The trick is to link the imaginary worlds to the physical one: literally real-ising the imaginary world, making it real. Without that coincidence of worlds, the coincidence of the pendulum’s reaction is meaningless – ‘a mere coincidence’ – because there’s nothing you can hang meaning on. The pendulum’s response will be exactly correct, perhaps, but only in an imaginary world and not in this physical one in which everyone else exists as well. Merging imaginary worlds: another nice piece of mental acrobatics!

The other side of this is to prime yourself to recognise a specific coincidence – to tune yourself like a radio, so to speak. An everyday example might be when you buy a new car: you hadn’t seen this model before, but now that you’ve bought it, suddenly they’re everywhere. In fact they probably were there before, but you weren’t primed to see them: so you didn’t see them, or rather didn’t perceive them. But now the coincidence has some meaning – “it’s the same car as mine!” – so it stands out as ‘signal’ from the rest of the background noise of information. The result is that you can see it – although it looks like it’s something new that’s happening.

To illustrate this and to put the two sides together, let’s play with a classic piece of modern practical magic: finding a free parking space on the street in the city. Sure: finding a needle in a haystack might be easier. The game depends entirely on how you approach it, and is a little like the old joke: “You can have three wishes – anything you want – but if you should ever even think of the word ‘hippopotamus’ everything you gain from them will disappear”. Now: you mustn’t think ‘hippopotamus’. What do you mean, you couldn’t not think of it?

What we’re trying to do here is imagine that someone will drive away from a parking meter just as we arrive. If you don’t imagine it, it won’t happen (or it may, but you probably won’t see it, because you’re not primed to expect to see it). If you try to imagine it, trying harder and harder, it will happen in an imaginary world, perhaps, but not in this world your car is in: knowing Murphy’s Law, what you’ll probably get instead of a parking space is a not-so-imaginary parking ticket. What you need to do is just imagine it; build an image of it happening; let it happen. And notice that it’s happened – look, that man there’s pulling out now. But perhaps it won’t work if you think of the word ‘hippopotamus’…

If you don’t imagine it, nothing happens; if you try too hard, nothing happens. Just somewhere in between is a tiny place in which Murphy’s Law gives way to Nasruddin’s Law; in which things happen, crazily, miraculously, irregularly, irreverently. Coincidences. They happen all the time. The trick is to notice them, to allow ourselves to see them as they happen. And to do that is like looking at that dim star at night: to see the parking space, the coincidence we’re looking for, we have to flounder around trying to look for it by not looking at it, in order to get a better view of it. Strange.

It’s not just strange: it’s crazy, insane.

It just happens to be the way the world works.

So what kind of a joke is that?

Meet the Joker

School-science has its law of gravity. Everything is grave, everything is serious; everything is known (by the schoolteachers and television pundits at least), everything is predictable, everything fits the rules. And you’d better fit the rules, too. If that’s your view of the world, meet the Joker. He’s in charge of the law of levity: nothing is serious, perhaps, although everything is serious too, at the same time. And his rules say that nothing is absolutely known, nothing is absolutely predictable, and there are no absolute rules for things to fit.

Except for one absolute rule: which we see on one side as Murphy’s Law, on another as Nasruddin’s Law.

He has a very strange sense of humour: but then you’ll have seen that if you’ve watched Murphy’s Law in action. Quirky; anarchic; the whole point is that it is unpredictable.

In a way, though, it’s all too easy to predict when the unpredictable will occur. It occurs almost without fail when you take things too seriously; when you’re too certain that you’re right. Especially if you’re working outside of the so-safe confines of school-level reality.

That school-level reality defines little more than a cardboard world, a fake unreality which excludes vast areas of our experience, in the real world we know. But that greater reality is a crazy world, in which the key character plays practical jokes at whim. Not exactly helpful, but that’s the way the world is. Especially if you’re learning to use the pendulum to look at that world, to learn about that world. Because as soon as you think you’re certain about anything, certain about how something really works, up comes the Joker: and suddenly, and often embarrassingly, things aren’t so certain any more.

(I call it the Joker because that’s what it feels like: perhaps it’s more accurate, though, to say that it’s us making fools of ourselves in trying to lay limitations on something that isn’t anything like as limited as we are!)

The magical tradition is more used to such things than most. There’s the Fool of the Tarot; the character ‘Youthful Folly’ of the I Ching; Jung’s ‘Trickster’ archetype; to say nothing of the menagerie of ‘non-human mischievous sprites’, to quote a recent Church formal report on exorcism. “The Devil, that prowde spirit, cannot bear to be mocked”, said Thomas More. In this sense the Devil is not the Church’s fanciful guy with horns, but an aspect of us: our own pride, our own certainty. If you haven’t much of a sense of humour, cultivate one. Now. Urgently. You’ll need it!

But you don’t need to think too much about all this. In fact, in another of these bizarre jokes, it’s best not to think about it at all. Just pretend that that school-level reality is all there is. Forget the rest. Know it’s there, but forget it; let it brew away on its own. Thinking about it will drive you crazy: but then you must be crazy already to be using a pendulum at all, surely?

What’s the use?

That’s enough wandering in the background realms for a while. End of play-time, time to put it to use.

Except that it’s never the end of play-time: unless you don’t mind being the butt-end of one of the Joker’s unfunny practical jokes.

Serious play, then.

Because the pendulum’s only useful if you can put it to use.

So let’s move on to find some practical uses for the thing; move on to look at how to use it in practice.

Before we look at techniques and the like, we need to look a little more at what we mean by ‘use’. Working with a pendulum, we are, if you like, working in a magical world, one in which matters of respect and balance are perhaps more immediately important than they are in the more conventional realms of greed and push-and-shove. Because there is this little problem which most people seem to prefer to shove to one side and forget: and that’s a question of ethics.

Don’t panic: I’m not going to wander off into some long moralistic tirade. It’s more like the practical experience of an engineer. There are certain things you don’t do if you want your railway bridge to stay up: you don’t use low-grade materials, you don’t allow shoddy workmanship, you don’t skimp on safety checks and quality control. Reality doesn’t allow you to cheat. Otherwise, all too soon, you’ve an expensive wreck on your hands, and some difficult explanations to invent.

The same is true of the pendulum: you’ve got to get it right, but to get it right you have to be able to sneak into that gap between nothing and Murphy’s Law. It’s a delicate balance. One you won’t be able to maintain, for example, if you’re thinking about tomorrow night’s party or what you’re going to spend the profit on, rather than keeping your mind on the job. You have to beware – literally, ‘be aware’ – of what you’re doing now, of the context of the questions you’re asking and answering, all of the time that you’re working. And, in principle, all the time you’re not working, too.

There’s another aspect to balance. Everything you do and everyone else does has its effects: whether you had marmalade for breakfast on Tuesday, and whether it’s raining now in Guatemala, all have their impact in this crazy world in which everything is somehow interlinked without being linked at all. That means that you have to be cautious about what you do: you can’t just barge in and grab. And that’s practical experience, not spurious moralising. Look at some magicians of fiction: the sorcerer’s apprentice in Fantasia, or Ursula le Guin’s character Sparrowhawk in her Earthsea Trilogy. Then realise that they’re not so fictional…

The Joker will be quite happy to oblige in assisting you in folly… with the joke on you.

A little humility is a useful asset in using a pendulum.

So is a little awareness of when you’re about to put your foot in something that you’d rather you didn’t!

So: how do you learn to be aware that you’re not aware? More mental acrobatics?

There are ways – an infinite number. The right one for you is the one that works for you: only you will know which one it is. But one standard approach is to make things into a ritual, a fixed sequence – and then watch for ‘holes’ in the sequence. That’s why so much pendulum work looks like inane ritual: because that’s precisely what it is. Childish ritual; a game. A game with a purpose: putting a game to use.

The point about ritual is not so much in the content of the ritual as in its use as a tool to point out what’s missing. There’s nothing odd about this: rituals are used in every technology, although few people seem keen to admit that that’s what they are. For example, it’s forty years since I flew light aircraft in the school cadets, but I still remember the standard formal phrases that we had to recite out loud as safety checks: “throttle closed, switches off” before priming the engine, “all clear above and behind” before a glider launch, “you have control” before handing over in a dual-control rig. Or keywords like ‘hasel’: meaningless in itself, but it’s an acronym of a check-list — ‘height, airspeed, straps, engine, lookout’ — used as a safety mnemonic before starting an aerobatic sequence. Incantations in some high-tech mystical rite, with automatic, barely-conscious responses. But we noticed straight away if anything was missing: that’s what they were for. Built up from practical experience to emphasise practical experience, to prevent stupid – and dangerous – mistakes.

In the same vein it’s useful to build a standard ritual to use with your pendulum to check that you’re not about to make some stupid mistake. One of the most common is American dowser Sig Lonegren’s check-list: “This is what I want to dowse. Can I? May I? Am I ready?” The dowser’s equivalent of the pilot’s pre-take- off check.

You could use it like a programmer’s flow-chart:

Step one:

Decide what you want to look for, and state to the pendulum, “This is what I want to dowse”.

Step two:

Holding the pendulum, ask “Can I use the pendulum now?” (Context: do I have the skill to do this particular dowsing operation; am I in a fit condition now; am I capable now?)

If no (or indecisive), stop; otherwise proceed to step three.

Step three:

Holding the pendulum, ask “May I use the pendulum now?” (Context: are the conditions – unspecified – suitable to proceed; is it safe to proceed?)

If yes, proceed to step four; otherwise stop.

Step four:

Holding the pendulum, ask “Am I ready?” (Context: am I ready to proceed now?)

If no, stop; otherwise proceed to use the pendulum for whatever you want to go on to do.

End of sequence.

A checklist; a pre-take-off check.

Since we’re about to move on to look at techniques, try it now: Can I? May I? Am I ready?

If any of the answers are No, it doesn’t mean that you can’t do it at all; it just means that you shouldn’t do it now. If that’s so, now’s the time to take a break.

But you’ll probably need that now in any case; and when you’ve rested, I’ll see you in the next chapter!