2 Getting started

Choosing a pendulum

Before you can use a pendulum, you first need to have one to hand. Obviously.

In mechanical terms, the ideal pendulum should be a small symmetrical weight, preferably almost spherical but with a point at the base, and with a thread mounted through the centre of its top. It should balance well at the end of its thread; it should not wander around when you swing it back and forth.

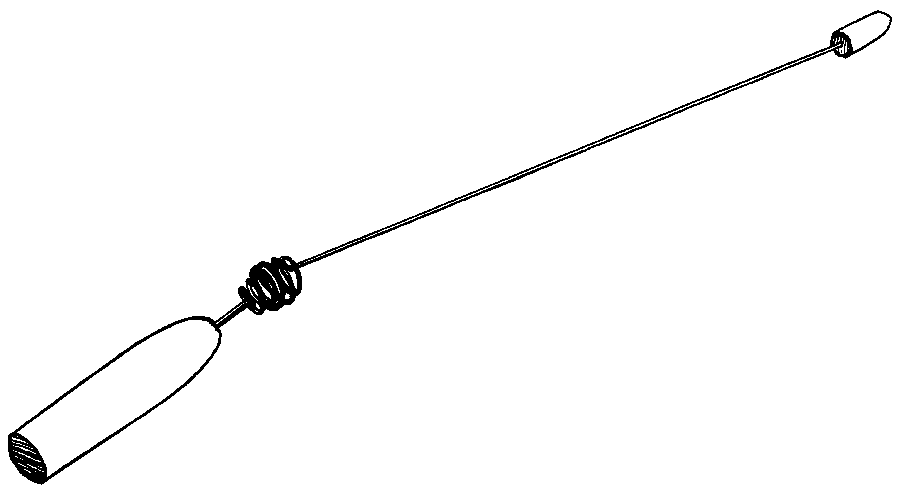

Many ‘alternative’ or ‘New Age’ shops can sell you ready-made pendulums that match this ideal: beautiful crystals, finely engineered bronze or silver bobs, or purpose-built map-dowsing pendulums on a length of chain. And in addition to simple bobs there are oddities like the ‘Pasquini Amplifying Pendulum’ with its hollow handle and tiny weight on the end of a spring, looking like a miniature version of a fencer’s foil; or the Cameron Aurameter, which is spring-loaded to swing from side to side rather than up and down; and many others, of course. And all of these come with price tags to match.

The Pasquini Pendulum

But you can just as easily make it yourself. It doesn’t have to be ideal, and it doesn’t need to be anything special: the one I used for my first experiments, as a teenager, was a wooden soldier from the toy-box with a match rammed into the top to hold a length of thread in place. Its balance was awful, but it worked well enough. You can use almost anything you can swing from your hand: I’ve even used a bunch of keys, or a bathplug on a chain. All it has to do is swing freely and easily from your hand. As long as it doesn’t get tangled up with itself or blown about in the wind, it’ll probably do.

In a way, though, perhaps it does need to be something special: special as far as you’re concerned. As with any craftsman’s toolkit, a pendulum can become something more than a mere tool: something highly personal, rather, that seems to take on its own character. Part of the magic, perhaps. A trinket, like the plastic white elephant I mentioned earlier; a pendant; a crucifix or an ankh; it may be nothing like the ‘ideal pendulum’ but it’s something more than just a ‘thing’ to you, more almost a part of you. A minor overdose of magic might not be too bad an idea here: if something feels right to play with as a pendulum, it probably is.

Holding a pendulum

Once you have in hand your ring-on-a-string or its equivalent, you have to hold it in such as way that it can swing freely back and forth. Otherwise it won’t, or rather can’t, do anything.

Hold the thread between forefinger and thumb (either hand will do). Don’t drape the thread over your finger: hold it with your hand pointing down, and the thread hanging straight down, rather as you would hold a somewhat distasteful worm. The thread should typically be about four to six inches from your fingertips to the top of the bob (‘lose’ the rest of the thread by wrapping it round your other fingers – don’t let it dangle down to get tangled up with the pendulum). Again, this isn’t a hard and fast rule – there aren’t any hard and fast rules – but simply a way that works well for most people. Do it any other way and the pendulum will probably wander about as you use it, simply for mechanical reasons: but if you don’t feel comfortable with the way I’ve suggested, that’s fine too. In any case, you should certainly experiment with different ways of holding the thing as you play with it, to see what works best for you: it’s your pendulum, not mine, after all.

Before we move on, there’s a small side-issue we could look at: the question of length. In some books on dowsing, such as Tom Lethbridge’s delightful series, the length of the thread is meant to be used to select what you’re looking for: the so-called ‘long pendulum’ system. If you’ve read about that, fine, but skip it for now, and we’ll come back to it later. Right now it’s simpler to stick to the ‘short pendulum’ approach. Where the length does matter to us here is in the balance of the pendulum – a heavier bob usually needs a longer thread of six inches or so, especially if it’s used outdoors, whereas a lightweight one may need little more than an inch or two. It should feel comfortable and balanced as it swings in your hand; it should feel as if it’s moving of its own accord without any help from you. But that’s something you’ll find out from experiment, from practice, from experience. Theory is there if you need it, but it takes a back seat to whatever feels right for you at the time.

Using a pendulum: the basics

After all that, we now at last we come to using the thing. Well, almost. There’s one last point that we have to get clear. And that is that the pendulum does exactly what you tell it to. It moves because your hand moves. Your hand moves as a reflex response to something. It moves because you tell it to, consciously, unconsciously or otherwise. It does not do anything on its own: it’s not apart from you, it’s a part of you.

Like a computer program, it does exactly what you tell it to, and nothing else. In effect, you program its responses. You program your hand to set up those responses. Like the computer program, what those responses mean depends on the program, depends on the context of the program. It can’t actually go wrong, for the simple reason that there’s nothing to it that can go wrong. What can go wrong is what you told it to do.

In theory at least, the computer programs I write can never go wrong, can never themselves make a mistake, because the machine can only do what I tell it to do. But I can very easily make mistakes in writing that program, so that I get responses that make no sense at all. “This program’s done exactly what I told it to do: so what on earth did I tell it to do?” The same is true of using a pendulum: “This pendulum’s given me exactly the response I asked for: so what on earth did I ask it?” As I said earlier, getting an answer is easy: it’s framing questions that’s hard…

What we’re doing with a pendulum is using it to give a framework for reflex responses to questions, in much the same way as you train your feet to respond to danger in a car. Hitting the brake is – or should be – an entirely reflex response; but it’s a learned reflex response. And one that works best when it finally becomes unconscious, automatic, rather than something we have to think about each time we drive a car. So the same is true of a pendulum: it’s a learned reflex response, and one that works best when we forget that it’s there. In other words, it’s a skill, a skill we learn through practice, not through theory. Which brings us back to practice again.

Keep talking

Despite my insistence that the pendulum does exactly what you tell it to, I’m now going to insist that it doesn’t. In other words we tell ourselves that it works of its own accord, without our conscious involvement at all. That way we can use it to personify our un_conscious responses to questions: the problem with unconscious responses is that they _are unconscious, so we need some way of bringing them out into the open, so to speak, to make them visible so that we can see what they are. And that’s what we can use the pendulum for: to make the unconscious visible, or rather as a crutch to learn how to recognise the unconscious for what it is.

So a simple trick is to talk to the pendulum, as if it had a mind of its own, as if it were separate from us. Which it does and is. And which it doesn’t and isn’t. At the same time. (I did warn you about some mental acrobatics! But don’t worry, it doesn’t have to make sense yet…).

Talk to your pendulum. Treat it as a household pet. It may have the personality of a slightly cantankerous child; you may need to cajole it, entreat it at times to give you the results you need. It may need a certain amount of house-training, to learn the rules of the house: that Yes means Yes, and No means No. And both of you will need to learn mutual respect. You can’t force it to give you the results you want, but it will always give you the results you need: just remember that sometimes what you might really need is an embarrassing blunder or two… So just keep talking.

Talking to your pendulum is also talking to yourself. Yes, it’s slightly crazy; but so what? I work in a computer environment where half the time people are cursing at their programs trying to cajole them into working the way they want them to, muttering away to themselves and their screens: and that’s just as usual and certainly no more crazy than talking to a pendulum. Much the same thing, actually. It’s crazy, and perhaps a little inelegant, but it works; and that’s really what matters.

Keep it moving

It’s difficult to move if you can only stand still. In the same way, it’s easier to watch the movements of a pendulum if it’s already moving. So, again, if you’ve read books on dowsing that say you should hold your pendulum still and wait for a response, fine; but note that for simple mechanical reasons (called inertia) you may wait so long that the response has given up and gone home by the time the pendulum actually gets a chance to move.

So swing the pendulum gently backwards and forwards. Like a clock pendulum, ticking away the time. And perhaps watch it as you might watch a clock that’s an hour or two away from lunch: out of the corner of your eye, with a little hopefulness, rather than full-blooded clock-watching.

Think of that gentle to-and-fro swing as a ‘neutral’ position. Nothing much happening. Nothing to report. Watch it like the hypnotist’s watch – to and fro, to and fro. A neutral state.

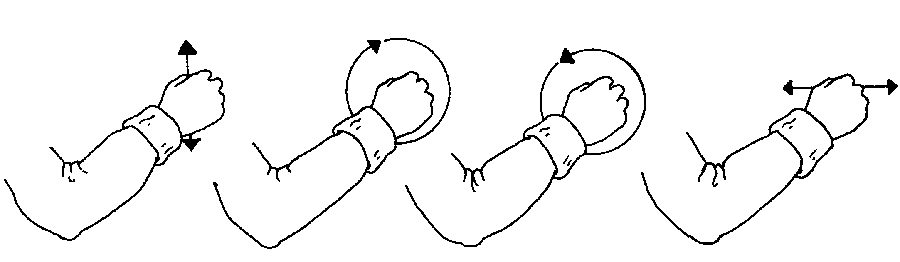

From that state it can move to other states. The swing can move like a compass arm, pointing out a direction. And back again. Or it can change from a simple swing to a gyration, round and round; one way; back to neutral; the other way; back to neutral again.

Try it. Or rather watch it: don’t try. Just do it. Let the pendulum move by itself, reflecting what you’re thinking about. The pendulum, after all, does exactly what you tell it to do, since, as an extension of your arm, it’s an extension of you: so swing it back and forth, and then let it go through those changes of movement, as if by itself. Knowing that it’s part of you, that it’s you doing it; and that it feels like it’s moving of its own accord. That’s when this little ring-on-a-string starts to become a pendulum, something you can use to look at yourself and elsewhere.

Yes and no

The next stage is to set up a meaning for responses: at the moment, these wanderings of a pendulum are completely meaningless. All we have at the moment are something we call ‘neutral’ and various other movements: so we need to set up some rules to say what they mean.

Note that you set up the rules. There are no other rules. Except that that also includes the rules which you set up but don’t know about. Like telling yourself it can’t mean anything anyway. And all the other hidden rules that you might use to convince yourself that you can’t do anything new, or different, or unscientific, or in any way out of the ordinary. Actually, you can. Just add the hidden rules that tell you you can do it, rather than those rules that tell you you can’t.

Be positive (and negative, for that matter). State what meaning those movements are going to have. Tell your pendulum (in other words yourself) what the rules should be.

Program the pendulum, just like programming a computer: give it a set of rules to follow.

Try the nice-guy method first. Hold the pendulum in whichever hand feels the most comfortable with it. Swing your pendulum gently to and fro. And ask it for a movement which means Yes. Politely.

Then ask it to go back to neutral.

Now ask for a No. Any movement that will regularly mean No.

And ask it to go back to neutral again.

(If you aren’t doing this, you should be: otherwise none of this will ever make sense).

Right. Try it again. Go through the whole cycle once more. Yes; neutral; No; neutral.

That’s it. That’s just about all there is to operating a pendulum.

Not exactly complicated, really.

All right, so it didn’t make sense, it wasn’t consistent. What did you expect: miracles? But if it really feels like the pendulum isn’t going to play, make some rules: don’t just ask it, tell it. For example, here’s one instant set of rules: With the pendulum in your right hand, a change from a neutral to-and-fro to a clockwise gyration is Yes. A change from neutral to a counter-clockwise movement is No. That’s the rules. (Or, if you prefer, any other rules you feel happier with: it’s your choice, remember).

If it insists on doing something else regularly, that’s also the rules. In fact a better set of rules. Come to an agreement between you and the pendulum as to what the rules are. And make sure that both of you stick to them. You’ve got to live with each other, work with each other: find a way to make it easy for both of you, without you giving up and going away in disgust.

Yes, I know that this personifying of a lump of metal is crazy. I know that it’s you on both sides of this discussion. It’s just that this is an easy way of you tricking you into co- operating with you in ways that perhaps you haven’t done before, to get at information that you almost certainly haven’t been able to get at before, simply because you couldn’t see it before. By playing this rather childish game, you can; later you can learn to do it without this charade and simply know. But that takes practice: something you haven’t had yet. Just go along with this for a while. Play. Have fun. (End of pep-talk that was probably quite unnecessary because everything’s working just fine for you anyway).

With clear and recognisable responses for neutral, Yes and No, you can ask the pendulum questions. (More accurately, ask yourself questions, but we’ve been through that a few times already). And then get responses that you can actually interpret as meaning something. The catch is: what questions?

Questions, questions

This type of dowsing is entirely about questions and answers: any questions. Any questions, as long as they can meaningfully be answered by Yes or No. Questions about anything. Which is why some writers on dowsing have presented it as some kind of universal panacea: “the pendulum answers every question!” Well, yes: except that a lot of the questions you could ask, like “should I wake up this morning”, do seem a trifle dumb and stupid; and other questions aren’t all that suitable in a system which can only answer Yes or No.

It’s the same as people expecting a computer somehow to arrive miraculously with an answer to every question – even if it isn’t designed for the purpose, or programmed that way. The acronym ‘GIGO’, or “garbage in, garbage out”, is engraved very early on in every programmer’s mind. A computer simply does what it is told, with the information it has available, and answers in the only ways it has available to it; and that’s all. The same is true of using a pendulum: it’s not exactly helpful if, in response to the question “What do I do now”, the pendulum can only answer Yes. Or No.

So the trick is not so much the answers – they’re easy, as we’ve seen – as in asking questions. The right questions. Except, by some Kafka-esque logic, you won’t necessarily know what questions you’ve asked; and you won’t know what the right question is until you’ve already found it. Fishing for facts. Hunting, pursuing, stalking a question. Letting each question and its answer lead on to the next question and its answer.

Almost all teaching in schools and colleges is still based on the idea of “Here’s a question – What’s the answer?”; and usually with the implicit aside of “We already know the answer, and that’s the one you’re supposed to guess to get good grades”. But what we’ve got here, as is true of every real skill, is something more like “Here’s this answer – so what on earth was the question?” Tricky, that. We’ll keep on coming back to that as we go along.

The importance of the idiot

The big problem with a system that can only answer Yes or No is that it can’t tell you when the question can’t be answered by Yes or No. It can only answer Yes. Or No. Or perhaps say nothing at all, which is equally unhelpful. And leaves you feeling pretty foolish, and probably annoyed, too.

The pendulum can only answer Yes or No – or Idiot

All of which leaves you in the position where you can’t see what’s wrong. Like the infuriated schoolteacher after yet another interruption, you’re saying “Every time I open my mouth some fool speaks!” You can’t see what’s wrong, because there’s no way in the system to see what’s wrong. It wasn’t built in.

This is where I have been known to get irritated at some other writers on dowsing, who present a rigid system which has only Yes, No and Neutral, with no space for anything else. And with no space, no alternative, no way to recognise that you’ve presented some dumb question, you’ll be left stuck. Very stuck.

This ‘space’, which I call the ‘Idiot’ response because it occurs when I’ve been an idiot, is essential to any working system. The equivalent in computer programming is the routines and sub-programs that look out for errors while a program is running: perhaps the most difficult part to write of any program, because you’ve got to think of every possible error that might occur. And even then there’s always something that slips through: there’s a popular adage among programmers that says “As soon as you think you’ve made your program idiot-proof, along comes a better idiot”.

Idiot. Un-ask the question, is what it means. This question can’t be answered meaningfully by Yes or No: un-ask the question.

The way I use a pendulum, the movement that means ‘Idiot’ is a side-to-side swing, in other words at right-angles to Neutral. Check for yourself what that would be: try some stupid question like “What do I do now?” and see what response you would get. If you don’t get a regular response, try the side-to-side one; change it later if it doesn’t feel right. It’s up to you, remember.

Neutral; Yes; No; Idiot. It wouldn’t be complete, wouldn’t be usable, without the idiot, the ‘wise fool’. Which is you. And me. Of course.