Operating Systems

An operating system is software that manages computer hardware and software resources for computer applications. For example Microsoft Windows could be the operating system that will allow the browser application Firefox to run on our desktop computer.

Variations on the Linux operating system are the most popular on our Raspberry Pi. We will examine several different Linux distributions that are designed to work in different ways.

Linux is a computer operating system that is can be distributed as free and open-source software. The defining component of Linux is the Linux kernel, an operating system kernel first released on 5 October 1991 by Linus Torvalds.

Linux was originally developed as a free operating system for Intel x86-based personal computers. It has since been made available to a huge range of computer hardware platforms and is a leading operating system on servers, mainframe computers and supercomputers. Linux also runs on embedded systems, which are devices whose operating system is typically built into the firmware and is highly tailored to the system; this includes mobile phones, tablet computers, network routers, facility automation controls, televisions and video game consoles. Android, the most widely used operating system for tablets and smart-phones, is built on top of the Linux kernel. In our case we will be using a version of Linux that is assembled to run on the ARM CPU architecture used in the Raspberry Pi.

The development of Linux is one of the most prominent examples of free and open-source software collaboration. Typically, Linux is packaged in a form known as a Linux distribution, for both desktop and server use. Popular mainstream Linux distributions include Debian, Ubuntu and the commercial Red Hat Enterprise Linux. Linux distributions include the Linux kernel, supporting utilities and libraries and usually a large amount of application software to carry out the distribution’s intended use.

A distribution intended to run as a server may omit all graphical desktop environments from the standard install, and instead include other software to set up and operate a solution stack such as LAMP (Linux, Apache, MySQL and PHP). Because Linux is freely re-distributable, anyone may create a distribution for any intended use.

Sourcing and Setting Up

On our desktop machine we are going to download the image (*.img) files for each distribution and write it onto a MicroSD card. This will then be installed into the Raspberry Pi.

Downloading

We should always try to download our image files from the authoritative source and we can normally do so in a couple of different ways. We can download via bit torrent or directly as a zip file, but whatever method is used we should eventually be left with an ‘img’ file for our distribution.

To ensure that the projects we work on can be used with the full range of Raspberry Pi models (especially the B2) we need to make sure that the versions of the image files we download are from 2015-01-13 or later. Earlier downloads will not support the more modern CPU of the B2.

Writing the Operating System image to the SD Card

Once we have an image file we need to get it onto our SD card.

We will work through an example using Windows 7, but for guidance on other options (Linux or Mac OS) raspberrypi.org has some great descriptions of the processes here.

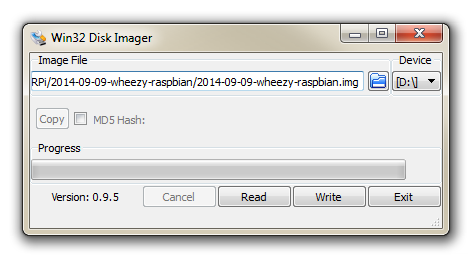

We will use the Open Source utility Win32DiskImager which is available from sourceforge. This program allows us to install our disk image onto our SD card. Download and install Win32DiskImager.

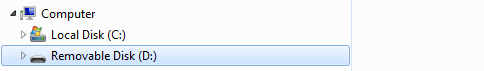

You will need an SD card reader capable of accepting your MicroSD card (you may require an adapter or have a reader built into your desktop or laptop). Place the card in the reader and you should see a drive letter appear in Windows Explorer that corresponds with the SD card.

Start the Win32 Disk Imager program.

Select the correct drive letter for your SD card (make sure it’s the right one) and the disk image file that you downloaded. Then select ‘Write’ and the disk imager will write the image to the SD card. It can vary a little, but it should only take about 3-4 minutes with a class 10 SD card.

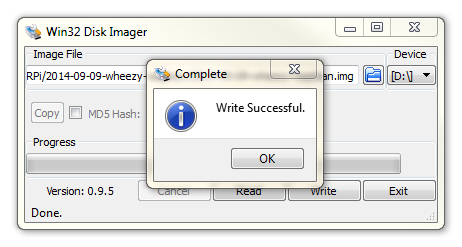

Once the process is finished exit the disk imager and eject the card from the computer and we’re done.

Welcome to Raspbian (Debian Wheezy / Jessie)

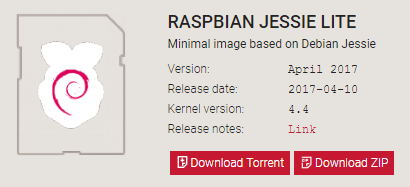

The Raspbian Linux distribution is based on Debian Linux. There have been two different editions published. ‘Wheezy’ and ‘Jessie’. Debian is a widely used Linux distribution that allows Raspbian users to leverage a huge quantity of community based experience in using and configuring software. The Wheezy edition is the earlier of the two and was been the stock edition from the inception of the Raspberry Pi till the end of 2015. From that point Jessie has become the default distribution used. Be aware that they can operate differently when being used from the command line. Instructions for both are included in the book, but Jessie is the default.

Downloading

The best place to source the latest version of the Raspbian Operating System is to go to the raspberrypi.org page; http://www.raspberrypi.org/downloads/.

You can download via bit torrent or directly as a zip file, but whatever the method you should eventually be left with an ‘img’ file for Raspbian.

To ensure that the projects we work on can be used with either the B+ or B2 models we need to make sure that the version of Raspbian we download is from 2015-01-13 or later. Earlier downloads will not support the more modern CPU of the B2.

Installing Raspbian

Make sure that you’ve completed the previous section on downloading and loading the image file and have a Raspbian disk image written to a MicroSD card. Insert the card into the slot on the Raspberry Pi and turn on the power.

You will see a range of information scrolling up the screen before eventually being presented with one of three screens;

- If you are using Wheezy you should be presented with the Raspberry Pi Software Configuration Tool.

- If you are using the full Jessie distribution we will go straight to a GUI desktop

- If you have installed the ‘lite’ Jessie edition you will go to a login prompt.

The ‘Jessie Lite’ Command Line interface

If you have installed Jessie Lite, when you first boot up the process should automatically re-size the root file system to make full use of the space available on your SD card. If this isn’t the case, no need to worry as the facility to do it can be accessed from the Raspberry Pi configuration tool.

Once the reboot is complete (if it occurs) you will be presented with the console prompt to log on;

The default username and password is:

Username: pi

Password: raspberry

Enter the username and password.

Congratulations, you have a working Raspberry Pi and are ready to start getting into the thick of things!

Firstly we’ll do a bit of house keeping.

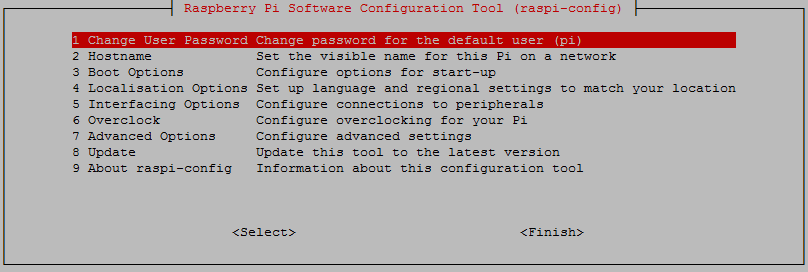

Raspberry Pi Software Configuration Tool

As mentioned earlier, if we weren’t prompted to use the Raspberry Pi Software Configuration Tool we should run it now to enable full use of the storage on the SD card and changes in the locale and keyboard configuration as well as enabling ssh (more on that later). This can be done by running the following command;

Use the up and down arrow keys to move the highlighted section to the selection you want to make then press tab to highlight the <Select> option (or <Finish> if you’ve finished).

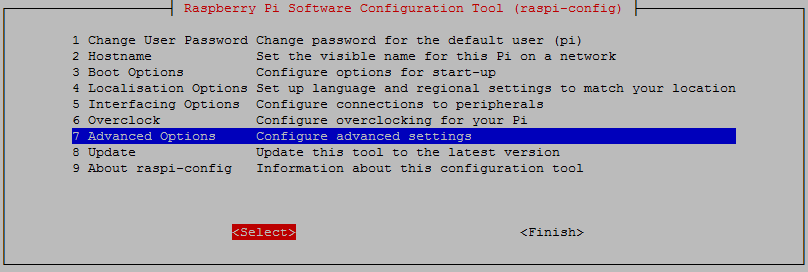

If you didn’t see the file system expanded on the SD card on first boot, select ‘7 Advanced Options’;

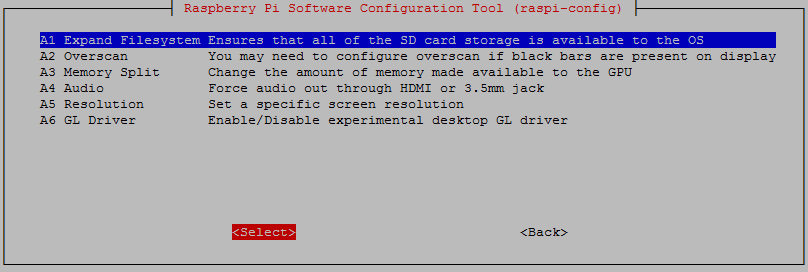

Then ‘A2 Expand Filesystem’;

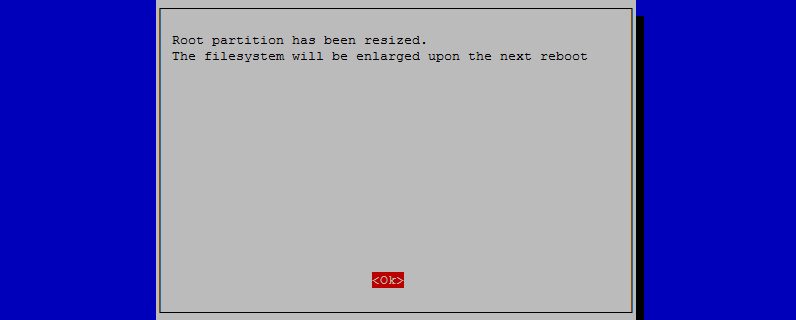

Once selected there will be a dialogue box that will tell us that the changes will be enabled on the next boot.

Once this has been completed we can continue to configure other options safe in the knowledge that when we reboot the Pi we will have the use of the full capacity of the SD card.

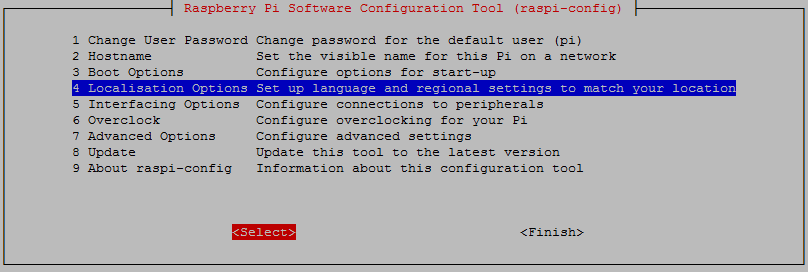

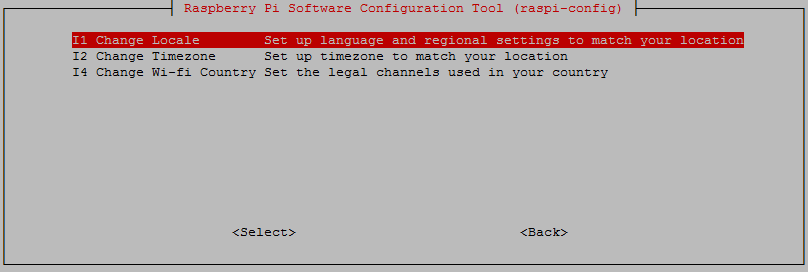

While we are here it would probably be a good idea to change the settings for our operating system to reflect our location for the purposes of having the correct time, language and WiFi regulations. These can all be located via selection ‘4 Localisation Options’ on the main menu.

Select this and work through any changes that are required for your installation based on geography.

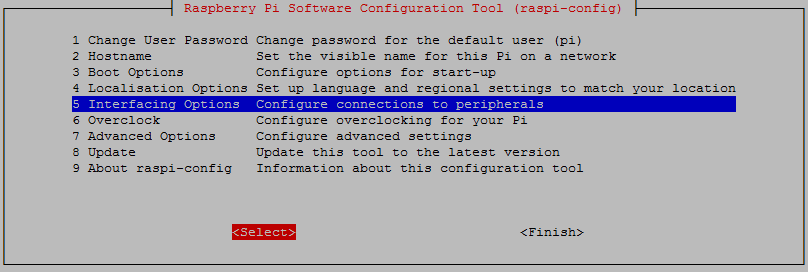

The last main menu item that is worth considering is to enable remote access via ssh. This will allow us to access the Raspberry Pi on our local network via a desktop computer or laptop, removing the need to have a keyboard and monitor connected directly to the Pi. More on the options available here are in the Remote Access section. To enable this select ‘5 Interfacing Options’ from the main menu.

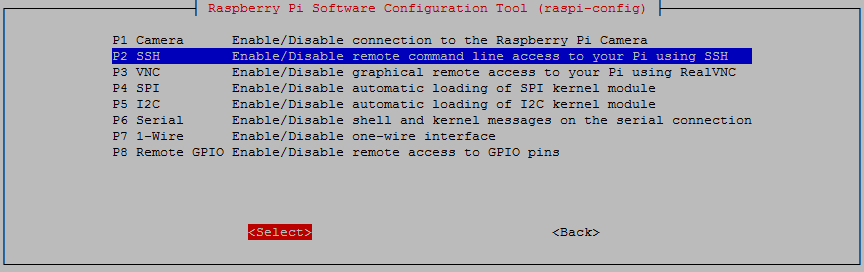

From here we select ‘P2 SSH’

ssh used to be enabled by default, but doing so presents a potential security concern, so it has been disabled by default as of the end of 2016.

Once you exit out of the raspi-config menu system, if you have made a few changes, there is a probability that you will be asked if you want to re-boot the Pi. That’s a pretty good idea.

Once the reboot is complete you will be presented with the console prompt to log on again;

Software Updates

After configuring our Pi we’ll want to make sure that we have the latest software for our system. This is a useful thing to do as it allows any additional improvements to the software we will be using to be enhanced or security of the operating system to be improved. This is probably a good time to mention that we will need to have an Internet connection available.

Type in the following line which will find the latest lists of available software;

You should see a list of text scroll up while the Pi is downloading the latest information.

Then we want to upgrade our software to latest versions from those lists using;

The Pi should tell you the lists of packages that it has identified as suitable for an upgrade and along with the amount of data that will be downloaded and the space that will be used on the system. It will then ask you to confirm that you want to go ahead. Tell it ‘Y’ and we will see another list of details as it heads off downloading software and installing it.

(The sudo portion of the command makes sure that you will have the permission required to run the apt-get process.

GUI Desktop

If you have installed Raspbian Jessie with Pixel, when you first boot up the software should automatically re-size the root file system to make full use of the space available on your SD card. It will show a short screen telling you that it has done it and that it is rebooting for the changes to take effect. Once the reboot is complete you should find yourself successfully logged into the ‘Pixel’ graphical desktop.

Running a GUI environment is a burden to the computer. It takes a certain degree of computing effort to maintain the graphical interface, so as a matter of course we should only use a desktop GUI when absolutely necessary.

Welcome to OpenELEC

OpenELEC is an operating system built around Kodi. Kodi is a free and open source (GPL) software media center for playing videos, music, pictures and games. It was formerly known as XBMC and is widely regarded as a leading project in the media player world.

OpenELEC operates as a Home Theatre and, is designed to be as lightweight as possible in terms of size, complexity and ease of use. Because of it’s simplicity, it is capable of operating on platforms such as the Raspberry Pi and providing excellent value for money. This also means that we can install our media centre in a very small space and it can be totally silent.

Downloading

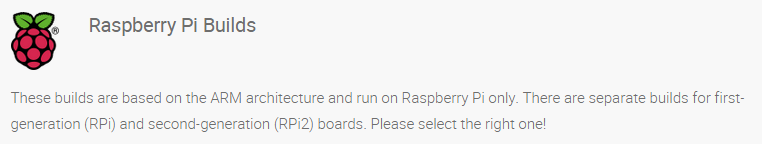

The best place to source the latest version of the OpenELEC Operating System is to go to the raspberrypi.tv page; http://openelec.tv/get-openelec. There are a range of different types of computers that the operating system is configured for and part way down the page we will come across seperate download options for either the classic Raspberry Pi models (A, A+, B and B+) or the newer Raspberry Pi 2 Model B.

We can also select between a stable version of the software (for the more conservative amongst us) or the latest ‘Beta’ version which may have more cutting edge features, but may not have been tested as fully. Either way it’s a safe bet since the download is free :-). There is also the option to download an ‘Update file’ or an ‘image’. The ‘Update file’ is available to allow people to manually update existing installations. The ‘image’ file is for new instals. Since this will be the first time that we’re installing the software we will want to go for the ‘image’ file.

the file we download is compressed (zipped) so we will want to use our favourite unzipping program to extract the contents and then we should be left with our ‘img’ file.

Installing OpenELEC

Make sure that you’ve completed the previous section on downloading and loading the image file and have a OpenELEC disk image written to a MicroSD card. Insert the card into the slot on the Raspberry Pi and turn on the power.

The system will automatically resize the amount of storage space that it uses on the MicroSD card to use the available capacity and then it will reboot.

Once it reboots we will be presented with a series of screens that allow us to configure the install ready for use.

- Firstly we select the language

- Then the hostname which is the name that the device will identify itself with on the network when configuring things like file sharing services.

- Then it will let us know what networks the Pi is connected to so that we can select one for streaming content like YouTube and for updating the operating system.

- Then we are asked what sharing and remote access options we would like to use. SSH is probably unnecessary for new users, but Samba may be useful for those who want to share their content from their OpenELEC box onto their home network

- Finally we have a thank you page that will lead us to the interface itself.

That’s it! You’re installed and ready to start exploring OpenELEC and enjoying one of the best media center applications available.

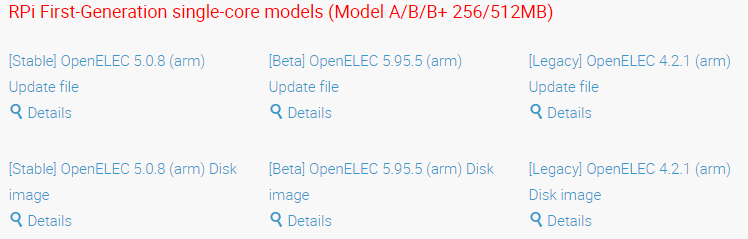

To make a start using OpenELEC, you can follow your nose and simply see what happens with the various set up options availabel or even (heaven forbid) read the extensive help pages available on the Kodi Wiki.

Welcome to Ubuntu

Ubuntu is one of, if not the, largest deployed Linux based desktop operating systems in the world. Linux is at the heart of Ubuntu and makes it possible to create secure, powerful and versatile operating systems.

Ubuntu is available in a number of different flavours, each coming with its own desktop environment. Ubuntu MATE takes the Ubuntu base operating system and adds the MATE Desktop. The MATE Desktop Environment is the continuation of another desktop called GNOME 2. It includes a file manager which can connect you to your local and networked files, a text editor, calculator, archive manager, image viewer, document viewer, system monitor and terminal. All of which are highly customisable and managed via a control centre.

But wait… There’s more…

While the MATE Desktop provides the essential user interfaces to control and use a computer, Ubuntu MATE adds a collection of additional applications to turn your computer into a truly powerful workstation. These include The Firefox web browser, the Thunderbird email client, the LibreOffice productivity suite that is Microsoft Office compatible, Rhythmbox for playing and organising music, Shotwell for organising your digital photos and VLC for playing multimedia. All of these applications are Open Source and freely available for you to use.

There is a small catch….

The price of being able to run a desktop operating system that can provide access to the same set of applications and a similar experience to a far larger and more expensive computer is that we can’t use the slightly older Raspberry Pi 1 machines (the A, A+, B and B+). Only the Raspberry Pi 2 with its ARMv7-based BCM2709 processor is able to run the software. The good news is that it does a pretty good job!

It’s a really good idea to use a Class 10 MicroSD card that will provide a much faster access to the data and thus improve the user experience.

We will also want to use a card that is 8GB or larger so that we have some space for the operating system to store a little bit of information. Technically it will survive on 4GB, but don’t cut it short if you don’t need to.

Downloading

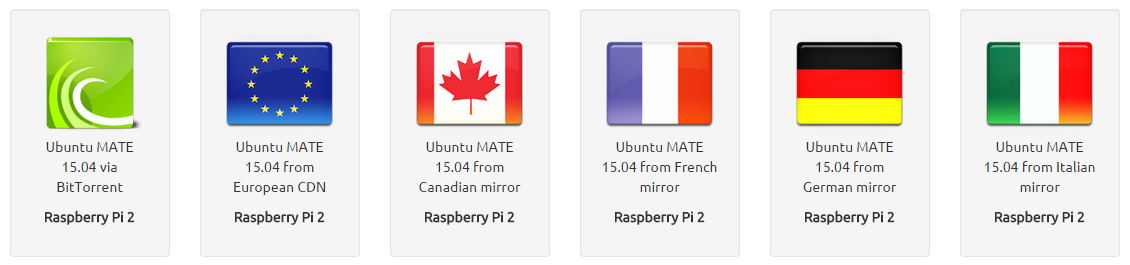

The best place to source the latest version of the Ubuntu MATE Operating System is to go to the ubuntu-mate.org page; https://ubuntu-mate.org/raspberry-pi/. There are a range of different download locations and the option to use Bit Torrent (which is a useful option to reduce stress on the servers kindly provided by those who support the project).

The file we download is compressed (zipped) so we will want to use our favourite unzipping program to extract the contents and then we should be left with our ‘img’ file.

Installing Ubuntu

Make sure that you’ve completed the previous section on downloading and loading the image file and have a Ubuntu MATE disk image written to a MicroSD card. Insert the card into the slot on the Raspberry Pi 2 and turn on the power.

Initially there will be some scrolling text with a slight pause for 15 seconds or so before a splash screen appears;

This will stay on the screen for about 20 seconds until we are presented with a screen where we can select the language we will use.

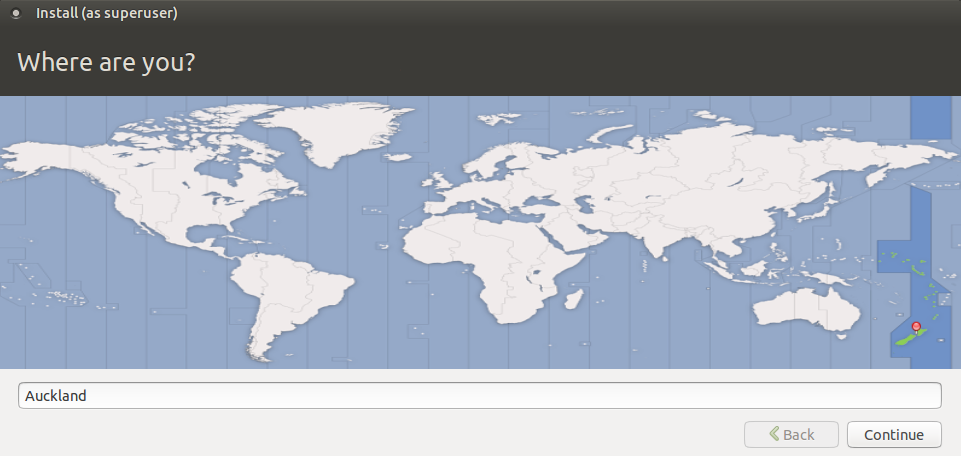

Then we select our location which will determine the time on our system as well as the default locale settings;

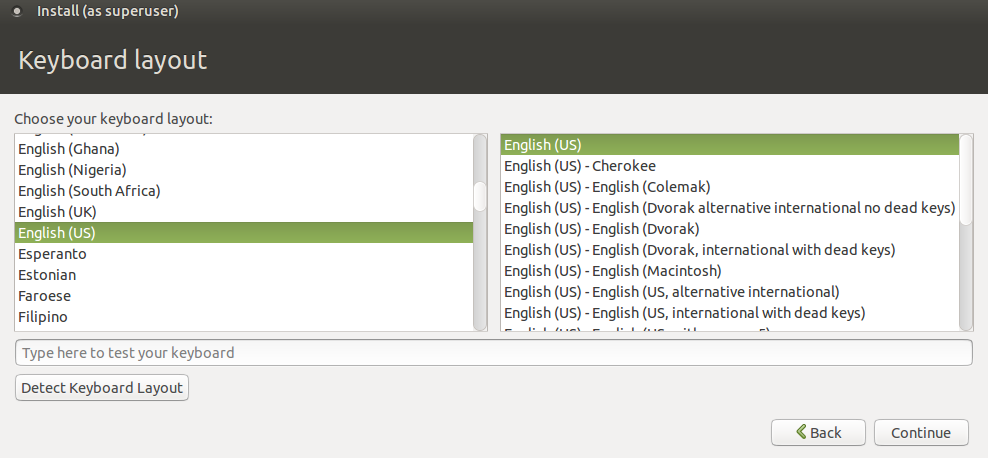

Then we select the keyboard layout. The system should be clever enough at this stage to know from your language and locale settings to make an educated guess, but because there are a wide range of keyboard options irrespective of your location or language, we get to choose :-).

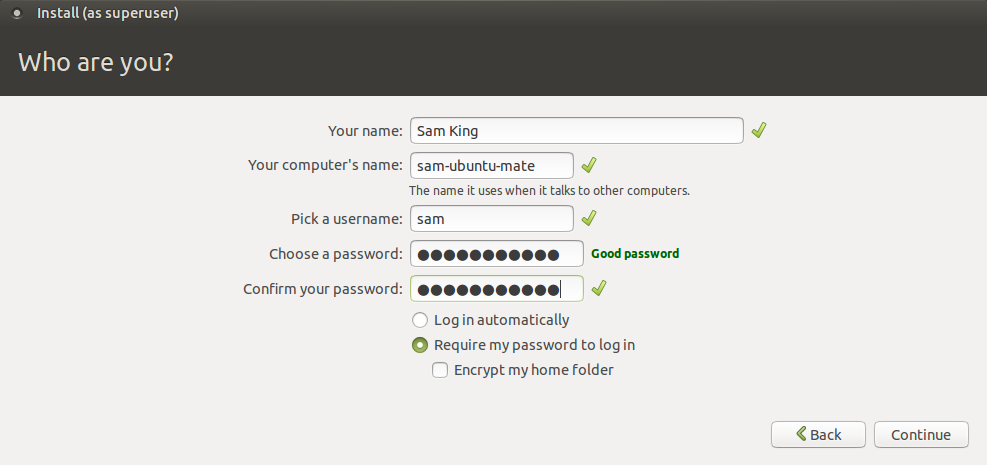

Then we get to enter our user details. The computer will kindly let you know how good it considers your password to be (in other words, the more difficult to guess, the better it thinks it will be).

Once our user is set up the computer will configure itself based on our selections and apply the changes it needs to make to the installation. This will take something like 8 minutes and then we’re up and running!