Inheritance, Ontologies, and Semantic Types

Class Hierarchies

In theory, JavaScript does not have classes. It has “prototypes,” and it is always entertaining to lurk in a programming forum and watch people debate the exact definition of the word “class” in computer science, and then debate whether JavaScript has them. We’ve been careful to use the word “metaobject” in this book, mostly because “metaobject” isn’t encumbered with baggage such as the instanceof keyword or specific rules about inheritance and creation of instances.

In practice, the following snippet of code is widely considered to be an example of a “class” in JavaScript:

function Account () {

this._currentBalance = 0;

}

Account.prototype.balance = function () {

return this._currentBalance;

}

Account.prototype.deposit = function (howMuch) {

this._currentBalance = this._currentBalance + howMuch;

return this;

}

// ...

var account = new Account();

The pattern can be extended to provide the notion of subclassing:

function ChequingAccount () {

Account.call(this);

}

ChequingAccount.prototype = Object.create(Account.prototype);

ChequingAccount.prototype.sufficientFunds = function (cheque) {

return this._currentBalance >= cheque.amount();

}

ChequingAccount.prototype.process = function (cheque) {

this._currentBalance = this._currentBalance - cheque.amount();

return this;

}

We’ve been calling this pattern “Delegating to Prototypes,” but let’s call them classes and subclasses so that we can align our investigation with popular literature. These “classes and subclasses” provide most of the features of classes we find in languages like Smalltalk:

- Classes are responsible for creating objects and initializing them with properties (like the current balance);

- Classes are responsible for and “own” methods, Objects delegate method handling to their classes (and superclasses);

- Methods directly manipulate an object’s properties.

Smalltalk was, of course, invented forty years ago. In those forty years, we’ve learned a lot about what works and what doesn’t work in object-oriented programming. Unfortunately, this pattern celebrates the things that don’t work, and glosses over or omits the things that work.

the semantic problem with hierarchies

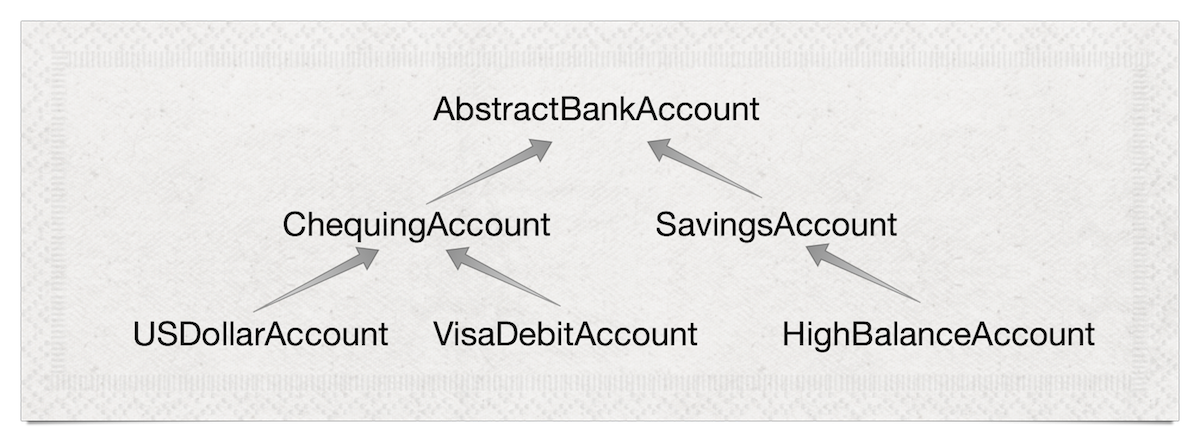

At a semantic level, classes are the building blocks of an ontology. This is often formalized in a diagram:

The idea behind class-based OO is to classify (note the word) our knowledge about objects into a tree. At the top is the most general knowledge about all objects, and as we travel down the tree, we get more and more specific knowledge about specific classes of objects, e.g. objects representing Visa Debit accounts.

Only, the real world doesn’t work that way. It really doesn’t work that way. In morphology, for example, we have penguins, birds that swim. And the bat, a mammal that flies. And monotremes like the platypus, an animal that lays eggs but nurses its young with milk.

It turns out that our knowledge of the behaviour of non-trivial domains (like morphology or banking) does not classify into a nice tree, it forms a directed acyclic graph. Or if we are to stay in the metaphor, it’s a thicket.

Furthermore, the idea of building software on top of a tree-shaped ontology would be suspect even if our knowledge fit neatly into a tree. Ontologies are not used to build the real world, they are used to describe it from observation. As we learn more, we are constantly updating our ontology, sometimes moving everything around.

In software, this is incredibly destructive: Moving everything around breaks everything. In the real world, the humble Platypus does not care if we rearrange the ontology, because we didn’t use the ontology to build Australia, just to describe what we found there. If we started by thinking that Platypus must be a flightless Avian, then later decide that it is a monotreme, we aren’t disturbing any platypi at all with our rearranging the ontology. Whereas with classes and subclasses, if we rearrange our hierarchy, we are going to have to break and then mend our existing code.

It’s sensible to build an ontology from observation of things like bank accounts. That kind of ontology is useful for writing requirements, use cases, tests, and so on. But that doesn’t mean that it’s useful for writing the code that implements bank accounts.

Class Hierarchies are often the wrong semantic model, and the wisdom of forty years of experience with them is that there are better ways to compose programs.

how does encapsulation help?

As we’ve discussed repeatedly, naïve classes suffer from open recursion. An enormous amount of coupling takes place between classes in a class hierarchy when each class has full access to an object’s properties through the this keyword. In Encapsulation for MetaObjects, we looked at one possible way to isolate classes from each other, reducing the amount of coupling.

If coupling is dramatically reduced through the use of techniques like encapsulation, we can look at a class hierarchy strictly as an exercise in getting the semantics correct.

Getting the Semantics Right

Let’s talk about modeling students at a university. Here are a few things we might need to model:

- Students pursue a degree

programsuch as “Pre-Med,” “Law,” “Pharmacy,” or “Nursing.” - Students attend on a part-time or full-time

schedule.

Should there be a Student class? Certainly. What about subclassing Student with PreMedStudent, LawStudent, PharamcyStudent, and NursingStudent? We use these terms in everyday speech, and there are certain behaviours we expect to differ between them. Furthermore, we can expect that we do not have a “many-to-many” relationship between students and programs.

And yet, we could also set up the program as a “has-a” relationship. Maybe each Student has a program property, and delegates behaviour to its program.

Likewise… PartTime and FullTime are disjoint, a student is one or the other but not both. So we could have a PartTimeStudent and a FullTimeStudent. But what if we decide that we also want to have PreMedStudent, LawStudent, PharamcyStudent, and NursingStudent? Are we supposed to set up a two-level hierarchy, with classes like PartTimeNursingStudent and a FullTimeNursingStudent both delegating to NursingStudent, and NursingStudent delegating to Student?

And why not the other way around, e.g. PharmacyPartTimeStudent and NursingPartTimeStudent both delegating to PartTimeStudent that in turn delegates to Student? or likewise, why not make schedule a property, and delegate behaviour to it so that each Student has-a Schedule?

This a strong hint that the program and schedule behaviours should not be placed in a hierarchy with each other: They seem to be peers. They could be implemented by composing metaobjects into prototypes or with delegation to properties.

Now let’s consider this entirely made-up case, salespeople in a company:

- There are inside and outside salespeople.

- Inside salespeople work on Major Accounts or Small/Medium Business (“SMB”)

- Outside salespeople sell to all customers.

- Inside salespeople sell the full range of products.

- Outside salespeople sell electronic components, computer peripherals, or test equipment.

Now there is a natural hierarchy:

- Salesperson

- InsideSalesperson

- MajorAccountsInsideSalesperson

- SmallMediumBusinessInsideSalesperson

- OutsideSalesperson

- ElectronicComponentsOutsideSalesperson

- ComputerPeripheralsOutsideSalesperson

- TestEquipmentOutsideSalesperson

- InsideSalesperson

This follows from the fact that the variations on an inside salesperson are disjoint from the variations on an outside salesperson. Does this mean that we must organize prototypes into a “class hierarchy?” Not necessarily. There are two major factors affecting our choice:

First, ease of rearrangement vs. likelihood of needing to rearrange: Even with encapsulation, class hierarchies are inflexible relative to composing metaobjects or delegating to properties. That can be a good thing, in that it acts as a road-bump against someone accidentally implementing a MajorAccountsOutsideSalesperson, and it does make our understanding of the constraints of the domain very discoverable in the code.

Second, invariance of class over the lifetime of an entity. Do salespeople move between inside and out? From SMB to Major Accounts? Changing classes is relatively rare in OOP style. In the current release of JavaScript, changing an object’s prototype is unevenly supported, unexpected by programmers, and incurs a heavy performance penalty. It’s usually easier to make a new entity with a new prototype chain that is otherwise a copy of the old entity, or to model something we expect to change as a state machine: If people tend to remain as inside or outside salespeople, but change between Major Accounts and SMB more often, we could model the accountType as a property and delegate or forward behaviour to it.

Ultimately, class hierarchies do make semantic sense for some portions of the behaviour we need to model, but we need to consider the semantics carefully and not try to force everything to fit into a hierarchy. Those things that naturally fit can benefit from being modelled as classes, those that do not should be modelled in another way.

Circling back to our fundamental idea, this is why it is important to (a) Have multiple ways to model behaviour with metaobjects, and (b) design our metaobject protocols (encapsulate, composition, delegation, and so forth) to be compatible with each other. The flexibility of mixing and matching state machines, delegation to properties, composing mixins, and prototype chains permits us to design software that is simpler to read, write, and refactor as needed.

Structural vs. Semantic Typing

A long-cherished principle of dynamic languages is that programs employ “Duck” or “Structural” typing. So we can write a “class” like this:

function CurrentAccount () {

this._amount = {

dollars: 0,

cents: 0

}

}

CurrentAccount.prototype.amount = function (optionalAmount) {

if (optionalAmount === undefined)

return this._amount;

else this._amount = {

dollars: optionalAmount.dollars,

cents: optionalAmount.cents

};

}

function Cheque (amount, date) {

this._amount = amount,

this._date = date;

}

Cheque.prototype.amount = function () {

return this._amount;

}

function MoneyOrder (amount, number) {

this._amount = amount,

this._number = number;

}

Cheque.prototype.amount = function () {

return this._amount;

}

function depositInstrument (account, instrument) {

var newAmount = {

dollars: account.amount().dollars + instrument.amount().dollars;

cents: account.amount().cents + instrument.amount().cents;

};

newAmount.dollars += Math.floor(newAmount.cents / 100);

newAmount.cents = newAmount.cents % 100;

account.amount(newAmount);

}

This works for things that look like cheques, and for things that look like money orders:

var acct = new CurrentAccount(),

cheque = new Cheque({ dollars: 100, cents: 0 }, new Date()),

moneyOrder = new MoneyOrder({ dollars: 200, cents: 0 }, 6);

depositInstrument(acct, cheque);

depositInstrument(acct, moneyOrder);

The general idea here is that as long as we pass depositInstrument an instrument that has an amount() method, the function will work. We can imagine that any object with an amount() method is has a “type,” even if we don’t give the type a name like hasAnAmount. Programming in a dynamic language like JavaScript is programming in a world where there is a many-many relationship between types and entities.

Further to this, every single function that takes a parameter and uses only its amount() method is a function that requires a parameter of type hasAnAmount.

There is no checking of this in advance, like some other languages. That doesn’t mean we can’t check this in advance, languages like ML and Haskell have no problem “inferring” types from their usage.

This business of writing code and having functions just use it helps flexibility: It encourages the creation of small, independent pieces work seamlessly together. Having written code that works for cheques, it’s easy to use the same code with money orders.

drawbacks

This flexibility has a cost. With our ridiculously simple example above, we can easy deposit new kinds of instruments. But we can also do things like this:

function TaxesOwed (amount) {

this._amount = amount;

}

TaxesOwed.prototype.amount = function (optionalAmount) {

if (optionalAmount === undefined)

return this._amount;

else this._amount = {

dollars: optionalAmount.dollars,

cents: optionalAmount.cents

};

}

var backTaxesOwed = new TaxesOwed({

dollars: 10,874,

cents: 06

});

function Receipt (amount, date, description) {

this._amount = amount;

this._date = date;

this._description = description;

}

Receipt.prototype.amount = function () {

return this._amount;

}

var rentReceipt = new Receipt({ dollars: 420, cents: 0 }, new Date(), "July Rent\

");

depositInstrument(backTaxesOwed, rentReceipt);

Structurally, depositInstrument is compatible with any two things that have account() methods. But not all things that ave account() methods are semantically appropriate for deposits. This is why some OO language communities work very hard developing and using type systems that incorporate semantics.

This is not just a theoretical concern. Numbers and strings are the ultimate in semantic-free data types. Confusing metric with imperial measures is thought to have caused the loss of the Mars Climate Orbiter. To prevent mistakes like this in software, forcing values to have compatible semantics–and not just superficially compatible structure–is thought to help create self-documenting code and to surface bugs.

semantic methods

We see above that there is a weakness with writing functions that deposit money into anything that has an amount() function. Many things that have an amount() function are not “depositable” and/or may not “accept deposits.”

In a structural, “duck typed” language, we must is to work at a higher level of abstraction. Why does the function depositInstrument directly manipulate the dollars and cents of amounts? We have some very good arguments against this from a coupling point of view, but we can now see a semantic argument against it: Lots of things have amounts.

So let’s revisit how to deposit amounts:

function Cheque (amount, number) {

this.amount = {

dollars: amount.dollars,

cents: amount.cents

};

this.number = number;

}

Cheque.prototype.depositableAmount = function () {

return this.amount;

}

function SavingsAccount (initialBalance) {

this.amount = {

dollars: initialBalance.dollars,

cents: initialBalance.cents

};

}

SavingsAccount.deposit = function (amountOfDeposit) {

this.amount.dollars += amountOfDeposit.dollars;

this.amount.cents += amountOfDeposit.cents;

this.amount.dollars += Math.floor(this.account.cents / 100);

this.amount.cents = this.account.cents % 100;

return this;

}

What matters here is that we’re defining the semantic methods depositableAmount and deposit. Now we can write:

function depositInstrument (account, instrument) {

return account.deposit(instrument.depositableAmount());

}

We can add lots of other functionality like marking that a depositable instrument has been negotiated and so on. But the key point here is that we aren’t testing whether an account is-a AcceptsDeposits, we’re checking whether an account implements deposit. Likewise, we don’t care whether an instrument is-a Depositable, we care whether it implements depositableAmount.

Thus, we can later create something like this credit-card that is backed by an account. You can make deposits directly against it at an ATM:

function AccountBackedCard (account) {

this.account = account;

}

AccountBackedCard.prototype.deposit = function (amountOfDeposit) {

this.account.deposit(amountOfDeposit);

return this;

}

An AccountBackedCard has no inheritance relationship to an account, but you can deposit funds into it, and the funds are deposited to the underlying account. We’ve replaced the notion of semantic “types” with the notion of semantic “interfaces.”

We avoid the problem of depositing a rent receipt into a statement of back taxes owed by ensuring that whatever entity we use to represent a rent receipt does not have a depositableAmount method, and ensuring that whatever entity we use to represent the amount of back taxes owed does not have a deposit method.

If we have a TaxesOwed entity, we wouldn’t want to use a deposit method to increase it. Instead, we’d use a method like addPenalty. Although the code for addPenalty might look identical to the code for deposit, the are different semantically.

In practice, choosing semantically meaningful methods and avoiding structurally meaningful methods (like .add)

Interlude: “is-a” and “was-a”

Words like “delegate” are carefully chosen to say nothing about semantic relationships. Given:

function C () {}

C.prototype.iAm = function () { return "a C"; };

var a = new C();

a.iAm();

//=> 'a C'

a instanceof C

//=> true

We can say that the entity a delegates handling of the method iAm to its prototype. But what is the relationship between a and C? What is this “instance of?”

In programming, there are two major kinds relationships between entities and metaobjects (be those metaobjects mixins, classes, prototypes, or anything else). First, there is a semantic relationship. We call this is-a. If we say that a is-a C, we are saying that there is some valuable meaning to the idea that there is a set of all Cs and that a belonging to that set matters.

The second is an implementation relationship. We have various names for this depending on how we implement things. We can say a delegates-to C. We can say a uses C. We sometimes arrange things so that a is-composed-of mixin M.

When we have an implementation relationship, we are saying that there is no meaningful set of entities, the relationship is purely one of convenience. Sometimes, we use physical inheritance, like a prototype, but we don’t care about a semantic relationship, it’s simply a mechanism for sharing some behaviour.

When we use inheritance but don’t care about semantics, we call the relationship was-a. a was-a C means that we are not asserting that it is meaningful to say that a is a member of the set of all Cs.

Semantic typing is all about “is-a,” whereas structural typing is all about “was-a.”

The Expression Problem

The Expression Problem is a programming design challenge: Given two orthogonal concerns of equal importance, how do we express our programming solution in such a way that neither concern becomes secondary?

An example given in the c2 wiki concerns a set of shapes (circle, square) and a set of calculations on those shapes (circumference, area). We could write this using metaobjects:

var Square = encapsulate({

constructor: function (length) {

this.length = length;

},

circumference: function () {

return this.length * 4;

},

area: function () {

return this.length * this.length;

}

});

var Circle = encapsulate({

constructor: function (radius) {

this.radius = radius;

},

circumference: function () {

return Math.PI * 2.0 * this.radius;

},

area: function () {

return Math.PI * this.radius * this.radius;

}

});

Or functions on structs:

function Struct () {

var name = arguments[0],

keys = [].slice.call(arguments, 1),

constructor = eval("(function "+name+"(argument) { return initialize.call(\

this, argument); })");

function initialize (argument) {

var struct = this;

keys.forEach(function (key) {

Object.defineProperty(struct, key, {

enumerable: true,

writable: true,

value: argument[key]

});

});

return Object.preventExtensions(struct);

};

return constructor;

}

var Square = Struct('Square', 'length');

var Circle = Struct('Circle', 'radius');

function circumference(shape) {

if (Square(shape)) {

return shape.length * 4;

}

else if (Circle(shape)) {

return Math.PI * 2.0 * this.radius;

}

}

function area (shape) {

if (Square(shape)) {

return this.length * this.length;

}

else if (Circle(shape)) {

return Math.PI * this.radius * this.radius;

}

}

Both of these operations make one thing a first-class citizen and the the other a second-class citizen. The object solution makes shapes first-class, and operations second-class. The function solution makes operations first-class, and shapes second-class. We can see this by adding new functionality:

- If we add a new shape (e.f.

Triangle), it’s easy with the object solution: Everything you need to know about a triangle goes in one place. But it’s hard with the function solution: We have to carefully add a case to each function covering triangles. - If we add a new operation, (e.g.

boundingBoxreturns the smallest square that encloses the shape), it’s easy with the function solution: we add a new function and make sure it has a case for each kind of shape. But it’s hard with the object solution: We have to make sure that we add a new method to each object.

In a simple (two objects and two methods) example, the expression problem does not seem like much of a stumbling block. But imagine we are operating at scale, with a hierarchy of classes that have methods at every level of the ontology. Adding new operations can be messy, especially in a language that does not have type checking to make sure we cover all of the appropriate cases.

And the functions-first approach is equally messy in contemporary software. It’s a very sensible technique when we program with a handful of canonical data structures and want to make many operations on those data structures. This is why, despite decades of attempts to write Object-Relational Mapping libraries, PL/SQL is not going away. Given a slowly-changing database schema, it’s far easier to write a new procedure that operates across tables, than to try to write methods on objects representing a single entity in a table.

dispatches from space

There’s a related problem. Consider some kind of game involving meteors that fall from the sky towards the Earth. You have fighters of some kind that fly around and try to shoot the meteors. We have an established way of handling a meteors hitting the Earth or a fighter flying into the ground and crashing: We write a .hitsGround() method for meteors and for fighters.

WHenever something hits the ground, we invoke its .hitsGround() method, and it handles the rest. A fighter hitting the ground will cost so many victory points and trigger a certain animation. A meteor hitting the ground will cost a different number of victory points and trigger a different animation.

And it’s easy to add new kinds of things that can hit the ground. As long as they implement .hitsGround(), we’re good. Each object knows what to do.

This resembles encapsulation, but it’s actually called ad hoc polymorphism. It’s not an object hiding its state from tampering, it’s an object hiding its semantic type from the code that uses it. Fighters and meteors both have the same structural type, but different semantic types and different behaviour.

“Standard” OO, as practiced by Smalltalk and its descendants on down to JavaScript, makes heavy use of polymorphism. The mechanism is known as single dispatch because given an expression like a.b(c,d), The choice of method to invoke given the method b is made based on a single receiver, a. The identities of c and d are irrelevant to choosing the code to handle the method invocation.

Single-dispatch handles crashing into the ground brilliantly. It also handles things like adjusting the balance of a bank account brilliantly. But not everything fits the single dispatch model.

Consider a fighter crashing into a meteor. Or another fighter. Or a meteor crashing into a fighter. Or a meteor crashing into another meteor. If we write a method like .crashInto(otherObject), then right away we have an anti-pattern, there are things that ought to be symmetrical, but we’re forcing an asymmetry on them. This is vaguely like forcing class A to extend B because we don’t have a convenient way to compose metaobjects.

In languages with no other option, we’re forced to do things like have one object’s method know an extraordinary amount of information about another object. For example, if a fighter’s .crashInto(otherObject) method can handle crashing into meteors, we’re imbuing fighters with knowledge about meteors.

double dispatch

Over time, various ways to handle this problem with single dispatch have arisen. One way is to have a polymorphic method invoke another object’s polymorphic methods. For example:

var FighterPrototype = {

crashInto: function (otherObject) {

this.collide();

otherObject.collide();

this.destroyYourself();

otherObject.destroyYourself();

},

collide: function () {

// ...

},

destroyYourself: function () {

// ...

}

}

In this scheme, each object knows how to collide and how to destroy itself. So a fighter doesn’t have to know about meteors, just to trust that they implement .collide() and .destroyYourself(). Of course, this presupposes that a collisions between objects can be subdivided into independant behaviour.

What if, for example, we have special scoring for ramming a meteor, or perhaps a sarcastic message to display? What if meteors are unharmed if they hit a fighter but shatter into fragments if they hit each other?

A pattern for handling this is called double-dispatch. It is a little more elegant in manifestly typed languages than in dynamically typed languages, but such superficial elegance is simply masking some underlyin issues. Here’s how we could implement collisions with special cases:

var FighterPrototype = {

crashInto: function (objectThatCrashesIntoFighters) {

return objectThatCrashesIntoFighters.isStruckByAFighter(this)

},

isStruckByAFighter: function (fighter) {

// handle fighter-fighter collisions

},

isStruckByAMeteor: function (meteor) {

// handle fighter-meteor collisions

}

}

var MeteorPrototype = {

crashInto: function (objectThatCrashesIntoMeteors) {

return objectThatCrashesIntoMeteors.isStruckByAMeteor(this)

},

isStruckByAFighter: function (fighter) {

// handle meteor-fighter collisions

},

isStruckByAMeteor: function (meteor) {

// handle meteor-meteor collisions

}

}

var someFighter = Object.create(FighterPrototype),

someMeteor = Object.create(MeteorPrototype);

someFighter.crashInto(someMeteor);

In this scheme, when we call someFighter.crashInto(someMeteor), FighterPrototype.crashInto invokes someMeteor.isStruckByAFighter(someFighter), and that handles the specific case of a meteor being struck by a fighter.

To make this work, both fighters and meteors need to know about each other. They are coupled. And as we add more types of objects (observation balloons? missiles? clouds? bolts of lightning?), our changes must be spread across our prototypes. It is obvious that this system is highly inflexible. The principle of messages and encapsulation is ignored, we are simply using JavaScript’s method dispatch system to achieve a result, rather than modeling entities.

Generally speaking, double dispatch is considered a red flag. Sometimes it’s the best technique to use, but often it’s a sign that we have chosen the wrong abstractions.

Multiple Dispatch

In The Expression Problem, we saw that JavaScript’s single-dispatch system made it difficult to model interactions that varied on two (or more) semantic types. Our example was modeling collisions between fighters and meteors, where we want to have different outcomes depending upon whether a fighter or a meteor collided with another fighter or a meteor.

Languages such as Common Lisp bake support for this problem right in, by supporting multiple dispatch. With multiple dispatch, generic functions can be specialized depending upon any of their arguments. In this example, we’re defining forms of collide to work with a meteors and fighters:

(defmethod collide ((object-1 meteor) (object-2 fighter))

(format t "meteor ~a collides with fighter ~a" object-1 object-2))

(defmethod collide ((object-1 meteor) (object-2 meteor))

(format t "meteor ~a collides with another meteor ~a" object-1 object-2))

Common Lisp’s generic functions use dynamic dispatch on both object-1 and object-2 to determine which body of collide to evaluate. Meaning, both types are checked at run time, at the time when the function is invoked. Since more than one argument is checked dynamically, we say that Common Lisp has multiple dispatch.

Manifestly typed OO languages like Java appear to support multiple dispatch. You can create one method with several signatures, something like this:

interface Collidable {

public void crashInto(Meteor meteor);

public void crashInto(Fighter fighter);

}

class Meteor implements Collidable {

public void crashInto(Meteor meteor);

public void crashInto(Fighter fighter);

}

class Fighter implements Collidable {

public void crashInto(Meteor meteor);

public void crashInto(Fighter fighter);

}

Alas this won’t work. Although we can specialize crashInto by the type of its argument, the Java compiler resolves this specialization at compile time, not run time. It’s early bound. Thus, if we write something like this pseudo-Java:

Collidable thingOne = Math.random() < 0.5 ? new Meteor() : new Fighter(),

Collidable thingTwo = Math.random() < 0.5 ? new Meteor() : new Fighter();

thingOne.crashInto(thingTwo);

It won’t even compile! The compiler can figure out that thingOne is a Collidable and that it has two different signatures for the crashInto method, but all it knows about thingTwo is that it’s a Collidable, the compiler doesn’t know if it should be compiling an invocation of crashInto(Meteor meteor) or crashInto(Fighter fighter), so it refuses to compile this code.

Java’s system uses dynamic dispatch for the receiver of a method: The class of the receiver is determined at run time and the appropriate method is determined based on that class. But it uses static dispatch for the specialization based on arguments: The compiler sorts out which specialization to invoke based on the declared type of the argument at compile time. If it can’t sort that out, the code does not compile.

Java may have type signatures to specialize methods, but it is still single dispatch, just like JavaScript.

emulating multiple dispatch

Javascript cannot do true multiple dispatch without some ridiculous Greenspunning of method invocations. But we can fake it pretty reasonably using the same technique we used for emulating predicate dispatch.

We start with the same convention: Methods and functions must return something if they successfully hand a method invocation, or raise an exception if they catastrophically fail. They cannot return undefined (which in JavaScript, also includes not explicitly returning something).

Recall that this allowed us to write the Match function that took a serious of guards, functions that checked to see if the value of arguments was correct for each case. Our general-purpose guard, when, took all of the arguments as parameters.

function nameAndLength(name, length, body) {

var abcs = [ 'q', 'w', 'e', 'r', 't', 'y', 'u', 'i', 'o', 'p',

'a', 's', 'd', 'f', 'g', 'h', 'j', 'k', 'l',

'z', 'x', 'c', 'v', 'b', 'n', 'm' ],

pars = abcs.slice(0, length),

src = "(function " + name + " (" + pars.join(',') + ") { return body.appl\

y(this, arguments); })";

return eval(src);

}

function imitate(exemplar, body) {

return nameAndLength(exemplar.name, exemplar.length, body);

}

function getWith (prop, obj) {

function gets (obj) {

return obj[prop];

}

return obj === undefined

? gets

: gets(obj);

}

function mapWith (fn, mappable) {

function maps (collection) {

return collection.map(fn);

}

return mappable === undefined

? maps

: maps(collection);

}

function pluckWith (prop, collection) {

var plucker = mapWith(getWith(prop));

return collection === undefined

? plucker

: plucker(collection);

}

function Match () {

var fns = [].slice.call(arguments, 0),

lengths = pluckWith('length', fns),

length = Math.min.apply(null, lengths),

names = pluckWith('name', fns).filter(function (name) { return name !== \

''; }),

name = names.length === 0

? ''

: names[0];

return nameAndLength(name, length, function () {

var i,

value;

for (i in fns) {

value = fns[i].apply(this, arguments);

if (value !== undefined) return value;

}

});

}

What we want is to write guards for each argument. So we’ll write whenArgsAre, a guard that takes predicates for each argument as well as the body of the function case:

function isType (type) {

return function (arg) {

return typeof(arg) === type;

};

}

function instanceOf (clazz) {

return function (arg) {

return arg instanceof clazz;

};

}

function isPrototypeOf (proto) {

return Object.prototype.isPrototypeOf.bind(proto);

}

function whenArgsAre () {

var matchers = [].slice.call(arguments, 0, arguments.length - 1),

body = arguments[arguments.length - 1];

function typeChecked () {

var i,

arg,

value;

if (arguments.length != matchers.length) return;

for (i in arguments) {

arg = arguments[i];

if (!matchers[i].call(this, arg)) return;

}

value = body.apply(this, arguments);

return value === undefined

? null

: value;

}

return imitate(body, typeChecked);

}

function Fighter () {};

function Meteor () {};

var handlesManyCases = Match(

whenArgsAre(

instanceOf(Fighter), instanceOf(Meteor),

function (fighter, meteor) {

return "a fighter has hit a meteor";

}

),

whenArgsAre(

instanceOf(Fighter), instanceOf(Fighter),

function (fighter, fighter) {

return "a fighter has hit another fighter";

}

),

whenArgsAre(

instanceOf(Meteor), instanceOf(Fighter),

function (meteor, fighters) {

return "a meteor has hit a fighter";

}

),

whenArgsAre(

instanceOf(Meteor), instanceOf(Meteor),

function (meteor, meteor) {

return "a meteor has hit another meteor";

}

)

);

handlesManyCases(new Meteor(), new Meteor());

//=> 'a meteor has hit another meteor'

handlesManyCases(new Fighter(), new Meteor());

//=> 'a fighter has hit a meteor'

Our MultipleDispatch function now allows us to build generic functions that dynamically dispatch on all of their arguments. They work just fine for creating multiply dispatched methods:

var FighterPrototype = {},

MeteorPrototype = {};

FighterPrototype.crashInto = Match(

whenArgsAre(

isPrototypeOf(FighterPrototype),

function (fighter) {

return "fighter(fighter)";

}

),

whenArgsAre(

isPrototypeOf(MeteorPrototype),

function (fighter) {

return "fighter(meteor)";

}

)

);

MeteorPrototype.crashInto = Match(

whenArgsAre(

isPrototypeOf(FighterPrototype),

function (fighter) {

return "meteor(fighter)";

}

),

whenArgsAre(

isPrototypeOf(MeteorPrototype),

function (meteor) {

return "meteor(meteor)";

}

)

);

var someFighter = Object.create(FighterPrototype),

someMeteor = Object.create(MeteorPrototype);

someFighter.crashInto(someMeteor);

//=> 'fighter(meteor)'

We now have usable dynamic multiple dispatch for generic functions and for methods. It’s built on predicate dispatch, so it can be extended to handle other forms of guarding.

the opacity of functional composition

Consider the following problem:

We wish to create a specialized entity, an ArmoredFighter that behaves just like a regular fighter, only when it strikes another fighter it has some special behaviour.

var ArmoredFighterPrototype = Object.create(FighterPrototype);

ArmoredFighterPrototype.crashInto = Match(

whenArgsAre(

isPrototypeOf(FighterPrototype),

function (fighter) {

return "armored-fighter(fighter)";

}

)

);

Our thought is that we are “overriding” the behaviour of crashInto when an armored fighter crashes into any other kind of fighter. But we wish to retain the behaviour we have already designed when an armored fighter crashes into a meteor.

This is not going to work. Although we have written our code such that the various cases and predicates are laid out separately, at run time they are composed opaquely into functions. As far as JavaScript is concerned, we’ve written:

var FighterPrototype = {};

FighterPrototype.crashInto = function (q) {

// black box

};

var ArmoredFighterPrototype = Object.create(FighterPrototype);

ArmoredFighterPrototype.crashInto = function (q) {

// black box

};

We’ve written code that composes, but it doesn’t decompose. We’ve made it easy to manually take the code for these functions apart, inspect their contents, and put them back together in new ways, but it’s impossible for us to write code that inspects and decomposes the code.

A better design might incorporate reflection and decomposition at run time.