2. Why JPA and Hibernate matter

Although JDBC does a very good job of exposing a common API that hides the database vendor-specific communication protocol, it suffers from the following shortcomings:

- The API is undoubtedly verbose, even for trivial tasks.

- Batching is not transparent from the data access layer perspective, requiring a specific API than its non-batched statement counterpart.

- Lack of built-in support for explicit locking and optimistic concurrency control.

- For local transactions, the data access is tangled with transaction management semantics.

- Fetching joined relations requires additional processing to transform the

ResultSetinto Domain Models or DTO (Data Transfer Object) graphs.

Although the primary goal of an ORM (Object-Relational Mapping) tool is to automatically translate object state transitions into SQL statements, this chapter aims to demonstrate that Hibernate can address all the aforementioned JDBC shortcomings.

2.1 The impedance mismatch

When a relational database is manipulated through an object-oriented program, the two different data representations start conflicting.

In a relational database, data is stored in tables, and the relational algebra defines how data associations are formed. On the other hand, an object-oriented programming (OOP) language allows objects to have both state and behavior, and bidirectional associations are permitted.

The burden of converging these two distinct approaches has generated much tension, and it has been haunting enterprise systems for a very long time.

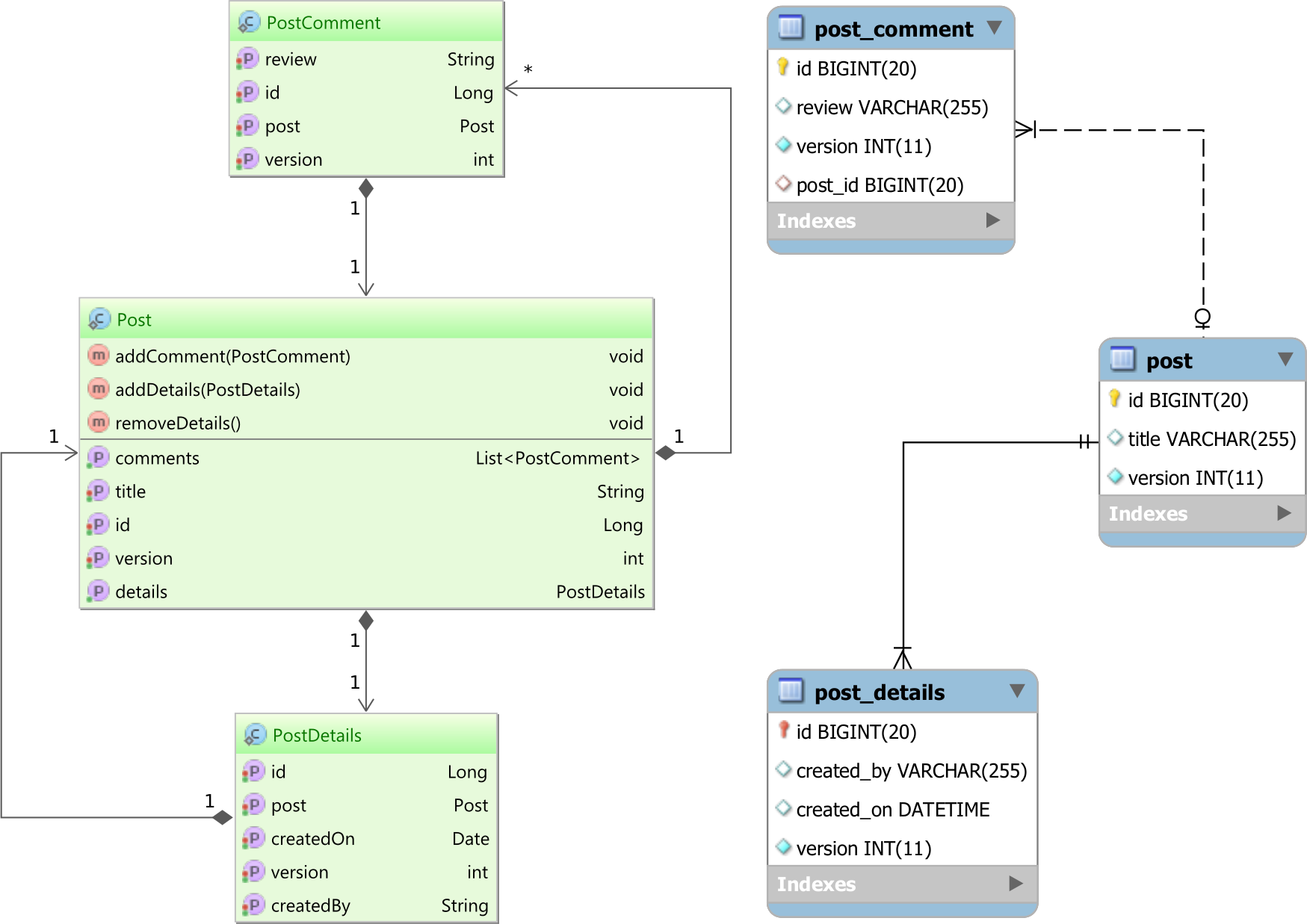

The above diagram portrays the two different schemas that the data access layer needs to correlate. While the database schema is driven by the SQL standard specification, the Domain Model comes with an object-oriented schema representation as well.

The Domain Model encapsulates the business logic specifications and captures both data structures and the behavior that governs business requirements. OOP facilitates Domain Modeling, and many modern enterprise systems are implemented on top of an object-oriented programming language.

Because the underlying data resides in a relational database, the Domain Model must be adapted to the database schema and the SQL-driven communication protocol. The ORM design pattern helps to bridge these two different data representations and close the technological gap between them. Every database row is associated with a Domain Model object (Entity in JPA terminology), and so the ORM tool can translate the entity state transitions into DML statements.

From an application development point of view, this is very convenient since it is much easier to manipulate Domain Model relationships rather than visualizing the business logic through its underlying SQL statements.

2.2 JPA vs. Hibernate

JPA is only a specification. It describes the interfaces that the client operates with and the standard object-relational mapping metadata (Java annotations or XML descriptors). Beyond the API definition, JPA also explains (although not exhaustively) how these specifications are ought to be implemented by the JPA providers. JPA evolves with the Java EE platform itself (Java EE 6 featuring JPA 2.0 and Java EE 7 introducing JPA 2.1).

Hibernate was already a full-featured Java ORM implementation by the time the JPA specification was released for the first time. Although it implements the JPA specification, Hibernate retains its native API for both backward compatibility and to accommodate non-standard features.

Even if it is best to adhere to the JPA standard, in reality, many JPA providers offer additional features targeting a high-performance data access layer requirements. For this purpose, Hibernate comes with the following non-JPA compliant features:

- extended identifier generators (hi/lo, pooled, pooled-lo)

- transparent prepared statement batching

- customizable CRUD (

@SQLInsert,@SQLUpdate,@SQLDelete) statements - static/dynamic entity/collection filters (e.g.

@FilterDef,@Filter,@Where) - mapping attributes to SQL fragments (e.g.

@Formula) - immutable entities (e.g.

@Immutable) - more flush modes (e.g.

FlushMode.MANUAL,FlushMode.ALWAYS) - querying the second-level cache by the natural key of a given entity

- entity-level cache concurrency strategies

(e.g.Cache(usage = CacheConcurrencyStrategy.READ_WRITE)) - versioned bulk updates through HQL

- exclude fields from optimistic locking check (e.g.

@OptimisticLock(excluded = true)) - versionless optimistic locking (e.g.

OptimisticLockType.ALL,OptimisticLockType.DIRTY) - support for skipping (without waiting) pessimistic lock requests

- support for Java 8 Date and Time and

stream() - support for multitenancy

The JPA implementation details leak and ignoring them might hinder application performance or even lead to data inconsistency issues. As an example, the following JPA attributes have a peculiar behavior, which can surprise someone who is familiar with the JPA specification only:

- The FlushModeType.AUTO does not trigger a flush for native SQL queries like it does for JPQL or Criteria API.

- The FetchType.EAGER might choose a SQL join or a secondary select whether the entity is fetched directly from the

EntityManageror through a JPQL (Java Persistence Query Language) or a Criteria API query.

That is why this book is focused on how Hibernate manages to implement both the JPA specification and its non-standard native features (that are relevant from an efficiency perspective).

Portability concerns

Like other non-functional requirements, portability is a feature, and there is still a widespread fear of embracing database-specific or framework-specific features. In reality, it is more common to encounter enterprise applications facing data access performance issues than having to migrate from one technology to the other (be it a relational database or a JPA provider).

The lowest common denominator of many RDBMS is a superset of the SQL-92 standard (although not entirely supported either).

SQL-99 supports Common Table Expressions, but MySQL 5.7 does not. Although SQL-2003 defines the MERGE operator, PostgreSQL 9.5 favored the UPSERT operation instead.

By adhering to a SQL-92 syntax, one could achieve a higher degree of database portability, but the price of giving up database-specific features can take a toll on application performance.

Portability can be addressed either by subtracting non-common features or through specialization.

By offering different implementations, for each supported database system (like the jOOQ framework does), portability can still be achieved.

The same argument is valid for JPA providers too. By layering the application, it is already much easier to swap JPA providers, if there is even a compelling reason for switching one mature JPA implementation with another.

2.3 Schema ownership

Because of data representation duality, there has been a rivalry between taking ownership of the underlying schema. Although theoretically, both the database and the Domain Model could drive the schema evolution, for practical reasons, the schema belongs to the database.

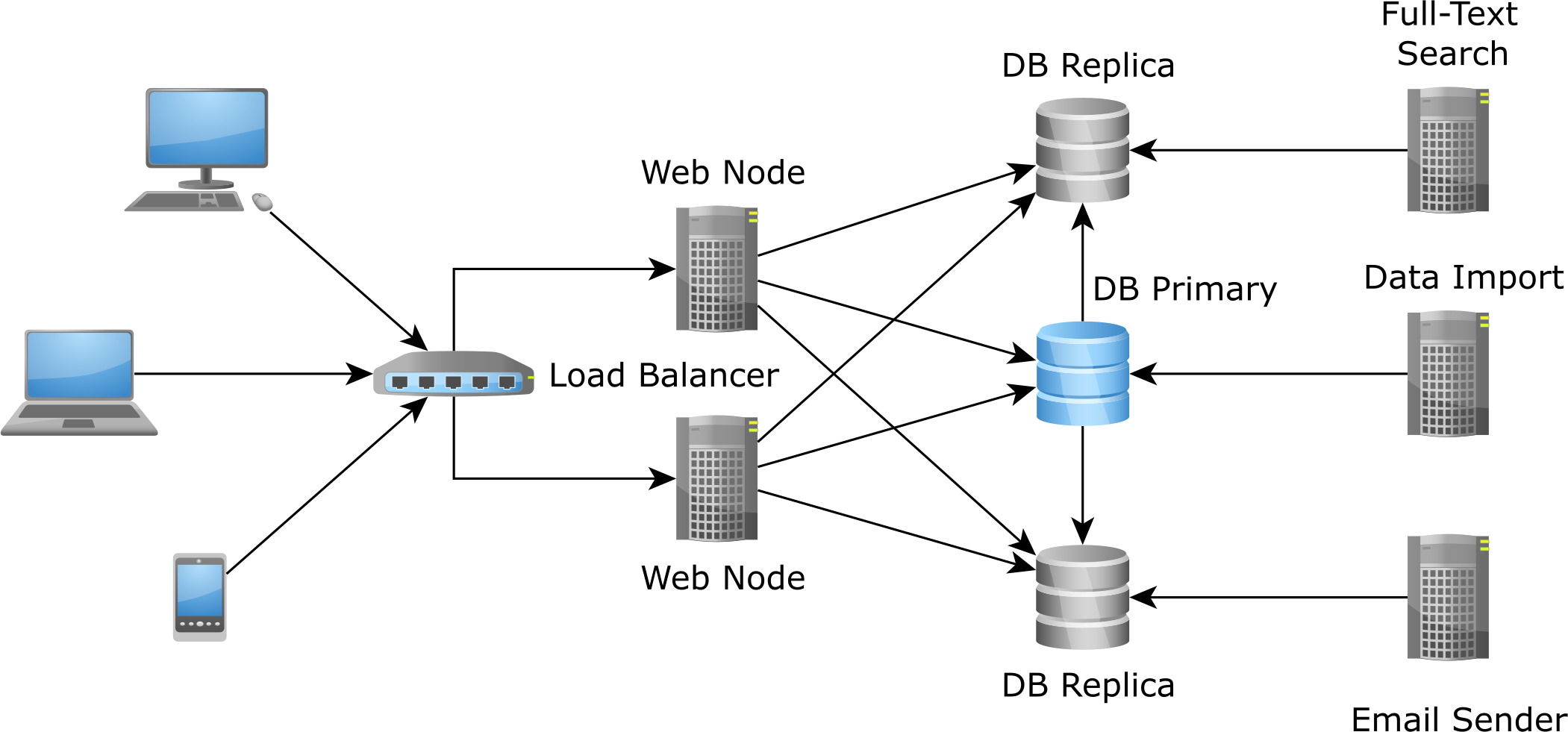

An enterprise system might be too large to fit into a single application, so it is not uncommon to split in into multiple subsystems, each one serving a specific goal. As an example, there can be front-end web applications, integration web services, email schedulers, full-text search engines and back-end batch processors that need to load data into the system. All these subsystems need to use the underlying database, whether it is for displaying content to the users or dumping data into the system.

Although it might not fit any enterprise system, having the database as a central integration point can still be a choice for many reasonable size enterprise systems.

The relational database concurrency models offer strong consistency guarantees, therefore having a significant advantage to application development. If the integration point does not provide transactional semantics, it will be much more difficult to implement a distributed concurrency control mechanism.

Most database systems already offer support for various replication topologies, which can provide more capacity for accommodating an increase in the incoming request traffic. Even if the demand for more data continues to grow, the hardware is always getting better and better (and cheaper too), and database vendors keep on improving their engines to cope with more data.

For these reasons, having the database as an integration point is still a relevant enterprise system design consideration.

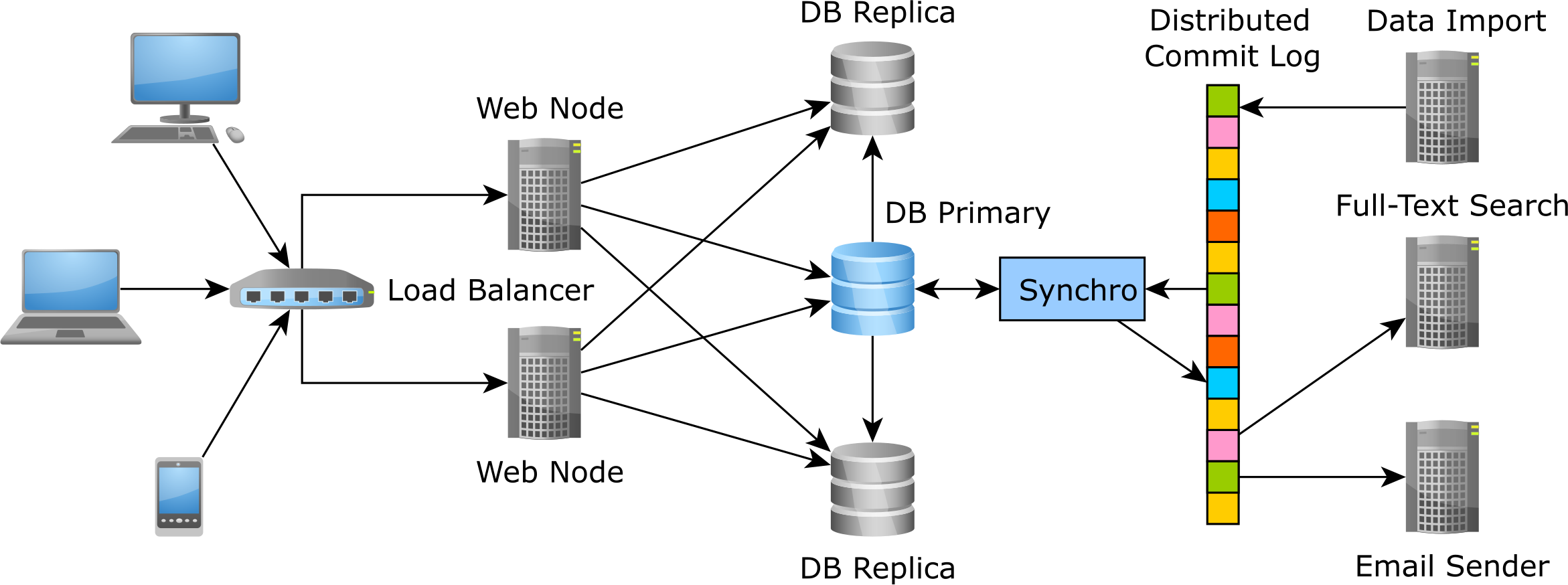

The distributed commit log

For very large enterprise systems, where data is split among different providers (relational database systems, caches, Hadoop, Spark), it is no longer possible to rely on the relational database to integrate all disparate subsystems.

In this case, Apache Kafka offers a fault-tolerant and scalable append-only log structure, which every participating subsystem can read and write concurrently.

The commit log becomes the integration point, each distributed node individually traversing it and maintaining client-specific pointers in the sequential log structure. This design resembles a database replication mechanism, and so it offers durability (the log is persisted on disk), write performance (append-only logs do not require random access) and read performance (concurrent reads do not require blocking) as well.

No matter what architecture style is chosen, there is still need to correlate the transient Domain Model with the underlying persistent data.

The data schema evolves along the enterprise system itself, and so the two different schema representations must remain congruent at all times.

Even if the data access framework can auto-generate the database schema, the schema must be migrated incrementally, and all changes need to be traceable in the VCS (Version Control System) as well. Along with table structure, indexes and triggers, the database schema is, therefore, accompanying the Domain Model source code itself. A tool like Flywaydb can automate the database schema migration, and the system can be deployed continuously, whether it is a test or a production environment.

The schema ownership goes to the database, and the data access layer must assist the Domain Model to communicate with the underlying data.

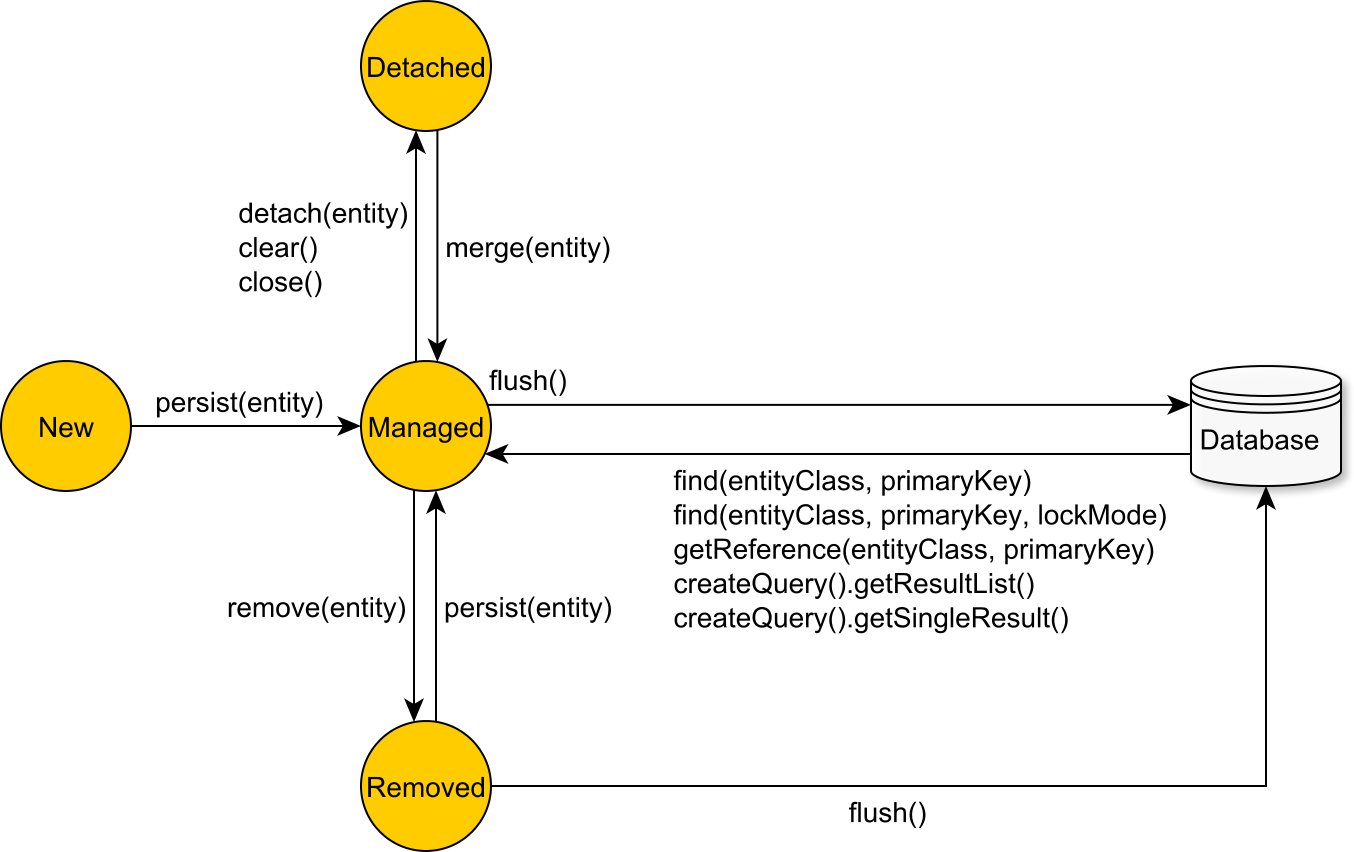

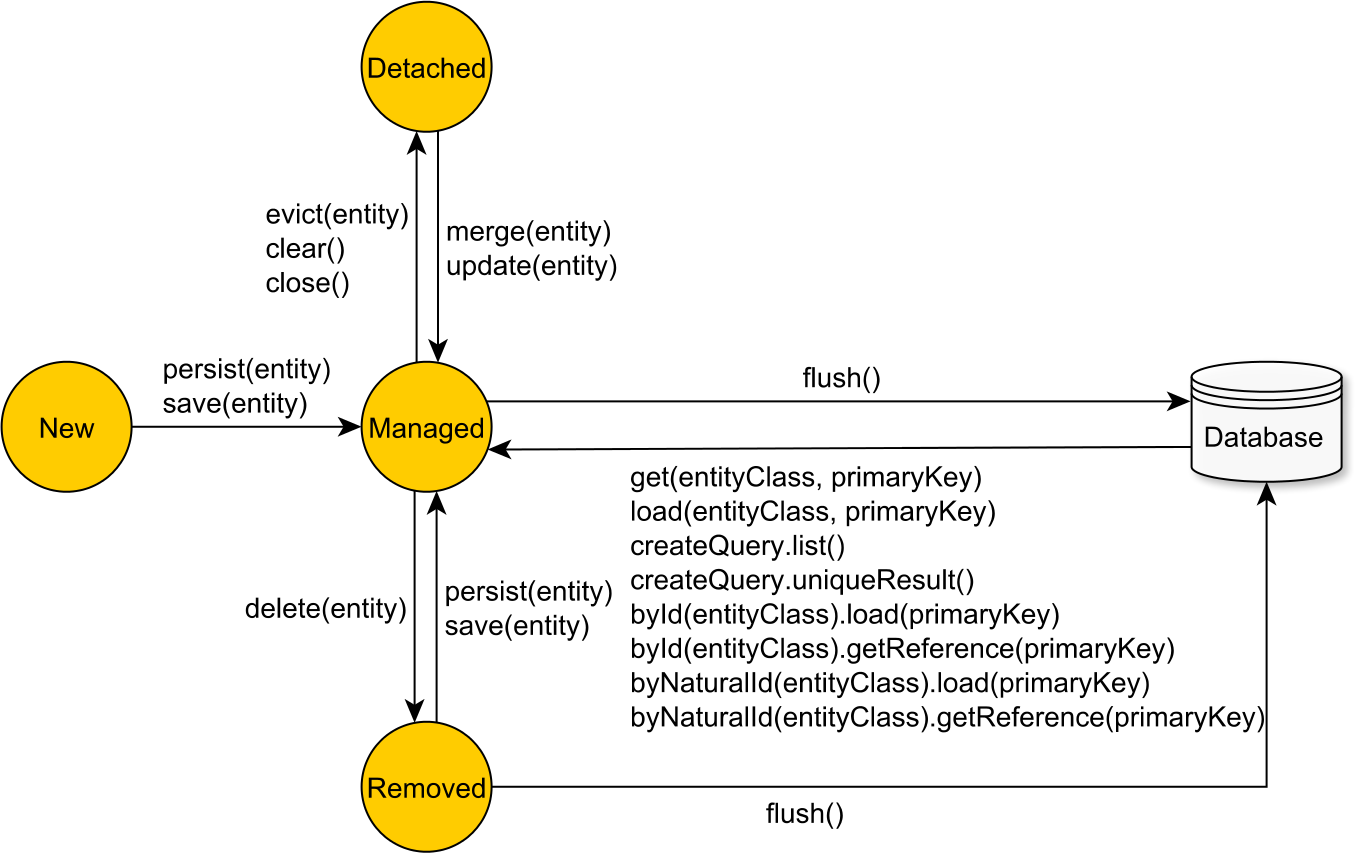

2.4 Entity state transitions

JPA shifts the developer mindset from SQL statements to entity state transitions. An entity can be in one of the following states:

| State | Description |

|---|---|

| New (Transient) | A newly created entity which is not mapped to any database row is considered to be in the New or Transient state. Once it becomes managed, the Persistence Context issues an insert statement at flush time. |

| Managed (Persistent) | A Persistent entity is associated with a database row, and it is being managed by the currently running Persistence Context. State changes are detected by the dirty checking mechanism and propagated to the database as update statements at flush time. |

| Detached | Once the currently running Persistence Context is closed, all the previously managed entities become detached. Successive changes are no longer tracked, and no automatic database synchronization is going to happen. |

| Removed | A removed entity is only scheduled for deletion, and the actual database delete statement is executed during Persistence Context flushing. |

The Persistence Context captures entity state changes, and, during flushing, it translates them into SQL statements.

The JPA EntityManager and the Hibernate Session (which includes additional methods for moving an entity from one state to the other) interfaces are gateways towards the underlying Persistence Context,

and they define all the entity state transition operations.

2.5 Write-based optimizations

SQL injection prevention

By managing the SQL statement generation, the JPA tool can assist in minimizing the risk of SQL injection attacks.

The less the chance of manipulating SQL String statements, the safer the application can get. The risk is not completely eliminated because the application developer can still recur to concatenating SQL or JPQL fragments, so rigor is advised.

Hibernate uses PreparedStatement(s) exclusively, so not only it protects against SQL injection, but the data access layer can better take advantage of server-side and client-side statement caching as well.

Auto-generated DML statements

The enterprise system database schema evolves with time, and the data access layer must mirror all these modifications as well.

Because the JPA provider auto-generates insert and update statements, the data access layer can easily accommodate database table structure modifications. By updating the entity model schema, Hibernate can automatically adjust the modifying statements accordingly.

This applies to changing database column types as well.

If the database schema needs to migrate a postal code from an INT database type to a VARCHAR(6),

the data access layer will need only to change the associated Domain Model attribute type from an Integer to a String, and all statements are going to be automatically updated.

Hibernate defines a highly customizable JDBC-to-database type mapping system, and the application developer can override a default type association, or even add support for new database types (that are not currently supported by Hibernate).

The entity fetching process is automatically managed by the JPA implementation, which auto-generates the select statements of the associated database tables. This way, JPA can free the application developer from maintaining entity selection queries as well.

Hibernate allows customizing all the CRUD statements, in which case the application developer is responsible for maintaining the associated DML statements.

Although it takes care of the entity selection process, most enterprise systems need to take advantage of the underlying database querying capabilities. For this reason, whenever the database schema changes, all the native SQL queries need to be updated manually (according to their associated business logic requirements).

Write-behind cache

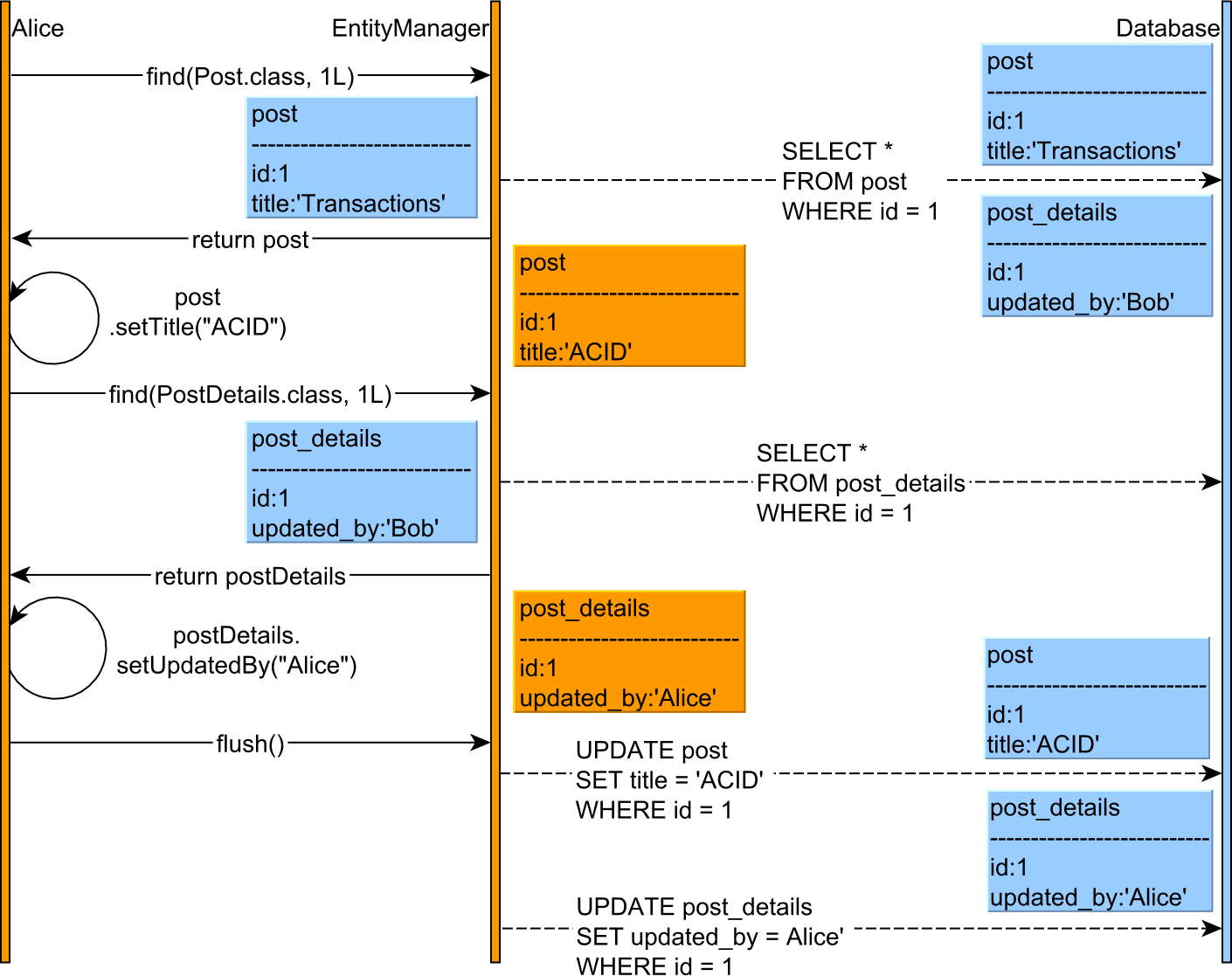

The Persistence Context acts as a transactional write-behind cache, deferring entity state flushing up until the last possible moment.

Because every modifying DML statement requires locking (to prevent dirty writes), the write behind cache can reduce the database lock acquisition interval, therefore increasing concurrency.

However, caches introduce consistency challenges, and the Persistence Context requires a flush prior to executing any JPQL or native SQL query, as otherwise it might break the read-your-own-write consistency guarantee.

As detailed in the following chapters, Hibernate does not automatically flush pending changes when a native query is about to be executed, and the application developer must explicitly instruct what database tables are needed to be synchronized.

Transparent statement batching

Since all changes are being flushed at once, Hibernate may benefit from batching JDBC statements. Batch updates can be enabled transparently, even after the data access logic has been implemented. Most often, performance tuning is postponed until the system is already running in production, and switching to batching statements should not require a considerable development effort.

With just one configuration, Hibernate can execute all prepared statements in batches.

Application-level concurrency control

As previously explained, no database isolation level can protect against losing updates when executing a multi-request long conversation. JPA supports both optimistic and pessimistic locking.

The JPA optimistic locking mechanism allows preventing lost updates because it imposes a happens-before event ordering. However, in multi-request conversations, optimistic locking requires maintaining old entity snapshots, and JPA makes it possible through Extended Persistence Contexts or detached entities.

A Java EE application server can preserve a given Persistence Context across several web requests, therefore providing application-level repeatable reads. However, this strategy is not free since the application developer must make sure the Persistence Context is not bloated with too many entities, which, apart from consuming memory, it can also affect the performance of the Hibernate default dirty checking mechanism.

Even when not using Java EE, the same goal can be achieved using detached entities, which provide fine-grained control over the amount of data needed to be preserved from one web request to the other. JPA allows merging detached entities, which rebecome managed and automatically synchronized with the underlying database system.

JPA also supports a pessimistic locking query abstraction, which comes in handy when using lower-level transaction isolation modes.

Hibernate has a native pessimistic locking API, which brings support for timing out lock acquisition requests or skipping already acquired locks.

2.6 Read-based optimizations

Following the SQL standard, the JDBC ResultSet is a tabular representation of the underlying fetched data.

The Domain Model being constructed as an entity graph, the data access layer must transform the flat ResultSet into a hierarchical structure.

Although the goal of the ORM tool is to reduce the gap between the object-oriented Domain Model and its relational counterpart, it is very important to remember that the source of data is not an in-memory repository, and the fetching behavior influences the overall data access efficiency.

The database cannot be abstracted out of this context, and pretending that entities can be manipulated just like any other plain objects is very detrimental to application performance. When it comes to reading data, the impedance mismatch becomes even more apparent, and, for performance reasons, it is mandatory to keep in mind the SQL statements associated with every fetching operation.

In the following example, the posts records are fetched along with all their associated comments. Using JDBC, this task can be accomplished using the following code snippet:

doInJDBC(connection -> {

try (PreparedStatement statement = connection.prepareStatement(

"SELECT * " +

"FROM post AS p " +

"JOIN post_comment AS pc ON p.id = pc.post_id " +

"WHERE " +

" p.id BETWEEN ? AND ? + 1"

)) {

statement.setInt(1, id);

statement.setInt(2, id);

try (ResultSet resultSet = statement.executeQuery()) {

List<Post> posts = toPosts(resultSet);

assertEquals(expectedCount, posts.size());

}

} catch (SQLException e) {

throw new DataAccessException(e);

}

});

When joining many-to-one or one-to-one associations, each ResultSet record corresponds to a pair of entities, so both the parent and the child can be resolved in each iteration.

For one-to-many or many-to-many relationships, because of how the SQL join works, the ResultSet contains a duplicated parent record for each associated child.

Constructing the hierarchical entity structure requires manual ResultSet transformation, and, to resolve duplicates, the parent entity references are stored in a Map structure.

List<Post> toPosts(ResultSet resultSet) throws SQLException {

Map<Long, Post> postMap = new LinkedHashMap<>();

while (resultSet.next()) {

Long postId = resultSet.getLong(1);

Post post = postMap.get(postId);

if(post == null) {

post = new Post(postId);

postMap.put(postId, post);

post.setTitle(resultSet.getString(2));

post.setVersion(resultSet.getInt(3));

}

PostComment comment = new PostComment();

comment.setId(resultSet.getLong(4));

comment.setReview(resultSet.getString(5));

comment.setVersion(resultSet.getInt(6));

post.addComment(comment);

}

return new ArrayList<>(postMap.values());

}

The JDBC 4.2 PreparedStatement supports only positional parameters, and the first ordinal starts from 1.

JPA allows named parameters as well, which are especially useful when a parameter needs to be referenced multiple times, so the previous example can be rewritten as follows:

doInJPA(entityManager -> {

List<Post> posts = entityManager.createQuery(

"select distinct p " +

"from Post p " +

"join fetch p.comments " +

"where " +

" p.id BETWEEN :id AND :id + 1", Post.class)

.setParameter("id", id)

.getResultList();

assertEquals(expectedCount, posts.size());

});

In both examples, the object-relation transformation takes place either implicitly or explicitly. In the JDBC use case, the associations must be manually resolved, while JPA does it automatically (based on the entity schema).

The fetching responsibility

Besides mapping database columns to entity attributes, the entity associations can also be represented in terms of object relationships. More, the fetching behavior can be hard-wired to the entity schema itself, which is most often a terrible thing to do.

Fetching multiple one-to-many or many-to-many associations is even more problematic because they might require a Cartesian Product, therefore affecting performance. Controlling the hard-wired schema fetching policy is cumbersome as it prevents overriding an eager retrieval with a lazy loading mechanism.

Each business use case has different data access requirements, and one policy cannot anticipate all possible use cases, so the fetching strategy should always be set up on a query basis.

Prefer projections for read-only views

Although it is very convenient to fetch entities along with all their associated relationships, it is better to take into consideration the performance impact as well. As previously explained, fetching too much data is not suitable because it increases the transaction response time.

In reality, not all use cases require loading entities, and not all read operations need to be served by the same fetching mechanism. Sometimes a custom projection (selecting only a few columns from an entity) is much more suitable, and the data access logic can even take advantage of database-specific SQL constructs that might not be supported by the JPA query abstraction.

As a rule of thumb, fetching entities is suitable when the logical transaction requires modifying them, even if that only happens in a successive web request. With this in mind, it is much easier to reason on which fetching mechanism to employ for a given business logic use case.

The second-level cache

If the Persistence Context acts as a transactional write-behind cache, its lifetime will be bound to that of a logical transaction. For this reason, the Persistence Context is also known as the first-level cache, and so it cannot be shared by multiple concurrent transactions.

On the other hand, the second-level cache is associated with an EntityManagerFactory, and all Persistence Contexts have access to it.

The second-level cache can store entities as well as entity associations (one-to-many and many-to-many relationships) and even entity query results.

Because JPA does not make it mandatory, each provider takes a different approach to caching (as opposed to EclipseLink, by default, Hibernate disables the second-level cache).

Most often, caching is a trade-off between consistency and performance. Because the cache becomes another source of truth, inconsistencies might occur, and they can be prevented only when all database modifications happen through a single EntityManagerFactory or a synchronized distributed caching solution.

In reality, this is not practical since the application might be clustered on multiple nodes (each one with its own EntityManagerFactory) and the database might be accessed by multiple applications.

Although the second-level cache can mitigate the entity fetching performance issues, it requires a distributed caching implementation, which might not elude the networking penalties anyway.

2.7 Wrap-up

Bridging two highly-specific technologies is always a difficult problem to solve. When the enterprise system is built on top of an object-oriented language, the object-relational impedance mismatch becomes inevitable. The ORM pattern aims to close this gap although it cannot completely abstract it out.

In the end, all the communication flows through JDBC and every execution happens in the database engine itself. A high-performance enterprise application must resonate with the underlying database system, and the ORM tool must not disrupt this relationship.

Just like the problem it tries to solve, Hibernate is a very complex framework with many subtleties that require a thorough knowledge of both database systems, JDBC, and the framework itself. This chapter is only a summary, meant to present JPA and Hibernate into a different perspective that prepares the reader for high-performance object-relational mapping. There is no need to worry if some topics are not entirely clear because the upcoming chapters analyze all these concepts in greater detail.